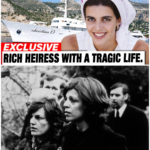

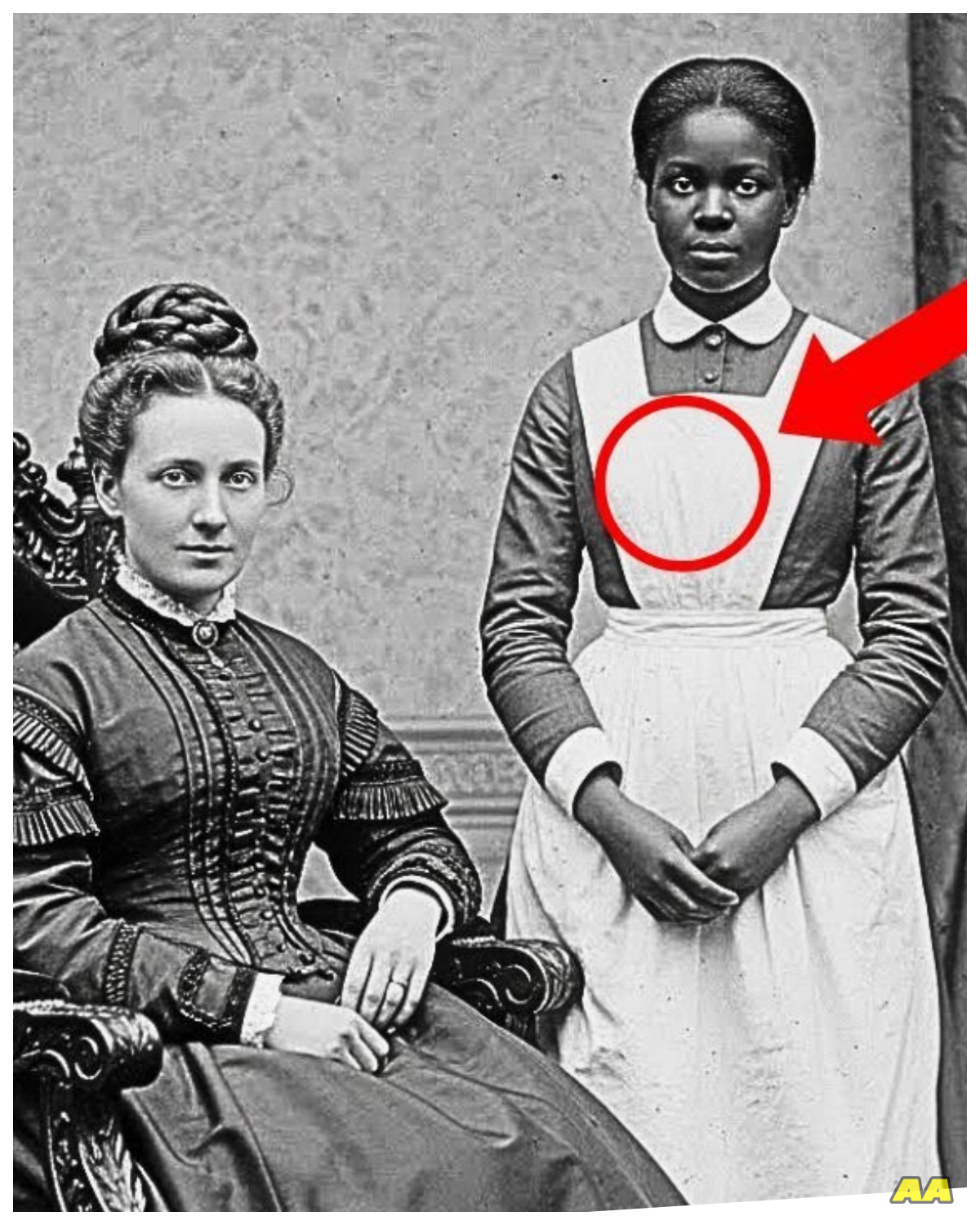

This 1878 portrait appears ordinary until experts zoom in and notice something impossible.

The afternoon sun streamed through the tall windows of the Virginia Historical Textile Archive as Dr.Naomi Carter carefully photographed another Victorian era garment.

It was a Tuesday in October 2024 and she was halfway through digitizing a collection of 19th century clothing and photographs donated by a Richmond estate.

Most items were predictable.

Elaborate ball gowns, men’s formal wear, children’s christening outfits.

But Naomi treated each piece with the reverence it deserved after 20 years as a textile historian.

