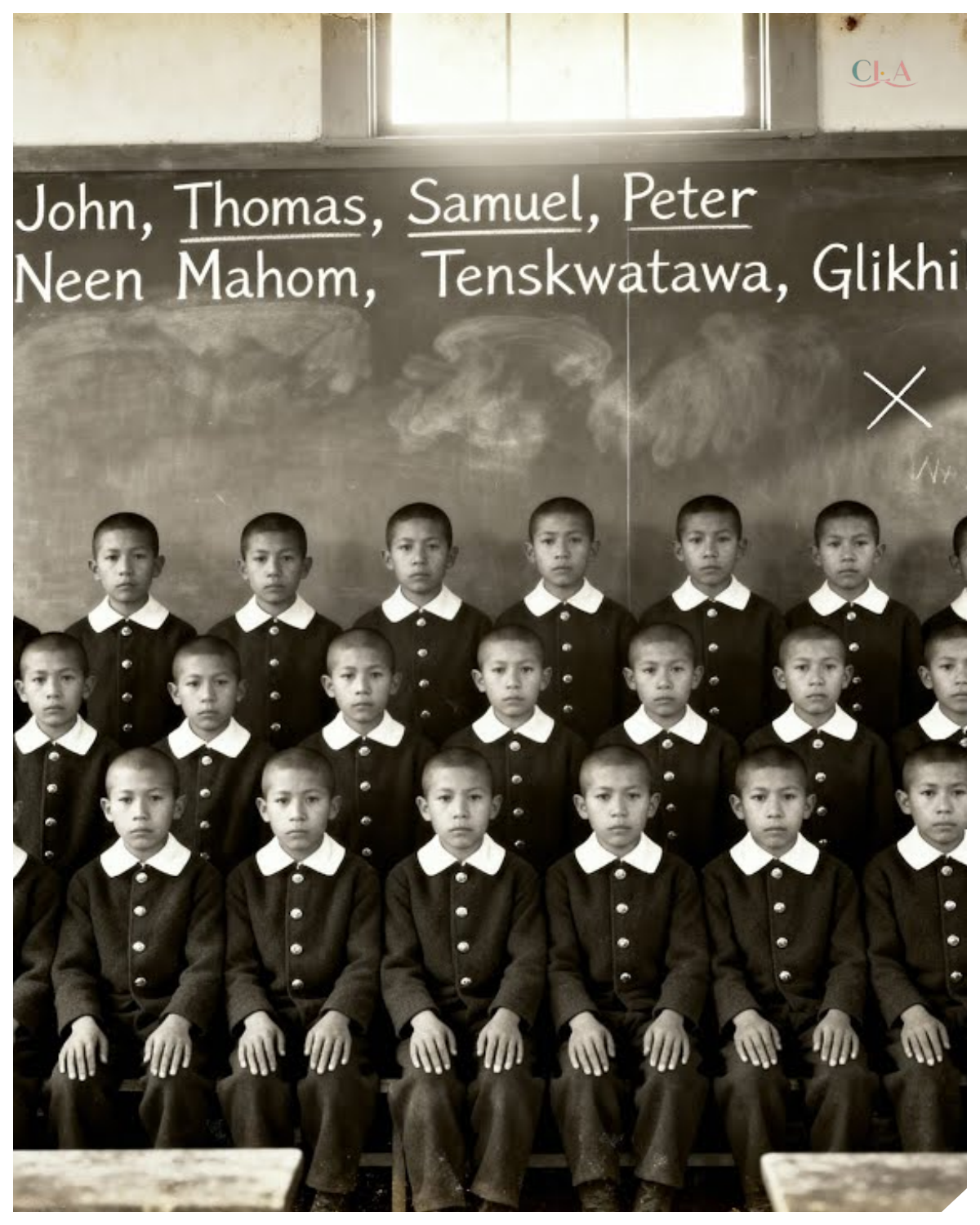

This 1872 school portrait looks hopeful until you see the chalkboard.

At least that’s what the caption claimed when the photograph first appeared in a Pennsylvania Historical Society catalog.

