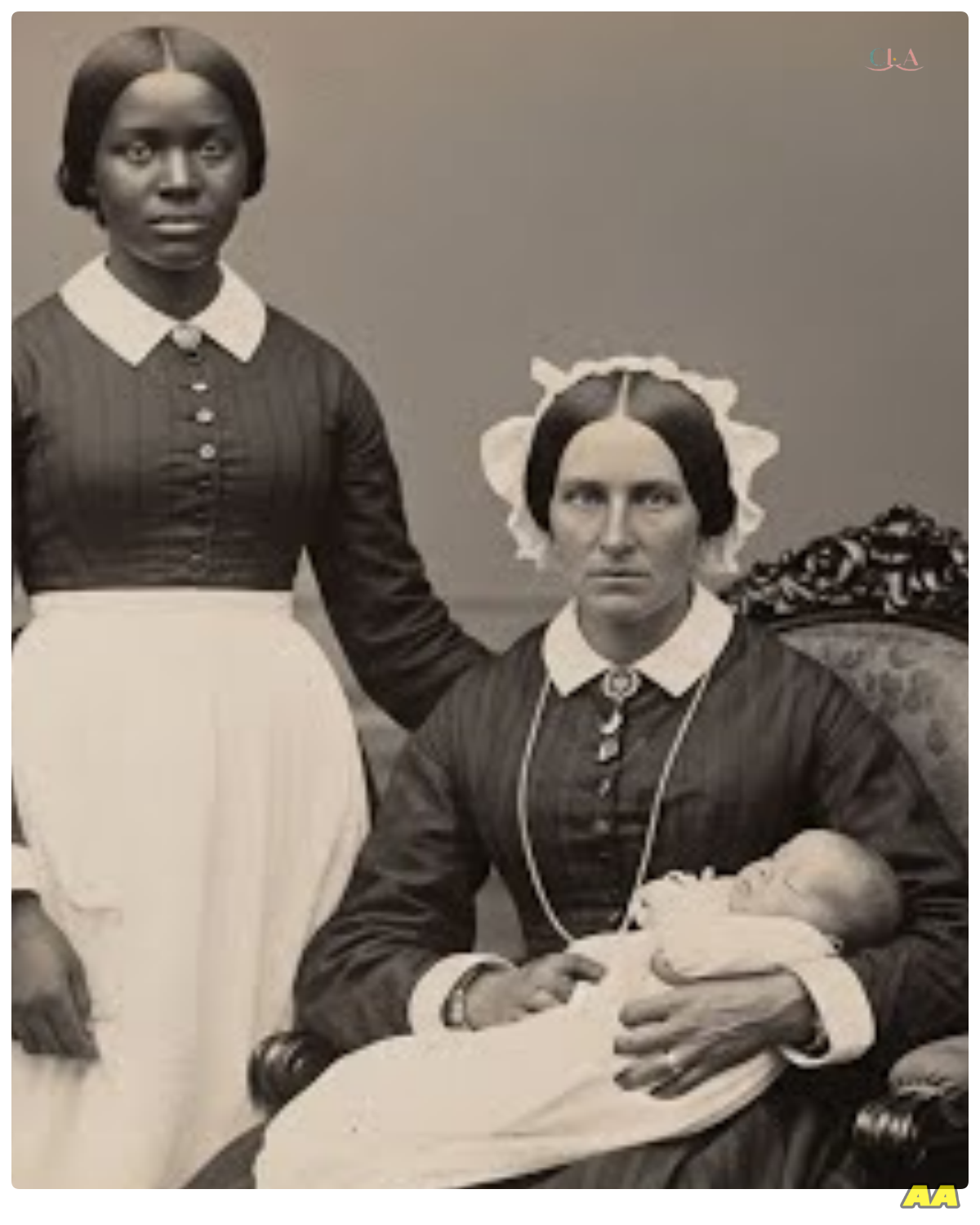

The Slave Who Gave Birth to 10 Children.

None Allowed to Call Her “Mother”

Welcome to one of the most disturbing cases recorded in the history of Charleston.

Before we begin, I invite you to leave in the comments where you are watching from and the exact time you are listening to this narration.