She reached for the next item in the archival box, a large photograph in a gilded frame, its glass surprisingly intact.

The image showed two women in a photographers’s studio.

A white woman, perhaps in her early 40s, sat regally in an ornate velvet chair, wearing an expensive silk gown with elaborate pleading and lace trim.

Her dark hair was swept up in the fashion of the late 1870s, and her expression was composed, almost stern.

Standing slightly behind, and to her right, was a young black woman, maybe 20 years old, dressed in a simple but well-made servants uniform, a dark dress with a white apron and collar.

Naomi turned the photograph over.

On the back, written in faded ink, was a notation.

Mrs.

Elizabeth Hartwell and household servant, Richmond, Virginia, April 1878.

She set the frame carefully on her workstation and studied the image more closely.

The composition was typical for the era.

Wealthy families often included domestic servants and formal portraits as a display of a status and prosperity.

What was less typical was the quality of the photograph itself.

The clarity was exceptional.

The lighting perfectly balanced, suggesting this had been taken by a skilled and expensive photographer.

But something about the image nagged at her.

Naomi had examined thousands of period photographs, and her trained eye could detect subtle details that others might miss.

She reached for her highresolution digital camera and began photographing the portrait in sections, capturing every detail for closer analysis on her computer.

When she transferred the images and zoomed in on her monitor, her breath caught.

The servant’s uniform, which had appeared simply white in the original viewing, was actually covered in intricate embroidery.

The collar and apron weren’t plain cotton.

They were decorated with elaborate needle work and white thread on white fabric, nearly invisible to the casual observer, but unmistakably present under magnification.

Naomi leaned closer to the screen, her pulse quickening.

The embroidery wasn’t merely decorative.

The patterns were too precise, too geometric, too deliberately arranged.

Along the collar’s edge ran a series of small symbols, stars, diamonds, crosses, and circles, each carefully stitched in a specific sequence.

The apron featured similar patterns with additional elements that looked almost like simplified maps, lines intersecting at angles, small X marks at specific points, and what appeared to be directional indicators.

She had seen coded needle work before.

During the Civil War, some women had embroidered military intelligence into quilts and handkerchiefs.

But this photograph was from 1878, 13 years after the war’s end.

Why would someone encode information into a servant’s uniform? And why document it so carefully in an expensive photograph? Naomi spent the next three days consumed by the photograph.

She created detailed sketches of each visible symbol, measured angles, counted stitches, and documented every pattern.

She cross referenced the image with databases of Victorian embroidery, military codes, and period symbolism.

Nothing matched.

The patterns were unique, or at least unknown to modern scholarship.

On Thursday morning, she decided to consult Dr.

Marcus Webb, a colleague who specialized in African-American history and coded communication during the slavery and reconstruction eras.

She found him in his cluttered office on the museum’s third floor, surrounded by stacks of books and archival boxes.

Marcus looked up from his laptop as she entered, his reading glasses perched on his nose.

“Marcus, I need you to look at something,” she said, placing her laptop on his desk and opening the high resolution scan of the photograph.

“Tell me what you see,” he leaned forward, studying the image carefully.

His expression shifted from casual interest to intense focus.

After a long moment, he sat back in his chair, removing his glasses.

“Where did you find this?” “In the estate collection.

It came with other items.

Nothing particularly remarkable, but look at the embroidery on the servants’s uniform.

Every pattern is deliberate, Marcus.

This is coated.

Marcus stood and moved closer to the screen, zooming in on the collar, then the apron, his jaw tightened.

Naomi, I’ve seen references to something like this before.

Not exactly this, but similar.

There were stories, oral histories passed down in some African-American families about domestic workers who used needle work to encode information, ways to communicate without words, to identify safe houses, to warn of danger.

Most historians dismissed them as folklore because there was never any physical evidence.

Naomi’s heart raced.

But this is evidence.

This might be evidence.

Marcus corrected carefully.

We need to be certain before we make any claims.

But if this is what I think it is, you found something that could change how we understand post-war resistance networks.

He pulled a book from his shelf, flipping through pages until he found what he was looking for.

A collection of oral histories from formerly enslaved people compiled in the 1930s.

One passage highlighted in yellow described special sewing used by domestic workers to carry messages between households.

The descriptions are vague, Marcus said.

But they mention white thread on white fabric patterns that looked decorative but held meaning.

Look at the servant’s collar in your photo.

Those symbols aren’t random decoration.

