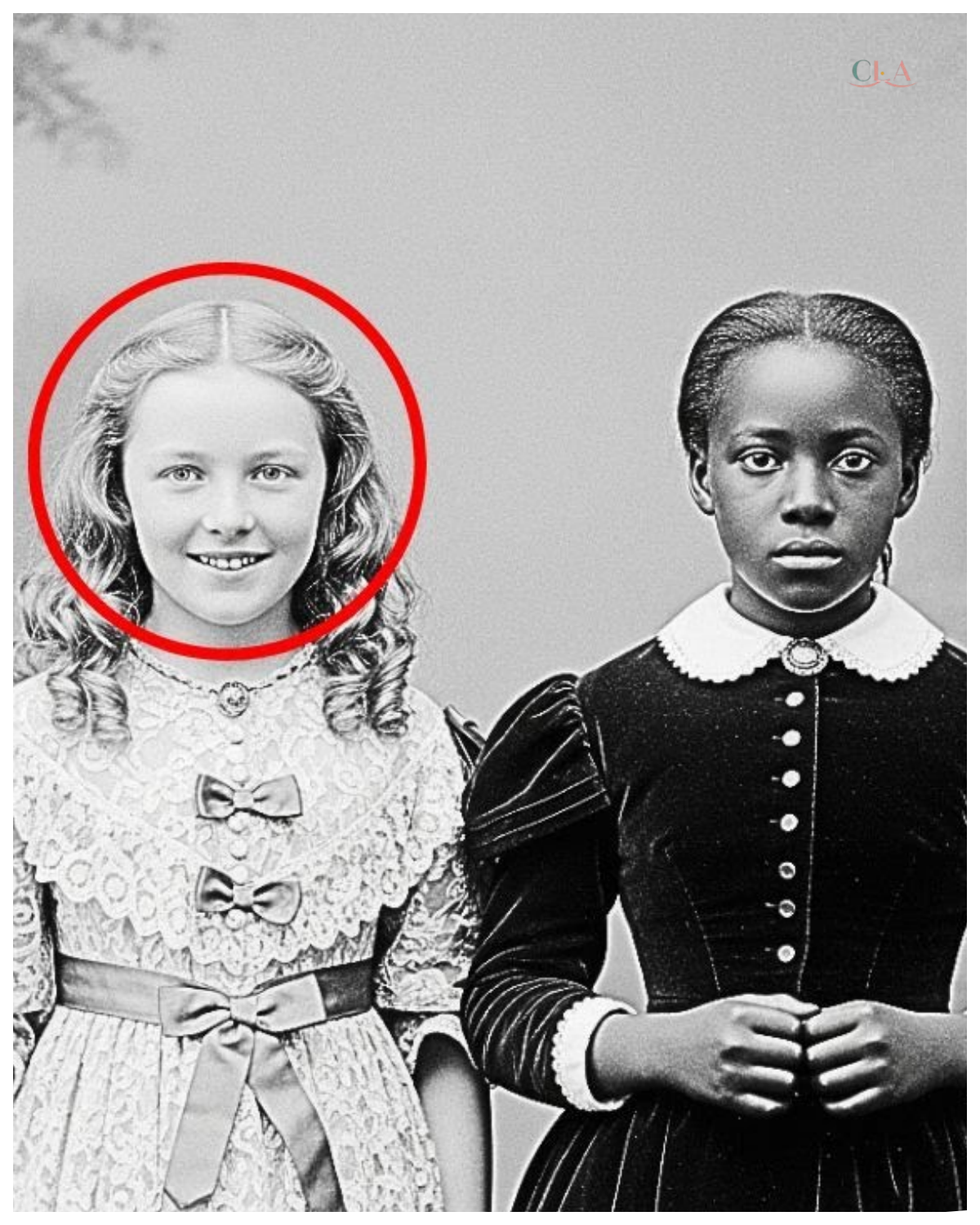

This 1879 photo of two girls seemed adorable until historians uncovered a cruel truth.

The photograph sat in a cardboard box at the Charleston Historical Society for over a century, its edges yellowed and corners softened by time.

Dr.

Rebecca Morrison, a historian specializing in postreonstruction America, had seen thousands of similar images during her career.

But something about this one made her pause that humid August afternoon in 2019.

Two young girls, both appearing around 8 years old, stood side by side in an elaborate photography studio.

The backdrop depicted a painted garden scene popular in the 1870s.

One girl was white with golden ringlets cascading over her shoulders, wearing an ornate white lace dress with ribbon trim.

Beside her stood a black girl in an equally elegant dark velvet dress with white collar detailing.

At first glance, the image seemed to capture childhood friendship across racial lines during a transformative period in American history.

Rebecca leaned closer to her desk lamp, adjusting her magnifying glass.

The white girl displayed a broad, confident smile, her posture relaxed and proprietary.

The black girl’s expression was markedly different.

Stoic, almost frozen, her eyes fixed somewhere beyond the camera lens.

Her hands were clasped tightly in front of her, knuckles prominent even in the faded sepia tone.

“Another staged friendship photo,” Rebecca muttered, making a note in her research journal.

Photography studios in the post civil war south often created such images to project an idealized vision of racial harmony that rarely existed in reality.

