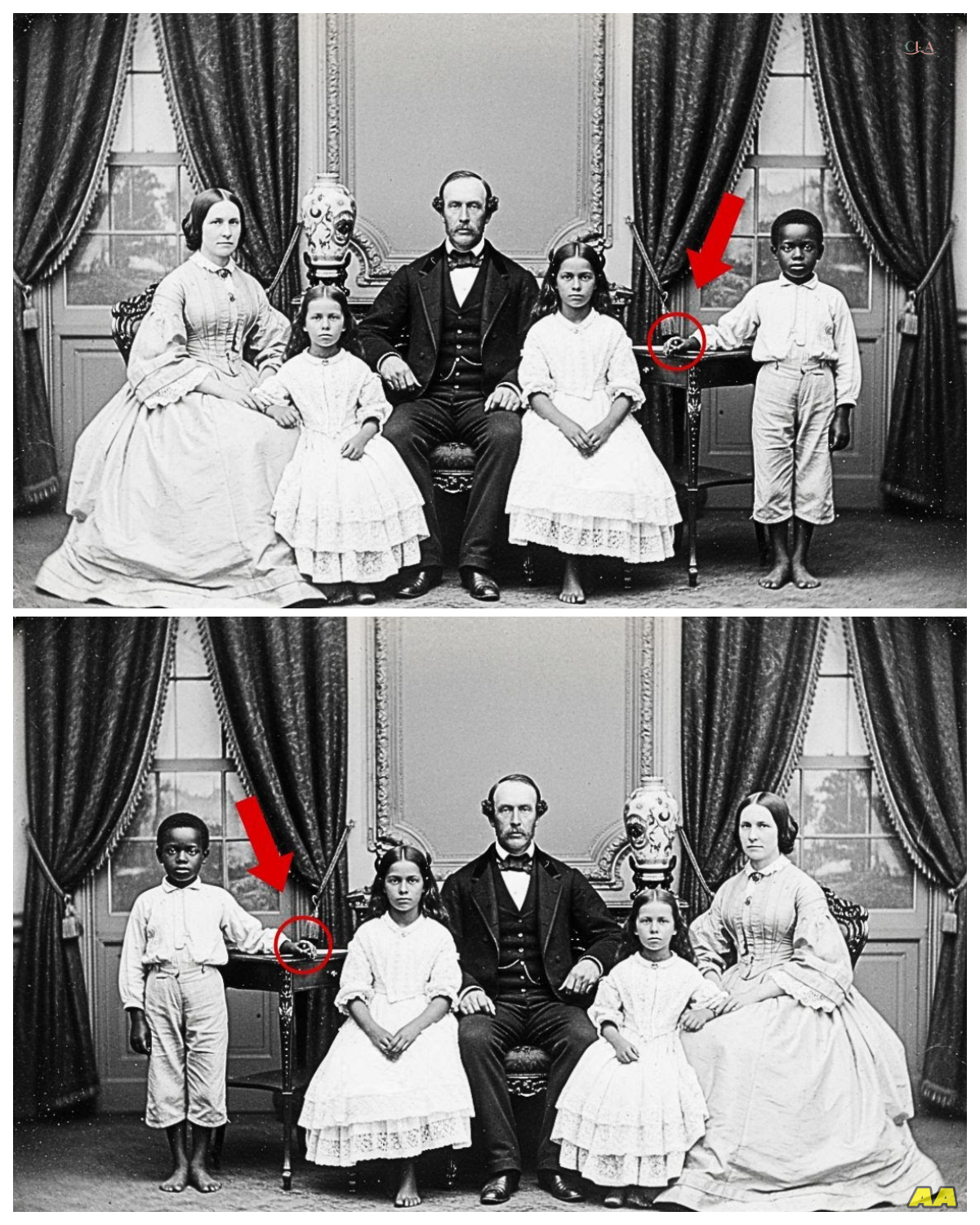

This 1856 Portrait Looked Peaceful — Until Historians Saw What the Enslaved Child Held in His Hands

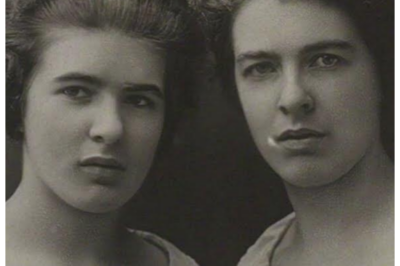

This 1856 portrait looked peaceful until historians saw what the enslaved child held in his hands.

Dr.James Crawford adjusted his reading glasses as he examined a dgerotype at the Library of Congress in Washington DC.

It was February 2024 and he’d been cataloging antibbellum photographic collections for 8 months.

Most images blurred together, stiff poses, formal attire, faces frozen in time by the limitations of early photography.

But this dgeraype stopped him cold.

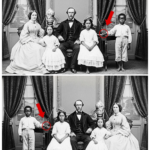

The image dated September 1856 showed the Caldwell family of Richmond, Virginia.

Mr.Thomas Caldwell stood beside his wife Ellaner, both dressed in their finest.

Their two daughters, approximately 10 and 12 years old, wore elaborate white dresses with lace collars.

The interior setting was opulent, heavy velvet curtains, ornate wallpaper, polished mahogany furniture visible in the background.

