The Plantation Owner Gave His Son Five Beautiful Slaves.

What They Did Next Left Everyone Shocked

Welcome to one of the most disturbing cases recorded in the history of Savannah, Georgia.

Before we begin, I invite you to leave in the comments where you’re watching from and the exact time you’re listening to this narration.

We’re interested to know how far and at what times of day or night these documented accounts reach.

The year was 1843, and Savannah stood as one of the wealthiest port cities in the American South.

The grand oak trees draped with Spanish moss cast long shadows across the cobblestone streets, while behind the pristine facads of the stately mansions along Foresight Park lay secrets that few dared to whisper.

Among these mansions stood Magnolia Heights, the ancestral home of the Langford family, situated approximately 3 mi north of the city center, surrounded by acres of cotton fields that stretched toward the Savannah River.

On May 7th, 1843, according to county records still preserved in the Chattam County archives, James Langford, a prominent plantation owner, summoned his son, Robert, to the main house.

What transpired that day would set in motion a chain of events that would shatter the illusion of gental southern life and expose the brutal realities that existed beneath the surface.

Present at this meeting was also James’s business partner, William Harrison, whose written account, discovered decades later in 1867, provides one of the few firstirhand descriptions of the encounter.

According to Harrison’s journal found during renovations of the old Harrison estate on Bull Street in 1867, James Langford had been diagnosed with consumption.

The physician had given him less than 6 months to live.

His son, Robert, who had recently returned from studying at Harvard College in Massachusetts, was to assume control of the family’s vast holdings.

As was customary for wealthy planters at the time, James intended to bestow upon his son a gift to mark his transition into the role of master.

Harrison wrote, “James called forth five individuals from among his human property, each selected for their skills and intelligence, and pronounced them henceforth under Robert’s direct ownership.

” The young master’s face betrayed neither pleasure nor dismay, but something else entirely, a look I found myself unable to decipher.

The individuals in question were documented in the Langford Plantation ledger as Samuel, aged 28, a skilled carpenter.

Martha, aged 24, trained in household management.

Isaiah, aged 31, knowledgeable in agricultural methods.

Elizabeth, aged 26, experienced in textile production.

and Thomas, aged 33, literate and trained in bookkeeping, a rare and valuable skill that was often illegally bestowed.

Each was listed with a monetary value that exceeded $1,000, marking them as premium property in the grotesque economy of human bondage.

What Harrison’s journal did not record, but what subsequent investigations would reveal was that these five individuals shared another common trait.

They were all literate, having been secretly taught to read and write by Elizabeth Stanford, the deceased wife of James Langford and Robert’s mother, who had died 7 years earlier.

The events that unfolded after this transfer of ownership were pieced together decades later through fragments of evidence, letters hidden between floorboards, coded messages sewn into quilt patterns, and verbal accounts passed down through generations of Savannah’s African-Amean community.

Each fragment revealed a portion of a truth that Savannah society had desperately attempted to bury.

Robert Langford was not like his father, nor like most sons of plantation owners.

His years in Massachusetts had exposed him to abolitionist thought, and while he had kept his evolving views private during his visits home, his return as heir to Magnolia Heights placed him in an impossible moral position.

According to a letter discovered in 1958 during the restoration of a historic home on Harbasham Street written by Robert to a former classmate named Edward Bennett.

He described his predicament.

To reject my father’s gift would expose my true sentiments and place these souls in greater peril.

To accept is to become complicit in an institution I have come to recognize as humanity’s greatest sin.

The summer of 1843 was recorded as unusually hot and humid even by savannah standards.

The ledges of Magnolia Heights preserved in the Georgia Historical Society archives showed a decline in cotton production during this period.

Neighboring plantation owners attributed this to Robert Langford’s soft management and northern ideas.

What these ledgers did not show, but what oral histories collected by researcher Margaret Wilson in 1962 would later reveal was that behind the facade of declining productivity, something unprecedented was taking shape.

Robert Langford had indeed accepted his father’s gift, but not in the manner intended.

According to accounts attributed to Hannah Green, a washerwoman whose grandmother had worked at Magnolia Heights, Robert met secretly with the five individuals in the old carriage house behind the main mansion.

