This 1888 photograph hides a detail historians completely missed until now.

The basement archives of the Charleston County Historical Society were cool and dim, illuminated by carefully positioned LED lights that wouldn’t damage the fragile documents stored there.

Dr.James Mitchell had spent the better part of his career in rooms like this, hunting through yellowed papers and faded photographs for fragments of stories that deserve to be told.

On a sweltering August afternoon in 2024, he was cataloging a recently acquired collection of commercial photographs from late 19th century Charleston.

Most were unremarkable.

Storefronts, street scenes, advertisements captured by itinerant photographers trying to make a living documenting the rapidly changing post-war South.

But one photograph made him pause.

Something about it catching his researchers instinct even before he consciously understood why.

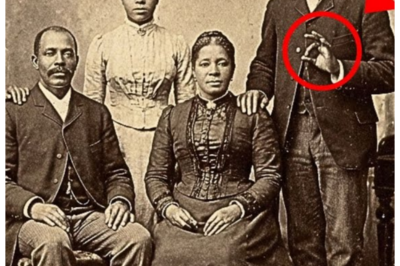

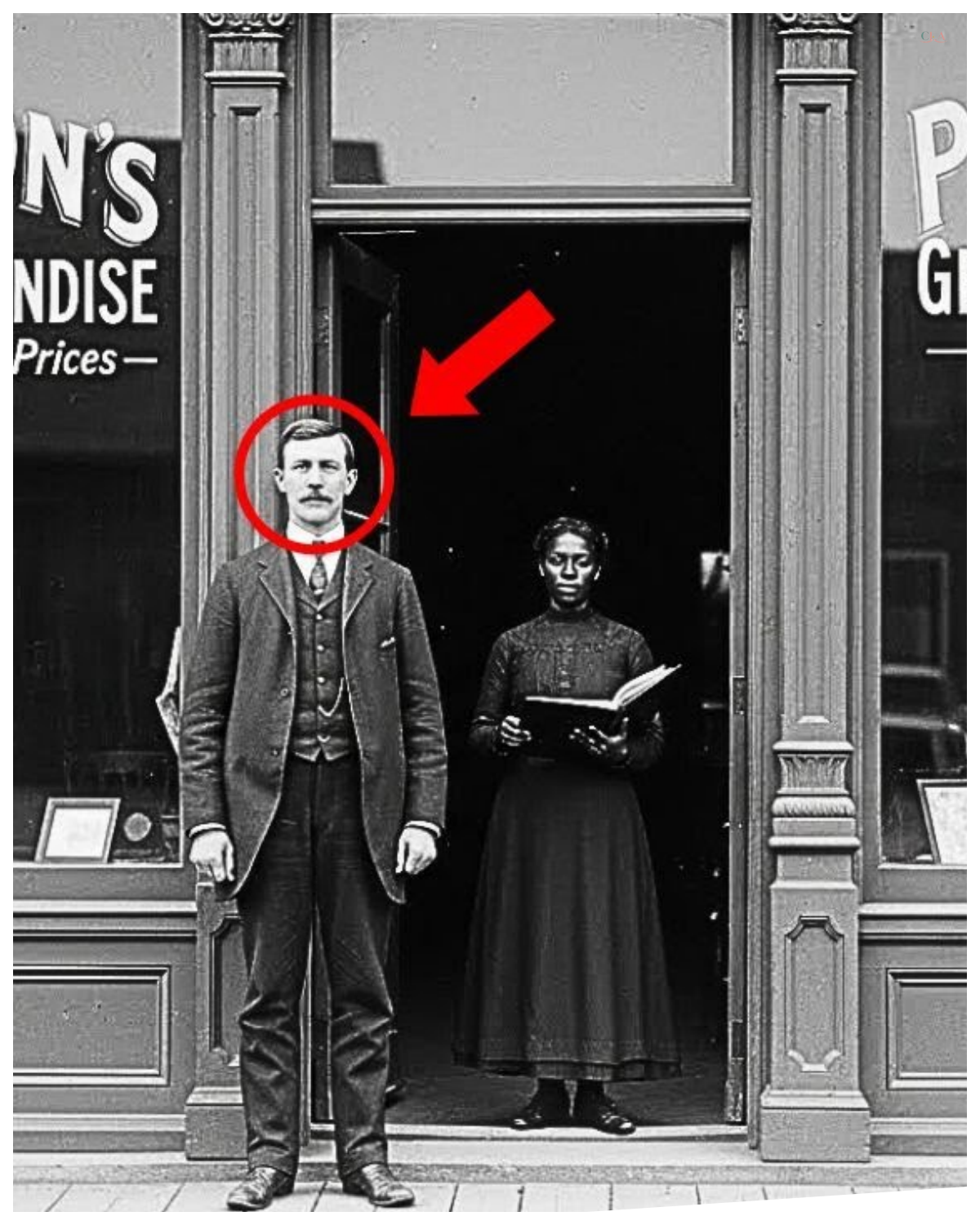

The image showed a general store, probably taken around 1898, based on the photographic technique and the style of goods visible in the windows.

The building was substantial, two stories of brick with large display windows flanking a central door.

Gold lettering on the window read, “Patterson’s General Merchandise.

Quality goods at fair prices.

” Through the windows, James could make out shelves stocked with fabric bolts, canned goods, tools, and other merchandise typical of a successful general store.

A white man stood prominently in the doorway, perhaps 45 years old, wearing a suit and vest, despite the obvious heat.

His posture was formal, proprieial, clearly the owner or manager posing for a photograph meant to advertise his business.

His name would be Patterson, James assumed, the name on the window.

But it was the figure partially visible in the doorway behind him that made James look closer.

A black woman stood just inside the store, positioned at an angle that suggested she hadn’t meant to be in the photograph at all, or perhaps had been deliberately positioned to appear incidental.

She wore a dark dress, simpler than the white man’s suit, but well-made and neat.

Her hair was pulled back in a careful bun.

She appeared to be in her mid-30s, and even in the faded photograph, James could see that she was strikingly beautiful with delicate features and an expression of composed intelligence.

At first glance, she might have been an employee, a clerk, or shop assistant captured accidentally while the photographer focused on the owner.

That wouldn’t be unusual for the period.

Many black women worked in shops owned by white men, particularly in Charleston, where the postwar economy had created some opportunities for employment, if not equality.

But something about her positioning bothered James.