Naomi looked again at the careful arrangement of stars, crosses, diamonds, and circles.

Her skin prickled with excitement.

We need to find out who these women were.

Marcus nodded slowly, still studying the image.

And we need to understand what message they were preserving.

Because if someone went to this much trouble to document coded needle work in a professional photograph, it wasn’t just about pretty embroidery.

They were creating a permanent record of something important.

The back of the photograph’s mounting board provided their first real lead.

In faded pencil, someone had written, “Mrs.

Elizabeth Hartwell and household servant, Richmond, Virginia, April 1878.

” No first name for the servant, no street address, but it was enough to begin their search.

Naomi and Marcus spent the following week immersed in Richmond’s historical records.

They started with Elizabeth Hartwell since they at least had her name.

Richmond’s Historical Society had extensive records from the post civil war period and Naomi found her quickly in census data and property records.

Elizabeth Hartwell had been born Elizabeth Morrison in 1836 to a prominent Richmond merchant family.

She had married Charles Hartwell, a successful textile importer in 1856.

The couple had two daughters, both of whom died in a diptheria outbreak in 1869.

Charles himself had died in 1875, leaving Elizabeth a childless widow at 39.

On the surface, it was a tragic but unremarkable story for the time.

But as Naomi dug deeper, she found peculiarities.

Elizabeth’s household expenses recorded in ledgers held by the historical society showed unusual patterns.

Large sums were spent on household supplies and charitable contributions with remarkable frequency.

Aounts that seemed excessive even for a wealthy widow maintaining a social position.

More intriguingly, Elizabeth’s name appeared in connection with several progressive causes.

She had donated to schools for black children, supported a women’s literacy program, and was listed as a patron of the first African Baptist church, unusual for a white woman of her social standing in 1870s Richmond.

Marcus, meanwhile, was trying to identify the servant in the photograph.

Without a name, the task was significantly harder.

He started by examining Elizabeth Hartwell’s household records, looking for any black women employed between 1876 and 1880.

He found several names, but one appeared with unusual frequency in the expense ledgers.

a woman listed simply as Clara.

Unlike other servants who appeared for a few months or a year before their names disappeared from the records, Clara’s name appeared consistently from 1876 through 1882.

She was paid more than typical domestic servants, not dramatically more, but noticeably more.

And there were occasional additional payments noted as travel expenses and special services.

A long-term, well-paid servant who traveled, Marcus said, reviewing his notes with Naomi.

That suggests Elizabeth trusted her implicitly.

In the context of the photograph, it suggests something more, a partnership.

They found Clara’s name in one more place.

The membership roles of the First African Baptist Church.

Listed in 1877 was Clara Washington, domestic servant, residing at the Hartwell residence.

Clara Washington, Naomi said softly, looking again at the young woman’s face in the photograph.

Now we have a name.

With both names, they could search more effectively.

Marcus contacted descendants of families who had attended First African Baptist Church in the 1870s.

One woman, Mrs.

Elellanar Patterson, responded immediately.

I know that name, she wrote.

Clara Washington.

My great great-grandmother mentioned her in family stories.

She called her the seamstress who swed freedom.

Mrs.

Elellanar Patterson invited them to her home in Richmond’s Church Hill neighborhood.

She was 92 years old, sharp-minded, and keeper of her family’s history.

Her small house was filled with photographs, documents, and carefully preserved artifacts spanning generations.

She served them sweet tea and settled into her favorite chair, surrounded by the history of her family.

My great great grandmother, Viola, was born in 1870, Ellaner began.

She was too young to remember the Civil War, but she remembered the hard years that followed.

She told stories about women in the community who did dangerous work to help people escape violence, find safer places to live, or reunite with family members who had been separated during slavery.

Did she mention Clara Washington specifically? Marcus asked gently.

She did.

She said Clara worked for a white woman who was good people.

That was how she phrased it.

Viola said Clara could put messages in needle work that only certain people could read.

She said Clara traveled all over Virginia and into North Carolina, supposedly as a lady’s companion, but really she was carrying information and coordinating safe houses.

Elellanar stood slowly and retrieved a small wooden box from a cabinet.

Inside was a handkerchief, yellowed with age, but still intact.

Viola kept this.

She said Clara had given it to her mother during a difficult time.

Look at the corners.

Naomi examined the handkerchief carefully.

In each corner embroidered in white thread were small symbols.

A star, a cross, a diamond, and a circle.

The same symbols that appeared on Clara’s collar in the photograph.

This is extraordinary, Naomi breathed.