There, in hushed tones beneath the creaking wooden beams, he acknowledged their humanity and proposed a dangerous idea, one that would either lead to their freedom or their destruction.

The plan, as pieced together by historians, involved the creation of a ruse, a fiction that would allow Robert to manummit the five individuals without arousing the suspicion and wrath of Savannah society.

The city’s archives contain a curious document dated July 12th, 1843.

A report of theft at Magnolia Heights alleging that the five individuals had stolen money, valuables, and documents before fleeing north.

What actually occurred, according to a letter found concealed in a hollow book discovered during the 1964 demolition of a building on Broton Street, was an elaborate deception.

Robert had provided funds, forged papers, and a carefully planned escape route that would take Samuel, Martha, Isaiah, Elizabeth, and Thomas North along the Underground Railroad.

The deception might have succeeded had it not been for an unexpected complication.

James Langford, contrary to his physician’s prognosis, experienced a temporary improvement in his condition.

On July 15th, he made an unannounced visit to the quarters where the five individuals had been housed.

Finding them empty, he immediately ordered a search of the property.

The Savannah Republican newspaper in its July 17th edition reported that Mr.

James Langford offers a substantial reward for information leading to the recovery of five valuable negroes who have absconded from his plantation.

The notice included detailed descriptions of each individual and the warning that they might be carrying forged freedom papers.

What the newspaper did not report was the confrontation that occurred between father and son.

According to the diary of Sarah Harrison, William Harrison’s wife, which was discovered in a trunk in the attic of their former home in 1959, James Langford had flown into a rage upon discovering his son’s betrayal.

William returned from Magnolia Heights ashenfaced, she wrote.

He spoke of shouting that could be heard from the study of accusations of theft and betrayal and most disturbing of threats that would destroy the family name.

The records of the Savannah Police Department, partially preserved despite a fire in 1895, contain a curious entry dated July 19th, 1843.

A patrol was dispatched to Magnolia Heights following reports of a disturbance.

Upon arrival, they were turned away by James Langford, who insisted all was well.

However, a separate entry in the medical examiner’s log book noted that James Langford requested a physician that same evening.

The next series of events created ripples of unease throughout Savannah society.

On July 21st, James Langford announced that the stolen property had been recovered, but mysteriously no one outside the plantation was permitted to see the five individuals in question.

Simultaneously, Robert Langford disappeared from public view.

Rumors circulated that he had fallen ill, though no physician acknowledged being called to attend him.

The truth, as revealed in fragments of a journal discovered behind a loose brick in the cellar of Magnolia Heights during renovations in 1957, was far more disturbing.

The journal, believed to have belonged to Thomas, the bookkeeper, suggested that upon learning of the escape plan, James Langford had imprisoned his son in a storage room beneath the main house, a space once used to discipline enslaved people who had attempted escape.

From this point forward, the documented history becomes increasingly fractured.

Plantation records indicate that cotton production resumed its normal pace by August.

The five individuals appeared in subsequent inventory records.

Robert Langford was reported to have departed for an extended tour of Europe, though no passenger manifests from Savannah’s port could confirm his departure.

A disturbing clue emerged in a letter sent from a Mrs.

Elellanena Whitfield of Charleston to her cousin in Savannah dated September 3rd, 1843.

I was most disturbed by my recent visit to Magnolia Heights.

Though James assured me his son was abroad, I could not shake the feeling of being watched from the upper windows of the east wing, where the curtains remained drawn despite the stifling heat.

More unsettling still was the demeanor of the house servants, who moved about their duties with a strange, almost mechanical precision, their eyes downcast, but seemingly alert to every word spoken.

The autumn of 1843 brought the annual harvesting season, and with it increased activity at Magnolia Heights.

County records indicate that James Langford hired additional overseers during this period, an unusual expense for a plantation that had not increased its acreage or number of enslaved workers.

These overseers, according to tax records, were housed not in the usual quarters, but in a newly constructed building adjacent to the main house.

A letter from James Langford to his banker preserved in the archives of the Merchants Bank of Savannah requested a substantial withdrawal of funds on October 12th for security measures necessitated by recent events.

No elaboration was provided, but the banker noted in his personal journal discovered during a 1961 inventory of the bank’s historical documents that Mr.

Langford appeared greatly altered since last we met, thinner certainly due to his condition, but changed in manner also.

