The restorers enlarged this portrait — what they found in the slave child’s hands shocked them

The restoers enlarged this portrait.

What they found in the slave child’s hands shocked them.

The conservation lab on the third floor of the National Museum of American History sat in near silence, broken only by the soft hum of specialized lighting equipment and the occasional click of a camera shutter.

David Martinez had worked as a photographic conservator for 12 years, but he still felt a flutter of anticipation each time he began restoring a piece of history that had been locked away in darkness for generations.

Today’s subject was a dgeray from 1858 donated by the estate of Louisiana family.

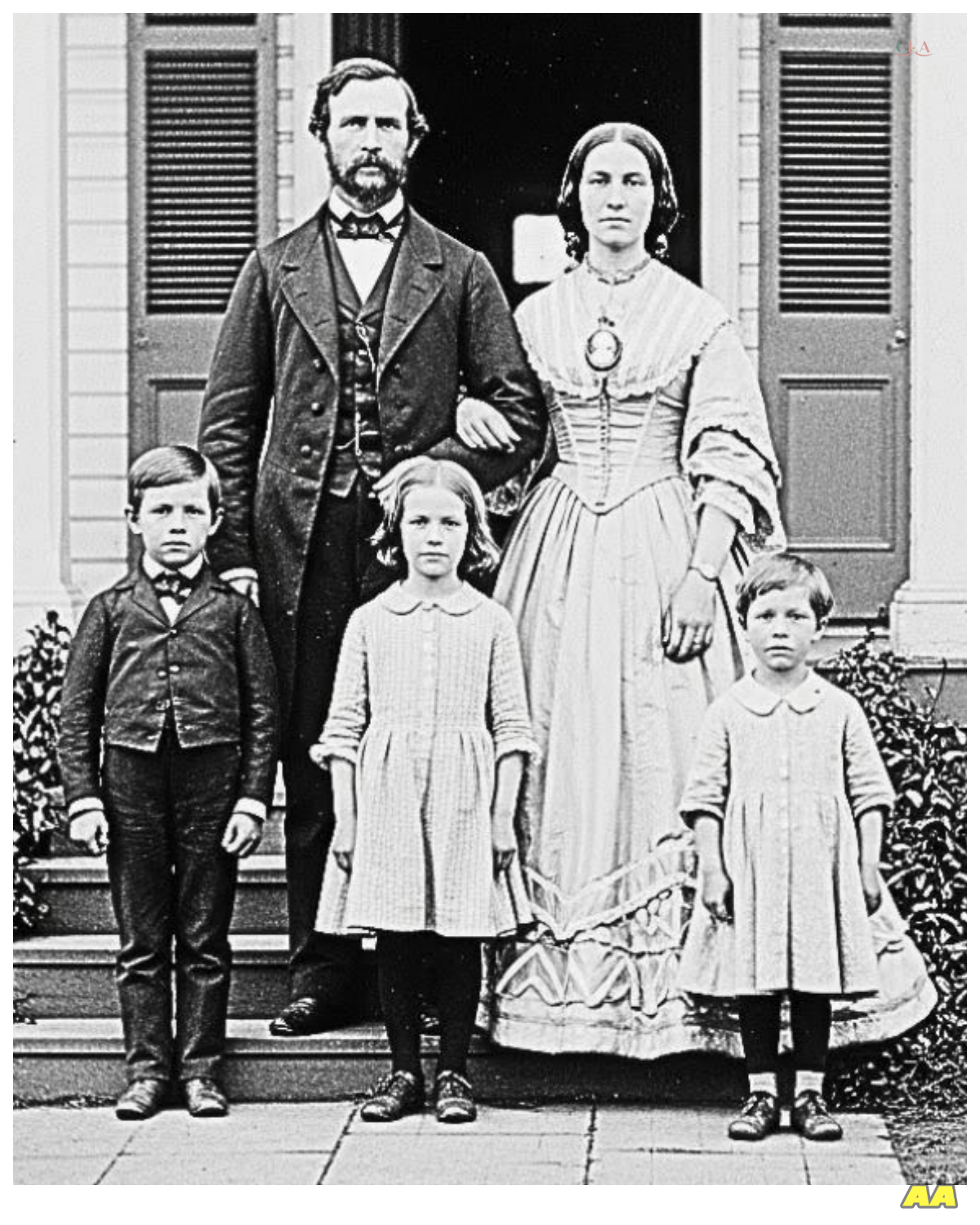

The image showed a well-dressed white family posed formally on the steps of what appeared to be a plantation house.

A man in a dark suit, a woman in an elaborate dress with a cameo brooch, and three children arranged in descending height order, standard for the era, unremarkable except for its age and fragile condition.

