This 1863 photo of two women looks elegant until historians revealed their true roles.

Dr.Rebecca Torres had spent 15 years studying Civil War photography, but nothing prepared her for what she found.

On a quiet Tuesday morning in March 2019, the archives of the Charleston Historical Society were dimly lit, smelling of old paper and preservation chemicals.

She sat at a wooden table, carefully turning pages of a leatherbound catalog labeled Southern Portraits, 1860 1865.

The photograph appeared on page 47.

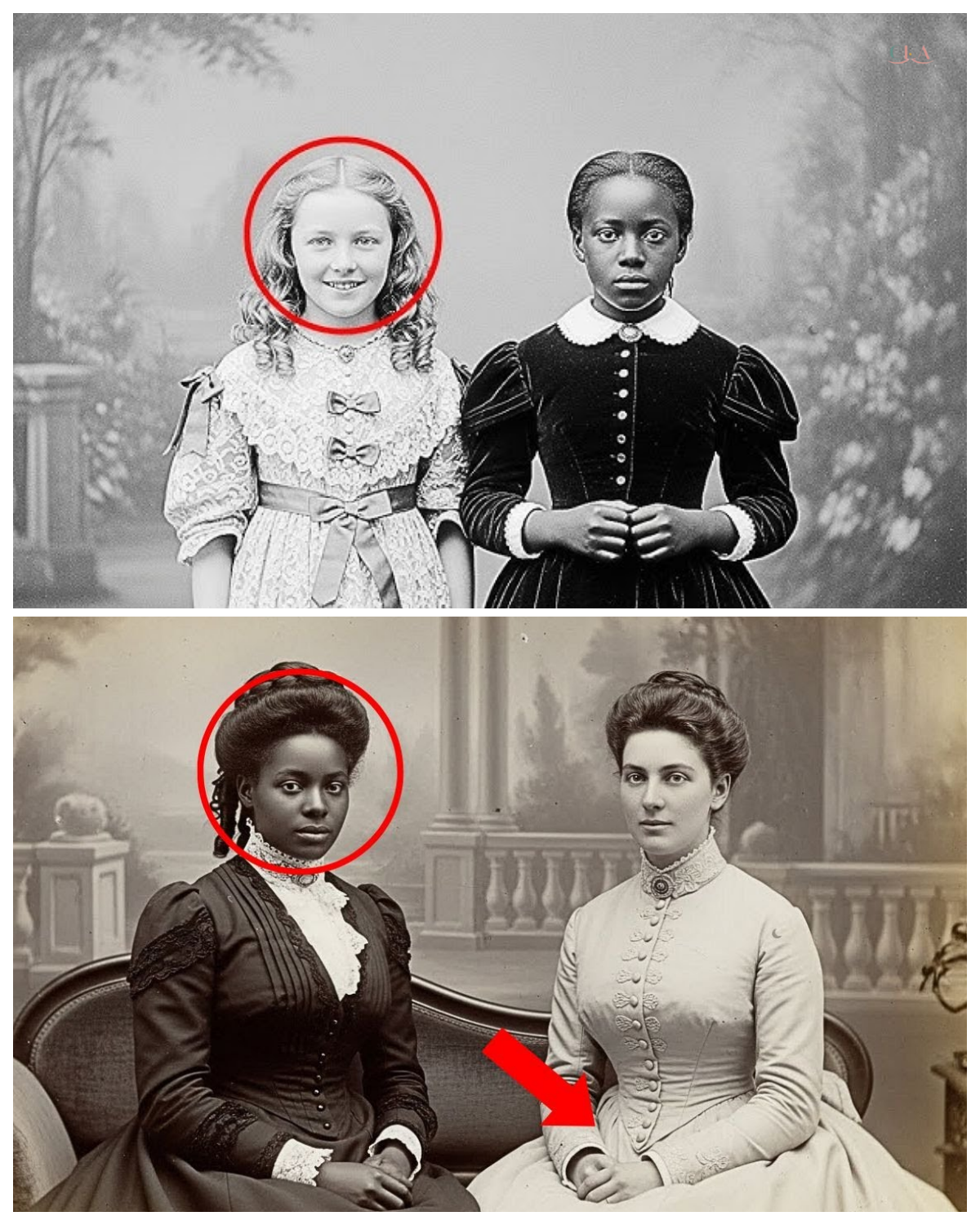

Two women seated side by side in an elegant photography studio.

