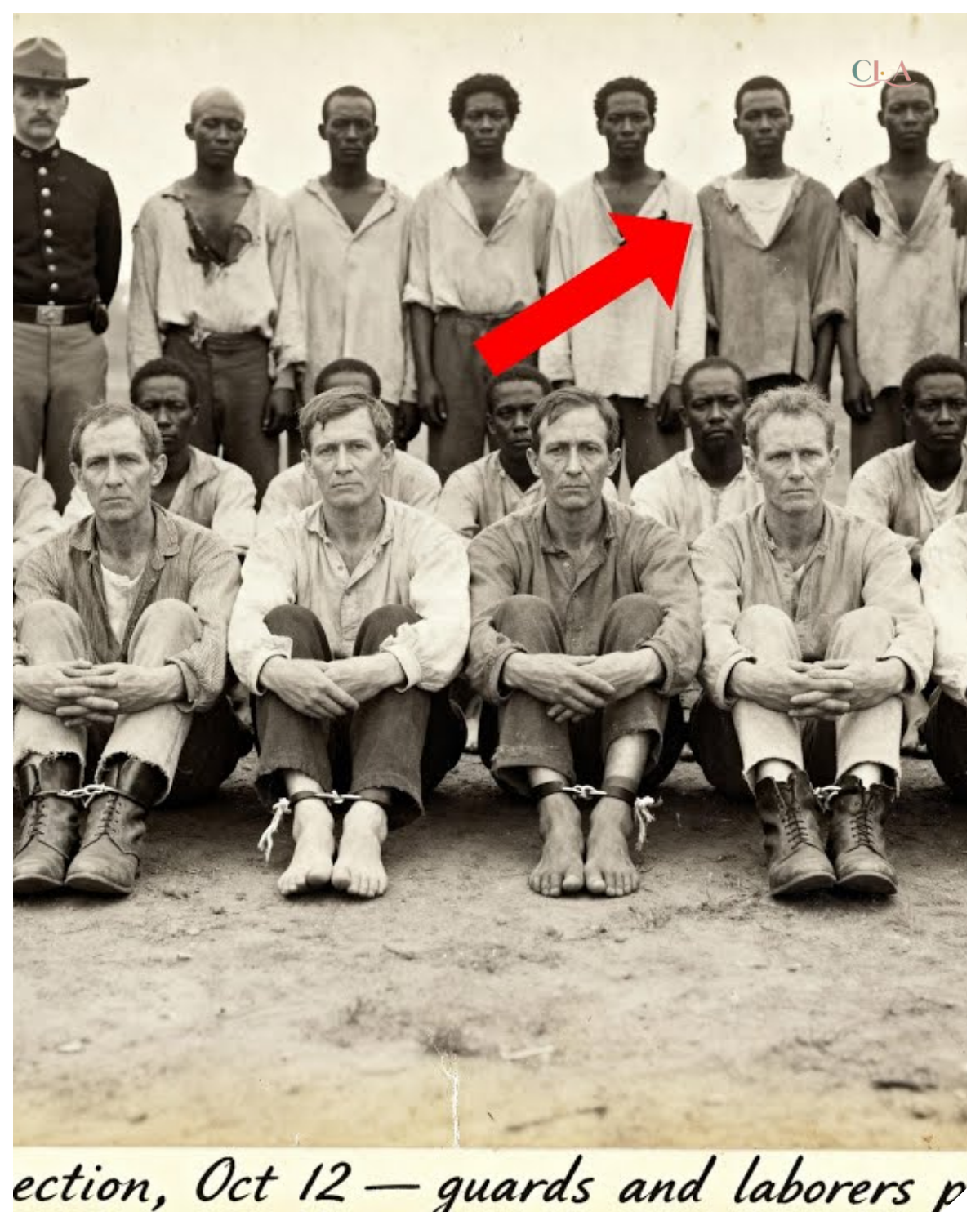

This 1864 prison camp photo looks orderly until you notice the boots.

The image had been celebrated for decades as proof of Union compassion.

Rows of Confederate prisoners seated peacefully on bare ground.

Union officers standing at attention, a model of wartime civility.

But in the spring of 2019, a Civil War photograph specialist named Margaret Hail could not stop looking at the feet.

She stood in the climate controlled basement of the National Archives annex in College Park, Maryland, a place she had visited at least twice a month for the past 11 years.

Hail had cataloged hundreds of prison camp images, most of them bleak and formulaic.

This one labeled simply Camp Sumpter Vicinity GA October 1864 had always been filed among the better examples.

