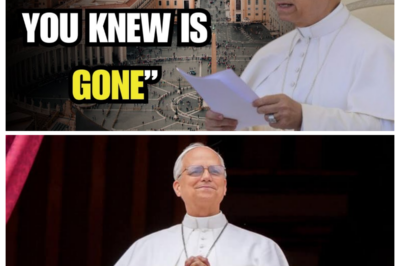

This 1899 family portrait was restored, and a secret was only revealed now

This 1899 family portrait was restored, and a secret was only revealed now.

The afternoon light filtered through the tall windows of Morgan’s restoration studio in Philadelphia, casting long shadows across her workbench.

She adjusted her magnifying lamp and studied the photograph that had arrived that morning, a family portrait from 1899, mounted in a cracked leather frame.

The image was barely visible, obscured by water damage, age spots, and a deep crease that ran diagonally across the lower portion.

The client’s email had been brief.

found this in my grandmother’s attic.

Family portrait.

Would love to see it restored before I pass it down to my daughter.

Morgan had been restoring historical photographs for 12 years, and she’d seen countless portraits from the turn of the century.

This one appeared straightforward at first glance.

Four figures posed in the stiff, formal manner typical of the era.

A man and woman stood in the back, their faces stern and dignified.

Two younger people, likely their adult children, flanked them on either side.

She carefully removed the photograph from its frame, noting the brittle edges and the foxing that had eaten away at portions of the emulsion.

The studio mark on the back was partially legible.

Richardson’s photography, Philadelphia, PA, 1899.

Setting up her scanner, Morgan began the meticulous process of digitization.

She worked at the highest resolution possible, knowing that every pixel might contain information invisible to the naked eye.

As the scan completed, she transferred the file to her main monitor and opened it in a restoration software.

The first step was always the same.

Assess the damage, mapped the areas that needed attention, and create a restoration plan.

She zoomed in slowly, examining each section of the photograph.

The faces were weathered but recoverable.

The background, likely a painted studio backdrop depicting a Victorian parlor, was faded but intact.

Then her eye caught something in the damaged area at the bottom of the frame, where the crease had obliterated most of the detail.

She leaned closer to the screen.

There was a shape there, something she’d initially dismissed as shadow or damage.

But as she adjusted the contrast slightly, the shape seemed to have form, structure.

Morgan’s pulse quickened.

In all her years of restoration work, she learned to trust these moments when something felt off when an image whispered that it held more than met the eye.

She saved her work and stood up, stretching.

Tomorrow, she would begin the careful process of rebuilding that damaged section pixel by pixel.

She had no idea that she was about to uncover a secret that had been hidden for 125 years.

Morgan arrived at her studio early the next morning, coffee in hand and determination in her stride.

The 1899 portrait waited on her screen exactly as she’d left it.

The mysterious shape in the damaged section still nagging at her mind.

She dreamed about it.

Fragmented images of shadows that became solid, secrets hiding in plain sight.

She settled into her chair and began the painstaking work of digital restoration.

Using advanced algorithms and her own trained eye, she started reconstructing the damaged area pixel by pixel.

The software analyzed surrounding patterns, suggesting probable continuations of lines and textures.

But Morgan always made the final decisions, guided by years of experience and an almost intuitive understanding of photographic composition.

After two hours of concentrated work, she leaned back and blinked hard.

The shape was definitely not damage.

It was a form rounded at the top, narrowing downward.

She increased the magnification and continued working, carefully removing the digital artifacts of water damage and age.

By noon, she could no longer deny what she was seeing.

It was a head, a small head positioned low in the frame, as if someone were sitting on the floor or very low stool, a child.

Morgan’s heart raced.

She pulled up the client’s email again, reading it carefully.

Four people.

The family records mentioned four people, but here emerging from more than a century of obscurity, was clearly a fifth figure.

She worked through lunch, her sandwich forgotten on the desk beside her.

As she reconstructed more of the image, details emerged.

Small shoulders, the suggestion of a simple dress, tiny hands folded in a lap.

