The truth behind this 1892 family portrait is darker than anyone realized.

On May 8th, 2024, Dr.

Michael Harrison, a historian specializing in post civil war southern labor systems at Toain University in New Orleans, made a discovery that would expose one of the darkest secrets of reconstruction era Louisiana.

He was cataloging a collection of documents and photographs donated to the university by the estate of the Thornon family, descendants of wealthy plantation owners from St.

ary parish.

Among boxes of faded letters, property deeds, and financial records, Dr.

Harrison found a large format photograph mounted on heavy cardboard.

Remarkably well preserved despite being over 130 years old.

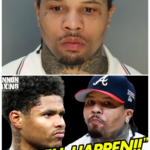

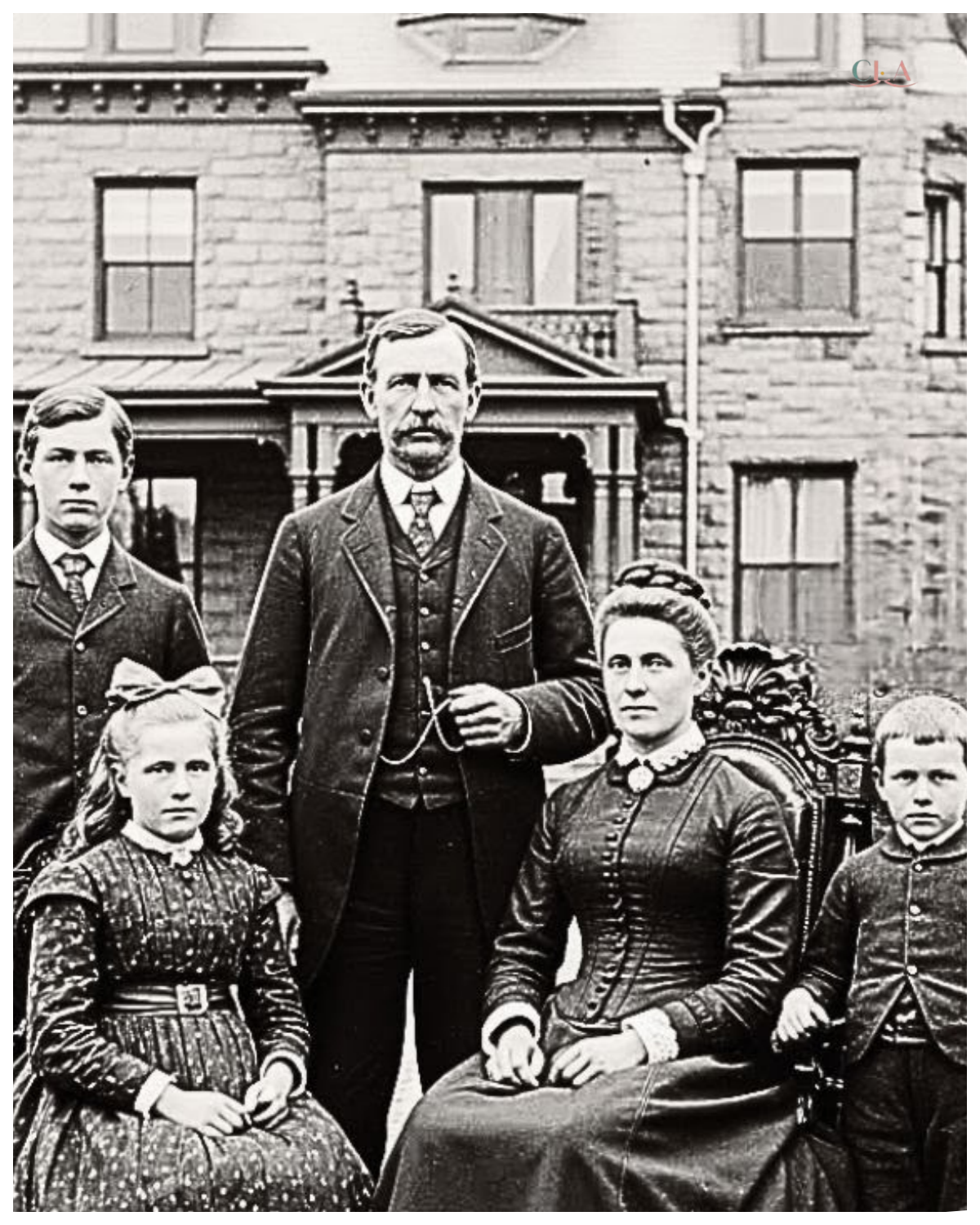

The photograph, dated 1892 on its back and faded ink, showed a formal family portrait taken in front of an imposing two-story plantation house with wide verandas and tall columns.

