Attention.

Welcome to this journey through one of the most disturbing cases recorded in Louisiana history.

Before we begin, I invite you to leave in the comments where you are watching from and the exact time you are listening to this narration.

We are interested in knowing to what places and at what moments of the day or night these documented accounts reach.

In 1850, the city of Baton Rouge stood as a testament to the peculiar institution that defined the antibbellum south.

Along the Mississippi River, grand plantations stretched like white monuments to wealth built upon human bondage.

It was in this world of contradictions that a story emerged which would haunt the records of East Baton Rouge Parish for generations to come.

The case first came to light in 1962 when a graduate student from Louisiana State University was researching property records in the basement of the old courthouse.

Among yellow documents and water stained ledgers, she discovered a collection of letters tied with a faded ribbon.

The correspondence dated between 1848 and 1851 would reveal a tragedy so profound that it challenged everything historians thought they knew about life in pre-Ivil War Louisiana.

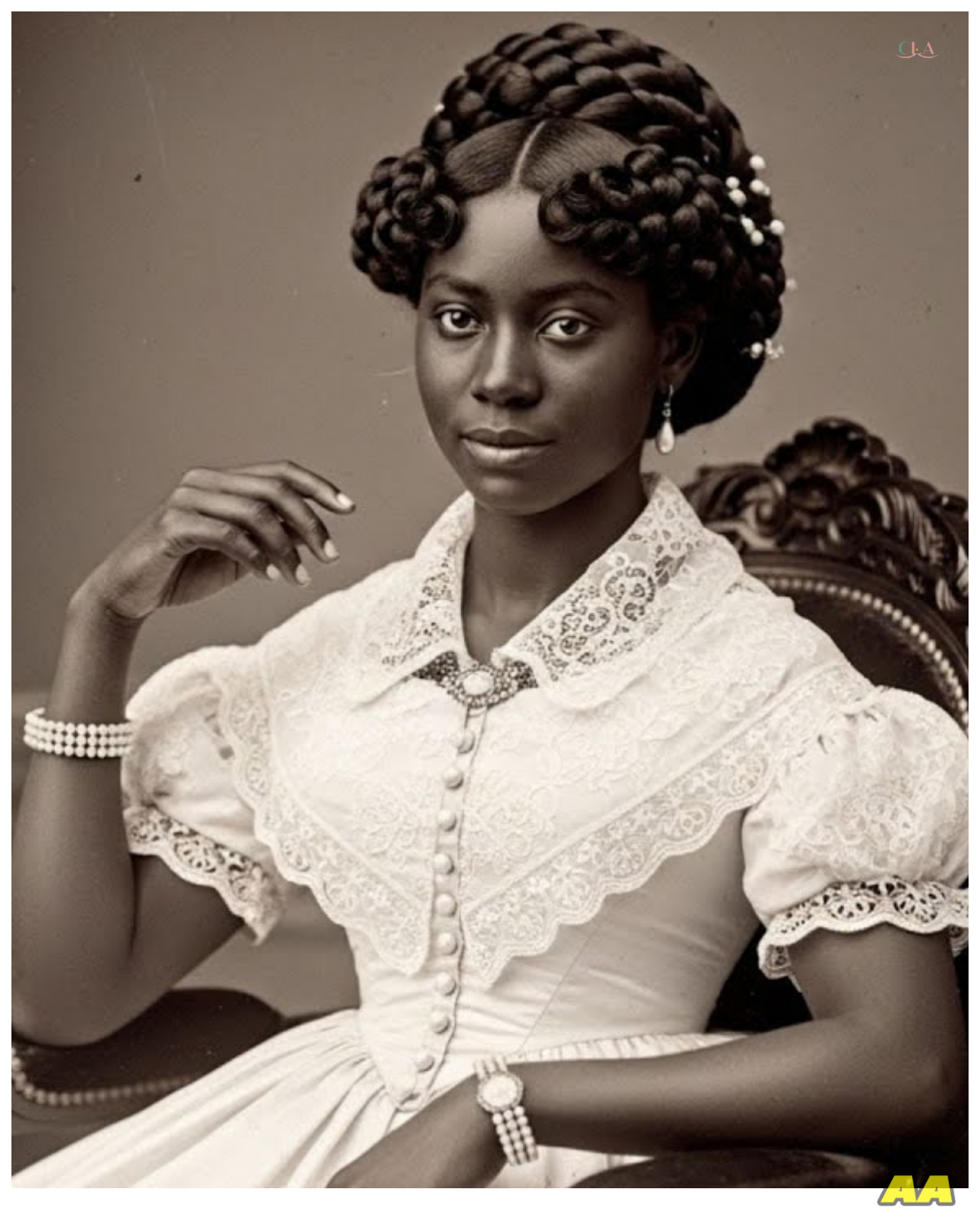

The letters spoke of a young woman whose beauty was said to be so extraordinary that it became both blessing and curse.