She wasn’t standing like an employee waiting for instructions or trying to stay out of the frame.

She was standing like someone observing, assessing, perhaps even directing.

Her body language suggested authority rather than difference.

Despite the racial hierarchy that would have governed every interaction in 1898 Charleston, James pulled out his magnifying glass and examined the photograph more closely.

The woman’s hands were visible, resting on what appeared to be a ledger or accountbook.

Her posture was straight, confident, and her gaze, even across more than a century, seemed to look directly through the camera with an expression that was anything but subservient.

He flipped the photograph over, hoping for an inscription or identification.

On the back, in faded pencil, someone had written Patterson Store, King Street, 1898.

Nothing about the woman, no name, no explanation of her presence, just the store and the date.

James returned the photograph to its protective sleeve and added it to his digital scanning queue.

James couldn’t stop thinking about the photograph.

Over the next 3 days, it kept pulling at his attention as he cataloged the rest of the collection.

There was something about that woman’s expression, about the way she held that ledger, about her positioning in the doorway that suggested she was more than just an employee captured by accident.

Finally, he gave into his curiosity and began investigating.

Patterson’s general merchandise on King Street in 1898.

That was a starting point.

James had access to extensive property records for Charleston, digitized as part of a preservation project funded by the city and various historical foundations.

He pulled up the database and searched for King Street properties with commercial designations.

In the 1890s, he found the store easily enough.

237 King Street, listed in the 1898 city directory as Patterson’s general merchandise William Patterson proprietor.

The property record showed that William Patterson had acquired the building in 1895, purchasing it from a previous owner who’d operated a dry goods store there since the 1870s.

James cross referenced William Patterson’s name with other records.

The 1900 census listed him as age 47, white, married with two children.

Occupation: merchant.

Property value $8,000, a substantial sum, suggesting a successful business.

Everything seemed straightforward.

But something nagged at James.

He’d researched enough postreonstruction Charleston to know that property ownership and business operations were often more complex than they appeared on paper.

The racial codes and legal restrictions of the era had created a shadow economy where black entrepreneurs sometimes operated through white intermediaries, where ownership was disguised, where official records deliberately obscured actual power dynamics.