This is physical evidence of the coding system.

We can study the stitching techniques, compare the patterns, potentially decode the messages.

There’s more, Ellaner said.

She pulled out a small leather journal.

Its pages brittle with age.

This belonged to Viola’s mother, Sarah.

She wasn’t fully literate.

Many entries are just drawings and simple words, but she kept records.

Look at the entries from 1878.

Marcus carefully turned the pages.

In April 1878, the same month the photograph had been taken, there was a series of entries showing small sketched symbols, some matching those on the handkerchief and in the photograph.

Beside the symbols were brief notes.

Mrs.

H.

house safe.

Clara says, “Road clear north.

Meeting at church tomorrow.

” “This is a log,” Marcus said, his voice filled with awe.

Sarah was documenting messages she received through Clara’s needle work.

She was part of the network.

Ellaner nodded.

Viola said her mother helped at least a dozen families escape violence in the late 1870s and early 1880s.

She said they used the seamstress’s language to coordinate everything, and nobody outside the community ever understood what they were doing.

Naomi looked at the photograph on her tablet, seeing it now with complete clarity.

Clara Washington wasn’t just wearing a uniform.

She was wearing a communication device, all hidden in plain sight as ordinary servants clothing.

And Elizabeth Hartwell had helped her create it, fund it, and document it for posterity.

Naomi and Marcus assembled a small team of experts to decode the embroidery on Clara’s uniform.

They brought in Dr.

Helen Chu, an expert in historical textiles and needle work.

Professor David Armstrong, a cryptographer who specialized in historical codes, and Jennifer Blake, a digital imaging specialist who could capture every thread and stitch in high resolution detail.

They converted one of the museum’s conference rooms into a research hub, covering the walls with enlarged prints of the photograph, and detailed diagrams of each embroidered pattern.

Jennifer’s enhancement work revealed subtleties invisible to the naked eye, the precise angle of each stitch, slight variations in thread thickness, the specific positioning of symbols.

Helen examined the stitching techniques first.

“This is white work embroidery,” she explained, showing them close-ups of the thread patterns.

“It’s a technique where white thread is used on white fabric, creating subtle texture and pattern that’s difficult to see unless you’re looking for it.

It was popular in the Victorian era for decorative purposes, but it also had practical applications.

You could hide messages in plain sight.

” She pointed to the specific stitches used in the symbols.

These are satin stitches, French knots, and chain stitches.

All standard techniques, but the arrangement is anything but standard.

Each symbol is stitched in a very specific way.

The number of threads used, the direction of the stitches, even the tension, all of it varies deliberately.

This isn’t just artistic choice.

It’s encoding additional layers of information.

David Armstrong approached the symbols as a cryptographic system.

He photographed each distinct symbol they had found, cataloged them, and began looking for patterns.

Over two weeks, he identified 37 unique symbols.

some appearing frequently, others only once or twice.

This appears to be a substitution cipher combined with positional encoding, he explained during a team meeting.

Each symbol represents something, a location, a person, a status indicator, but the meaning can change based on where it appears.

A star on the collar means something different than a star on the apron.

He had created a large chart showing his analysis.

The most common symbols seem to indicate safety and danger.

The star, which appears frequently, likely means safe.

The cross might indicate a church or religious ally.

The diamond appears near what look like route indicators, so it might mean pathway or passage.

The circle always appears at intersection points, so it might indicate a meeting place.

Marcus contributed historical context.

He had found references in other documents to specific locations in Richmond and surrounding areas that had been known as safe houses or meeting places for the black community during the 1870s and 1880s.

When he overlaid these known locations onto a map and compared them to the pattern embroidered on Clara’s apron, the correlation was striking.

“Look at this,” he said, projecting both images side by side.

“The First African Baptist Church here in the records and here on the apron, marked with a cross and circle.

The Freeman School here in property records and here on the apron.

Dr.

Pierce’s medical office, known for treating black patients, and here on the apron.

” Naomi counted the marked locations.

There are at least 20 different sites on this piece of embroidery.

Clara was walking around with a comprehensive map of the entire Richmond network.

Tracing Clara Washington’s life proved challenging.

Unlike Elizabeth Hartwell, whose life was documented through property records, and social announcements, Clara’s presence in the historical record was fragmentaryary.

Glimpses in household ledgers, church registries, and census records, but never a complete picture.

Marcus started with the census.

In 1880, Clara Washington was listed as a 24year-old black woman employed as a domestic servant in the Hartwell household.