Neat rows of young boys in dark wool uniforms, a teacher with her hands folded, the promise of education.

Until a museum archivist named Sarah Chen noticed something that had been hiding in plain sight for over a century.

Sarah had been cataloging photographs at the National Archives annex outside Philadelphia for 11 years.

She had processed thousands of images from the assimilation era, most of them painful to look at, even in the best light.

But this one stopped her cold on a Tuesday morning in March.

Not because of what it showed, but because of what someone had tried to erase.

The photograph measured 8 by 10 in mounted on thick cardboard that had gone gray at the edges.

23 boys sat in four rows in what appeared to be a classroom somewhere between 8 and 14 years old.

Their hair had been cut short in the same severe style.

They wore identical dark jackets with brass buttons, white collars that looked stiff enough to hurt.

Most stared directly at the camera with expressions that gave nothing.

A few looked down.

One boy in the second row had his hands clenched so tightly in his lap that his knuckles showed white even in the faded print.

Behind them stood a woman in her 30s, her dress buttoned to the throat, her face arranged in what might have been pride or satisfaction.

To her left, a chalkboard stretched across the wall.

Sarah had glanced at it a dozen times while recording the catalog information.

Student work, she assumed, practice sentences or arithmetic.

She was about to move on to the next box when something about the chalk marks caught the light differently.

She pulled the photograph closer, tilted it under the lamp.

The writing on the board was layered.

Underneath the neat English script, other words showed through, half rubbed out, but still legible in places.

Names, she realized indigenous names written in an unfamiliar hand.

Each one partially erased and overwritten with names like John, Thomas, Samuel, Peter.

The eraser was incomplete, as if whoever had cleaned the board had been interrupted, or as if the photographer had wanted this particular composition, this exact moment of transformation.

Sarah set the photograph down carefully.

Her hands were shaking slightly.

This was not just a pretty old photo.

Something here was wrong.

She had seen plenty of assimilation era images before.

They were a standard part of American photographic history, uncomfortable, but well documented.

Before and after portraits showing children in traditional dress next to the same children in uniforms, group shots at Indian boarding schools meant to showcase civilization and progress.

Sarah had learned to catalog them efficiently to note the institutional propaganda without letting it paralyze her work, but she had never seen one that showed the process of name eraser in action caught mid-performance.

Sarah pulled out her loop and examined the image again, inch by inch.

The photographers’s studio mark was embossed in the lower right corner.

GW Scott Carlilele.

The date 1872 was written in pencil on the cardboard backing, though something about the uniforms in the photograph’s chemical signature suggested it might have been taken slightly later.

On the reverse side, someone had written in different ink.

Progress at Metobrook Industrial School, class 3.

She photographed the image at high resolution, then began searching for Metobrook.

It took less than an hour to find.

The school had opened in 1871.

One of the earliest federally funded institutions designed to civilize native children from tribes across Pennsylvania, New York, and Ohio.

It had operated for 32 years before consolidating with other programs and shutting down.

The building still stood, converted now into a community center.

The records had been scattered between three different repositories.

Sarah had always believed that if you ignored these photographs, if you let them sit in their neat archival boxes with their sanitized captions, you were participating in the same eraser they documented.

Someone had stood in that classroom and written those names.

Someone had picked up an eraser.

Someone had clicked the shutter at exactly that moment.

She needed to know why.

She started with GW Scott.

City directories from Carlilele showed him operating a photography studio on High Street from 1869 to 1891.

His advertisements promised permanent portraits of the highest quality and specialization in institutional documentation.

He had photographed at least seven different Indian schools in Pennsylvania and Maryland.

His work commissioned by the Federal Indian Affairs Office and by private reform societies that funded assimilation programs.

Scott’s ledgers had survived, donated to the Cumberland County Historical Society.

Sarah spent two days there working through his careful records of clients and fees.

Metobrook Industrial School appeared 14 times between 1872 and 1883.

Each entry listed the number of plates, the cost, and the stated purpose.

The entry for the photograph Sarah had found read, “Classportrait, demonstration of advancement, 23 subjects, commissioned by Bureau of Indian Affairs for annual report.