David adjusted his magnification glasses and carefully positioned the plate under the digital scanner.

The technology could capture details invisible to the naked eye, preserving every microscopic element before the silver began its inevitable decay.

As the highresolution scan progressed line by line across the image, his assistant Marcus stood behind him documenting the process.

Then something caught his eye.

In the bottom right corner of the frame, partially obscured by the shadow of the porch column, was another figure, a child, much smaller than the others, wearing a plain dress that blended into the darkness.

“Wait,” David said softly, his hand moving to pause the scan.

Do you see that? Marcus squinted at the screen.

I see a child standing apart from the family.

Not standing with them, standing behind them.

David’s stomach tightened with the familiar discomfort that came with confronting certain historical truths.

This child had been there when the photograph was taken, but positioned deliberately in the margins in the shadows.

He resumed the scan, adjusting the contrast and brightness settings.

As the resolution increased, more details emerged from the darkness.

The child’s face became clearer.

A girl perhaps seven or eight years old with large eyes staring directly at the camera.

Her hands were clasped in front of her holding something small.

“Can you enhance this section?” David asked, drawing a box around the child’s hands on the touchcreen.

The software isolated the area and magnified it further.

Both David and Marcus leaned forward simultaneously.

In the girl’s hands was a small wooden object, roughly rectangular, and carved into its surface, barely visible even at this magnification or marking, not random scratches, letters.

Are those words? Marcus whispered.

David’s hands trembled as he increased the magnification to its maximum level.

The letters came into focus, painstakingly carved with incredible precision.

Oh my god, David breathed.

Marcus, call Dr.

Patterson right now.

Doctor Patterson arrived within 20 minutes, his reading glasses perched on his graying hair and his tablet tucked under one arm.

As the museum’s chief historian specializing in antibbellum America, he had seen countless artifacts from the era of slavery.

But the urgency in David’s voice suggested something exceptional.

“Show me,” Dr.

Patterson said, pulling a chair beside David’s workstation, David navigated to the enhanced image of the child’s hands.

On the screen, magnified to reveal every carved line and shadow, the wooden object displayed its secret.

The letters were crude but deliberate, carved by someone with limited tools but unlimited determination.

Ruth, Dr.

Patterson read aloud, his voice barely above a whisper.

And below it, is that a date? 1851, Marcus confirmed, pointing to the numbers beneath the name.

7 years before this photograph was taken, Dr.

Dr.

Patterson removed his glasses and rubbed his eyes.

In his 30 years of historical research, he had studied countless documents about enslaved people, but the vast majority remained nameless in official records, reduced to age, gender, and monetary value.

To see a name literally carved and held by the child herself was unprecedented.

The object, Dr.

Patterson said, leaning closer.

Can we determine what it is? David adjusted the filters, bringing different layers into relief.

Based on the grain and the way light reflects, I believe it’s cypress wood, common in Louisiana.

The shape suggests it might have been part of something larger originally, cut down deliberately to be small enough to hide.

She’s holding it directly toward the camera, Marcus observed.

Not hiding it, but not displaying it obviously either, like she wanted it captured, but didn’t want to draw attention.

Dr.

Patterson stood and paced the small lab, his mind working through possibilities.

The family who donated this.

What do we know about them? David pulled up the accession file.

The estate belonged to descendants of Theodore Bowmont, who owned Bellere Plantation outside New Orleans.

The plantation house burned down in 1923, but the family maintained the land until the 1970s.

This dgera type was found in a safe deposit box.

Bowmont, Dr.

Patterson repeated.

He pulled out his tablet and began searching digitized historical records.

There should be plantation records, estate inventories.

If this girl was enslaved at Bellere, there might be documentation.

The three men worked in focused silence as afternoon light shifted through the lab windows.

Finally, Dr.

Patterson made a small sound of discovery.

here.

The state inventory from Belleref plantation dated January 1858.

It lists 47 enslaved individuals, but only eight are actually named.

He scrolled down.

Most are listed as fieldhand or houseworker with only age and gender.

But here, girlchild, house servant, age approximately eight, called Grace.

Grace, Marcus said, not Ruth.

Exactly.

Dr.

Patterson confirmed grimly.

If this child was called Grace by the Bumont family, but carved Ruth into this wood in 1851, then Ruth was her true name.

The Louisiana State Archives in Baton Rouge occupied a modern building, but its contents reached back through centuries of painful history.

David and Dr.

Patterson had driven down from Washington 2 days after the discovery, armed with copies of the enhanced photograph and a growing list of questions about Ruth’s life.