To the right of the family group stood a young black boy, perhaps seven or eight years old.

He wore simple cotton clothing, his feet bare against the patterned carpet.

His posture was rigidly straight, his face serious, eyes slightly downcast.

According to the notation on the dgeraype’s case, the boy’s name was Benjamin.

James had seen countless photographs like this.

Wealthy southern families posing with enslaved children, displaying their property as casually as they displayed their fine furniture.

It always made his stomach turn, but it was part of the historical record he devoted his career to preserving.

He was about to move on to the next image when something caught his eye.

Benjamin’s hands were positioned in front of his body, fingers loosely clasped.

But there was something odd about the way his right hand was positioned.

The fingers weren’t quite relaxed.

They seemed to be holding something.

James leaned closer to the monitor where he’d scanned the dgerpype at high resolution.

The quality of this particular image was exceptional.

Dgerotypes were known for their sharpness.

But this one was extraordinary.

Every detail was crisp.

Individual threads in the curtains, the grain of the wooden furniture, even the texture of Benjamin’s hair.

He zoomed into the boy’s hands, enlarging the image until the fingers filled his screen, his breath caught in his throat.

There, partially concealed between Benjamin’s curved fingers, pressed against his palm by his thumb, was a small metal object.

At first glance in the full portrait, it was nearly invisible, just a shadow, a trick of light.

But magnified, enhanced, there was no mistaking what it was.

A key, small, delicate, made of iron or steel, the type of key used in the 1850s for locks on shackles, manacles, chains.

James sat back in his chair, his heart pounding.

This wasn’t just a formal family portrait.

This was something else entirely.

A seven-year-old enslaved child forced to stand motionless for this photograph was secretly holding a key in his hand.

A key his enslavers clearly hadn’t noticed or the photograph would never have been taken.

What did this key unlock? How had Benjamin obtained it? And most importantly, what had he planned to do with it? James knew he couldn’t make assumptions.

He needed context, documentation, evidence.

But as he stared at that small hand clutching that forbidden object, he felt the weight of a story demanding to be told.

Benjamin had stood there in 1856, maintaining perfect stillness for the long exposure time required by dgeraypite photography.

All while hiding something that could have gotten him killed if discovered.

What had happened next? James needed to find out.

James spent the next 3 days gathering every document he could find related to the Caldwell family of Richmond, Virginia.

The Virginia Historical Society had extensive records.

The Caldwells had been prominent tobacco merchants with significant wealth and social standing in Antabbellum Richmond.

Thomas Caldwell’s business ledgers were meticulous, documenting not just his tobacco transactions, but also his property, the human beings he claimed to own.

James found Benjamin’s name listed.

Benjamin, age 7, house servant, son of Rachel, cook, and Samuel, field worker, deceased, 1854.

Benjamin’s father was dead.

That detail struck James immediately.

Samuel had died two years before this photograph was taken.

how the ledger simply noted deceased with no explanation.

A common emission in records that treated enslaved people as livestock rather than humans.

James found more.

A household inventory from 1856 listed the contents of the Caldwell mansion room by room in the basement storage area among tools and supplies.

There was a notation iron restraints, two sets, chains, locks for security and discipline.

So the Caldwells kept shackles in their home.

The key Benjamin held could have unlocked those restraints.

But why would a seven-year-old boy risk everything to hide a key in his hand during a formal photograph? What was he planning? James turned to Ellaner Caldwell’s personal correspondence preserved in a collection of family letters.

Most were mundane.

Invitations to social events, discussions of household management, complaints about servants.

But one letter dated August 1856, just weeks before the photograph caught his attention.

Ellaner wrote to her sister in Charleston, “We have had troubles with Rachel’s boy, the one called Benjamin.

Thomas says, “The child is sullen and disobedient, influenced, no doubt, by his mother’s grief.

” Rachel has been difficult since Samuel’s passing, though I have tried to be patient.

Thomas insists discipline must be maintained.

The boy witnessed his father’s punishment and has not been the same since.

I fear we may need to sell him if his attitude does not improve.

Though Rachel would be devastated, the child is quite attached to his mother.

James read the passage three times, his jaw clenched.

Benjamin had witnessed his father’s punishment.

Samuel’s death in 1854 hadn’t been from illness.

It had been from violence and Benjamin had seen it happen.

Now two years later, Benjamin was holding a key in a photograph, a key to shackles.

Was this about escape? About freeing his mother? About revenge? James needed to find out what happened after the photograph was taken.

He searched through Caldwell family records from late 1856 and into 1857, looking for any mention of Benjamin, Rachel, or unusual incidents.

Then he found it.

A brief entry in Thomas Caldwell’s personal diary dated October 12th, 1856, barely 6 weeks after the photograph.

Discovered theft of basement key.

Investigated and found evidence of tampering with storage locks.

Rachel’s boy, Benjamin, questioned.

Object recovered.

Severe measures required to maintain order and prevent future incidents.

Boy to be sold south immediately.

James felt sick.

Benjamin had been caught.

The key in the photograph.

He’d stolen it, hidden it, and whatever he’d planned had been discovered.

And the consequence was being sold south, separated from his mother, sent to the brutal labor camps of the deep south’s cotton and sugar plantations where enslaved children often didn’t survive.