According to the documents, she was known simply as Amara, though official records would later reveal her full name as Amara Johnson.

Born into slavery on the Belfonte plantation, located 12 mi south of Baton Rouge near what is now the community of Gismar, she would become the subject of obsession, desire, and ultimately devastating tragedy.

The Bellfonte plantation belonged to Charles Bogard Whitmore, a man whose wealth derived from sugar cane cultivation and whose social standing in Baton Rouge society was considered unassalable.

The plantation house built in the Greek revival style popular among wealthy planters of the era sat on a slight rise overlooking the Mississippi River.

Its white columns and expansive galleries spoke of prosperity, while the quarters behind the main house told a different story entirely.

According to the discovered correspondence, Amara was born in 1832 to a woman named Sarah, who served as a house servant.

The father’s identity remained unrecorded, though whispers in the letters suggested possibilities that would have scandalized polite society.

What was documented, however, was that from an early age, Amara possessed a beauty that defied conventional descriptions of the time.

A journal entry found among the papers written by Margaret Whitmore, Charles’s wife, described the child in terms that revealed both admiration and unease.

The entry dated March 15th, 1845 noted that Amara had developed into a young woman whose appearance drew attention wherever she went.

Mrs.

Whitmore wrote of her concern about the girl’s effect on both the plantation’s male slaves and visiting white men.

Life at Bellifonte followed the rhythms common to sugar plantations of the era.

The main house bustled with activity as enslaved people maintained the elaborate lifestyle of the Witmore family.

Amara worked primarily in the house, initially helping in the kitchen and later serving as a ladies maid to Margaret Witmore.

According to the letters, she learned to read and write, an unusual circumstance that would later prove significant to the unfolding tragedy.

The social structure of Baton Rouge in 1850 was rigidly defined by race and class.

The white planter elite occupied the pinnacle of society.

Their wealth built upon the labor of enslaved people who existed in a world of legal non-personhood.

Free people of color, a distinct class in Louisiana, occupied an uncomfortable middle ground, while enslaved people remained at the bottom of the social hierarchy.

Within this system, Amara’s beauty created a dangerous anomaly that disrupted established norms.

The first indication of trouble appeared in a letter dated September 3rd, 1849, written by Margaret Witmore to her sister in New Orleans.

In it, she expressed growing concern about her husband’s behavior and mentioned that several young men from prominent Baton Rouge families had begun finding excuses to visit Bellfonte more frequently than propriety would suggest.

The letter hinted at conversations between Charles and other planters about Amara’s future, discussions that filled Margaret with dread.

What made Amara’s situation particularly precarious was the legal reality of her existence.

As enslaved property, she possessed no rights to refuse advances or protect herself from unwanted attention.

The letters revealed that by 1849 she had attracted the notice of several powerful men in the area, each viewing her as a potential acquisition for purposes that remained unspoken but clearly understood.

The correspondence suggested that Amara was not naive about her circumstances.

A fragment of what appeared to be her own writing discovered tucked between pages of a ledger revealed an intelligent and articulate young woman who understood the danger her appearance had brought upon her.

The fragment written in careful script spoke of sleepless nights and constant fear of watching the road that led to the plantation and dreading what each new visitor might bring.

If you’re enjoying the story and feel like helping the channel with any amount, please support us by clicking the thanks button and donating whatever you wish.

This really helps the channel keep posting new stories.

As autumn turned to winter in 1849, the situation at Bellfonte grew increasingly tense, Margaret Whitmore’s letters to her sister became more frequent and more desperate.

She wrote of her husband’s growing obsession and of heated arguments behind closed doors.

She mentioned that Charles had begun drinking heavily and that his behavior toward the household staff had become erratic and unpredictable.

The plantation itself seemed to reflect the growing tension.

Workers reported strange sounds at night and an atmosphere of unease that permeated daily life.

The overseer, a man named Thomas Bradford, noted in his reports that productivity had declined and that slaves seemed fearful and distracted.

He attributed this to rumors and gossip, but could not identify the source of the disturbance.

During this period, Amara’s mother, Sarah, became increasingly protective of her daughter, according to witness accounts recorded years later.

She began accompanying Amara everywhere and refused to allow her to work alone in any part of the house.

Other enslaved people on the plantation noted Sarah’s obvious fear, and her attempts to make Amara less visible by keeping her occupied in the kitchen rather than in public areas of the house.

The winter of 1849 brought several visitors to Belffonte.