The reading room smelled of old paper and preservation chemicals, a research librarian named Janet guided them to a table and began bringing boxes of documents related to Belleref Plantation and the Bowmont family.

“We have quite extensive records,” Janet explained.

Theodore Bowmont was meticulous about documentation, plantation ledgers, correspondents, receipts, even some personal diaries, though I should warn you, much of it makes for difficult reading.

David nodded, pulling on white cotton gloves.

He had prepared himself for the bureaucratic language of slavery that reduced human beings to inventory items.

But somewhere in these pages might be the truth about Ruth.

Dr.

Patterson opened the first ledger dated 1850 to 1855.

The pages documented purchases, sales, births, and deaths.

Each enslaved person was listed with monetary value, skills, and condition.

Children under five were often listed with their mothers.

Children over five were listed separately.

Here, Dr.

Patterson said, finger tracing down a page dated March 1851.

Purchase record.

One negro woman approximately 22 years of age with infant daughter approximately 6 months, both in good health, purchased from the estate auction of Charles Dero, Ascension Parish.

Total price $800.

David leaned over to read the entry.

There were no names, just the cold transaction, but the date aligned perfectly.

March 1851.

If the infant was Ruth, this would have been when she arrived at Bellere with her mother.

They were sold together, Marcus said quietly, having insisted on joining the research trip, at least initially.

Not permanently, Dr.

Patterson warned.

They all knew slavery’s cruelty included constant threat of family separation.

They continued through the ledgers, page by exhausting page.

In 1852, a notation of a woman age approximately 23 assigned to house duties.

In 1853, a record of a child age approximately two helping in the kitchen.

The entries were maddeningly vague.

Then David found something that made his breath catch.

A different type of entry written in Theodore Bowmont’s own hand rather than an accountant’s neat script.

Punishment record.

David read aloud, voice tight.

Female house servant approximately 25 years of age.

Discovered teaching child to read using Bible verses.

10 lashes administered.

Child’s materials confiscated and burned, both confined to quarters for 3 days.

The room grew colder.

Teaching enslaved people to read was illegal in Louisiana.

The penalty could be severe.

But a mother had risked brutal punishment to give her daughter literacy, the key to preserving her own name.

She was teaching Ruth to read.

Marcus said that’s how Ruth knew what letters to carve.

Her mother taught her, knowing what would happen if caught.

David photographed the punishment record carefully, ensuring every detail was captured.

This was evidence of resistance, of love, defying the system designed to erase both.

The second day at the archives began with heavy clouds threatening rain.

Today, they would search sales records and death records from Bellere Plantation, looking for what happened to Ruth’s mother between 1854 and 1858.

Janet brought different boxes containing correspondence and bills of sale.

These are organized chronologically, she explained.

1855 to 1860.

If there was a sale during that period, it should be here.

2 hours into their search, Marcus found it.

His hands froze on the document.

voice cracking when he spoke.

Dr.

Patterson.

David, I found her.

The paper was a bill of sale dated October 1855.

David read it aloud, forcing himself to speak each word despite the anger building in his chest.

Bill of sale.

One negro woman, approximately 26 years of age, experienced in house service and cooking in good health and of soundbody.

Sold by Theodore Bowmont of Belleref Plantation, St.

James Parish to William Thornton of Thornton Cotton Works, Adams County, Mississippi.

Price received $950.

This 15th day of October 1855, silence filled the room except for the soft hum of climate control, Mississippi.

Ruth’s mother had been sold over 150 miles away.

In the 1850s, that distance might as well have been the other side of the world.

No letters, no visits, no way to ever see each other again.

Ruth would have been about 4 years old, Dr.

Patterson said quietly.

Old enough to remember, old enough to understand she was losing her mother.

Marcus was already searching his tablet.

Thornton Cotton Works was a large operation, over 200 enslaved workers by 1860.

The conditions were reported to be brutal, even by standards of the time.

William Thornton was known for working people to death and simply buying more.

David felt sick.

He looked at the photograph on his laptop screen, a little Ruth holding her wooden token.

She had been four when her mother was torn away.

But she had kept that piece of wood, kept her real name for at least four more years until the Dgeray type was taken.

How many nights had she held it, trying to remember her mother’s face, her voice, her touch? We need to find out if Ruth’s mother survived, David said firmly.

We need to know if she ever tried to find her daughter.

Dr.

Patterson nodded, expression grim.

Mississippi records from that era are less complete than Louisiana’s.

Many were destroyed during the Civil War, but we’ll try.

They spent the rest of the day documenting everything about the sale and about Bellere in the years following.

In the 1856 inventory, Ruth appeared again, now listed as girlchild, called Grace, approximately 5 years, house servant.