His once commanding presence now seemed tinged with something akin to fear.

The first concrete evidence that something truly alarming had occurred at Magnolia Heights came in the form of an anonymous letter sent to the mayor of Savannah in November 1843.

The letter preserved in the city archives reported strange sounds emanating from Magnolia Heights in the dead of night.

Not the usual sounds of a working plantation, but cries that seem neither fully human nor animal, and lights moving among the cotton fields when no work should be underway.

The mayor, as recorded in council minutes, dismissed the letter as the fantastic imaginings of an unsound mind or the malicious attempt of a competitor to sully the Langford name.

No.

Investigation was ordered.

As winter descended upon Savannah, bringing with it an unusual chill, activity at Magnolia Heights seemed to diminish.

Deliveries from town were received at the gate rather than the main house.

James Langford was rarely seen in public.

His declining health cited as the reason.

The five individuals who had allegedly attempted escape were not seen at all, though neighboring plantation owners reported that work continued in the fields and household.

December brought the annual Christmas ball, an event at which the Langford family had traditionally played a prominent role.

James Langford sent his regrets, again citing ill health.

However, a curious note in the diary of Josephine Parker, wife of a neighboring plantation owner, indicated that on the night of the ball, multiple lanterns could be seen moving across the grounds of Magnolia Heights, in a pattern that suggested a search was underway.

The new year of 1844 began with a series of unusual incidents.

Three enslaved individuals from neighboring plantations disappeared, only to return days later, disoriented and unable or unwilling to explain their absence.

Each bore similar marks on their wrists, as if they had been restrained.

None would speak of what had happened, but all requested reassignment to tasks that would keep them far from the boundaries shared with Magnolia Heights.

February brought news that shocked Savannah society.

James Langford had died, not from the consumption that had plagued him, but from what the death certificate vaguely described as misadventure.

The Savannah Republicans obituary, while respectful of the prominent family, noted that the circumstances surrounding Mister Langford’s passing remain unclear, though sources close to the family suggest a tragic accident occurred while he was inspecting the property.

The funeral was closed to all but immediate family, of which there were few.

Robert Langford, still allegedly in Europe, was not present.

The five individuals given to him by his father were not visible among the household staff who attended.

William Harrison, James Langford’s longtime business partner, was noted by several attendees to be visibly distressed, not merely with grief, but with what one observer described as a terror barely contained.

In the weeks following the funeral, Magnolia Heights fell silent.

The gates remained closed to visitors.

Supplies were delivered and left at the entrance.

The overseer hired the previous autumn departed abruptly, telling neighbors he had secured a position in Augusta that could not wait.

The true nature of what had transpired behind the gates of Magnolia Heights might have remained forever hidden had it not been for a fire that broke out in the east wing of the mansion on March 15th, 1844.

According to the fire captain’s report, preserved despite attempts to have it expuned from official records, the east wing had been converted into what he described as a place of confinement with rooms secured by heavy locks and windows barred from the outside.

Most disturbing was his description of what appeared to be a medical facility containing instruments of a surgical nature, substances in glass vials, and extensive written records documenting what can only be described as experimentation.

The names Samuel, Martha, Isaiah, Elizabeth, and Thomas appeared repeatedly in these records along with detailed observations of responses to stimuli and modifications of behavior.

The records also contained references to the subject RL and continuing refinements to ensure compliance.

The fire brigade’s discovery prompted immediate action from city officials who arrived at Magnolia Heights to find the plantation largely deserted.

The fire brigade from Savannah responded and in the course of battling the blaze made a discovery that would haunt the city for generations.

No trace was found of Robert Langford or the five individuals named in James Langford’s records.

The only person present was an elderly man who had served as gardener for decades who claimed to have been away visiting family when the fire broke out.

When questioned about the activities in the east wing, he crossed himself and refused to speak further.

A subsequent investigation conducted quietly to avoid scandal uncovered a hidden chamber beneath the main house, accessible through a concealed entrance in the library.

Within this chamber, investigators found evidence that someone had been held there for an extended period, perhaps months.

Scratched into one wall were five names: Samuel, Martha, Isaiah, Elizabeth, and Thomas.

Below them was carved a single phrase, “We tried.

