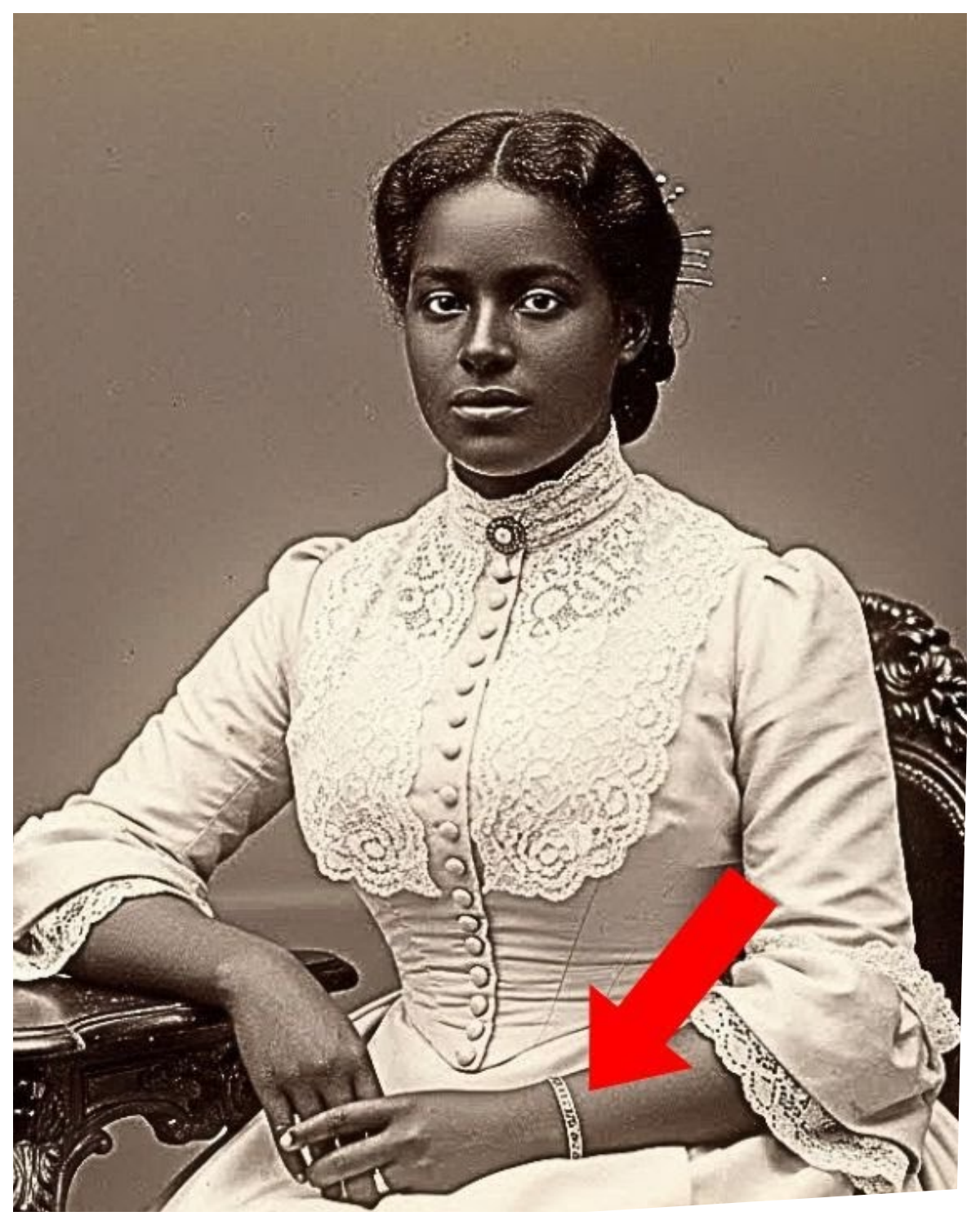

This 1889 studio portrait appears elegant until you notice what’s wrapped around the woman’s wrist.

Dr.Sarah Bennett had spent 17 years cataloging photographs at the Charleston Museum of History.

She thought she had seen everything the 19th century could offer.

Stern patriarchs and formal dress, fading tint types of Civil War soldiers, cabinet cards of society ladies posed in elaborate gowns.

None of them had ever made her hands tremble the way they did on this humid March morning.

The Whitmore family estate collection had arrived three months earlier, donated after the death of Margaret Whitmore, the last surviving member of one of Charleston’s oldest families.

Sarah had been working through the boxes methodically, documenting each image with the careful attention that had made her one of the most respected curators in South Carolina.

She opened a leather portfolio marked simply 1889 and carefully lifted out the photograph inside.

Her breath caught immediately.

The image showed a young black woman, perhaps 25 years old, seated in an ornate photography studio.

Everything about the portrait spoke of wealth and sophistication, the elaborate backdrop of painted columns and velvet drapery, the professional lighting that highlighted her elegant features, and most striking of all, the dress she wore.

It was exquisite, pale silk with intricate lace at the collar and cuffs, pearl buttons running down the bodice, the kind of gown that would have cost more than most working families earned in a year.

The woman’s posture was perfect.

her expression serene and dignified.

Her dark hair was styled fashionably, swept up and adorned with delicate pins.

She could have been any wealthy Charleston lady sitting for a formal portrait.

Except she was black, and this was 1889, only 24 years after the end of slavery.

Sarah pulled her magnifying glass closer, examining the details.