She was alone.

Her mother’s name existed nowhere in official records, only in the wooden token clutched in small hands.

As they prepared to leave, Janet approached with another box.

I was listening to what you’ve been researching.

I pulled personal correspondence from the Bumont family, 1855 to 1858.

Sometimes letters mention the household in ways official records don’t.

The third morning dawned clear and humid, the storm having passed overnight.

David arrived early, eager to examine the Bowmont family correspondents.

These personal letters might contain details that never made it into official records.

the human moments, the casual mentions that revealed so much about daily life.

Doctor Patterson joined him, and together they began carefully removing letters from their protective sleeves.

The correspondence was mostly between Theodore Bowmont and his business associates, discussions of cotton prices and trade routes, but occasionally there were letters to and from his wife Elizabeth, who had relatives in Charleston.

Marcus arrived with coffee and began helping them sort through the documents chronologically.

We’re looking for anything from late 1855 onward.

Doctor Patterson said right after Ruth’s mother was sold.

An hour into their work, David found a letter from Elizabeth Bowmont to her sister, dated November 1855, just weeks after the sale.

He read it silently first, his jaw tightening, then read it aloud.

Dear Catherine, I write to you with troubled heart.

Theodore has sold Mary, our cook, to a cotton operation in Mississippi.

The money was good, he says, and we needed to balance the accounts after the poor harvest.

But the child Mary left behind has been inconsolable.

She refuses to eat, will not speak, and clutches some wooden trinket day and night.

I fear we may lose her to grief.

Theodore says she will adjust, that children are resilient, but I confess the sight of her haunts me.

She stands in shadows now, silent as a ghost.

I wonder if we have committed a great sin, sister, though Theodore assures me it is simply the way of our world.

The lab fell silent.

David’s hands shook as he held the letter.

This was Ruth.

This was the little girl in the photograph, grieving her mother, holding her wooden token with her name carved into it.

Mary, Marcus said softly.

That was her mother’s name.

Dr.

Patterson was already making notes.

Mary, approximately 26 years old in 1855, sold to Thornon Cottonworks in Adams County, Mississippi.

That gives us something to search for.

If she survived, if she left any records after the Civil War, we might be able to trace her.

David carefully photographed the letter, ensuring Elizabeth Bowmont’s words were preserved.

The woman’s guilt was evident in her writing, but not enough to change what had been done.

She had witnessed a child’s heartbreak and done nothing to stop it.

Keep looking.

Dr.

Patterson said there might be more.

They found two more letters mentioning Ruth over the next hour.

One from Theodore Bowmont to a business associate in March 1856 mentioning that the child called Grace has finally resumed her duties, though she remains peculiarly quiet and attached to some piece of wood she will not surrender.

Another from Elizabeth in July 1857, noting that Grace has grown into a useful servant, though she possesses an odd intensity in her eyes that sometimes unnerves the other house staff.

She never let go of it, Marcus said, looking at the Dgeray type.

For years, she held on to her name, held on to her mother.

David studied the photograph again with new understanding.

Ruth’s silence, her intensity, her positioning in the shadows, all of it made sense now.

She was grieving, resisting, remembering.

The wooden token was her act of defiance in a world that wanted to erase her.

The research took on new urgency as David, Dr.

Patterson, and Marcus expanded their search to Mississippi records.

They needed to find what happened to Mary, Ruth’s mother, and whether she survived the brutal conditions at Thornton Cotton Works long enough to see freedom.

Dr.

Patterson made contact with historians at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

Within days, they received scanned documents from Thornton Cottonworks, though the records were frustratingly incomplete.

Many had been destroyed when Union troops burned the plantation in 1863.

What survived told a grim story, Thornton’s operation had been massive and ruthless.

The mortality rate among enslaved workers was appalling.

Nearly 15% per year died from overwork, disease, and malnutrition.

William Thornton’s philosophy had been simple and monstrous.

Work people until they died, then buy more.

But buried in the surviving records, David found her.

An inventory from 1860 listed, “Mary, negro woman, approximately 31 years, field hand, fair health.

” She had survived 5 years.

Five years of brutal labor in the cotton fields of Mississippi.

Torn from her daughter, stripped of her position as a cook and forced into the killing work of the fields.

She was alive in 1860, David said, his voice thick with emotion.

She survived.

The Civil War began in April 1861.

Dr.

Patterson noted.

Mississippi was one of the first states to secede.

Thornton Cotton Works would have been right in the path of Union advancement up the Mississippi River.

Marcus pulled up military records on his laptop.

Union forces took Nachez in 1863.

Adams County was occupied.

