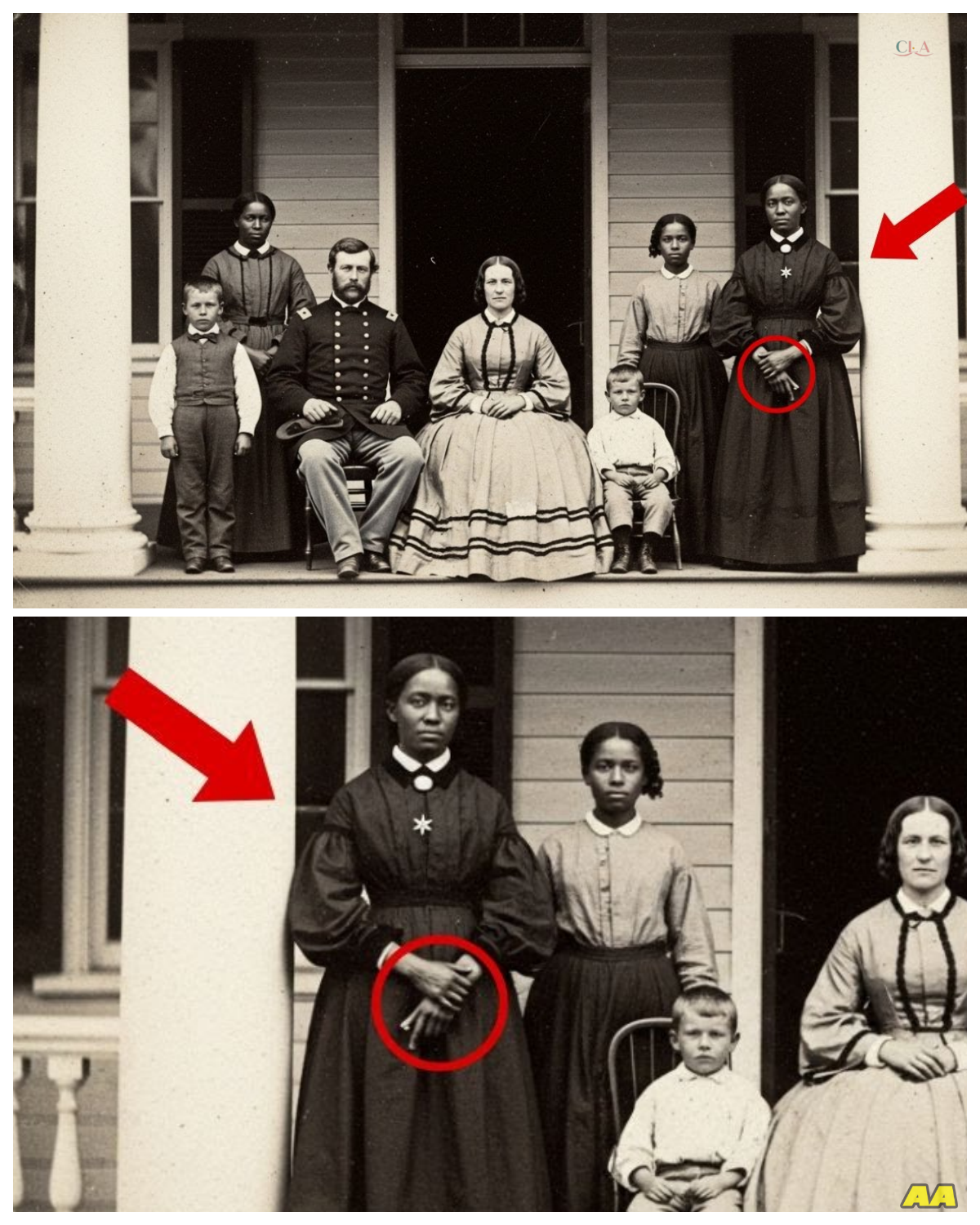

The restorers enlarged this portrait and discovered something in the slave that no one had noticed

The conservation lab at the Charleston Heritage Museum smelled of chemicals and old paper.

Sarah Williams adjusted her magnifying lamp over the dgeray type, her gloved hands steady as she positioned the 1862 photograph under the scanner.