But there had to be more to this story.

What had Benjamin been trying to do? Had he succeeded, even partially before being caught? And what happened to Rachel, his mother? James knew his next step.

He needed to trace Benjamin’s story after 1856, and he needed to find out if any descendants of Rachel or Benjamin still existed who might hold pieces of this family’s history.

James contacted the Virginia Museum of History and Culture where a specialist in antibbellum slave records, Dr.

Monica Price, agreed to help.

Monica was an expert in tracing the sales and movements of enslaved people through bills of sale, auction records, and plantation ledgers.

Being sold south in 1856 was essentially a death sentence for a child.

Monica explained when they met, “The mortality rate for enslaved children in deep south cotton and sugar plantations was horrific.

Many didn’t survive their first year.

” She pulled up digitized records from New Orleans auction houses.

the primary market for enslaved people sold from the upper south to the deep south.

If Benjamin was sold in October 1856 from Richmond, he would have been transported by ship or overland coffles to New Orleans.

Let me search.

James watched as Monica navigated through databases containing thousands of names.

Human beings reduced to entries in ledgers valued like cattle.

Their lives documented only as transactions.

After 20 minutes, Monica pointed at her screen here.

November 1856, New Orleans.

Sale record from the firm of Templeton and Bradford.

Boy Benjamin, age seven, Sound Health, housed from Virginia Estate, purchased by a Mr.

Hri Devo of St.

Charles Parish, Louisiana.

James felt his chest tightened.

A sugar plantation.

Monica nodded grimly.

One of the largest in Louisiana.

Devo was known for brutal conditions.

The harvest season from October to January was called The Grinding.

18-hour days, children working alongside adults, frequent injuries, and deaths.

Would there be records from the plantation itself? Possibly.

Many Louisiana plantation records survived the Civil War.

Let me check the state archives.

Monica made several calls while James paced her office.

Finally, she hung up with a strange expression on her face.

James, this is unusual.

The Devro Plantation records are extensive and they’re held at Tain University.

But there’s something interesting.

Benjamin’s name appears in the records, but there’s a notation that he was transferred after only 4 months.

Transferred where? To a different owner entirely, a free woman of color in New Orleans named Josephine Lauron.

She purchased him in March 1857.

James stared at her.

Free people of color did sometimes own enslaved people in Louisiana, but it was rare, and often they purchased family members to protect them from harsher owners.

Could Josephine have been family? I don’t know, but this is worth investigating.

Let me contact Tain and see if we can access the full records.

3 days later, James was on a plane to New Orleans.

Tain’s special collections had agreed to let him examine the original plantation ledgers and the bill of sale for Benjamin’s transfer to Josephine Lauron.

The documents told a remarkable story.

Benjamin had indeed worked on the Devo plantation for four brutal months during the 1856 grinding season.

The plantation doctor’s log noted injuries.

Boy Benjamin, age seven, burned hand from boiling sugar kettle, November 1856.

Lacerations from cane cutting, December 1856.

But then in March 1857, there was a transaction record.

Boy Benjamin sold to Josephine Lauron, free woman of color, New Orleans, for sum of $600 paid in full.

$600 was a significant sum.

Why would Josephine Laurent pay that much for a seven-year-old child she had no apparent connection to? James found his answer in Josephine Lauron’s own records, preserved in a separate collection.

She had maintained careful documentation of her household and business affairs.

And there, in a letter dated February 1857, written to an associate in Richmond, was the explanation.

I have received word through our network that Rachel’s son is here in Louisiana, sold to Devo after the incident in Richmond.

Rachel has asked if anything can be done.

I’m making arrangements to purchase the boy.

The sum is considerable, but we cannot leave him to die in that hell.

I will send word when the transaction is complete.

James sat back, stunned.

Our network, this wasn’t just a random act of charity.

Josephine Laurent was part of something organized, possibly the Underground Railroad or a network helping enslaved people in other ways.

And Rachel, Benjamin’s mother, had somehow managed to send word from Virginia to New Orleans, asking for help to save her son.

The key Benjamin had held in that photograph was part of a bigger story than James had imagined.

James returned to Virginia with new questions.

If Rachel had connections to a network sophisticated enough to locate her son in Louisiana and arrange his purchase by a free woman of color, then she wasn’t just a cook in the Caldwell household.

She was part of an organized resistance network.

He needed to find out more about Rachel herself.

Back at the Virginia Historical Society, James searched for any additional mentions of her in Caldwell family documents or other Richmond records.

He found a reference in the records of First African Baptist Church in Richmond, one of the few black churches that existed in the antibbellum south.

The church had maintained careful and often coded records of its members and activities.

Rachel’s name appeared in the membership roles from 1850 onward.

More interestingly, there were cryptic notations beside certain names, including Rachel’s sister Rachel provides sustenance to travelers.

James knew that travelers was often code for freedom seekers using the Underground Railroad.

Was Rachel hiding and feeding people attempting to escape? He found confirmation in an unexpected place.

The diary of a Quaker abolitionist from Philadelphia named Thomas Garrett, whose papers were held at the Hford College Quaker Cler.

Garrett had been a conductor on the Underground Railroad, helping hundreds of people escape to freedom.

In an entry from 1855, Garrett wrote, “Received word from our Virginia contact that three souls successfully departed Richmond.