She had documented dozens of similar photographs, each telling its own complicated story about the period between slavery’s legal end and the brutal advent of Jim Crow.

But as Rebecca began to set the photograph aside, something caught her attention.

She repositioned her magnifying glass over the black girl’s forearms, visible below her three/arter sleeves.

He even threw the photograph’s age and the limitations of 1879 photographic technology.

She could see what appeared to be marks, linear patterns that seemed deliberately obscured by the careful positioning of the dress sleeves.

Rebecca’s breath caught.

She had seen similar markings in photographs of former enslaved people, scars from restraints and physical punishment, but this photograph was dated 1879, 14 years after the 13th Amendment abolished slavery.

Her hands trembled slightly as she reached for her phone to photograph the image at higher resolution.

Whatever story this picture held, it was far more disturbing than she had initially realized.

The air conditioning hummed in the empty archive room, but Rebecca barely noticed.

She was already mentally preparing for what she knew would be a difficult investigation.

Rebecca spent the next three days in the Charleston Historical Society’s climate controlled archive room, surrounded by leatherbound ledgers, collection cataloges, and historical registers.

The photograph had been donated in 1967 by the estate of Elellanar Whitmore, a descendant of one of Charleston’s prominent families.

Beyond that bare fact, the society’s records offered frustratingly little information.

She carefully documented the photograph using her digital camera, capturing multiple angles under different lighting conditions.

Back in her university office, she uploaded the highresolution images to her computer and used specialized software to enhance the details.

What she discovered made her stomach tighten.

The marks on the black girl’s forearms were unmistakable circular indentations consistent with rope or chain restraints and what appeared to be linear scars from repeated trauma.

These weren’t old scars from slavery times.

They appeared too pronounced, too recent for the photograph’s date.

Rebecca had studied enough primary source images to recognize the difference between old, faded scarring and more recent wounds.

She pulled up the original photograph metadata from the society’s digital catalog.

The notation read, “Portrait of two girls, Charleston Studio, circa 1879.

Photographer JB Whitmore Studio.

” She cross-ferenced this with her database of southern photographers and found that James Bowfort Whitmore operated one of Charleston’s premier photography studios from 1875 to 1892, catering exclusively to wealthy white families.

Rebecca’s colleague, Dr.

Marcus Williams, an expert in African-American genealogy, stopped by her office that evening.

She showed him the enhanced images without preamble.

Marcus studied the screen in silence, his jaw tightening.

Those marks are recent in this photo, he said finally.

“And look at how she’s positioned.

The white girl’s hand is on her shoulder, but not in a friendly way.

See how her fingers are gripping? That’s possessive, controlling.

” “That’s what I thought,” Rebecca replied, her voice strained.

“But Marcus, it’s 1879.

Slavery was abolished in 1865.

These girls weren’t born into slavery.

They would have been born free.

” Marcus turned to her, his expression grim.

You know as well as I do that paper abolition and lived reality were very different things, especially in South Carolina.

Reconstruction was collapsing by 1879.

Federal troops had withdrawn.

The Black Codes might have been technically illegal, but enforcement was another matter entirely.

Rebecca nodded slowly.

She had studied this period extensively, but confronting its cruelty through the eyes of an 8-year-old child felt different than reading statistics and legislative records.

I need to identify these children.

Someone must know who they were.

Start with property records, Marcus suggested.

If what we’re both thinking is true, there might be documentation disguised as something else.

Apprenticeship papers, guardianship contracts, indenture agreements.

White families found ways around the law.

As Marcus left, Rebecca pulled out her notebook and began making a list of archives to search.

Property deeds, court records, church registries, newspaper announcements, personal correspondence, collections.

Somewhere in Charleston’s documented history, these two girls had names, families, and a story that desperately needed to be told.

The Charleston County Courthouse stood as an imposing Greek revival structure on Broad Street.

Its limestone columns weathered by more than a century of coastal humidity and storms.

Rebecca climbed the worn marble steps early Tuesday morning.

Armed with her research credentials and a growing sense of urgency, the civil records department occupied a basement room with inadequate lighting and overwhelming mustustininess.

Filing cabinets lined every wall and cardboard boxes were stacked in seemingly random configurations.

A clerk named Patricia, who appeared to be in her 60s, looked up from her desk with an expression that suggested visitors were a rare and not entirely welcome occurrence.

I’m looking for guardianship and apprenticeship records from the late 1870s, Rebecca explained, showing her university identification, specifically records involving African-American children in white households.

Patricia’s expression shifted from bureaucratic indifference to something resembling recognition.

You’re not the first person to come looking for those particular records.

They’re complicated.

She stood slowly, gesturing for Rebecca to follow her to a far corner of the room.

After reconstruction ended, a lot of white families used apprenticeship laws to essentially reinslave black children.

It was legal on paper.

Orphans and children of indigent parents could be apprenticed to white guardians.

In practice, it meant taking children from their families and forcing them into unpaid labor.

She pulled out a ledger marked apprenticeship contracts 1877 1885 and placed it on a reading table.

These records weren’t kept out of kindness or proper documentation.

They were kept because property has to be tracked, even when you can’t legally call it property anymore.

Rebecca opened the ledger carefully, her historian’s training taking over despite her emotional response.

The pages contained hundreds of entries, names, ages, race indicators, and the names of white guardians.