It was her third week cataloging items from the Whitfield estate collection, and most pieces had been unremarkable, faded family portraits, property deeds, ledgers documenting cotton yields.

This particular photograph showed the Whitfield family posed on their plantation verand.

James Whitfield stood rigid in his Confederate officer’s uniform.

His wife, Catherine, seated beside him in an elaborate hoop skirt.

There are three children arranged around them like porcelain dolls.

The image quality was exceptional for the era, crisp and wellpreserved despite its age.

Sarah had processed dozens of similar portraits.

Wealthy southern families documenting their prosperity, their status, their version of history.

She began the high resolution scan, watching the progress bar creep across her screen.

The museum’s digitization project aimed to make the collection accessible to researchers and descendants seeking their family histories.

As the scan completed, Sarah zoomed in to check the image quality, examining the faces first, then the clothing details, the architectural elements of the veranda.

Her cursor drifted toward the background, where the plantation houses columns created deep shadows.

She paused.

There, barely visible in the darkness behind the family stood several figures.

The enslaved household staff, she realized, included in the frame, but pushed to the margins, their faces deliberately obscured by shadow and distance.

Sarah leaned closer to her monitor, increasing the magnification further.

One woman stood slightly apart from the others, her face partially visible.

And then Sarah saw it, her breath caught.

The woman’s hands folded at her waist weren’t simply resting.

They were positioned in a deliberate configuration, fingers interlaced in a pattern that seemed purposeful, intentional.

Sarah’s pulse quickened.

She had seen something similar before in her research on underground railroad communication methods.

But she needed to be certain.

Sarah spent the next two hours cross-referencing historical databases on her second monitor.

She pulled up academic papers on coded communication among enslaved people, studies of quilting patterns used as root maps, documentation of hand signals employed by conductors on the Underground Railroad.

The position of the woman’s hands matched descriptions she found in a 1932 oral history interview with a freedom seeker named Jacob Harris, who had escaped from South Carolina in 1863.

The signal meant safe house or friend, a message that could be captured in photographs hidden in plain sight.

While slave owners remained oblivious, Sarah printed several reference images and returned to the dgeraype, comparing them carefully.

The match was undeniable.

This woman had deliberately posed with her hands positioned to communicate something to those who understood the language.

Sarah’s colleague, Marcus Chen, an archivist specializing in African-American history, stopped by her workstation.

“Still on the Whitfield collection?” he asked, setting down his coffee.

Sarah turned her monitor toward him without a word.

Marcus leaned in, studying the image.

His expression shifted from casual interest to focused attention.

“Is that what I think it is?” he asked quietly.

“I think so,” Sarah replied.

“But there’s more.

” She zoomed in further on the woman’s dress, pointing to the collar.

Barely visible against the dark fabric was a small pin no larger than a button.

The enhanced resolution revealed intricate detail, tiny symbols etched into the metal surface, including what appeared to be a star.

The North Star, Marcus whispered, the symbol of the Underground Railroad.

They sat in silence for a moment, the implications settling over them.

This wasn’t just a family portrait.

It was evidence of resistance, of courage, of a woman who had risked everything to leave a message that would survive more than 160 years.

We need to find out who she was, Sarah said.

Marcus nodded.

The Whitfield estate records should have household inventories.

They listed enslaved people by name, age, assigned duties.

The thought made Sarah’s stomach turn, but she knew those dehumanizing documents might be their only path to identifying the woman in the photograph.

Let’s start there, she agreed.

And I want to examine every inch of this image.

If she left one message, there might be others.

The Whitfield estate papers filled three archive boxes meticulously organized by the museum’s previous archavists.

Sarah and Marcus spread the documents across the large research table in the temperature-cont controlled vault.

Ledgers recorded cotton production, financial accounts, correspondence with factors in Charleston and Liverpool.

And then there were the inventory lists, dated and updated annually, listing human beings as property with the same clinical precision as livestock and furniture.

The 1862 inventory, compiled just months before the photograph was taken, listed 18 enslaved individuals on the main house grounds.

The document provided names, estimated ages, assigned roles, and assessed monetary values.

Sarah’s hands trembled slightly as she read through the list.

here,” Marcus said, pointing to an entry near the bottom.

“Eliza, age approximately 35, house servant seamstress, valued at $900.

