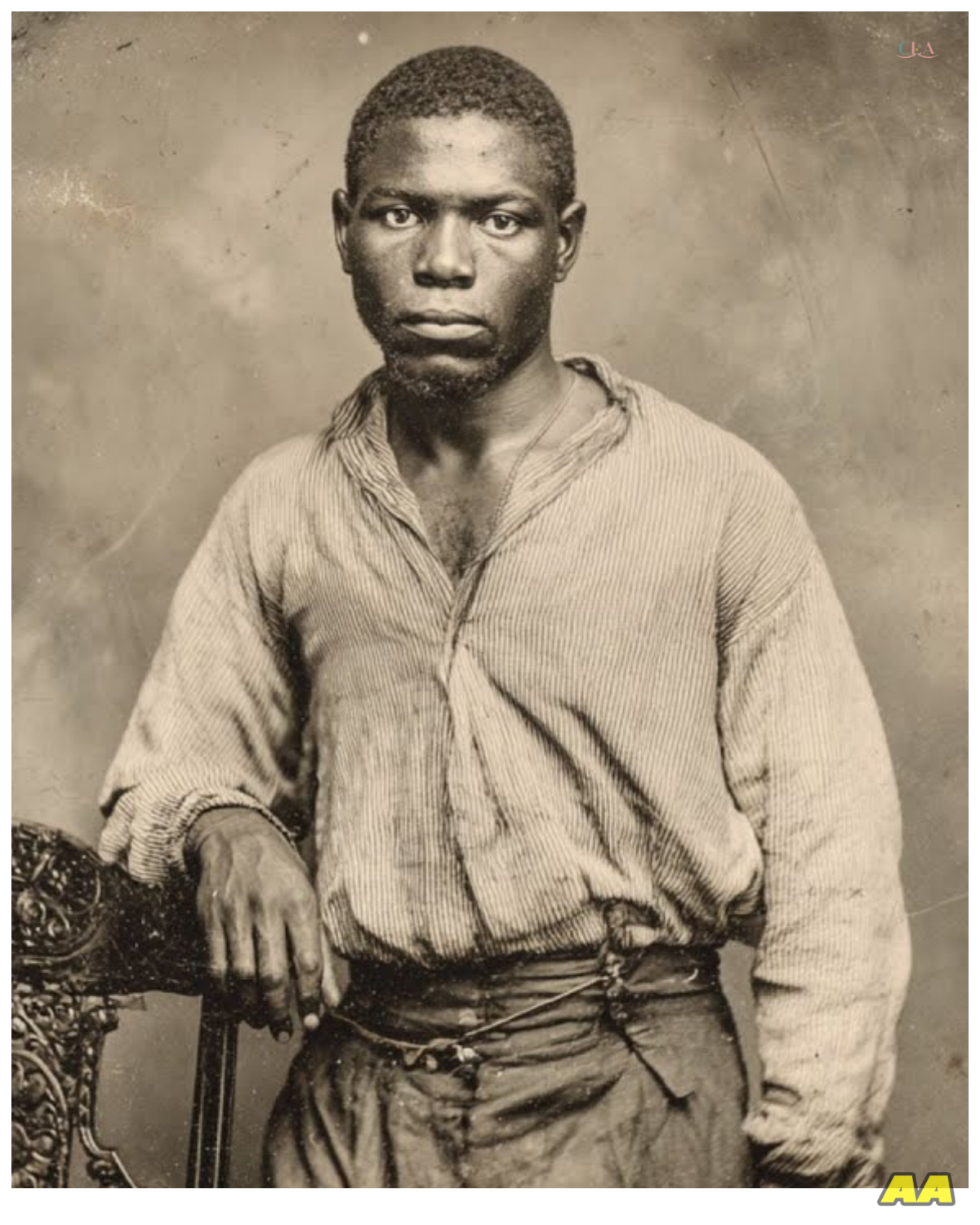

This 1861 Photo Looked Peaceful — Until They Saw What the Slave Was Forced to Hold

Welcome to this journey through one of the most disturbing cases recorded in Montgomery, Alabama’s history.

Before we begin, I invite you to leave in the comments where you’re watching from and the exact time you’re listening to this narration.

We’re interested in knowing which places and what times of day or night these documented accounts reach.

In the year 1861, a photograph was taken on the Freeman plantation just outside Montgomery, Alabama.

To the casual observer, it appeared to be nothing more than another formal portrait of the Antibbellum South, a documentation of property and prosperity.

The image showed a gras image sat in a collection of Civil War era photographs, unremarkable among thousands, cataloging the period before America tore itself apart.

What no one noticed, or perhaps chose not to see until the photograph was examined by archivist Margaret Hamilton in 1963, was what Isaac had been forced to hold in his hands.

The discovery would lead nd white house with columns, several well-dressed individuals, and in the corner, barely visible, a man identified only as Isaac in the photographers’s notes.

For nearly a century, thito one of the most disturbing investigations into the psychological horrors of plantation life ever documented, revealing a pattern of psychological torture that extended far beyond physical brutality.

But by the time the truth emerged, almost everyone connected to the case had long since passed away, leaving only fragments of evidence and whispered stories.

According to county records from 1860, the plantation belonged to Thomas Wilson, a man described in local newspapers as a gentleman of means and considerable influence in Montgomery society.