Each entry represented a childhood stolen, a family separated, a law perverted to maintain the power structures slavery had created.

She photographed each page systematically, knowing she would need to review them more carefully later.

As she worked, Patricia brought over additional documents, court petitions, newspaper advertisements seeking apprentices, and correspondence between families and local authorities.

“You should also check the Whitmore family papers at the South Carolina Historical Society,” Patricia said quietly.

“They donated a collection in the 1960s.

It’s mostly business correspondents and social records, but you might find something there.

” Rebecca worked until the office closed at 5, her laptop filled with hundreds of photographs and her notebook dense with observations.

The apprenticeship records showed that in 1877, a girl named Sarah, age six, race classified as colored, was apprenticed to the Whitmore household.

No last name was given for Sarah, a common practice that stripped enslaved people and their descendants of family identity.

As Rebecca walked back to her car through Charleston’s historic district, she passed antibellum mansions with their manicured gardens and tourist plaques celebrating architectural heritage.

Behind those beautiful facads, she now understood children like Sarah had been trapped in a legal form of slavery that historians had only begun to fully document.

The photograph was no longer just an image of two girls.

It was evidence of a crime that had been hiding in plain sight for 140 years.

The South Carolina Historical Society occupied a stately building on Meeting Street.

Its reading room featuring tall windows that filled the space with natural light.

Rebecca arrived when the doors opened at 9:00, having barely slept the previous night.

Her dreams had been haunted by the face of the black girl in the photograph.

Sarah, she now believed, whose expression suddenly seemed less stoic and more quietly desperate.

The Whitmore family papers filled 12 archival boxes.

Rebecca requested them all and settled in at a corner table with her laptop, camera, and a growing sense of determined anger that she had to consciously channel into methodical research.

The first several boxes contained business correspondents from James Bowfort Whitmore’s photography studio, invoices, letters confirming appointments, notes about equipment purchases.

Box four yielded more personal material, invitations to social events, membership records, and various Charleston organizations, and family letters.

In box 5, Rebecca found what she had been searching for, a letter dated March 1877 written in elegant cursive on expensive stationery from James Whitmore to his sister-in-law in Colombia.

Dear Margaret, I write to inform you that we have successfully secured an apprentice through the county court, a colored girl named Sarah, aged six years.

Catherine is most pleased to have additional help with the household and more importantly a suitable companion for our Emma.

The girl is well behaved and knows her place.

The apprenticeship contract runs until her 18th birthday, which should provide excellent value.

The courts are being most cooperative in these arrangements.

Praise be to God for the restoration of proper order.

Rebecca read the letter three times, photographing it from multiple angles.

The casual cruelty of the language, secured value, knows her place, revealed how completely the Whitmore family had stripped Sarah of her humanity and autonomy.

She was simultaneously a worker and a possession, legally bound to the family that photographed her standing beside their daughter as if they were equals.

The next box contained household ledgers showing expenses for Sarah’s maintenance.

Minimal expenditures for fabric, shoes, and food that stood in stark contrast to the lavish spending on Emma’s clothing and education.

There were no entries for Sarah’s education at all.

A photograph album in box 7 contained multiple images of Emma Whitmore at various ages documenting a privileged childhood filled with elaborate dresses, toys, and family outings.

Tucked near the back was the original photograph Rebecca had found at the Charleston Historical Society.

But this copy included handwritten notation on the back in fading ink.

Emma and her girl Sarah, ages 8, February 1879.

Her girl, not her friend, not Sarah.

The possessive language confirmed what Rebecca had suspected.

Sarah wasn’t photographed as Emma’s companion, but as her property, dressed up for a portrait that would showcase the Whitmore family’s wealth and status.

Rebecca’s hands shook as she photographed the notation.

She needed to find out what happened to Sarah after this photograph was taken, but more urgently, she needed to know who Sarah was before the Whitmore family took her.

Every child deserved to have their full story known, not just the part where they were victimized.

She gathered her materials and approached the reference librarian.

I need to access church records for black congregations in Charleston from the 1870s.

specifically baptismal records and family registers.

The Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church stood on Calhoun Street, its white steeple rising above the surrounding buildings like a beacon.

Founded in 1816, it was one of the oldest black churches in the South and had survived slavery, the Civil War, and the violent backlash against reconstruction.

Its archives held generations of African-American family histories that often existed nowhere else in the documentary record.

Reverend Thomas Hayes, the church archivist, met Rebecca in a small office filled with carefully preserved ledgers and Bibles.

He was a man in his 70s with silver hair and eyes that reflected both warmth and a deep understanding of the painful histories he protected.

“You’re looking for Sarah?” he said simply after Rebecca explained her research.

“No last name given in the apprenticeship contract, age 6 in 1877, bound to the Whitmore family.

” “You know about these cases?” Rebecca asked, surprised.

“I’ve spent 40 years documenting what happened to our children during that period,” Reverend Hayes replied, pulling a thick binder from his shelf.

Between 1865 and 1900, thousands of black children in South Carolina were legally stolen from their families through apprenticeship contracts.

The churches kept their own records because we knew the official history would erase them.

He opened the binder to a handwritten registry.

And we’ve been cross- referencing baptismal records with court documents, trying to identify as many children as possible and connect them back to their families.