No parents or siblings were listed, and her birthplace was noted simply as Virginia.

The 1870 census showed no Clara Washington in Richmond, suggesting she had arrived in the city sometime between 1870 and 1876.

She could have been born enslaved, Marcus explained.

Many people born in slavery either didn’t know their exact birth dates or had their records destroyed.

The fact that she appears in Richmond in her late teens suggests she might have migrated there after emancipation, possibly looking for family or work.

He found her name in church records more frequently.

First African Baptist Church noted her membership in 1876, and she appeared in records of various church activities, prayer meetings, charitable committees, and educational programs.

One notation from 1879 listed her as helping to teach needle work to young women in the congregation.

She was training others, Naomi realized, passing on the skills and probably the code itself.

This wasn’t just about her individual work.

She was building capacity within the community.

Professor Armstrong had been researching whether similar coding systems had been used in other locations.

He discovered a collection of letters in the Library of Congress written by abolitionists and civil rights workers in the 1870s and 1880s.

One letter written in 1881 by a Quaker woman in Philadelphia mentioned receiving a visitor from Richmond.

A young colored woman came to a friend’s meeting yesterday.

The letter read, “She brought recommendations from Elizabeth H of Richmond.

The visitor C is most accomplished in needle work and showed us such remarkable pieces, all done in white on white, with symbols I did not fully understand, but which she explained had meaning for her community.

” She spoke of teaching this art to others as a way of preserving their history.

“Clara traveled,” Marcus said excitedly.

She wasn’t just working in Richmond.

She was moving between cities, probably coordinating networks, sharing the coding system, training others.

Naomi found additional evidence supporting this.

Elizabeth Hartwell’s expense ledgers showed regular payments for Clara’s travel expenses from 1877 through 1882.

The amounts and timing suggested trips to Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington, and even as far as Boston.

They tried to trace Clara’s movements through the early 1880s, but the trail became harder to follow.

Her name appeared less frequently in Richmond records after 1882.

Elizabeth’s ledgers showed final payments for Clara’s travel in June 1882 and then no more mentions.

Marcus found a possible answer in the church records.

In October 1882, First African Baptist Church recorded a memorial service for members who have gone north seeking safety.

Among the names was Clara Washington.

Elellanar Patterson’s cousin who lived in Boston had been researching their family tree and discovered something remarkable.

She found a newspaper clipping from the Boston Daily Globe dated April 1883, announcing the opening of the Washington School for Domestic Arts, operated by Miss Clara Washington, formerly of Richmond.

And while Marcus traced Clara’s movements north, Naomi focused on Elizabeth Hartwell’s later years.

After Clara’s departure in 1882, Elizabeth’s household ledgers showed she employed several other servants, but none stayed more than a year or two.

Her charitable donations continued.

She supported black schools, churches, and benevolent societies, but the large, mysterious expenses that had characterized the late 1870s and early 1880s disappeared from her records.

Richmond Society pages mentioned her occasionally through the 1880s, usually in connection with charitable events or church activities.

She was described as a respectable widow devoted to good works, but the tone was often faintly disapproving, as if her particular choices of charitable focus were not quite acceptable in polite society.

Then, in 1889, something changed.

Naomi found a letter in the Virginia Historical Society archives written by a prominent Richmond woman to her sister.

The letter mentioned Elizabeth with barely concealed scandal.

Mrs.

Hartwell has become quite peculiar, my dear.

She dined last week at the home of the Reverend Johnson, the Negro Minister.

Several people saw her entering his home in broad daylight.

She continues to associate with the colored community in ways most inappropriate for a woman of her station.

Naomi found more references in similar sources.

Elizabeth was seen attending services at black churches, hosting meetings in her home with black community leaders, and publicly supporting causes like integrated education and voting rights, positions that were increasingly radical and dangerous in the Jim Crow South of the late 1880s.

In 1891, Elizabeth sold her Richmond house and moved to Philadelphia.

The sale records showed she received a good price, but she sold it to First African Baptist Church, which converted it into a community center and school.

Marcus helped track Elizabeth’s Philadelphia years.

She bought a modest rowhouse in a racially mixed neighborhood and continued her pattern of charitable work and community involvement.

Most significantly, Elizabeth was listed as a financial supporter of the Washington School for Domestic Arts, Clara’s School.

They planned this together, Naomi said.

Clara went north first, established the school, got it running, then Elizabeth followed.

Once Clara had created a situation where they could continue their work with less risk, the team found letters between Elizabeth and various correspondents that confirmed this interpretation.