The child appeared to be perhaps four or 5 years old, positioned slightly forward and to the left of the woman she now assumed was the family matriarch.

The placement was unusual.

In typical Victorian family portraits, children were positioned prominently.

They were, after all, symbols of legacy and continuity.

But this child seemed almost tucked away, present, but not centered, visible, but not emphasized.

By late afternoon, Morgan had restored enough of the child’s figure to see the face beginning to emerge.

She adjusted the contrast and brightness carefully, teasing out details from the degraded emulsion.

The eyes were downcast, the expression solemn, typical for photographs of that era when subjects had to remain perfectly still for long exposures.

Then she enhanced the lighting in that specific area, a standard technique to recover detail from underexposed sections.

The screen flickered as the algorithm processed the adjustment.

Morgan froze.

The child’s skin tone, now clearly visible in the restored image, was distinctly lighter than the four adults surrounding her, significantly lighter.

She sat back in her chair, her mind racing through the implications.

a black family in 1899 Philadelphia and a white child sitting among them photographed as if she belonged there.

This wasn’t just a restoration project anymore.

This was a mystery.

Morgan spent the rest of the day completing the basic restoration of the photograph, but her mind was elsewhere, circling around the questions that the fifth figure had raised.

By evening, she had a clear, detailed image of all five people.

The family stood with quiet dignity.

The parents in their Sunday best, their expressions serious and proud.

The two younger adults, likely in their 20s, wore similar expressions of formal composure, and there at the front sat the small white child, her blonde hair pulled back, her pale hands folded primly in her lap.

Morgan saved multiple versions of the file, and then did something she rarely did before completing a full restoration.

She called the client.

“Mrs.

Patterson, this is Morgan Chen from the restoration studio.

I hope I’m not calling too late.

” “Not at all, dear,” came the warm voice on the other end.

“Have you had a chance to look at the photograph? I have and I’ve made significant progress.

But I need to ask you something.

The family in this portrait, what do you know about them? There was a pause.

Well, that’s my great great grandparents, Thomas and Ruth, and their children, Samuel and Grace.

Why do you ask? Morgan chose her words carefully.

Mrs.

Patterson, in the restoration process, I’ve discovered that there’s actually a fifth person in the photograph.

A young child, maybe four or 5 years old.

She was hidden by damage to the image, but I’ve been able to recover her.

Did you know there was another child in the family? The silence on the other end stretched long enough that Morgan wondered if the connection had dropped.

A fifth person? Mrs.

Patterson’s voice had changed, become quieter.

No, that’s I’ve never heard anyone mention another child.

Are you certain? Absolutely certain.

She’s sitting at the front of the group.

Mrs.

Patterson, there’s something else.

The child appears to be white.

Another long pause.

Then white, but that’s that doesn’t make any sense.

Thomas and Ruth were black.

Their whole family was black.

We have records, family Bible entries, everything.

There’s never been any mention of,” she trailed off.

“I understand this is unexpected,” Morgan said gently.

“But the image is clear.

I’m going to send you what I’ve restored so far.

Maybe you could look through your family documents.

See if there’s anything that might explain this.

” “Yes,” Mrs.

Patterson said, her voice distant now, thoughtful.

Yes, I’ll look.

My grandmother left boxes of letters and papers.

I never went through most of them.

Morgan, this is if what you’re saying is true, this could be important.

This could change what we know about our family.

After they hung up, Morgan sat in the dimming light of her studio, staring at the photograph on her screen.

Five faces looked back at her across the span of more than a century.

Four of them had been remembered, documented, passed down through family stories.

But one had been erased, hidden not just by photographic damage, but by something deeper, by silence, by time, by deliberate forgetting.

She zoomed in on the child’s face.

“Who were you?” she thought.

“And and why did they hide you?” 3 days later, Morgan’s phone rang at 9:00 in the morning.

“It was Mrs.

Patterson, and her voice carried an edge of excitement mixed with confusion.

” “I found something,” she said without preamble.

in my grandmother’s papers.