Sarah’s case, I believe, is here.

His finger traced down a page to an entry.

Sarah Thomas, baptized April 1871.

Daughter of Grace Thomas and Henry Thomas, both formerly enslaved by the Rutled family.

Father deceased 1875.

Mother remarried 1876 to William Peterson.

Family residence John’s Island.

Rebecca’s throat tightened.

Sarah had a last name, parents, a community.

She wasn’t just a colored girl.

She was Sarah Thomas, whose father had died when she was four and whose mother had remarried, perhaps hoping to provide stability for her child.

What happened to Grace? Rebecca asked.

How did they take Sarah from her? Reverend Hayes pulled out another document, a court petition from 1877.

Uh, Grace was accused of being an unfit mother because she worked in the fields on John’s Island and couldn’t provide what the court called appropriate supervision and education for her daughter.

The Whitmore family, wealthy and well-connected, petitioned to take Sarah as an apprentice.

Grace had no legal representation, no money, and no power.

The court approved the apprenticeship in one hearing.

Could Grace visit her? Did she have any rights at all? The contract stipulated that Grace could visit one Sunday per month at the Whitmore family’s discretion.

In practice, most families made it nearly impossible, setting inconvenient times, moving to homes far from where the parents lived, or simply refusing visits and daring the parents to take legal action they couldn’t afford.

Rebecca looked at the photograph on her laptop screen with new eyes.

Sarah wasn’t just enduring her circumstances in that image.

She was surviving separation from her mother, from her home on Jon’s Island, from everything she knew.

The absence of a smile wasn’t stoicism.

It was grief.

Did Sarah ever return to her family? Rebecca asked, though she feared the answer.

Reverend Hayes shook his head slowly.

That’s what you need to find out.

Some children were eventually reunited with their families when the apprenticeships ended at 18.

Many weren’t.

Some died in servitude.

Some had their contracts extended through various legal manipulations.

Some simply disappeared from the records entirely.

He closed the binder and looked at Rebecca directly.

Sarah deserves to have her full story told.

Not just her suffering, but her family, her identity, her humanity.

That photograph has probably been seen by thousands of people over the years who thought it was charming.

They need to know what they were really looking at.

Rebecca left the church with copies of Sarah’s baptismal record, her parents’ marriage certificate, and documentation of the court case that tore her from her family.

As she drove across the Ashley River toward John’s Island, she felt the weight of responsibility settling on her shoulders.

Sarah’s story had waited 140 years to be told.

She would make sure it was told right.

John’s Island lay southwest of Charleston, connected to the mainland by a series of bridges and causeways that crossed marshland and tidal creeks.

In 1877, when Sarah was taken from her mother, this would have been an arduous journey by boat or wagon.

In 2019, Rebecca drove it in 30 minutes past modern developments and strip malls that had replaced the agricultural landscape where Sarah’s family once lived.

The John’s Island Public Library maintained a local history collection, and Rebecca had made an appointment with Mrs.

Loretta Washington, a community historian whose family had lived on the island for six generations.

Mrs.

Washington, a woman in her 80s with silverframed glasses and hands marked by arthritis, greeted Rebecca warmly.

“Reverend Hayes called to say you were coming.

” “You’re researching Sarah Thomas.

” “You know about her?” Rebecca asked hopefully.

“I know about the Thomas family, and I know what happened to many children during that time.

My own great-grandmother lost two of her siblings to apprenticeship contracts.

” She led Rebecca to a table covered with documents and photographs.

The Thomas family lived in a Freedman’s community near what’s now called Bohickey Road.

After emancipation, formerly enslaved people purchased small plots of land and built homes, farms, and churches.

Grace Thomas’s family, was part of that community.

She spread out a hand-drawn map showing property parcels from the 1870s.

Here’s where the Thomas family land was located.

Henry Thomas, Sarah’s father, purchased 5 acres in 1866.

He was a skilled carpenter and farmer.

When he died in 1875, a farming accident the records show.

Grace was left with their daughter and no means to work the land and care for a young child simultaneously.

That’s when she remarried.

Yes, to William Peterson in 1876.

He was also a freedman trying to establish himself.

But combining two struggling families made them more vulnerable, not less.

The white community saw black land owners as a threat.

They looked for any excuse to disrupt black families and take their children who represented future labor and future competition.

Mrs.

Washington pulled out a bundle of letters tied with fading ribbon.

These were donated by a descendant of the Peterson family.

They’re mostly business correspondents and family news.

But there are three letters from Grace written to her sister between 1877 and 1879 after Sarah was taken.

Rebecca’s hands trembled as she carefully unfolded the first letter dated May 1877.

Written in careful uncertain handwriting.

Dear Sister Ruth, I write to tell you my heart is breaking.

They took my Sarah 3 weeks ago.

The courtman said I couldn’t care for her proper because I work the fields.

But how else am I to earn? Mister Whitmore came with papers and a sheriff and took my baby girl to Charleston.

She cried for me.

I tried to go to her, but they said I would be arrested if I interfered.

They say I can visit one Sunday a month, but it is so far and they choose times when William and I must work.

I don’t know what to do.

Please pray for my child.

The second letter, dated October 1877.

Dear Ruth, I went to see Sarah yesterday.