Formal studio portraits of well-dressed black women existed in this era.

Certainly, there were successful educators, business owners, and artists in the black community who could afford such luxuries.

But finding such a photograph in a wealthy white family’s personal collection was unusual enough to warrant closer inspection.

That was when she noticed it.

Around the woman’s left wrist, partially hidden by the pale silk sleeve, was a thin band of metal.

Sarah’s heart began to pound as she adjusted the magnifying glass.

It was not a bracelet.

The design was too utilitarian, too tight against the skin.

As she looked more carefully, she could see it was attached to a delicate chain that disappeared into the folds of the woman’s elaborate dress.

It was a shackle, an elegant, almost decorative shackle designed to blend with expensive jewelry, but a restraint nonetheless.

Sarah’s hands shook as she turned the photograph over.

On the back, written in faded brown ink, were four words that made her stomach turn.

Catherine, property of Whitmore.

24 years after the 13th Amendment had abolished slavery throughout the United States, someone in Charleston had commissioned a formal studio portrait of a black woman wearing chains and labeled her as property.

Sarah sat back in her chair, staring at the image.

This was not just a historical photograph.

It was evidence of a crime.

But more than that, it was proof of a woman’s existence.

A woman whose story had been deliberately hidden for over a century.

She reached for her phone with trembling fingers.

This discovery would change everything.

Sarah barely slept that night.

The image of Catherine’s face haunted her.

That carefully composed expression that she now understood was a mask hiding fear, anger, and desperation.

By dawn, Sarah was back at her desk at the museum, determined to find out who Catherine had been and what had happened to her.

She began with census records, the backbone of genealological research.

If Catherine had been in Charleston in 1889, there should be some trace of her in official documents.

She pulled up the 1890 federal census first, but immediately encountered a frustrating obstacle.

Most of those records had been destroyed in a 1921 fire at the Commerce Department, leaving historians with a massive gap in documentation for that crucial decade.

Sarah pivoted to the 1880 census instead.

If Katherine had been with the Whitmore family in 1889, perhaps she appeared in their household records 9 years earlier.

She found the Whitmore entry easily enough.

Richard Whitmore, age 42, occupation listed as merchant and landowner.

His address was 47 Meeting Street, one of Charleston’s most exclusive addresses in the heart of the historic district where only the wealthiest families resided.

The household included Richard’s wife, Ellaner, age 38, and their three children, Margaret, 16, Thomas, 14, and Elizabeth, 10.

Below the family members, the census listed five domestic servants, all black, all with ages, birthplaces, and occupations carefully noted.

There was Mary, age 45, cook, James, age 32, butler.

Rebecca, age 28, housemmaid.

Samuel, age 19, groundskeeper, and Ruth, age 51, laress.

But no, Catherine.

Sarah frowned at the screen.

Perhaps Catherine had arrived after 1880.

She opened Charleston city directories from the 1880s, thick volumes that listed residents, their occupations, and addresses.

The Whitmore entry appeared consistently year after year, but city directories rarely mentioned servants or other household members beyond the head of household.

She was about to close the 1887 directory when a small notation caught her eye.

See also Whitmore, R.

Summer residence, Adisto Island.

Adisto Island.

Sarah knew it well.

A barrier island about 40 miles south of Charleston that had been home to numerous rice and cotton plantations before the Civil War.

Many wealthy Charleston families had maintained summer properties there, escaping the city’s oppressive heat and the diseases that came with it.

By the 1880s, most of the plantations had been subdivided or abandoned, but some families still kept their island estates.

Sarah pulled up historical land records for Adisto Island.

The Whitmore family had owned a property called Magnolia Hall, a former rice plantation of 800 acres.

According to the records, they had retained ownership even after the Civil War, though the property was no longer being actively farmed by the 1880s.

She made a note to visit Edesto Island.

But first, she wanted to search newspaper archives.

She spent the next 3 hours combing through digitized editions of the Charleston News and Courier, the city’s primary newspaper in the 1880s.

Newspapers of that era regularly reported on the social activities of prominent families.

Dinner parties, charity events, business ventures, births, marriages, and deaths.

The Whitmore name appeared frequently.

Richard Whitmore was mentioned in business news, his textile import company apparently quite successful.

Elanor Whitmore appeared in society pages, hosting tees and supporting various charitable causes.

The children’s activities were occasionally noted.

Margaret’s piano recital, Thomas’s graduation from preparatory school.

But nowhere in any article or notice was there any mention of Catherine.

The absence itself was significant.

Someone had been deliberately kept invisible, erased from the public record while being documented in private photographs.

The drive to Adisto Island took Sarah through the low country landscape she had always found hauntingly beautiful.

Vast stretches of marsh grass turning gold in the afternoon sun.

Narrow bridges spanning tidal creeks.

Ancient live oaks draped with Spanish moss creating tunnels of shade along the roads.

But today, the beauty felt oppressive, knowing what secrets this landscape had once hidden.

Finding Magnolia Hall proved more difficult than she had anticipated.

The property was not listed on any current maps, and the first three people she stopped to ask for directions had never heard of it.

Finally, at a small general store near the center of the island, an elderly man restocking fishing supplies recognized the name.

Whitmore Place? He scratched his weathered face thoughtfully.

That burned down.

Must be 40 45 years ago now.

Lightning strike.

I think nobody ever rebuilt it.

The land’s still there, though, somewhere off Jungle Road.

All grown over with vegetation.

You researching history or something? Something like that, Sarah replied.