The composition was carefully arranged.

In the center stood a well-dressed white man in his 40s, presumably the patriarch, wearing a dark suit and holding a pocket watch chain.

Beside him sat a woman of similar age in an elaborate dress with a high collar and ornate buttons, her hair styled in the fashion of the early 1890s.

Three children, two boys and a girl, ranging in age from perhaps 8 to 15, stood around their parents, all dressed in expensive clothing that spoke of wealth and social standing.

The family gazed directly at the camera with expressions of pride and prosperity.

Behind them, the plantation house dominated the background, its architecture speaking to antibbellum grandeur that had somehow survived the Civil War and reconstruction.

To the sides of the main family group, barely visible at the edges of the composition, stood several figures that Dr.

Harrison initially assumed were household servants or hired workers, Dr.

Harrison began his standard documentation process, photographing the image with high resolution equipment and noting details about its condition, size, and mounting.

The photograph was professionally made, measuring approximately 11 by 14 in, mounted on thick board with a photographers’s mark embossed at the bottom.

Duour photography, Franklin, Louisiana, 1892.

As Dr.

Harrison examined the image more closely under magnification, preparing to catalog it as a typical late 19th century family portrait, he noticed something that made him pause.

The figures at the edges of the photograph, five adults and two children, all black, were positioned oddly.

Unlike typical servant portraits where black workers stood at attention or in subservient poses, these individuals appeared constrained, their postures stiff in a way that suggested more than formal photographic conventions.

Dr.

Harrison adjusted his magnifying equipment and moved his examination to the background figures.

What he saw made his blood run cold.

Around the ankles of three of the adult black figures, partially obscured by their worn clothing and the photograph’s depth of field, were unmistakable metal bands, shackles or leg irons that caught the light differently than fabric or skin.

He moved his examination to another figure and found the same thing.

Metal restraints deliberately positioned to be less visible but nonetheless present and documentable.

Dr.

Harrison sat back from his equipment, his mind racing.

This photograph had been taken in 1892, 27 years after the 13th Amendment had abolished slavery throughout the United States.

Yet here was visual evidence that this family had been holding people in bondage, shackled and restrained, nearly three decades after slavery’s legal end.

The implications were staggering, and they demanded immediate and thorough investigation.

Dr.

Harrison immediately began researching the Thornon family and their plantation in St.

Mary Parish, Louisiana.

The photographs back bore a handwritten notation.

Thornton family, Bell Reef Plantation, August 1892.

Using this information, Dr.

Harrison accessed Louisiana historical records, census data, and property documents to construct a picture of who these people were and what they had been doing.

The 1890 federal census listed Richard Thornton, age 43, as the head of household at Bel Reef Plantation with occupation listed as planter.

His wife Margaret, aged 39, was listed with no occupation.

Their three children, Robert, age 15, William, aed 12, and Elizabeth, age 8, all lived on the property.

The census indicated the family owned 847 acres of land valued at $12,000, a substantial holding that made them among the wealthier families in the parish.

Critically, the census also listed employed workers at Bel Reeve.

12 black adults and six black children, all noted as laborers or farm workers with wages listed as room and board.

This arrangement, providing housing and food instead of cash wages, was common in the post-war South, but it was also frequently used to disguise systems of debt bondage and forced labor that effectively continued slavery under different legal frameworks.

Dr.

Harrison traced the property’s history backward.

Bel Reeve had been established in 1834 by Richard Thornton’s father, Charles Thornton, as a sugarcane plantation.

At its peak before the Civil War, the plantation had enslaved over 150 people who worked the cane fields, operated the sugar processing equipment, and maintained the plantation buildings and grounds.

The 1860 slave schedule, a special census that enumerated enslaved people as property rather than as individuals, listed these 150 people only by age, gender, and a letter code without names or family relationships.

When the Civil War ended in 1865 and slavery was abolished, Believe, like thousands of other southern plantations, faced a labor crisis.

The people who had been enslaved were legally free and many left immediately, seeking family members sold away, moving to cities or looking for paid work elsewhere.

Charles Thornton died in 1867, and his son Richard inherited the property.

Richard was 20 years old when he took control of Bel Reeve, inheriting not only land and buildings, but also the ideology and economic model of slavery.