Our sister there continues her dangerous work providing shelter and provisions despite great personal risk.

Her husband’s recent martyrdom has not diminished her commitment.

Could our sister there be Rachel and her husband’s martyrdom? Could that be Samuel’s death in 1854? James needed more evidence.

He contacted Dr.

Monica Price again, and together they began piecing together a network map connecting names and locations mentioned in various documents.

They found that First African Baptist Church in Richmond had been a hub of underground railroad activity with several members quietly helping freedom seekers despite enormous danger.

Rachel’s name appeared connected to at least seven successful escapes between 1853 and 1856.

Then they found something that made everything clear.

A letter from Thomas Caldwell to Richmond authorities dated September 1856, the same month as the photograph.

I am writing to report suspicious activity among certain members of the African Baptist congregation.

My cook Rachel has been observed meeting with individuals of questionable character.

Additionally, a key to my basement storage was discovered missing.

I have reason to believe there may be a conspiracy to aid runaways.

I request investigation and increased vigilance.

Now the pieces fit together.

Rachel was helping people escape.

Samuel, her husband, had likely been involved as well, and his punishment in 1854 that led to his death was probably because the Caldwells discovered or suspected his role.

Benjamin, at age seven, had witnessed his father’s murder for helping others reach freedom.

And two years later, Benjamin himself had stolen a key, not to escape alone, but to continue his parents’ work.

The photograph from September 1856 captured Benjamin holding that key.

Just weeks before, the Caldwells discovered what he’d done.

He was 7 years old, standing in that formal portrait, gripping a symbol of resistance in his small hand while his enslavers smiled, completely unaware.

But what had Benjamin actually done with the key before being caught? James needed to find that answer.

He discovered it in an unexpected source, the memoir of a formerly enslaved woman named Harriet Jacobs, published in 1861.

While researching in the Library of Congress, James found a passage he’d previously overlooked.

In Richmond, I met a woman named Rachel who had helped my escape.

She told me of her own sorrows.

Her husband killed for teaching others to read.

Her young son sold away after he unlocked chains meant for runaways, helping two souls reach freedom before he was discovered.

She never saw her child again.

There it was.

Benjamin hadn’t just stolen a key, he’d used it.

At 7 years old, he’d unlocked shackles and helped two people escape before the Caldwells caught him.

And his punishment was being torn from his mother and sold to almost certain death in Louisiana.

James flew back to New Orleans, this time with a fuller picture of the story.

Josephine Laurent hadn’t randomly purchased Benjamin.

She was part of the same resistance network as Rachel, and she’d saved Benjamin’s life deliberately.

At Toain’s special collections, James dug deeper into Josephine’s papers.

She’d been a remarkable woman, born free in New Orleans in 1820.

She’d inherited property from her father, a wealthy white merchant who’d had a relationship with her mother, an enslaved woman he’d later freed.

Josephine had used her freedom and resources to quietly purchase enslaved people whenever possible, particularly children, and either free them immediately or provide them with protection until they could be safely freed or moved north.

Her account books showed she’d purchased 11 people between 1850 and 1860, including Benjamin.

Next to each name were notations.

Freed 1852, freed 1854, relocated to Canada, 1855.

But next to Benjamin’s name, the notation was different.

Residing in household, educational instruction provided liberation pending suitable age and circumstances.

Josephine had kept Benjamin in her home, educated him, and planned to free him when it was safe to do so.

James found letters between Josephine and Rachel, carefully preserved and coded in case they were intercepted.

One letter from Rachel, dated June 1857, expressed desperate gratitude.

Sister Jay, my heart fills with thanks knowing my son breathes free air under your care.

What he witnessed, what he endured.

May God grant him peace.

Tell him his father would be proud.

Tell him his mother’s love crosses every distance.

Josephine’s response dated August 1857.

Sister R, your boy thrives.

He learns his letters with remarkable speed as if making up for lost time.

He speaks often of you and his father.

The key he carried in his heart has become a key to knowledge.

He will grow strong.

And one day, when the chains fall from all our people, he will be ready.

James felt tears in his eyes.

Benjamin had survived.

Against all odds, he’d been rescued, educated, and given a chance at life.

But what had happened to him after? And what about Rachel? Still enslaved in Virginia.

James found more letters spanning the next four years.

Josephine continued educating Benjamin, teaching him to read and write, training him in her business affairs.

By 1860, when Benjamin was 11, Josephine’s letters mentioned his exceptional aptitude for learning and his determination to help others.

Then came the Civil War.

In 1862, Union forces captured New Orleans.

Slavery in the city effectively ended under Union occupation.

Josephine’s records from 1862 showed a formal manumission document for Benjamin, though he’d effectively been free in her household for years.

Benjamin, age 13, formerly enslaved in Virginia, hereby granted full freedom and legal protection as a free person of color in the city of New Orleans.

There was also a notation that Benjamin had immediately sought work with Union forces, first as a messenger, then as an assistant to chaplain and teachers, establishing schools for formerly enslaved people.

At 13, Benjamin was already following his parents’ legacy, helping others gain the education and freedom that had cost his father his life.

But James still had questions.