Letters Morgan letters from Ruth to her sister in New York dated from 1897 to 1902.

Morgan grabbed her notebook.

What do they say? Most of them are ordinary family news, church events, recipes, but there’s one from September 1899, just a few months after that photograph was taken.

Ruth writes, “The child is well and growing.

We have made our peace with the looks we receive at market.

Thomas says, “We do what is right before God, and that is enough.

Sarah has learned to say our names now, and her laughter fills the house.

” “Morgan, she’s talking about a child named Sarah, but there’s no Sarah in our family tree.

” Morgan felt the familiar thrill of discovery, the sense of a story beginning to reveal itself.

“Is there anything else? Any other mention of her?” “Yes, scattered through several letters over the next two years, always brief, always careful.

” In one letter from 1900, Ruth writes, “We have had visits from the church ladies asking questions we do not answer.

They do not understand, and we have decided it is not their place to understand.

” And then in early 1901, Sarah grows tall and asks questions about her mother.

We tell her what we know, which is little enough.

She is ours now in all the ways that matter.

Morgan scribbled notes rapidly.

Does she ever explain how Sarah came to be with them? Not directly, but there’s a letter from December 1896.

That’s three years before the photograph.

Ruth writes, “A terrible thing happened at the docks today.

A woman fell, and by the time Thomas reached her, she was gone.

She had a child with her, barely 2 years old, crying in the cold.

No one came forward to claim her.

Thomas brought them both to the church.

The woman had no papers, no name we could find.

The child had nothing but the clothes on her back.

” “Morgan, I think that’s how it started.

” Morgan set down her pen, imagining the scene.

A bustling Philadelphia dock in 1896.

A woman falling.

A child left alone in a crowd where no one wanted the responsibility of a white orphan.

And Thomas, Mrs.

Patterson’s great greatgrandfather stepping forward when others stepped back.

Mrs.

Patterson in 1896.

What would have happened if a black man brought a white child home? The older woman’s voice dropped.

Nothing good.

This was after reconstruction collapsed during the worst of Jim Crow.

Even in Philadelphia, which was better than the South, there were rules, unspoken rules.

A black family raising a white child.

People would have assumed the worst, that she’d been stolen, that something criminal was happening.

They could have been arrested, lost everything worse.

But they did it anyway.

They did it anyway, Mrs.

Patterson repeated softly.

And they never told anyone.

Morgan, there’s one more thing.

The letters stopped mentioning Sarah after 1902.

I’ve been through everything.

There’s nothing after that.

It’s like she just disappeared from the record.

Morgan looked at the photograph on her screen at the small figure sitting with the family.

Her presence captured but her story erased.

We need to find out what happened to her.

If she’s in this photograph sitting with them like family, then she mattered to them.

We owe it to Thomas and Ruth to finish their story.

How do we do that? Morgan smiled, though Mrs.

Patterson couldn’t see it.

We start digging.

church records, census data, newspaper archives.

She left traces.

Everyone does.

We just have to find them.

Morgan spent the next week immersed in the past.

She started with the 1900 census, searching for Thomas and Ruth’s household in Philadelphia’s seventh ward.

When she found the entry, her breath caught.

Thomas Parker, age 42, laborer.

Ruth Parker, age 38, laress.

Samuel Parker, age 21, porter.

Grace Parker, age 19, domestic worker.

and then written in a different hand squeezed into the margin as if added later.

Sarah, age five, white.

Someone had recorded her.

A census taker had seen her living in that black household and had noted it, but the entry had been pushed to the edge of the page, made peripheral, almost apologetic.

Morgan photographed the record and sent it to Mrs.

Patterson.

The trail led next to church records.

Morgan contacted the African Episcopal Church of St.

Thomas, the oldest black Episcopal church in Philadelphia.

The archivist, a patient man named Marcus, spent an afternoon pulling dusty ledgers from the archives.

Here, he said, pointing to an entry from 1897.

Ruth Parker, new member, transferred from Baltimore.

And look, there’s a note.

Has taken in an orphaned child, Sarah, age approximately three.