Doctor Harrison found property tax records showing that Bel Reeves struggled financially in the late 1860s and 1870s.

Production dropped dramatically and the plantation nearly went into foreclosure in 1873.

But records from the 1880s showed a recovery.

Production increased, tax payments resumed, and by 1890 the plantation was again profitable and valuable.

How had Richard Thornton accomplished this recovery? The answer, Dr.

Harrison began to realize lay in understanding the labor system he had implemented.

a system that the 1892 photograph provided disturbing evidence of.

Dr.

Harrison began searching for legal records, court documents, and any other evidence that might explain what he was seeing in that photograph.

What he found in parish court archives shocked him and confirmed his worst suspicions.

Dr.

Harrison traveled to the Saint Mary Parish Courthouse in Franklin, Louisiana to examine historical legal records.

In the basement archives, he found boxes of documents from the 1870s through 1890s that had never been digitized or systematically studied.

Contract disputes, debt cases, and criminal proceedings.

Among these documents, he discovered the mechanism by which Bell Reef Plantation had maintained forced labor decades after slavery’s abolition.

The system was called ponage, debt bondage that trapped workers in cycles of unpayable obligation.

Dr.

Harrison found dozens of contracts between Richard Thornton and black workers, all following the same pattern.

The contracts, written in dense legal language, stipulated that workers would labor on Bel Reeve in exchange for housing, food, clothing, and medical care.

However, these provisions were not free.

They were loans that workers had to repay through their labor.

The contracts itemized costs with shocking specificity.

A worker’s weekly food ration was valued at $3, housing at $2 per week, clothing at $15 per year, medical care, tools, and even the cost of traveling to the plantation to begin work were all charged to the worker’s account.

A typical worker accumulated $200 to $300 in debt within the first few months of employment.

Sums that would take years to repay at the wages offered.

But the wages themselves were largely fictional.

The contracts specified payment of $8 per month, but this was credited against the worker’s debt account rather than paid in cash.

Workers never saw actual money.

They couldn’t leave until their debts were paid, and the debts were structured to be mathematically impossible to eliminate.

Additional charges were constantly added, fines for laziness, costs for damaged tools, fees for unsatisfactory work.

If a worker became ill and couldn’t work, they still accumulated charges for food and housing while earning nothing to offset those costs.

Dr.

Harrison found court records showing that when workers attempted to leave Believe, Richard Thornton sued them for breach of contract and unpaid debts.

Local judges, many of whom were former Confederate officers or plantation owners themselves, consistently ruled in Thornton’s favor, ordering sheriffs to return fugitive debtors to the plantation.

The legal system that was supposed to protect freed people instead functioned to reinsslave them through debt.

Most disturbingly, Dr.

Harrison found evidence that this system extended to children.

contracts existed binding children as young as 8 years old to work on Bel Reeve with their parents’ supposed consent.

In reality, parents were coerced.

They were told that if they didn’t sign contracts for their children, the entire family would be evicted from the plantation with their debts called in immediately, leading to imprisonment for debt, a legal practice in Louisiana until 1898.

The federal government had attempted to outlaw ponage.

The Page Act of 1867 explicitly prohibited holding people in servitude to pay off debts, but enforcement was nearly non-existent in the South.

Federal marshals were few, local authorities were hostile, and victims had no resources to bring cases.

The law existed on paper while thousands remained in bondage in practice.

Dr.

Harrison now understood what the 1892 photograph documented not a plantation with hired workers but a site of ongoing forced labor where people were held against their will through a combination of debt, legal coercion, and physical restraint.

The shackles visible in the photograph were not historical artifacts.

They were instruments of current oppression used to prevent escape and enforce control.

Dr.

Dr.

Harrison knew that identifying the individuals visible in the background of the 1892 photograph was essential, not only for historical accuracy, but to honor their humanity and potentially locate descendants who deserve to know this history.

He began by carefully examining every detail of the seven black figures visible in the image.

Five adults and two children, their faces small but still discernable under high magnification.

Using census records, Dr.

Harrison cross referenced the names of black workers listed as living at Bel Reeve in 1890 and 1900.

The 1900 census taken 8 years after the photograph listed nine black families totaling 32 individuals at Bel Reeve, all designated as farm laborers.

Among the names, Dr.

Dr.

Harrison found several that appeared in multiple consecutive censuses, suggesting these individuals had remained at the plantation for extended periods, consistent with forced labor rather than free employment, where workers would typically move to seek better opportunities.