In one letter from 1893, Elizabeth wrote, “I find the work here most rewarding.

There are so many young women who need the skills that can make them independent and safe.

I am grateful to support their education and to work alongside those who understand the importance of preserving the wisdom that carried us through the darkest times.

Elizabeth Hartwell died in 1903 at the age of 67.

Her obituary was brief, noting her as a widow from Virginia who devoted her later years to charitable work, but her will told a different story.

She left her estate divided between First African Baptist Church in Richmond, the Washington School in Boston, and a scholarship fund for black women seeking teacher training.

Most intriguingly, she left a small legacy to Clara Washington Bennett in gratitude for her years of service and friendship.

It was a public acknowledgement preserved in legal records of a relationship that had meant far more than the simple employer servant dynamic suggested by the 1878 photograph.

She kept the photograph her entire life, Naomi said, reviewing the estate inventory.

25 years carried from Richmond to Philadelphia, preserved after her death.

tracing Clara’s later life required help from genealogologists and family historians.

Elellanar Patterson’s cousin in Boston, whose research had first identified Clara’s school, became an invaluable partner.

Her name was Joyce Bennett, a descendant of Clara through her marriage to Reverend Thomas Bennett.

Joyce invited the research team to her home in Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood.

She was in her 70s, a retired librarian who had spent decades researching her family history.

Her dining room table was covered with documents, photographs, and artifacts she had collected.

I always knew great great grandmother Clara was special.

Joyce said, “My grandmother told stories about her, how she could make the most beautiful needle work, how she taught so many young women, how people came from all over to learn from her.

But I didn’t understand the full significance until you reached out.

” She showed them a photograph of Clara taken in the 1890s, showing her as a mature woman with graying hair dressed in dark, respectable clothing.

But what caught everyone’s attention was the shawl draped over her shoulders, a white shaw with elaborate embroidered edges showing the same symbols from the 1878 portrait.

She was still in coding, Helen said with awe.

Even in her later years, she was still working with the symbols.

Joyce pulled out a wooden box.

Clara left this to her daughter, my great-grandmother.

Inside are pieces of needle work, letters, and one very special item.

She opened the box carefully.

Inside were several examples of white work embroidery.

But beneath these was a bound notebook.

Its cover worn, but the pages well preserved.

“This is Clara’s teaching manual,” Joyce said, handing it to Naomi.

“She wrote it over many years to train teachers who would carry on the work.

My grandmother said Clara was very specific.

This manual should be preserved, but kept private within the family until the right time came to share it.

” Naomi opened the notebook with trembling hands.

The first page read, “A guide to silent language for the teaching of freedom’s art by Clara Washington Bennett.

A begun 1883 Boston, Massachusetts.

The manual was extraordinary.

Over more than a 100 pages, Clara had documented not just the symbols and their meanings, but the entire philosophy behind the coding system.

She explained how the symbols had evolved from African communication traditions, been adapted during slavery, and further developed after emancipation.

Each symbol was illustrated with careful drawings showing the stitching technique.

Clara explained how variations in stitch direction, thread count, and symbol placement could modify meaning.

She provided examples of encoding different types of information, routes, locations, warnings, identification codes.

But more than technical instruction, Clara wrote about the history and meaning of what she called freedom’s art.

She explained how enslaved women had used needle work as one of the few activities owners encouraged and how they had subverted this approval to create a secret communication system.

Our grandmothers were brilliant, Clara wrote.

They took the tools of their oppression and transformed them into tools of liberation.

This art must be preserved as testament to our ingenuity, our resistance, and our determination to be free.

The manual included case studies, specific examples of how the coded needle work had been used.

One story described coordinating a family’s escape from rural Virginia to Philadelphia.

Another detailed how information about employment opportunities in northern cities had been encoded and distributed through church networks.

Most remarkably, Clara documented her partnership with Elizabeth Hartwell, referring to her as Mrs.

H a true friend to our cause.

Preparing to share their findings required careful consideration.

Naomi and Marcus understood this wasn’t just an academic discovery.

It was the uncovering of sacred knowledge created and preserved by black women who had fought for survival and freedom.

They needed to approach the public presentation with respect and appropriate credit to the descendants and communities who had helped them.

They formed an advisory board that included Joyce Bennett and Ellanar Patterson and several scholars of African-American history and women’s studies.

The board helped them decide how to frame the narrative, what details to emphasize, and how to honor both Clara and Elizabeth while centering the story on black resistance and ingenuity.