” $900.

The reduction of a human life to a price tag.

Sarah photographed the page with her phone, then continued searching through the papers.

She found Eliza’s name mentioned in several other contexts.

A receipt for fabric purchased for household sewing, a note in Katherine Whitfield’s diary about alterations to a dress, a medical expense record from 1859 when Eliza had been treated for fever.

But nothing that revealed who Eliza truly was beyond her function in the household.

We need more than this, Sarah said, frustration creeping into her voice.

These records tell us nothing about her as a person.

Marcus was already searching on his laptop.

The Avery Research Center might have oral histories from this area.

And there’s the Freed Men’s Bureau records from after the war.

If Eliza survived until emancipation, she might have registered, applied for assistance, searched for separated family members.

Sarah returned to her computer and pulled up the Dgerayotype again, studying Eliza’s partially visible face with new intensity.

The woman had strong features, her gaze directed not at the camera, but slightly to the left, as if watching something beyond the frame.

Her expression was carefully neutral, the mask that enslaved people had to wear in the presence of their enslavers.

But knowing what Sarah now knew about the hand signal, she could see something else in that face.

Determination, perhaps even defiance.

She was part of the Underground Railroad, Sarah said aloud, the certainty growing stronger.

She had to be.

This wasn’t just a random gesture.

She knew exactly what she was doing.

Dr.

Patricia Johnson, director of the Avery Research Center for African-American History and Culture, welcomed Sarah and Marcus into her office the following morning.

The walls were lined with photographs, documents, and artifacts chronicling the African-American experience in the Low Country.

“Dr.

Johnson, a distinguished historian in her 70s, listened intently as Sarah explained their discovery.

” “The Whitfield Plantation,” Dr.

Johnson said thoughtfully, pulling a book from her shelf.

“Oh, I know that property.

It’s on a Disto Island, correct?” Sarah nodded.

The island had significant underground railroad activity, though it’s not widely documented.

Many people don’t realize how extensive the network was in South Carolina.

We tend to focus on northern routes, but there were active networks throughout the South, helping people escape to Union controlled areas to ports where they could board ships heading north or even to the Bahamas.

She opened the book to a marked page showing a handdrawn map of the Low Country with notations and faded ink.

This was created in 1935 by a historian who interviewed elderly former slaves.

They identified safe houses, meeting points, river crossings.

Look here, her finger traced a line on the map.

Edesto Island had at least three known safe houses operated by free black families and sympathetic whites, Quakers mostly.

The Whitfield Plantation is right in this corridor.

Sarah felt a chill run down her spine.

So Eliza could have been a conductor, helping people escape from the plantation itself.

Dr.

Johnson smiled.

It’s possible.

House servants had more mobility than field workers, more access to information.

They heard conversations, read letters left lying around, knew when slave catchers were in the area or when the master would be away.

A seamstress would have legitimate reasons to move between the main house and the slave quarters to visit other plantations for work.

Perfect to cover for underground railroad activities.

Marcus leaned forward.

Do you have any records of conductors operating in this area during the war years? Dr.

Johnson moved to her filing cabinet.

We have some oral histories, but names are often incomplete or changed.

People used code names, false identities.

After the war, many were afraid to speak openly about their involvement, fearing retribution even decades later.

But let me check our database.

She spent several minutes typing, scrolling through records.

Then she paused, reading something on her screen.

There’s a reference here in a 1938 WPA interview with a woman named Ruth, born enslaved on a Disto Island in 1857.

She mentions a woman called Aunt Eliza, who worked as a seamstress and would sing certain songs when it was safe to move.

The interviewer didn’t understand the significance, just recorded it as folklore.

Dr.

Johnson printed the WPA interview transcript, and Sarah read it with growing excitement.

Ruth’s testimony, recorded when she was 81 years old, painted a vivid picture of life on Edesto Island during the Civil War years.

The interviewer had been more interested in stories about plantation life and folk customs, but buried in the narrative were fragments of something more significant.

Aunt Eliza, she was a smart woman, Ruth told the interviewer.

She could sew anything, make a dress from scraps, fix any tear.

But she had another gift.

She knew things, heard things.

When the patty rollers were coming, she’d sing Wade in the water to when it was safe.