The Emancipation Proclamation had already been issued.

If Mary was still alive when Union troops arrived, she would have been freed.

The question was whether Mary had survived until 1863.

The gap between the 1860 inventory and the Union occupation was 3 years.

3 years of war, chaos, and even harsher conditions as the Confederacy demanded more production from plantations to support their military.

Janet had given them one more resource, Freedman’s Bureau records.

After the Civil War, the Bureau had been established to help formerly enslaved people transition to freedom.

They kept records of labor contracts, family reunification requests, marriages, and land claims.

Doctor Patterson accessed the digitized Freedman’s Bureau records for Adams County, Mississippi.

Searching for anyone named Mary, who matched the right age and description.

The database was enormous and poorly indexed.

Days of searching turned up dozens of Marys, but none they could definitively connect to Ruth’s mother.

Then Marcus found something different.

Not in the Freedman’s Bureau records, but in a collection of letters held by the Adams County Historical Society.

A letter dated July 1865, written by a formerly enslaved woman named Mary to the Freriedman’s Bureau office in Nachez.

The handwriting was crude but legible.

The words misspelled but clear in their desperate purpose.

Marcus read it aloud, his voice breaking.

To who it may concern, “My name is Mary.

I was slave at Thornon Place until free come.

I’m looking for my daughter.

She was took from me in 1855, sold to Bowmont Plantation in Louisiana.

Her name is Ruth.

She would be about 14 years now.

I’ve been told you help people find they family.

Please, if you know anything about Ruth or Bowmont Plantation, write to me.

Care of Thornon Place.

I can read some and write some.

A teacher here helped me write this.

I will never stop looking for my daughter, Mary.

David had to step away from the table, his emotions overwhelming him.

Mary had survived.

She had survived 5 years of slavery at Thornton Cottonworks, survived the Civil War, and the moment she was free, the first thing she did was try to find her daughter.

The discovery of Mary’s letter transformed their research.

They now knew Mary had survived until at least July 1865 and was actively searching for Ruth.

The question became whether she had ever found her daughter and what had happened to Ruth during and after the Civil War.

David and his team returned to Louisiana records, this time focusing on the Civil War years and reconstruction.

Bellariv plantation records from 1861 to 1865 were sparse.

Theodore Bowmont had apparently been less diligent about documentation as the war disrupted normal plantation operations.

But they found evidence that Bellere had continued operating throughout the war, producing cotton for the Confederacy until Union forces occupied southern Louisiana in 1863.

After that, the plantation system collapsed.

Enslaved people were declared free, though freedom came with its own desperate challenges.

In the Freedman’s Bureau records for Louisiana, they searched for Ruth.

The records included thousands of names.

formerly enslaved people registering labor contracts, seeking family members, claiming new identities with full names for the first time, and then David found her.

A registration form dated September 1865 filled out at the Freriedman’s Bureau office in New Orleans.

The handwriting was careful and clear.

Name: Ruth Mary.

Age approximately 14 years.

Former place of enslavement, Bellere Plantation, St.

James Parish.

Currently residing, New Orleans, working as house servant for the Bumont family under labor contract.

seeking information about Mary, mother, last known location.

Thornton CottonWorks, Adams County, Mississippi.

Sold away October 1855.

Ruth Mary, Dr.

Patterson said softly.

She took her mother’s name.

She remembered.

The form indicated Ruth was still working for the Bumont family, now under a labor contract that technically made her free, but practically kept her in a similar position.

Many formerly enslaved people had few options in the immediate aftermath of the war, and ended up working for their former enslavers under exploitative contracts.

But Ruth had registered with the Freriedman’s Bureau.

She had given her true name, and she was looking for her mother.

“They were both searching for each other,” Marcus said, comparing the dates.

Mary wrote her letter in July 1865.

Ruth filed this form in September 1865, just two months apart, both trying to find each other through the Freedman’s Bureau.

Did they succeed? David wondered aloud.

“Did the bureau connect them?” The Freedman’s Bureau had been overwhelmed with family reunification requests.

Thousands of families had been torn apart by slavery, and now everyone was searching, hoping, grieving.

The bureau did its best, but resources were limited, and the South remained chaotic and dangerous during reconstruction.

Dr.

Patterson began searching for correspondence between the Mississippi and Louisiana Freedman’s Bureau offices.

If Mary’s request and Ruth’s request had been matched, there should be some record of communication.

Days of searching yielded nothing.

No letters, no reunion records, no indication the two requests had ever been connected by the overwhelmed bureau system.

The silence in the archives was heartbreaking.

Two women searching desperately for each other, their requests filed in different states, possibly never cross referenced in the chaos of reconstruction.