We are interested to know which places and what times of day or night these documented accounts reach.

It was December 19th, 1843 when the first documented reference to Ruth Mayfield appeared in the parish records of St.

Philip’s Church in Charleston, not as a baptism or marriage, but as an inventory item.

One female negro, approximately 23 years of age, valued at $800.

Her name appeared only in the margin, written in a different hand than the official recordkeeper, Ruth.

Just Ruth.

The surname Mayfield would come later, not by choice, but by ownership.

The Preston Mayfield estate stood 3 mi outside of Charleston proper along the Ashley River.

The property dated back to 1796 when cotton still promised unlimited wealth to those willing to extract it through the labor of others.

By 1843, the grandeur had faded somewhat.

The white columns of the main house showed cracks near their bases.

The outuildings, slave quarters, stables, and storage sheds leaned slightly, as if exhausted by the weight of what occurred within their walls.

The Mayfield ledgers, discovered during a 1962 renovation of the Charleston County Records Office detail every business transaction of the estate from 1839 to 1852.

Among these entries, Ruth appears with increasing frequency.

her purchase on December 19th, 1843.

Her first pregnancy recorded in April 1844.

By March of 1851, she had given birth nine times.

Her 10th birth would be recorded in October of that same year.

What makes the Mayfield case so disturbing is not these cold facts alone, but what emerged when a history student named Margaret Harlow began examining correspondence between Elellanena Mayfield, the plantation mistress, and her sister in Baltimore.

These letters, held in a private collection until 1965, reveal a household practice so psychologically devastating that it defies comprehension, even in an era characterized by countless inhumanities.

The children born to Ruth were raised in the main house not as her children but as Elellanena’s.

And Ruth was forced to serve as their nursemaid, forbidden from acknowledging her maternal connection.

Each time one of her children called Elellanena mama, Ruth was required to be present.

Each time one of her children passed her without recognition in the hall, she was expected to show no emotion.

The emotional architecture of this arrangement, this deliberate psychological torture forms the center of this documented case.

The records show Ruth’s first child, a boy, was born in January 1845.

He was given the name Thomas.

In Elellanena’s letters to her sister, she wrote about my sweet little Thomas, who had arrived after much anticipation.

No mention is made of Ruth except as the wet nurse who proves adequate at her duties.

According to household accounts, Ruth was moved from fieldwork to the main house 3 weeks before the birth, suggesting a deliberate plan was already in place.

7 months after Thomas’s birth, Elellanena wrote to her sister, “The arrangement with the nurse proceeds excellently.

She shows no improper attachment to the child and responds promptly when I call for him.

Preston believes our method is most sensible for maintaining proper order.

The letter continues with mundane household matters as if the psychological violence being perpetrated was nothing more remarkable than the changing of linens or the ordering of supplies.

By 1847, Ruth had given birth to a second child, a girl named Sarah.

Elellanena’s correspondence becomes more explicit.

We have established a most effective system.

The nurse understands that any maternal displays toward either child will result in immediate separation.

Her to be sold down river, the children to remain here under my care.

You would be amazed how well behavior can be controlled when the stakes are made perfectly clear.

The Preston Mayfield estate employed 23 enslaved persons in 1848, according to tax records.

Interviews conducted in the 1930s with descendants of those who had been enslaved at neighboring plantations suggest that Ruth’s situation was known beyond the Mayfield property.

Eliza Johnson, aged 94 when interviewed in 1936, recalled her grandmother speaking of the woman who was mother to the white lady’s children and how it turned her quiet as a shadow, seeing her own flesh, walking about not knowing her.

County census records from 1850 show that by then Ruth had given birth to seven children.

All were listed as belonging to Preston and Elellanena Mayfield.

All were described as white.

Ruth’s children, it seems, were also Preston’s.

Yet this biological fact remained publicly unagnowledged and privately, ruthlessly enforced against recognition.

The children grew up in the presence of their mother, yet without knowledge of her.

They issued commands to her.

They sometimes complained about her, and with each interaction, Elellanena watched for any sign of maternal acknowledgement.

According to Elellanena’s letters, Ruth attempted to escape only once in the spring of 1849.

She was caught before reaching the Charleston city limits and returned to the plantation.