The documentation suggests Wilson had purchased the property in 1852 after relocating from Virginia, bringing with him 17 enslaved individuals, including a man named Isaac Freeman, though the Freeman surname appears only in later records after emancipation.

The Wilson plantation produced cotton and was considered moderately successful by the standards of the day.

What made it unusual, according to records discovered later, was the remarkably low number of reported escape attempts compared to neighboring properties.

At the time, this was attributed to Wilson’s supposedly humane treatment of those he enslaved.

Local church records even mention Wilson receiving recognition from the Baptist congregation for his Christian management of his household.

This perception would later prove to be horrifically misleading.

The photograph in question was taken in April of 1861 just as Alabama had seceded from the Union and tensions were building toward what would become the Civil War.

According to the photographers’s log book preserved in the Alabama Historical Society archives, the session was commissioned by Wilson to commemorate the engagement of his daughter Elellanena to James Caldwell, the son of another prominent local family.

The photographer Frederick Sullivan noted charging Wilson $25 for a series of portraits, including several of the house, the family, and what he described as property inventory images.

The last set of photographs remained in Sullivan’s private collection until his death in 192.

His estate donated the images to the Alabama Historical Society, where they were cataloged, but largely ignored for decades until Margaret Hamilton noticed something peculiar about one particular image while preparing materials for a Civil War centennial exhibit in 1963.

In her notes, Hamilton wrote, “Upon closer examination of photograph labeled Wilson Plantation, April 1861.

I observed that the enslaved man standing at the edge of the frame appears to be holding something unusual in his hands.

Initial inspection suggested it might be farm implements, but magnification reveals what appears to be human remains, possibly preserved fingers.

I have contacted Professor William Jenkins at the university for further analysis.

This brief note would spark an investigation that revealed a system of psychological control so disturbing that several researchers reportedly abandoned the project.

Professor Jenkins, an anthropologist specializing in the cultural history of the deep south, took up the case with his graduate assistant, Thomas Marx.

Their findings compiled in a 60-page report filed in the university archives in 1965 painted a picture of calculated psychological terror disguised behind a veneer of southern gentility.

According to Jenkins report, what Isaac Freeman had been holding in the photograph were indeed human remains, specifically preserved human fingers suspended in a small glass jar.

But whose fingers they were and why Freeman was forced to hold them required deeper investigation.

Jenkins and Markx spent nearly 2 years piecing together the story, interviewing elderly residents of Montgomery who had heard stories passed down through generations, examining county records, and reviewing personal correspondents preserved in various family collections.

The most valuable discovery came in the form of a journal belonging to Elellanena Wilson, Thomas Wilson’s daughter, found in the attic of her granddaughter’s home in Birmingham.

The journal covering the years 1860 through 1863 contains several disturbing entries about life on the plantation and her father’s methods of maintaining order.

An entry dated January 12th, 1861 read, “Father explained his philosophy to Mr.

Caldwell today regarding management of the property.

James seemed impressed, though somewhat disturbed, by Father’s demonstration with Isaac.

Father insisted it was necessary to maintain order without resorting to common brutality.

The mind, he said, is more easily subdued than the body, and with more lasting effect.

” I confess I removed myself from the room when he brought out the jar.

Further investigation revealed that Thomas Wilson had developed what he considered an enlightened approach to preventing escape attempts and resistance among those he enslaved.

Rather than relying solely on physical punishment, which he considered inefficient and damaging to his property’s value, Wilson had created a psychological system of control based on what Jenkins termed ritualized terror.

County medical records showed that Wilson had studied medicine briefly at the University of Virginia before abandoning the profession to manage his family’s plantation interests.

This training, however rudimentary, had apparently informed his approach to controlling those he enslaved.

Instead of public whippings, Wilson used medical procedures and psychological manipulation to create an atmosphere of perpetual dread.

According to depositions given by formerly enslaved individuals from neighboring plantations after the Civil War, Wilson had a reputation for being different in his methods.

One account from a man named Samuel Johnson, recorded by Freriedman’s bureau agents in 1867 stated, “Mr.

Wilson didn’t whip much, not like the others, but everybody more scared of him than any other master around.

He’d take people to that room in the back of the big house, and they come out different, sometimes parts missing, and he make the others carry those parts around, keep them close like a warning.

” The room mentioned in multiple accounts was apparently a modified study in the rear of the Wilson plantation house, which Thomas Wilson had converted into what he called his management office.

According to Elellanena’s journal, the room contained medical instruments, anatomical diagrams, and several preserved specimens in glass jars.

It was here that Wilson would conduct what he termed corrections on those who showed signs of resistance or independent thinking.

The most disturbing aspect of Wilson’s system and apparently what was captured in the 1861 photograph was his practice of forcing individuals to carry preserved remains of family members or close associates who had attempted escape or committed other serious infractions against plantation rules.

In Isaac Freeman’s case, Jenkins and Markx discovered through cross-referencing plantation records with church burial documents that the fingers likely belong to his brother Jacob, who had attempted escape in 1859 and died during capture.

According to Elellanena Wilson’s journal entry from November 3rd, 1859, father had Isaac present during the procedure with Jacob.

He says it is essential for the lesson to be witnessed by family.

Isaac will now be responsible for carrying the reminder, which father believes will ensure his compliance better than any overseer could.