She’d hum follow the drinking gourd.

We all knew what it meant, but the white folks just thought she’d like to sing while she worked.

The transcript continued with Ruth describing how people would sometimes disappear from the plantation at night, and how Aunt Eliza always seemed to know when someone was planning to run.

She never said nothing directly, but she’d leave things.

A quilt hung a certain way, a candle in a window, a mark on a tree, signs for those who understood.

Sarah looked up at Dr.

Johnson.

This has to be the same Eliza.

The timeline matches the location, the work as a seamstress.

Dr.

Johnson nodded slowly.

It’s compelling evidence, but we need to find more concrete connections.

Ruth’s testimony gives us context, but we need to trace what happened to Eliza after this photograph was taken.

Did she survive the war? Was she emancipated? Did she leave any descendants who might have family stories? Marcus was already searching through Freriedman’s Bureau records on his laptop.

I’m looking at registration records from Charleston County between 1865 and 1868.

There are thousands of entries.

Let me filter by name and approximate age.

Minutes passed in tense silence as he scrolled through digitized documents.

Then he stopped.

I found something.

Eliza Freeman, registered in Charleston, April 1865.

Age listed as about 38, formerly enslaved on a dysto island.

Occupation listed as seamstress.

The room fell silent.

Freeman, the surname chosen by thousands of formerly enslaved people to mark their new status.

Sarah felt emotion welling up in her throat.

Eliza had survived.

She had lived to see freedom.

“Does the record show anything else?” she asked.

Marcus continued reading.

She registered two children with her, a daughter named Hannah, age 12, and a son named Isaac, age 8.

And there’s an address, or at least a general location, Radcliffe Street, near the waterfront.

Dr.

Johnson stood up, energized.

Radcliffe Street was in a neighborhood where many freed people settled after the war.

Some of those families are still in Charleston.

Their descendants might have stories, family bibles, photographs, documents.

Finding the descendants took three weeks of methodical searching.

Marcus contacted churches in the historic black neighborhoods of Charleston, reached out to genealogy groups, posted inquiries on ancestry forms.

Sarah continued examining the Dgerara type, discovering additional details she had initially missed.

Faint markings on the ver floorboards that might have been symbols.

The particular way Eliza’s collar was folded, possibly concealing something.

The angle of her head that kept her face partially shadowed, but ensured her hands remained visible.

The breakthrough came from a woman named Dorothy Bennett, a retired school teacher who belonged to the Gula Heritage Society.

She responded to Marcus’ inquiry with cautious interest.

Her great great-grandmother had been named Hannah Freeman.

Born enslaved on Edesto Island, daughter of a woman named Eliza who worked as a seamstress.

Dorothy had family stories passed down through generations, though some details had faded or become confused over time.

Sarah and Marcus met Dorothy at her home in the East Side neighborhood, a modest house filled with family photographs spanning generations.

Dorothy, 73 years old with silver hair and sharp, intelligent eyes, welcomed them with sweet tea and homemade cookies.

My grandmother used to tell me stories about Eliza, Dorothy said, settling into her armchair.

She called her Granny Liza the Brave.

Said she helped people find their way to freedom during slavery times.

Sarah showed Dorothy the Dgerayotype on her tablet, zoomed in on Eliza’s face.

Dorothy stared at the image for a long moment, her eyes filling with tears.

“That’s her,” she whispered.

“I always wondered what she looked like.

My grandmother said she was strong, had a face that didn’t show fear, even when she should have been afraid.

She touched the screen gently, tracing Eliza’s features with her finger.

Can you tell us what your grandmother said about Eliza’s activities? Marcus asked gently.

Dorothy nodded, composing herself.

Granny said Eliza was part of a network helping people escape.

She would get information from the big house, pass messages, hide people in the quarters when slave catchers came looking.

Once the war started, she helped Union soldiers who escaped from Confederate prisons, guided them to Union lines.

It was dangerous work.

If she’d been caught, she would have been sold away or worse.

Sarah showed Dorothy the hand signal in the photograph, explaining its significance.

Dorothy’s eyes widened, so she left proof.

She made sure the truth would survive somehow.

She stood and walked to a corner cabinet, retrieving an old wooden box.

I have something to show you.