Child receives Christian instruction and attends Sunday services.

They brought her to church, Morgan said amazed.

They didn’t hide her.

Marcus nodded slowly.

The black church was different then.

It was refuge community.

If the Parker said this child needed a home, the congregation would have supported them, even knowing the risks.

But look at this.

He turned the page to 1899.

Sarah Parker, baptized, age 5.

Parents listed as Thomas and Ruth Parker.

Morgan stared at the entry.

They claimed her officially made her legally theirs in the eyes of the church.

It wouldn’t have meant anything in civil law.

Marcus cautioned.

Adoption laws in 1899, Pennsylvania wouldn’t have allowed a black couple to adopt a white child.

But in the church here, they were her parents.

That night, Morgan met Mrs.

Patterson at a small cafe near the studio.

“The older woman had brought a cardboard box filled with more family documents, photographs, newspaper clippings, a family Bible.

“I found something else,” Mrs.

Patterson said, opening the Bible to the family records page.

“Look at the births.

” Morgan scanned the handwritten entries.

“Samuel, born 1879.

Grace, born 1881, and then in different ink added later.

Sarah, born approximately 1894, came to us 1896.

Blessed be God who gives us this precious gift.

Ruth wrote that, Mrs.

Patterson said quietly.

My grandmother told me Ruth kept the family Bible meticulously.

Every birth, every death, every marriage.

Sarah is written there, Morgan.

She’s written there as family.

Morgan turned the pages carefully.

Marriages, deaths, births of grandchildren, all recorded in Ruth’s careful hand.

The last entry in Ruth’s handwriting was dated 1903.

Thomas gone to his rest, age 45.

Beloved husband and father.

Thomas died young, Morgan observed.

According to family stories, it was an accident at the docks.

He was helping unload cargo when something fell.

Killed instantly.

Mrs.

Patterson’s eyes were distant.

Ruth lived another 30 years after that, raised her children and grandchildren, but she never remarried.

Morgan turned back to Sarah’s entry.

Mrs.

Patterson, what happened to Sarah? The letter stop in 1902, and there’s no death recorded here in the Bible.

I don’t know, and that’s what frightens me.

The older woman’s hands trembled slightly as she closed the Bible.

In all the family stories my grandmother told me, and all the documents and photographs, there’s no mention of Sarah after that photograph.

It’s as if she simply vanished.

Morgan’s next stop was the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, where she requested access to the Philadelphia Newspaper Archives from 1900 to 1905.

If something had happened to Sarah, something significant enough to erase her from family memory, there might be a record.

She started with the Philadelphia Inquirer, scanning page after page of brittle microfilm, social announcements, crime reports, advertisements for miracle tonics and ladies corsets, the world of 1899.

Philadelphia emerged in fragments, a city of stark contrasts, where wealthy industrialists built mansions while immigrants and black families crowded into tenementss, where progress and prejudice walked hand in hand down cobblestone streets.

On her third day in the archives, she found it.

The article was small, buried on page 7 of the January 14th, 1902 edition under the headline, “Authorities investigate household irregularity.

” Morgan’s hands shook as she read, “Police were summoned to a residence on Lombard Street yesterday following complaints from neighbors regarding a white child living in the home of Thomas and Ruth Parker, both colored.

The child, identified as Sarah, approximately age 7, has reportedly resided with the family for several years.

Mrs.

Henrietta Worthington, a resident of the neighboring property, expressed concern for the child’s welfare and moral education.

It is simply not proper, Mrs.

Warthington stated, “The child should be with her own kind in a Christian home where she can be properly raised.

” The Parkers refused to comment when questioned by this reporter.

“The matter has been referred to the Philadelphia Society for Organizing Charity, which oversees the placement of dependent children.

” Morgan’s stomach turned.

She photographed the article and kept searching.

Two weeks later, another brief mention.

The Society for Organizing Charity has determined that the child Sarah, formerly residing with a colored family on Lombard Street, is to be removed to a suitable home.

Mrs.