Each arrival noted carefully in Margaret Whitmore’s increasingly frantic correspondence.

Among these visitors was Theodore Marshon, a wealthy planter from West Baton Rouge Parish, whose reputation for cruelty toward his enslaved people was well known throughout the region.

Another frequent guest was Jonathan Deo, a younger man whose family owned extensive holdings along False River.

Letters from this period revealed that these men were not visiting for social purposes.

Margaret Whitmore wrote explicitly about conversations she had overheard concerning the purchase of Amara.

Discussions that treated the young woman as a commodity to be evaluated and acquired.

The letters suggested that a sort of bidding war had developed among several potential buyers, each offering increasingly substantial sums for ownership.

What added another layer of horror to the situation was the revelation that Charles Whitmore was actively encouraging these negotiations.

Despite his wife’s obvious distress and his own household’s growing instability, he appeared to view Amomar’s desiraability as an opportunity for significant financial gain.

The letters indicated that he had set no minimum price and was willing to sell to whichever suitor offered the highest amount.

The spring of 1850 brought a development that would prove crucial to understanding the full scope of the tragedy.

Among the plantation’s correspondents was a letter from a free man of color named Marcus Tibido who lived in the TMA section of New Orleans.

The letter addressed directly to Amara suggested that the two had developed a relationship through intermediaries and that Marcus was attempting to purchase her freedom.

The letter revealed that Marcus had accumulated enough money to make a serious offer for Amara’s manu mission.

He wrote of plans to take her to New Orleans where, as a free woman, she could live under his protection.

The correspondence suggested that Amara had somehow managed to communicate with him, possibly through other enslaved people who traveled between plantations, and that she was desperate to escape her current situation.

However, Charles Whitmore’s response to this offer revealed the depth of his moral bankruptcy.

Rather than considering the humanitarian aspects of manumission, he saw Marcus’ proposal as simply another bid in the ongoing auction for Amara’s ownership.

Worse, he appeared to take pleasure in informing the other interested parties about this new competitor, using it to drive up the potential purchase price.

The situation reached a crisis point in early summer of 1850.

Margaret Whitmore’s letters from this period described a household in complete turmoil.

She wrote of violent arguments with her husband, of servants who jumped at every sound, and of an atmosphere so tense that even casual visitors commented on the obvious distress of everyone at Bellfonte.

During this time, Amara herself attempted to take control of her fate.

According to fragments of her writing discovered among the papers, she had begun planning an escape.

The documents suggested that she and several other enslaved people had identified a route through the swamplands that would take them toward New Orleans, where Marcus Tibido waited with money and promises of protection.

But the plantation was being watched too carefully for such a plan to succeed.

The overseer had been instructed to monitor Amara’s movements constantly, and the increased attention from potential buyers had made Charles Witmore paranoid about protecting his valuable property.

The letters revealed that escape attempts by enslaved people were not uncommon in the area, but the resources devoted to preventing Amara’s flight were extraordinary.

The tragedy that would define this case began on July 12th, 1850.

According to multiple accounts found among the papers, Theodor Marshon arrived at Belffonte with what he claimed was his final offer for Amara’s purchase.

The sum mentioned in the documents was staggering for the time period, equivalent to the cost of purchasing several prime field hands or enough to buy a small plantation.

What happened during Marshon’s visit remained unclear from the official records, but the aftermath was documented in horrifying detail.

Margaret Whitmore’s letter to her sister, written 3 days later, spoke of screams that echoed through the house and of blood that stained the floors of the main hallway.

She wrote of her husband’s complete breakdown and of Marshon’s hurried departure before dawn.

The local sheriff, Samuel Morrison, was called to investigate, but his official report was suspiciously brief.

He noted that Amara had attempted to flee the plantation and had been injured during her recapture.

The report mentioned no witnesses and provided no details about the nature of her injuries or the circumstances of her attempted escape.

The turseness of the official account suggested that powerful interests were working to minimize public knowledge of the incident.

What the official report did not mention was documented in private correspondence and witness accounts collected years later.

Multiple sources suggested that Amara had not been attempting to escape when the violence occurred.

Instead, the evidence pointed to an incident that took place within the main house itself involving Marshand and possibly Charles Witmore.

The aftermath of July 12th transformed Bellafonte Plantation into something resembling a tomb.

Margaret Witmore’s letters described a house where no one spoke above a whisper, and where the sound of footsteps on the wooden floors had become unbearable.

She wrote of sleeping with her bedroom door locked and of jumping at every unexpected noise.

Amara herself had disappeared entirely from the correspondence after this date.

The letters contained no mention of her recovery, her sale, or her continued presence on the plantation.