It’s been in the family since Eliza’s time.

Dorothy opened the wooden box carefully, revealing its contents wrapped in faded cloth.

Inside was a small leatherbound journal, its pages yellowed and brittle with age.

Hannah, Eliza’s daughter, kept this, Dorothy explained.

She learned to read and write after emancipation at one of the schools the missionaries set up.

She wanted to record her mother’s story before it was lost.

Sarah’s hands trembled as she accepted the journal, handling it with the care of a professional conservator.

The first page born inscription in careful, formal handwriting.

The life and courage of my mother, Eliza Freeman, as told to me and witnessed by me, her daughter Hannah Freeman, written in Charleston, South Carolina, in the year of our Lord, 187.

Marcus positioned his phone to photograph each page as Sarah carefully turned them.

Hannah’s account began with her earliest memories of life on the Whitfield plantation, describing the daily routines, the fear that permeated every moment the careful masks enslaved people wore.

Then the narrative shifted to Eliza’s covert activities.

My mother was approached by a free black man named Samuel who worked on the docks in Charleston.

Hannah had written.

He asked if she would be willing to help people seeking freedom.

She said yes without hesitation.

Though she knew the danger, she began leaving signs, passing information, hiding people in the cellar beneath the sewing room where the white family never went.

The journal detailed specific escapes Eliza had facilitated.

A family of four guided to a safe house 3 mi north.

A young man provided with a map and supplies to reach Union lines.

A woman and her children hidden for a week while slave catchers searched the area.

Hannah recorded at least 15 escapes that Eliza had participated in between 1860 and 1865.

Then Sarah reached an entry dated August 1862 and her breath caught.

A traveling photographer came to take a picture of the Whitfield family Hannah had written.

Mother saw an opportunity.

She knew the photograph would last, would survive even if she did not.

She wore her Northstar pin hidden in the shadows where only someone looking closely would see it.

and she positioned her hands in the signal Samuel had taught her, the sign that meant freedom house.

She told me later she wanted to leave proof, a message that would outlive all of them so that one day people would know the truth.

Eliza had known exactly what she was doing.

The photograph was not accidental documentation, but deliberate testimony.

A message planted in the historical record like a time capsule waiting to be discovered.

The journal revealed much more than just Eliza’s underground railroad activities.

It documented a network of resistance far more extensive than historical records had suggested.

Eliza had worked with at least a dozen other conductors, including several house servants on neighboring plantations, a white Quaker family who operated a store in Charleston, and free black sailors who smuggled freedom seekers onto northbound ships.

Hannah described how her mother used her work as a seamstress to pass messages, sewing coded patterns into quilts and clothing, using specific thread colors and stitch patterns to communicate information about roots, timing, and dangers.

She detailed how Eliza would travel to Charleston on errands for the Whitfield family, using those trips to coordinate with other members of the network.

The entries also revealed the psychological toll.

Hannah wrote about nights when her mother would wake screaming from nightmares, about the constant fear of discovery, about the guilt Eliza felt when she couldn’t help everyone who needed it.

One passage described an incident in 1863 when a young man Eliza had helped was recaptured and beaten nearly to death as an example to others.

Eliza had blamed herself for months, though Hannah emphasized that her mother never stopped helping others despite the trauma.

Sarah and Marcus spent hours in Dorothy’s living room, photographing every page, taking notes, asking Dorothy to share additional family stories.

Dorothy told them about Eliza’s life after emancipation, how she had worked as a seamstress in Charleston, saving money to buy a small house, how she had helped establish one of the first schools for black children in the city, how she had lived to see her grandchildren born free.

She died in 1891.

Dorothy said.

Hannah wrote that she was peaceful at the end, proud of what she had accomplished.

The last thing she said was, “I kept them safe.

That’s what matters.

” Dorothy wiped her eyes.

For generations, we’ve told these stories at family gatherings, passed them down.

But most people outside the family didn’t believe us.

They’d say we were exaggerating, making ourselves seem more important than we were.

Now you have proof.

You have her own message left for the world to find.

Sarah looked at the Dgeray type again, seeing it with completely new understanding.

This wasn’t just a historical artifact.

It was evidence of extraordinary courage, of a woman who had risked everything to help others and who had been clever enough to document her resistance in a way that would survive more than 160 years.