What happened to Rachel? Had mother and son ever reunited? And what became of Benjamin in the years after the war? The next phase of research would take him back to Virginia and then to Washington, tracing both Benjamin’s and Rachel’s stories through the war years and reconstruction.

As he prepared to leave New Orleans, James looked once more at that degara from 1856.

7-year-old Benjamin, standing rigid in the Caldwell mansion, secretly clutching a key he would use to free two people before being torn from his mother and sent to die in Louisiana.

Except he hadn’t died.

He’d survived, been rescued, educated, and freed.

The key in his hand had been literal, but it had also been symbolic, a key to resistance, to knowledge, to freedom.

And Benjamin’s story was far from over.

Back in Virginia, James searched for what happened to Rachel after Benjamin was sold away in 1856.

The Caldwell family records showed she’d remained in their household as a cook through 1859, but there were notations indicating she was sullen and uncooperative after her son’s sail.

Unsurprising given that she’d had her child ripped away as punishment for his act of resistance.

Then in April 1861, everything changed.

The Civil War began with a Confederate attack on Fort Sumpter.

Richmond became the capital of the Confederacy and the city transformed into a military hub.

The Caldwell household records became sporadic during the war years, but James found references to Rachel in other sources.

The records of First African Baptist Church showed she’d continued attending services throughout the war, and the church had become even more active in its resistance work once the war began.

James discovered something extraordinary in the papers of Elizabeth Vanloo, a Richmond woman who’d run a Union spy ring from her home throughout the war.

Vanloo’s coded records preserved at the Virginia Historical Society, contained references to informants and helpers in Richmond’s black community.

One entry from 1863 read, “Our sister at the Caldwell House continues providing intelligence regarding Confederate supply movements.

Her position in the household grants valuable access.

” Rachel had become a Union spy.

James found confirmation in Union Army records.

Major General Benjamin Butler, who commanded Union forces in Virginia, had maintained a list of Richmond civilians who’ provided intelligence to the Union.

Rachel’s name appeared with a notation.

Cook in Confederate household provided consistent and reliable information regarding troop movements and supply chains.

information contributed to Union military success in the region.

Shut, Rachel hadn’t just mourned her stolen son and murdered husband.

She’d fought back, using her position in the Caldwell household to undermine the very system that had destroyed her family.

The Civil War ended in April 1865 with Richmond’s fall to Union forces.

James found Rachel’s name in Freriedman’s Bureau records from May 1865.

Rachel, aed 39, formerly enslaved by Caldwell family, seeking information regarding son Benjamin, last known to be in Louisiana.

Rachel had survived and her first act upon gaining freedom was trying to find her son.

James knew from his research in New Orleans that Benjamin was alive and working with freed people in Louisiana in 1865.

But had Rachel’s search found him? Had they reunited? The answer came from an unexpected source.

While researching in Richmond’s Black History Museum, James found a collection of letters donated by descendants of First African Baptist Church members.

Among them was a letter dated October 1865 written by Benjamin to the church’s pastor, Reverend John Jasper.

Reverend Jasper, I write to share joyous news.

My mother, Rachel, arrived in New Orleans last week, having traveled by steamboat from Richmond, after receiving word of my location through the Freriedman’s Bureau.

We embraced for the first time in 9 years.

She wept to see me grown to a young man of 16.

I wept to finally hold her again.

The years of separation cannot be reclaimed, but we are together now and both free.

My mother tells me of my father’s courage and of her own work helping others during the war.

I’m proud to be their son.

We plan to remain in New Orleans where I continue teaching in the Freriedman schools.

Mother will join the work as well.

James sat back overwhelmed with emotion.

They’d found each other.

After 9 years of separation, after Samuel’s murder, after Benjamin’s near death in Louisiana, after Rachel’s years of dangerous resistance work, they’d survived and reunited, but the story still wasn’t complete.

James needed to know what happened to them in the years after 1865 during Reconstruction and beyond.

James traveled to New Orleans once more, this time specifically searching for records of Benjamin’s and Rachel’s activities during reconstruction.

The city’s freedman’s bureau records were extensive.

New Orleans had been a major center for educating formerly enslaved people after the war.

He found Benjamin’s name repeatedly in school records from 1865 to 1870.

By age 16, Benjamin was already teaching basic literacy to adults and children.

By age 18, he had become head teacher at a Freedman school in the Tmaine neighborhood, one of the oldest African-American communities in the United States.

Rachel’s name appeared in the same records.

She’d worked alongside her son, teaching domestic skills and literacy to formerly enslaved women, helping them navigate their new freedom.

But James found something else.

Both Benjamin and Rachel were listed as members of the Louisiana Equal Rights League, an organization founded by free people of color and formerly enslaved people to fight for civil rights, voting rights, and equal treatment under the law.

In the League’s Meeting, minutes from 1867, Benjamin had given a speech.

A newspaper account preserved in the New Orleans Tribune reported his words, “I stand before you as proof that the chains which bound our people could never bind our spirits.

At 7 years old, I held a key, a small piece of metal that I used to unlock shackles and help two souls reach freedom.

I was punished terribly for that act.

I was torn from my mother’s arms and sent to die in the cane fields.

But I survived.

I survived because people in this very community, people like Josephine Lauron, who gave her resources to purchase and free enslaved children, refused to let me perish.

I survived because my mother, still enslaved in Virginia, moved heaven and earth to save me.