It was as if she had been erased from existence, leaving behind only the memory of trauma and the growing psychological deterioration of everyone who remained at Bel Fonte.

Charles Whitmore’s behavior in the weeks following the incident suggested a man consumed by guilt and fear.

Margaret’s letters described him as drinking constantly and talking to himself in his study late into the night.

She mentioned that he had dismissed several long-term employees and had forbidden anyone from entering certain parts of the house.

The plantation’s enslaved community also reflected the impact of whatever had occurred.

The overseer’s reports noted a dramatic decline in morale and productivity.

Several people had attempted to run away and those who remained seemed perpetually frightened.

The report suggested that rumors and stories were circulating among the slave quarters, but the exact nature of these stories was never recorded.

As summer turned to autumn, the situation at Belfonte continued to deteriorate.

Margaret Whitmore’s correspondence revealed that she had begun making arrangements to leave Louisiana permanently.

She wrote of plans to return to her family in Virginia and of her determination never to set foot on the plantation again.

Her letters suggested that she knew more about the events of July 12th than she was willing to commit to writing.

The final letter in the collection dated November 18th, 1850 provided the most disturbing revelation of all.

written by Margaret to her sister just before her departure from Louisiana.

It contained a confession that would haunt anyone who read it.

She wrote that she had finally learned the truth about what happened to Amara and that the knowledge had convinced her that some secrets were too terrible to be born.

In this final letter, Margaret revealed that Amara had not survived the events of July 12th.

She wrote that her husband and Marshand had disposed of the evidence of their crime in a way that ensured it would never be discovered.

The letter suggested that Amara’s body had been weighted down and dropped into one of the deep bayou that meandered through the plantation’s back acres, places where the dark water kept its secrets indefinitely.

But perhaps most chilling was Margaret’s revelation about the motive behind the violence.

According to her letter, the incident had not been the result of a failed escape attempt or even an act of sudden passion.

Instead, she suggested that Amara had been killed because she had threatened to expose something even more damaging than her own mistreatment.

The letter hinted that Amara had discovered evidence of illegal activities at Bellfonte, possibly involving the smuggling of enslaved people or financial fraud connected to the plantation’s operations.

Margaret wrote that her husband had been engaged in business dealings that would have ruined him if exposed, and that Amara had somehow gained knowledge that made her dangerous to these interests.

This revelation cast the entire tragedy in a new light.

Rather than being simply the victim of sexual violence or the target of obsessive desire, Amara had been eliminated because she posed a threat to a network of corruption that extended beyond the boundaries of Belffonte Plantation.

Her beauty had made her vulnerable, but her intelligence and awareness had made her a target for murder.

The documents suggested that Charles Whitmore never recovered from his crime.

Margaret’s letter mentioned that he had begun showing signs of mental deterioration, talking to empty rooms and claiming to hear voices that no one else could detect.

She wrote that he had become convinced that Amara’s spirit was haunting the plantation and that he could see her walking through the halls at night.

After Margaret’s departure, Bellfonte Plantation began its slide into decay.

Without proper management, the sugarcane fields became overgrown and the enslaved people were gradually sold off to pay mounting debts.

The main house, once a symbol of wealth and power, developed a reputation for being cursed, and finding overseers willing to work there became increasingly difficult.

Local records from the 1850s revealed that several people who worked at or visited Bellfonte during its final years reported disturbing experiences.

These accounts, dismissed at the time as superstitious nonsense, described the sound of crying that seemed to come from the walls themselves and the appearance of a young woman in white who vanished when approached directly.

Charles Whitmore died in 1853 under circumstances that raised questions among those who knew the full story.

The official cause of death was listed as heart failure.

But witnesses reported that he had been found in his study with a look of absolute terror frozen on his face.

Papers scattered around his desk suggested that he had been writing frantically before his death.

Though the content of his final writings was never made public, the plantation was sold at auction in 1854 to settle the massive debts that had accumulated.

The new owner, a businessman from New Orleans, attempted to restore the property to profitability, but found the task impossible.

Workers refused to stay.

Equipment mysteriously broke down and the house itself seemed to resist all efforts at renovation and improvement.

By 1857, Bellifonte Plantation had been abandoned entirely.

The house stood empty, its windows boarded up and its grounds slowly being reclaimed by the Louisiana wilderness.

Local residents began to avoid the area, claiming that strange sounds could be heard coming from the abandoned buildings and that anyone who ventured too close would experience an overwhelming sense of dread.

The Civil War brought additional chaos to the region and during the conflict, the abandoned plantation house was used briefly as a hideout by Confederate deserters and later by Union foraging parties.

Both groups reported unsettling experiences, describing voices that seemed to call out in the night and the feeling of being watched by invisible eyes.