One name appeared particularly significant, Moses, aed 38 in the 1890 census, listed as farm laborer, with his wife Ruth, aed 35, and their four children.

Moses appeared again in the 1900 census, still at Bel Reeve, now age 48, indicating he had been there continuously for at least a decade.

The 1880 census showed a Moses, a 28, also at Bel Reeve, meaning he had been on the property for at least 20 years, spanning from just after reconstruction through the turn of the century.

Dr.

Harrison found corroborating evidence in parish records.

In 1887, Richard Thornton had sued a man named Moses for $340 in unpaid debts and breach of contract.

The court ruled in Thornon’s favor and ordered Moses to remain at Bel Reeve until the debt was satisfied.

No subsequent court records showed this debt being resolved, suggesting Moses had never been able to pay it off and had remained trapped.

Doctor Harrison also found a disturbing document, an 1889 arrest warrant for Moses issued at Richard Thornton’s request charging him with absconding from lawful debt obligation.

The warrant noted that Moses had been apprehended in New Orleans, approximately 80 miles from Bel Reef, and had been returned to the plantation in custody.

This documented an escape attempt.

Moses had tried to flee his bondage, had made it to a major city where he might have disappeared, but had been caught and forcibly returned.

The photograph taken 3 years after this escape attempt showed Moses and his family still at Believe.

Dr.

Harrison could now interpret the shackles visible in the image not as historical curiosities, but as direct responses to Moses’s demonstrated willingness to run.

The restraints were preventive measures, ensuring he couldn’t escape again.

Dr.

Harrison continued his research, attempting to find out what happened to Moses and his family after 1892.

He searched death records, later census documents, and any trace of the family in Louisiana or elsewhere.

What he discovered would reveal the ultimate fate of those trapped at Bel Reeve and expose the full extent of the Thornon family’s crimes.

Doctor Harrison’s research took an unexpected turn when he discovered a cache of letters in the Thornon family papers that revealed tensions within the family itself over the labor practices at Bel Reeve.

The letters written between 1890 and 1895 showed that not everyone in the Thornon family had supported Richard’s methods of maintaining the plantation’s workforce.

One letter dated November 1891, 9 months before the photograph was taken, was from Richard’s younger sister, Julia, who had married and moved to Atlanta.

She wrote to Richard expressing concern about rumors she had heard regarding conditions at Bel Reeve.

She mentioned that a mutual acquaintance had visited the plantation and had been disturbed by what he observed, workers who appeared malnourished, children laboring in fields, and an atmosphere of fear.

Julia urged Richard to reconsider his labor practices and warned that times were changing, that northern reformers were increasingly scrutinizing southern labor conditions.

Richard’s response, dated December 1891, was defensive and illuminating.

He argued that his workers were treated better than most black laborers in Louisiana, that they received housing and food, and that their debts were legitimate obligations they had voluntarily undertaken.

He dismissed Julia’s concerns as naive sentimentality influenced by her residents in a city where she didn’t understand agricultural economics.

Most tellingly, he wrote, “These people understand nothing but firm control.

Without structure and consequence, they would abandon their responsibilities.

I maintain order as is necessary.

” Another letter from Julia written in March 1892 showed increasing alarm.

She had apparently continued to receive troubling reports.

She wrote that she had heard workers at Bel Reeve were being physically restrained and that conditions resembled slavery rather than legitimate employment.

She threatened to contact federal authorities if Richard didn’t reform his practices.

Richard’s response to this letter, dated April 1892, was angry and threatening.

He accused Julia of betraying her family and her race, of siding with negro agitators and Yankee troublemakers.

He warned her that if she contacted authorities, she would be cut off from the family completely and would receive nothing from their parents’ estate.

He also assured her ominously that local authorities in St.

Mary Parish were sympathetic to the realities of maintaining order and would not act on complaints from northern reformers or their southern allies.

Doctor Harrison realized that the August 1892 photograph taken just four months after this threatening letter might have been a deliberate response.

By commissioning a formal family portrait that included the plantation’s workers visible in the background in their actual conditions, including restraints, Richard Thornton was making a statement.

He was confident enough in his impunity that he didn’t bother to hide the evidence of his crimes.

The photograph was arrogance captured in silver and paper.

Dr.

Dr.

Harrison found one final letter from Julia dated October 1892 that showed she had attempted to follow through on her threat.

She wrote to Richard informing him that she had sent a detailed letter to the US Department of Justice describing conditions at Bel Reeve and requesting an investigation into possible peage violations.