But then Janet, who had been following their research with growing investment, suggested another avenue, church records, she said.

After the war, African-American churches became centers of community organization.

They kept their own records, marriages, baptisms, deaths, and they helped families reunite.

If either Mary or Ruth connected with a church, there might be records.

It was a long shot, but they had come too far to give up.

Now, finding the right church records proved to be another monumental task.

African-American churches had sprouted across the South during reconstruction.

Many keeping meticulous records as their communities rebuilt.

But 70 years and more had passed, and many records had been lost to time, fire, and deliberate destruction during later periods of racial violence.

Dr.

Patterson contacted colleagues at Tulain University and Dillard University in New Orleans, both of which had extensive collections of African-American historical records.

Meanwhile, David reached out to the Mississippi Department of Archives and History to search church records in Adams County.

The breakthrough came from an unexpected source.

A historian at Dillard named Dr.

Ela Foster had been working on a project documenting African-American families during reconstruction.

When Dr.

Patterson explained what they were looking for, she immediately thought of one specific collection.

There’s a diary Dr.

Foster told them over a video call, her eyes bright with excitement kept by Reverend Samuel Cooper of Mother Bethl AM Church in New Orleans.

He was incredibly detailed about his congregation during the years 1865 to 1870.

He documented reunions, marriages, deaths, everything.

If Ruth connected with his church, she might be in there.

2 days later, David was sitting in a reading room at Dillard University.

White gloves on, carefully turning the pages of Reverend Cooper’s diary.

The entries were dense, written in fading ink, chronicling the struggles and triumphs of a community emerging from bondage.

He worked through 1865, page by page, month by month, October, November, December.

nothing about Ruth.

He moved into 1866, forcing himself to read carefully despite his impatience.

And then, in an entry dated March 17th, 1866, he found it.

Today, I witnessed the Lord’s greatest mercy.

Reverend Cooper had written, “A mother and daughter, separated by the wickedness of slavery for more than 10 years, were reunited in our church.

Mary, who traveled all the way from Mississippi on foot and by wagon, and her daughter, Ruth, who never ceased keeping her mother’s memory alive.

The girl carried with her a piece of wood with her name carved upon it, carved by her mother’s hand when she was but an infant.

Both wept openly as did many in the congregation.

I baptized them together as they wished to begin their lives in freedom with God’s blessing.

They have taken the family name Freeman as Ruth said she wished to be free in name as well as spirit.

David couldn’t breathe.

His vision blurred with tears.

They had found each other.

After 10 years of separation, after slavery, after war, after desperate searching, through the chaos of reconstruction, Mary and Ruth had found each other.

He immediately called Dr.

Ter Patterson and Marcus, reading them the entry over the phone.

Both men’s voices cracked with emotion as they absorbed the meaning of what had been found.

Ruth Freeman, Marcus said.

She chose that name.

Ruth Mary Freeman.

They found each other.

Dr.

Patterson repeated as if he couldn’t quite believe it.

Against all odds, they actually found each other.

But the discovery raised new questions.

What happened after the reunion? How did Mary find Ruth? How long did they have together? David returned to Reverend Cooper’s diary, searching for more entries about the Freeman family.

Over the following months, there were several more mentions.

Mary and Ruth were active in the church community.

Ruth, the diary noted, was teaching younger children to read, continuing the work her mother had begun when she was small.

Mary worked as a laress and was known for her generosity to others in need despite having little herself.

Following the thread of Mary and Ruth Freeman through reconstruction required piecing together fragments from multiple sources, church records, census data, city directories, and land records.

Each document added another brushstroke to the portrait of their lives after reuniting.

The 1870 census provided the next solid evidence.

David found them listed in New Orleans.

Ward 5.

Mary Freeman, Negro, female, age 41, larress.

Ruth Freeman, negro, female, age 19, teacher.

Living in the same household, working, building a life together in freedom.

Ruth became a teacher, Marcus said with pride, as if she were someone he had known personally.

She went from being taught in secret, being punished for learning, to teaching others.

Dr.

Patterson had found even more.

In records from the Freriedman’s Bureau school system, Ruth appeared as one of the teachers at a school established in 1869 for African-American children.

The school operated out of Mother Bethl amme church, the same church where she and her mother had been reunited.

A newspaper article from the New Orleans Tribune, an African-American newspaper from 1870, mentioned the school and its teachers, including Miss Ruth Freeman, who herself learned to read under the most harrowing circumstances, and now dedicates herself to ensuring the next generation will never be denied the gift of literacy.

David spent days searching for more, and the picture that emerged was one of resilience, determination, and purpose.