The kind historians showed to counter narratives about Civil War cruelty.

Clean composition, visible order, no obvious suffering.

But that morning, under the white glow of the examination lamp, Hail noticed something that made her lean closer.

The photograph showed 40 or so Confederate prisoners seated in neat rows, their faces gaunt, but resigned.

Five Union officers stood to the left, postures stiff, hands clasped behind their backs.

Behind the prisoners, almost out of focus, stood a line of perhaps 12 black men.

They wore no uniforms.

Their shirts hung loose and patched.

And every single one of them was barefoot.

Hail adjusted her magnifying loop and moved it slowly along the bottom third of the image.

The seated Confederate prisoners wore boots.

Most looked worn but intact.

But as her eye tracked across the rows, she noticed something else.

Several pairs of boots were clearly too small.

One man’s feet bulged over the sides.

Another’s toes were visibly cramped, the leather splitting along the seams.

A third prisoner sat with his boots unlaced entirely as though he could not bear to tie them closed.

And then there was the background.

The barefoot black men stood close together, their arms crossed or hanging stiffly at their sides.

Hail zoomed in on their ankles, even through the grain of the albiman print.

She could see it.

Faint discoloration, rings of darker skin, slightly swollen, the kind of marking that came from wearing iron for weeks or months at a time.

Hail sat down the loop and felt the air go still in her chest.

This was not just a pretty old photo.

Something here was wrong.

Margaret Hail had worked as a photographic archavist for 16 years.

The last 11 focused almost exclusively on Civil War era images.

She had examined thousands of portraits, battlefields, camp scenes, and propaganda stills.

She knew the visual grammar of the period.

She knew how officers posed to project authority, how prisoners were arranged to look subdued but not degraded, how photographers framed scenes to tell the story their patrons wanted told.

This image had always been treated as neutral documentation, a snapshot of order and restraint.

But Hail could no longer see it that way.

She returned to her small office on the second floor and pulled out her notebook.

The print had been donated in 1923 by the estate of a Union officer’s descendant along with a collection of other camp images.

The accompanying documentation described it as evidence of humane treatment at an auxiliary camp near Andersonville, one of the sites used to process Confederate prisoners before transfer or exchange.

Hail photographed the print with her highresolution scanner, zooming in on the barefoot men, the ill-fitting boots, and the ankle rings.

Then she carefully removed the photograph from its archival sleeve and turned it over.

On the back in faded pencil, someone had written, “Camp inspection, October 12th.

Guards and laborers present.

” Laborers, not soldiers, not freed men, not contraband, the term the Union had used early in the war for escaped enslaved people who crossed into Union lines, just laborers.

Hail felt a tightness in her throat.

She had seen that word before used in payroll records and quartermaster logs.

It was a bureaucratic euphemism that flattened people into function.

But this image suggested something darker.

These men were not paid workers.

They were not volunteers.

They were standing behind prisoners of war, unshot and marked, while white captives wore boots that did not fit.

She opened her laptop and began her search.

The photographer was listed as J.

A.

Kulie, a contract photographer who had worked for the Union Army’s quartermaster department in Georgia during the last year of the war.

Hail found his name in several military records.

Kulie had been hired to document infrastructure and supply lines, not battlefield glory.

His images were meant for bureaucrats, not the press.

That made this photograph unusual.

Why had Culie been sent to photograph a prison inspection? Hail spent the next two days combing through directories, regimental histories, and local archives.

She found the camp referenced in a handful of reports.

It had been a satellite facility, smaller than the notorious Andersonville stockade, but part of the same logistical network.

According to official accounts, it had housed overflow prisoners during the autumn of 1864 after Sherman’s forces pushed deeper into Georgia.

The reports emphasized efficient management and low mortality rates, especially compared to Andersonville itself.

But those reports never mentioned the laborers.

Hail contacted Dr.

Raymond Cole, a historian at Howard University who specialized in the transition from slavery to freedom during the Civil War.

She sent him the scanned image and her notes.

Cole called her back within 3 hours.

This is extraordinary,” he said, his voice quiet and deliberate.

“Do you know what you have here?” Hail admitted she was not sure.

Cole explained, “After the Emancipation Proclamation took effect in January 1863, the Union Army had struggled with what to do with the flood of formerly enslaved people who sought refuge in Union controlled territory.

Many were put to work.

Some were paid, though often in script or rations rather than real wages.

Others were simply impressed into service.

The line between employment and coercion was thin and often invisible.