Elizabeth’s role was important, Joyce said during one planning meeting.

But we need to be clear that she was an ally, not a savior.

The coding system existed before she met Clara.

The networks were built by black communities.

Elizabeth provided resources and cover, which was valuable and brave, but the brilliance and the resistance, that was our people’s work.

They decided to launch the public revelation through multiple channels simultaneously.

The Charleston Heritage Museum would host a major exhibition.

Academic papers would be published and a documentary would be produced featuring interviews with descendants, scholars, and community members.

Most importantly, they would release complete documentation of the coding system itself, making it freely available for education and study.

The advisory board debated this carefully, some worried about appropriation, but ultimately decided that Clara’s own words provided guidance.

She had written, “This knowledge should be shared when it is safe to do so, so that all may understand what we achieved.

” In February 2025, they held a press conference in Richmond in the building that had once been Elizabeth Hartwell’s home and was now a community center.

The room was packed with journalists, scholars, and community members.

Joyce Bennett and Ellanar Patterson sat in the front row along with dozens of other descendants.

Naomi presented the findings first, showing the 1878 photograph on a large screen and explaining how the discovery had unfolded.

She walked the audience through identifying the embroidered symbols, decoding their meanings, and tracing Clara and Elizabeth’s lives.

This photograph, she said, is one of the most sophisticated pieces of coded documentation from the 19th century.

It preserves not just images of two women, but an entire system of communication, resistance, and survival.

It’s a testament to the ingenuity and courage of black women who transformed oppression into liberation, one stitch at a time.

Marcus presented the historical context, explaining how the coding system fit into the broader landscape of post civil war resistance, how it connected to underground railroad traditions, and how it evolved to meet the needs of black communities facing Jim Crow violence.

But the most powerful moment came when Joyce Bennett stood to speak.

She held up a piece of needle work, a collar she had made herself using Clara’s teaching manual.

The white work symbols were clearly visible under the stage lights.

My great great grandmother Clara made sure this knowledge wouldn’t die.

Joyce said she understood that our history isn’t just about what was done to us, but what we did for ourselves.

She wanted us to know that we were never helpless, never passive.

We were always fighting, always resisting, always finding ways to protect each other and survive.

The room erupted in applause.

Many were crying, moved by the power of the story.

Two years after the initial discovery, in December 2026, the Charleston Heritage Museum hosted a gathering to mark the anniversary and unveil a permanent exhibition dedicated to the silent language.

The room was filled with people whose lives had been touched by the discovery.

Joyce Bennett was there, now working on a book about Clara’s life.

Elellanar Patterson attended, though she needed a wheelchair, surrounded by three generations of her family.

Dozens of other descendants had traveled from across the country.

Also present were representatives from institutions Elizabeth had supported, including First African Baptist Church.

The permanent exhibition was comprehensive.

It included the original photograph, Clara’s teaching manual, examples of coded needle work discovered since the initial revelation, letters from network participants, and documentation of how the system had been used well into the 20th century.

One section explored the technical aspects, how the encoding worked, what symbols meant, how information was layered.

Interactive displays allowed visitors to decode simple messages.

This was popular with younger visitors fascinated by the cryptographic elements, but the heart of the exhibition was a gallery dedicated to the women themselves.

Large portraits of Clara and Elizabeth hung side by side with detailed biographies explaining not just what they had done, but who they had been, their motivations, their courage, their commitment to justice.

The exhibition included a video installation featuring descendants sharing family stories.

Joyce Bennett spoke about learning needle work from her grandmother, not understanding then that she was learning a language of resistance.

Elellanar Patterson’s great-grandson, a college student, talked about how discovering his ancestors role in the network had changed his understanding of his family’s history.

Perhaps most moving was a section titled the thread continues, which documented how the discovery had inspired contemporary artists, activists, and educators.

Fiber artists had created new works incorporating the historical symbols.

Community organizations taught the needle work as cultural preservation.

Scholars had revised curricula to include the silent language.

The exhibition featured examples of student work.

Young people who had learned the symbols and created their own coded pieces addressing modern issues like voting rights, police violence, and educational equity.

They were using Clara’s tools to speak about their own struggles, connecting past resistance to present activism.

During the unveiling ceremony, Naomi stood before the assembled crowd and reflected on the journey.

When I first saw that photograph two years ago, I had no idea what I was looking at.

I saw a standard Victorian portrait, unremarkable except for its quality.

But Clara Washington and Elizabeth Hartwell knew exactly what they were creating.