Can you tell me how to find it? His directions were vague.

About 2 mi down Jungle Road, look for a path on the left near where the big oak split in half.

But after 20 minutes of slow driving and careful observation, Sarah found what she was looking for.

A barely visible dirt track led off into dense vegetation, overgrown palmetto fronds, and wild vines nearly obscuring the entrance entirely.

She parked her car and continued on foot, pushing through the thick undergrowth.

The path was barely discernible, used perhaps occasionally by hunters or adventurous teenagers, but clearly not maintained in decades.

Mosquitoes buzzed around her face, and she heard the rustling of unseen creatures in the brush.

After about 10 minutes of walking, the vegetation suddenly opened up into a clearing.

The main house was gone, just as the man at the store had said.

Only the brick foundation remained, a rectangular footprint slowly being reclaimed by weeds and small trees.

A massive chimney still stood at one end, reaching toward the sky like a monument to a vanished world.

Sarah walked the perimeter of the foundation, trying to imagine what the house had looked like in its prime, probably a typical low country plantation house with wide porches and tall windows designed to catch the breeze.

But it was not the main house that had brought her here.

She scanned the clearing, looking for any other structures.

At first, she saw nothing but trees and undergrowth.

Then, at the far edge of the clearing, partially hidden by a massive live oak, she noticed something.

A small building, its weathered wood nearly the same color as the surrounding forest.

Sarah approached carefully, her heart pounding.

The structure was a cottage much smaller than the main house would have been, perhaps 15 ft square.

The roof had partially collapsed on one side, but the walls were still standing, and miraculously the door remained hanging a skew on rusted hinges.

She pulled out her flashlight.

The interior would be dark, even in daylight, and stepped inside.

The single room was empty of furniture, anything that had once been there long since rotted away or carried off by scavengers.

But the walls told a story that made Sarah’s throat tighten with emotion.

Someone had scratched marks into the plaster.

Hundreds of tiny lines grouped in sets of five.

A prisoner’s calendar counting days, measuring time in a place where time must have felt endless.

Sarah moved her flashlight slowly across the walls, counting.

There were at least 2,000 marks, more than 5 years of days counted and recorded.

In the corner, bolted into the floor with iron that had rusted but not broken, was a metal ring, the kind used to secure a chain.

Sarah spent two hours documenting every detail of the cottage with her camera and notebook.

She photographed the tally marks on the walls from multiple angles, measured the dimensions of the room, documented the metal ring in the floor, and another she found attached to the wall near where a bed might have been positioned.

The evidence was damning.

This had been a prison, however.

It might have been disguised as servants quarters.

As she was preparing to leave, something glinted in the dirt near the doorway.

Sarah knelt and brushed away the accumulated soil and debris.

It was a button, tarnished, but still intact, an ornate button covered in what looked like mother of pearl, the kind used on expensive clothing.

She bagged it carefully in a plastic evidence bag she had brought, then noticed something else partially buried nearby.

A piece of paper wedged between two floorboards, protected from complete decay by its position.

Sarah carefully extracted it with tweezers.

It was fragile, water damaged.

The ink faded to a barely visible brown, but she could make out a few words written in careful, educated script.

My name is Catherine, born free in Richmond, Virginia, 18 years old when they brought me here under false pretenses.

This is my testimony should anyone ever find it.

The rest was too damaged to decipher, but these few fragments were enough to confirm what Sarah had suspected.

Catherine had not come to Charleston willingly.

She had been tricked, kidnapped, or coerced, brought here under the promise of legitimate employment and then imprisoned.

Sarah sat back on her heels, overwhelmed by the weight of what she had discovered.

This was not just a historical curiosity.

It was evidence of a serious crime.

Catherine had been held here illegally years after the 13th Amendment had abolished slavery.

And she had been desperate enough to try to leave a record to scratch marks on walls and hide testimony between floorboards, hoping that someday someone would find it and tell her story.

She spent another 30 minutes searching the cottage and the immediate surrounding area.

She found more buttons, all expensive and decorative, perhaps from the silk dress in the photograph.

She found the rusted remains of what might have been a small cooking pot, a broken comb with delicate teeth, and several pieces of broken china that suggested someone had been living here with at least some material comforts, even if they were a prisoner.

As the afternoon light began to fade, casting long shadows across the clearing, Sarah carefully packed all the evidence she had collected and made her way back to her car.

Her mind was racing with questions.

How long had Catherine been held here? What had happened to her eventually? And most disturbing of all, had she been the only one? That night, back in her Charleston apartment, Sarah could not eat or sleep.

She sat at her kitchen table with the photograph of Catherine, looking into those carefully composed eyes and made a decision.

This story needed to be told completely and accurately, no matter what obstacle she encountered.

Catherine deserve that much.

The next morning, Sarah called her director at the museum, James Morrison.

James, I need to show you something.

It’s urgent, and it’s going to require some difficult decisions about how we proceed.

An hour later, James sat across from her in her office, staring at the photograph with an expression that mixed horror and fascination.

Sarah had laid out everything she had found.

The photograph with its inscription, the evidence from Edestto Island, the fragment of Catherine’s testimony.

Good God, James said quietly.

This is evidence of a felony.

Even if everyone involved is long dead, this is, he paused, searching for words.

Sarah, this changes our understanding of postwar Charleston.

We knew that black people faced violence, discrimination, economic exploitation, but this keeping someone in actual bondage decades after emancipation, this is on another level entirely.