” The investigation was abruptly halted by order of the governor who cited concerns for public order and the reputation of a distinguished family.

The east wing was demolished, the records confiscated, and a cover story circulated that blamed the fire on a lightning strike.

For almost a decade, Magnolia Heights remained abandoned, its fields untended, its buildings slowly reclaimed by nature.

In 1853, the property was purchased by a northern industrialist who had no knowledge of its history.

The main house was renovated, the outbuildings demolished, and a new chapter began.

Yet stories persisted among the people of Savannah.

Stories of light seen moving across the former plantation grounds on certain nights, of voices carried on the wind when no one was present, of five figures sometimes glimpsed at dawn before disappearing into the morning mist.

The true fate of Robert Langford and the five individuals remained unknown until 1869 when a package arrived at the offices of the Liberator, an abolitionist newspaper in Boston that had continued publishing after the Civil War.

The package contained a journal, its pages weathered and stained, along with five handcarved wooden figures.

The journal, authenticated as belonging to Thomas, the literate bookkeeper, revealed the horrifying truth.

James Langford, upon discovering his son’s plan to help the five individuals escape, had implemented a contingency plan of his own, one born from his knowledge of experimental medical procedures and his determination to maintain control even after his death.

Thomas wrote, “He has done something to Master Robert.

The young master speaks and moves, but his eyes are empty.

The words from his mouth are not his own.

We try to reach him to remind him of his promise, but he looks through us now.

Yesterday he watched without expression, as his father demonstrated what would happen should we attempt escape again.

Isaiah’s screams still echo in my ears.

” The journal detailed how James Langford, faced with his own mortality, had sought to ensure his legacy and maintain control of his property through experimental procedures performed on his son and the five individuals.

Using techniques he had learned from a European physician with whom he had corresponded for years, James had attempted to break and rebuild their wills to create what Thomas described as vessels empty of themselves, but filled with his purpose.

The experiments had ultimately failed, or perhaps succeeded in ways James had not anticipated.

According to Thomas’s final entries, the five individuals, despite the procedures performed on them, had retained enough of their own consciousness to formulate a plan, working together over months, communicating through signals developed during their captivity.

They had gradually altered the chemical substances James administered to his son.

The altered substances had affected James instead when Robert, in one of his moments of lucidity, had ensured his father received a concentrated dose.

The accident that had claimed James Langford’s life had been engineered by his victims.

In the chaos following James’ death, the five individuals had managed to escape, taking the semic-conscious Robert with them.

Thomas’s journal chronicled their journey north along the Underground Railroad, the gradual recovery of Robert’s mind, and their eventual arrival in Canada.

The final pages of the journal contained a letter written in Robert’s hand, but signed by all six individuals, addressed to future generations.

Let our story stand as testament to the darkest capacities of the human soul when it denies the humanity of others and to the enduring power of that humanity to prevail.

We six once master and owned now move forward as equals bearing scars visible and invisible but determined that the horrors we endured shall not be the end of our story.