After the war, the property changed hands several more times, but no one ever managed to establish a successful operation there.

Various attempts were made to tear down the main house and start fresh.

But construction workers consistently reported problems that defied rational explanation.

Tools would disappear, equipment would malfunction, and workers would simply abandon their jobs without explanation.

In 1868, a final attempt was made to investigate the property’s troubled history.

A researcher from Tulain University working on a project about abandoned plantations spent several weeks at Bellfonte examining records and interviewing local residents.

His final report filed with the university library concluded that the property was unsuitable for any form of development due to what he termed environmental factors that create an atmosphere of persistent unease.

The researcher’s report contained several disturbing details that had not appeared in previous accounts.

He noted that excavation work around the main house had uncovered fragments of clothing and personal items that seemed inconsistent with the property’s known history.

More troubling, he documented the discovery of what appeared to be restraints and other items that suggested the commission of violent crimes.

These findings prompted a more thorough investigation by local authorities, but the results were never made public.

The official report was classified and filed away, though rumors persisted that evidence had been found of multiple deaths at the plantation.

Deaths that had never been properly recorded or investigated.

By 1870, the Bellifonte property had acquired a reputation that ensured its permanent abandonment.

Local folklore had transformed the historical tragedy into something approaching legend with stories growing more elaborate and frightening with each telling.

Parents warned their children to stay away from the ruins and even adults rarely ventured near the site after dark.

The truth about Amara Johnson became lost in these accumulating layers of myth and speculation.

Her real story, the documented tragedy of a young woman whose beauty made her a target for violence and whose intelligence made her a threat to corruption, was overshadowed by ghost stories and supernatural explanations for the plantation’s troubled history.

It was not until 1962 when the graduate student discovered the hidden cache of letters that any serious attempt was made to reconstruct the actual events of 1850.

The documents provided the first reliable account of what had happened to Amara and revealed the extent of the conspiracy that had led to her death.

The student, whose name was recorded as Patricia Hendris, spent months transcribing and analyzing the letters.

Her preliminary report filed with Louisiana State University concluded that the documents represented authentic historical evidence of a crime that had been systematically covered up by powerful interests in antibbellum Baton Rouge society.

However, Hrix’s research was never completed.

According to university records, she abandoned the project in early 1963 and transferred to another school.

Her advisor noted that she had become increasingly disturbed by her research and had begun expressing fears about continuing the investigation.

The letters and documents she had discovered were returned to the courthouse archives where they remained largely forgotten.

The case might have ended there, lost among thousands of other historical documents gathering dust in basement storage rooms.

But in 1967, a construction project at the old courthouse required the relocation of archived materials.

During this process, workers discovered that the collection of letters about Amara Johnson had vanished entirely.

A thorough search of the archives revealed no trace of the documents.

The filing system showed that they had been checked out by someone with proper authorization, but the name on the request form was illeible, and no return date had been recorded.

Attempts to locate Patricia Hendris proved unsuccessful, as she seemed to have disappeared as completely as the letters themselves.

This final disappearance added another layer of mystery to an already complex case.

Some researchers suggested that the documents had been deliberately suppressed to protect the reputations of prominent Louisiana families whose ancestors might have been implicated in the original crime.

Others believed that the letters had simply been misfiled or destroyed through bureaucratic incompetence.

Regardless of what happened to the original documents, their brief emergence in 1962 had provided enough information to establish the basic facts of Amara Johnson’s story.

Subsequent researchers working with photocopies and transcriptions that Hrix had made were able to piece together a narrative that revealed one of the most disturbing cases of exploitation and murder in Louisiana’s antibbellum history.

The impact of this story extended far beyond the specific tragedy of one young woman.

It illuminated the systematic violence that underpinned the institution of slavery and demonstrated how beautiful enslaved women were particularly vulnerable to exploitation and abuse.

It also revealed how the legal system of the antibbellum south could be manipulated to cover up crimes when the victims were enslaved people and the perpetrators were wealthy white men.

Modern historians who have studied the case note that Amara’s story was probably not unique.

The conditions that led to her victimization existed throughout the slaveolding south and the mechanisms that allowed her murder to be covered up were standard features of the legal and social system.

What made her case unusual was not the crime itself, but the fact that documentary evidence survived to tell her story.

The physical location where these events occurred has long since been reclaimed by the Louisiana landscape.

The Bellfonte plantation house collapsed sometime in the early 20th century and the site is now covered by industrial development.

The bayus where Amara’s body was reportedly disposed of have been dredged and channelized for flood control.

No physical trace remains of the plantation or its tragic history.

Yet the story continues to resonate with those who study the hidden histories of American slavery.