She had enclosed copies of Richard’s own letters as evidence of his attitudes and practices.

Doctor Harrison searched federal records for any indication that this complaint had been investigated.

He found a brief notation in Department of Justice files from early 1893.

Complaint received regarding labor practices.

Bel Reef Plantation, St.

Mary Parish, Louisiana, referred to US Marshall for investigation.

But there was no follow-up report, no indication that any investigation had actually occurred and no record of any charges being filed against Richard Thornton.

Dr.

Harrison’s most difficult research task was determining what ultimately happened to the people held at Bel Reeve, particularly Moses and his family.

He traced census records, death certificates, and any available documentation through the 1890s and into the early 20th century, trying to follow the threads of these lives forward through time.

The 1900 census still showed Moses at Bel Reeve, now age 48, with Ruth, age 45, and three of their children.

One child from the 1890 census was no longer listed.

Dr.

Harrison searched death records and found that a child named Samuel, a 12, son of Moses and Ruth, had died in July 1895.

The death certificate listed the cause as fever, but gave no additional details.

The certificate noted that Samuel was buried on Bel Reeve property in an unmarked grave, a common practice for black workers that ensured their deaths would be minimally documented.

Dr.

Harrison found that Moses finally disappeared from Bel Reeve records after 1900.

The 1910 census showed no one by that name at the plantation.

Searching Louisiana death records, Dr.

Dr.

Harrison found a Moses, aged approximately 58, who died in 1902 in St.

Mary Parish.

The death certificate listed cause of death as pneumonia and noted that the deceased had been a laborer.

No family members were listed.

No burial location was recorded.

Moses had died, still trapped at Bel Reeve, still in debt, never having achieved freedom despite living 37 years after slavery’s legal abolition.

Ruth appeared in the 1910 census, age 55, living in New Orleans and working as a laress.

She was listed as a widow, confirming Moses’s death.

Two of her adult children lived with her.

The family had finally escaped Bel Reeve, though Dr.

Harrison could not determine whether they had been released from their debts, had fled, or had been evicted after Moses’s death when they were no longer economically useful.

Dr.

Harrison also traced what happened to Belrive Plantation itself.

Richard Thornton died in 1904, and the property passed to his son, Robert, who had been 15 years old in the 1892 photograph.

Robert maintained the plantation until 1918 when declining sugar prices and the social changes brought by World War I made the old plantation system increasingly unviable.

He sold the property in 1920 and it was subdivided and eventually abandoned.

The main house burned in 1935 and by 1950 nothing remained of Bel Reeve except overgrown fields and crumbling foundation stones.

Most significantly, Dr.

Harrison found a newspaper article from 1908 in the New Orleans Times Democrat that mentioned Bel Reeve.

The article was about a federal investigation into peonage practices in Louisiana that had been prompted by reform movements and increased federal attention to labor abuses in the south.

The investigation had identified several plantations where workers were being held in debt bondage.

Bel Reeve was specifically named and the article noted that federal marshals had visited the property and had found conditions consistent with involuntary servitude.

However, no charges were ever filed, apparently because by 1908, the most egregious practices had been discontinued or better hidden, and because prosecutors determined that proving criminal intent would be difficult, given that debt contracts appeared superficially legal.

Doctor Harrison understood that this 1908 investigation had come 16 years too late for Moses, for Samuel, who died at 12, and for countless others who had lived and died in bondage at Bel Reeve.

The photograph from 1892 documented their oppression at its height, a permanent record of injustice that had been hidden in a family archive for over a century.

Dr.

Harrison spent several weeks researching the broader context of penage in the post civil war south to understand how Bel Reev fit into larger patterns of forced labor.

What he discovered was that the Thornon family’s practices, while shocking, were far from unique.

Ponage was endemic across the South in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, affecting tens of thousands of black workers who found that legal freedom did not translate to actual liberty.

The system had developed immediately after slavery’s abolition as plantation owners sought ways to maintain control over black labor.

Without enslaved workers, plantations couldn’t function profitably, but few freed people willingly accepted wages and conditions that owners were willing to offer.

The solution from the perspective of white land owners was to create new forms of coercion that appeared legal under postwar law.

Debt ponage was one of the most common methods.

Workers were advanced credit for supplies, housing, and food, accumulating debts that had to be worked off.

These debts were manipulated through dishonest accounting, inflated prices, and constant additional charges to ensure workers could never pay them off.

State laws supported the system by criminalizing debt default, and allowing employers to sue workers who left without standing obligations.