Adelaide Crane, superintendent of the society, stated that while the colored family appears to have treated the child adequately, it is in the child’s best interest to be raised in a home with people of her own race and social station.

Morgan found Mrs.

Patterson’s number with trembling fingers.

They took her, Morgan said when the older woman answered.

In 1902, the authorities took Sarah away from Thomas and Ruth.

The silence, on the other end, was heavy with grief.

Because of their skin color, Mrs.

Patterson said finally.

It wasn’t a question.

Because a neighbor complained.

Because someone decided a white child couldn’t possibly belong with a black family, no matter how much they loved her.

Morgan’s voice cracked with anger.

Mrs.

Patterson, this is why there are no more letters mentioning Sarah.

This is why she disappeared from the family record.

They had no choice.

Did they say where they took her? To a suitable home, according to the society, but there’s no name, no location, just that she was removed.

Morgan rubbed her eyes, exhausted and furious.

I’m going to find out what happened to her.

The Society for Organizing Charity kept records.

If they placed her somewhere, there’s a paper trail.

Morgan.

Mrs.

Patterson’s voice was thick with emotion.

Thomas and Ruth kept that photograph.

They kept it even after Sarah was taken away.

They could have destroyed it.

could have tried to forget, but they kept it and they hid her in the picture where she’d be safe.

Safe from people who would judge them, safe from history that wouldn’t understand.

They were protecting her, even in memory.

Morgan looked at the restored photograph on her screen, at the small figure sitting with the family who had loved her enough to risk everything.

Then, we owe it to them to bring her back into the light, to let the world know what they did and what was done to them.

The Philadelphia Society for Organizing Charity had dissolved in 1934, but its records had been transferred to the city archives.

Morgan submitted a formal research request, explaining that she was investigating a specific case from 1902 involving a child named Sarah.

The archist, a young woman named Jessica, called her 2 days later.

“I found the file,” Jessica said.

“And Miss Chen, there’s a lot here.

” Morgan arrived at the archives within the hour.

Jessica led her to a private research room and set a cardboard box on the table.

Inside were folders, each containing case files from the early 1900s.

One folder was marked Parker Household, Lombard Street, case number 1902, 147.

Morgan opened it with careful hands.

The first document was a formal complaint dated January 10th, 1902, signed by Henrietta Worthington.

The language was flowery, but the message was clear.

A white child was being improperly influenced by living with a colored family, and immediate action was required.

The next document was an interview report with Thomas and Ruth Parker conducted by Mrs.

Adelaide Crane herself.

Morgan read Ruth’s words recorded by the society investigator.

Mrs.

Parker states that the child Sarah came into their care in December 1896 following the death of her mother at the Philadelphia docks.

No identification was found on the mother and no family came forward to claim the child.

Mrs.

Parker insists they have cared for the child as their own, that she attends church regularly, receives moral instruction, and is loved as a member of the family.

When asked why they did not immediately surrender the child to proper authorities, Mrs.

Parker became emotional and stated, “She was crying and alone.

What Christian soul could walk away from a child in need?” The investigator’s notes written in the margin were clinical and cold.

Despite the apparent adequate physical care, it is the determination of this society that the child’s moral and social development is being compromised by her current placement.

Recommend immediate removal to a suitable foster home pending adoption by a respectable white family.

Morgan felt tears sting her eyes.

She could imagine Ruth Parker sitting across from this woman trying to explain love in terms that would make sense to someone who saw only race and propriety.

The next document was the removal order dated January 28th, 1902.

Sarah was taken from the Parker home and placed temporarily with the Philadelphia Home for Infants, a charity institution that served as a way station for children awaiting placement.

Then came the adoption record dated March 15th, 1902.

Sarah, age approximately 8, healthy and well-mannered despite previous unsuitable placement, adopted by Mr.

and Mrs.

Charles Brennan of Germantown.

Mr.

Brennan is a clerk with the railroad company.

Mrs.

Brennan has no children of her own and is eager to provide the child with proper Christian upbringing.

Morgan’s hands shook as she turned to the final document in the file, a follow-up report from April in 1902.