The psychological impact of forcing someone to carry preserved remains of a loved one as a constant reminder of the consequences of disobedience represents a particularly cruel form of psychological torture.

What made Wilson’s approach even more insidious was his insistence that this was more humane than traditional methods of physical punishment.

In correspondence with other plantation owners, several of which were preserved in the Caldwell family papers, Wilson advocated for his methods as being both more effective and more aligned with Christian principles of stewardship.

In one letter dated July 18th, 1860, Wilson wrote to James Caldwell’s father, “The modern plantation owner must recognize that maintenance of order through mere physical correction is both inefficient and increasingly looked upon with disfavor by certain elements in society.

My methods preserve the value of property while ensuring compliance through engagement of the mind rather than destruction of the body.

I have not lost a single hand to escape in 3 years, nor suffered any of the productivity losses associated with excessive physical correction.

The photograph that captured Isaac Freeman holding the jar containing his brother’s preserved fingers was apparently intended as a demonstration of Wilson’s methods for the benefit of his future son-in-law.

According to Elellanena’s journal, James Caldwell was being groomed to eventually take over management of the combined Wilson Caldwell properties after his marriage to Elellanena.

The photograph session in April 1861 seems to have been partly arranged to document Wilson’s plantation management approach for Caldwell’s education.

What happened to Isaac Freeman after the photograph was taken? Here the historical record becomes fragmented.

Plantation records show that he remained on the Wilson property until at least 1863.

A notation in the property ledger from February of that year lists him as being assigned to special duty in the main house.

After that, there is no further mention of him in the Wilson documents.

The next reference to Isaac Freeman appears in Freriedman’s Bureau records from 1866, where a man by that name is listed as having registered in Montgomery to receive rations.

The registration notes that he was approximately 40 years old and had visible mutilation of the left hand, three fingers missing.

Whether this mutilation was connected to Wilson’s management practices remains unclear, but the timing and nature of the injury suggest a possible link.

According to oral histories collected by Marks from descendants of formerly enslaved people in the Montgomery area, stories about the Wilson plantation and a man forced to carry death in his hands persisted well into the 20th century.

One account provided by Martha Johnson, aged 87 when interviewed in 1964, recounted what her grandmother had told her about Isaac Freeman.

Grandma Mahar said there was a man who carried his brother’s fingers in a jar everywhere he went.

Massa made him show it to everyone as a warning.

Said that man never spoke above a whisper after that, and would hide his hands whenever anyone looked at him.

carried those fingers until freedom came, then buried them under a tree and left Montgomery, never came back.

The Wilson plantation itself fell into disrepair after the Civil War.

Thomas Wilson, according to county records, died in 1864 of typhoid fever while serving as a medical officer in the Confederate Army.

His daughter Elellanena and her husband James Caldwell attempted to maintain the property after the war, but financial difficulties forced them to sell most of the land by 1870.

The main house burned down in 1873, reportedly due to an unattended kitchen fire, though local rumors suggested arson.

What makes this case particularly disturbing is not just the nature of the psychological torture inflicted on Isaac Freeman and others, but the way in which it was rationalized and even presented as progressive by its perpetrator.

Thomas Wilson appears to have genuinely believed his methods were more humane than conventional physical punishment, and he found support for this view among his social circle.

This perverse logic that sophisticated psychological torture represented moral improvement over physical brutality offers a disturbing glimpse into how systems of oppression can be maintained and justified even by those who consider themselves enlightened.

Professor Jenkins report on the case completed in 1965 was filed with the university but never published.

According to his personal correspondence found among his papers after his death in 1978, he felt the material was too disturbing and potentially traumatizing to make publicly available.

His research assistant, Thomas Marx, apparently disagreed with this decision, arguing that the story needed to be told as part of a complete accounting of plantation era atrocities.

This disagreement led to a permanent rift between the two scholars.

In 1967, Markx attempted to publish an article about the Wilson plantation and the photograph of Isaac Freeman in an academic journal, but it was rejected on grounds that the evidence was too circumstantial and the claims too explosive.

Frustrated by this rejection, Markx reportedly continued his research independently until his death in a car accident in 1969.

His research notes, which supposedly included additional evidence not included in Jenkins original report, were never found.

The photograph itself remained in the Alabama Historical Society archives until 1968 when it was removed from public access at the request of the remaining Wilson Caldwell descendants.

According to archive records, the family threatened legal action if the photograph and its associated research remained available, claiming that Jenkins and Mark’s conclusions were defamatory and based on misinterpreted evidence.

The society, lacking funds for a potential legal battle, complied with the request.

For decades, the case remained essentially buried, known only to a handful of historians specializing in plantation era psychological control methods.

The photograph was reportedly transferred to the National Archives in Washington, D.

C.

in 1972 as part of a larger collection of Civil War era images where it was cataloged without the controversial analysis of its contents.

In 1988, historian Rebecca Collins came across references to the photograph and Jenkins research while working on her doctoral dissertation about psychological control mechanisms on antibbellum plantations.

Her attempts to locate the original photograph and research materials were largely unsuccessful as the Wilson Caldwell family had by then secured a court order sealing many of the relevant documents.

Collins dissertation mentioned the case only briefly, noting that substantial evidence suggests some plantation owners developed sophisticated psychological torture methods involving preserved human remains as control mechanisms, though specific documentation remains inaccessible due to ongoing legal restrictions.