He decided to dig deeper into the property records, looking not just at who owned the building, but at the financial transactions, the mortgages, the tax payments.

This kind of detailed research was tedious, requiring cross- refferencing multiple databases and tracking down original documents.

But James had learned that the most interesting stories were usually hidden in the boring paperwork.

After 2 days of searching, he found the anomaly.

The property taxes for 237 King Street were paid not by William Patterson, but by someone else, a woman named Charlotte Hayes.

The payments were documented consistently from 1895 through 1902.

Always paid in full and on time.

Always with Charlotte Hayes’s name on the receipt, despite William Patterson being listed as the legal owner, James felt the familiar thrill of discovery.

This was the thread he needed to pull.

Who is Charlotte Hayes and why was she paying the property taxes on a store supposedly owned by William Patterson? He searched for Charlotte Hayes in the census records and found her.

Charlotte Hayes, black, age 34 in 1900, listed as domestic servant in the census occupation field.

She lived in a modest house on Street, several blocks from King Street, and was listed as head of household with no husband present, domestic servant.

but she was paying property taxes on an $8,000 commercial building.

James requested access to the Charleston County tax records, which were stored partially in digital format and partially in original ledgers that had to be examined in person.

He spent two full days in the climate controlled vault where the original documents were kept, carefully turning pages and photographing entries.

The tax records revealed a pattern.

Charlotte Hayes had been paying property taxes on 237 King Street since 1895, always in cash, always documented with her signature, a careful, educated hand that spelled her name in clear script.

But she also paid taxes on two other properties, the house on Street where she lived, and another commercial building on Meeting Street that was officially owned by a white man named Robert Johnson.

James searched for Robert Johnson and found another merchant in the city directory operating a habeddasherie at the Meeting Street address.

The pattern was becoming clear, but James needed more evidence to confirm his theory.

He turned to bank records, which were harder to access, but not impossible.

Charleston had several banks that had survived from the 19th century, and some had donated their historical records to various institutions.

James made inquiries and was eventually directed to a collection at the South Carolina Historical Society that included ledgers from the Palmetto Savings Bank, which had operated from 1888 to 1910.

The ledgers were handwritten, dense with entries recording deposits, withdrawals, loans, and account balances.

James worked methodically through the 1890s entries, searching for either Charlotte Hayes or William Patterson.

He found Charlotte Hayes first.

She had opened an account in 1889 with a deposit of $300, a significant sum for someone who would later be listed in the census as a domestic servant.

The account showed regular deposits throughout the 1890s, ranging from $20 to $100 with occasional large withdrawals that coincided with property purchases and tax payments.

By 1900, Charlotte Hayes’s account balance was over $12,000.

James sat back in his chair, stunned.

$12,000 in 1900 would be equivalent to roughly $400,000 in 2024.

This was not the account of a domestic servant earning a few dollars a week.

This was the account of a successful businesswoman.

He searched for William Patterson’s records and found a much more modest account opened in 1895, right when he acquired the King Street store with regular small deposits that looked like salary payments rather than business profits.

Patterson wasn’t the successful merchant he appeared to be.

He was being paid by someone else to act as the public face of a business he didn’t actually control.

James needed to understand the full scope of what Charlotte Hayes had built.

He returned to the property records and began a systematic search for any properties where she paid taxes, even though someone else was listed as the legal owner.

Over the next week, he found five properties, two commercial buildings and three residential properties, all officially owned by white men, but with taxes paid consistently by Charlotte Hayes.

She had built a small real estate empire disguised behind white intermediaries.

To understand what Charlotte Hayes had accomplished, James needed to understand the legal and social constraints she’d been operating under.

He was familiar with the general outlines of Jim Crow, South Carolina, but he needed specifics, exactly what restrictions existed in Charleston in the 1890s regarding black property ownership and business operations.

He spent several days researching South Carolina law codes from the period, as well as city ordinances specific to Charleston.

What he found was a systematic effort to exclude black citizens from economic opportunity and wealth accumulation.

While the law didn’t explicitly forbid black property ownership after emancipation, a web of informal restrictions and discriminatory practices made it extremely difficult.

Black buyers faced higher interest rates on mortgages, were routinely denied loans by whiteowned banks, and could be denied the right to purchase property in certain areas through restrictive covenants and informal agreements among white property owners.