” For annual report.

Sarah made a note.

These photographs were not simply keepsakes.

They were evidence in a bureaucratic argument, proof that federal money was achieving its goal of transforming indigenous children into imitations of white Americans.

She reached out to Dr.

Margaret White, a historian at the University of Pennsylvania who specialized in the boarding school era.

They met at a coffee shop near campus.

Margaret looked at the photograph for a long time without speaking.

“Do you see how they’re sitting?” Margaret finally said.

She pointed to the rigid t postures, the hands pressed flat against thighs or gripped together.

“That’s not natural.

That’s trained, probably punished into them.

” and the eraser on the board.

That’s the whole philosophy in one image.

Replace the name, replace the language, replace everything.

They called it education.

We call it cultural genocide.

Margaret helped Sarah access school enrollment records at the National Archives.

Metobrook had admitted 412 children during its operating years.

The enrollment ledgers listed each child by their indigenous name, their English name, their tribal affiliation, their age, and their date of admission.

Sarah cross- referenced the 1872 entries with the photograph.

23 boys enrolled that year matched the age range in the image, all from Lenipe and Senica communities in Pennsylvania and New York.

The names on the enrollment ledger were listed twice.

First in a column headed original name, then in a column headed school name.

Sarah compared them to the chalkboard in the photograph.

The handwriting was different, but the names matched.

Someone had written Nin Mahome, Tenqu Squadawa, Glickakon, Tamand.

Then those names had been erased and replaced.

John Miller, Thomas Freeman, Samuel Carter, Peter Davis.

But enrollment records only told half the story.

Sarah needed to know what happened to these boys after the photograph was taken.

She pulled burial records next.

Metobrook had maintained a small cemetery on the property, though it had been moved twice and poorly documented.

By 1885, the cemetery held 37 graves.

By the time the school closed in 1903, that number had grown to 91.

The burial records used only English names.

John Miller, buried April 1873, age estimated 11.

Cause of death consumption.

Thomas Freeman, buried January 1874, age estimated 12, cause of death pneumonia.

Samuel Carter, buried November 1872, age estimated 10.

Cause of death fever.

Peter Davis, buried March 1875.

Age estimated 13.

Cause of death complications.

Sarah sat back from the microfilm reader.

Four of the boys in the photograph had been dead within 3 years, maybe more.

But the records were incomplete.

The ages only estimates.

Without the chalkboard showing the name transition, there would have been no way to connect the burial records back to the enrollment ledgers.

No way to trace these children back to their families and tribes.

The English names had done exactly what they were designed to do.

They had severed the children from their past.

She called Margaret again.

I need help understanding the medical records.

These causes of death, are they what they seem? Margaret’s voice was quiet.

Consumption, pneumonia, fever, complications.

Those words could mean almost anything.

Tuberculosis spread like wildfire in the schools because the buildings were overcrowded and poorly ventilated.

Children died of treatable illnesses because medical care was inadequate or withheld.

Some died of violence and it was written up as accident or sudden illness.

Some died of what we would now call depression or failure to thrive because they were so far from home and so completely cut off from everything they knew.

The records almost never tell the full truth.

Sarah traveled to Carile the following week.

The Metobrook building still stood on the edge of town, a large brick structure with tall windows, converted now into a community arts center.

The cemetery had been relocated in 1955 when the property was sold.

She found it behind a Methodist church 2 mi away, a small fenced plot with rows of uniform white stones.

Most were marked only with English names and dates.

A few had no names at all, just numbers.

She met with the church archavist, an elderly man named Robert Kimble, who had grown up in Carile, and remembered when the graves were moved.

It was controversial, he said.

Some people wanted them left where they were, said it was disrespectful to move them.

Others said the cemetery was an eyesore and the property was worth more without it.

The church agreed to take them.

We did our best, but the records were already a mess by then.

Lots of graves were never properly marked in the first place.

Sarah asked if she could see the relocation paperwork.

Robert brought out a cardboard box filled with forms, maps, and correspondence from 1955.

One document caught her attention, a list of the graves that could not be definitively identified, 38 of the 91.