I know, and I need to find out more.

There are sealed papers at the South Carolina Historical Society.

Whitmore family documents that were restricted by Margaret Whitmore’s will.

They’re not supposed to be opened until 50 years after her death, but I think they might contain information about Catherine.

James leaned back in his chair, considering a court order to open sealed documents early would require extraordinary justification.

“You would need to prove that the public interest in accessing them outweighs the deceased’s wishes.

” “I think what I found qualifies as extraordinary,” Sarah said firmly.

Sarah’s initial petition to open the Whitmore papers was denied.

“The probate judge ruled that while her findings were historically significant, they did not constitute the kind of immediate threat to public safety or welfare that would justify breaking the terms of Margaret Whitmore’s will.

” Sarah was not deterred.

If legal channels would not work, she needed to find another approach.

She spent weeks researching the Whitmore family genealogy, tracing descendants through multiple generations.

Margaret Whitmore had never married and had no direct descendants, but her siblings had children who had scattered across the country.

After exhaustive research, Sarah found David Whitmore, a great nephew living in Atlanta.

She called him nervously, unsure how a descendant would react to learning that his ancestors might have committed such crimes.

Mr.

Whitmore, my name is Dr.

Sarah Bennett.

I’m a curator at the Charleston Museum of History, and I’ve discovered some documents related to your family history that I believe you should see.

They concern events that took place in the 1880s.

There was a pause on the other end of the line.

What kind of events? I would prefer to discuss this in person if you’re willing to meet.

What I found raises some very serious questions about your family’s past.

David Whitmore arrived in Charleston 2 days later.

He was in his early 50s, a civil rights attorney with kind eyes and a careful manner of speaking.

When Sarah showed him the photograph of Catherine, his reaction was immediate and visceral.

His face went pale and he had to sit down.

They kept her as a slave, he said quietly.

After it was illegal after the war.

Jesus Christ.

I believe so.

Yes, and I think there may have been others, but I need access to your family sealed papers to understand the full extent of what happened.

David stared at the photograph for a long time, his expression cycling through shock, anger, and finally a kind of weary sadness.

I need to tell you something, Dr.

Bennett.

I’ve always known there was something dark in my family’s history.

My grandmother, Margaret’s younger sister, moved to Atlanta in the 1950s and completely cut off contact with the Charleston Whitmore.

When I was a teenager, I asked her why.

She told me that some families have secrets so terrible that the only honorable thing to do is walk away and never speak of them again.

“But walking away doesn’t erase what happened,” Sarah said gently.

“Catherine was a real person.

She deserves to have her story told.

” David nodded slowly.

What do you need from me? Petition the court as a family member to open the sealed papers.

With your standing and your willingness to confront this history, the judge is more likely to approve access.

David’s petition, combined with his testimony about his family’s history of silence around their Charleston ancestors, changed the calculation.

Three weeks later, the judge ruled that the papers could be opened for purposes of historical research with the condition that any findings would be reviewed before public dissemination to ensure accuracy and context.

Sarah and Dr.

Marcus Webb, a professor at the College of Charleston, whom she had brought in as a consultant, met at the South Carolina Historical Society on a gray Tuesday morning.

The archivist, Helen Rodriguez, brought out three archival boxes that had been sealed for nearly 40 years.

I’ll be honest with you both, Helen said as she placed the boxes on the research table.

I’ve been curious about these since they were sealed in 1985.

Part of me is glad they’re finally being opened.

Part of me is afraid of what you’re going to find.

Sarah pulled on white cotton gloves and opened the first box.

Inside were letters, business ledgers, household accounts, and personal documents spanning from 1875 to 1920.

She began sorting through them methodically while Marcus started on the second box.

They worked in concentrated silence for nearly an hour.

The only sounds the careful rustling of old paper and the scratch of pencils as they took notes.

Then Marcus made a sound, something between a gasp and a groan of dismay.

Sarah, you need to see this right now.

He handed her a leatherbound journal.

The name embossed on the cover in fading gold letters read Ellanar Whitmore.

Sarah opened Elellanar Whitmore’s journal with trembling hands.

The first entry was dated January 1st, 1875.

Written in neat, feminine script that spoke of New Year’s resolutions and hopes for the coming year.

The early entries were mundane.

Social calls, household management, concerns about the children’s education.

But as Sarah turned the pages, moving forward through the years, the tone began to change.

March 15th, 1881.

Richard has brought another girl from Virginia.

Her name is Catherine, and she is quite beautiful, which I suspect is precisely why he chose her.

He claims she came willingly, seeking employment as a lady’s maid, but I saw the confusion and fear in her eyes when she arrived yesterday.

She’s 18 years old, the same age our Margaret was when she made her debut into society.

The contrast between their futures could not be more stark or more unjust.

War.

Sarah’s heart pounded as she read.

Ellaner had known from the very beginning.

She had witnessed Catherine’s arrival and recognized immediately that something was wrong.

April 3rd, 1881.

Catherine has been at Magnolia Hall for 3 weeks now.

Richard visits the island every Friday, returning to Charleston on Monday morning.

He tells our friends and business associates that he is overseeing improvements to the property, modernizing the old plantation buildings.

No one questions this explanation.

No one questions anything Richard Whitmore does.

He is too wealthy, too well-connected, too respected in Charleston society.

I went to Magnolia Hall yesterday without informing Richard.

I told him I was visiting my sister in Bowford.

Instead, I took the ferry to Edesto and hired a carriage to take me to our property.