Mrs.

Crane had visited the Brennan household to check on Sarah’s adjustment.

The report noted, “The child is quiet and obedient, but does not seem to have formed an attachment to her new family.

” Mrs.

Brennan reports that Sarah asks repeatedly about Mama Ruth and Papa Thomas, and becomes distressed when told she must forget them.

Mrs.

Brennan is confident that with time and proper discipline, these unsuitable attachments will fade.

Morgan closed the file and sat back, her heartbreaking for the 8-year-old girl who had been ripped away from the only family she’d ever known.

Told that her love was wrong, that the people who had cherished her were unsuitable, she photographed every document, then asked Jessica, “Is there any way to trace what happened to Sarah after this after the adoption?” Jessica hesitated.

Adoption records from that era are sealed in Pennsylvania, but the Brennan lived in Germantown.

That’s a specific neighborhood.

If Sarah stayed with them, she might appear in later census records.

And if she married, there’d be a marriage certificate.

It’s a long shot, but she shrugged.

Sometimes we get lucky.

Morgan became a detective, piecing together the fragments of Sarah’s life after she was taken from the Parkers.

The 1910 census showed Sarah Brennan, age 16, still living with Charles and Adelaide Brennan in Germantown, listed as their adopted daughter.

Her occupation, none.

Her education, 8th grade completed.

The 1920 census showed no Sarah Brennan in the household.

Morgan’s heart sank.

Had she moved away, married, died? She expanded her search to marriage records, death certificates, city directories.

Days passed with no results.

Then on a rainy Wednesday afternoon, she found a marriage certificate from 1918.

Sarah Brennan to William Foster, both of Philadelphia.

Sarah’s age, 24.

William’s occupation, postal clerk.

Morgan traced them through subsequent census records.

In 1920, William and Sarah Foster lived in the Fairmont neighborhood with their infant son, Robert.

In 1930, they had three children, Robert, Margaret, and Joseph.

William worked for the post office.

Sarah was listed as a housewife, but it was the 1940 census that gave Morgan what she’d been hoping for, an address still in Philadelphia, and more importantly, Sarah was still alive at age 46.

Morgan reached out to Mrs.

Patterson with her findings.

Together, they began searching for Sarah’s descendants.

Robert Foster, Sarah’s eldest child, had died in 1995.

But Margaret Foster, had married and had children of her own.

After days of searching through online genealogy databases and obituaries, they found her.

Margaret Foster Coleman, age 87, living in a retirement community in suburban Philadelphia.

Morgan called the number listed.

An elderly woman answered, “Mrs.

Coleman, my name is Morgan Chen.

I’m a photo restorer and I’ve been researching your grandmother, Sarah Foster, formerly Sarah Brennan.

I believe I’ve discovered something important about her early life, and I’d like to speak with you about it, if you’re willing.

There was a long pause.

My grandmother died in 1967, Mrs.

Coleman said slowly.

I was only 14, but I remember her.

What is this about? Mrs.

Coleman, I believe your grandmother was raised by a black family in Philadelphia before she was adopted by the Brennan.

I have a photograph from 1899 that shows her with them.

I think she may have been taken from them against their will.

Another pause, longer this time.

Then can you come see me? I I think we need to talk in person.

Morgan and Mrs.

Patterson sat in Margaret Coleman’s small apartment.

The restored photograph spread on the coffee table between them.

Margaret stared at it for a long time, her weathered hands trembling slightly.

I knew there was something, she said finally.

My grandmother never spoke much about her childhood, but when she did, there was always this sadness in her voice.

She told me once that she’d been adopted, that her birth mother had died when she was very small.

But she said Margaret’s voice caught.

She said she’d had another mother, too.

A mother who sang to her and braided her hair and taught her to pray.

She said she’d been happy once before she had to leave.

Mrs.

Patterson reached across and took Margaret’s hand.

“We found letters,” Morgan said gently.

“From Ruth Parker to her sister.

She wrote about Sarah constantly, how she was growing, learning, laughing, how much they loved her.