What little we know about Isaac Freeman’s life after emancipation comes from scattered records and oral histories.

The Freriedman’s Bureau documented that he worked briefly as a laborer in Montgomery until approximately 1868, then disappeared from official records.

According to the oral history provided by Martha Johnson, local stories held that Freeman left Alabama entirely, possibly heading north.

One account suggested he eventually settled in Illinois, while another claimed he joined a community of formerly enslaved people in Kansas.

None of these accounts can be verified with certainty.

The last potentially reliable mention of Isaac Freeman appears in the journal of a Methodist minister in Cairo, Illinois, dated 1873.

The entry describes meeting an unusual man missing several fingers who carried a small wooden box he would not be separated from.

When asked about his past, he would only say he came from Alabama and that some burdens cannot be put down, only buried.

Whether this refers to the same Isaac Freeman from the Wilson plantation cannot be confirmed.

The psychological impact of carrying preserved remains of a family member as a form of control represents a particularly insidious form of torture.

Modern psychological analysis suggests such practices would likely produce severe trauma, possibly resulting in conditions similar to what we now recognize as post-traumatic stress disorder.

The constant physical reminder of a loved one’s death, combined with being forced to display that reminder as a warning to others, would create a complex psychological prison potentially more effective than physical restraints.

Thomas Wilson’s system appears to have been unique in its specifics, but it existed within a broader context of psychological control methods used throughout the plantation south.

What distinguished Wilson’s approach was its pseudocientific framework and his explicit rejection of physical punishment in favor of what he considered more sophisticated methods.

This allowed him to maintain an image of refinement and even humanity while inflicting profound psychological damage.

The efforts to suppress the story of Isaac Freeman and the Wilson plantation practices raise important questions about historical memory and accountability.

The successful campaign by the Wilson Caldwell descendants to restrict access to the photograph and associated research represents a pattern of historical erasure that has often characterized attempts to reckon with the darkest aspects of American slavery.

By controlling access to evidence and challenging the credibility of researchers, families and institutions with connections to plantation era atrocities have often managed to keep disturbing histories out of public consciousness.

The photograph of Isaac Freeman holding the jar containing his brother’s preserved fingers remains a haunting document of psychological torture disguised as enlightened management.

The fact that it was intentionally created as a demonstration of Wilson’s methods, a teaching tool for his future son-in-law, adds another layer of horror to the image.

It captures not just a moment of individual suffering, but the calculated system that produced that suffering and the social context that validated it.

In 1960, archaeologists conducting a survey of the former Wilson plantation land before commercial development discovered a small glass jar buried approximately 3 ft deep beneath what would have been the northeast corner of the main house.

The jar contained three preserved human fingers, though years of ground moisture had degraded the preservation fluid.

No DNA testing was conducted as the technology was not yet available and the remains were reeried without extensive documentation.

Whether these were the same remains visible in the 1861 photograph cannot be determined with certainty, though the location and nature of the find suggest a possible connection.

The story of Isaac Freeman and the Wilson plantation represents a case where photographic evidence captured a moment of psychological horror that might otherwise have remained undocumented.

The apparent normaly of the image until one notices what Isaac is holding mirrors the way in which the Wilson plantation’s reputation for humane treatment masked a reality of sophisticated psychological torture.

It reminds us that historical atrocities often occurred not in hidden corners but in plain sight.

Their true nature obscured by social conventions and deliberate misrepresentation.

Today, the land where the Wilson plantation once stood has been developed into a commercial district on the outskirts of Montgomery.

No historical marker acknowledges the property’s past or the suffering that occurred there.

The descendants of Thomas Wilson and James Caldwell reportedly remain influential in Alabama business and politics, though they have distanced themselves from their ancestors plantation activities.

As for the photograph itself, its current location remains uncertain.

Some sources suggest it was permanently removed from the National Archives in 1992 at the request of a government official with connections to the Wilson Caldwell family.

Others claim it remains in the archives, but has been recatategorized in a way that makes it difficult to locate.

Attempts by more recent historians to access the image have been unsuccessful, often met with bureaucratic obstacles or claims that the photograph cannot be located.

The story of Isaac Freeman, forced to carry his brother’s preserved remains as a psychological control mechanism, stands as a testament to the complex and often overlooked methods of control employed during American slavery.

Beyond physical brutality lay systems of psychological manipulation designed to break resistance not through the body but through the mind.

That such sophisticated methods of psychological torture could be presented as progressive improvements by their perpetrators reveals the profound moral distortions that allowed the institution of slavery to persist.

In the absence of the original photograph, we are left with written descriptions, fragmentaryary historical records, and oral histories passed down through generations.

The image of a man holding a jar containing his brother’s preserved fingers, captured for posterity and then systematically suppressed, has itself become a metaphor for the broader historical eraser of slavery’s psychological dimensions.

Like the photograph, these histories exist in the margins, visible only when we choose to look closely enough to see what has always been there.

As one elderly Montgomery resident told Thomas Marks in 1964, “Some things get buried, but nothing really disappears.

The past is always right there beneath our feet, waiting for someone to dig it up again.

” Perhaps the most disturbing aspect of the Wilson Plantation case is how it illuminates the ways in which systems of oppression adapt and evolve, finding new methods of control when old ones become untenable.

Thomas Wilson’s shift from physical punishment to psychological torture precages modern forms of control that operate through the mind rather than the body.

