The Plantation Owner Mocked His Slave’s Dream of Freedom, Until It Cost Him His Life

Welcome to this journey through one of the most unsettling cases documented in United States history.

Before we begin, I invite you to leave in the comments where you’re watching from and the exact time at which you’re listening to this narration.

We’re interested to know how far and at what times of day or night these documented accounts reach.

The year was 1834 when the events that would forever change the lives of those on the Caldwell Plantation began to unfold.

Located in Tolbert County, Maryland, nestled against the eastern shore of the Chesapeake Bay, the plantation sat like a silent witness to the countless injustices that defined that era.

The main house stood on a gentle rise overlooking acres of tobacco fields that stretched toward the water.

The crops cultivated by dozens of enslaved individuals whose names have largely been erased from history.

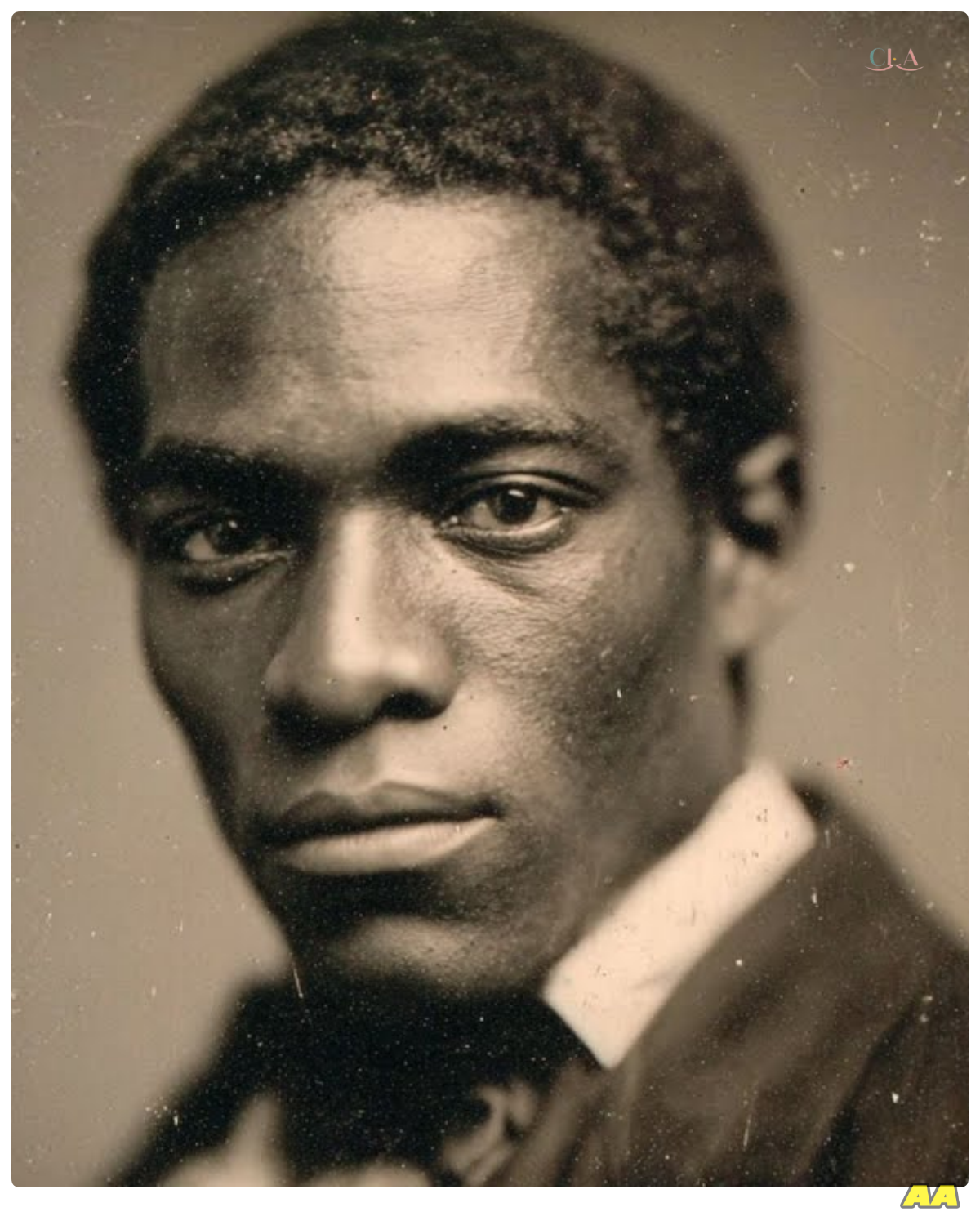

All except for one, Samuel Green.

Samuel Green was not the name he was born with.

That name had been taken from him 20 years earlier when William Caldwell purchased him at auction in Baltimore.

Samuel was then a young man of 18 years, strongbacked and cleareyed, despite the horrors he had already witnessed in his short life.

William Caldwell saw only the potential labor in Samuel’s broad shoulders, the decades of work his body could provide before breaking down.

But beneath Samuel’s careful expression lay a mind that observed, calculated, and remembered everything.

The Caldwell plantation was considered moderately successful by the standards of Maryland’s Eastern Shore.

William Caldwell had inherited the land from his father, James Caldwell, who had acquired it in the late 1700s during the postrevolutionary expansion.

The main house was a two-story brick structure with white columns supporting a wide porch that wrapped around three sides of the building.

Behind it stood the kitchen house, the smokehouse, and further back, hidden from view of visitors arriving via the long oakline drive, the slave quarters.

A collection of crude wooden structures where Samuel and 23 other enslaved people lived in conditions that William Caldwell never bothered to inspect.

William’s wife, Elizabeth Caldwell, had died in childbirth 5 years before our story begins, taking with her their stillborn son, and any softness that might have remained in William’s character.

Since then he had grown increasingly bitter, his cruelty toward those he owned becoming more pronounced with each passing season.

The neighboring plantation owners spoke of his change in temperament in hush tones at their social gatherings, attributing it to grief, while secretly wondering if the darkness had always been there, merely waiting for an excuse to emerge.

By 1834, William Caldwell had gained a reputation throughout Tolbert County for his harsh treatment of his human property.

The local physician, Dr.

Thomas Harrison had been called to the plantation on numerous occasions to treat injuries that could not be explained by accidents alone.

But in an era and place where enslaved people were viewed as property rather than human beings, no one intervened.

The law protected William Caldwell’s right to do as he pleased with those he owned, and the community’s moral compass had long been warped by economic interests and racial prejudice.

Samuel Green had survived a decade on the Caldwell plantation by making himself indispensable.

Intelligent and observant, he had learned to read despite the laws forbidding literacy among enslaved people.

He kept this knowledge hidden, understanding that such a discovery would lead to severe punishment or worse.

At night, by the dim light of candle stubs he had collected from the main house, Samuel would read whatever scraps of newspapers or discarded books he could find, absorbing information about the world beyond the plantation boundaries.

It was through these stolen moments of reading that Samuel learned about the growing abolitionist movement in the north, about free black communities in places like Philadelphia and New York, about the Underground Railroad that helped enslaved people escape to freedom.