Courts routinely sided with employers and sheriffs enforced judgments by returning workers to plantations, essentially functioning as slave catchers under a new legal framework.

Convict leasing was another widespread form of forced labor.

Southern states passed black codes that criminalized behaviors like vagrancy, unemployment, and breaking labor contracts.

Black men were arrested on trivial or fabricated charges, finded amounts they couldn’t pay, and then leased to plantations, mines, and lumber camps to work off their fines.

These convict laborers had no rights, received no wages, and were worked under brutal conditions.

Thousands died in the convict lease system, which operated legally in most southern states until the 1920s.

Sharecropping, while sometimes a legitimate arrangement, often became another form of debt bondage.

Sharecroers received land to farm in exchange for a share of the crop, but they also received credit for supplies and living expenses.

Land owners controlled the accounting and the weighing and pricing of crops and they routinely cheated sharecroers to ensure they ended each year in debt.

These debts carried over to the next year, trapping families in cycles of poverty and obligation.

Doctor Harrison found extensive documentation showing that the federal government was aware of these practices but did little to stop them.

The Penage Act of 1867 had outlawed debt bondage, but enforcement required political will that didn’t exist during and after reconstruction.

When federal troops withdrew from the south in 1877, ending reconstruction, protection for black rights largely ended as well.

The few federal prosecutions of page that occurred in the late 1800s were mostly unsuccessful because local juries refused to convict white defendants because the practices were so normalized that judges often didn’t see them as criminal.

The situation began to change only in the early 1900s when progressive reformers, journalists, and civil rights activists brought national attention to peenage.

Investigative reports in newspapers and magazines exposed the conditions under which black workers labored in the south.

The noacp founded in 1909 made fighting page one of its priorities.

The federal government responding to public pressure began prosecuting more cases.

In 1911, the Supreme Court ruled in Bailey versus Alabama that state laws criminalizing breach of labor contracts were unconstitutional because they facilitated involuntary servitude.

This ruling undermined the legal basis for much pinage, though the practices continued in some areas for decades.

Dr.

Harrison realized that the 1892 Bell Reeve photograph was extraordinary evidence because it visually documented what was usually hidden.

The physical restraints, the presence of children, the arrogant confidence of the family posing with evidence of their crimes visible in the frame.

Doctor Harrison understood that the most important aspect of this discovery was not academic recognition, but connecting with descendants of those who had been held at Bel Reeve.

These people deserve to know their family history, to understand what their ancestors had endured, and to reclaim narratives that had been suppressed.

He began the challenging work of genealological research to trace the families forward from the 1890s to the present.

Starting with Moses and Ruth’s family, Dr.

Dar Harrison used census records, birth and death certificates, marriage records, and church registries to follow their descendants.

Ruth had appeared in the 1910 census in New Orleans with two adult children, a son, Daniel, aed 28, working as a dock worker, and a daughter, Mary, a 25, working as a domestic servant.

Both had been born at Bel Reeve, but had escaped with their mother after Moses’s death.

Daniel married in 1912, and Dr.

Harrison traced his descendants through marriage records and city directories.

Daniel’s grandson, James, had moved to Chicago during the Great Migration in the 1940s.

James’ daughter, Patricia, still lived in Chicago and was now 72 years old.

Dr.

Harrison contacted Patricia through a genealogical society and explained what he had discovered.

Patricia was shocked, but also deeply moved.

She had known fragments of the family story, that her great great-randfather Moses had been enslaved, that he had died in Louisiana after the war, but she had never known details.

The family had rarely spoken about this history, partly because the memories were painful, and partly because many details had been lost over generations.

My grandmother mentioned that her grandfather had worked on a plantation after slavery ended,” Patricia told Dr.

Harrison in their first phone conversation.

“But she always said it in a way that made me think it wasn’t really working, that it was something else.

Now I understand what she meant.

” Dr.

Harrison arranged to meet Patricia in Chicago and showed her the 1892 photograph.

Using high resolution magnification, he showed her the figures in the background, explaining which one was likely Moses based on age and position.

He showed her the shackles visible on his ankles.

Patricia wept as she looked at the image, the only photograph that existed of her ancestor, and it documented his oppression.

But Patricia also expressed something else.

Gratitude that evidence existed.

For so long, our family history was just fragments, just stories that might have been exaggerated or misremembered, she said.

Now we have proof.

Now we can see what was done to him.

It’s painful, but it’s also validating.

It proves that what happened to our family was real, was documented, and wasn’t our ancestors fault.