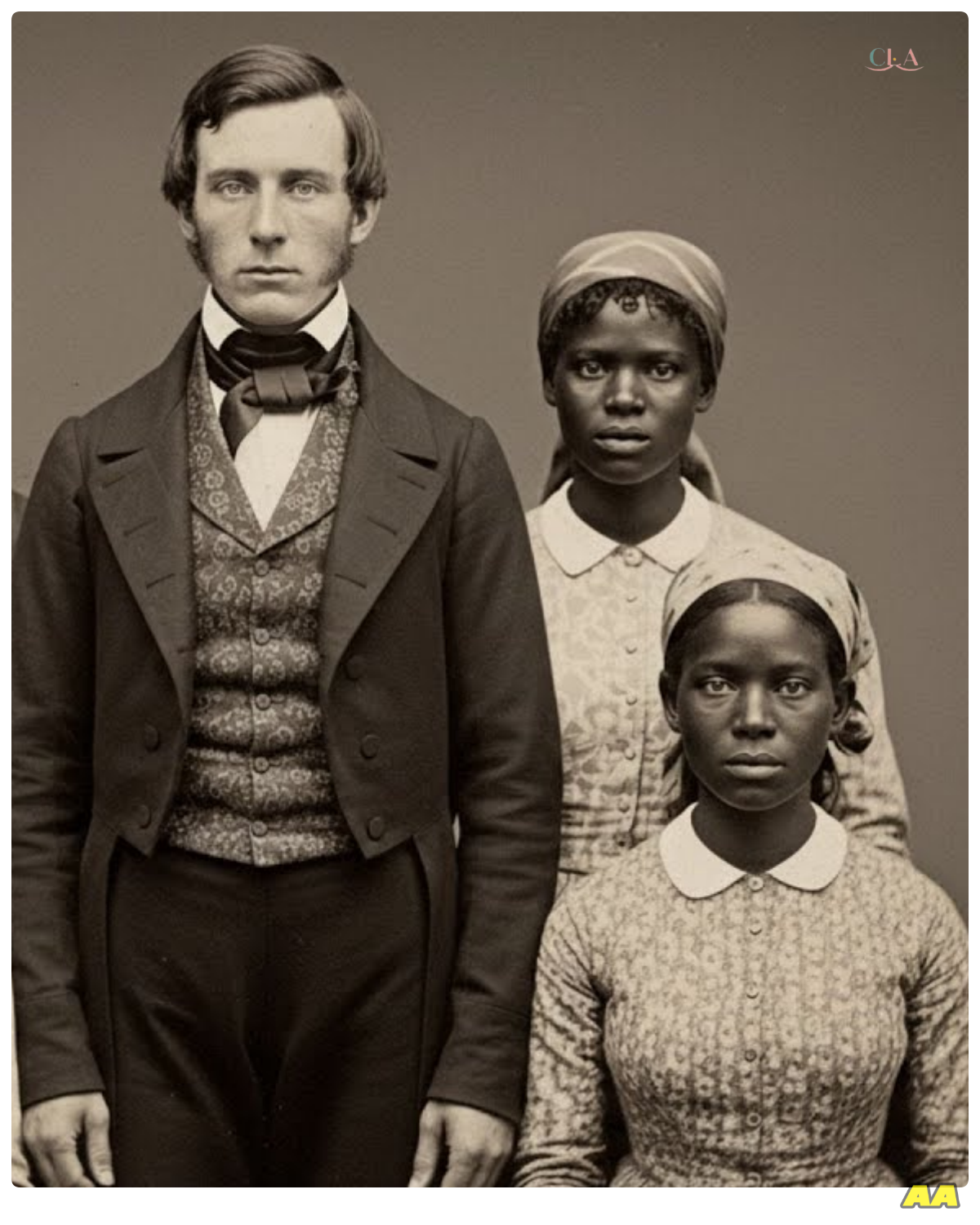

The package sent to the liberator included a dgera type showing six individuals standing together before a small farmhouse.

Their faces solemn but their posture suggesting a hard one dignity.

On the back was written free in body and mind.

Ontario 1868.

The wooden figures included in the package were eventually donated to the Smithsonian Institution where they remained in storage until 1959 when a researcher recognized their significance.

Carved from magnolia wood, each figure depicted one of the six survivors of Magnolia Heights.

X-ray examination revealed that each contained a small compartment holding a folded paper with a name, a symbolic reclaiming of identities once reduced to property.

Today, the land where Magnolia Heights once stood has been developed into a residential neighborhood.

Few of the current residents know the history beneath their homes.

The documents that revealed the story remained scattered in archives until 1965 when historian Elellanena Marshall assembled them for a doctoral dissertation that was ultimately published only in a limited academic edition.

Its contents deemed too disturbing for general release.

Yet the story remains preserved in fragments across multiple collections.

a testament to the horrors of a system that commodified human beings and the resistance that system inevitably provoked.

The full truth of what occurred at Magnolia Heights, the exact nature of James Langford’s experiments, the details of the six survivors escape and journey may never be completely known.

What is certain is that in 1843, a father gave his son five human beings as property, and by 1868, six people stood together as equals, having survived and overcome horrors designed to strip them of their humanity.

Their story serves as both warning and affirmation, a reminder of the darkest chapters of American history and of the inextinguishable light of human dignity that no system of oppression, however brutal, has managed to permanently extinguish.

In 1968, exactly 100 years after the Dgera type was taken, a descendant of Thomas visited the site where Magnolia Heights once stood.