These fragments of knowledge took root in his mind, growing into a dream that became more vivid with each passing day.

The dream of freedom.

Samuel was not alone in this yearning.

Among the enslaved community on the Caldwell plantation was a woman named Martha Turner.

Martha had been at the plantation longer than Samuel, arriving as a child when William Caldwell’s father still ran the operation.

Now in her early 30s, Martha had survived by becoming essential to the functioning of the main house, serving as cook and housekeeper.

Like Samuel, she had secretly learned to read and write, taught by Elizabeth Caldwell before her death.

William never discovered this arrangement, and after his wife passed, Martha carefully concealed her literacy.

Samuel and Martha formed a bond built on their shared secret knowledge and mutual desire for freedom.

Their conversations always conducted in whispers away from potential informants, centered around plans and possibilities.

They collected information methodically, the patterns of the overseers rounds, which neighbors might be sympathetic, the schedule of boats traveling north on the Chesapeake, the safest routes through the woods surrounding the plantation.

They knew that escape would be dangerous, possibly fatal if they were caught.

But the risk seemed increasingly worth taking as William Caldwell’s behavior grew more erratic and violent.

In the spring of 1834, an opportunity presented itself.

William Caldwell received a visitor from Baltimore, a tobacco merchant named James Rutled, with whom he had done business for years.

Rutled was a tall, imposing figure with the confident heir of a successful businessman.

At 50 years old, his hair had turned silver at the temples, but his eyes remained sharp, missing nothing as they surveyed the plantation during his 3-day stay.

Unlike many of the merchants who dealt with the Maryland planters, Rutlage was known to express moderate views on slavery, having publicly stated that the institution would eventually need to end, though he believed in gradual compensated emancipation rather than immediate abolition.

Samuel was assigned to attend to Rutled during his visit, bringing his luggage to the guest room, ensuring his horse was properly cared for, and standing by to fulfill any requests.

It was in this capacity that Samuel first heard Rutled express his views on the future of slavery in America as he conversed with William Caldwell over dinner on the first evening of his stay.

The writing is on the wall, William, Rutled said, his voice carrying through the open dining room window to where Samuel stood in the shadows of the porch.

The pressure from the north grows stronger each year.

England has already abolished slavery in most of its colonies.

We would be wise to prepare for the inevitable changes.

William Caldwell’s response was immediate and harsh.

The British can do as they please with their colonies.

Here in Maryland, we understand the natural order of things.

My father built this plantation with slave labor, as did his father before him.

I will not apologize for continuing what they began.

I’m not suggesting you apologize, Rutled replied, his tone measured.

Merely that you consider the direction in which the wind is blowing.

Many planters are already transitioning to paid labor, finding it more economical in the long run.

The cost of maintaining enslaved workers, particularly as they age, often exceeds what one would pay in wages.

And who would work my fields if not the slaves I own? William demanded.

Free blacks.

They would demand too much and work too little.

Immigrants, they come with ideas about equality that have no place here.

The conversation continued in this vein throughout the evening, with Rutled making economic arguments for gradual emancipation, and William Caldwell stubbornly defending the institution that provided his wealth and status.

Samuel absorbed every word, his mind racing with the implications.

Here was a white man of means and influence openly discussing the end of slavery, even if his timeline was longer than Samuel wished.

Later that night, as Samuel discussed what he had overheard with Martha, a plan began to form.

Rutled would be at the plantation for two more days.

If Samuel could somehow appeal to him directly, perhaps the merchant might help facilitate their escape.

It was a desperate gamble, but the alternative, remaining under William Caldwell’s increasingly unpredictable authority, seemed worse with each passing day.

The next morning, Samuel found a moment alone with Rutled, as the merchant inspected the tobacco fields.

William Caldwell had been delayed at the main house by the arrival of a neighbor, giving Samuel the opportunity he needed.

Sir,” Samuel said quietly, approaching Rutled with his eyes appropriately lowered as was expected.

“I heard what you said last night about the future of our situation.

” Rutled looked surprised, but not angry.

“You were listening to our conversation?” “Not by choice, sir.

I was attending to my duties on the porch.

” This was a partial truth, as Samuel had deliberately positioned himself to overhear.

I see.

And what did you make of it? Rutled asked, his curiosity apparently overcoming any offense at being eavesdropped upon.

Samuel took a deep breath, weighing his words carefully.

I believe you’re right, sir.

Change is coming.

I’ve heard talk of it from others who pass through.

And I’ve heard of places in the north where men like me can live free.

Rutled studied Samuel’s face closely.

You’re an intelligent man, aren’t you? more so than Caldwell realizes, I suspect.

Samuel remains silent, unsure how to respond to this observation.

“Can you read?” Rutlidge asked suddenly, lowering his voice.

The question was dangerous.

Admitting literacy could result in severe punishment, but Samuel sensed this might be his only chance.

“Yes, sir, I taught myself.

” A look of genuine respect crossed Rutled’s features.

impressive and dangerous knowledge in these parts.

Sir, Samuel said, emboldened by Rutled’s response, I dream of freedom, not just for myself, but for others here, especially Martha, who works in the house.

We’ve been planning, but we need help to get north.

Rutled’s expression changed, growing more guarded.

You’re asking a great deal, Samuel.

What you suggest is illegal.

I could lose my business, my standing in society.

You spoke of inevitable change last night, Samuel pressed, knowing he might never get another opportunity like this.

You spoke of preparation.

I was talking about gradual economic transitions, not illegal flight of property, Rutled replied, though his tone lacked conviction.

Are we merely property, sir, or are we human beings? Samuel asked, daring to look directly into Rutled’s eyes.

Before Rutled could respond, they heard William Caldwell’s voice calling from the direction of the main house.

The merchant quickly stepped back from Samuel.

“We will speak no more of this,” he said quietly.

“Return to your duties.

” Samuel’s heart sank, but he had no choice but to comply.

As he turned to leave, Rutlidge added in a whisper, “Meet me by the stables at midnight, “Bring only what you absolutely need.

” That evening, Samuel and Martha prepared for their escape with a mixture of hope and terror.

They told only two others of their plan, an elderly couple named Isaiah and Ruth Brooks, who had been on the plantation since its beginning, and who would cover for their absence as long as possible.

The four embraced in the darkness of the slave quarters, tears streaming down their faces as they acknowledged they might never see each other again.

At midnight, Samuel and Martha slipped away to the stables, carrying small bundles containing the few possessions they could not bear to leave behind.

A wooden carving Samuel had made of his mother, whom he had not seen since childhood, a scrap of fabric from a dress Elizabeth Caldwell had given Martha.

a small knife, some dried food, and a crude map Samuel had drawn based on descriptions of the route north.

“James Rutled was waiting for them as promised, his face grim in the moonlight.

My wagon is behind the tobacco barn,” he whispered.

“I’ve created a false bottom where you can hide.

I’m leaving for Baltimore at dawn.

Caldwell believes I’m departing a day early due to business concerns.

” Thank you, sir, Martha whispered, her voice trembling with emotion.

Don’t thank me yet, Rutled replied.

The journey will be dangerous, and I can only take you as far as Baltimore.

From there, you’ll need to connect with others who can guide you north.