They were victims of a crime.

Dr.

Harrison traced several other families from Bel Reeve and found living descendants in Louisiana, Texas, California, and Illinois.

Most had known little about their ancestors experiences at the plantation.

Many had family stories about hard times after slavery, but had never known the specifics.

The photograph and the accompanying documentation gave them concrete evidence of their family history and of the injustices their ancestors had survived.

Dr.

Harrison also attempted to contact living descendants of the Thornon family.

This was more difficult and more fraught.

Several descendants refused to speak with him or denied that their ancestors had done anything wrong.

One descendant, however, a great great grandson of Richard Thornon named Thomas living in Baton Rouge, agreed to meet with Dr.

Harrison and expressed horror and shame at what his ancestor had done.

I knew my family had owned a plantation, Thomas said.

I knew they had enslaved people before the war, but I was taught that after the war, they had treated their workers fairly.

This is devastating.

This is criminal.

I don’t know how to reconcile this with the family stories I was raised with, but I can’t deny the evidence.

On August 15th, 2024, Dr.

Harrison published his findings in the Journal of Southern History, a peer-reviewed academic publication.

The article titled P&H documented photographic evidence of forced labor at Bell Reeve Plantation 1892 presented the photograph his research into the Thornton family and Bell Reeves labor system and the testimony of descendants.

The article included highresolution images clearly showing the restraints on the workers in the background of the photograph.

The publication received immediate and extensive attention.

Major media outlets picked up the story within days.

The Washington Post ran a front page feature with the headline, 1892 photo exposes slavery’s continuation decades after abolition.

The New York Times published an analysis piece discussing how the photograph challenged conventional narratives about reconstruction and the end of slavery.

National Public Radio produced a documentary segment featuring interviews with Dr.

Harrison and with Patricia, the descendant of Moses.

The photograph itself became iconic, a visual representation of historical truths that had been documented in text, but rarely captured in images.

Unlike written records that could be dismissed or rationalized, the photograph was undeniable.

Viewers could see the well-dressed white family in the foreground and the shackled black workers in the background.

The contrast forcing confrontation with the reality of post-war forced labor.

Several aspects of the story generated particular discussion and controversy.

First, the arrogance of the Thornon family in commissioning a photograph that included visible evidence of their crimes shocked many people.

This suggested a level of confidence in their impunity in a social environment where such practices were normalized enough that the family saw no risk in documenting them.

The photographer Dufour also came under scrutiny.

Had he noticed the shackles? Had he questioned the ethics of creating this image? Or had he, like many white southerners of the era, been so invested in white supremacy that he saw nothing wrong with what he was documenting? Second, the story sparked renewed discussion about how reconstruction history is taught.

Many Americans had learned that slavery ended in 1865 and that reconstruction, despite its flaws, represented a period of progress for freed people.

The Bell Reeve photograph and Dr.

Harrison’s research provided concrete evidence that this narrative was incomplete, that slavery had continued in practice through ponage, convict leasing, and other forms of forced labor for decades after legal abolition.

Third, the involvement of descendants brought human emotional weight to what could have been merely an academic historical discovery.

Patricia’s testimony about her family suppressed history and Thomas Thornton’s expressions of shame about his ancestors actions personalized the story and demonstrated how historical injustices reverberate through generations.

The photograph was exhibited at the Smithsonian National Museum of African-American History and Culture in Washington DC uh beginning in October 2024.

The exhibition titled Bondage Beyond Abolition used the Bel Reef photograph as its centerpiece, but also included documentation of ponage from across the South, legal records, personal testimonies, and contemporary analysis.

The exhibition drew record crowds and became one of the most visited special exhibitions in the museum’s history.

Educational institutions requested permission to use the photograph and curricula.

Several textbook publishers revised their reconstruction chapters to include discussion of ponage and debt bondage using the Bell Ree photograph as visual evidence.

Universities developed course units examining the photograph and the broader systems it represented.

The photograph also sparked calls for accountability and reparative justice, though these proved contentious and complex.

The discovery of the 1892 Bel Reef photograph raised profound questions about memory, justice, and historical accountability that extended far beyond the specific case of the Thornon family and their victims.

Dr.

Harrison found himself at the center of discussions about what contemporary society owes to descendants of those who suffered under ponage and other forms of postslavery oppression.

Patricia and other descendants of Bel Reeve workers formed an organization called the Bell Reeve Descendants Alliance to advocate for recognition and commemoration.