For black entrepreneurs, the situation was even more complicated.

Opening a business in a prime commercial location, particularly in the retail sector serving white customers, was nearly impossible.

White customers wouldn’t patronize black-owned businesses in most cases, and white suppliers often refused to sell goods to black merchants or charged inflated prices.

The result was an economic system designed to keep black citizens in positions of dependency and subservience, limited to low-wage labor regardless of their skills or ambitions.

Yet, Charlotte Hayes had somehow circumvented this entire system.

She’d accumulated significant capital, purchased prime commercial properties, and operated successful businesses, all while remaining invisible in the official records that would have made her a target for white violence and economic retaliation.

James needed to understand how she’d done it.

And more importantly, he needed to understand who she really was.

He returned to the 1900 census and looked more carefully at Charlotte’s entry.

Listed as domestic servant, page 34, black, head of household.

born in South Carolina.

Both parents born in South Carolina.

She could read and write.

The census taker had noted that, which was significant given that many formerly enslaved people had been denied education.

But domestic servant was clearly a cover story, a safe occupation to list that wouldn’t draw attention or raise questions about how she’d accumulated wealth.

James searched for earlier records, hoping to trace Charlotte’s life before she appeared as a property owner in 1895.

The 1890 census records had been destroyed in a fire, but the 1880 census survived.

He found a Charlotte Hayes, age 14, listed as living with her mother, Elizabeth Hayes, who worked as a laress.

They lived in a poor section of Charleston, and the young Charlotte was listed as helping her mother with laundry work.

From laress’s daughter to owner of multiple properties in 15 years.

how James decided to look for Charlotte Hayes in business directories and advertisements from the 1880s and early 1890s, hoping to trace how she’d accumulated her initial capital.

Business directories were organized by occupation and location.

And he started with service occupations that a young black woman might have entered.

Laundress, domestic worker, seamstress.

He found her in an 1888 business directory.

Hayes, Charlotte, dressmaker and seamstress, Street.

a dress maker.

That made sense as a path to accumulating capital.

Skilled seamstresses could earn decent money, particularly if they attracted wealthy clients who paid well for custom garments.

And dressmaking was one of the few businesses a black woman could operate relatively openly without facing the same level of discrimination as other commercial ventures.

James searched for advertisements and found several in Charleston newspapers from the late 1880s and early 1890s.

Miss Charlotte Hayes, fine dress making and alterations, ladies garments of highest quality, Street.

The advertisements were small but consistent, appearing regularly in the women’s pages of local papers.

James noted that they were placed in papers read by both white and black communities, suggesting Charlotte had built a diverse clientele.

He found references to her work in surprising places.

A society column from 1889 mentioned that several ladies of our acquaintance wore gowns created by the talented Miss Hayes to a prominent charity ball.

Another column from 1891 praised the exceptional needle work of Miss Hayes, whose skill rivals, that of the finest European dress makers.

Charlotte Hayes had been more than just a competent seamstress.

She’d been exceptional, skilled enough that wealthy white women had been willing to overlook racial prejudice to wear her creations.

and she’d been smart enough to turn that skill into capital, saving her earnings and investing them strategically.

But dressmaking income alone, even with wealthy clients, wouldn’t have been enough to accumulate $12,000 and purchase multiple properties.

There had to be something else, some additional source of income or investment strategy that had accelerated her wealth accumulation.

James thought about the photograph again, about Charlotte standing in the doorway of Patterson’s general merchandise with that ledger in her hands, that expression of authority and assessment.

She hadn’t been just the dress maker who’d invested in real estate.

She’d been the architect of something more sophisticated, a system for operating businesses that served white customers while remaining hidden behind white intermediaries.

He needed to understand how the system worked, and he needed to find evidence that connected Charlotte directly to the management of those businesses, not just their ownership.

James returned to the photograph, studying it with fresh eyes.

Charlotte Hayes stood in the doorway, holding what he’d initially thought was a ledger or account book.

He enhanced the digital scan, adjusting contrast and sharpness, zooming in on her hands and the object she held.

It was definitely a ledger.

He could make out the ruled lines of accounting pages, the neat columns of figures.

But more importantly, he could now see that Charlotte’s posture wasn’t that of someone casually holding a book.