The punishment, as described clinically in Eleanor’s correspondence, involved forcing Ruth to stand silently in the corner of the nursery while Elellanena explained to Ruth’s five eldest children that the nurse had tried to abandon them because she found them troublesome.

The children, aged between 2 and 4 years, were encouraged to express their hurt feelings to Ruth, who was forbidden from responding.

The discipline has proven most effective.

Elellanena wrote two weeks later.

She performs her duties with perfect detachment.

Now, I believe the lesson has been thoroughly learned.

When the Mayfield House was sold in 1958, and its attic cleared, workers discovered a small package tucked beneath the floorboards near what had been the servant staircase.

Inside was a piece of cloth containing 10 small items.

A button, a chicken bone polished smooth, a piece of blue ribbon, a small stone, a dried flower, a thimble, a broken shell, a child’s tooth, a lock of hair tied with thread, and a handcarved wooden star.

No documentation accompanied these items.

Their significance can only be inferred.

Doctor Katherine Wells, who studied the Mayfield case for her 1967 dissertation at the University of Virginia, has suggested that this collection represented Ruth’s private motherhood, small tokens connected to each of her children, hidden away where she might access them unseen.

The placement near the servant stairs would have allowed Ruth brief moments with these tokens while moving between floors of the house.

It represents doctor Wells wrote a form of psychological resistance to an almost unimaginable cruelty maintaining maternal connection through secret symbols when direct acknowledgement was forbidden.

The children’s lives are documented through the normal records of 19th century Charleston society.

school registrations, church confirmations, business transactions, eventually marriages and children of their own.

They appear on paper as unremarkable members of Charleston’s antibbellum society.

None of the historical record suggests they ever learn the truth about their parentage.

Ruth disappears from the documentary record after 1853.

The 10th birth, recorded in October 1851, is her last appearance in the Mayfield household accounts.

No death certificate exists.

No burial record, no sale document.

In her final letter that mentions Ruth, dated February 1853, Elellanena writes only, “The nurse has been removed from the household.

The younger children have been told she was called away to assist relatives.

They accepted this explanation without question, as they have never been particularly attached to her.

The clinical coldness of this final dismissal of a woman who had been subjected to a decade of psychological torture is perhaps the most chilling aspect of the entire case.

The casual erasure of both her presence and her immense suffering suggests the complete success of the system designed to deny her humanity.

In 1968, Dr.

Wells attempted to locate descendants of Ruth’s children to inform them of their true lineage.

The Mayfield family descendants refused to participate in the study, and legal challenges prevented the publication of Dr.

Wells full findings.

Her research materials were sealed by court order until 2018, by which time all immediate descendants would be deceased.

When contacted by our research team, the University of Virginia Special Collections Library confirmed that the wells materials remain sealed with access restricted by terms of a confidential legal settlement.

The Mayfield House itself was destroyed by fire in 1973.

The cause was never determined.

Local newspaper accounts described the blaze as particularly intense with the structure collapsing inward as if consumed from its center.

Nothing remained but the stone foundation and parts of the brick chimneys.

The property remained undeveloped for decades with locals describing it as uncomfortable ground.

Housing development finally began on the site in 1997, though construction workers reported unusual problems throughout the building process.

Tools disappearing, unexplained cold spots, and a persistent smell of smoke that engineers could never trace to a source.

Residents of the homes built on the former Mayfield property have reported few issues, though several have mentioned that children seem reluctant to play in certain areas of their yards.

When interviewed for a 1999 local history project, one homeowner mentioned that her four-year-old daughter refused to play near the old oak tree at the edge of their property.

When asked why, the child reportedly said, “That’s where the quiet lady stands and watches.

” The story of Ruth Mayfield, a woman systematically denied her identity as a mother while being forced to witness her children’s lives from a position of servitude, represents a particularly cruel refinement of the already inhumane institution of slavery.

In 1862, during the second year of the Civil War, Preston Mayfield Jr.

, Ruth’s eldest son, though he never knew it, wrote a letter to his fianceé expressing his willingness to defend our way of life against northern aggression.

The letter preserved in the Charleston Historical Society archives contains this passage.