” Ruth, Margaret repeated softly.

Grandmother used to say that name sometimes, especially near the end when her mind was starting to go.

I want to see Ruth, she’d say.

I want to go home to Ruth.

We thought she was confused, mixing up memories.

But she wasn’t, was she? She was remembering.

The Parkers kept this photograph, Mrs.

Patterson said, touching the image.

My family kept it for over a century.

They never forgot her.

Margaret wiped her eyes.

Tell me about them.

Tell me about the people who love my grandmother.

Morgan and Mrs.

Patterson spent the next two hours sharing everything they discovered.

Thomas, who worked at the docks and brought home a crying orphan because he couldn’t bear to leave her alone.

Ruth, who added Sarah’s name to the family Bible and fought to keep her when the authorities came.

Samuel and Grace, who had a little sister for a few precious years.

My grandmother married my grandfather in 1918.

Margaret said she was 24 and he was the kindest man, patient, gentle.

My mother told me once that Grandma Sarah chose him because he reminded her of someone from her childhood.

A man who was gentle and strong.

She touched Thomas’s face in the photograph.

Maybe this was who she remembered.

What happened after she was taken from them? Mrs.

Patterson asked.

Did she ever try to find them? Margaret shook her head slowly.

I don’t think she could.

The Brennan, her adopted parents, they were strict.

Grandmother told me once that they punished her when she talked about her old family.

They told her it was shameful, that she should be grateful to have been saved from that situation.

Eventually, she learned not to speak about it.

But she never forgot, Morgan said.

She never forgot, Margaret confirmed.

And now I understand why.

Mrs.

Patterson, you said the Parkers were your ancestors.

Thomas and Ruth were my great great grandparents.

Samuel was my great-grandfather.

Margaret smiled through her tears.

Then we’re connected.

Sarah was their daughter, even if the law didn’t recognize it.

That makes us what? Some kind of cousins? Mrs.

Patterson laughed and cried at the same time.

It makes us family.

Three months later, on a bright Saturday morning in May, two families gathered at the restored grounds of the African Episcopal Church of St.

Thomas in Philadelphia.

Morgan had arranged everything, working with the church to organize what she called a commemoration ceremony, a chance to finally honor the story that had been hidden for so long.

The pastor, Reverend Williams, stood before the assembled group.

Mrs.

Patterson was there with three generations of her family, children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren of Samuel and Grace Parker.

Margaret Coleman sat in the front row, surrounded by her own children and grandchildren.

Sarah’s legacy carried forward through time.

We gather today, Reverend Williams began, to remember and honor a love that transcended the barriers placed by society.

In 1896, Thomas and Ruth Parker opened their home and hearts to a child who needed them.

They didn’t ask what color her skin was.

They didn’t worry about what the world would say.

They simply saw a little girl who needed a family and they gave her one.

Morgan displayed their restored photograph on a large screen.

All five figures clear and visible now.

Sarah sat at the front, her small face solemn but present, forever captured in the moment when she belonged.

For 6 years, Sarah was a Parker, the Reverend continued.

She was baptized here in this church.

She learned to read from Ruth’s Bible.

She played with her brother and sister.

She was loved fully and completely.

When she was taken away, it wasn’t because she wasn’t cared for.

It was because the world couldn’t accept that love doesn’t see color, that family is built not by blood alone, but by choice and commitment.

Mrs.

Patterson stood and approached the podium, holding a framed copy of the restored photograph.

My great great grandparents, Thomas and Ruth, kept this picture for the rest of their lives.

They never spoke about Sarah to anyone outside the family.

It was too painful, too dangerous in those times.

But they kept her image, kept her in their hearts.

Today, we’re bringing her story back into the light.

We’re saying her name.

Sarah Parker.

Sarah Parker, Margaret Coleman echoed from her seat, her voice strong despite her tears.

The congregation repeated it.

Sarah Parker.

Aw.

Morgan felt her own tears falling freely as she watched the two families embrace.