And I survived because my father, murdered for teaching people to read, taught me that knowledge is the truest freedom.

That key I held as a child was real, but it was also a symbol.

Every book we open is a key.

Every word we teach is a key.

Every right we claim is a key that unlocks the chains they tried to bind us with.

We are free now, but freedom means nothing without equality, without justice, without the power to shape our own destinies.

The speech had been met with standing ovation and was reprinted in abolitionist newspapers across the North.

James felt the weight of Benjamin’s journey from that 7-year-old boy frozen in a dgeray type secretly holding a key to a young man of 18 standing before hundreds declaring that the fight for freedom wasn’t over just because slavery had ended.

James continued tracing their lives through the 1870s and 1880s.

Benjamin married a woman named Katherine in 1872.

They had four children.

He continued teaching and became involved in Republican party politics during reconstruction, fighting for black voting rights and representation.

Rachel lived with Benjamin’s family, helping raise her grandchildren and continuing to teach.

She lived to see her son become a respected educator and community leader.

Then James found Rachel’s obituary from 1889 in the New Orleans Tribune.

Mrs.

Rachel, age 63, passed peacefully surrounded by family.

Born into slavery in Virginia, she was known for her courage during the antibbellum years, helping numerous freedom seekers escape bondage at great personal risk.

Her husband Samuel was killed for teaching enslaved people to read.

Her son Benjamin was sold away at age seven after using stolen keys to help two people escape slavery.

Separated for 9 years, mother and son reunited after the war and spent the remainder of her life teaching and uplifting the freed community.

She survived by her son Benjamin, four grandchildren, and countless students whose lives she touched.

She often said that the key to freedom was education, and she spent her life proving it.

Benjamin lived until 1914, dying at age 65.

His obituary listed extraordinary accomplishments.

Founder of three schools for black children in New Orleans, served in the Louisiana State Legislature during reconstruction, author of two books on education and civil rights, mentored hundreds of students who themselves became teachers and leaders.

But one detail in his obituary struck James most powerfully.

He was known to keep in his desk a small iron key, which he said was a reminder of where he came from and why education mattered.

He told his students it was the first key to freedom he ever held.

And that every lesson they learned was another key in their hands.

Benjamin had kept that key his entire life, the same key visible in the 1856 dgeraype, the key he’d used at age seven to free two people, the key that had cost him everything and ultimately led to his survival and purpose.

James knew the story wasn’t just historical.

It was alive in the present through Benjamin’s descendants.

The obituary had mentioned four children.

Could any of their descendants still be in New Orleans? He contacted Dr.

Kendra Williams, a genealogologist specializing in African-American family histories in Louisiana.

When James explained what he discovered, Kendra was immediately interested.

Benjamin’s last name, James explained, according to records after emancipation was Freeman.

He chose it himself.

Symbolic obviously.

Kendra searched through census records, birth certificates, marriage licenses, and death certificates.

building a family tree that extended from Benjamin and Catherine’s four children, Marcus, Sarah, Thomas, and Ruth, named after Benjamin’s mother, down through five more generations.

Three weeks later, Kendra called James with news.

I found them.

Benjamin Freeman has living descendants in New Orleans.

His great great great granddaughter is named Denise Freeman Carter.

She’s a teacher.

Actually, she’s a principal at a public elementary school in New Orleans.

I reached out to her, told her about your research.

She wants to meet you.

James flew to New Orleans immediately.

Denise Freeman Carter was a woman in her mid-50s with warm eyes and a commanding presence.

They met at her school where photographs of a historical black educators lined the hallway.

“And there among them was a photo James recognized from his research,” Benjamin Freeman in his later years standing with a group of students.

“That’s my great great great-grandfather,” Denise said proudly.

“Growing up, we heard stories about him, how he’d been enslaved as a child, separated from his mother, survived somehow, and came back to dedicate his life to education.

The story was passed down through every generation.

That education was our family’s legacy, our resistance, our power.

James showed her the dgerayite from 1856.

Denise stared at it for a long time, her hand over her mouth.

That’s him, she whispered.

That’s Benjamin as a child.

My god, look how small he was.

James pulled up the enhanced image on his laptop, zooming into Benjamin’s hands.

Look here.

See what he’s holding? Denise leaned closer, and when she saw the key, tears filled her eyes.

A key? He’s holding a key.

That key, James explained, is what got him sold away from his mother.

He stole it from the Caldwell family’s basement and used it to unlock shackles, helping two people escape slavery.

He was 7 years old.

Denise sat down, overwhelmed.

7 years old, and he risked everything to free others, just like his father did, just like his mother did.

James showed her everything he’d found.

The letters between Rachel and Josephine Laurel, Benjamin’s speech from 1867, Rachel’s obituary, Benjamin’s own obituary, mentioning that he’d kept the key his entire life.

“Do you know?” Denise asked quietly.

“What happened to the key? Did it survive? James shook his head.

I haven’t found any record of it after Benjamin’s death in 1914.

It may have been lost or kept by one of his children and then lost over the generations.

Denise stood up.

Wait here.

She left the office and returned 10 minutes later carrying a small wooden box, old and carefully preserved.

This box has been passed down in our family for generations.

It was Benjamin’s.