His claim that his methods were more humane echoes, justifications still heard today for sophisticated systems of domination that leave no visible marks.

The photograph of Isaac Freeman standing stiffly at the edge of the frame, forced to hold the physical remains of his brother, captures a moment of historical horror that extends far beyond the borders of the image itself.

It reminds us that sometimes the most important elements of history are found not at the center of the frame, but in the margins where uncomfortable truths often reside.

In the words of Margaret Hamilton, the archivist who first noticed the disturbing detail in the photograph.

History reveals itself in the periphery, in the things we are not meant to notice.

Once seen, they cannot be unseen, and they change everything we thought we knew about the picture as a whole.

The jar containing human fingers may have been buried, the photograph suppressed, and the document sealed, but the story they tell about the psychological dimensions of slavery remains a vital part of American history, a history that continues to shape our present in ways both acknowledged and denied.

Like Isaac Freeman, we all carry the weight of this history, whether we choose to look at what’s in our hands or not.

In 1957, nearly a decade before Jenkins and Markx began their investigation, a woman named Sarah Thompson contacted the Alabama Historical Society claiming to be a descendant of Isaac Freeman.

According to the society’s visitor log, Thompson requested access to any records related to the Wilson plantation, stating that family stories had been passed down about an ancestor who had been subjected to unusual cruelty involving preserved remains.

Her request was apparently denied by the society’s director, who noted in internal correspondence that entertaining such inquiries would only serve to inflame tensions at a time when our state is dealing with enough controversy.

Thompson did not give up easily.

Records from the Montgomery County Courthouse show that she filed a formal request for access to property records related to the Wilson plantation in 1958.

This request was granted, though the records themselves contained little information beyond basic property transactions.

More significantly, she placed an advertisement in the Montgomery advertiser seeking information from anyone whose family had connections to the Wilson plantation.

According to newspaper archives, the advertisement ran for three consecutive Sundays, but generated no public responses.

What Thompson did not know was that her inquiries had attracted attention.

A letter from James Wilson Caldwell III, a prominent Montgomery businessman and direct descendant of Thomas Wilson to the historical society director dated June 10th, 1958, expressed concern about a colored woman asking questions about family matters best left in the past.

The letter suggested that appropriate measures be taken to discourage further investigation.

Thompson’s attempts to uncover her family history coincided with the early years of the civil rights movement in Montgomery.

Just two years earlier, the Montgomery bus boycott had drawn national attention to racial injustice in the city.

In this charged atmosphere, attempts to investigate plantation era atrocities were particularly unwelcome among certain segments of white society.

According to civil rights archives at Alabama State University, several African-American researchers attempting to document plantation histories during this period reported harassment and threats.

What happened to Sarah Thompson after 1958 is unclear.

Her name disappears from public records in Montgomery after that year.

According to an oral history interview conducted in 1977 with civil rights activist Robert Williams, a woman believed to be Thompson relocated to Detroit after receiving anonymous threats.

Williams recalled there was a lady asking about plantation records, something about her greatgrandfather having to carry some terrible thing around.

People didn’t like her asking those questions.

She got some late night calls, decided it wasn’t worth her life.

Last I heard, she’d gone up north.

The connection between Sarah Thompson and Isaac Freeman cannot be verified with absolute certainty, but the timing of her inquiries and the specific nature of the unusual cruelty she mentioned suggest she may indeed have been following a family oral history related to the Wilson plantation practices.

If so, her efforts represent an important attempt to reclaim a history that others were actively working to suppress.

In 1969, the same year Thomas Marx died in his car accident, a fire at the Montgomery County courthouse damaged numerous records from the 1860s, including most of the remaining documentation related to the Wilson plantation.

Official reports attributed the fire to faulty electrical wiring, though rumors persisted that it might have been deliberately set.

The timing, just as Markx was preparing to publish his research, despite academic rejection, struck some observers as suspicious.

Professor Jenkins decision not to publish his findings about the Wilson plantation practices came after several disturbing incidents.

According to his private correspondence with a colleague at Harvard, preserved in that university’s archives, Jenkins received anonymous letters warning him to leave sleeping dogs lie, and remember that some old families still have influence.

More concretely, he learned that his research assistant, Thomas Marx, had been followed by an unidentified vehicle on several occasions while conducting interviews in rural areas outside Montgomery.

In one particularly disturbing letter to his Harvard colleague dated March 3rd, 1965, Jenkins wrote, “I fear T and I may have stumbled upon something with tentacles extending into the present.

Last week my office was broken into, though nothing of value was taken.

The only items disturbed were my research files on the W plantation.

The photograph itself, the one showing the jar, was removed from its folder and left conspicuously on my desk.

This feels like a message, though from whom and to what specific end, I cannot say with certainty.

3 months later, Jenkins abruptly ended his research and submitted his report to the university archives with a restriction limiting access to academic researchers with specific approval.

He accepted a visiting professorship at the University of Chicago for the following academic year and never returned to the topic of plantation psychological control mechanisms in his subsequent work.

His published research shifted to less controversial aspects of southern cultural history.

Thomas Marx, in contrast, became increasingly obsessed with documenting the Wilson case.

After the rejection of his article, he reportedly spent his personal savings traveling throughout the Southeast interviewing elderly African-Ameans whose family histories included connections to the Montgomery area plantations.