I fight not merely for property or politics, but for the natural order of relations between the races, which God in his wisdom has established for the benefit of all.

The psychological architecture of this arrangement stands as testament to slavery’s fundamental project.

Not just the exploitation of labor, but the deliberate destruction of human bonds to reinforce power.

The servants content in their place, the masters benevolent in their governance.

The profound tragedy of these words written by a man in defense of the very system that had stolen his mother from him cannot be overstated.

He had been so thoroughly indoctrinated into the mythology of racial hierarchy that he was willing to die to preserve it, never knowing how personally it had distorted his own existence.

Dr.

Wells in the published portion of her research wrote, “The case of Ruth Mayfield represents the logical conclusion of slavery’s fundamental premise that some human beings can be fully owned by others.

When ownership extends not just to labor but to identity itself, we see the full psychological horror of the institution revealed.

Ruth was denied not just freedom of movement or freedom of choice, but the most basic human connection, that between mother and child.

Her story stands as perhaps the clearest illustration that slavery’s greatest violence was not physical, but psychological.

the systematic destruction of the self.

In 1969, a former domestic worker came forward claiming to be the granddaughter of someone who had worked in a neighboring household to the Mayfields.

According to her account, passed down through oral history, Ruth had not disappeared in 1853, but had been confined to the attic of the Mayfield house after attempting to tell one of her children the truth.

The claim could not be verified and the woman declined to be formally interviewed after receiving what she described as threatening communications following her initial statement.

The last official document connected to the Mayfield case is a 1971 court ruling sealing all records related to Dr.

Wells’s research until 2018.

The ruling issued by Judge William Harmon of the Charleston County Court cited potential distress to living descendants and the lack of conclusive evidence regarding certain claims as justification.

Dr.

Wells died in 1986, her full research findings never published.

When our research team visited the former Mayfield property in November of last year, we found a suburban development of comfortable homes.

An unmarked stone memorial stands at the entrance to the neighborhood placed there by the developers as part of a compromise with local historians who had advocated for formal recognition of the site’s history.

The homes sell for between $300 and $500,000.

None of the current residents we spoke with were aware of the property’s history.

The stone bears no inscription, no mention of Ruth, no acknowledgement of the 10 children born of her body who were forbidden to call her mother.

Just smooth granite weathering slowly in the Carolina sun.

Perhaps fitting for a woman whose identity was systematically erased, whose maternal connections were denied, whose very existence was reduced to entries in household accounts.

Somewhere in America today, descendants of those 10 children live their lives, unaware that their lineage traces back not just to Preston and Elellanena Mayfield, but to a woman named Ruth, who preserved buttons and ribbons and locks of hair as the only expression of motherhood permitted to her.

They are living embodiment of a heritage deliberately obscured.

their very existence testimony to both the endurance of human bonds and the brutal systems designed to sever them.

As we conclude this documentary account, we are left with questions rather than closure.

What psychological toll did this arrangement take on the children raised by their biological mother, yet prevented from knowing her as such? Did any of them sense the truth intuitively, feeling connections they couldn’t articulate? What thoughts occupied Ruth’s mind as she moved silently through the house, tending to children who were hers but could never know her? These questions echo across time, unanswered and perhaps unanswerable.

The silence at the center of this story, Ruth’s enforced silence, speaks volumes about the systems designed to maintain power through the destruction of human connection.

In that silence lies the true horror of the Mayfield case.

Not a supernatural presence or a violent act, but the deliberate sustained eraser of the most fundamental human bond.

A mother forbidden to mother.

Children forbidden to know their origin.

And a woman whose resistance took the form of small treasures hidden beneath the floor.

each one a silent testament to love that could not be expressed but refused to be extinguished.

In 1966, three years before the controversial testimony about Ruth’s possible confinement, a construction worker renovating the former caretaker’s cottage on the edge of the Mayfield property discovered a small tin box buried beneath the hearthstones.

Inside was a journal, its pages brittle and water damaged, with most entries rendered illeible by time and the elements.

The journal was submitted to the Charleston Historical Society, but was deemed of limited historical value due to its poor condition and returned to the property owners who reportedly discarded it.

However, according to the construction worker statement given in 1972 to a graduate student researching antibbellum Charleston, several pages contained legible text that appeared to document observations of the Mayfield children.