In Georgia, that line disappeared entirely.

By late 1864, Cole said the Union was managing thousands of Confederate prisoners and dealing with supply shortages.

At the same time, you had tens of thousands of black refugees with nowhere to go.

The army didn’t see them as soldiers or citizens.

They saw them as a labor pool.

Cole asked Hail to zoom in on the ankle rings again.

She did.

That’s not accidental scarring.

Cole said those men were shackled recently, maybe days before this photo was taken.

And if they’re standing in a prison camp barefoot, while white prisoners are sitting with boots, you’re looking at forced labor, probably unpaid, possibly under threat.

Hail asked the question that had been gnawing at her since that first morning.

Why would the prisoners have boots that don’t fit? Cole paused.

Because those aren’t their boots.

Hail felt her stomach turn.

She spent the next three weeks traveling between archives, first to the Georgia Historical Society in Savannah, then to a small county museum near the site where the camp had once stood.

The land was now farmland, unmarked except for a historical plaque that mentioned Andersonville in passing.

At the county museum, a retired school teacher named Evelyn Moore helped Hail dig through boxes of unsorted documents.

Most were property deeds, tax records, and church bulletins.

But buried in a file marked Civil War MSE was a handwritten ledger.

It had no cover, no title page, just columns of names, dates, and notations.

Hail recognized it immediately.

It was a labor log.

The entries ran from August 1864 to January 1865.

Each line listed a man’s first name, sometimes a surname, and a task.

Digging latrines, hauling water, clearing brush, burying the dead.

Next to many names was a notation in a different hand.

No shoes requisition denied.

On October 10th, 2 days before the photograph was taken, someone had written 12 men, camp detail, no issue, no issue, meaning no supplies provided, no boots, no uniforms, no pay.

Hail photographed every page.

Back in Maryland, she contacted another expert, Dr.

Lette Fornier, a legal historian at Georgetown, who had written extensively about panage and forced labor in the post-war South.

Hail sent her the ledger images in the photograph.

Fornier’s response was immediate and unequivocal.

This is debt pinage in real time, Forier wrote.

And it’s happening under Union authority.

Fornier explained the mechanics.

After the war, southern states would formalize systems of convict leasing and debt bondage to reinsslave black workers under the guise of legality.

But during the war in Union occupied zones, similar practices were already emerging informally.

Black men and women were often told they owed the army for food, shelter, or transport.

Those debts were used to justify forced labor.

And because the laborers were not soldiers, they had no legal recourse.

The boots, Fornier argued, were evidence of an even uglier system.

If you’re a union officer managing a camp, you need labor, she wrote.

But you also need to keep prisoners alive for exchange purposes.

So, you create a barter.

You give the laborers nothing, not even shoes.

But you take shoes from the prisoners who still have them, and trade them for compliance.

Maybe you tell the prisoners they’ll get better rations if they cooperate.

Maybe you just take the boots by force.

Either way, the black laborers stay barefoot and exploited, and the prisoners stay dependent.

Hail read the email twice, then stared at the photograph on her screen.

The Union officers in the image were not villains.

They looked tired, bureaucratic, ordinary.

But they were standing in front of a system that had taken people who were supposed to be free and turned them into anonymous laborers, unclothed and unmarked, except by the violence they had already endured, and someone had taken a photograph to prove the camp was humane.

Hail printed the image and pinned it to her wall.

Then she began searching for descendants.

She found them through church records.

One of the names in the labor ledger, a man listed only as Samuel 34, camp detail, matched a baptism record from a freed men’s church in Mon, Georgia, dated April 1866.

The entry noted Samuel Freeman along with his wife Celia and two daughters.

The record also included a brief notation formerly held at camp released January 1865.

Hail traced the Freeman family forward.

They had stayed in Georgia, sharecropping for two generations before migrating north during the 1920s.

By 2019, there were descendants in Detroit, Atlanta, and Washington, DC.

She contacted one of them, a retired postal worker named Jerome Freeman, whose great greatgrandfather had been Samuel.

Freeman agreed to meet her at a coffee shop in Silver Spring.

“I knew he’d been in a camp,” Freeman said, stirring his coffee slowly.

“But we were always told he’d been a soldier.

That’s what the family story said.

A soldier.

Hail showed him the photograph.

Freeman studied it for a long time.

He didn’t ask which man might be his ancestor.

He looked at all 12 barefoot men standing in the back.

He wasn’t a soldier, Freeman said quietly.

He was just used.

Hail explained what she had found.