According to his sister interviewed in 1970 after his death, Markx believed he was being watched and had taken to carrying a handgun and changing hotels frequently during his research trips.

The car accident that claimed Markx’s life occurred on a rural road outside Selma, Alabama, where he had gone to interview a potential source.

Police reports indicated his vehicle left the road on a straight section of highway with no adverse weather conditions.

No other vehicles were involved.

The investigating officer noted that the accident was consistent with the driver falling asleep or becoming otherwise incapacitated.

Though no medical issues were documented, Marx’s research materials, which he typically carried in a locked briefcase, were not found in the vehicle.

The story of the Wilson plantation photograph emerged briefly into public consciousness in 1971 when journalist Caroline Reed mentioned it in an article about suppressed historical research for the Atlantic.

Reed’s article entitled The Histories We Cannot Tell used Jenkins and Mark’s thwarted research as one example of how powerful interests could effectively control historical narratives.

The article prompted a liel threat from the Wilson Caldwell family and The Atlantic published a partial retraction in a subsequent issue stating that certain unverified allegations regarding historical plantation practices should have been presented with more explicit qualification.

In the decades that followed, the story of Isaac Freeman and the Wilson plantation practices became something of a scholarly urban legend known to many historians of the Antibbellum South, but rarely discussed in formal academic contexts.

Occasional references appeared in specialized publications, usually heavily qualified and without mentioning specific names or locations.

The archaeological discovery of the glass jar containing preserved fingers in 1960 should have provided physical evidence supporting the account derived from the photograph and documentary sources.

However, the limited documentation of this find and the decision to reberry the remains without thorough analysis reflects the common practice of the era when archaeological ethics regarding human remains were less developed than today’s standards.

According to the brief report filed by the archaeological team, the jar was found during routine trenching for a soil survey and its contents were noted but not photographed before rearial.

One member of that archaeological team, Daniel Peterson, later became a prominent archaeologist specializing in plantation sites.

In a 1987 interview for an oral history project on the development of historical archaeology in the South, Peterson mentioned the jar discovery.

There were things we found that never made it into official reports.

The political climate wasn’t right, especially when it involved prominent families still active in local business and politics.

That jar we found at the Wilson site.

I’ve often wondered if we should have done more to document it properly, but at the time the developer was pushing to complete the survey, and there was pressure not to delay the project over what could be dismissed as unpleasant curiosities.

The commercial development that eventually replaced the Wilson Plantation became the Eastale Mall, opened in 1977.

Nothing in the mall’s design or promotional materials acknowledges the history of the land on which it stands.

According to local historians, this erasure of plantation histories is common throughout the South, where commercial developments rarely reference the slaverybased economies that once occupied the same spaces.

In 1992, historian James Washington attempted to locate the Wilson plantation photograph as part of research for a comprehensive study of psychological control methods used against enslaved people.

His requests to the National Archives were initially met with bureaucratic delays.

After persistent inquiries, Washington received a response stating that the photograph could not be located in their collections despite catalog records indicating its transfer there in 1972.

Washington’s subsequent Freedom of Information Act request yielded an internal memo suggesting the photograph had been removed for conservation assessment in 1985, but never returned to the collection.

The conservation department had no record of receiving the item.

Washington’s experience was documented in his 1994 article, Disappearing Evidence: The Challenges of Researching Plantation Atrocities in the Journal of African-Amean History.

In 2004, digital humanities researcher Marcus Reynolds created a detailed reconstruction of the Wilson plantation photograph based on written descriptions and similar contemporary images.

This digital approximation, while not a replacement for the original evidence, attempted to visualize what Margaret Hamilton and others had described seeing.

Reynolds reconstruction showed a formal plantation scene with a black man positioned at the edge of the frame holding what appeared to be a small glass jar containing indistinct pale objects.

Reynolds presented this reconstruction at a digital humanities conference but decided against making it widely available online after consulting with ethics specialists.

As he explained in his conference paper, creating visual representations of historical trauma raises significant ethical questions, particularly when the subjects were denied agency and dignity in the original context.

While this reconstruction aims to recover suppressed history, it risks reproducing the very objectification it seeks to critique.

The Wilson Caldwell family’s efforts to control access to the photograph and associated research materials represent a common pattern in how wealthy and influential families have managed potentially damaging historical revelations.

Similar cases have been documented throughout the South where descendants of plantation owners have used legal threats, political connections, and philanthropic relationships with cultural institutions to limit access to materials that might tarnish family legacies.

What makes the Wilson case particularly significant is how it illuminates psychological torture methods that left few physical traces and were thus easier to erase from historical memory.

The absence of obvious physical brutality allowed Thomas Wilson to maintain a reputation for humane treatment, a reputation that his descendants could later cite when challenging researchers findings.

The sophisticated nature of his psychological control system with its pseudocientific veneer also made it easier to dismiss accounts as exaggerated or misinterpreted.

In 2012, a breakthrough in the case came from an unexpected source.

During renovation of a historic home in Montgomery that had once belonged to Frederick Sullivan, the photographer who took the 1861 image, workers discovered a hidden compartment in an upstairs wall containing a metal box.

Inside were several glass plate negatives wrapped in cloth along with a journal.

The home’s owner, unaware of the potential significance, contacted the Alabama Department of Archives and History.