The worker James Tanner recalled phrases like the youngest boy has her eyes exactly and today s reached for me before catching herself.

Tanner believed the journal might have belonged to someone who knew Ruth’s secret, possibly another household servant or even a member of the extended Mayfield family who silently witnessed the arrangement.

The possibility that someone within the household recognized the truth but remained silent adds another layer of complexity to the Mayfield case.

How many others observed this psychological torture without intervention? The complicity of silence extended beyond the immediate perpetrators, creating an environment where such cruelty could persist unchallenged for over a decade.

Dr.

Amelia Richardson, professor of psychology at Emory University, has studied the Mayfield case through the limited available records.

In her 2008 paper, Maternal Deprivation as psychological control in antibbellum slave households, she writes, “The Mayfield case represents an extreme example of what was likely a more widespread practice than historical records acknowledge.

By forcing enslaved women to care for their biological children as servants rather than mothers, slave owners created a particularly insidious form of psychological control, one that simultaneously appropriated reproductive labor while destroying the fundamental human connection of maternity.

Richardson’s research suggests that similar arrangements existed on other plantations, though perhaps not with the same systematic implementation as the Mayfield case.

The practice served multiple purposes within the twisted logic of slavery.

It reinforced the complete ownership of enslaved women’s bodies and reproductive capacity.

It provided household labor with built-in emotional control mechanisms, and it prevented the formation of family bonds that might challenge the authority structure of the plantation.

Church records from St.

Phillips’s Parish show that all 10 of Ruth’s children were baptized between 1845 and 1852.

Each baptismal record lists Preston and Elellanena Mayfield as the parents.

The officiating minister, Reverend Thomas Wentworth, was a frequent dinner guest at the Mayfield estate.

According to Elellanena’s correspondence with her sister, in a sermon delivered in 1848, preserved in the church archives, Reverend Wentworth spoke on the divine ordering of society and the Christian duty of those placed in authority to provide guidance to their dependents.

He specifically praised unnamed parishioners who had taken extraordinary measures to ensure that children of unfortunate circumstance are raised with all the advantages of Christian civilization.

The coded language almost certainly referred to the Mayfield arrangement cloaking the psychological cruelty and religious justification.

His complicity in recording these baptisms with full knowledge of the children’s true parentage represents yet another level of institutional support for the deception.

The 10th and final child born to Ruth in October 1851 was a girl named Mary.

According to Elellanena’s letters, this child was noticeably darker in complexion than her siblings, suggesting that Preston may not have been the father.

This deviation from the established pattern appears to have created a crisis within the household.

Elellanena’s letters from this period become erratic with references to securing the family’s reputation and addressing the nurse’s moral lapse.

Mary disappears from household records by 1852.

No death certificate exists, but an entry in the Mayfield household accounts shows a payment to Dr.

James Harwood in November 1851 for medical services and discretion regarding household matter.

The implication that the child may have been eliminated due to her appearance is too disturbing to dismiss, though no concrete evidence exists to confirm this suspicion.

It was shortly after this period that Ruth herself vanishes from the documentary record supporting the theory that the crisis precipitated by Mary’s birth led to Ruth’s removal from the household.

Whether through sale, confinement, or worse, remains unknown.

The psychological impact on Ruth can only be imagined.

To give birth 10 times and to be denied the right to mother any of those children, to watch them grow, speaking with accents different from her own, absorbing values and beliefs that justified her enslavement, to clean their scraped knees, to serve their meals, to wash their clothes, all while maintaining the fiction that she was merely a servant with no deeper connection.

The daily psychological violence of this arrangement exceeds even the considerable physical cruelties of slavery.

Doctor Richardson’s research points to scattered evidence of Ruth’s resistance within this seemingly hopeless situation.

The collection of small items connected to each child represents one form of resistance.

Maintaining maternal connections in secret when they were forbidden in public.

Elellanena’s letters contain occasional references to Ruth being corrected for improper familiarity with the children, suggesting moments when the performance of detachment faltered and Ruth’s maternal instincts broke through the enforced facade.