The Charleston Heritage Museum held a press conference 6 weeks after Rob Sarah’s initial discovery.

The exhibition hall was packed with journalists, historians, community members, and Dorothy’s extended family.

The enlarged dgeray type dominated one wall with detailed annotations highlighting Eliza’s hand signal, the North Star pin, and other subtle messages Sarah had discovered through meticulous analysis.

Display cases held Hannah’s journal, carefully preserved and open to key passages alongside contemporary documents about the Underground Railroad in South Carolina.

Dr.

Johnson spoke first, providing historical context about the Underground Railroads operations in the Low Country, acknowledging how much of that history had been overlooked or minimized in traditional narratives.

Marcus presented the archival research, tracing Eliza’s life from enslavement through emancipation to her work as a teacher and community leader.

Then Sarah stepped to the podium, the restored dgerayotype displayed on the screen behind her.

“When I first scanned this photograph,” Sarah began, I thought I was looking at another piece of documentation of slavery.

Another portrait of a wealthy white family with enslaved people pushed to the margins.

I didn’t expect to find evidence of resistance, of courage, of a woman who used this very photograph as an act of defiance.

She detailed her process of discovery, explaining how enhanced imaging technology had revealed details invisible to the naked eye, how cross- refferencing with historical records and oral histories had built a comprehensive picture of Eliza’s activities.

Eliza Freeman was not a victim defined solely by her enslavement, Sarah continued.

She was a conductor on the Underground Railroad, a strategist, a hero who saved lives at tremendous personal risk.

and she was smart enough to leave us this message, knowing that one day, with the right technology and the right attention, someone would see what she had hidden in plain sight.

Dorothy approached the podium next, her voice strong despite her emotion.

My family has carried Eliza’s story for generations.

We’ve been told we were exaggerating, that we were making up tales to feel important.

Today, the evidence proves what we always knew.

Our ancestor was a hero.

She deserves to be remembered and honored, not just by our family, but by everyone who values freedom and justice.

The room erupted in applause.

Sarah watched as Dorothy’s children and grandchildren gathered around the enlarged photograph.

Some crying, some laughing, all of them touching the image of their ancestor with reverence and pride.

Journalists approached with questions.

Historians requested access to the journal and documents for further research.

A local filmmaker asked Dorothy if she would participate in a documentary about Eliza’s life.

3 months later, Sarah stood in the newly opened exhibition at the Charleston Heritage Museum titled Hidden in Plain Sight: Eliza Freeman and the Underground Railroad in South Carolina.

The exhibition had expanded far beyond the original Dgera type.

Working with Dr.

Johnson and community historians, they had uncovered additional evidence of the network Eliza had been part of.

property records showing safe houses, ship manifests documenting freedom seekers who had reached northern ports, letters from formerly enslaved people describing their escapes.

Other families had come forward with their own stories passed down through generations of ancestors who had participated in resistance activities.

The exhibition honored them all, correcting the historical record that had long minimized or ignored black agency and courage during slavery.

Schools brought students to see the displays, learning history that had been absent from their textbooks.

Dorothy visited the exhibition regularly, often finding her surrounded by visitors asking questions about Eliza.

She had become a sought-after speaker, sharing her family’s oral history with audiences who finally understood its significance.

Her grandchildren, initially skeptical about old family stories, now spoke about their ancestor with pride and had begun researching other aspects of their family history.

Sarah had continued her work on the Whitfield collection, discovering three more photographs where enslaved individuals had positioned themselves or objects in ways that now seemed clearly intentional.

Each discovery opened new questions, new investigations, new opportunities to restore forgotten voices to the historical record.

Standing before the enlarged dgerayotype, Sarah studied Eliza’s face once more, that careful, neutral expression that concealed so much determination and courage.

The hand signal was now immediately visible to every visitor, highlighted by discrete lighting and detailed explanations.

Children traced the position of Eliza’s fingers with their own hands.

Learning the sign that had once meant safe house or friend, keeping that knowledge alive for a new generation.

She wanted to be seen, a young girl said to her mother, standing beside Sarah.

She knew someday someone would look close enough to find her message.

The mother smiled, reading the exhibition text aloud.