They were building a time capsule, sending a message forward to us.

She gestured to the photograph, now beautifully displayed and lit.

They trusted that someday someone would look closely enough to see what they had hidden in plain sight.

They trusted that when the time was right, their story could be told safely and completely.

And they were right.

Marcus added his thoughts.

This discovery has changed how we understand resistance, creativity under constraint, and the sophistication of communication networks among formerly enslaved people.

But more than that, it’s reminded us to look more carefully at what we think we already understand.

How many other photographs, artifacts, and documents are sitting in archives, appearing ordinary, but holding extraordinary secrets? Joyce Bennett had the final word.

She stood with a teaching manual Clara had created, now carefully preserved in a climate controlled case, but digitized and available to anyone who wanted to study it.

Clara wrote in this manual that she wanted future generations to understand three things, Joyce said, her voice strong and clear.

First, that our ancestors were brilliant.

They created sophisticated systems of resistance using the simplest tools.

Second, that survival is an art form.

It requires creativity, courage, and community.

And third, that knowledge is power.

When we preserve and share our history, we honor those who came before and empower those who come after.

She looked around the room at the diverse crowd, descendants and scholars, young and old, black and white, all connected by this story of resistance and hope.

Clara and Elizabeth’s friendship crossed lines that their society said couldn’t be crossed.

Their work saved lives and preserved dignity.

Their foresight ensured that we would know their story.

And now it’s our responsibility to carry the thread forward, to tell these stories, to honor this legacy, and to remember that resistance takes many forms.

Sometimes as quiet as a stitch, sometimes as visible as a photograph, but always as powerful as the human spirit refusing to be broken.

As the ceremony concluded and people moved through the exhibition, examining the photographs and artifacts, trying their hands at the needlework stations, reading the testimonies and histories, Naomi felt a profound sense of completion.

The photograph that had puzzled her two years ago had revealed its secrets.

Clara and Elizabeth’s message sent across 148 years had finally been received and understood.

And in teaching rooms throughout the museum, young hands were learning to stitch the old symbols, ensuring that the silent language born in the darkest circumstances, but speaking of hope, resistance, and unbreakable will never be forgotten.

The thread continued unbroken from past to present to future, carrying with it the wisdom Clara had preserved.

That even in oppression, creativity flourishes.

That even in silence, powerful messages can be sent.

And that those who seek to erase history will always fail because someone somewhere will find a way to preserve the truth and pass it forward.

News

📜 POPE LEO XIV UNSEALS A FORBIDDEN SCROLL FROM THE VATICAN VAULTS — CLAIMS IT REVEALS CHRIST’S “FINAL COMMANDMENT” HIDDEN FOR 2,000 YEARS, AND NOW CARDINALS ARE SCRAMBLING TO EXPLAIN THE SILENCE 🕯️ In a candlelit archive beneath St. Peter’s, the pontiff allegedly unveiled brittle parchment that insiders say could rewrite everything believers thought they knew, sparking whispers of cover-ups, shattered dogma, and a Church terrified of its own past 👇

The Revelation of the Hidden Scroll: A Journey into Darkness In the heart of the Vatican, a storm was brewing….

💥 15 NEW REFORMS SHAKE THE VATICAN — POPE LEO XIV DROPS A HOLY HAMMER ON CENTURIES OF TRADITION, CARDINALS STUNNED, DOORS SLAMMED, AND WHISPERS OF “SCHISM” ECHO THROUGH ST. PETER’S 🔔 In a move insiders call “the most explosive shake-up since the Middle Ages,” the new pontiff reportedly blindsided bishops at dawn with sweeping decrees that rewrite worship, power, and money itself, leaving the marble halls trembling and the faithful wondering who’s really in charge now 👇

The Awakening of Faith: A Shocking Revelation In a world where faith was a flickering candle, struggling against the winds…

It was just a photo of two sisters — but it hid a dark secret

It was just a photo of two sisters, but it hid a dark secret. The photograph appeared ordinary at first…

It Was Just a Portrait of a Mother and Her Children — But When Experts Zoomed In, They Paled

It was just a portrait of a mother and her children. But when experts zoomed in, they pald. Rebecca Turner…

It was just a photo of a girl with flowers — until you notice what she’s hiding in her hand

It was just a photo of a girl with flowers, but what she’s holding in her hand tells a different…

It was just a photo of three friends — until researchers deciphered the hand signal they were making

It was just a photo of three friends until researchers deciphered the hand signal they were making. The New Orleans…

End of content

No more pages to load