In one particularly revealing passage from 1847, Elellanena writes to her sister, “We had an incident yesterday when Thomas fell from the garden wall and cut his forehead.

Before I could reach him, the nurse had gathered him up and was speaking to him in that language they use among themselves.

Preston witnessed this display and administered correction immediately.

They’ve restricted her access to Thomas for a fortnight to ensure the lesson is properly learned.

This brief glimpse into Ruth’s momentary lapse speaking to her injured child in Gula, the Creole language spoken by enslaved people in the Carolina Low Country, reveals both her instinctive maternal response and the harsh consequences of such natural human behavior within the Mayfield system.

that she would risk punishment to comfort her injured child speaks to the powerful persistence of maternal bonds even under the most extreme conditions of psychological oppression.

The descendants of the Mayfield children unknowingly also the descendants of Ruth spread across the United States in the generations following the Civil War.

Census records and genealogical databases trace their migration to cities like Atlanta, Richmond, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Many achieved middle and upper middle class status with professions in medicine, law, education, and business.

In 2009, a historian working on an unrelated project discovered correspondence between Elellanena Mayfield’s nephew, William Cartwright, and a cousin in Philadelphia dated 1873, 20 years after Ruth’s disappearance from the record.

In this letter, Cartwright mentions visiting the former Mayfield plantation, then owned by another family, and being disturbed by rumors that Aunt Elellanena’s former nurse was still living in a remote cabin on the edge of the property, aged beyond her years, and speaking to no one.

This tantalizing reference suggests the possibility that Ruth survived long after her official disappearance from the Mayfield records, perhaps living in isolation on or near the property where her children had grown up.

If true, she would have witnessed the Civil War, emancipation, and the early years of reconstruction, profound social transformations that came too late to restore her maternal connections.

The Cartwright letter represents the last known historical reference that might pertain to Ruth.

If she did survive into the 1870s, she would have been in her 50s, not elderly by modern standards, but aged beyond her years through suffering and hardship.

The letter offers no clue as to how long she might have remained in that isolated cabin, or what eventually became of her.

In the absence of conclusive historical evidence, Ruth’s ultimate fate remains one of the many painful silences surrounding this case.

Like so many enslaved individuals, her life was documented primarily through the lens of property records and the correspondence of those who claimed ownership of her.

Her thoughts, feelings, and experiences beyond what can be inferred from these biased sources remain largely inaccessible to modern researchers.

Perhaps the most telling artifact in the entire Mayfield case is not a document or letter, but the collection of small treasures found beneath the servant’s staircase.

Each item, the button, the ribbon, the polished bone, the lock of hair, represents an act of defiance so subtle it escaped detection, yet so profound it preserved the connection between mother and child when all external expression of that bond was forbidden.

Doctor Wells in the conclusion to her unpublished dissertation wrote, “The collection of keepsakes hidden beneath the Mayfield House floorboards represents a form of resistance history has only recently begun to recognize the maintenance of human dignity and connection in circumstances designed to destroy both.

” Ruth created through these tokens a shadow motherhood that existed alongside but hidden from the fiction maintained by the Mayfield household.

Each object connected her to a child who could not know her, preserving bonds that the institution of slavery actively worked to sever.

The psychological sophistication of this form of resistance, creating symbolic connections when literal ones were forbidden, speaks to the profound resilience of the human spirit under even the most dehumanizing conditions.

Ruth, denied the right to openly mother her children, created an alternative motherhood through these small talismans, each one representing a child who could not acknowledge her.

The blue ribbon might have fallen from Sarah’s hair during play.

The polished chicken bone might have been a toy Ruth secretly created for her youngest son.

The button might have come from Thomas’s first formal jacket.

Each item, insignificant in material value, represented an irreplaceable connection to children who were simultaneously present in her daily life, yet irrevocably separated from her by the brutal social fiction of the Mayfield household.

In 1959, when the small bundle of keepsakes was discovered during renovation of the Mayfield House, the items were photographed, but considered of minimal historical importance.

The photograph preserved in the Charleston County Historical Society archives shows objects arranged on a white cloth, small worn items that would appear to be junk to those unaware of their context.

The collection was eventually lost with no record of where the items ended up after documentation.

This loss represents yet another eraser in Ruth’s story.