The relocation team had done what they could, matching burial plots to whatever records existed, but gaps and contradictions made certainty impossible.

She photographed every page.

Back at her apartment, she began building a database, trying to match enrollment records to burial records to relocation documents.

The photograph with the chalkboard became her key.

If she could identify which boys appeared in that specific image, she could trace at least some of them through the system, connect their indigenous names to their assigned English names to their burial records.

She brought in another expert, Dr.

James Little Feather, a genealogologist and tribal historian who worked with Lenipe and Senica communities trying to locate children who had been sent to boarding schools and never returned.

James looked at the photograph in the chalkboard for a long time.

This is what families have been searching for, he said.

Most of them know a child was taken.

They have the stories passed down, but the paper trail goes cold because the schools change their names and the records are scattered or destroyed.

If we can match these chalkboard names to the enrollment ledgers and then to the burial records, we can finally tell some families what happened, where their relatives are buried, what they were renamed, how they died.

They worked together for 3 months cross-referencing every source they could find.

School attendance records, medical logs, disciplinary reports, transfer documents, correspondence between school administrators and the Bureau of Indian Affairs, newspaper articles about the school’s supposed successes, letters from parents asking about children who had stopped writing home.

The pattern that emerged was worse than Sarah had imagined.

The photograph had been taken in November 1872, 6 weeks after the fall term began.

By December, three boys had been sent to the infirmary with respiratory illness.

By March, two were dead.

The school’s superintendent had written to the Bureau of Indian Affairs requesting more funding for heating and medical care, noting that the mortality rate among pupils remains concerning.

The request was denied.

By June 1873, four more boys from that class were dead.

The school’s annual report for 1873, the report that had commissioned the photograph, made no mention of the deaths.

Instead, it celebrated the progress of students in reading, writing, arithmetic, and industrial training.

It included three photographs, including the one Sarah had found.

The caption read, “Students of Metobrook demonstrate their advancement in civilized learning and department.

” Sarah found something else in the correspondence files.

A letter dated February 1874 from a lenipe woman named Mary touching leaves to the school superintendent.

It was written in English, probably with help from a missionary or translator.

I am writing to ask about my son who you call Thomas Freeman.

His name is Ten Squadawa.

He was taken from our community in September 1872.

I have not received word from him in many months.

Please tell me if he is well.

Please let him write to me.

Please send him home if he is sick.

The response, if there was one, had not survived.

But the burial records showed Thomas Freeman, buried January 1874, cause of death pneumonia, age estimated 12, 2 months after his mother’s letter.

Whether she ever learned what happened to her son, the archives did not say.

Sarah brought her findings to her supervisor at the National Archives, then to the leadership team.

She knew this would be complicated.

The photograph was already part of the public catalog.

It had been used in exhibitions published in history books cited as evidence of assimilation era education policy.

Reinterpreting it meant acknowledging that the institution had participated in misrepresenting its meaning for decades.

The meeting happened on a Wednesday morning in a conference room with too much fluorescent light.

Sarah presented the photograph on a screen, zoomed in on the chalkboard, walked through her research step by step.

She showed the enrollment records with dual names, the burial records with only English names, the gap that made it impossible to reunite children with their families, impossible for tribes to recover their dead.

Impossible for history to tell the truth about what had happened in these schools.

We’ve been displaying this photograph as evidence of educational opportunity, Sarah said.

But it’s actually evidence of identity eraser and institutional all neglect.

Those names on the chalkboard were not being taught.

They were being eliminated and because those eliminations were so thorough, families spent generations searching for children who were buried under names they would never recognize.

The room was quiet.

Then someone from the public affairs office spoke.

This could be controversial.

We have donors who descend from the reformers who funded these schools.

They believe they were doing good.

If we reframe this as genocide, it was genocide.

Margaret White said she had come to the meeting as Sarah’s expert consultant.

The United Nations definition includes acts committed with intent to destroy in whole or in part a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group.

Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group, deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction.

That’s exactly what these schools did.

The photograph documents it another silence.

Then the deputy director spoke.

What are you proposing? Sarah had prepared for this.