Mary and Ruth had not just survived, they had built a life that mattered.

They had joined a community, contributed to it, and helped others rise from the ashes of slavery.

But then the trail went cold.

After 1870, references to Mary Freeman disappeared from the records.

No death certificate could be found, no burial record, nothing in the church registers.

She might have died, Dr.

Patterson said.

J recordkeeping for African-Americans in the 1870s was still inconsistent, especially for ordinary people.

Deaths went unregistered all the time.

Ruth’s trail continued a bit longer.

In 1872, a marriage record showed Ruth Mary Freeman married to James Wilson.

both of New Orleans.

Ceremony performed by Reverend Samuel Cooper.

In the 1880 census, Ruth appeared as Ruth Wilson, Negro, female, age 29, keeping house.

Living with James Wilson, a carpenter, and two children, Samuel, age 6, and Mary, age four.

She named her daughter Mary, Marcus said softly, after her mother.

The last record they found was in a city directory from 1883, listing Wilson, James Carpenter, and Ruth, teacher, residing at 247 Burgundy Street.

After that, nothing.

The trail simply ended.

David sat back feeling both satisfied and frustrated.

They had found so much, the separation, the suffering, the miraculous reunion, the life built afterward.

But the ending remained uncertain, fading into the anonymity that claimed so many lives from that era.

We’ve done what we set out to do.

Dr.

Patterson said, “We’ve told Ruth’s story.

We’ve given her back her name and her mother’s name.

We’ve shown that they survived, that they found each other, that they lived lives of meaning and dignity.

But David wasn’t quite ready to stop.

There was one more place to look.

David’s final idea came from thinking about Ruth’s children.

If Ruth had named her daughter Mary after her mother, and if that daughter had survived to adulthood, there might be descendants, people alive today who carried Ruth’s blood, who might have family stories passed down through generations.

Working with Dr.

Foster at Dillard University, they began tracing forward from Ruth’s children listed in the 1880 census, Samuel and Mary Wilson.

The search was complicated by common names and incomplete records.

But genealological databases and DNA ancestry services had made such searches more possible than ever before.

After two weeks of research, Dr.

Foster found a promising lead.

A genealogy post from 2019 by someone named Patricia Wilson Johnson researching her family history.

She had traced her line back to a Ruth Wilson teacher who had lived in New Orleans in the 1880s and was trying to find out more about Ruth’s origins.

David immediately reached out through the genealogy website.

3 days later, his phone rang.

The woman on the other end of the line introduced herself as Patricia, calling from Atlanta.

She was 73 years old, a retired school teacher herself.

“And yes, Ruth Wilson was her great great-grandmother.

We always knew she had been enslaved,” Patricia said, her voice strong and clear.

“That story was passed down.

” “And there was always a family story about a piece of wood with a name carved into it, though the actual object was lost generations ago.

” “My grandmother said Ruth kept it her whole life, that it had been carved by Ruth’s mother when Ruth was a baby.

” David’s heart raced.

“Miss Johnson, I have something to show you.

Can we set up a video call? The next day, David, Dr.

Patterson, Marcus, and Dr.

Foster gathered in the museum’s video conference room.

On the screen, Patricia appeared.

Her grown children gathered around her.

David shared his screen and slowly navigated to the enhanced dgerpype, zooming in to show Ruth standing in the shadows, her hands clasped around the wooden token.

Patricia gasped, her hand going to her mouth.

Her children leaned forward, staring at their ancestors face captured across 166 years.

“That’s her,” Patricia whispered.

“That’s Ruth.

That’s my great great grandmother.

David zoomed in further, showing the carved letters.

Ruth, 1851.

Your family’s story is true, David said gently.

And there’s more.

We found records of Ruth’s mother, Mary.

They were separated when Ruth was 4 years old, sold to different places, but they found each other again in 1866 after the war.

They were reunited.

Tears streamed down Patricia’s face as David walked her through everything they had discovered.

the sale, the punishment for teaching Ruth to read, Mary’s survival, her letter to the Freriedman’s Bureau, Ruth’s registration, and finally, Reverend Cooper’s diary entry about their reunion in Mother Bethl amme church.

“They found each other,” Patricia said, her voice breaking.

“All these years, I wondered if Ruth ever saw her mother again.

My grandmother always said she hoped so, but we never knew.

” Patricia shared her own family stories.

Ruth had lived until 1891, dying at age 40 from pneumonia.

She had taught until the end, even while raising four children.

Her daughter Mary had become a teacher as well.

And then Mary’s daughter, Patricia’s grandmother, had also taught school.

Four generations of teachers, Patricia said with pride.