The physical evidence of her secret resistance disappearing just as her presence in her children’s lives was systematically obscured.

The pattern of erasia continues across generations with each loss of documentation further obscuring the already faint historical traces of her existence.

In 2018, when the sealed records of doctor Wells research were finally opened according to the court order, researchers discovered that many of the most sensitive documents were missing, whether removed legally through subsequent court actions or taken through unauthorized means.

The absence of these materials represents a final silencing of Ruth’s story, extending the original injustice into our own time.

What remains are fragments.

Elellanena’s coldblooded letters to her sister, sparse entries in household accounts, baptismal records that document a fiction, the recollections of descendants from neighboring plantations, and the disturbing silences where Ruth’s own voice should be.

From these fragments, we can reconstruct the outline of an atrocity, but never fully recover the experience of the woman at its center.

The Mayfield case forces us to confront an uncomfortable truth about historical memory that some injustices are so thoroughly constructed that they persist beyond the lives of the original victims and perpetrators.

The descendants of Ruth’s children live today without knowledge of their true lineage.

Their family history partially erased by a system designed to sever the maternal bond at its source.

This absence, this stolen ancestry represents the longest lasting impact of the Mayfield system.

Dr.

Richardson in her more recent work on intergenerational trauma in postslavery societies has suggested that such severed connections create ghost limb phenomena in family systems, unconscious sensations of absence that persist across generations without clear origin.

The descendants of Ruth’s children, she writes, may experience inexplicable feelings of loss or disconnection, emotional responses to a trauma they have no conscious knowledge of yet, which shapes their family story in profound ways.

The final chapter of Ruth’s story has yet to be written.

Perhaps someday advances in genetic genealogy will allow her descendants to discover their true lineage.

Perhaps some descendant of the Mayfield household will come forward with letters or journals that shed new light on Ruth’s fate.

Or perhaps her story will remain as it is now, partially illuminated with shadows that can never be fully dispelled.

What we do know with certainty is that in Charleston, South Carolina, between 1843 and 1853, a woman named Ruth endured a form of psychological torture designed specifically to deny her most fundamental human connection, that of mother to child.

She resisted through small acts of preservation and memory, maintaining maternal bonds in secret that she was forbidden to acknowledge in public.

And somewhere in America today, her descendants live on, carrying genetic heritage and perhaps unconscious memories of a woman whose name was nearly erased from history.

The quiet terror of Ruth’s story lies not in supernatural occurrences or graphic violence, but in the calculated human cruelty of the system that imprisoned her.

a system that understood that the most effective form of control targeted not just the body but the heart.

By attacking the maternal bond directly, the Mayfield arrangement struck at something so fundamental to human experience that its horror transcends time, speaking to us across the centuries as a warning about the depths of cruelty possible when one group of humans claims absolute ownership over another.

As we conclude this documentary reconstruction, we’re left with more questions than answers.

What became of Ruth after 1853? Did any of her children ever learn the truth? What happened to Mary, the 10th child who disappeared from the records? These questions may never be fully answered.

But by asking them, by refusing to accept the silence imposed by both the original perpetrators and subsequent efforts to suppress the full story, we perform a small act of resistance similar to Ruth’s collection of keepsakes.

We insist on remembering, however incompletely, a woman who was meant to be forgotten.

In Charleston today, tour guides lead visitors through the historic district, pointing out architectural features and relating sanitized stories of antibbellum society.

The Mayfield case rarely features in these narratives.

The subdivision built on the former plantation grounds bears no historical marker identifying what occurred there.

The silence continues, outlasting both Ruth and those who sought to erase her.

But in that small collection of objects, a button, a ribbon, a lock of hair, we glimpse a profound truth about the human capacity for resistance.

Even in the most dehumanizing circumstances, Ruth found ways to preserve her identity as a mother.

Each small treasure secreted away beneath the floorboards represented an insistence that the bonds slavery sought to destroy remained intact if hidden.

Through these tokens Ruth speaks to us across time.

I was here.

I was their mother.

I remembered even when they could not.

Perhaps the most fitting memorial to Ruth is not a stone marker or a historical plaque, but the act of telling her story, of refusing to accept the silence that was imposed upon her in life and has continued long after her death by speaking her name by acknowledging the specific cruelty she endured.