Amara Johnson represents countless enslaved women whose beauty made them targets for violence and whose voices were silenced by a system that denied their humanity.

Her story serves as a reminder that behind the romanticized image of antibbellum plantation life lay a reality of systematic brutality and exploitation.

The legal framework that made Amara’s murder possible was not an aberration, but an integral feature of slave society.

Enslaved people had no legal standing to testify against their owners, no right to protection from violence, and no recourse when crimes were committed against them.

The system was designed to ensure that wealthy white men could commit virtually any act against their human property without fear of consequences.

What makes Amara’s case particularly tragic is the evidence that she was aware of her danger and actively seeking to escape it.

Her correspondence with Marcus Tibido revealed an intelligent young woman who understood her situation and was working to change it.

Her apparent discovery of illegal activities at Bellafonte suggested that she was not merely a passive victim, but someone who was fighting back against her oppression.

The fact that she was murdered not just for her beauty, but for her knowledge highlights the threat that intelligent enslaved people posed to the system that held them in bondage.

Plantation owners like Charles Witmore depended on maintaining absolute control over information and ensuring that their illegal activities remained hidden.

An enslaved person who gained knowledge of these activities represented a danger that had to be eliminated.

The cover up that followed Amara’s murder demonstrated the power of wealthy white men to manipulate the legal system and control public narrative.

Sheriff Morrison’s cursory investigation, the disappearance of official records, and the silence of potential witnesses all reflected a system designed to protect perpetrators rather than pursue justice.

The psychological toll on those involved in the crime was documented in the surviving correspondents.

Margaret Witmore’s letters revealed a woman traumatized by her knowledge of her husband’s actions.

While Charles Whitmore himself appeared to suffer a complete mental breakdown, even Theodore Marshand, who disappeared from the historical record after July 1850, was rumored to have died under mysterious circumstances within a few years of the incident.

The enslaved community at Bellfonte also bore the psychological scars of witnessing their powerlessness to protect one of their own.

The reports of declining morale and increased escape attempts suggested that Amara’s fate served as a stark reminder of the dangers they all faced.

The silence that surrounded her disappearance was enforced not just by white authorities, but by the knowledge that speaking out would only invite similar violence.

The broader community’s response to the tragedy reflected the moral corruption that slavery brought to all levels of society.

Neighbors and business associates who suspected what had happened chose to remain silent rather than confront powerful interests.

The conspiracy of silence that protected Charles Whitmore and Theodore Marshon was maintained by dozens of people who valued their own security more than justice for a murdered young woman.

The story of Amara Johnson also illuminates the particular vulnerabilities faced by enslaved women in the antibbellum south.

Their legal status as property meant that they could be bought, sold, and abused without recourse.

Those who possessed unusual beauty or intelligence faced additional dangers as these qualities made them valuable commodities in underground markets that trafficked in human suffering.

The fact that multiple wealthy men were competing to purchase amara revealed the existence of networks that specialized in the exploitation of enslaved women.

These networks operated with the knowledge and sometimes active participation of respected members of society, including plantation owners, merchants, and even law enforcement officials.

The disappearance of the documentary evidence in 1967 suggests that efforts to suppress this story continued well into the modern era.

The systematic removal of the letters from the courthouse archives was carried out by someone with both access and motivation to prevent the full truth from emerging.

This modern coverup indicates that the families and institutions implicated in the original crime retained enough power to protect their reputations even a century later.

The broader implications of Amara’s story extend beyond the specific crime to illuminate the institutional violence that characterized American slavery.

Her murder was not an isolated incident, but part of a system that routinely dehumanized and brutalized millions of people.

The mechanisms that allowed her killers to escape justice were the same mechanisms that protected slave owners throughout the South who committed similar crimes.

The research conducted by Patricia Hrix represented a brief moment when this hidden history almost came to light.

Her work promised to expose not just one historical crime, but the entire network of corruption and violence that sustained the peculiar institution.

The fact that her research was abandoned and the documents disappeared suggests that this exposure was perceived as threatening by those with the power to prevent it.

Modern scholars who have attempted to verify the details of Amara’s story have found that many of the supporting records have also disappeared or been destroyed.

Plantation records, court documents, and newspaper archives from the relevant period show suspicious gaps that make comprehensive research impossible.

This systematic destruction of evidence represents a continuing effort to suppress uncomfortable truths about American history.

The site of Belfonte Plantation, now covered by industrial development, serves as a metaphor for how modern society has literally and figuratively paved over the evidence of historical crimes.

The physical eraser of the plantation mirrors the documentary eraser of Amara’s story, both representing attempts to escape the moral responsibility that comes with acknowledging past injustices.