Her fingers were positioned as if she’d been interrupted while actively working, in the middle of recording transactions or reviewing accounts.

James had researched enough business history to understand the significance of who controlled the ledgers.

The person who kept the books controlled the business regardless of whose name was on the deed or the storefront.

If Charlotte Hayes was keeping the accounts for Patterson’s general merchandise, she wasn’t just a silent investor.

She was the actual operator, the person making decisions about inventory, pricing, credit, and profits.

He needed to find those ledgers, or at least find additional evidence of Charlotte’s active role in managing the businesses officially owned by her white intermediaries.

James contacted the Charleston County Records Office and inquired about business records from closed establishments.

It was a long shot.

Most 19th century business papers had been lost or destroyed, but sometimes surprising things survived in unexpected places.

The archivist he spoke with was intrigued by his research and promised to search through uncataloged collections.

Two weeks later, James received an email.

Found something that might interest you.

Box of miscellaneous business papers from meeting street properties.

Donated 1973.

Never fully processed.

Includes ledgers.

James drove to the records office the next morning, barely able to contain his excitement.

The archist brought out a dusty cardboard box labeled simply meeting St.

Commercial, a mature papers, 1890s, 1900s.

Inside were three leatherbound ledgers, water stained but readable, along with loose receipts, correspondents, and inventory lists.

James pulled on cotton gloves and opened the first ledger carefully.

The handwriting was precise, elegant, with numbers aligned in perfect columns.

The entries recorded daily transactions for a business that sold men’s clothing and accessories.

Robert Johnson’s habeddasherie, James realized, the meeting street property where Charlotte paid the taxes.

But the handwriting wasn’t Robert Johnson’s.

James had seen Johnson’s signature on legal documents, and it was crude, barely literate.

This handwriting belonged to someone educated, someone with practice keeping detailed accounts.

James turned to the inside cover of the ledger, hoping for a name or identification.

In the same elegant handwriting, someone had written ch January 1896.

CH Charlotte Hayes.

He carefully photographed every page of all three ledgers, documenting two years of daily operations for the habedasherie.

The entries showed sophisticated business management, careful inventory control, strategic pricing, extension of credit to reliable customers, firm collection of debts.

With the ledgers as evidence of Charlotte’s active management, James shifted his research to understanding the white men who’d served as her public faces.

William Patterson, Robert Johnson, and three others whose names appeared on property deeds, but whose tax payments came from Charlotte Hayes.

He started with William Patterson, the man in the photograph.

Property records showed Patterson had arrived in Charleston in 1894, migrating from rural Georgia.

Before 1895, there was no evidence he’d ever operated a business or owned significant property.

He’d worked as a clerk in someone else’s store, earning modest wages.

Then suddenly in 1895, he purchased a valuable commercial building and opened a general store with no clear source for the capital required.

The timing coincided exactly with Charlotte Hayes beginning to pay the property taxes.

James found Patterson’s death certificate from 1903.

Cause of death, pneumonia.

Occupation listed, store clerk, not owner, not merchant, clerk.

Even in death, the official record obscured the true relationship.

Robert Johnson’s story was similar.

A working-class white man with no business experience who suddenly owned a habeddasherie in a prime location.

Tax records showed Charlotte paying the bills.

Johnson died in 1901 and his death certificate listed his occupation as shop manager, again, not owner.

The pattern was consistent across all five properties.

Charlotte had recruited white men who needed income, men who were willing to serve as legal owners and public faces in exchange for what appeared to be salary payments documented in her bank records.

These men would interact with white customers, white suppliers, white landlords in cases where Charlotte leased rather than owned buildings, and white authorities.

They provided the racial cover that allowed Charlotte’s businesses to operate in spaces where blackowned businesses would have been rejected or destroyed.

It was an ingenious system, but also a precarious one.

Charlotte had to trust these men not to betray her, not to claim actual ownership, not to reveal the arrangement.

The fact that the system worked for years suggested she’d chosen carefully and managed the relationship skillfully.

James found one piece of evidence that revealed how Charlotte maintained control.

In the estate records for Robert Johnson, there was a curious document, a signed statement dated 1897 in which Johnson acknowledged that while he was the legal owner of the habeddashery property, he held it in trust for the benefit of another party to be transferred according to previously established arrangements.