And now we have.

Now everyone knows her name and what she did.

Sarah thought about all the other photographs sitting in archives and museums waiting to be examined with new technology and new perspectives.

How many other messages had been hidden by people who refused to let their stories be erased? How many other acts of courage and resistance were still waiting to be discovered, concealed in images that historians had glanced at and dismissed? The photograph was no longer just a dgerayotype of a wealthy white family on their plantation veranda.

It was Eliza Freeman’s testament, her proof of existence and resistance.

her gift to the future.

It had taken 162 years for someone to see what she had left behind.

But her message had survived.

Her courage had survived.

Her name would not be forgotten.

News

🚨 911 Calls “Released” in the Plane Crash Said to Have Killed NASCAR’s Greg Biffle and His Family—Static, Overlapping Voices, and a Timeline That Allegedly Doesn’t Add Up Ignite a Firestorm of Questions 😱 In a breathless tabloid cadence, the narrator teases purported audio fragments, dispatch confusion, and chilling pauses that feel longer than they should, urging viewers to listen between the lines where panic, protocol, and fate collide 👇

The Final Flight: A Shattering Legacy On a crisp January morning, the sun rose over the horizon, casting a golden…

🕯️ Tributes Pour In for NASCAR’s Greg Biffle After Reports of a Deadly Plane Crash—A Wave of Grief, Rumors, and Raw Emotion Collide as the Racing World Struggles to Process the Unthinkable 😱 In a hushed, dramatic narrator tone, the lead sketches candlelit tracks, stunned teammates posting through tears, and fans clinging to updates as heartfelt messages blur with unanswered questions, turning remembrance into a vigil where hope and heartbreak wrestle in real time 👇

The Final Lap: A Shocking Farewell to Greg Biffle In the quiet town of Statesville, North Carolina, the sun rose…

💔 “It’s Hard to Breathe Watching This”: NASCAR Fans Break Down After the Greg Biffle Plane Crash, as Shock Turns to Fear, Forums Flood With Tears, and the Racing World Faces a Moment It Never Prepared For 😱 In a raw, trembling narrator tone, the lead paints packed watch parties going silent, phones lighting up with the same four words, and longtime fans admitting this one cut deeper because it felt personal—like family shaken by an unseen hand 👇

The Final Lap: A Heartbreaking Farewell In a world where speed and glory collide, tragedy struck without warning. Greg Biffle,…

🚨 Greg Biffle 911 Calls EXPOSE the Most Terrifying Minutes After the NASCAR Legend’s Plane Went Down With His Family—Whispers of Panic, Static-Filled Pleas, and a Timeline That Refuses to Line Up 😱 In a breathless, cutting narrator voice, the story circles alleged call fragments, frantic voices bleeding through interference, and the chilling realization that the scariest part wasn’t the impact but what happened after, as responders raced clocks, weather, and disbelief 👇

The Descent of a Legend: A Shocking Revelation In the quiet town of North Carolina, the sun rose with an…

✈️ Greg Biffle Plane Crash Update: The “72-Hour Rule” That Saves Lives—A Chilling Countdown Experts Say Separates Close Calls From Catastrophe as New Aviation Lessons Hit Hard 😱 In a sharp, dramatic cadence, the narrator leans into cockpit psychology, fatigue windows, and the quiet decisions made after the headlines fade, suggesting that what pilots do—or don’t do—in the three days after a scare can mean the difference between a safe return and a nightmare nobody wants to relive 👇

The Last Flight of Greg Biffle: A Journey into Darkness Greg Biffle stood at the edge of the tarmac, staring…

Tragic Greg Biffle Audio Released: What’s Really Hidden in the Heart-Wrenching Tape? 😱🎧 In a shocking turn of events, the tragic audio from Greg Biffle’s crash has been released, sending shockwaves through the racing world. As the haunting sounds fill the airwaves, questions arise: what did we just hear? Was this the final moments of a champion’s life, or is there more to this tape than meets the eye? Get ready for a raw, unfiltered look at the tragedy that left everyone on edge.

This audio could change everything we thought we knew about the crash.

👇

The Fall of a Legend: The Tragic Descent of Greg Biffle In a world where heroes rise and fall, few…

End of content

No more pages to load