Yet, despite these efforts at suppression, the essential truth of Amara Johnson’s story survives in the fragments of evidence that remain.

Her brief appearance in the historical record serves as a testament to the countless enslaved people whose stories were never documented and whose suffering remains unagnowledged.

Her intelligence, beauty, and courage represent qualities that the system of slavery sought to destroy but could never completely eliminate.

The fact that we know anything about Amara’s story at all is due to the remarkable accident of documentary survival and the dedication of researchers like Patricia Hendris who recognize the importance of preserving these hidden histories.

Their work reminds us that behind every sanitized account of antibbellum plantation life lies stories of real people who suffered and died in ways that challenge our comfortable narratives about the past.

The ongoing mystery surrounding the disappearance of the original documents adds another dimension to this already complex case.

The questions raised by their vanishing suggest that the full truth about what happened at Belffonte Plantation in 1850 may never be known.

Yet, the fragments that remain provide enough evidence to reconstruct the basic outlines of a tragedy that represents one of the darkest chapters in Louisiana history.

As night falls over the industrial complex that now covers the former site of Bellfonte Plantation, one can only imagine what secrets lie buried beneath the concrete and steel.

The bayus that once flowed through the property have been channeled and controlled.

But somewhere in their dark waters may rest the physical evidence of crimes that powerful people worked so hard to conceal.

The story of Amara Johnson serves as a reminder that history is written by the victors, but sometimes the voices of the victims managed to survive despite all efforts to silence them.

Her brief appearance in the documentary record, though ultimately suppressed, provides a window into a world of systematic brutality that shaped American society for generations.

Perhaps most disturbing is the realization that the mechanisms that allowed Amara’s murder to be covered up were not exceptional, but routine features of a society built on the systematic dehumanization of enslaved people.

Her story reveals not just one crime, but an entire system of violence that was considered normal and acceptable by those who profited from it.

The psychological and social consequences of this violence extended far beyond its immediate victims to corrupt the entire society that permitted and protected it.

The fear, guilt, and moral degradation experienced by perpetrators like Charles Witmore and witnesses like Margaret Witmore demonstrated that slavery brutalized everyone it touched, even those who seemed to benefit from it.

In the end, the story of Amara Johnson stands as both historical documentation and moral challenge.

It forces us to confront uncomfortable truths about the foundations of American society and to acknowledge the human cost of systems that treat people as property.

Her voice emerging briefly from the silence of history before being suppressed once again reminds us that behind every statistic and every sanitized historical narrative lies a real person who lived, suffered, and died.

The beauty that made Amara a target, the intelligence that made her dangerous, and the courage that led her to fight for her freedom, represent qualities that the system of slavery sought to destroy but could never completely eliminate.

Her story, though fragmentaryary and suppressed, serves as a testament to the resilience of the human spirit, even in the face of overwhelming oppression.

And perhaps in some small way, telling her story now serves as a form of justice for a young woman whose life was cut short by greed, violence, and the systematic denial of her humanity.

Though we may never know the full truth about what happened at Belfonte Plantation in 1850, we can at least ensure that Amara Johnson’s name and story are not entirely forgotten.

The silence that once protected her killers has been broken, if only briefly.

The cover up that lasted for over a century has been exposed, even if the full evidence remains hidden.

And somewhere, perhaps in the dark waters of a Louisiana bayou, the truth waits to be discovered by those brave enough to seek it.

Until today, no one knows exactly what happened that night in July 1850 at Bellfonte Plantation.

The official records remain sealed or lost.

The witnesses have long since passed away, and the physical evidence lies buried beneath layers of Louisiana soil and industrial development.

What we do know is that a young woman named Amara Johnson lived, suffered, and died in a system designed to deny her very humanity.

Her story, though incomplete and suppressed, represents the experiences of countless enslaved people whose voices were silenced by violence and whose stories were erased by those who profited from their oppression.

The letters discovered in 1962 provided a brief glimpse into this hidden world before vanishing into the same darkness that claimed their subject.

Patricia Hendris, the graduate student who first brought Amara’s story to light, disappeared as completely as the documents she had transcribed, leaving behind only fragments of evidence and unanswered questions.

Perhaps this is fitting.

In a society that worked so hard to erase the humanity of enslaved people, the fact that any trace of Amara’s story survived at all represents a small victory against the forces of historical amnesia.

Her name, her intelligence, her beauty, and her courage managed to break through more than a century of silence to remind us that behind every statistic about slavery lies a real person who lived and died.

The industrial complex that now covers the former site of Bellfonte Plantation operates 24 hours a day.

Its machinery drowning out any sounds that might echo from the past.

Workers report nothing unusual.

No voices in the night or unexplained phenomena.