The document didn’t name Charlotte Hayes explicitly, but James understood its purpose.

It was insurance, a legal acknowledgement that would allow Charlotte to claim the property if Johnson died or tried to claim actual ownership.

Similar documents probably existed for the other properties, though James hadn’t found them yet.

As James researched deeper into Charlotte Hayes’s business operations, he began to notice another pattern.

She hadn’t operated in isolation.

There was evidence of a broader network of black entrepreneurs in Charleston who were using similar strategies, disguising their ownership and operations behind white intermediaries.

He found property tax records showing multiple properties where the legal owner was white, but taxes were paid by black individuals.

He found business ledgers and other archival collections showing the same elegant, educated handwriting, managing books for businesses officially owned by whites.

The system Charlotte had pioneered or participated in wasn’t unique to her.

It was part of a shadow economy, a network of mutual support and shared strategy among black business people navigating Jim Crow restrictions.

James discovered references to informal meetings held at black churches and mutual aid societies where business matters were discussed.

Minutes from an 1897 meeting at Emanuel Ame Church mentioned strategies for property acquisition and management given current legal constraints.

Coded language for exactly what Charlotte and others were doing.

He found evidence that Charlotte herself had helped other black entrepreneurs establish similar arrangements.

A letter from 1899 preserved in a family collection donated to the Avery Research Center mentioned Miss Hayes’s kind assistance in arranging our business affairs and thanked her for introductions that made our enterprise possible.

Charlotte Hayes wasn’t just a lone entrepreneur.

She was a leader and mentor within a community of black business people who were collectively resisting and circumventing the economic oppression of Jim Crow.

They were building wealth, acquiring property, operating businesses, and laying foundations for future generations.

all while remaining officially invisible in the records that white authorities consulted.

The photograph took on new meaning with this understanding.

Charlotte standing in that doorway wasn’t just ironic or subversive.

It was deliberate documentation of her actual role, preserved in an image that white viewers would misinterpret as showing an employee, but that knowing viewers would understand correctly.

James wondered who else in Charleston’s black community would have understood what they were really seeing when they looked at that photograph.

Who else would have recognized Charlotte Hayes and known that despite William Patterson’s prominent position, she was the one who really owned and operated that store.

The photograph was a secret hidden in plain sight, a truth preserved through misdirection and assumption.

White viewers saw what they expected, a white store owner and a black employee, but the reality was exactly the opposite.

James had documented Charlotte Hayes’s business empire and understood the system she’d created, but he wanted to know what had happened to her after 1902, when the documentary trail became harder to follow.

He also wanted to find her descendants to tell them about their ancestors extraordinary achievements.

He started with death records, searching Charleston County for Charlotte Hayes.

He found her death certificate from 1924.

Charlotte Hayes, age 58, cause of death listed as heart failure.

Her occupation was still listed as domestic servant, maintaining the fiction until the end.

She was buried in a cemetery on the outskirts of Charleston that served the black community.

But the death certificate included next of kqin a daughter Rose Hayes Anderson living at an address on Street, the same street where Charlotte had owned her house.

James traced Rose through subsequent records.

The 1930 census listed her as a school teacher aged 38, married to a carpenter named Thomas Anderson.

They had three children.

Rose had clearly benefited from her mother’s wealth accumulation, being able to pursue education and a professional career rather than domestic labor.

Through genealological databases and census records, James traced Rose’s descendants forward through the generations.

He found grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and great great grandchildren scattered across the country.

Many had left Charleston during the Great Migration, moving north for better opportunities, but several branches of the family remained in South Carolina.

James spent weeks making contact, carefully explaining his research, and asking if family members would be willing to share what they knew about Charlotte Hayes.

The responses varied from enthusiastic to cautious to completely surprised.

Some descendants had known Charlotte was good with business, but many had no idea of the scope of what she’d accomplished.

One of Charlotte’s great great-granddaughters, a woman named Diane Morrison, who lived in Columbia, South Carolina, had inherited a box of family papers that included several items belonging to Charlotte.

When James drove to Columbia to meet her, Diane brought out a small leather journal.

“My grandmother gave this to me before she died,” Diane explained.

She said it belonged to her grandmother, Charlotte, and that I should keep it safe because it told an important story.

The journal was Charlotte’s personal account book, separate from the business ledgers.