I found Catherine living in the cottage behind where the slave quarters once stood.

Richard has furnished it comfortably enough.

There’s a proper bed, a small table and chairs, even some books, but there is a lock on the outside of the door, and Catherine showed me the band around her wrist, connected to a chain just long enough to allow her to move about the cottage, but not to reach the door.

Sarah had to pause, her vision blurring with tears.

She looked up at Marcus, who was reading over her shoulder, his expression grim.

“Keep reading,” he said quietly.

April 5th, 1881.

Catherine told me her story.

She was working as a seamstress in Richmond, living with her mother and saving money to open her own dressmaking shop.

A man approached her well-dressed, claiming to represent a wealthy Charleston family, seeking a lady’s maid.

“The position paid extraordinarily well,” he said, and included room and board.

Catherine was suspicious, but the man showed her letters of reference that appeared legitimate.

Her mother encouraged her to accept.

The money would allow them to open the shop much sooner.

When Catherine arrived in Charleston, Richard met her at the train station, but instead of taking her to our meeting street house, he brought her directly to Edestto Island.

He told her that his wife preferred their maid to live on the island property, where she would have her own cottage and more pleasant surroundings than the cramped servants quarters in the city house.

Catherine thought this odd, but had no reason yet to suspect the truth.

It was not until the first night, when Richard locked the door from the outside, and she discovered the restraint attached to the wall, that she understood she had been deceived.

She tried to run the next morning, but Richard caught her on the road.

He told her that if she tried to escape again or told anyone what was happening, he would have her arrested as a thief.

He said he would claim she had stolen jewelry from our Charleston house and that no court would believe the word of a black woman against a white man of his standing.

He was right, of course, no one would believe her.

Sarah set the journal down, needing a moment to compose herself.

The calculated cruelty of Richard Whitmore’s plan was breathtaking.

He had not just kidnapped Catherine, he had created a system that made escape or rescue nearly impossible.

Sarah continued reading Elellanar’s journal, each entry revealing more about the psychological prison that had held both Catherine and Elellanar herself, though in vastly different ways.

May 12th, 1881.

I have been visiting Catherine weekly, always on days when Richard is occupied with business in Charleston.

I bring her books.

She is remarkably intelligent and has taught herself to read with only minimal instruction from me.

I bring her art supplies, better food than the simple provisions Richard leaves for her.

I tell myself, “These gestures matter, that I am helping.

But I know the truth.

I merely salving my own conscience while doing nothing to actually free her.

” Today, Catherine asked me directly, “Why don’t you help me leave?” I had no answer that did not reveal me as a coward.

I told her that Richard controls all our money, that I have no independent means, that if I openly defied him, he might institutionalize me or take the children away.

All of this is true, but it is also true that I’m more afraid of losing my comfortable life than I am committed to doing what is right.

Marcus looked up from the second box of documents he was examining.

Sarah, there are financial records here.

Richard was paying someone in Richmond, a man named Thomas Carver regular sums of money throughout the 1880s.

The ledger entries just say commission, but the amounts are significant.

$200 at a time, equivalent to maybe $5,000 today.

He was paying someone to find women for him,” Sarah said, her voice flat with horror.

“This wasn’t just about Catherine.

It was systematic.

” She turned back to the journal, skipping ahead several months.

November 8th, 1881.

I have discovered Richard’s pattern.

Every year or two, a new girl arrives from Virginia or North Carolina.

Always under the same false pretenses of employment, they are always young, always beautiful, always from circumstances desperate enough that the promise of good wages overcomes their natural caution.

Richard keeps them at Magnolia Hall for a period of time.

I do not know exactly how long, as he does not discuss this matter with me, and then they disappear.

I do not know where they go or what happens to them.

I am too frightened to ask.

Catherine has been at the island for 8 months now.

She has not disappeared like the others.

I think this is because she is the most beautiful of all the girls Richard has brought, and because she has spirit.

She argues with him, challenges him, refuses to be broken.

He seems to find this entertaining.

I find it terrifying.

What will he do when he finally tires of her? Sarah felt sick.

The journal painted a picture not just of one woman held captive, but of multiple women trafficked through Richard Whitmore’s system over years, perhaps decades.

December 25th, 1881, Christmas Day, and I’m consumed with guilt.

Our children opened their presents this morning.

Expensive toys, fine clothes, books imported from Europe.

We attended services at St.

Michael’s Church, where Richard is a respected member and generous contributor.

This afternoon, we will host dinner for Charleston’s finest families.

Everyone will compliment my table settings and menu.

No one will know that 20 m away, a young woman spends this day locked in a cottage alone.

Her family believing she’s employed in a respectable household.

I wrapped a package for Catherine, a warm shaw, some sweets, a book of poetry.

I will take it to her tomorrow when Richard is occupied with his business associates.

She will thank me politely, and I will see the contempt behind her eyes.

She knows I am complicit in her captivity.

My small kindnesses do not absolve me.

The journal entries continued through 1882 and into 1883.

Ellaner documented her visits to Catherine, their conversations, Catherine’s slow acceptance of her situation.

But she also documented something else, a growing determination.

March 7th, 1883.

I have made a decision.

I cannot free Catherine.

Not yet.

Not without a plan that will protect her from Richard’s revenge.

But I can document what is happening.

I can create a record that will survive even if we do not.

Someday someone will need to know the truth about Richard Whitmore and what he has done.

Someday justice may be possible even if it is not possible now.