The bayou have been channeled and controlled, their dark waters diverted for more practical purposes.

Yet sometimes late at night when the machinery falls silent for maintenance, local residents claim they can still hear something carried on the Louisiana wind.

A sound like crying, they say, or perhaps like singing.

A voice that seems to come from everywhere and nowhere, calling out across the years for justice that never came.

And perhaps in the end, that is enough.

Perhaps the simple act of remembering, of refusing to let Amara Johnson’s story disappear entirely, serves as its own form of justice.

Her voice, silenced by violence and suppressed by power, has found a way to speak across the centuries to remind us that some truths cannot be buried forever.

The beautiful slave of Baton Rouge, whose tragic life and death illuminated the darkest corners of American history, has finally found her voice.

And in that voice, we hear not just her story, but the stories of all those who suffered in silence, whose names we will never know, whose graves we will never find.

Some doors once opened can never be completely closed again.

Some voices once heard can never be entirely silenced.

And some truths, no matter how deeply buried, will always find a way to rise to the surface.

The story of Amara Johnson is over.

But perhaps in some way it is also just

News

✈️ U.S. F-15 FIRST STRIKE — ALLEGED CARTEL DRUG LAB ERASED IN SECONDS AS SKY ERUPTS IN A BLINDING FLASH ✈️ What officials described as a precision operation turned the night into daylight, with jets screaming overhead and a suspected production site reduced to smoking rubble in moments, sending a shockwave across the region and a message that the airspace above is no safe haven for hidden empires 👇

The Last Fortress: A Shocking Revelation In the heart of the Mexican jungle, Diego stood at the entrance of the…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: FBI & ICE SHATTER ALLEGED TRUCKING NETWORK WITH SOMALI TIES — 83 ARRESTED, $85M IN CASH AND WEAPONS STACKED AS EVIDENCE 🚨 Before sunrise, federal agents swept through depots and dispatch offices, hauling out duffel bags of currency and seizing firearms while stunned neighbors watched a logistics operation authorities claim was hiding a sprawling criminal enterprise behind everyday freight routes 👇

The Shadows of the Ghost Fleet In the heart of the Midwest, where the snow fell like a blanket over…

🚨 FBI & ICE STORM GEORGIA “CARTEL HIDEOUT” — GRENADE LAUNCHER DISCOVERED AND $900K IN DRUGS SEIZED IN A DAWN RAID THAT SHOCKED THE BLOCK 🚨 What neighbors thought was just another quiet morning exploded into flashing lights and tactical vests as agents swept the property, hauling out weapons and evidence while officials described a months-long investigation that culminated in a swift, coordinated takedown 👇

The Unraveling of Shadows: A Tale of Betrayal and Redemption In the heart of Jackson County, Georgia, the air was…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: DEA & FBI CRUSH ALLEGED CARTEL TRUCKING EMPIRE — HIDDEN ROUTES MAPPED, DRIVERS DETAINED, AND MILLIONS STACKED AS EVIDENCE 🚨 Before sunrise, highways turned into a grid of flashing lights as agents intercepted rigs, cracked open trailers, and traced coded dispatch logs, revealing what officials describe as a logistics web hiding in plain sight behind ordinary freight lanes 👇

The Fall of Shadows: A Cartel’s Empire Exposed In the dimly lit corridors of power, where shadows danced with deceit,…

🚢 U.S. NAVY TRAPS SINALOA CARTEL’S ALLEGED $473 MILLION “DRUG ARMADA” AT SEA — AND THE HIGH-STAKES STANDOFF UNFOLDS UNDER FLOODLIGHTS AND ROTOR WASH 🚢 Radar screens lit up, cutters boxed in fast boats, and boarding teams moved with clockwork precision as authorities described a sweeping maritime interdiction that turned open water into a chessboard, stacking seized cargo on deck while prosecutors hinted the ripples would travel far beyond the horizon 👇

The Abyss of Deceit: A Naval Reckoning In the heart of the Caribbean, where the turquoise waters glimmered under the…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: DEA & FBI DESCEND ON MASSIVE TEXAS LOGISTICS HUB — 52 TONS OF METH SEIZED AS 20 POLITICIANS ALLEGEDLY TIED TO A SHADOW NETWORK ARE THRUST INTO THE SPOTLIGHT 🚨 What began as a quiet federal probe detonated into a sweeping raid of warehouses and boardrooms, with agents hauling out towering stacks of evidence while stunned insiders whisper that the real shockwave isn’t just the drugs — it’s the powerful names now facing intense scrutiny 👇

Shadows of the Underground: The Texas Cartel Unveiled In the heart of Texas, where the sun sets over sprawling landscapes,…

End of content

No more pages to load