According to local newspaper accounts, she carried with her six candles, which she lit at dawn before departing.

A resident who witnessed this act later reported that as the morning light strengthened, they could almost discern six figures standing among the trees, watching as the candles burned down to nothing.

To this day, some residents report hearing voices on certain nights.

Not cries of pain, but something like singing, soft and determined, moving across the land where cotton once grew under the overseer’s lash, and where six people once forged an unlikely alliance that carried them from bondage to freedom.

Visitors to the area sometimes report a strange sensation, a momentary disorientation, as if time has slipped, followed by an overwhelming urge to examine their own lives for places where they may have denied the humanity of others.

Local historians attribute this to the power of suggestion, but those who have experienced it describe it as something more, a lingering echo of a truth that refuses to be silenced.

In the words carved into that hidden chamber so many years ago, we tried.

And in trying, in refusing to surrender their essential humanity despite unimaginable pressure to do so, Samuel, Martha, Isaiah, Elizabeth, Thomas, and Robert left a legacy more enduring than any plantation mansion.

They remind us that even in the darkest circumstances, the human spirit retains the capacity for resistance, for compassion, and ultimately for transformation.

Their story is not merely a historical curiosity or a ghostly legend.

It stands as a moral challenge across time, asking each of us how we recognize and honor the humanity in others, how we respond to systems that deny that humanity, and whether we have the courage to stand against such systems, even at great personal cost.

The true horror of Magnolia Heights was not supernatural, but entirely human.

the horror of one person claiming ownership of another, of viewing fellow humans as property rather than as bearers of inherent dignity and worth.

And the true light that emerged from that darkness was also entirely human.

The light of resistance, of solidarity across artificially imposed boundaries, and of the recognition that freedom must be for all if it is to be meaningful for any.

As we close this account, we invite you to consider not only the specific history of these six individuals, but the broader implications of their story.

The cotton harvested at Magnolia Heights was processed into textiles that clothed people across America and Europe.

People who may never have seen a plantation or an enslaved person, yet whose comfort and prosperity were built upon a foundation of human suffering.

The ripples of systems like slavery extend far beyond their immediate context, implicating all who benefit, however indirectly or unknowingly.

Perhaps the most powerful legacy of Samuel, Martha, Isaiah, Elizabeth, Thomas, and Robert is the reminder that our humanity is not diminished when we recognize and honor the humanity of others.

It is enlarged and enriched.

Their journey from property and owner to a community of equals stands as a beacon, illuminating not just a dark chapter of history, but a path forward toward a more just and humane world.

The next time you walk a street in Savannah or any city built on forgotten histories of exploitation and resistance, listen carefully.

Beyond the tourist attractions and the carefully preserved facads of historic buildings, other stories wait to be heard.

Stories that may disturb our comfortable narratives, but that offer deeper truths if we have the courage to hear them.

The six candles lit on that dawn in 1968 have long since burned away.

But the light they symbolized continues to burn, challenging each new generation to examine the past honestly and to build a future worthy of those who refused to surrender their humanity even when all worldly power was arrayed against them.

In 1959, a collection of letters was discovered during the renovation of a small church in Ontario, Canada.

These letters, written between 1871 and 1893, provided further insight into the lives of the six survivors after their escape.

According to these documents, they had established a small but thriving farm community, eventually joined by other formerly enslaved people who had made the perilous journey north.

What made these letters particularly remarkable was their correspondence with several prominent abolitionists and early civil rights advocates, including Frederick Douglas and Sojon Truth.

One letter dated March 15th, 1874.

exactly 30 years after the fire at Magnolia Heights revealed that Robert Langford had formally transferred all remaining Langford assets to a trust established for the benefit of individuals formerly enslaved by his family.

The legal document executed through intermediaries to protect the identities and location of the six included a public confession and repudiation of his family’s role in the institution of slavery.

Perhaps most poignant among the discovered letters was one written by Elizabeth to a woman named Claraara Williams who had been enslaved at a neighboring plantation.

Elizabeth wrote, “Some nights I still wake myself back in that place of darkness.

On such nights, Samuel sits beside me until dawn, speaking gentle words of our present freedom, until the shadows recede.