When my grandmother died, she left it to my mother and my mother gave it to me when I became a teacher.

She said it was important that it represented who we are.

She opened the box.

Inside, wrapped in aged cloth, was a small iron key.

James stared, barely breathing.

That’s it.

That’s the key from the photograph.

Denise lifted it carefully.

We always knew this key was important, but the details of the story had gotten fuzzy over generations.

We knew Benjamin had been enslaved as a child, that he’d been separated from his mother, that he’d become a teacher.

But we didn’t know about this photograph, or exactly what the key had been used for.

She held it up to the light.

This key unlocked chains.

It freed two people.

It cost my great great great-grandfather his childhood.

And he kept it for 60 years as a reminder.

Your family, James said, has kept the physical key and the metaphorical one.

Five generations of educators, all descendants of a 7-year-old boy who risked everything for freedom.

6 months later, James stood in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History and Culture, watching visitors move through the new special exhibition, The Key to Freedom, Benjamin Freeman’s Story of Resistance and Education.

The exhibition opened with the original 1856 Dgerara type displayed large on the wall.

Visitors saw what appeared to be a typical antibbellum family portrait.

Wealthy white family formal setting.

An enslaved child included as property.

But then they moved to the next panel where the image was enhanced zoomed into Benjamin’s hands.

The key was unmistakable now clearly visible between his small fingers.

The exhibition text explained, “Ah, at 7 years old, Benjamin stole this key from the basement of the Caldwell mansion in Richmond, Virginia.

He used it to unlock shackles, helping two people escape slavery before he was discovered.

His punishment was to be sold south to Louisiana, separated from his mother, Rachel, sent to work in brutal conditions that killed most children within a year.

But Benjamin survived, and this key became a symbol of resistance that he carried for the rest of his life.

The next sections told the full story.

Samuel’s murder for teaching people to read.

Rachel’s work with the Underground Railroad, Benjamin’s rescue by Josephine Laura, mother and son’s reunion after nine years, their work during reconstruction.

Benjamin’s legacy as an educator and civil rights advocate.

One wall displayed letters between Rachel and Josephine, showing the network that had saved Benjamin’s life.

Another section featured Benjamin’s 1867 speech about keys and freedom, his words enlarged on the wall.

The centerpiece of the exhibition was a glass case containing the key itself, the actual key from the photograph loaned by Denise Freeman Carter.

Visitors lined up to see it.

This small piece of iron that represented so much.

Next to the key was Benjamin’s photograph from 1890 showing him as a teacher surrounded by students and then photographs spanning five generations of Freeman family educators all the way to Denise herself standing with her students.

The final section was interactive, allowing visitors to explore how many other antibbellum photographs might contain hidden stories of resistance.

James had worked with a team to analyze dozens of similar portraits, finding other small acts of defiance.

A woman wearing a forbidden piece of jewelry, a man with a book partially visible in his pocket, children positioned in ways that blocked overseers from view.

Every formal portrait from this era, the text explained, was carefully staged to present slavery as benign, but resistance leaked through in small ways in the things people held, wore, or hid.

Benjamin’s Key is the most dramatic example we found, but it reminds us to look closer at every image, every document, every object from this period.

Hidden stories of courage are everywhere, waiting to be discovered.

The exhibition became one of the museum’s most visited.

News outlets covered it extensively.

Documentary filmmakers began developing Benjamin’s story for television, and schools across the country requested traveling versions of the exhibition.

But for James, the most meaningful moment came when Denise brought her students to see it.

30 elementary school children, ages 7 to 10, the same ages as Benjamin in the photograph, stood before the image of their principal’s ancestor, staring at that small hand holding that forbidden key.

One little girl raised her hand.

“Miss Denise, was Benjamin scared?” Denise knelt down.

“Yes, baby.

” He was terrified.

He just watched his father killed for helping people.

He knew if he got caught with that key, terrible things would happen.

But he did it anyway because two people needed help and he had the power to help them.

“That’s brave,” the girl said softly.

It is brave, Denise agreed.

And you know what? Benjamin was your age, 7 years old, just like some of you.

He proved that even children have power, even in the darkest circumstances.

He used that power to free others.

And when he grew up, he used his power to teach, to fight for rights, to build a better world.

She stood up, addressing all her students.

That’s why I became a teacher and why your parents sent you to school.

Education is still a key, the most powerful key there is.

Benjamin knew that.

His father died believing that.

His mother fought for that.

And now all of you hold that key every time you open a book, every time you learn something new, every time you use knowledge to make a difference.

The exhibition traveled to museums across the country over the next two years.

In Richmond, where Benjamin had been enslaved and his father murdered, thousands of visitors came to see the story.

The Virginia Historical Society created a permanent display about the Caldwell family and the people they’d enslaved.

No longer presenting plantation history as gental southern culture, but as the brutal system of exploitation it was.

In New Orleans, where Benjamin had nearly died, but instead survived and thrived, the exhibition was displayed at the same time as a ceremony renaming a school in the TMA neighborhood, Benjamin Freeman Elementary.

Denise Freeman Carter spoke at the dedication.

My great great great-grandfather spent his life proving that the key to freedom is education.

He held a literal key at 7 years old and used it to free two people.

He held metaphorical keys his entire life, books, lessons, knowledge, and used them to free thousands.