It took all day to get to Charleston and back.

They made me wait at the kitchen door for an hour before letting me see her for 10 minutes.

Sarah has grown, but she looked so tired.

Ruth.

She didn’t smile.

The white girl, Emma, was there watching us the whole time like Sarah was her doll.

They wouldn’t let me be alone with my own child.

Sarah whispered that she works all day, cleaning, carrying, helping with everything.

She’s 7 years old.

This isn’t freedom, Ruth.

This isn’t what we prayed for.

The third letter, dated August 1879.

Ruth, I haven’t been allowed to see Sarah in 6 months.

Every time William and I try to go, they say it’s not convenient or Emma’s sick or the family is traveling.

I went to a lawyer, but he laughed at me.

said, “Colored folks don’t sue white families in Charleston.

I’m so afraid for my child.

Please keep praying.

It’s all I have left.

” Rebecca looked up, her vision blurred with tears.

Did Grace ever see Sarah again? Mrs.

Washington’s expression was sorrowful.

The letters stop after that.

I don’t know if Grace stopped writing or if her sister stopped keeping the letters or if something happened to prevent further contact.

What I do know is that Grace never got her daughter back.

She died in 1892 at age 46.

The death certificate says pneumonia, but people who knew her said she died of a broken heart.

And Sarah, that’s what you’re trying to find out, isn’t it? Mrs.

Washington said gently.

You need to go back to Charleston, check death records, marriage records, census records, find out if Sarah survived her apprenticeship and what happened when she turned 18.

Rebecca spent the next two weeks searching through every database and archive she could access.

The 1880 census listed Sarah Thomas, age nine, as residing in the Whitmore household with her occupation listed as servant, a euphemism that barely masked the reality of her situation.

She appeared again in the 1890 census, age 19, still living with the family, occupation still listed as servant.

What struck Rebecca was that Sarah’s status hadn’t changed when she turned 18 in 1889.

The apprenticeship contract should have ended, but Sarah remained in the household with no indication she was there by choice or receiving wages.

At the Charleston County Vital Records Office, Rebecca found no marriage record for Sarah Thomas between 1889 and 1900.

No property purchases, no documented children.

In the extensive paper trail that bureaucracy creates, Sarah had effectively disappeared from public record after 1890, even though she had presumably been legally free.

Dr.

Marcus Williams joined Rebecca at her university office one evening, bringing Chinese takeout and his expertise in African-American genealological research.

They spread documents across every available surface, creating timelines and family trees.

Look at this, Marcus said, pointing to a newspaper article from the Charleston Courier dated March 1891.

Fire at the Whitmore residence on King Street.

The article mentions that family and servants escaped without injury, but provides no names for the servants.

The house was badly damaged.

The family relocated to a property on Trad Street while repairs were made.

Why is that significant? Rebecca asked.

Because displaced servants were often the first to leave during family upheavalss.

If Sarah was still essentially enslaved, a crisis like this might have been her opportunity to escape, or it might have made her situation worse if the family was dealing with financial strain from the fire.

Rebecca pulled up property records.

The Tread Street House was smaller, only eight rooms instead of 14.

Fewer servants would have been needed.

They continued searching.

Rebecca checking death records while Marcus examined church records from various black congregations in Charleston.

Hours passed with nothing but frustration until Marcus suddenly stopped.

“Rebecca, look at this.

” He turned his laptop toward her, showing a handwritten entry from the burial register of Magnolia Cemetery.

Dated January 1893.

Sarah Thomas, age 22, colored, entered in the servant section.

Cause of death, pneumonia.

Burial arranged by JB Whitmore family.

Rebecca felt something break inside her chest.

Sarah had died at 22, still in the Whitmore household, four years after her apprenticeship should have ended.

She never married, never had children of her own, never returned to John’s Island or her mother.

She had spent 16 years of her life in servitude from age six to her death and was buried in a section of the cemetery reserved for servants, a final indignity that marked her as property even in death.

“We need to find her grave,” Rebecca said quietly.

“And we need to tell everyone who she was,” Marcus nodded.

The photograph isn’t just evidence of apprenticeship laws anymore.

It’s evidence of a life stolen and a system that continued slavery by another name until it killed her.

They sat in silence for a moment, the weight of Sarah’s story settling over them.

This wasn’t just historical research anymore.

It was an obligation to a child who’d never had the chance to tell her own story, who died without justice or recognition.

Rebecca looked at the photograph again.

Sarah, at 8 years old, standing beside Emma Whitmore, marking visible on her small forearms, her expression containing all the knowledge of what her life had become and would continue to be.

No one who looked at this image should ever again see it as adorable or charming.

“Tomorrow, we go to Magnolia Cemetery,” Rebecca said.

“And then we make sure Sarah’s story is heard.

” Magnolia Cemetery sprawled across nearly 100 acres on the Kooper River.

Established in 1850 as Charleston’s premier burial ground for wealthy white families.

Elaborate monuments marked the graves of Confederate generals, prominent businessmen, and society families who shaped the city’s history.

Rebecca and Marcus walked through manicured paths under ancient oak trees draped with Spanish moss, past marble angels, and imposing family mausoleiums.

The servants section was located in the far northeast corner of the cemetery, marked by simple fieldstones and wooden crosses that time and weather had rendered nearly illegible.