We understand, Samuel said.

We’re prepared for whatever comes.

Rutled nodded solemnly.

Then hide in the barn until I come for you at first light, and pray we are not discovered.

The hours until dawn passed with excruciating slowness.

Samuel and Martha huddled together in the darkness of the tobacco barn, listening for any sound that might indicate discovery.

They spoke in whispers about the future they hoped to build, about the possibility of reaching Philadelphia or beyond, about someday helping others escape as they were being helped.

Despite the danger, there was a sense of exhilaration in taking this step toward freedom.

After years of forced submission, as the first hint of dawn lightened the eastern sky, they heard approaching footsteps and tensed, ready to flee if necessary.

But it was rutled, his expression tense, as he gestured for them to follow him quickly to the waiting wagon.

The false bottom he had constructed was cramped, but would conceal them from casual inspection.

As they prepared to climb inside, a voice cut through the pre-dawn stillness.

I believed better of you, Rutled.

William Caldwell stood 20 yards away, a shotgun aimed at the merchant’s chest.

His face was a mask of cold fury in the dim light.

Step away from my property, Caldwell continued, advancing slowly.

I had my suspicions when you announced your early departure.

It seems they were wellfounded.

“Be reasonable, William,” Rutled said, his hands raised plecatingly.

“The world is changing.

These people deserve.

They are not people, Caldwell interrupted, his voice rising.

They are my property.

Same as this land.

Same as the tobacco they cultivate.

And you are attempting to steal from me.

Samuel moved protectively in front of Martha, his mind racing for a solution.

Rutled continued trying to reason with Caldwell, but it was clear from the plantation owner’s expression that he was beyond rational discussion.

His face was flushed with rage, spittle flying from his lips as he ranted about betrayal and the natural order.

What happened next occurred with such speed that later accounts would differ in the details.

William Caldwell, gesturing wildly with the shotgun, stepped forward and stumbled on an uneven patch of ground.

The gun discharged, the shot going wide, but spooking the horses hitched to Rutlidge’s wagon.

As the animals reared in panic, Caldwell lost his balance completely and fell.

Samuel rushed forward, intending to disarm him before he could recover, but Caldwell was already rising, swinging the shotgun like a club toward Samuel’s head.

Samuel raised his arm defensively, and the impact of the gun barrel sent a shock of pain through his body.

He grappled with Caldwell, both men falling to the ground in a desperate struggle for the weapon.

Martha screamed for them to stop while Rutled attempted to calm the frightened horses and simultaneously moved to separate the fighting men.

The shotgun discharged a second time.

When the echo of the blast faded, an unnatural silence fell over the scene.

William Caldwell lay motionless on the ground, a spreading crimson stain visible on his chest, even in the dim light.

Samuel stood over him, the shotgun now in his hands, his expression one of horror and disbelief.

God in heaven, Rutled whispered, looking from Caldwell’s body to Samuel.

I didn’t mean, Samuel began, but his voice failed him.

It doesn’t matter what you meant, Rutled said urgently.

A black man has killed a white plantation owner.

There’s no explanation that will save you now.

What do we do? Martha asked, her voice surprisingly steady despite the catastrophe unfolding before them.

Rutled was silent for a long moment, clearly weighing impossible options.

Finally, he spoke.

Get in the wagon now.

We need to be miles from here before the body is discovered.

Samuel hesitated, looking down at the shotgun in his hands and then at Caldwell’s lifeless form.

“Samuel,” Martha said softly, taking his arm, “we have to go.

This is our only chance now.

” With a numb nod, Samuel allowed her to lead him to the wagon.

Rutled quickly covered all traces of the struggle, then helped them into the hidden compartment.

Within minutes they were traveling down the long drive of the Caldwell plantation, leaving behind the only life they had known, and a dead man whose final expression had been one not of pain, but of shocked disbelief, that his absolute authority had been so suddenly and completely ended.

The journey to Baltimore passed in a blur of fear and confusion.

Samuel replayed the confrontation with Caldwell countless times in his mind, trying to understand how events had spiraled so catastrophically out of control.

Had he pushed the gun toward Caldwell during their struggle? Had Caldwell’s finger been on the trigger, the uncertainty was a torment worse than any physical punishment he had endured on the plantation.

Martha, sensing his anguish, held his hand in the darkness of their hiding place.

It was an accident, she whispered.

You were defending yourself.

That won’t matter, Samuel replied, his voice hollow.

A white man is dead, and I held the gun.

They’ll hang me if they find us.

Then they must not find us, she said with quiet determination.

When they reached Baltimore, Rutled brought them to a modest house in a secluded area of the city.

The woman who answered his knock was introduced only as Rachel, a Quaker who was known to assist those seeking freedom on the Underground Railroad.

Rutled explained the situation in hush tones while Samuel and Martha waited anxiously, certain that at any moment authorities would appear to arrest them for Caldwell’s death.

Rachel’s expression remained composed as she absorbed the gravity of their situation.

The news will spread quickly, she said.

Every slave catcher and bounty hunter in Maryland will be searching for you once word reaches Baltimore.

You cannot stay here long.

I’ve risked enough, Rutlitch said, not meeting Samuel’s eyes.

My involvement ends here.

Rachel nodded, seemingly unsurprised by his decision.

You’ve done more than most would, James.

Go with a clear conscience.

After Rutlidge departed, Rachel led Samuel and Martha to an attic room where they could rest while she made arrangements for the next stage of their journey.

“Sleep if you can,” she advised.

“Tomorrow night you’ll travel again, and it may be many days before you have another chance for proper rest.

” But sleep was impossible for Samuel.

The events of the morning haunted him.

Caldwell’s face as the shot rang out.

The sudden lifelessness of the man who had controlled his existence for so many years, the blood soaking into the ground of the plantation that had been his prison.

He had dreamed of freedom for so long, but not like this.

Not with the weight of a man’s death, however accidental, on his conscience.

Martha dozed fitfully beside him, occasionally murmuring in her sleep, her brow furrowed with concern, even in unconsciousness.

Samuel watched over her, grateful for her unwavering presence in the chaos their lives had become.

Whatever happened next, they would face it together.

The following evening, Rachel introduced them to a man named John Parker, a free black conductor on the Underground Railroad, who would guide them to the next safe house.

Parker was a powerfully built man with watchful eyes and few words, but his competence was evident in the efficient way he organized their departure.

“We’ll travel by night, rest by day,” he explained as they prepared to leave Rachel’s house under cover of darkness.

“There are safe houses every 15 to 20 m along our route, but the journey will still be dangerous.

The news of what happened at the Caldwell plantation has already reached Baltimore.

There’s a substantial reward offered for your capture.

Samuel nodded grimly, having expected nothing less.

William Caldwell had been a prominent figure in Tolbert County, and his death, especially at the hands of an enslaved person, would not go unpunished.

Their journey north was a gauntlet of terrors.

Hiding in swamps when slave patrols passed nearby.

Crossing rivers in small boats during stormy nights when the water was too rough for pursuit.

Sleeping in root sellers and attics of sympathetic households who risked everything to shelter them.

Each day brought new dangers.

Each night new trials as they pushed steadily northward through Maryland into Pennsylvania.