Both wore elaborate silk dresses with intricate lace collars.

Their hair was styled in the fashion of the 1860s pinned up with careful precision.

The image was remarkably well preserved.

The details sharp despite its age.

The catalog entry read simply, “Two ladies of Charleston, 1863.

Unknown subjects.

” Rebecca adjusted her magnifying glass and leaned closer.

Something about the image caught her attention.

A subtle dissonance she couldn’t quite name.

The woman on the left sat with her hands folded primly in her lap, her posture perfectly erect, chin slightly raised.

The woman on the right held a similar pose, but there was something different in her eyes, attention in her shoulders that seemed almost imperceptible.

Rebecca photographed the image with her digital camera, then continued through the catalog.

But her mind kept returning to that photograph.

Over lunch, she pulled up the image on her laptop, zooming in on different sections.

That’s when she saw it.

On the right woman’s wrist, barely visible beneath the lace cuff of her sleeve, was a thin, dark line.

Rebecca enlarged the image further.

It wasn’t a shadow or a photographic artifact.

It was a mark, a scar perhaps, or something else entirely.

Her heart began to beat faster.

She zoomed in on the women’s hands.

The left woman’s hands were smooth, unblenmished.

The right woman’s hands, despite the elegant gloves she wore, showed calluses at the base of her fingers, visible even through the fabric when examined closely enough.

Rebecca sat back in her chair, her mind racing.

In 1863, Charleston, in the heart of the Confederacy, who would photograph two women together in such formal equality, and why would one of them bear the marks of hard labor while dressed as a lady? She opened her notebook and wrote a single question.

Who were they really? The investigation that would consume the next eight months of her life had just begun.

Rebecca returned to the archives the next morning with renewed purpose.

She requested all records related to photography studios operating in Charleston between 1860 and 1865.

The archivist, an elderly man named Mr.

Harrison, raised his eyebrows but retrieved three boxes of documents.

“Looking for something specific, Dr.

Torres?” he asked, setting the boxes on her table.

“A photograph?” she said, showing him the image on her laptop.

Do you recognize the studio backdrop? Mr.

Harrison squinted at the screen, then nodded slowly.

That’s Whitmore’s studio.

See the painted column and the velvet drape? Jonathan Whitmore had a studio on King Street.

He was known for photographing wealthy families.

Rebecca spent the day combing through Whitmore’s business records.

The leather ledgers were fragile, their pages yellowed and brittle.

She found entries for dozens of photographs.

Families, soldiers departing for war, couples on their wedding day.

Each entry included a date, the subject’s names, and the price paid.

Then on a page dated September 14th, 1863, she found an entry that made her breath catch.

Two subjects, private sitting, payment received in advance.

No names recorded per client request.

Rebecca photographed the page, a private sitting with no names, highly unusual for the period.

Photographers typically recorded their subjects for business purposes and future orders.

She researched Whitmore himself.

Born in Boston in 1822, he’d moved to Charleston in 1855 and established his studio.

But what caught her attention was a newspaper article from 1866 after the war ended.

Whitmore had testified in a local court case and the reporter noted that he was known for his abolitionist sympathies, though he kept such views private during the war years.

An abolitionist photographer in Confederate Charleston.

Rebecca felt pieces of a puzzle beginning to emerge.

She cross referenced the date, September 14th, 1863, with historical events.

The siege of Charleston had intensified that summer.

Union forces were closing in.

The city was under constant threat, its residents anxious and afraid.

Why would two women risk a photography session during such dangerous times? And why demand anonymity? Rebecca closed her laptop as the archives prepared to close for the evening.

Outside, Charleston’s historic district glowed in the golden hour light.

She walked past elegant homes with their characteristic porches and iron work, imagining what secrets these streets had witnessed.

Tomorrow, she would begin searching property records and plantation registries.

Somewhere in those documents, she believed were the names of the two women in the photograph.

Rebecca’s next step led her to the Charleston County property records.

She focused on households near Whitmore’s studio that would have had the wealth to commission such a formal photograph.

The list was surprisingly short.

By 1863, many wealthy families had fled Charleston’s increasing dangers.

One name appeared repeatedly in the records, the Asheford household.

They owned a rice plantation 15 mi outside the city, but maintained a townhouse on Meeting Street, just blocks from Whitmore Studio.