No magnificent monuments here, no family plots with carefully maintained landscaping.

The people buried in this section had served Charleston’s wealthy families in life and remained segregated in death.

Cemetery records indicated that Sarah’s grave was in row 12, plot 37.

They found it near a boundary fence marked only by a small stone with ST1893 carved roughly into its surface.

No full name, no dates of birth, no inscription about beloved daughter or cherished member of the household.

Just initials and a death year.

Rebecca knelt beside the grave, her hands resting on the sunw warmed grass.

Behind her, Marcus remained standing, his hand on her shoulder in silent solidarity.

Sarah Thomas, Rebecca said quietly.

Born 1871 to Grace and Henry Thomas on John’s Island.

taken from her mother at age six.

Died at age 22, never having experienced freedom.

She paused, emotion thickening her voice.

I’m so sorry this happened to you.

I’m sorry no one stopped it.

I’m sorry you died without your mother, without your family, without anyone who truly loved you.

Marcus crouched beside her.

What do you want to do with her story? Rebecca stood slowly, wiping her eyes.

I want to write a comprehensive paper documenting the apprenticeship system in postreonstruction, South Carolina, using Sarah’s case as the centerpiece.

I want that photograph to be the first image people see with Sarah’s full name and story attached.

And I want to work with the cemetery and the historical society to place a proper headstone here with her complete name and dates.

The Whitmore descendants won’t like it,” Marcus said practically.

“They’ll claim you’re damaging their family’s reputation.

” “Their family damaged their own reputation by enslaving a child after slavery was abolished,” Rebecca replied with steel in her voice.

“Sarah deserves recognition, and the hundreds of other children who suffered under this system deserve to have their stories told.

History isn’t just about protecting powerful families legacies.

It’s about revealing the truth, especially the uncomfortable truths we’d rather forget.

Over the next several days, Rebecca worked with Reverend Hayes, Mrs.

Washington, and the Emanuel AM church congregation to raise funds for Sarah’s headstone.

The response was overwhelming.

Descendants of other families who had lost children to apprenticeship contributed.

Community organizations donated, and even some white Charleston families who had learned their own uncomfortable histories participated.

The new headstone was carved from granite, substantial and permanent.

It read Sarah Thomas, 1871 on 1893.

Beloved daughter of Grace and Henry Thomas, taken from her family through unjust apprenticeship.

May her story bring truth and healing.

The dedication ceremony took place on a warm October afternoon in 2019.

More than 200 people attended, historians, community members, descendants of John’s Island Freedman families, and representatives from various Charleston historical organizations.

Reverend Hayes led a prayer.

Mrs.

Washington spoke about the importance of remembering the children who suffered.

Marcus read the letters from Sarah’s mother, Grace.

His voice breaking as he read Grace’s desperate words about her stolen child.

Rebecca stood before the gathering, the photograph displayed on a large screen behind her.

This image has existed for 140 years, she said.

People who saw it probably thought it was charming.

Two little girls dressed up for a portrait.

But now we know the truth.

Sarah Thomas wasn’t Emma Whitmore’s friend.

She was her family’s possession, bound by legal papers that shouldn’t have existed, marked by restraints that shouldn’t have been used.

Separated from a mother who loved her and fought for her, she gestured to the grave marker.

Sarah died young, without experiencing true freedom, without returning to John’s Island, without having children to carry on her story.

But she’s not forgotten anymore.

Her name will be remembered, and the injustice done to her will be taught in schools and universities as a crucial part of American history.

Rebecca’s research paper titled The Hidden Slavery: Child Apprenticeship in Post Reconstruction South Carolina was published in the Journal of Southern History in early 2020.

The photograph of Sarah and Emma served as the cover image, and Sarah’s complete story anchored the broader analysis of how thousands of African-American children were legally reinslaved through apprenticeship contract.

The response was immediate and intense.

News organizations across the country picked up the story.

The Charleston Post and Courier ran a front page feature with the headline, “Photo reveals Charleston’s hidden history of child servitude.

” National media outlets interviewed Rebecca, Reverend Hayes, and Mrs.

Washington.

The photograph went viral on social media, where millions of people saw it and learned what they were actually looking at.

Some responses were supportive and grateful for the historical revelation.

Others were defensive, particularly from descendants of families implicated in the apprenticeship system.

Rebecca received angry emails accusing her of attacking southern heritage and dredging up old grievances.

Some claimed she was exaggerating Sarah’s suffering or that apprenticeship was actually beneficial for black children.

Rebecca responded to these criticisms publicly during an interview with NPR.

This isn’t about attacking anyone’s ancestors.

It’s about telling the truth about American history.

Sarah Thomas was a real child who was taken from her loving mother through legal manipulation and forced to work without pay or freedom until her early death.

That’s not an attack.

That’s documented historical fact.

And if people are more concerned about their ancestors reputations than about a child who suffered, they need to examine their priorities.

The Charleston Historical Society organized a public exhibition titled Portraits and Power: Photography, Race, and Control in Post Reconstruction Charleston.

Sarah’s photograph was the centerpiece displayed alongside the documents Rebecca had uncovered, the apprenticeship contract, Grace’s letters, court records, and the burial registry.