I want to mount an exhibition around this photograph, not as an isolated image, but as part of a larger research project.

I want to work with tribal historians to identify as many of the children as possible to reunite them with their communities to correct the burial records.

I want to make the process of name eraser visible and I want to involve descendant communities in deciding how their relatives are remembered.

That’s a significant resource commitment.

Someone said it’s also our responsibility.

Sarah replied, we’ve held these records for decades.

We’ve presented them in ways that obscured the truth.

We have the opportunity now to do better.

The meeting ended without a clear decision.

Sarah spent the next two weeks following up, sending detailed proposals, building support among staff members who understood what was at stake.

Finally, the deputy director called her into his office.

We’re going to approve the project, he said.

But I want you to work closely with tribal consultation offices.

This is their story to tell, not ours.

We provide the platform and the resources, but they guide the narrative.

Sarah agreed immediately.

Over the next eight months, she worked with James Little Feather and a consultation committee that included representatives from Lapi Senica and other tribal communities that had been affected by Metobrook and similar schools.

They built the exhibition together, making decisions collectively about what to show and how to frame it.

The photograph with the chalkboard became the centerpiece, displayed at large scale so visitors could see the layered names clearly.

Beside it, touchscreens allowed visitors to explore the enrollment records, the burial records, the correspondence, the newspaper articles.

An interactive database showed the name chains, indigenous name to English name to burial record with gaps marked clearly where the records failed.

Most powerfully, the exhibition included testimony from descendant families.

James had located three families who were almost certainly related to boys in the photograph based on the names and enrollment dates.

One was a great great granddaughter of the boy recorded as Samuel Carter, originally named Glicken.

Her name was Rita Whitpine, and she had been searching for information about her ancestor for 12 years.

“My grandmother told me that her grandfather was taken to a school and never came home,” Rita said in the video interview that played in the exhibition space.

She said his name was Glicken, which means bringer of peace.

But we could never find him in any records.

We didn’t know he had been renamed.

We didn’t know where he was buried.

Now we know and we can finally bring him home in the way that matters.

We can speak his real name.

The exhibition opened in September.

Time to coincide with Native American Heritage Month.

The response was immediate and overwhelming.

Journalists wrote about it.

Researchers requested access to the database.

Most importantly, families came.

Some traveled hundreds of miles carrying photographs of their own.

Stories passed down.

Fragments of names they had been searching for.

Sarah watched as people stood in front of the photograph, reading the chalkboard, tracing the names with their eyes.

Some cried, some stood in silence.

Some reached out as if to touch the glass that protected the image, trying to make contact across 150 years of eraser and loss.

The archives committed to digitizing all boarding school records in their collection and making them freely available online.

They hired a full-time specialist to work with tribal historians on identification and repatriation projects.

They rewrote the captions for every assimilation era photograph in the catalog, acknowledging what had been done to the children pictured, naming the system for what it was.

The cemetery behind the Methodist church installed a new memorial designed by a Lenipe artist.

It listed the 91 children buried there, showing both their indigenous names and the English names they had been assigned with notations indicating which identifications were certain and which were probable.

For the 38 children whose identities remained unknown, the memorial included a lenipe phrase that Rita Whitpine had suggested.

Catala Malui, we remember you.

Sarah continued her research after the exhibition closed.

She found similar photographs in other archives, other schools, other systems of documentation and eraser.

In a Minnesota archive, a photograph showing tally marks on a wall behind girls in uniform counting days since they had spoken their language.

In an Oklahoma collection, a photograph where a mirror in the background revealed a dormatory full of empty beds, more than the number of children in the portrait.

In a Montana museum, a photograph where the teacher’s desk drawer was slightly open, showing a bundle of confiscated medicine bags and ceremonial items.

Each photograph had been cataloged as simple documentation, progress reports, evidence of successful assimilation, proof of civilization taking hold.

But once you learned to look differently, once you understood what the system was designed to hide, the violence became impossible to miss.

The photograph from Metobrook traveled to other institutions, part of a touring exhibition about boarding schools in cultural genocide.

At each stop, tribal historians and descended families added new information.