The ledger, the boots, the system of coercion that had operated even in Union camps.

Freeman listened without interrupting.

When she finished, he asked a single question.

Are people going to see this? Hail promised him they would.

But getting an institution to agree was harder than she expected.

In June 2019, Hail presented her findings to the curatorial board at the National Museum of American History in Washington, DC.

The photograph had been on loan there for a traveling exhibition about Civil War memory.

Hail proposed recontextualizing it in a new exhibit about labor and emancipation.

The room went quiet.

One board member, a Civil War scholar named Dr.

Philip Grayson, spoke first.

“I don’t dispute the evidence,” he said carefully.

“But this image has been used for years to show the Union’s restraint.

If we reframe it as exploitation, we risk undermining the entire narrative of Union moral authority.

” Hail kept her voice steady.

“The narrative was always incomplete,” she said.

“We just chose not to see the people standing in the back.

” Another board member, the museum’s director of development, raised concerns about donors.

Several major contributors to the museum’s Civil War collection, were descendants of Union officers.

Reframing a celebrated image as evidence of abuse could be seen as an attack on their legacy.

Hail understood the political calculus, but she also understood what was at stake.

“This photograph has always told a story,” she said.

“We just told the wrong one.

Those men were promised freedom and got servitude.

They stood there barefoot while we praised the camp’s humanity.

If we don’t correct that now, we’re complicit in the same eraser.

Dr.

Raymond Cole, who had been invited to consult, added his voice.

This isn’t about condemning individuals, he said.

It’s about showing how systems of exploitation adapted.

Emancipation was real, but it was incomplete.

And images like this are proof.

The board debated for 2 hours.

In the end, they agreed to move forward, but the exhibit would include a panel explaining the controversy, the evidence, and the ongoing questions about memory and interpretation.

It was not everything Hail wanted, but it was enough.

The exhibition opened in February 2020, just weeks before the pandemic shut down museums across the country.

But in those brief weeks, thousands of people saw the photograph in its new context.

The wall text was blunt.

This image was long celebrated as evidence of humane treatment in Union prison camps.

Recent research reveals a darker story.

The barefoot black men in the background were likely freed men forced into unpaid labor.

Their ankles show signs of recent shackling.

The boots worn by Confederate prisoners appear to have been taken from laborers or traded under coercion.

This photograph does not show compassion.

It shows how liberation was undermined even as it was proclaimed.

Beside the photograph, the museum displayed excerpts from the labor ledger, Samuel Freeman’s baptism record, and a brief oral history recorded by Jerome Freeman.

In the recording, Freeman spoke about what it meant to learn his ancestors real.

I used to think emancipation meant freedom, he said.

But it just meant a different kind of cage, and they didn’t even let him keep his shoes.

The exhibit received mixed responses.

Some visitors thanked the museum for honesty.

Others complained that it was revisionist.

One descendant of a union officer wrote a furious letter accusing the curators of dishonoring his family.

But the most powerful response came from other descendants of black laborers who had worked in union camps.

They came forward with their own family stories, letters, diaries, fragments of memory passed down through generations.

stories of men who had fled slavery only to be impressed into service, who had expected wages and received threats, who had been told they were free, but found themselves locked into systems they could not escape.

Hail collected those stories.

She archived them.

She made sure they were added to the museum’s permanent record.

The photograph itself remained on display, but now it was surrounded by context.

Visitors could no longer look at it and see only order.

They had to see the people who had been rendered invisible.

They had to confront what had been hidden in plain sight.

Hail visited the exhibit one last time before the museum closed for the pandemic.

She stood in front of the photograph, the same image she had first examined in the basement of the National Archives, and she thought about how easy it had been to miss the truth.

Not because the evidence was absent, because people had chosen not to look.

Old photographs are not neutral.

They never were.

Every frame is a choice.

Every pose, a performance, every caption, a story told by someone with power.

The camera does not lie, but the people behind it do.

They crop out what they do not want seen.

They frame suffering as order.

They turn exploitation into efficiency.

This photograph was no different.

For more than a century, it had been used to tell a story about union decency, about restraint and civilization in the midst of war.

But that story required ignoring the barefoot men in the back.

It required not asking why prisoners had boots that did not fit.

It required accepting that laborers was just a bureaucratic term and not a euphemism for something uglier.

Margaret Hail had spent her career looking at images like this.

And she had learned that the most important details are often the ones people are trained not to see.

the feet, the hands, the faces in the background, the people whose names were never recorded, whose labor was never compensated, whose freedom was never fully real.