The exhibition included a section on other identified children who suffered under apprenticeship contracts, creating a memorial to lives that had been largely forgotten.

During the exhibition’s opening night, Rebecca stood before the photograph with a reporter from the Washington Post.

What do you want people to understand when they look at this image? The reporter asked.

Rebecca chose her words carefully.

I want people to understand that historical photographs aren’t neutral or objective.

They were created by people with power who controlled how history would be recorded.

The Whitmore family chose to photograph Sarah standing beside their daughter, dressed her in expensive clothing, and created an image that suggested equality and friendship.

But look at Sarah’s face.

Look at her eyes.

She’s telling us the truth if we’re willing to see it.

She’s showing us that she knows exactly what’s happening to her, and she’s surviving despite impossible circumstances.

She paused, her voice softening.

And I want people to know Sarah’s full name and identity.

She wasn’t just a colored girl or Emma’s servant.

She was Sarah Thomas, daughter of Grace and Henry from John’s Island.

She had a family who loved her and fought for her.

She had a community who remembered her.

She matters.

And what happened to her matters.

The exhibition drew record crowds.

Schools began bringing students on field trips to learn about this often overlooked period of American history.

Teachers incorporated Sarah’s story into their curriculum.

The photograph that had sat unnoticed in an archive for over a century became a powerful teaching tool about the gap between legal abolition and actual freedom.

Reverend Hayes told Rebecca during one of the exhibition’s educational sessions.

You’ve given Sarah something she never had in life, a voice and recognition.

That’s a profound gift.

Marcus, standing nearby, added, “And you’ve shown that historical research isn’t just about discovering facts.

It’s about restoring dignity to people who were denied it.

” Rebecca looked at the crowd surrounding Sarah’s photograph.

People of all ages and backgrounds, reading the explanatory text, studying the documents, and truly seeing Sarah for perhaps the first time.

This was why she had become a historian, to uncover truth, challenge comfortable narratives, and ensure that people like Sarah were remembered as full human beings, not footnotes in someone else’s story.

Two years after Rebecca’s research was published, the impact of Sarah’s story continued to resonate.

The apprenticeship system in postreonstruction America became a standard topic in African-American history courses, several other historians began researching similar cases in different southern states, discovering that thousands of children had been legally bound to white families and what amounted to continued enslavement.

In Charleston, the city council passed a resolution formally acknowledging the apprenticeship system and its devastating impact on black families.

They committed funding to identify other children who had been taken and to create permanent memorials recognizing this history.

John’s Island erected a historical marker near where the Thomas family land had been located.

The marker told Grace and Sarah’s story, including Grace’s desperate letters and the years she fought to see her daughter.

Mrs.

Washington, now in her mid 80s, attended the dedication ceremony with tears streaming down her face.

Grace would be so proud.

She said her daughter’s story is finally being told and people are listening.

The Whitmore family descendants had mixed reactions.

Some acknowledged their ancestors role and participated in educational efforts.

Others remained defensive, though their protests had diminished as the historical evidence became widely known and accepted.

Emma Whitmore, the white girl in the photograph, had lived until 1967.

Rebecca discovered that Emma had become a teacher and later a principal in Charleston’s segregated school system, perpetuating the racial hierarchies she had been raised in.

Her obituary made no mention of Sarah or any other servants who had worked in her family’s home.

The silence itself was telling Sarah had been important enough to photograph, but not important enough to acknowledge in the family’s official history.

Rebecca continued her research, identifying 17 other African-American children who had been apprenticed to white Charleston families during the same period.

Each child now had a name, a story, and a place in the historical record.

She worked with community organizations to locate their graves and ensure they were properly marked.

The photograph itself traveled to museums across the country as part of exhibitions on American history, slavery’s legacy, and reconstruction.

Each time people viewed it, they learned Sarah’s name, heard Grace’s words from her letters, and understood that the abolition of slavery had not ended the exploitation and control of black bodies.

It had simply transformed how that exploitation was legalized and maintained.

Rebecca received an email one evening from a woman in California named Jennifer Thomas.

The message began, “I think Sarah might have been my great great great aunt.

” Jennifer had seen the news coverage and recognized the Thomas family name from her own family tree.

Her ancestors had also lived on John’s Island in the 1870s, connected to Sarah’s family through her father, Henry’s siblings.

Rebecca and Jennifer spent months working together, connecting genealological records and family stories.

Jennifer visited Charleston, met with Mrs.

Washington and Reverend Hayes and stood at Sarah’s grave for the first time.

“She has family who knows her now,” Jennifer said, placing flowers on the headstone.

“She’s not alone anymore.

” “The connection gave Rebecca profound satisfaction.

Sarah’s story wasn’t just a historical case study.

It had reconnected a family separated by generations and trauma, giving Sarah’s living descendants a chance to honor her memory and understand her suffering.

On the fifth anniversary of Rebecca’s initial discovery, she returned to the Charleston Historical Society.

The photograph was no longer in a cardboard box in the archive room.

It had been professionally conserved and was now displayed prominently in the main gallery with the full context of Sarah’s story.

Rebecca stood before it one more time, studying Sarah’s face with the knowledge of everything that had been uncovered.

“Thank you for waiting,” she whispered.

“Thank you for leaving evidence in your eyes and your expression that made me look closer.