As they traveled, Samuel and Martha heard whispers of the growing manhunt behind them.

The story of Caldwell’s death had spread, growing more sensational with each retelling.

In some versions, Samuel had deliberately murdered his master in cold blood.

In others, he had led a violent revolt that threatened to spread to neighboring plantations.

The truth, a desperate struggle resulting in an accidental death, was lost amid the fear and prejudice that colored every account.

3 weeks after their flight from the Caldwell Plantation, they reached Philadelphia, crossing into the city under cover of a thunderstorm that seemed providentially timed to mask their arrival.

Their guide brought them to a small church in a predominantly black neighborhood where they were met by a minister named Reverend William Johnson.

“You’re safe for the moment,” Reverend Johnson told them after hearing their story.

“But Pennsylvania isn’t secure enough given the circumstances.

Slave catchers operate openly here despite the state laws against slavery.

We need to move you further north to New York or Massachusetts, perhaps even to Canada.

How long before we can move on? Martha asked, exhaustion evident in her voice despite her determination.

A few days at most, the reverend replied.

I have contacts preparing for your arrival, but arrangements take time, especially in a case as complicated as yours.

Samuel understood the unspoken concern.

Harboring fugitive slaves was already dangerous.

Harboring a fugitive accused of killing his master was exponentially more so.

Everyone who helped them was at risk, a fact that weighed heavily on Samuel’s conscience.

During their brief stay in Philadelphia, Samuel and Martha were housed in a small room beneath the church, venturing out only at night and always in disguise.

On their third evening in the city, Reverend Johnson brought them a newspaper from Baltimore.

The front page carried an account of William Caldwell’s death and the subsequent manhunt for his murderer.

Samuel read the article with growing horror.

According to the report, evidence had been discovered suggesting he had been planning the murder for months.

Letters supposedly found in the slave quarters indicated a broader conspiracy involving other enslaved people on neighboring plantations.

The article named Martha as his accomplice and James Rutled as an unwitting dupe in their escape.

Most disturbing of all was the news that Isaiah and Ruth Brooks, the elderly couple who had bid them farewell on the night of their escape, had been publicly whipped for failing to report the conspiracy.

With Isaiah succumbing to his injuries days later.

“None of this is true,” Samuel said, his hands shaking as he set down the paper.

There were no letters, no conspiracy.

and Isaiah and Ruth knew nothing beyond our plans to escape.

“Truth is often the first casualty when powerful interests are threatened,” Reverend Johnson replied solemnly.

“William Caldwell’s death frightened many plantation owners.

” “The story of a calculated murder plot serves their purposes better than an accidental death during an escape attempt.

” Martha took Samuel’s hand, her eyes filled with tears for the innocent people suffering because of their flight.

“We can’t change what happened,” she said softly.

“All we can do now is survive and make our freedom mean something.

” The next day, Reverend Johnson informed them that arrangements had been finalized for the next leg of their journey.

They would travel north that very night, making their way to Albany, New York, where a community of abolitionists had prepared a more permanent refuge.

From there, depending on the intensity of the pursuit, they might continue to Canada.

As they prepared to depart, Samuel was struck by a realization.

“We need different names,” he said to Martha.

“Samuel Green and Martha Turner must disappear completely.

” She nodded in understanding.

The names they had been given as enslaved people were part of their bondage, assigned by those who claimed ownership over them.

In freedom, they would choose their own identities.

From this day forward, I am Benjamin Freeman, Samuel declared, the symbolism of the surname not lost on either of them.

Martha considered for a moment before saying, “And I will be Grace.

Grace Freeman.

” Reverend Johnson recorded their new names in a small book he kept hidden beneath a floorboard in his office, a registry of those who had passed through on their journey to freedom.

“Benjamin and Grace Freeman,” he repeated, a sad smile crossing his face.

“May your new names bring you the peace and dignity you deserve.

” That night they left Philadelphia with a new guide, a white woman named Sarah Bradford, who transported them hidden in her covered wagon, concealed beneath sacks of grain she was ostensibly delivering to markets along the route north.

The journey to Albany took over a week with several close calls when patrols searched wagons at checkpoints along the major roads.

By the time they reached Albany in midJune of 1834, the immediate furer over William Caldwell’s death had begun to subside, though the reward for their capture remained in effect.

The abolitionist network in Albany, led by a former Quaker named Thomas Wilson, helped establish Benjamin and Grace in a small house on the outskirts of the city.

Wilson owned a printing shop and offered Benjamin work setting type, a skill he quickly mastered thanks to his secret literacy.

For the first time in their lives, Benjamin and Grace experienced a tentative freedom.

They married in a small ceremony performed by a sympathetic minister, worked for wages, and began to build a life that had seemed impossible just months before.

Yet the shadow of the past hung over them constantly.

Each unexpected knock at the door brought a surge of terror.

Each new arrival from the south was questioned carefully about news from Maryland and the ongoing search for Samuel Green and Martha Turner.

In October of that year, Thomas Wilson brought them news that William Caldwell’s plantation had been sold following his death.

The enslaved people auctioned to various buyers throughout Maryland and Virginia.

There was no word of Ruth Brooks, and Benjamin and Grace feared she too had perished, another victim of their desperate bid for freedom.

The guilt weighed particularly heavily on Benjamin, who sometimes woke in the night, calling out for Isaiah and Ruth, reliving the moment of parting in his dreams.

As autumn gave way to winter, the immediate danger seemed to recede somewhat.

The abolitionists in Albany believed that with the passage of time and the dispersion of those who had known them at the Caldwell plantation, Benjamin and Grace might eventually be safe from discovery.

Still, they remained vigilant, aware that a single moment of carelessness could destroy everything they had built.

In January of 1835, Grace discovered she was with child.

The news brought both joy and fear.

Joy at the prospect of a child born into freedom.

Fear that this new responsibility would make them more vulnerable if they needed to flee again.

Benjamin threw himself into his work at the printing shop, saving every penny to prepare for the baby’s arrival and the possibility that they might need to move further north on short notice.

Their son was born in August of 1835, a healthy boy they named Isaiah in honor of the man who had sacrificed his life for their freedom.

As Grace recovered from the birth, Benjamin spent hours simply watching his son sleep, marveling at the tiny hands and peaceful expression of a child who would never know the lash or the auction block, who would grow up with his name as his own possession rather than that of a master.

For nearly two years, they lived in this state of cautious happiness, building connections within Alby’s free black community and the circle of white abolitionists who supported them.

Benjamin’s skill as a type setter led to increased responsibility at Wilson’s print shop, where he began to assist with the publication of abolitionist pamphlets and newspapers.

Grace, with baby Isaiah strapped to her back, took in laundry and sewing to supplement their income.

Then in the spring of 1837, their fragile piece was shattered.

A new family had arrived in Albany from Baltimore, and the husband, a carpenter named William Barnes, began working at a shop near Wilson’s printing business.

One afternoon, as Benjamin was delivering completed pamphlets to a nearby church, he and Barnes passed each other on the street.

There was a moment of mutual recognition, a flash of shock in Barnes’s eyes that confirmed Benjamin’s worst fear.

This man knew who he was.