” What James Langford never understood, what those who view others as property can never comprehend, is that our spirits remained our own even when our bodies were claimed.

This truth was our lantern in the darkest hours and remains our strength as we build this new life.

The Ontario community, founded by the six survivors, flourished for over seven decades.

County records indicate that by 1900 it included over 30 families, a school, and a church.

Descendants of the original six remained in leadership positions, guiding the community through the challenges of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The farm became known for its innovative agricultural methods, many developed by Isaiah, whose knowledge had once been exploited for the profit of others, but now served to nurture a free community.

In 1932, Thomas’s granddaughter, Harriet, returned to Savannah for the first time since the escape almost 90 years earlier.

Her visit documented in a private journal later donated to the Shamberg Center for Research in Black Culture in 1966 described her complex emotions upon seeing the city.

To walk these streets as a free woman, educated and secure in my personhood is to claim a victory that my grandfather and his companions fought for with every fiber of their being.

Yet beneath the beautiful squares and historic buildings, I sense the ghosts of countless others whose stories remain untold, whose resistance went unrecorded.

During her visit, Harriet sought out the sight of Magnolia Heights, by then transformed into an upscale neighborhood with no visible trace of the plantation’s existence.

Using a map drawn by Thomas decades earlier, she located what would have been the position of the hidden chamber where the names had been carved.

Standing on that spot on a bright spring morning, she later wrote that she felt a shuddering in the air, as if the very ground remembered what had transpired there, even if the people walking upon it did not.

Harriet’s journal revealed another purpose to her journey, the recovery of an item her grandfather had mentioned in his final years.

According to family law, Thomas had concealed something of great significance somewhere on the grounds before the escape.

Using his detailed descriptions and working undercover of night, Harriet located a hollow space beneath a stone marker that had once designated the boundary of the Langford property.

Within this space, she found a small metal box containing a diary kept by Elizabeth Stanford, Robert Langford’s mother, and the woman who had secretly taught the five individuals to read and write.

The diary, spanning from 1827 to her death in 1836, documented her growing moral opposition to slavery and her clandestine efforts to provide education, a criminal offense in Georgia at that time.

The final entry dated just days before her death expressed both despair and hope.

I have failed to convince James of the moral abomination that sustains our comfort.

My illness progresses, and soon I will be beyond earthly concerns.

Yet in Robert I see a different spirit forming, a questioning mind that may yet break free of the poisonous assumptions that surround him.

And in those I have taught in secret, I have witnessed such dignity, such capacity for knowledge and goodness, as gives lie to every wretched justification for their bondage.

Perhaps in time, when these artificial distinctions are at last torn down, they and he might meet as equals in the light of a better day.

That Elizabeth’s dying hope eventually manifested, though through means far more torturous than she could have imagined, adds another layer to the complex moral landscape of this narrative.

Her diary, now preserved in the collection of the National Museum of African-American History and Culture, stands as evidence that even within the heart of the slaveolding South, voices of conscience existed, however muted or marginalized they may have been.

In 1945, a historian named Dr.

Joseph Williams embarked on a project to document the oral histories of the oldest living descendants of enslaved people in the American South.

Among those he interviewed was a 103-year-old woman named Claraara Johnson, who had been a child on a plantation neighboring Magnolia Heights.

Her testimony, recorded on primitive audio equipment and later transcribed, included memories passed down from her parents about the strange happenings at the Langford place and the subsequent disappearance of six people.

My mother told me, Clara recounted that for weeks after they vanished, the master wouldn’t let anyone near the boundary with Magnolia Heights.

said there was sickness there, but the house servants whispered it was something else entirely, something the masters feared more than any fever.

They said James Langford had tried to break them in body and spirit, but had instead awakened something that could not be controlled.

Mother said the real story wasn’t that they escaped north.

Lots did that, praise God.

The real story was that they took with them the master’s son, not as captive, but as equal.

That’s what frightened the white folks most, the idea that one of their own could recognize the evil of their ways and choose a different path.

Claraara’s testimony suggested that the story of Magnolia Heights had circulated among enslaved communities as a whispered tale of resistance and possibility.

A narrative that while scarcely acknowledged in official histories, had served as inspiration for those still held in bondage.

When things were at their darkest, she said, someone would always remind us, remember the six who walked away from Magnolia Heights.