We counter the erasia that began in 1843 and has continued in various forms to the present day.

In the end, the most profound horror of the Mayfield case lies in its plausibility, in our recognition that such calculated psychological cruelty existed within a system that was defended as natural and just by those who benefited from it.

Ruth’s story forces us to confront not supernatural terror, but the very human capacity for designing systems of control that target the most fundamental human connections.

And in that recognition lies the true purpose of documenting such cases to ensure that the silence once imposed cannot become a permanent eraser.

News

✈️ U.S. F-15 FIRST STRIKE — ALLEGED CARTEL DRUG LAB ERASED IN SECONDS AS SKY ERUPTS IN A BLINDING FLASH ✈️ What officials described as a precision operation turned the night into daylight, with jets screaming overhead and a suspected production site reduced to smoking rubble in moments, sending a shockwave across the region and a message that the airspace above is no safe haven for hidden empires 👇

The Last Fortress: A Shocking Revelation In the heart of the Mexican jungle, Diego stood at the entrance of the…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: FBI & ICE SHATTER ALLEGED TRUCKING NETWORK WITH SOMALI TIES — 83 ARRESTED, $85M IN CASH AND WEAPONS STACKED AS EVIDENCE 🚨 Before sunrise, federal agents swept through depots and dispatch offices, hauling out duffel bags of currency and seizing firearms while stunned neighbors watched a logistics operation authorities claim was hiding a sprawling criminal enterprise behind everyday freight routes 👇

The Shadows of the Ghost Fleet In the heart of the Midwest, where the snow fell like a blanket over…

🚨 FBI & ICE STORM GEORGIA “CARTEL HIDEOUT” — GRENADE LAUNCHER DISCOVERED AND $900K IN DRUGS SEIZED IN A DAWN RAID THAT SHOCKED THE BLOCK 🚨 What neighbors thought was just another quiet morning exploded into flashing lights and tactical vests as agents swept the property, hauling out weapons and evidence while officials described a months-long investigation that culminated in a swift, coordinated takedown 👇

The Unraveling of Shadows: A Tale of Betrayal and Redemption In the heart of Jackson County, Georgia, the air was…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: DEA & FBI CRUSH ALLEGED CARTEL TRUCKING EMPIRE — HIDDEN ROUTES MAPPED, DRIVERS DETAINED, AND MILLIONS STACKED AS EVIDENCE 🚨 Before sunrise, highways turned into a grid of flashing lights as agents intercepted rigs, cracked open trailers, and traced coded dispatch logs, revealing what officials describe as a logistics web hiding in plain sight behind ordinary freight lanes 👇

The Fall of Shadows: A Cartel’s Empire Exposed In the dimly lit corridors of power, where shadows danced with deceit,…

🚢 U.S. NAVY TRAPS SINALOA CARTEL’S ALLEGED $473 MILLION “DRUG ARMADA” AT SEA — AND THE HIGH-STAKES STANDOFF UNFOLDS UNDER FLOODLIGHTS AND ROTOR WASH 🚢 Radar screens lit up, cutters boxed in fast boats, and boarding teams moved with clockwork precision as authorities described a sweeping maritime interdiction that turned open water into a chessboard, stacking seized cargo on deck while prosecutors hinted the ripples would travel far beyond the horizon 👇

The Abyss of Deceit: A Naval Reckoning In the heart of the Caribbean, where the turquoise waters glimmered under the…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: DEA & FBI DESCEND ON MASSIVE TEXAS LOGISTICS HUB — 52 TONS OF METH SEIZED AS 20 POLITICIANS ALLEGEDLY TIED TO A SHADOW NETWORK ARE THRUST INTO THE SPOTLIGHT 🚨 What began as a quiet federal probe detonated into a sweeping raid of warehouses and boardrooms, with agents hauling out towering stacks of evidence while stunned insiders whisper that the real shockwave isn’t just the drugs — it’s the powerful names now facing intense scrutiny 👇

Shadows of the Underground: The Texas Cartel Unveiled In the heart of Texas, where the sun sets over sprawling landscapes,…

End of content

No more pages to load