Descendants of the Parkers and descendants of Sarah brought together across the span of 125 years by a photograph and the love it represented.

After the ceremony, Margaret approached the photograph display and stood before it for a long time.

“She looks happy here,” she said to Morgan.

“In all the photos I have of my grandmother as an adult, she’s smiling, but there’s always something behind her eyes, a sadness, a loss.

But here, even though the picture is formal and she’s so young, there’s peace on her face.

She was home.

She was home,” Morgan agreed.

Mrs.

Patterson joined them, and the three women stood together looking at the restored image.

“We’re going to make sure this story is preserved, Mrs.

Patterson said, “The church is creating a permanent exhibit about Thomas and Ruth and Sarah, and we’re submitting their story to the historical society, so it becomes part of the official record.

” “My grandmother deserves to be remembered,” Margaret said.

“But so do Thomas and Ruth.

They risked everything to love a child who wasn’t supposed to be theirs.

That’s heroism.

That’s what the world needs to know.

” As the morning turned to afternoon, the families shared a meal together in the church hall.

Children who’d never met before played together, their laughter echoing off the walls.

Stories were exchanged, memories of Sarah, stories about Thomas and Ruth that had been passed down through generations.

Morgan watched it all, her heart full.

She’d started this project thinking she was simply restoring an old photograph.

But she’d done something far more important.

She’d restored a family, brought a hidden story into the light, and proven that love, real, sacrificial, courageous love, can survive, even when the world tries to erase it.

The restored photograph now hung in two homes, in Mrs.

Patterson’s living room and in Margaret Coleman’s apartment.

And in the church archive, it was displayed with a caption that read, “Thomas and Ruth Parker with their children, Samuel, Grace, and Sarah, 1899.

A family united by love, separated by injustice, reunited by memory.

May their story never be forgotten.

Sarah had finally come

News

Pope Leo XIV SILENCES Cardinal Burke After He REVEALED This About FATIMA—Vatican in CHAOS!

A Showdown in the Vatican: Cardinal Burke Confronts Pope Leo XIV Over Fatima Revelations In a dramatic turn of events…

ARROGANT REPORTER TRIES TO HUMILIATE BISHOP BARRON ON LIVE TV — HIS RESPONSE LEAVES EVERYONE STUNNED When a Smug Question Turns Into a Public Trap, How Did One Calm Answer Flip the Entire Studio Against Its Own Host? A Live Broadcast, a Loaded Accusation, and a Moment of Brilliant Composure Now Has Millions Replaying the Exchange — Click the Article Link in the Comment to Watch the Scene Everyone Is Talking About.

Bishop Barron Confronts Hostile Journalist in a Live TV Showdown In a gripping encounter that captivated audiences, Bishop Robert Barron…

Angry Protesters Disrupt Bishop Barron’s Mass… His Response Moves Everyone to Tears

A Transformative Encounter: Bishop Barron’s Unforgettable Sunday Mass What began as an ordinary Sunday Mass at the cathedral took an…

Bishop Barron demands Pope Leo XIV’s resignation in fiery speech — world leaders respond

A Historic Confrontation: Bishop Barron Calls for Pope Leo XIV’s Resignation In an unprecedented turn of events, the Vatican finds…

Pope Francis leaves a letter to Pope Leo XIV before dying… and what’s written in it makes him cry.

The Emotional Legacy of Pope Francis: A Letter to Pope Leo XIV In a poignant moment of transition within the…

POPE LEO XIV BANS THESE 12 TEACHINGS — THE CHURCH WILL NEVER BE THE SAME AFTER THIS When Ancient Doctrine Is Suddenly Silenced, What Hidden Battle Is Tearing Through the Heart of the Vatican — and Why Are Believers Around the World Being Kept in the Dark? Secret decrees, quiet councils, and forbidden teachings now threaten to rewrite centuries of faith — Click the Article Link in the Comment to Discover What the Church Isn’t Saying.

Pope Leo XIV Challenges Tradition with Bold Ban on Twelve Teachings The Catholic Church stands on the brink of transformation…

End of content

No more pages to load