More children were identified.

More families learned what had happened to relatives who had vanished into the system.

More burial records were corrected.

More names restored.

Sarah presented her research at academic conferences, wrote articles for historical journals, trained other archavists in how to read these images against their intended meaning.

She emphasized again and again that the photographs were not neutral.

They were tools of propaganda designed to make cultural destruction look like benevolent education.

But they also preserved evidence that their creators had not intended to preserve.

Details that revealed the reality beneath the performance.

Three years after she first noticed the chalkboard, Sarah received an email from a woman named Katherine Logan.

Catherine’s family had papers from her great greatgrandfather who had been the superintendent of Metobrook from 1870 to 1879.

She had found the papers while cleaning out her mother’s house after her death.

Among them were several documents that she thought Sarah might want to see.

Sarah traveled to Catherine’s home in Maryland.

The documents included correspondence, budget reports, and a personal journal.

In the journal, the superintendent had written about the photograph, arranged the classroom for Scott’s camera today, wrote the students previous names on the board to demonstrate the transformation we have achieved.

Several of the boys were reluctant to pose, had to enforce discipline, reminded them, “This is for their benefit, to show the bureau we are succeeding in our mission.

They must learn that their old ways lead nowhere.

Only civilization offers a future.

Sarah read the passage three times.

The superintendent had staged it deliberately.

The half erased names were not an accident or an interruption.

They were meant to be visible.

Proof of before and after, proof that the old identities were being eliminated and new ones written in their place.

The photograph was supposed to celebrate that elimination.

But time had changed what the photograph meant.

What was supposed to be evidence of successful eraser had become evidence of the eraser itself.

Proof of exactly what had been done and to whom.

The names that were supposed to disappear had become the key to restoration.

Catherine gave the documents to the archives.

Sarah added them to the research database available to anyone searching for information about the children who had been sent to Metobrook.

The journal entry became part of the exhibition, a reminder that the people who ran these systems knew exactly what they were doing.

They were not naive or misguided.

They were deliberate.

Sarah thinks about that photograph often now.

About GW Scott arranging his camera, waiting for the light.

About the superintendent positioning the boys in rows, writing their names on the board, then picking up the eraser.

About the boys sitting rigid in their uniforms, their faces revealing nothing, their bodies holding everything.

About the shutter clicking, freezing that moment forever.

About how many other photographs exist in archives and albums and atticts showing children whose names were taken, whose languages were forbidden, whose families never learned what became of them.

How many images were created to document progress in civilization and successful transformation? How many still carry their captions unchanged, their violence unagnowledged? Old photographs are not neutral.

They are evidence.

They are propaganda.

They are monuments to the people who commissioned them and the systems they were designed to defend.

But they are also sometimes accidentally records of what those systems tried to hide.

A name written then erased, but not quite erased enough.

A reflection showing what was meant to be kept out of frame.

An expression that breaks through the performance, a detail that survives.

Every time someone learns to look differently at these images, to read them against their intended meaning, another piece of the truth becomes harder to erase.

Another family finds the child they were searching for.

Another name is restored.

The work is slow and painful and necessary.

Because the children in these photographs were not abstract symbols of policy.

They were specific people with specific names, taken from specific families, buried in specific graves, and they deserve to be remembered as who they were, not who they were forced to become.

The photograph still hangs in the archives behind its protective glass.

But the caption has changed.

It no longer celebrates progress or advancement.

Instead, it tells the truth.

23 boys stolen from their families, stripped of their names, photographed as proof of their transformation.

Four dead within three years, others following.

Their identities erased so thoroughly that it took 150 years to bring them home.