Barnes had been a free black artisan who had occasionally done work at the Caldwell plantation.

He had seen Samuel Green many times, and though years had passed, and Benjamin’s appearance had changed somewhat, he now wore a full beard, and dressed in the manner of northern working men.

The carpenter had recognized him.

Benjamin returned to the print shop in a state of barely controlled panic, explaining the situation to Thomas Wilson.

The printer immediately sent word to Grace, who fled their small house with Isaiah, taking refuge with a Quaker family at the edge of town, while Wilson attempted to assess the threat.

Did Barnes intend to report them? Was he aware of the reward still offered for their capture? Would he recognize the connection between Benjamin Freeman and the fugitive Samuel Green? Wilson approached Barnes the following day, inviting him to a private conversation at the print shop after hours.

The discussion that followed was tense, with Barnes initially denying any recognition before finally admitting that he believed Benjamin to be the fugitive from Maryland.

“I have no intention of reporting him,” Barnes assured Wilson.

“I left the South to escape such injustice myself, but others might not be so understanding.

” There are those newly arrived from Baltimore who knew of the Caldwell case and might recognize him as I did.

Wilson, grateful for Barnes’s discretion, but alarmed by the wider implications, brought this news to Benjamin and Grace that evening.

It’s no longer safe for you here.

He told them gently, “If one person has recognized you, others may as well.

We need to move you further from danger.

” And so once again, Benjamin and Grace found themselves preparing for flight, packing the few possessions they had accumulated during their time in Albany, and saying painful goodbyes to the community that had sheltered them, Wilson arranged for them to travel to Montreal, Canada, where British law ensured they would be beyond the reach of American slave catchers and bounty hunters.

The journey north was made more difficult by the presence of 2-year-old Isaiah, whose innocent questions about why they needed to leave their home pierced his parents’ hearts.

They traveled by night when possible, following the network of safe houses that extended into Canada.

Their progress slowed by the need to keep Isaiah quiet and comfortable during the long hours of hiding and waiting.

They reached Montreal in late June of 1837 where they were met by representatives of the city’s small but growing community of freed slaves who had fled the United States.

A modest apartment was found for them and Benjamin was introduced to the owner of a print shop who upon seeing samples of his work from Albany immediately offered him employment.

Life in Montreal brought new challenges.

A different language, a harsher climate, the greater distance from the abolitionist networks they had come to rely upon.

But it also brought a deeper sense of security.

Here, at last, they were truly beyond the reach of those who would return them to bondage or exact punishment for William Caldwell’s death.

Isaiah could play in the small yard behind their apartment without his parents constantly scanning the street for unfamiliar faces.

Grace could shop in the local market without wearing a disguise to alter her appearance.

As the years passed, their family grew.

A daughter, Ruth, was born in 1839, followed by another son, James, in 1842.

Benjamin advanced from type setter to compositor at the print shop, eventually saving enough to purchase a small press of his own, which he operated from a workshop attached to their home.

Grace established a dress making business that catered to the wives of Montreal’s merchants, her skilled needle work, earning her a reputation that brought a steady stream of customers.

They told their children carefully edited versions of their past, explaining that they had escaped from slavery, but omitting the circumstances of William Caldwell’s death.

Those details, they agreed, would be shared only when the children were old enough to understand the desperate situation that had led to such a tragedy.

In the summer of 1850, a letter arrived from Thomas Wilson in Albany, containing news that sent a chill through Benjamin, despite the warm Canadian day.

James Rutled, the merchant who had attempted to help them escape, and who had brought them to Baltimore after Caldwell’s death, had died the previous winter.

on his deathbed, apparently seeking to clear his conscience, Rutled had made a full confession about the events of that morning at the Caldwell plantation.

According to Wilson’s letter, Rutled’s account largely corroborated Benjamin’s version of events, the struggle, the accidental discharge of the shotgun, the absence of any conspiracy or premeditated murder.

The deathbed confession had been documented by a lawyer and a minister, but it had not changed the official narrative that had calcified in the years since.

Samuel Green was still considered a murderer with a price on his head.

Still subject to capture and summary execution should he ever return to the United States.

Benjamin read the letter several times before showing it to Grace.

Part of him had hoped that Rutled’s testimony might somehow clear his name, might allow them to someday return to the United States, where the abolitionist movement was gaining strength.

But that hope, he now realized, had been naive.

The truth of what happened that day would never matter as much as the story that had been constructed afterward.

A story that served the interests of those who feared what might happen if enslaved people believed they could fight back against their masters and escape the consequences.

“We’ve built a good life here,” Grace said softly after reading the letter.

“Perhaps this is where we were always meant to be.

” Benjamin nodded, gazing out the window at Isaiah, now 17, who was teaching 7-year-old James how to repair the fence around their small garden.

Ruth at 11 sat nearby reading a book, her expression serious as she concentrated on the words.

These children, born free and raised with the expectation of dignity and respect, were the living embodiment of what he and Grace had risked everything to achieve.

I still dream about it sometimes, he admitted.

Caldwell falling, the gun going off, the look in his eyes.

I never wanted him to die.

I know, Grace said, taking his hand.

But his death gave life to all of this.

She gestured to the home they had built, to their children in the yard, to the evidence of their hard one freedom surrounding them.

And perhaps in some way we can’t understand, that was always how it needed to be.

Benjamin kept Wilson’s letter, storing it carefully in a metal box along with other documents from their journey.

the marriage certificate from Albany, the birth records of their children, letters from abolitionists who Benjamin kept Wilson’s letter, storing it carefully in a metal box along with other documents from their journey, the marriage certificate from Albany, the birth records of their children, letters from abolitionists who had helped them along the way.

These papers were a tangible record of their transformation from Samuel Green and Martha Turner, enslaved people owned by William Caldwell to Benjamin and Grace Freeman, free citizens building a life in Montreal.

As the years passed, their children grew into adulthood, each forging their own path in a world that, while still deeply flawed and prejudiced, offered them opportunities their parents had been denied.

Isaiah, the oldest, showed an aptitude for mechanical work and became an apprentice to a successful wheelright.

Ruth inherited her mother’s skill with needle and thread, eventually taking over the dress making business as Grace’s eyesight began to fail in her 50s.

James, the youngest, shared his father’s love of words and books, working alongside Benjamin in the print shop while studying law in the evenings under the tutelage of a sympathetic attorney.

In 1861, news reached them of the outbreak of civil war in the United States.

The conflict that many had predicted for decades had finally erupted with slavery as its central issue.

Benjamin followed the reports avidly, reading every newspaper account he could find, sometimes staying up late into the night discussing the war’s progress with James, who at 19 had developed strong opinions about justice and equality.

“Do you ever think about going back?” James asked one evening as they cleaned the press after a long day of work.

If the North winds and slavery truly ends, Benjamin paused, his hands stilling on the metal type he had been arranging.

I’ve thought about it, he admitted, but the America I fled still exists.

War or no war.

The hatred that made us fugitives didn’t disappear because armies are fighting.

James nodded thoughtfully.

Isaiah says some of the men he works with are talking about going south to join the Union Army.

They say it’s a chance to fight for our people’s freedom.