Sarah realized what she was holding.

Ellaner’s journal was not just a diary.

It was evidence deliberately preserved for future discovery.

As Sarah continued through Ellanar’s journal, she found the entry that explained the photograph, the elegant portrait that had started her entire investigation.

June 2nd, 1889.

eight years.

Catherine has been at Magnolia Hall for eight years now, and she’s still there.

Unlike the other girls Richard brought before her, Catherine has not disappeared.

I think this is partly because she has proven useful to him in ways beyond what he originally intended.

She’s educated, articulate, and he has discovered he can use her as a translator of sorts.

He brings her business documents written in French, which he reads fluently, having learned from her mother, who came from Louisiana.

But I also believe he keeps her because she’s never fully submitted to him.

She maintains a dignity that fascinates and frustrates him in equal measure.

Yesterday, Richard did something extraordinary and disturbing.

He took Catherine to Charleston to William Harper’s photography studio on King Street.

He had her dressed in one of the gowns he purchased for her, an expensive silk dress with pearl buttons, the kind of dress any society lady would be proud to wear.

He had her hair styled fashionably.

To anyone who saw them, they must have appeared as a gentleman escorting a well-dressed companion to sit for a portrait.

But I know the truth because Richard told me, laughing as he did so, he had the photographer attach a decorative chain to the restraint Catherine always wears on her wrist.

In the photograph, it appears to be merely an unusual piece of jewelry.

Only someone looking very carefully would recognize it for what it actually is.

A shackle elegant enough to be overlooked, but present nonetheless.

Oh, when I asked Richard why he would do such a thing, why he would document his crime so explicitly, he said, “Because I can.

because she is mine and I can display my possession however I choose.

And because no one will ever question a photograph of a well-dressed colored woman, they will assume she is a servant who has been treated generously, allowed to dress above her station for portrait, no one will look closely enough to see the truth.

He is right.

Of course, that is the most sickening part.

He can flaunt his crime openly because our society is so steeped in assumptions about race and class that no one will see what is directly before their eyes.

Sarah sat back, overwhelmed.

The photograph was not just documentation.

It was a deliberate act of arrogance.

Richard Whitmore’s way of demonstrating his complete power over Catherine and his confidence that society would never hold him accountable.

But Ellaner’s next entry revealed something Richard had not anticipated.

June 15th, 1889.

I went to Harper’s studio and convinced him to make me additional copies of Catherine’s portrait.

It cost me most of my personal jewelry to pay him.

Richard monitors all monetary transactions, but I had to have proof.

I told Mr.

Harper that I was concerned the original might be lost in a fire or other disaster, and I wanted copies preserved for posterity.

He thought this odd but accepted my money and my explanation.

I have hidden one copy in the back of my wardrobe behind the false panel my father installed years ago when he built this house.

I have given another to my sister Harriet in Philadelphia with instructions to keep it safe and sealed until after my death.

The third I will keep with this journal.

Richard does not know about the copies.

He has the original, which he keeps in his private study, occasionally taking it out to look at, I assume, as one might admire, a particularly fine piece of art one owns.

Someday these copies will serve as evidence.

Someday, when all of us are gone, and the social consequences no longer matter, someone will find them, and understand what Richard did.

I cannot save Catherine now.

I am too weak, too compromised by my own privilege and fear.

But I can ensure that her story does not die with her.

Marcus had been reading over Sarah’s shoulder.

She knew the photographs would survive.

She was deliberately creating evidence for the future.

And she preserved her journal the same way, Sarah said, gesturing to the boxes around them.

These papers were sealed with instructions.

They not be opened for 50 years after Margaret Whitmore’s death.

Ellaner couldn’t tell the truth while it might still hurt her children or grandchildren.

But she made sure the truth would eventually be told.

They continued reading, moving through 1890, 1891, 1892.

Elellanar’s visits to Catherine continued, as did her documentation of what she witnessed.

The entries grew darker as Elellanar’s health began to fail.

She mentioned frequent headaches, difficulty sleeping, a persistent sense of guilt that seemed to be physically wearing her down.

Then, in the spring of 1892, everything changed.

April 3rd, 1892.

Catherine is gone.

Not disappeared in the way the other girls disappeared.

She’s escaped.

And I helped her do it.

Sarah’s heart leapt as she read Elellanar’s words.

She turned the pages quickly, hungry for the details.

For weeks now, I have been planning.

I could not bear it any longer.

The weekly visits where I brought small comforts while doing nothing to address the fundamental horror of Catherine’s situation.

I contacted my sister Harriet in Philadelphia.

Harriet has connections with the Quaker community there.

People who once operated the Underground Railroad and who still help those fleeing impossible situations.

They agreed to shelter Catherine if I could get her to Philadelphia.

The challenge was getting her off Edesto Island and out of South Carolina.

Richard visits the island every Friday and checks that Catherine is still secured in the cottage.

If she disappeared between one of his visits and the next, he would have several days to track her down before she could get far.

But if she disappeared immediately after one of his visits, we might have nearly a week before he discovered her absence.

Last Friday, I watched Richard return from Adisto Island.

He was in good spirits, joking with the children at dinner.

On Saturday morning, I told him I was feeling ill and would spend the day resting in my room.

Instead, I took the ferry to Edestto.

I brought with me a set of tools I had purchased secretly.

A small file, pliers, an iron cutter I bought from a hardware merchant by claiming I needed it for garden work.