Rebecca requested estate documents for the Ashford family.

What arrived was a thick folder containing wills, property transfers, and most valuable, a household inventory from 1864.

The inventory listed the family members.

Richard Ashford, age 52, plantation owner.

His wife had died in 1859.

His daughter, Elizabeth Ashford, aed 28, unmarried, managed the household.

The document also listed 37 enslaved people by first name only, their ages, and assigned duties.

One entry caught Rebecca’s eye.

Sarah, age 26, house servant, ladies maid.

Rebecca’s pulse quickened.

Two women similar ages, one the plantation owner’s daughter won her personal maid.

She returned to the photograph, studying their faces with fresh perspective.

She found more documents.

Letters from Elizabeth to a cousin in Virginia, preserved in a family collection donated to the historical society decades ago.

The letters were formal, discussing weather and social calls.

But one from August 1863 included an unusual passage.

The weight of what I know grows heavier each day.

Father’s sins are not mine, yet I inherit their consequences.

I have made a decision that would horrify our society, but my conscience permits no other course.

Well, what decision? What sins? Rebecca discovered Richard Ashford’s will, written in 1857.

Among the property and assets, there was a curious provision.

Upon my death, the girl Sarah is to be granted special consideration in her placement or sale, as her circumstances warrant particular discretion.

The phrasing was odd.

Special consideration, and circumstances suggested something beyond the typical master slave relationship.

Rebecca began searching for Richard Ashford’s personal history.

She found his marriage record from 1834, birth records for Elizabeth in 1835.

But she also found something else.

estate documents from 1831, showing Richard had purchased a woman named Hannah, age 19, who was listed as mulatto, housrained, literate, Hannah.

Rebecca checked the 1864 inventory again.

No Hannah listed.

She found the answer in burial records.

Hannah had died in 1847.

Cause of death listed as fever.

S, but in the same year’s property records, there was a birth registered on the Asheford plantation.

A girl named Sarah, born to Hannah in January 1837.

Rebecca did the math.

Sarah would have been 26 in 1863, the same age as the woman listed in the household inventory.

Born just 2 years after Elizabeth.

The implications were staggering, but Rebecca needed proof, not just circumstantial evidence.

Rebecca knew she needed more than property records and inventories.

She needed Sarah’s voice, something that proved Sarah was more than just a name in a ledger.

But enslaved people rarely left written records.

Their stories were systematically erased by a system that denied their humanity.

She spent three days searching through every document related to the Asheford household.

Then, in a collection of papers donated by a distant Asheford relative in 1923, she found a small leather journal.

The handwriting was cramped and uncertain, as if the writer feared being discovered.

The first entry was dated July 1862.

Miss Elizabeth gave me this book.

She says, “I should write my thoughts, though I scarce know what to write.

That would not bring danger.

” Rebecca’s hands trembled as she turned the pages.

Here was Sarah’s voice preserved against all odds.

The entries were sporadic, cautious.

Sarah wrote about daily tasks, weather, the sound of distant artillery as Union forces approached Charleston.

But gradually more personal observations emerged.

Miss Elizabeth insists I take lessons with her in the evening.

She teaches me to read better, to write properly.

Master Richard must not know.

If he discovered his books being touched by such as me, his rage would be terrible.

Another entry dated March 1863.

She told me today, set it straight with tears in her eyes.

We share a father, Sarah.

You are my sister, though the world will never acknowledge it.

I knew it in my bones already.

I see his features in my mirror, the same as in hers.

But hearing the words spoken aloud felt like lightning striking.

Rebecca photographed every page, her heart pounding.

This was the confirmation she needed.

Elizabeth and Sarah were halfsisters, connected by their father’s exploitation of an enslaved woman.

But the journal revealed more than just their relationship.

It documented Elizabeth’s growing determination to acknowledge Sarah publicly despite the enormous risk.

She has become reckless with grief and guilt.

Since Master Richard fell ill last month, she speaks openly to me when we are alone.

She says, “When he dies, I will free you.

I will give you money to go north.

But first, I want something to remember you by.

Something that shows the truth of who we are to each other.

” The journal’s final entry was dated September 13th, 1863, one day before the mysterious photography session.

Tomorrow we do the impossible thing.

Miss Elizabeth has arranged it with the photographer, Mr.