Your brother has a good heart, Benjamin replied.

But his life is here now.

All our lives are here.

The conversation weighed on Benjamin’s mind in the days that followed.

He had built a good life in Montreal, a life of dignity, security, and modest prosperity.

Yet there remained a part of him that longed for closure, for some acknowledgment of the injustice he had endured, and the accident that had forced him to flee his homeland.

In the fall of 1863, that longing was unexpectedly addressed when a letter arrived from Philadelphia, forwarded through Thomas Wilson in Albany.

The sender was Rachel, the Quaker woman who had sheltered Benjamin and Grace in Baltimore nearly 30 years earlier.

Now elderly, Rachel wrote that she had never forgotten them and had followed their case over the years.

She had recently encountered information that she felt they should know.

According to Rachel’s letter, a Union officer named Colonel Edward Thompson had occupied the former Caldwell Plantation, which was now being used as a temporary headquarters and hospital for Union troops.

While exploring the main house, Thompson had discovered a hidden compartment in William Caldwell’s desk containing a journal that spanned the years 1830 through 1834.

The journal, which Thompson had shared with Rachel due to her known abolitionist activities, contained entries that painted a disturbing picture of Caldwell’s mental state in the months before his death.

He described increasingly violent fantasies about punishing those he owned, particularly Samuel, whose intelligence he had recognized and had come to fear.

The final entry dated just 3 days before his death contained a chilling passage.

Green continues to watch me with those knowing eyes.

He thinks I don’t see how he studies the newspapers when he thinks no one is looking.

He believes himself clever, but I know what he plans.

I will not wait for him to act.

Better to make an example now before the others follow his lead.

Rachel wrote that Colonel Thompson had been sufficiently troubled by the journal to conduct interviews with elderly people in the area who remembered the Caldwell plantation.

One former overseer, now in his 70s, admitted that William Caldwell had been planning to sell Samuel to a notoriously brutal plantation in Louisiana, separating him from Martha, whom Caldwell intended to keep at the Maryland plantation.

The sale had been arranged for the day after James Rutled’s scheduled departure.

I share this information not to reopen old wounds, Rachel wrote, but to confirm what you have likely always known, that your escape that morning was truly a matter of life and death, and that what happened during the struggle was an act of self-defense in the most profound sense.

Benjamin read the letter aloud to Grace that evening after the children had gone to their own homes.

They sat together in silence for a long time afterward, absorbing the confirmation of the danger they had sensed, but never fully known during those final days on the plantation.

“He would have separated us,” Grace said finally, her voice steady despite the emotion in her eyes.

“Sold you away to die in Louisiana.

Kept me there alone.

” Benjamin nodded, remembering Caldwell’s erratic behavior in the weeks before their escape.

the strange way he had sometimes stared at Samuel with a mixture of fear and hatred.

“We knew something was wrong.

We just didn’t know what.

” “And now,” Grace asked, “does knowing this change how you feel about what happened?” Benjamin considered the question carefully, “It doesn’t change what happened.

A man died because of my actions, however, but perhaps it changes how I can live with it.

” Caldwell made his choice when he decided to sell me away from you.

When he came at us with that shotgun, he chose that ending, not me.

The American Civil War ended in 1865, and with it legal slavery in the United States.

Benjamin and Grace followed the news of reconstruction with cautious optimism, heartened by reports of freed men voting and holding office in the South, but concerned by the backlash that quickly emerged.

Their children, particularly James, who had become increasingly involved in discussions about racial equality, pressed them to consider returning to the United States now that slavery had been abolished.

The journal proves father acted in self-defense, James argued during a family dinner in 1867.

And the statute of limitations for most crimes has surely expired after 33 years.

The law doesn’t work that way for people like us, Benjamin replied, exchanging a knowing glance with grace.

There is no statute of limitations for a black man accused of killing a white master, especially in Maryland.

And a plantation owner’s journal wouldn’t outweigh three decades of accepted history.

Isaiah, now 32 and married with two children of his own, supported his father’s caution.

We have good lives here.

Our children are Canadian, born free, and raised without the shadow of American slavery.

Why risk that? Ruth remained quiet during these discussions, though Benjamin noticed her watchful eyes moving between her brothers and her parents, absorbing every word.

Of the three children, she was the one who most resembled grace in temperament, observant, thoughtful, and rarely revealing her full thoughts until she had considered all angles of a situation.

It was Ruth who eventually proposed a compromise.

Father shouldn’t return,” she said one evening, breaking her silence on the matter.

“The risk is too great, regardless of how much time has passed, or what evidence exists of his innocence.

But perhaps one of us could go in his place, not to live, but to visit the places that were important in your story, to see what remains of the Caldwell plantation, to perhaps even locate some record of what happened to Ruth Brooks after you escaped.

The suggestion resonated with Benjamin in a way he hadn’t anticipated.

Though he had long ago accepted that he would never again set foot in the United States, the idea that one of his children might visit on his behalf might see the land where he had been enslaved and from which he had fled touched something deep within him.

“I would go,” James offered immediately.

I’ve studied American law enough to navigate safely, and I look enough like father that I could see it through his eyes.

The plan took shape gradually over the following months.

James would travel to Maryland in the summer of 1868, ostensibly as a Canadian law student, researching the legal aftermath of American slavery.

He would visit Tolbert County, where the Caldwell plantation had been located, and attempt to discover what had happened to the people Benjamin and Grace had left behind, particularly Ruth Brooks, whose fate remained unknown.

Benjamin spent hours with James before his departure, describing the geography of the eastern shore, the layout of the Caldwell plantation, the locations of nearby towns and waterways that had featured in their escape.

He drew maps from memory, marking the path they had taken that night in 1834, the location of the slave quarters where Isaiah and Ruth Brooks had lived, the spot behind the tobacco barn where the fatal struggle with William Caldwell had occurred.

Be careful, Benjamin warned his son repeatedly.

No matter what you discover, remember that you’re there as an observer, not to write old wrongs.

Your mother and I have made our peace with the past.

James departed for the United States in June of 1868, promising to write whenever possible and to return within two months.

The weeks of his absence were difficult for Benjamin and Grace, who found themselves revisiting memories and emotions they had long ago set aside.

They attended to their daily tasks with their usual diligence, but their thoughts were often with their youngest son as he traveled through the landscape of their former captivity.

The first letter from James arrived after 3 weeks posted from Baltimore.

He wrote of his journey south from New York, of his first impressions of the city where Benjamin and Grace had begun their journey to freedom, and of his meetings with members of the local free black community.

He had connected with abolitionists who had known Rachel, though the elderly Quaker herself had passed away the previous winter.

Through these contacts, he had arranged transportation to Talbert County and gained introductions to people who might help in his research.

The second letter, arriving two weeks later, contained more significant news.

James had visited what had once been the Caldwell Plantation, now divided into smaller parcels following the war.

The main house still stood, though it had been damaged during the conflict and subsequently repaired by its new owner, a northern businessman who had purchased the property at auction.

James had introduced himself as a Canadian researcher interested in the history of the region and had been permitted to tour the grounds.

I stood in the very places you described, father, he wrote.

The oakline drive, the cleared fields where tobacco once grew, the foundations of the slave quarters that were dismantled after the war.