You made sure your truth could be found.

” Behind her, school children on a field trip gathered around their teacher, who began telling them about Sarah Thomas, her mother, Grace, and the hidden system of child servitude that followed slavery’s legal end.

The children listened with wide eyes, asking questions, expressing outrage at the injustice.

One small girl, about the same age Sarah had been in the photograph, raised her hand.

“Did Sarah ever get to be happy?” she asked.

The teacher paused, choosing her words carefully.

“We don’t know if Sarah had moments of happiness in her life.

What we do know is that many people fought for her.

her mother, Grace, her community, and now historians like Dr.

Morrison.

We’re making sure Sarah is remembered as she deserved to be, as a person with dignity, a family, and a story that matters.

Rebecca smiled through tears.

That was exactly right.

Sarah hadn’t been given justice or freedom in her lifetime, but she had something now that the Whitmore family had tried to deny her recognition as a full human being whose life had value beyond her labor, whose suffering mattered, and whose story would be told honestly for generations to come.

The photograph would remain, but it would never again be seen as adorable or charming.

It would stand as evidence of a painful truth that the end of slavery did not mean the end of injustice, and that freedom written on paper did not guarantee freedom in life.

And it would stand as a memorial to Sarah Thomas, who survived 16 years of servitude with dignity, who maintained her identity even as others tried to erase it, and who finally, more than a century after her death, received the recognition and respect she should have had all along.

News

🌲 IDAHO WOODS HORROR: COUPLE VANISHES DURING SOLO TRIP — TWO YEARS LATER FOUND BURIED UNDER TREE MARKED “X,” SHOCKING AUTHORITIES AND LOCALS ALIKE ⚡ What started as a quiet getaway turned into a terrifying mystery, as search parties scoured mountains and rivers with no trace, until hikers stumbled on a single tree bearing a carved X — and beneath it, a discovery so chilling it left investigators frozen in disbelief 👇

In August 2016, a pair of hikers, Amanda Ray, a biology teacher, and Jack Morris, a civil engineer, went hiking…

⛰️ NIGHTMARE IN THE SUPERSTITIONS: SISTERS VANISH WITHOUT A TRACE — THREE YEARS LATER THEIR BODIES ARE FOUND LOCKED IN BARRELS, SHOCKING AN ENTIRE COMMUNITY 😨 What began as a family hike into Arizona’s notorious mountains turned into a decade-long mystery, until a hiker stumbled upon barrels hidden in a remote canyon, revealing a scene so chilling it left authorities and locals gasping and whispering about the evil that had been hiding in plain sight 👇

In August of 2010, when the heat was so hot that the air above the sand shivered like coals, two…

⚰️ OREGON HORROR: COUPLE VANISHES WITHOUT A TRACE — 8 MONTHS LATER THEY’RE DISCOVERED IN A DOUBLE COFFIN, SHOCKING AN ENTIRE TOWN 🌲 What began as a quiet evening stroll turned into a months-long nightmare of missing posters and frantic searches, until a hiker stumbled upon a hidden grave and police realized the truth was far darker than anyone dared imagine, leaving locals whispering about secrets buried in the woods 👇

On September 12th, 2015, 31-year-old forest engineer Bert Holloway and his 29-year-old fiance, social worker Tessa Morgan, set out on…

🌲 NIGHTMARE IN THE APPALACHIANS: TWO FRIENDS VANISH DURING HIKE — ONE FOUND TRAPPED IN A CAGE, THE OTHER DISAPPEARS WITHOUT A TRACE, LEAVING INVESTIGATORS REELING 🕯️ What started as an ordinary trek through the misty mountains spiraled into terror when search teams stumbled upon one friend locked in a rusted cage, barely alive, while the other had vanished as if the earth had swallowed him, turning quiet trails into a real-life horror story nobody could forget 👇

On May 15th, two friends went on a hike in the picturesque Appalachian Mountains in 2018. They planned a short…

📚 CLASSROOM TO COLD CASE: COLORADO TEACHER VANISHES AFTER SCHOOL — ONE YEAR LATER SHE WALKS INTO A POLICE STATION ALONE WITH A STORY THAT LEFT OFFICERS STUNNED 😨 What started as an ordinary dismissal bell spiraled into candlelight vigils and fading posters, until the station doors creaked open and there she stood like a ghost from last year’s headlines, pale, trembling, and ready to tell a truth so unsettling it froze the entire room 👇

On September 15th, 2017, at 7:00 in the morning, 28-year-old teacher Elena Vance locked the door of her home in…

🌵 DESERT VANISHING ACT: AN ARIZONA GIRL DISAPPEARS INTO THE HEAT HAZE — SEVEN MONTHS LATER SHE SUDDENLY REAPPEARS AT THE MEXICAN BORDER WITH A STORY THAT LEFT AGENTS STUNNED 🚨 What began as an ordinary afternoon spiraled into flyers, helicopters, and sleepless nights, until border officers spotted a lone figure emerging from the dust like a mirage, thinner, quieter, and carrying answers so strange they turned a missing-person case into a full-blown mystery thriller 👇

On November 15th, 2023, 23-year-old Amanda Wilson disappeared in Echo Canyon. And for 7 months, her fate remained a dark…

End of content

No more pages to load