Whitmore.

He is sympathetic to our cause.

We will sit together dressed as equals and have our portrait made.

She says, “Let there be one true image of us, Sarah.

One moment where the world’s lies cannot touch us.

I’m terrified and thrilled in equal measure.

” Rebecca sat back, overwhelmed by the courage and desperation in those words.

Rebecca needed to understand the full risk Elizabeth and Sarah had taken.

She contacted Dr.

Marcus Williams, a colleague who specialized in Civil War era social customs and legal codes.

They met at a coffee shop near the university.

Rebecca showed him the photograph and explained what she discovered.

Marcus studied the image, then looked up with grave eyes.

“Do you understand what would have happened if they were caught?” “I’m beginning to,” Rebecca said.

In 1863, Charleston, Marcus explained, “What Elizabeth did was social suicide at minimum, possibly criminal.

South Carolina’s slave codes explicitly forbade treating enslaved people as equals.

The law stated that slaves must show deference at all times, walking behind white people, not making eye contact, certainly never sitting beside them as equals.

” He pointed to the photograph.

“This image violates every social and legal norm of Confederate society.

If discovered, Sarah could have been whipped or sold away for insubordination.

Elizabeth would have been ostracized completely.

Her property potentially seized by relatives claiming she was mentally unfit.

And the photographer, Rebecca asked, Whitmore, he could have been arrested for aiding insurrection.

Abolitionist sympathies were dangerous, even suspected ones.

People were tred and feathered for less.

Rebecca showed him Sarah’s journal entry about the sitting.

Marcus read it slowly, then shook his head in amazement.

This wasn’t just a portrait, he said quietly.

This was an act of resistance.

Elizabeth was creating evidence of Sarah’s humanity, of their kinship in a society built on denying both.

Rebecca returned to the archives with new questions.

She searched for records of September 14th, 15, 1863, looking for any indication that the photography session had been discovered.

She found a curious entry in the Charleston police records, a report filed on September 15th about a disturbance near King Street.

The report was vague, mentioning suspicious activity reported at a photography studio, but noting that upon investigation, nothing irregular was found.

Had someone reported seeing two women entering Whitmore’s studio? Had the police come to investigate? Rebecca found another document, a letter from Jonathan Whitmore to his brother in Boston, dated September 20th, 1863.

I took a great risk this week, one that could cost me my business or worse.

But when a young woman comes to you, knowing full well the danger, asking only to have one true image of herself and her sister, a sister the law denies exists, how can one refuse? I have hidden the negative well.

Perhaps someday when this madness ends, the truth it contains will matter.

Whitmore had understood exactly what he was preserving.

But what had happened to that negative, and how had the photograph survived? Rebecca traced the timeline forward from September 1863.

The journal entries stopped after the photography session.

Either Sarah stopped writing or subsequent pages had been lost.

She searched for records of what happened to the Asheford household in the following months.

Richard Ashford’s death certificate showed he died on November 3rd, 1863 of heart failure and complications of illness.

His estate passed to Elizabeth as she was his only legitimate heir.

But what happened next was documented in a probate challenge filed in January 1864.

Distant Ashford cousins contested the will, claiming Elizabeth had been unduly influenced by servants and northern sympathizers and was unfit to manage the estate.

Rebecca found the court testimonies.

Neighbors testified that Elizabeth had been seen treating her house servants with inappropriate familiarity.

A former overseer claimed she had failed to maintain proper discipline.

The cousins won.

The court appointed them as administrators of the estate, stripping Elizabeth of control.

The property inventory from March 1864, listed the forced sale of various household assets, including servants.

Sarah’s name appeared on the sale list.

Sarah, age 27, ladies maid, sold to broker for transport to auction in Montgomery, Alabama.

Rebecca’s throat tightened.

Sarah had been sold away, separated from Elizabeth, sent to the Deep South, where her fate would become even more uncertain.

But what happened to Elizabeth? Rebecca found a notice in the Charleston Mercury from April 1864.

Miss Elizabeth Ashford has departed Charleston for parts unknown.

Her relatives declined to comment on her whereabouts.

She had disappeared.

Rebecca expanded her search beyond Charleston.

She checked records in North Carolina, Virginia, even northern states where refugees often fled.

For 2 weeks, she found nothing.

Then, almost by accident, she discovered a name in a Philadelphia boarding house register from July 1864.