All because Ruth’s mother risked everything to teach her to read.

And Ruth never forgot that gift.

The museum quickly arranged for Patricia and her family to visit Washington.

A month later, David stood beside them in a special exhibition the museum had created.

The Dgeray type was displayed prominently with Ruth’s image enlarged alongside it.

Text panels told her story.

The separation, the survival, the reunion, the legacy.

The wooden token itself had never been found, likely lost or discarded long ago by people who never understood its significance.

But the museum’s conservation department had created a replica based on the photograph, showing visitors what Ruth had held on to through years of suffering.

Patricia stood before the image of her ancestor.

Her family gathered around her.

Her youngest grandchild, a girl of seven, looked up at the photograph with wide eyes.

“Is that really our grandma from a long time ago?” the child asked.

Yes, Patricia said, kneeling beside her.

That’s Ruth.

She was brave and strong, and she never forgot who she was, even when people tried to make her forget.

And because she remembered, we know who we are.

David watched the family together, feeling the weight of what they had accomplished.

Ruth’s story had been hidden for 166 years, visible only as a shadow in a photograph.

But through careful research, determination, and the power of modern technology, that shadow had been brought into the light.

The little girl reached out as if to touch the photograph, her finger stopping just short of the glass.

I want to be a teacher, too, she said, like Grandma Ruth.

Patricia smiled through tears and embraced her granddaughter.

Around them, other museum visitors stopped to read Ruth’s story, to see her face, to understand what she had endured and how she had triumphed.

Ruth’s name, carved so carefully into wood by a mother who loved her, had survived after all.

Not just survived, it had echoed across generations.

A testament to love that even slavery could not destroy.

And to the human need to remember, to be remembered, and to never let our truths be erased.

David stepped back, letting the family have their moment.

Beside him, Dr.

Patterson spoke quietly.

This is why we do this work.

This is why it matters.

On the wall, Ruth stared out from 1858, her small hands holding her identity, her truth, her mother’s love.

And now finally everyone could see

News

Look Closer: The Mirror in This 1907 Studio Photo Holds a Terrifying Truth [Music] The Maryland Historical Society’s photography archive smelled of old paper and preservation chemicals. Thomas Rivera had spent 15 years cataloging Baltimore’s photographic history, handling thousands of glass plates and faded prints that documented the city’s past. The Thornon Studio collection had arrived. Three weeks ago, three boxes of immaculately preserved photographs from one of Baltimore’s premier portrait studios, operating from 1895 to 1920. Thomas has been working through them methodically, recording details about each image, subjects, dates, locations, technical notes. He removed another large format photograph from its protective sleeve, a formal family portrait, typical of the era. The lighting was professional, the composition carefully arranged. The photograph showed four people posed in an elegant studio setting. Heavy velvet drapes framed the scene. An ornate Barack mirror with an elaborate gilded frame hung prominently on the back wall, positioned slightly to the left at an unusual angle. At the center stood a tall, distinguished man in his 40s, wearing a dark suit, his expression stern and authoritative.

Look Closer: The Mirror in This 1907 Studio Photo Holds a Terrifying Truth [Music] The Maryland Historical Society’s photography archive…

In 1904, This Family Took a Picture. Decades Later, They Find Something Sinister In 1904, this family took a picture. Decades later, they find something sinister. In November 1978, Sarah Henderson entered her deceased grandmother’s study in the family’s Lincoln Park mansion. The Victorian home had belonged to the Henderson family for over 70 years, and Elellanena Henderson had been its meticulous keeper of memories and documents. The study contained decades of accumulated family history. Sarah worked methodically through each drawer of the mahogany desk, preserving what she could of her family’s past. When she opened the bottom drawer, her hands found a leather-bound photograph album hidden beneath financial papers. The album’s brass clasp had tarnished with age, and its leather binding showed the wear of many decades. Inside, sepia toned photographs documented Chicago’s high society from the early 1900s. Page after page revealed formal portraits, social gatherings, and family celebrations from a bygone era. One photograph stood out among the collection.

In 1904, This Family Took a Picture. Decades Later, They Find Something Sinister In 1904, this family took a picture….

🌊 MH370 Wreckage Finally Recovered After a Decade Lost—History’s Biggest Aviation Mystery Solved in Stunning Underwater Discovery That Will Shock the World 😱 In a heart‑pounding, dramatic narrator tone, the lead teases deep-sea sonar revealing twisted metal, personal effects preserved in silt, and decades of speculation finally colliding with reality, as experts and families confront answers they never thought they’d hear 👇

The Shadows of the Ocean In the early hours of March 8, 2014, the world was unaware that history was…

End of content

No more pages to load