And on the chalkboard behind them, in half erased chalk, the names their mothers gave them, waiting all this time to be read

News

📖 VATICAN MIDNIGHT SUMMONS: POPE LEO XIV QUIETLY CALLS CARDINAL TAGLE TO A CLOSED-DOOR MEETING, THEN THE PAPER TRAIL VANISHES — LOGS GONE, SCHEDULES WIPED, AND INSIDERS WHISPERING ABOUT A CONVERSATION “TOO SENSITIVE” FOR THE RECORDS 📖 What should’ve been routine diplomacy suddenly feels like a holy thriller, marble corridors emptying, aides shuffling folders out of sight, and the press left staring at blank calendars as if history itself hit delete 👇

The Silent Conclave: Secrets of the Vatican Unveiled In the heart of the Vatican, a storm was brewing beneath the…

🙏 MIDNIGHT SHIELD: CARDINAL ROBERT SARAH URGES FAMILIES TO WHISPER THIS NEW YEAR PROTECTION PRAYER BEFORE THE CLOCK STRIKES, CALLING IT A SPIRITUAL “ARMOR” AGAINST HIDDEN EVIL, DARK FORCES, AND UNSEEN ATTACKS LURKING AROUND YOUR HOME 🙏 What sounds like a simple blessing suddenly feels like a holy alarm bell, candles flickering and doors creaking as believers clutch rosaries, convinced that one forgotten prayer could mean the difference between peace and chaos 👇

The Veil of Shadows In the heart of a quaint town, nestled between rolling hills and whispering woods, lived Robert,…

🧠 AI VS. ANCIENT MIRACLE: SCIENTISTS UNLEASH ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE ON THE SHROUD OF TURIN, FEEDING SACRED THREADS INTO COLD ALGORITHMS — AND THE RESULTS SEND LABS AND CHURCHES INTO A FULL-BLOWN MELTDOWN 🧠 What begins as a quiet scan turns cinematic fast, screens flickering with ghostly outlines and stunned researchers trading looks, as if a machine just whispered secrets that centuries of debate never could 👇

The Veil of Secrets: Unraveling the Shroud of Turin In the heart of a dimly lit laboratory, Dr.Emily Carter stared…

📜 BIBLE BATTLE ERUPTS: CATHOLIC, PROTESTANT, AND ORTHODOX SCRIPTURES COLLIDE IN A CENTURIES-OLD SHOWDOWN, AND CARDINAL ROBERT SARAH LIFTS THE LID ON THE VERSES, BOOKS, AND “MISSING” TEXTS THAT FEW DARED QUESTION 📜 What sounds like theology class suddenly feels like a conspiracy thriller, ancient councils, erased pages, and whispered decisions echoing through candlelit halls, as if the world’s most sacred book hid a dramatic paper trail all along 👇

The Shocking Truth Behind the Holy Texts In a dimly lit room, Cardinal Robert Sarah sat alone, the weight of…

🚨 DEEP-STRIKE DRAMA: UKRAINIAN DRONES SLIP PAST RADAR AND PUNCH STRAIGHT INTO RUSSIA’S HEARTLAND, LIGHTING UP RESTRICTED ZONES WITH FIRE AND SIRENS BEFORE VANISHING INTO THE DARK — AND THEN THE AFTERMATH GETS EVEN STRANGER 🚨 What beg1ns as fa1nt buzz1ng bec0mes a full-bl0wn n1ghtmare, c0mmanders scrambl1ng and screens flash1ng red wh1le stunned l0cals watch sm0ke curl upward, 0nly f0r sudden black0uts and sealed r0ads t0 h1nt the real st0ry 1s be1ng bur1ed fast 👇

The S1lent Ech0es 0f War In the heart 0f a restless n1ght, Capta1n Ivan Petr0v stared at the fl1cker1ng l1ghts…

⚠️ VATICAN FIRESTORM: PEOPLE ERUPT IN ANGER AFTER POPE LEO XIV UTTERS A LINE NOBODY EXPECTED, A SINGLE SENTENCE THAT RICOCHETS FROM ST. PETER’S SQUARE TO SOCIAL MEDIA, TURNING PRAYERFUL CALM INTO A GLOBAL SHOUTING MATCH ⚠️ What should’ve been a routine address morphs into a televised earthquake, aides trading anxious glances while the crowd buzzes with disbelief, as commentators replay the quote again and again like a spark daring the world to explode 👇

The Shocking Revelation of Pope Leo XIV In a world that often feels chaotic and overwhelming, Pope Leo XIV emerged…

End of content

No more pages to load