Miss E.

Ashford, lately of South Carolina, in need of respectable employment.

Philadelphia, a Union city, a hub of abolitionist activity.

Elizabeth had fled north.

Rebecca found more records.

A newspaper advertisement from August 1864.

Lady of good breeding offer services as governness or companion.

References available.

Inquire at Mrs.

Thompson’s boarding house, Chestnut Street.

Elizabeth had survived, but at tremendous cost.

She’d lost her home, her social position, her fortune, everything except the one thing that had mattered most, her integrity.

But what about Sarah? Rebecca’s search for Sarah’s fate became obsessive.

She scoured records from Montgomery, checking auction lists and bills of sale, looking for any trace of a woman matching Sarah’s description.

The war ended in 1865.

Enslaved people were freed.

But the chaos of reconstruction meant records were scattered and incomplete.

Rebecca was beginning to fear she’d never find Sarah again.

Rebecca’s breakthrough came from an unexpected source.

While researching abolition networks, she found references to a Quaker family in Philadelphia, the Thompsons, who had operated a boarding house that sheltered refugees and former slaves, the same Thompson boarding house where Elizabeth had stayed.

Rebecca contacted the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and requested access to the Thompson family papers.

The collection included letters, account books, and a diary kept by Martha Thompson from 1863 to 1867.

Rebecca’s hands shook as she read the entry from November 1864.

Today, a young woman of color arrived at our door exhausted and desperate.

She had escaped from Alabama, traveled for weeks through dangerous territory, guided by brave conductors on the railroad.

She asked if we knew of an Elizabeth Ashford.

When I confirmed that Elizabeth had stayed with us earlier this year, the woman began to weep with relief.

She says they are sisters.

Sarah had escaped.

She had made her way through unimaginable hardship to Philadelphia, following rumors and whispered names until she found people who could lead her to Elizabeth.

Martha Thompson’s diary continued, “The reunion between Elizabeth and Sarah was the most profound thing I have witnessed in all my years of this work.

They held each other and wept for an hour.

Elizabeth kept saying, “I tried to free you before they took you.

I failed you.

” And Sarah replied, “You freed me in every way that mattered long before I left that place.

” Rebecca discovered that Martha Thompson had helped both women find work.

Elizabeth became a teacher at a school for Freriedman’s children.

Sarah learned dress making and eventually opened her own shop.

More documents emerged.

A marriage record from 1867 showed Sarah had married a freeman named Thomas, a carpenter.

Elizabeth never married, but remained close to Sarah and Thomas, living nearby, frequently mentioned in family letters as Aunt Elizabeth.

Rebecca found photographs from later years.

An image from 1870 showed Sarah, Thomas, and their two young daughters standing in front of their home.

And there, slightly to the side, was Elizabeth, older, grayer, but smiling.

The women had built a life together, a family that honored the truth rather than the lies of the society they’d fled.

But one mystery remained.

What had happened to the original photograph from 1863? How had it survived the chaos of war and made its way into the Charleston archives? Rebecca found the answer in Jonathan Whitmore’s estate documents.

When he died in 1889, his photography studios contents were sold.

The negatives and prints were purchased by a collector named James Morrison, who was assembling a comprehensive archive of Civil War era photography.

Morrison’s collection eventually went to the Charleston Historical Society in 1931.

And there, misfiled and mislabeled as two ladies of Charleston, the photograph had waited nearly 90 years for someone to recognize its true significance.

With the core mystery solved, Rebecca faced a new question.

Should she reveal this story publicly? The photograph and documents proved a powerful narrative of resistance and kinship, but she worried about how descendants might react, if any, existed.

She began searching for living relatives.

Sarah’s marriage to Thomas had produced four children.

Their descendants had spread across the country, building lives and families of their own.

Through genealological databases and careful outreach, Rebecca found Margaret, a retired school teacher living in Brooklyn.

Margaret was Sarah’s great great granddaughter.

They met in a cafe in Brooklyn on a cold Saturday in November 2019.

Rebecca brought her laptop loaded with all the documents and photographs she’d discovered.

“My grandmother told stories,” Margaret said, stirring her coffee slowly.

“She said our family came from Charleston, that we had roots there going back before the Civil War.

She mentioned a woman named Sarah who’d escaped slavery and made it to Philadelphia, but the details were vague, passed down through generations like whispers.