I found the spot behind what remains of the tobacco barn where Caldwell confronted you and mother.

A wild rose bush grows there now, its thorns and blossoms marking the place where your life changed forever.

James had also made inquiries about Ruth Brooks and discovered to Benjamin and Grace’s great relief that she had survived.

After Isaiah’s death from the whipping, Ruth had been sold to a plantation in Virginia, where she remained until emancipation.

According to local records, she had returned to Tolbert County after the war.

one of many freed people who sought to reconnect with places and people from their past.

She had lived her final years in a small community of former slaves near the town of Easton, passing away in 1866 at approximately 70 years of age.

The people I spoke with remember her as a storyteller, James wrote.

She would gather children around her and tell them about the old days, about the people she had known who escaped to freedom.

She spoke often of a couple who fled north after a confrontation with their master, describing how they had gone on to build new lives beyond the reach of slavery.

I believe she was telling your story, father, keeping your memory alive while protecting your identities.

The third and final letter arrived shortly before James himself returned to Montreal.

In it, he described his most significant discovery, a small collection of documents in the courthouse at Eastston that included depositions taken in the days following William Caldwell’s death.

Among these papers was a statement from James Rutlage that had never been made public in which he described the events of that morning in terms that largely matched Benjamin’s account of the accidental shooting during a struggle.

The deposition was filed but apparently ignored.

James wrote, “The narrative of a deliberate murder had already taken hold, fueled by the fears of other plantation owners who saw in Caldwell’s death a threat to their own authority.

” Ratledge’s statement was inconvenient to this narrative, and so was quietly set aside, though never destroyed.

“I’ve made a copy, which I’ll bring home with me.

” When James returned to Montreal in August, the family gathered to hear his full account of the journey.

He brought with him the copied deposition, several sketches he had made of the former Caldwell plantation, and a small cloth pouch that he presented to his father with particular somnity.

“This belongs to you,” he said, placing it in Benjamin’s hands.

Inside the pouch was a smooth black stone approximately the size of a man’s thumb.

Benjamin stared at it in confusion before understanding dawned in his eyes.

Ruth Brooks gave this to me the night before we left,” he explained to his children.

“She said it had been passed down through generations of her family, brought from Africa by her great grandmother.

She told me it would protect us on our journey.

” His voice broke as he added, “I always regretted that I had nothing to give her in return.

The woman who told me about Ruth had this in her possession, James explained.

She said Ruth had given it to her daughter before she died, telling her it was meant to travel north someday to follow the path of those who had escaped.

When I explained my connection to the story, she insisted I bring it to you.

” Benjamin closed his fingers around the stone, feeling its weight and warmth.

This small object had completed a journey that had begun 34 years earlier, passing through hands that connected him to the community he had left behind, to the people who had suffered because of his flight to freedom.

There was something profound in its return, something that spoke to the resilience of bonds that slavery had tried but failed to sever.

The years continued their steady progression.

Benjamin and Grace grew older, their hair turning white, their steps slowing, but their minds remaining sharp.

Their print shop became a gathering place for Montreal’s black community, a space where ideas were exchanged, where newspapers from across Canada and the United States were read and discussed, where the ongoing struggle for equality was debated with passion and insight.

In 1876, as the United States celebrated its centennial, Benjamin fell ill with pneumonia.

The illness struck suddenly and progressed rapidly, leaving him bedridden and struggling for breath despite the best efforts of doctors.

Grace rarely left his side during those difficult days, nor did their children, who took turns reading to him from his favorite books when he was too weak to hold them himself.

On a cold evening in February, with snow falling gently outside the bedroom window, Benjamin asked to speak with each of his children privately.

To Isaiah, his firstborn, he entrusted the print shop, and the responsibility of continuing its tradition as a place of learning and discussion.

To Ruth, he gave his collection of books, many of which he had printed himself over the years.

To James, he gave the metal box containing the documents of their journey, including Wilson’s letter about Rutled’s confession and the copy of the deposition that James himself had discovered in Easton.

“These papers tell our story,” he told his youngest son.

“Not just mine and your mothers, but the larger story of what slavery was and what freedom could be.

Keep them safe, but also share them when the time is right.

” The world needs to remember.

When the children had gone, leaving only Grace at his bedside, Benjamin reached for her hand.

“Do you remember what you said to me when we learned about Caldwell’s journal?” he asked, his voice barely above a whisper.

Grace nodded, tears filling her eyes.

“I said his death gave life to all of this, to our children, to our home, to everything we built together.

I’ve thought about that often over the years, Benjamin said about how something so terrible could lead to something so precious.

I never wanted to be the cause of any man’s death, even a man like Caldwell.

But I cannot regret the life that came after.

Nor should you, Grace replied firmly.

You defended us both that morning.

Everything that followed, every struggle, every joy, every moment of our life together grew from that single act of courage.

Benjamin smiled weakly, his eyes drifting to the window where snowflakes swirled against the darkening sky.

“We’ve come so far from that morning behind the tobacco barn.

” “Yes,” Grace agreed softly.

And yet sometimes it feels as though no time has passed at all.

As though we’re still those young people, terrified but determined, stepping into an unknown future.

I wouldn’t change it, Benjamin murmured as his eyes began to close.

Not one day of it.

He slipped away peacefully in the early hours of the morning, Grace still holding his hand as his breathing gradually slowed and then stopped altogether.

The man who had been born into slavery as Samuel Green, who had fled north as a fugitive accused of murder, who had built a new life as Benjamin Freeman was gone.

But the legacy he left behind endured in his children, his grandchildren, and in the story of courage and perseverance that would be passed down through generations to come.

Grace lived another 5 years after Benjamin’s death, continuing to share their story with her grandchildren, ensuring that they understood the price that had been paid for the freedom they enjoyed.

She spoke of the accident that had claimed William Caldwell’s life, not with shame or regret, but as a moment when fate had intervened to set them on a path toward liberty, a difficult path filled with danger and sacrifice, but one that had ultimately led to redemption.

When she died in 1881, she was buried beside Benjamin in a small cemetery on the outskirts of Montreal.

Their gravestone, a simple marker of polished granite, bore only their chosen names, Benjamin and Grace Freeman, and the dates of their birth and death.

But their children knew the full story, as did their grandchildren, and in time their great grandchildren.

The black stone that had traveled from Africa to Maryland to Montreal was passed down through the family, a tangible connection to their history.

So too were the documents Benjamin had preserved.

The letters, the journal entries, the deposition that corroborated his account of William Caldwell’s death.

These items became touchstones for subsequent generations, reminders of where they had come from and the courage it had taken to forge a path to freedom.

In 1934, exactly 100 years after Samuel Green and Martha Turner fled the Caldwell Plantation, their greatgrandson, David Freeman, a professor of history at a university in Toronto, compiled their story into a manuscript.

Drawing on family documents and additional research conducted in archives throughout the United States and Canada, he created the most complete account to date of the events surrounding William Caldwell’s death and the subsequent escape of the two people he had enslaved.

The manuscript was never published during David’s lifetime, partly due to concerns about how the story would be received in an era when racial prejudices remained deeply entrenched, and partly because he viewed it primarily as a family history rather than a public document.