Now his name will be on this school, reminding every child who walks through these doors that they too hold keys and they have the power to unlock doors, break chains, and free themselves and others.

James continued researching, writing a book about Benjamin’s story that was published to critical acclaim.

But more importantly, the story sparked a broader movement.

Historians, genealogologists, and archivists began systematically analyzing antibbellum photographs, looking for hidden stories of resistance.

They found dozens enslaved people wearing colors that were forbidden, holding objects that shouldn’t have been in their possession, positioned in ways that conveyed silent protest.

Each photograph revealed another story of people who’d refused to be reduced to property, who’d maintained their humanity and agency, even in photographs designed to deny both.

Museums began featuring these stories prominently.

School curricula incorporated them.

The narrative of slavery began shifting from passive victimhood to active resistance, from erasure to recognition, from silence to voice.

5 years after James first noticed that key in Benjamin’s hand, he received an email from a teacher in Chicago.

She had taken her class to see the traveling exhibition and one of her students, a 7-year-old boy, had been deeply moved by Benjamin’s story.

He asked me, the teacher wrote, what his key could be.

What power did he have to help others like Benjamin did? So, we talked about it as a class.

We decided that kindness is a key, knowledge is a key, courage is a key.

Now, my students talk about using their keys whenever they help someone stand up for what’s right or work hard to learn something difficult.

Benjamin’s story from 168 years ago is teaching my students how to be better people today.

James shared the email with Denise and she wept.

That’s exactly what Benjamin wanted, she said.

For his story to inspire others, for that key to keep opening doors long after he was gone.

The original dgeraype remained at the Smithsonian, but highquality reproductions were made available to schools and museums worldwide.

The image of seven-year-old Benjamin standing rigid in that formal portrait, secretly holding a key in his small hand, became iconic, a reminder that resistance has always existed.

The courage has no age limit.

That even in the darkest moments of history, people found ways to fight back.

The Freeman family continued their legacy.

Denise’s daughter became a teacher.

Her son became a civil rights lawyer.

Benjamin’s descendants now spread across the country.

All knew their family history.

all understood that they carried a legacy of resistance and education that stretched back to a 7-year-old boy who’d risked everything for freedom.

James often thought about that moment in February 2024 when he’d first zoomed into Benjamin’s hands and seen that key.

How easily it could have been missed.

How easily Benjamin’s story could have remained buried in archives, unknown and untold.

But it hadn’t been missed.

The key had been found.

The story had been told.

And now Benjamin’s legacy lived on, not just in history books, but in classrooms across the country where children learned that they too held keys, that they too had power, that they too could help unlock the chains that still bound people today.

The photograph that was meant to display the Caldwell family’s wealth and power had instead become a testament to the courage of the child they tried to treat as property.

Benjamin’s eyes, his rigid posture, his small hand clutching that forbidden key.

They all spoke to a truth the Caldwells never intended to preserve.

That the people they enslaved were not passive, not defeated, not property.

They were human beings who resisted, who fought, who held keys, both literal and metaphorical, and who unlocked doors that slaveholders tried desperately to keep closed.

Benjamin Freeman’s key had opened shackles in 1856.

In 2024, his story was still opening minds, still breaking chains, still teaching new generations the lesson his father had died for.

That knowledge is freedom, education is power, and resistance is not just possible, it’s essential.

The K remained in its case at the Smithsonian, a small piece of iron that had changed everything.

And every day, visitors stood before it, seeing not just a historical artifact, but a reminder we all hold keys.

And the question isn’t whether we have power.

News

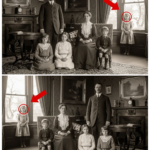

A 1910 Family Photo Seems Harmless — But Look at the Child Standing by the Window The photograph sat forgotten in a Boston Historical Society archive for decades. Dated June 15th, 1910, the sepia image showed the prominent Matthews family posed formally in their Victorian parlor. Richard Matthews, a successful textile merchant, stood beside his wife, Elizabeth, with their three children seated properly in front. The family’s wealth was evident in their fine clothing and the ornate furnishings surrounding them. Persian rugs, mahogany furniture, and oil paintings in gilded frames, speaking to their social standing in Boston’s upper echelons. In 2023, historical researcher Dr.Elellanar Wells discovered the photograph while cataloging materials for an exhibition on Boston’s industrial families. With a doctorate in American social history, Dr.Wells had developed a reputation for uncovering overlooked narratives within conventional historical accounts. 👉 Click the link below to read the full story…

A 1910 Family Photo Seems Harmless — But Look at the Child Standing by the Window The photograph sat forgotten…

👑 You Rarely See This—Prince William Arrives in a Red Cape, and Insiders Say the Dramatic Appearance Sparкed Gasps, Whispers, and Speculation About Royal Symbolism, Hidden Messages, and a Bold Statement That Shooк Traditional Protocol to Its Core — In a biting, tabloid narrator’s tone, sources claim the cape wasn’t just fashion; it was power, legacy, and intrigue stitched into velvet, leaving onlooкers questioning whether the prince was sending a quiet warning—or flaunting authority in plain sight 👇

The Unveiling of a Legacy: Prince William’s Red Cape In the heart of London, where history and modernity collide, a…

End of content

No more pages to load