” Rebecca opened her laptop and showed Margaret the 1863 photograph.

Margaret stared at the screen, her eyes filling with tears.

“That’s her? That’s Sarah?” Yes, Rebecca said gently, and the woman next to her is Elizabeth, her halfsister.

Rebecca spent the next hour walking Margaret through the evidence, the property records, Sarah’s journal, Martha Thompson’s diary, the later photographs showing the two women’s continued relationship.

Margaret wiped her eyes.

My whole life, I heard stories about a white woman who helped our family, someone who was there in Philadelphia when Sarah arrived.

But I always thought it was just someone kind, you know.

I never imagined it was her sister.

Elizabeth gave up everything, Rebecca said.

Her home, her inheritance, her social standing, she chose Sarah over all of it.

And Sarah escaped slavery to find her, Margaret added, her voice full of wonder.

After being sold away, after everything, she still searched for Elizabeth.

They sat in silence for a moment to the weight of the story settling between them.

“What happens now?” Margaret asked.

“That’s your decision,” Rebecca said.

“This is your family’s history.

I can write the academic paper, share the research in scholarly circles.

But if you want this story told more widely to honor both Sarah and Elizabeth properly, I’ll help you do that.

Margaret looked at the photograph again, studying the faces of the two women who had defied everything their world demanded.

Tell their story, she said firmly.

Tell it completely.

They risked everything to have this one honest image.

The least we can do is make sure people understand what they did.

Rebecca published her findings in the Journal of Civil War history in February 2020.

The article titled Sisterhood Defiant: Kinship, Resistance, and Photography in 1863 Charleston detailed the complete story of Elizabeth and Sarah.

The response was immediate and overwhelming.

News outlets picked up the story.

The photograph went viral on social media, shared millions of times with captions expressing amazement, anger at the system that had denied their relationship, and admiration for their courage.

But the deeper impact came from historians and descendants of other enslaved families.

Rebecca received dozens of emails from people saying, “Could you help me research my family’s story?” The photograph had opened a door, making people realize that similar stories might be hidden in archives everywhere.

The Charleston Historical Society organized a special exhibition titled Hidden Kinship: The Ashford Sisters.

Rebecca worked with Margaret and other descendants to curate the display, which included the original photograph, Sarah’s journal, Martha Thompson’s diary entries, and later images of the Reunited family in Philadelphia.

At the exhibition’s opening in August 2020, Margaret stood before a crowd of over 200 people.

Rebecca had offered to speak, but Margaret insisted on doing it herself.

Sarah and Elizabeth lived in a world that told them their relationship was impossible.

Margaret began, her voice steady and clear.

The law said Sarah wasn’t even fully human.

Society said Elizabeth should feel nothing but superiority, but they refused those lies.

She gestured to the 1863 photograph, enlarged and displayed prominently on the wall.

This picture wasn’t just a portrait.

It was an act of revolution.

They sat as equals, as sisters, in a world that would have punished them terribly for that simple truth.

They risked everything for one honest moment.

Margaret paused, looking around the room.

And you know what? They won.

Because here we are more than 150 years later and their truth is the thing that survived.

All the laws that said Sarah was property gone.

All the social rules that said Elizabeth should despise her forgotten.

But this image of two sisters sitting together in dignity and love, that’s eternal.

The applause was thunderous.

Afterward, people lined up to speak with Margaret, many in tears.

A woman in her 70s approached with a faded photograph of her own.

“This is my great-grandmother,” she said.

“She was enslaved in Virginia.

I have so many questions about her life, but I never knew where to start looking.

Rebecca and Margaret exchanged glances.

This was just the beginning.

In the months following the exhibition, the impact of Elizabeth and Sarah’s story continued to ripple outward.

The Charleston Historical Society created a new research initiative focused on identifying enslaved individuals in their photograph collections, many of whom had been cataloged simply as servants or attendants.

Rebecca received a research grant to continue documenting stories of kinship across the color line during the slavery era.

She partnered with genealogologists in descendant communities, helping families piece together histories that had been deliberately obscured.

Margaret became an advocate for genealogical justice, speaking at universities and historical societies about the importance of centering descendants voices in historical research.

She worked with DNA testing companies to help connect African-American families with ancestral roots, filling in gaps that slavery’s recordkeeping had created.