It recorded her income, expenses, investments, and property acquisitions from 1889 to 1910.

The entries were brief but clear, showing exactly how Charlotte had built her wealth, starting with dressmaking income, investing in small properties, using rental income to fund business ventures, always reinvesting profits rather than spending on luxuries.

But the journal also included personal notes, brief observations that revealed Charlotte’s thinking and strategy.

James stood in the Charleston Museum’s new exhibition hall, looking at the photograph that had started his research journey eight months earlier.

It was now the centerpiece of an exhibition titled Hidden Entrepreneurs: Black Business in Jim Crow Charleston.

Mounted prominently with dramatic lighting that made Charlotte Hayes’s figure in the doorway impossible to miss.

The exhibition included the photograph, the ledgers James had found, pages from Charlotte’s personal journal, property records, tax receipts, and contemporary photographs of the buildings she’d owned, some still standing, others long demolished.

Interactive displays explained the Jim Crow system that had made her deception necessary, and the ingenious strategies she and others had used to build wealth despite legal and social barriers.

Most powerfully, the exhibition featured testimony from Charlotte’s descendants, including Diane Morrison, who donated Charlotte’s journal to the museum, so others could learn from her ancestors story.

The exhibition opening drew an enormous crowd, historians, community members, descendants, not just of Charlotte, but of other black entrepreneurs who’d operated similar businesses, journalists from local and national media outlets.

The story of Charlotte Hayes had struck a chord, revealing a hidden history of resistance, ingenuity, and resilience that complicated simple narratives about black economic history in the Jim Crow South.

James watched as visitors studied the photograph, reading the interpretive text that explained what they were really seeing.

Not a white store owner and his black employee, but a black business woman who owned the store and the white man she paid to serve as its public face.

My great great-grandmother owned five commercial properties and operated multiple businesses in 1898 Charleston, Diane Morrison said during her remarks at the opening.

But she had to pretend to be a domestic servant.

She had to hide her success, disguise her intelligence, operate through intermediaries because the law and society wouldn’t let her succeed openly as a black woman.

But she did it anyway.

She found a way.

Diane paused looking at the photograph.

When I look at this image now, I see what she was really doing.

She’s standing in that doorway documenting her achievement, making sure there would be evidence for future generations, even if the official records lied about who she was.

She’s looking at the camera like she’s looking at us, at the future, saying, “I was here.

I built this.

Don’t let them erase me.

” The crowd applauded, and James felt the satisfaction of historical work well done, bringing hidden stories to light, correcting the record, honoring people whose achievements had been deliberately obscured.

After the formal program, James stood near the photograph as visitors examined it closely, watching their expressions change as they understood what they were really seeing.

A young black woman, perhaps college-aged, stared at Charlotte Haye’s face for a long time.

“She looks so confident,” the young woman finally said to James, even knowing she had to hide everything she’d accomplished.

Even standing behind this white man pretending to own her store, she looks confident, proud, like she knew exactly what she was doing and knew she’d won.

“I think she did know,” James replied.

The system was designed to stop people like her, but she was smarter than the system.

She found the cracks and exploited them.

She built wealth and security for her family despite everything stacked against her.

“How many others were there?” the young woman asked.

“How many other Charlotte Hayes were there that we don’t know about because their photographs didn’t survive or nobody looked closely enough?” “Probably hundreds,” James admitted.

“Maybe thousands across the South.

The documentary evidence is fragmentaryary because they had to hide their success.

But this photograph, Charlotte’s Ledgers, her journal, they prove it was happening.

And that means we should look more carefully at other photographs, other records, asking ourselves if the obvious interpretation is really the correct one.

The young woman nodded slowly, still studying Charlotte’s face.

Thank you for finding her story, for seeing what others missed.

As the evening wore on, and the crowd thinned, James took one last look at the photograph before leaving.

Charlotte Hayes stared back at him across 126 years, her expression composed and knowing, her hands resting on the ledger that proved her real role despite all the official lies.

For more than a century, historians had looked at this photograph and seen exactly what white supremacy had wanted them to see.

A white business owner and a black employee, natural and unremarkable.

They’d missed the detail that Charlotte Hayes had hidden in plain sight.

her confident posture, her proprietorial positioning, her hands on the business records, her expression that said she knew exactly who really owned and operated that store.