This image is not unique.

There are hundreds like it in archives across the country.

Photographs of chain gangs labeled as work crews, images of children in fields described as apprentices, portraits of families posed with servants whose bondage was called something else.

Every one of those images is evidence not of progress, but of continuity, not of liberation, but of adaptation, not of justice, but of how power reshapes itself to look respectable.

The 12 barefoot men in this photograph were supposed to be free.

They had crossed into Union lines.

They had survived.

They had done everything they were supposed to do.

And still, they stood there without shoes, marked by shackles they were no longer wearing, while the people who enslaved them were praised for their humanity.

That is the story this photograph tells.

News

🌲 IDAHO WOODS HORROR: COUPLE VANISHES DURING SOLO TRIP — TWO YEARS LATER FOUND BURIED UNDER TREE MARKED “X,” SHOCKING AUTHORITIES AND LOCALS ALIKE ⚡ What started as a quiet getaway turned into a terrifying mystery, as search parties scoured mountains and rivers with no trace, until hikers stumbled on a single tree bearing a carved X — and beneath it, a discovery so chilling it left investigators frozen in disbelief 👇

In August 2016, a pair of hikers, Amanda Ray, a biology teacher, and Jack Morris, a civil engineer, went hiking…

⛰️ NIGHTMARE IN THE SUPERSTITIONS: SISTERS VANISH WITHOUT A TRACE — THREE YEARS LATER THEIR BODIES ARE FOUND LOCKED IN BARRELS, SHOCKING AN ENTIRE COMMUNITY 😨 What began as a family hike into Arizona’s notorious mountains turned into a decade-long mystery, until a hiker stumbled upon barrels hidden in a remote canyon, revealing a scene so chilling it left authorities and locals gasping and whispering about the evil that had been hiding in plain sight 👇

In August of 2010, when the heat was so hot that the air above the sand shivered like coals, two…

⚰️ OREGON HORROR: COUPLE VANISHES WITHOUT A TRACE — 8 MONTHS LATER THEY’RE DISCOVERED IN A DOUBLE COFFIN, SHOCKING AN ENTIRE TOWN 🌲 What began as a quiet evening stroll turned into a months-long nightmare of missing posters and frantic searches, until a hiker stumbled upon a hidden grave and police realized the truth was far darker than anyone dared imagine, leaving locals whispering about secrets buried in the woods 👇

On September 12th, 2015, 31-year-old forest engineer Bert Holloway and his 29-year-old fiance, social worker Tessa Morgan, set out on…

🌲 NIGHTMARE IN THE APPALACHIANS: TWO FRIENDS VANISH DURING HIKE — ONE FOUND TRAPPED IN A CAGE, THE OTHER DISAPPEARS WITHOUT A TRACE, LEAVING INVESTIGATORS REELING 🕯️ What started as an ordinary trek through the misty mountains spiraled into terror when search teams stumbled upon one friend locked in a rusted cage, barely alive, while the other had vanished as if the earth had swallowed him, turning quiet trails into a real-life horror story nobody could forget 👇

On May 15th, two friends went on a hike in the picturesque Appalachian Mountains in 2018. They planned a short…

📚 CLASSROOM TO COLD CASE: COLORADO TEACHER VANISHES AFTER SCHOOL — ONE YEAR LATER SHE WALKS INTO A POLICE STATION ALONE WITH A STORY THAT LEFT OFFICERS STUNNED 😨 What started as an ordinary dismissal bell spiraled into candlelight vigils and fading posters, until the station doors creaked open and there she stood like a ghost from last year’s headlines, pale, trembling, and ready to tell a truth so unsettling it froze the entire room 👇

On September 15th, 2017, at 7:00 in the morning, 28-year-old teacher Elena Vance locked the door of her home in…

🌵 DESERT VANISHING ACT: AN ARIZONA GIRL DISAPPEARS INTO THE HEAT HAZE — SEVEN MONTHS LATER SHE SUDDENLY REAPPEARS AT THE MEXICAN BORDER WITH A STORY THAT LEFT AGENTS STUNNED 🚨 What began as an ordinary afternoon spiraled into flyers, helicopters, and sleepless nights, until border officers spotted a lone figure emerging from the dust like a mirage, thinner, quieter, and carrying answers so strange they turned a missing-person case into a full-blown mystery thriller 👇

On November 15th, 2023, 23-year-old Amanda Wilson disappeared in Echo Canyon. And for 7 months, her fate remained a dark…

End of content

No more pages to load