But he ensured that copies were made for each branch of the family, preserving the narrative for future generations.

It was not until 1968 as the civil rights movement reshaped American society and prompted a re-evaluation of historical narratives about slavery and its aftermath that David’s daughter Eleanor considered publishing her grandfather’s manuscript.

By then the story was more than a century old and most of the direct participants had been dead for decades.

The statute of limitations on any crime related to William Caldwell’s death had long since expired, and the political and social landscape had changed dramatically.

Eleanor, a journalist by profession, revised and expanded her father’s manuscript, conducting additional research in Maryland, where records that had once been inaccessible were now available for scholarly review.

What she discovered in these archives largely confirmed the account that had been passed down through her family, the accidental nature of Caldwell’s death, the fabricated conspiracy that had been constructed afterward, the deliberate suppression of evidence that might have contradicted the official narrative.

When Elellanar finally published the Freeman Legacy in 1972, it was received with significant interest by historians studying the Antibbellum South and the Underground Railroad.

The documented journey of Samuel Green and Martha Turner, later Benjamin and Grace Freeman, provided a detailed case study of how enslaved people navigated the dangerous path to freedom, and how the institutions of slavery worked to control not only their bodies, but the narratives surrounding their resistance.

Some descendants of the Caldwell family initially contested the book’s portrayal of their ancestor, but the documentary evidence Elellaner had assembled, including William Caldwell’s own journal entries and James Rutled’s suppressed deposition, ultimately proved persuasive.

In a gesture of reconciliation that received national attention, representatives of the Caldwell and Freeman families met in 1975 at the site of the former plantation to acknowledge their shared history and the tragedy that had connected their lineages.

A small memorial was erected near the spot where the fatal struggle had occurred, bearing an inscription that read, “On this ground in 1834, a confrontation born of the injustice of slavery led to an accidental death and a desperate flight toward freedom.

May the truth of what happened here remind us of our common humanity and our ongoing responsibility to uphold the dignity of every human life.

The black stone that had passed from Ruth Brooks to Benjamin Freeman and through subsequent generations of his family was placed in a small niche within the memorial symbolically completing its journey from Africa to America to Canada and back again.

a descendant of Ruth Brooks, located through Elellanena’s research, participated in the ceremony, bringing the intertwined stories of these families full circle after more than a century.

Today, visitors to Tolbert County, Maryland, can still see this memorial, now part of a historical park that includes remnants of the original Caldwell Plantation and exhibits detailing the history of slavery on Maryland’s Eastern Shore.

The story of Samuel Green and Martha Turner, of their transformation into Benjamin and Grace Freeman, and of the accidental death that precipitated their flight to freedom, serves as a powerful reminder of the complex and often tragic ways in which the institution of slavery shaped individual lives and continues to influence our understanding of American history.

The sound that still echoes from that fateful morning in 1834 is not just the report of a shotgun discharged in struggle, but the enduring call for justice, dignity, and recognition of our shared humanity that resonates across generations.

It reminds us that history is never as simple as the stories we tell about it.

that beneath the official narratives lie countless individual experiences of resistance, resilience, and the unwavering pursuit of freedom against overwhelming odds.

As Benjamin Freeman himself observed in the final days of his life, something terrible gave rise to something precious, a paradox that perhaps encapsulates the broader American experience with its painful contradictions and its ongoing struggle to fulfill the promise of liberty for all its people.

The legacy of that struggle continues to this day.

A testament to the courage of those who, like Samuel Green and Martha Turner, refused to accept the boundaries that others had placed upon their lives and dared to imagine a different future for themselves and for generations yet unborn.

News

✈️ U.S. F-15 FIRST STRIKE — ALLEGED CARTEL DRUG LAB ERASED IN SECONDS AS SKY ERUPTS IN A BLINDING FLASH ✈️ What officials described as a precision operation turned the night into daylight, with jets screaming overhead and a suspected production site reduced to smoking rubble in moments, sending a shockwave across the region and a message that the airspace above is no safe haven for hidden empires 👇

The Last Fortress: A Shocking Revelation In the heart of the Mexican jungle, Diego stood at the entrance of the…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: FBI & ICE SHATTER ALLEGED TRUCKING NETWORK WITH SOMALI TIES — 83 ARRESTED, $85M IN CASH AND WEAPONS STACKED AS EVIDENCE 🚨 Before sunrise, federal agents swept through depots and dispatch offices, hauling out duffel bags of currency and seizing firearms while stunned neighbors watched a logistics operation authorities claim was hiding a sprawling criminal enterprise behind everyday freight routes 👇

The Shadows of the Ghost Fleet In the heart of the Midwest, where the snow fell like a blanket over…

🚨 FBI & ICE STORM GEORGIA “CARTEL HIDEOUT” — GRENADE LAUNCHER DISCOVERED AND $900K IN DRUGS SEIZED IN A DAWN RAID THAT SHOCKED THE BLOCK 🚨 What neighbors thought was just another quiet morning exploded into flashing lights and tactical vests as agents swept the property, hauling out weapons and evidence while officials described a months-long investigation that culminated in a swift, coordinated takedown 👇

The Unraveling of Shadows: A Tale of Betrayal and Redemption In the heart of Jackson County, Georgia, the air was…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: DEA & FBI CRUSH ALLEGED CARTEL TRUCKING EMPIRE — HIDDEN ROUTES MAPPED, DRIVERS DETAINED, AND MILLIONS STACKED AS EVIDENCE 🚨 Before sunrise, highways turned into a grid of flashing lights as agents intercepted rigs, cracked open trailers, and traced coded dispatch logs, revealing what officials describe as a logistics web hiding in plain sight behind ordinary freight lanes 👇

The Fall of Shadows: A Cartel’s Empire Exposed In the dimly lit corridors of power, where shadows danced with deceit,…

🚢 U.S. NAVY TRAPS SINALOA CARTEL’S ALLEGED $473 MILLION “DRUG ARMADA” AT SEA — AND THE HIGH-STAKES STANDOFF UNFOLDS UNDER FLOODLIGHTS AND ROTOR WASH 🚢 Radar screens lit up, cutters boxed in fast boats, and boarding teams moved with clockwork precision as authorities described a sweeping maritime interdiction that turned open water into a chessboard, stacking seized cargo on deck while prosecutors hinted the ripples would travel far beyond the horizon 👇

The Abyss of Deceit: A Naval Reckoning In the heart of the Caribbean, where the turquoise waters glimmered under the…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: DEA & FBI DESCEND ON MASSIVE TEXAS LOGISTICS HUB — 52 TONS OF METH SEIZED AS 20 POLITICIANS ALLEGEDLY TIED TO A SHADOW NETWORK ARE THRUST INTO THE SPOTLIGHT 🚨 What began as a quiet federal probe detonated into a sweeping raid of warehouses and boardrooms, with agents hauling out towering stacks of evidence while stunned insiders whisper that the real shockwave isn’t just the drugs — it’s the powerful names now facing intense scrutiny 👇

Shadows of the Underground: The Texas Cartel Unveiled In the heart of Texas, where the sun sets over sprawling landscapes,…

End of content

No more pages to load