Archavists quickly identified the negatives as Sullivan’s work, including several images from the Wilson plantation session.

The journal contained Sullivan’s private thoughts about his photographic commissions, including disturbing observations about the Wilson property.

An entry dated April 12th, 1861 read, “Completed the Wilson Commission today.

most unusual request I have yet received.

Mr.

Yablau insisted on photograph of the negro Isaac holding the specimen jar, said it was important to document his management methods for his future son-in-law.

I found the practice disturbing, but am in no position to refuse the business.

The negro man’s expression haunts me, complete emptiness in the eyes, as though looking at nothing at all.

I shall not include this image in the formal delivery, but will retain the negative for my own records.

This journal entry provided important corroboration of the photograph’s existence and purpose.

It confirmed that the image was deliberately created to document Wilson’s management methods and that the photographer himself found the practice disturbing.

Perhaps most significantly, it explained why the photograph had not been included in the formal portrait series delivered to the Wilson family, instead remaining in Sullivan’s private collection until his death.

The discovery prompted renewed interest in the Wilson plantation case.

Historians Dana Mitchell and Robert Carter secured funding for a comprehensive investigation, including attempts to locate any surviving descendants of Isaac Freeman who might have family stories or documents related to the case.

Their search led them to Chicago where they identified three individuals with genealogical connections to Isaac Freeman.

One of them, Elijah Freeman, possessed a family Bible with handwritten entries dating back to 1870.

The Bible contained a pressed flower and a small envelope.

Inside the envelope was a handwritten note that read, “From the tree where the burden was laid to rest, never forget, never return.

” The note was signed simply if and dated August 12th, 1866.

According to family oral history shared by Elijah Freeman, his ancestor Isaac had escaped psychological captivity by burying something under a tree before leaving Alabama forever.

The family story held that Isaac had been forced to carry death in his hands as punishment for his brother’s attempt to escape.

After emancipation, Isaac had buried his brother’s remains and vowed never to return to Alabama.

He had traveled north, eventually settling in Illinois, where he lived until his death in 1902.

Throughout his life, he reportedly refused to have his photograph taken and would hide his hands whenever strangers were present.

The pressed flower from the family bible was examined by botonists and identified as kirkus negra or water oak, a species common throughout Alabama.

This botanical evidence, while circumstantial, provided a tangible connection to the story of Isaac burying his brother’s remains under a tree before leaving the state.

In 2015, Mitchell and Carter published their findings in a comprehensive book entitled The Burden: Psychological Control and Resistance on the Wilson Plantation.

The book included reproductions of Sullivan’s journal entries, photographs of the Freeman Family Bible, and extensive analysis of the psychological control methods employed by Thomas Wilson.

The Wilson Caldwell descendants, now less prominent in Montgomery society than in previous generations, did not pursue legal action against the publication.

The book prompted discussion about how stories of psychological torture during slavery have been systematically excluded from mainstream historical narratives.

As Mitchell noted in an interview, physical brutality against enslaved people has been documented.

however, incompletely in our historical record.

But the sophisticated psychological torture methods used by someone like Thomas Wilson leave fewer obvious traces and are easier to erase from collective memory.

These are the histories that powerful interests have been most successful at suppressing precisely because they challenge comforting narratives about the nature of oppression and resistance.

The story of Isaac Freeman, forced to carry his brother’s preserved remains as a psychological control mechanism, offers important insights into the complex dynamics of resistance and survival under slavery.

That Isaac eventually buried the jar and left Alabama represents an act of reclamation and resistance, even if delayed by years of psychological captivity.

The fact that his descendants preserved the memory of this act, passing it down through generations despite its traumatic nature, speaks to the importance of family oral histories in maintaining truths that official records often exclude.

Today, a small memorial plaque stands in a quiet corner of the Eastale Mall parking lot, placed there in 2018 after community activists petitioned the mall management.

The plaque reads simply, “This land was once the Wilson plantation.

We remember those who suffered here and honor their humanity, dignity, and resistance.

” The plaque makes no specific mention of Isaac Freeman or the psychological torture methods documented in the 1861 photograph, but its presence represents a small acknowledgement of histories long suppressed.

The jar that Isaac Freeman was forced to hold in that photograph containing his brother’s preserved fingers embodied the perverse logic of slavery’s psychological dimensions.

It transformed a family bond into an instrument of control, weaponizing love and connection to enforce submission.

that Thomas Wilson considered this humane compared to physical punishment reveals the moral distortions that allowed the institution to persist.

The jar became both the method of Isaac’s captivity and eventually the focus of his act of reclamation when he finally buried it under the water oak tree.

In his final years, according to family accounts shared with Mitchell and Carter, Isaac Freeman refused to speak about his time on the Wilson plantation.

The only exception came on his deathbed when he reportedly told his son, “I carried him with me until I could lay him properly to rest.

Then I carried the memory so no one would forget.

Now you must carry it, but only as a memory, never as a chain.

This instruction to carry the memory but not the chain encapsulates the complex relationship between remembrance and trauma that characterizes much of African-American engagement with slavery’s psychological legacy.

To remember is necessary for dignity and truth.

But to be defined solely by that memory risks perpetuating the psychological control mechanisms established during slavery.

Perhaps the most significant aspect of Isaac Freeman’s story is not what was done to him, but what he ultimately did in response.