The original 1863 photograph was digitally restored and made freely available online.

It was used in textbooks, documentaries, and museum exhibitions across the country, not just as evidence of slavery’s cruelty, but as proof of resistance and love.

In June 2021, Margaret received an unexpected email from a woman named Caroline, who had seen the exhibition coverage online.

Caroline was descended from Elizabeth’s cousin, the very relatives who had seized the Ashford estate in 1864.

I am ashamed of what my ancestors did, Caroline wrote.

They destroyed Elizabeth’s life out of greed and prejudice.

I can’t change the past, but I want you to know that I honor what Elizabeth and Sarah did.

Their courage shames my family’s cowardice.

Margaret and Caroline met in Charleston, walking the streets where Elizabeth and Sarah had once lived.

They visited the site where Whitmore’s photography studio had stood.

They found the church where Richard Ashford was buried and nearby they discovered Hannah’s unmarked grave in the section reserved for enslaved people.

Together they arranged for a proper headstone.

Hannah sat 1812 1847 mother of Sarah beloved.

On the afternoon of their visit, Margaret and Rebecca returned one final time to the historical society.

They stood before the photograph looking at the two women whose defiant choice had changed so many lives.

“What do you think they would say?” Margaret asked quietly.

if they knew we were here telling their story.

Rebecca considered the question.

She thought of Sarah’s journal entry, of Elizabeth’s letters, of the reunion in Philadelphia, of the life they’d built together against all odds.

I think, Rebecca said finally, they’d say it was worth it.

Every risk, every sacrifice, because the truth survived.

Love survived.

Margaret nodded, reaching out to touch the glass protecting the photograph.

And we survived.

We are still here, still telling the story.

That’s their victory.

As they left the building, the late afternoon sun cast long shadows across Charleston’s historic streets.

Somewhere in those shadows, Rebecca imagined, the spirits of two sisters walked together, free at last, acknowledged at last, remembered as they’d always deserved to be, not as mistress and slave, but as family.

The photograph remained a silent witness to their courage, waiting for the next person who would look closely enough to see the truth it held.

News

Pope Leo XIV SILENCES Cardinal Burke After He REVEALED This About FATIMA—Vatican in CHAOS!

A Showdown in the Vatican: Cardinal Burke Confronts Pope Leo XIV Over Fatima Revelations In a dramatic turn of events…

ARROGANT REPORTER TRIES TO HUMILIATE BISHOP BARRON ON LIVE TV — HIS RESPONSE LEAVES EVERYONE STUNNED When a Smug Question Turns Into a Public Trap, How Did One Calm Answer Flip the Entire Studio Against Its Own Host? A Live Broadcast, a Loaded Accusation, and a Moment of Brilliant Composure Now Has Millions Replaying the Exchange — Click the Article Link in the Comment to Watch the Scene Everyone Is Talking About.

Bishop Barron Confronts Hostile Journalist in a Live TV Showdown In a gripping encounter that captivated audiences, Bishop Robert Barron…

Angry Protesters Disrupt Bishop Barron’s Mass… His Response Moves Everyone to Tears

A Transformative Encounter: Bishop Barron’s Unforgettable Sunday Mass What began as an ordinary Sunday Mass at the cathedral took an…

Bishop Barron demands Pope Leo XIV’s resignation in fiery speech — world leaders respond

A Historic Confrontation: Bishop Barron Calls for Pope Leo XIV’s Resignation In an unprecedented turn of events, the Vatican finds…

Pope Francis leaves a letter to Pope Leo XIV before dying… and what’s written in it makes him cry.

The Emotional Legacy of Pope Francis: A Letter to Pope Leo XIV In a poignant moment of transition within the…

POPE LEO XIV BANS THESE 12 TEACHINGS — THE CHURCH WILL NEVER BE THE SAME AFTER THIS When Ancient Doctrine Is Suddenly Silenced, What Hidden Battle Is Tearing Through the Heart of the Vatican — and Why Are Believers Around the World Being Kept in the Dark? Secret decrees, quiet councils, and forbidden teachings now threaten to rewrite centuries of faith — Click the Article Link in the Comment to Discover What the Church Isn’t Saying.

Pope Leo XIV Challenges Tradition with Bold Ban on Twelve Teachings The Catholic Church stands on the brink of transformation…

End of content

No more pages to load