But secrets James had learned throughout his career are meant to be discovered.

And some stories are too important, too powerful, too fundamentally inspiring to remain hidden forever.

Charlotte Hayes had made sure of that when she stood in that doorway in 1898 and let the photographer capture her truth, preserved in silver and light, waiting for someone to finally understand what they were really seeing.

The detail historians had completely missed wasn’t small or hidden.

It was right there in Charlotte’s confident stance in her hands on those ledgers, in her knowing expression that looked straight through the camera at a future she hoped would someday understand.

They’d missed it because they’d seen what they expected to see.

What the racial hierarchy of Jim Crow told them must be true.

But the truth had been there all along, waiting 126 years to be recognized, waiting for someone to look closely enough, questioned carefully enough, and refused to accept the obvious explanation when the evidence suggested something far more remarkable.

Charlotte Hayes had been erased from the official record, but she’d left clues.

And now finally her story was told not as a domestic servant in someone else’s narrative, but as the brilliant entrepreneur and community leader she’d actually been.

A woman who’d built an empire in the shadows and made sure the light would eventually find

News

This Portrait of Two Friends Seemed Harmless — Until Historians Spotted a Forbidden Symbol Hidden Between Them and Everything Fell Apart ⚠️ — At first it was just two smiling companions shoulder-to-shoulder in stiff old-fashioned suits, the kind of wholesome image you’d frame without a second thought, but a closer scan revealed a tiny, outlawed mark tucked into the shadows, and suddenly the photo wasn’t friendship… it was rebellion, secrecy, and a message never meant to survive the century 👇

This portrait of two friends seemed harmless until historians noticed a forbidden symbol. The afternoon sun filtered through the tall…

Experts Thought This 1910 Studio Photo Was Peaceful — Until They Zoomed In and Saw What the Girl Was Holding, and the Entire Room Went Cold 📸 — At first it looked like another gentle Edwardian portrait, lace dress, soft lighting, polite smile, but when archivists enhanced the image they noticed her tiny fingers clutching something oddly deliberate, something that didn’t belong in a child’s hands, and suddenly the sweetness curdled into dread as historians realized this wasn’t innocence… it was a clue 👇

Experts thought this 1910 studio photo was peaceful until they saw what the girl was holding. Dr.Maya Johnson’s hands trembled…

This Portrait from 1895 Holds a Secret Historians Could Never Explain — Until Now It’s Finally Been Exposed in Stunning Detail 🖼️ — For more than a century it hung quietly in dusty archives, dismissed as another stiff Victorian pose, until a routine scan revealed a tiny, impossible detail that made experts freeze mid-sentence, because suddenly the calm expressions looked staged, the shadows suspicious, and the entire image felt less like art… and more like evidence 👇

The fluorescent lights of Carter and Sons estate auctions in Richmond, Virginia, cast harsh shadows across tables piled with forgotten…

It Was Just a Studio Photo — Until Experts Zoomed In and Saw What the Parents Were Hiding in Their Hands, and the Room Went Dead Silent 📸 — At first it looked like another stiff, sepia family portrait, the kind you pass without a second thought, but when historians enhanced the image and spotted the tiny, deliberate objects clutched tight against their palms, the smiles suddenly felt forced, the pose suspicious, and the entire photograph transformed from wholesome keepsake into something deeply unsettling 👇

The auction house in Boston smelled of old paper and varnished wood. Dr.Elizabeth Morgan had spent the better part of…

This Forgotten 1912 Portrait Reveals a Truth That Changes Everything We Thought We Knew — and Historians Are Panicking Over What’s Hidden in Plain Sight 🖼️ — It hung unnoticed for over a century, dismissed as polite nostalgia, until one sharp-eyed researcher zoomed in and felt their stomach drop, because the face, the object, the posture all scream a secret no one was supposed to catch, turning a dusty archive into a ticking historical bombshell 👇

This forgotten 1912 portrait reveals a truth that changes everything we knew until now. Dr.Marcus Webb had been working as…

Four Years After The Grand Canyon Trip, One Friend Returned Hiding A Dark Secret

On August 23rd, 2016, 18-year-olds Noah Cooper and Ethan Wilson disappeared without a trace in the Grand Canyon. For four…

End of content

No more pages to load