After years of being forced to carry his brother’s remains as a mechanism of control, he transformed that same act into one of reclamation and proper burial.

By choosing when and where to finally lay his brother to rest, he reasserted agency over a situation designed specifically to deny him any control.

The photograph that captured Isaac holding the jar in 1861 was intended as documentation of his subjugation.

That the image was later suppressed speaks to the power of even visual evidence to be controlled by those with the resources and motivation to do so.

But the story the photograph told of psychological sophistication in systems of control and the resistance such systems eventually generate could not be entirely erased despite decades of active suppression.

As we consider the Wilson plantation case today, we are reminded that historical memory itself is contested territory.

What we remember, what we forget, and what we never learned in the first place shapes our understanding of both past and present.

The story of Isaac Freeman forced to hold his brother’s remains and then choosing to bury them on his own terms reminds us that even in the most carefully controlled systems, human dignity and the drive toward freedom find expression.

In the words that Mitchell and Carter chose to close their book, the jar that Thomas Wilson created as an instrument of control became, in Isaac Freeman’s hands, something else entirely, a burden carried until it could be transformed through the simple, profound act of burial.

In this transformation lies a truth about human resistance that no system, however sophisticated, has ever fully conquered.

The Wilson plantation photograph showing Isaac Freeman holding the jar containing his brother’s preserved fingers remains officially lost, removed from archives, suppressed from public view, and excluded from mainstream historical narratives.

But the story it tells continues to emerge through fragments of evidence, family oral histories, and the persistent work of researchers unwilling to accept historical erasure.

Like the jar itself, finally buried under a water oak tree in Alabama soil, some truths may be temporarily hidden, but are never truly gone.

They remain waiting to be recognized, acknowledged, and ultimately reckoned with by future generations seeking a more complete understanding of our shared Past.

News

✈️ U.S. F-15 FIRST STRIKE — ALLEGED CARTEL DRUG LAB ERASED IN SECONDS AS SKY ERUPTS IN A BLINDING FLASH ✈️ What officials described as a precision operation turned the night into daylight, with jets screaming overhead and a suspected production site reduced to smoking rubble in moments, sending a shockwave across the region and a message that the airspace above is no safe haven for hidden empires 👇

The Last Fortress: A Shocking Revelation In the heart of the Mexican jungle, Diego stood at the entrance of the…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: FBI & ICE SHATTER ALLEGED TRUCKING NETWORK WITH SOMALI TIES — 83 ARRESTED, $85M IN CASH AND WEAPONS STACKED AS EVIDENCE 🚨 Before sunrise, federal agents swept through depots and dispatch offices, hauling out duffel bags of currency and seizing firearms while stunned neighbors watched a logistics operation authorities claim was hiding a sprawling criminal enterprise behind everyday freight routes 👇

The Shadows of the Ghost Fleet In the heart of the Midwest, where the snow fell like a blanket over…

🚨 FBI & ICE STORM GEORGIA “CARTEL HIDEOUT” — GRENADE LAUNCHER DISCOVERED AND $900K IN DRUGS SEIZED IN A DAWN RAID THAT SHOCKED THE BLOCK 🚨 What neighbors thought was just another quiet morning exploded into flashing lights and tactical vests as agents swept the property, hauling out weapons and evidence while officials described a months-long investigation that culminated in a swift, coordinated takedown 👇

The Unraveling of Shadows: A Tale of Betrayal and Redemption In the heart of Jackson County, Georgia, the air was…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: DEA & FBI CRUSH ALLEGED CARTEL TRUCKING EMPIRE — HIDDEN ROUTES MAPPED, DRIVERS DETAINED, AND MILLIONS STACKED AS EVIDENCE 🚨 Before sunrise, highways turned into a grid of flashing lights as agents intercepted rigs, cracked open trailers, and traced coded dispatch logs, revealing what officials describe as a logistics web hiding in plain sight behind ordinary freight lanes 👇

The Fall of Shadows: A Cartel’s Empire Exposed In the dimly lit corridors of power, where shadows danced with deceit,…

🚢 U.S. NAVY TRAPS SINALOA CARTEL’S ALLEGED $473 MILLION “DRUG ARMADA” AT SEA — AND THE HIGH-STAKES STANDOFF UNFOLDS UNDER FLOODLIGHTS AND ROTOR WASH 🚢 Radar screens lit up, cutters boxed in fast boats, and boarding teams moved with clockwork precision as authorities described a sweeping maritime interdiction that turned open water into a chessboard, stacking seized cargo on deck while prosecutors hinted the ripples would travel far beyond the horizon 👇

The Abyss of Deceit: A Naval Reckoning In the heart of the Caribbean, where the turquoise waters glimmered under the…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: DEA & FBI DESCEND ON MASSIVE TEXAS LOGISTICS HUB — 52 TONS OF METH SEIZED AS 20 POLITICIANS ALLEGEDLY TIED TO A SHADOW NETWORK ARE THRUST INTO THE SPOTLIGHT 🚨 What began as a quiet federal probe detonated into a sweeping raid of warehouses and boardrooms, with agents hauling out towering stacks of evidence while stunned insiders whisper that the real shockwave isn’t just the drugs — it’s the powerful names now facing intense scrutiny 👇

Shadows of the Underground: The Texas Cartel Unveiled In the heart of Texas, where the sun sets over sprawling landscapes,…

End of content

No more pages to load