When I reached the cottage, Catherine was astonished to see me on a day when I never usually visited.

I showed her the tools and said simply, “Today we end this.

” It took us 3 hours to cut through the restraint on her wrist.

The metal was harder than I anticipated, and both our hands were blistered by the time we finished.

When the shackle finally fell away, Catherine wept, the first time I had ever seen her cry in all the years I had known her.

Sarah found herself crying as she read, imagining that moment of liberation after 11 years of captivity.

I had brought a carpet bag with clothing suitable for travel, simple, modest garments that would not attract attention.

I had money, $300, I had saved secretly over the past year by claiming various household expenses that I never actually incurred.

I had a train ticket from Charleston to Philadelphia, purchased under a false name, and I had a letter for Harriet explaining who Catherine was and what she had endured.

We took the ferry back to Charleston together.

Anyone who saw us would have assumed I was traveling with my maid.

At the train station, I gave Catherine the bag, the money, and the letter.

I told her to trust no one until she reached my sister’s house in Philadelphia.

I gave her Harriet’s address, which I had made her memorize.

As the train pulled away, I stood on the platform and watched it disappear into the distance.

I felt something I had not felt in years, a sense that I had finally done something right, something that mattered, something that partially redeemed my long complicity and evil.

The next entry was dated 3 days later, April 6th, 1892.

Richard discovered Catherine’s absence yesterday.

His rage was terrifying.

He smashed furniture in his study, screamed at the servants, threatened to have the police search every corner of Charleston.

Then he came to me and asked directly, “Did you help her escape?” I looked him in the eye and said yes.

I told him I had freed Catherine and helped her reach Philadelphia where she was now under the protection of people who would not allow her to be taken again.

I told him that if he attempted to pursue her or have her arrested on false charges, I would go to the newspapers with the full story of what he had done.

I would show them the photographs, the financial records, all of it.

He struck me.

It was the first time in our 23 years of marriage that he had raised a hand to me.

I did not care.

I felt nothing but a cold satisfaction that I had finally taken something from him that he could not get back.

Richard has not spoken to me since.

We live in the same house, but as strangers, I do not care about that either.

Catherine is free.

That is all that matters now.

Sarah carefully turned to the final entries in the journal, which were written in a shaker hand.

Ellaner’s health was clearly declining.

June 1st, 1892.

I received a letter from Harriet today.

Catherine arrived safely in Philadelphia and is staying with Quaker friends.

She is learning a trade, dressmaking, the work she was doing before Richard took her.

Harriet says Catherine has nightmares and finds it difficult to trust anyone, which is understandable after 11 years of captivity.

But she is free and she is safe, and that is more than I dared hope for.

The last entry was dated December 30th, 1892.

I am dying.

The doctor says it is a cancer of the stomach, and I have perhaps a few months remaining.

I’m not afraid of death.

I’m only afraid that I waited too long to do what was right.

11 years.

Katherine lost 11 years of her life because I lacked the courage to act sooner.

That sin will follow me to my grave.

But at least I can die knowing that she is free now, that her future is her own.

I have left instructions with my sister that this journal and the photographs should be sealed and preserved.

Someday someone will need to know the truth.

May that truth matter to them as it has mattered to me.

Sarah closed the journal gently and sat in silence for several minutes.

Marcus placed a hand on her shoulder.

Ellaner died in April 1893,” he said quietly, having looked up the records on his laptop.

“She was 48 years old.

” “She helped free Catherine,” Sarah said.

“In the end, she finally did something.

” “But 11 years too late,” Marcus replied.

“1 years of Catherine’s life that can never be recovered.

” Sarah nodded, understanding the complexity of Elellanar’s legacy.

She had been both complicit and courageous, both coward and hero.

She represented something profoundly human.

The capacity to do wrong for a long time before finally choosing to do right.

The discovery of Ellaner’s journal fundamentally changed Sarah’s investigation.

Now she had not just a photograph, but a complete documented history of Catherine’s captivity and eventual escape.

But one crucial question remained.

What had happened to Catherine after she reached Philadelphia? With Marcus’ help, Sarah began searching Pennsylvania records.

They found her quickly.

Catherine Freeman, the surname she had chosen for herself, a declaration of her new status.

She appeared in Philadelphia City directories starting in 1893, listed as a dress maker with a shop on South Street.

Census records showed her living at the same address for decades.

In 1900, she was listed as a 37-year-old dress maker, living alone.

By 1910, she had taken in two apprentices, young black women learning the trade.

In 1920, she was 57 and still working, now employing five people in her shop.

Sarah found newspaper advertisements for Katherine’s business in the Philadelphia Tribune, one of the city’s black newspapers.

Katherine Freeman.

Fine dress making and alterations.

Reasonable rates, work guaranteed.

The advertisements appeared regularly through the 1920s.

But what moved Sarah most was an article she found in a 1918 edition of the Tribune.

It was a profile of successful black business women in Philadelphia, and Katherine was among those featured.

The article was brief but revealing.

Mrs.

Katherine Freeman has operated her dressmaking establishment on South Street for 25 years.

When asked about her success, Mrs.

Freeman said, “I lost many years when I was young to circumstances beyond my control.

When I finally gained my freedom, I vowed that every day afterward would be lived on my own terms.

This shop is mine.

The work is mine.

The future is mine.

That is success.

” The article did not specify what those circumstances beyond her control had been.

But Sarah understood.

Catherine had survived, built a life, and found a way to thrive despite everything that had been taken from her.