They worked with Louisiana state officials to place a historical marker at the former site of the plantation acknowledging what had occurred there.

The marker dedicated in June 2025 reads, “A Bell Reeve plantation operated here from 1834 to 1920.

Before the Civil War, over 150 people were enslaved here.

After slavery’s legal abolition in 1865, workers continued to be held in forced labor through debt penage, a system that trapped black workers and their families in bondage for decades.

This site represents both the brutality of slavery and its continuation through other means long after legal emancipation.

We honor the memory of those who suffered here and acknowledged the injustice they endured.

The Thornton family descendants who acknowledged their ancestors crimes faced difficult questions about what responsibility they bore.

Thomas Thornton, the descendant who had expressed shame, worked with the Believe Descendants Alliance to establish a scholarship fund for descendants of people who had been held in page.

He donated $50,000 of his own money and raised additional funds from other sources.

While some argued this was insufficient given the scale of the wealth extracted from forced labor, others saw it as a meaningful gesture of acknowledgement and attempted repair.

The photograph itself raised questions about how such images should be displayed and interpreted.

Some argued that showing images of people in bondage risked retraumatizing descendants and perpetuating dehumanizing representations of black suffering.

Others argued that evidence of historical injustice needed to be confronted directly, that sanitizing or hiding such images allowed people to avoid reckoning with the full reality of oppression.

The Smithsonian’s exhibition attempted to navigate this tension by displaying the photograph with extensive contextual information, including the stories of the individuals depicted in analysis of the systems that had trapped them, while also providing warnings about the disturbing content.

Dr.

Harrison’s research also prompted broader investigation into other cases of documented punage.

Historians began systematically searching archives for similar photographic or documentary evidence.

Several comparable cases were discovered in Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi.

Plantations and labor camps where workers had been held in forced labor well into the 20th century.

Each discovery added to the growing body of evidence showing that slavery’s legacy extended far beyond 1865.

The legal questions raised by these discoveries were complex.

Could descendants of P&age victims sue for compensation? Could the documented crimes lead to any contemporary legal accountability? Legal scholars generally concluded that the passage of time and the deaths of all direct perpetrators and victims made litigation impractical, but they argued that moral and historical accountability remained urgent.

The 1892 Believe photograph now resides in the permanent collection of the Smithsonian, preserved under museum quality conditions and accessible to researchers and the public.

It stands as one of the most significant pieces of documentary evidence about the continuation of forced labor after slavery’s legal abolition.

The image of the well-dressed Thornton family in the foreground and the shackled workers in the background captures a truth about American history that many would prefer to forget.

That the end of slavery was not clean or complete, that freedom had to be fought for repeatedly, and that the legacy of bondage extended far beyond what is commonly taught or acknowledged.

For Patricia and other descendants, the photograph provided something irreplaceable.

Proof of their ancestors experiences and validation of family stories that had been passed down but never documented.

Moses’s suffering was no longer just oral tradition.

It was historical record.

His survival and his family’s eventual escape represented not just survival, but resistance against a system designed to crush them.

The photograph forces viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about American history and about the systems of oppression that persisted long after they were supposedly abolished.

It serves as a reminder that justice delayed is justice denied and that the work of confronting historical injustice and building a more equitable society remains unfinished.

News

In 1923, the ghastly Bishop Mansion in Salem became the setting of the most brutal Hall..

.

| Fiction

Before we begin, I invite you to leave in the comments where you’re watching from and the exact time at…

(1912, North Carolina) The Ghastly Ledger of the Whitford Family — Wealth That Devoured Bloodlines

Welcome to this journey through one of the most disturbing cases recorded in the history of North Carolina. Before we…

The Creepy Family in a Brooklyn Apartment — Paranormal Activity and Unseen Forces — A Ghastly Tale

Welcome to this journey of one of the most disturbing cases in recorded history, Brooklyn, New York. Before we begin,…

Hidden in the attic, the Harris family found ghastly proof of a disturbing case from th..

.

| Fiction

Welcome to this journey through one of the most disturbing cases recorded in the history of Bowfort, South Carolina. Before…

In Tennessee, a family found ghastly VHS tapes… showing disturbing reunions recorded ba..

.

| Fiction

Welcome to this journey of one of the most disturbing cases in recorded history Tennessee. Before we begin, I invite…

The TERRIFYING Haunting of Karen Byers — A Ghastly Tale

Welcome to this journey of one of the most disturbing cases in recorded history, Appalachian, Virginia. Before we begin, I…

End of content

No more pages to load