Sarah traced Catherine’s life through to its end.

She died in 1932 at age 69, having run her dressmaking shop for nearly 40 years.

Her obituary in the Tribune described her as a beloved member of the community who employed and trained dozens of young women in a respected trade.

With David Whitmore’s permission and cooperation, Sarah prepared an exhibition for the Charleston Museum.

She titled it simply Catherine, a story of captivity and courage.

The exhibition opened on a warm October evening.

The centerpiece was the photograph, the elegant portrait that had started everything, now displayed with full context.

Beside it was the complete story.

Elellaner’s journal entries, the evidence from Magnolia Hall, documentation of Catherine’s life in Philadelphia, and a careful historical analysis of how illegal bondage of black people persisted long after the 13th Amendment.

David Whitmore spoke at the opening.

“This is my family’s history,” he said to the assembled crowd.

I could choose to hide from it, to pretend that my ancestors were better than they were.

But Catherine deserves more than that.

She deserves to be remembered as a full human being, as someone who survived unspeakable cruelty and still built a life of meaning and dignity.

And she deserves to have her story serve as a reminder that injustice can hide in plain sight when we choose not to look closely enough.

The exhibition drew thousands of visitors over its three-month run.

School groups came to learn about a period of history not often discussed.

Historians praised Sarah’s research.

The photograph of Catherine was reproduced in textbooks and scholarly articles.

But for Sarah, the most meaningful moment came on a quiet Tuesday afternoon.

A woman in her 70s approached her at the exhibition.

My grandmother was one of Catherine’s apprentices in Philadelphia.

She said, “She used to tell me stories about Miss Freeman, how she was strict but fair, how she insisted that every young woman who worked for her learn not just to sew, but to manage money and negotiate with customers.

She said Miss Freeman was preparing them not just to work for someone else but to eventually own their own businesses.

“Did your grandmother succeed?” Sarah asked.

The woman smiled.

She owned a tailor shop in North Philadelphia for 40 years.

She taught me to sew and I taught my daughter.

That skill has passed through four generations now, all because Miss Freeman believed that teaching women a trade was a form of freedom.

That evening, Sarah returned to the exhibition after closing time.

She stood alone in front of Catherine’s portrait, looking into those careful, guarded eyes.

But now, knowing the full story, she could see something else in Catherine’s expression.

A determination that had survived 11 years of captivity, a core of selfhood that Richard Witmore had never managed to break.

The restraint on Catherine’s wrist was still visible in the photograph, that elegant shackle that Richard had commissioned to demonstrate his power.

But Sarah understood now that the photograph documented something he had not intended.

It showed a woman who would survive him, who would outlast his cruelty, who would build a legacy that mattered far more than his wealth or social standing ever had.

Sarah pulled out her notebook and wrote the final paragraph for the book she was preparing.

Catherine’s story is not just about the evil that was done to her, though that evil must be named and remembered.

It is also about resilience, about the human capacity to reclaim one’s life, even after years of stolen time.

It is about Elellanar’s late but crucial choice to finally do what was right despite the cost.

and it is about how truth, even when delayed for more than a century, can still serve justice.

This photograph was meant to be a demonstration of power.

Instead, it became evidence, testimony, and ultimately a memorial to a woman who refused to be broken.

Outside, Charleston’s evening streets were busy with tourists and residents enjoying the mild October weather.

The city had changed enormously since 1889, but Sarah knew that traces of the past remained everywhere for those willing to look closely enough.

in old photographs, in sealed journals, and forgotten cottages on barrier islands.

Catherine’s story had been hidden for 135 years.

Now, finally, it was told.

And in the telling, Catherine’s dignity and Elellaner’s delayed courage had found their rightful place in history, not as a shameful secret to be buried, but as a truth that demanded to be remembered.

The photograph remained in the exhibition, no longer hidden, no longer silent.

And Katherine, 11 years a captive, 40 years a successful businesswoman, always and forever a survivor, looked out at those who came to see her.

Her expression a permanent challenge to anyone who might choose to look away from difficult truths.

News

At first, it looked like a photo of two sisters—but then historians noticed their hands

At first, it looked like a photo of two sisters, but then historians noticed their hands. The archive room of…

It was just a portrait of a soldier and his wife—until you notice what he’s holding

It was just a portrait of a soldier and his wife until you notice what he’s holding. The photograph arrived…

It was just a portrait of a mother — but her brooch hides a dark secret

It was just a portrait of a mother and her family, but look more closely at her brooch. The estate…

It was just a seemingly innocent wedding photo from 1920 — but pay attention to the groom’s hand

It was just a seemingly innocent wedding photo from 1920. But pay attention to the groom’s hand. The Maxwell estate…

This 1925 wedding photo has been restored — and what appeared in the mirror shocked historians

This 1925 wedding photo has been restored, and what appeared in the mirror shocked historians. The photograph arrived at the…

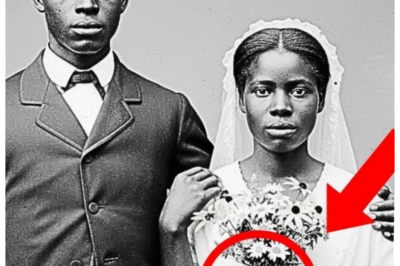

It was just a portrait of newlyweds — until you see what’s in the bride’s hand

It was just a portrait of newlyweds until you see what’s in the bride’s hand. The afternoon light filtered through…

End of content

No more pages to load