It gave people hope that freedom wasn’t just about running north.

It was about reclaiming your humanity and helping others to see theirs.

In 1961, during the height of the civil rights movement, a young activist named Marcus Thompson was arrested during a peaceful protest in Savannah.

While detained, he encountered an elderly police officer who, upon learning Thompson’s interest in local history, shared a story passed down through his family.

The officer’s great-grandfather had been among those who investigated Magnolia Heights after the fire in 1844.

According to family law, the investigators had found more than just the hidden chamber and medical equipment.

In a locked cabinet in James Langford’s study, they discovered journals detailing his correspondence with certain European physicians who had conducted experimental procedures designed to break the will of difficult subjects.

These journals, the officer claimed, had been confiscated by federal authorities and removed from Savannah, their contents deemed too disturbing for public knowledge.

Whether this account was accurate or an embellishment of family legend remains uncertain.

Government archives from that period are fragmentaryary and no official record of such journals has been located.

Yet the story aligns with Thomas’s account of James Langford’s methods and suggests that the horrors of Magnolia Heights may have been part of a broader transnational exchange of techniques for controlling enslaved populations.

a dark counterpart to the networks of resistance exemplified by the Underground Railroad.

Among the artifacts uncovered was a small wooden box containing six locks of hair, each tied with different colored thread along with a note in Thomas’s handwriting.

That which was taken from us as evidence of our different natures, we now preserve as testament to our common humanity.

The note referred to a practice documented among certain slaveholders and racial theorists of the 19th century who collected hair samples from enslaved people as specimens for pseudocientific studies aimed at proving racial differences and justifying the institution of slavery.

In 1964, a graduate student in anthropology named Sarah Richardson conducted an excavation at the former site of the Ontario community founded by the six survivors.

That the survivors had reclaimed this dehumanizing practice and transformed it into a symbol of their shared humanity and solidarity speaks to their profound psychological resilience.

Richardson’s excavation also revealed the foundation of the community’s school within which was found a time capsule containing educational materials developed by the community between 1870 and 1900.

These included innovative teaching tools for reading, mathematics, and history, many created by Martha, who had established the school in 1875.

The materials emphasized critical thinking, moral reasoning, and an understanding of history that centered the experiences of those who had been marginalized in conventional narratives.

A notebook belonging to Martha dated 1881 outlined her educational philosophy.

Having been denied knowledge as a means of control, we now recognize its cultivation as essential to true freedom.

We teach our children not merely to recite facts but to question, to discern, to weigh evidence, and to recognize the dignity inherent in every human being.

In this way, we guard against the emergence of new systems of domination, whatever form they might take.

This emphasis on education as a tool for liberation rather than mere advancement, represented a profound challenge to prevailing educational philosophies of the time.

Martha’s approach anticipated by decades the critical pedagogical methods that would later be advocated by educational reformers in the 20th century.

The Ontario community’s influence extended beyond its immediate geographical boundaries.

Records from various abolitionist and civil rights organizations from 1870 through 1920 show correspondence with community leaders, particularly Robert Langford and Thomas, who provided financial support and strategic advice for ongoing struggles against racial oppression.

their unique perspective.

One as a former slaveholder who had rejected that system, the other as a formerly enslaved person who had maintained his intellectual autonomy despite attempts to break it, offered valuable insights to movements working toward racial justice.

A letter from Robert to Frederick Douglas dated 1877 revealed the depth of his transformation.

Having once been blind to the humanity of those my father claimed as property, and having later been subjected to his attempts to reduce me to a similar state of non-personhood, I occupy a singular position in this ongoing struggle.

I have dwelled on both sides of this artificial divide and can testify that the greater loss of humanity lies with those who deny it in others.

The system damages the oppressor as surely as it damages the oppressed, though in different ways.

This knowledge compels me to support not merely the legal dismantling of structures of oppression, but the deeper work of transforming hearts and minds.

By the early 20th century, as the original six survivors passed away, their legacy continued through both their descendants and the institutions they had established.

The farm community evolved into a center for agricultural innovation, education, and civil rights activism.

During the great migration of the early 20th century, it served as a way station for black Americans moving north, providing temporary shelter, educational opportunities, and connections to employment.

World War I brought new challenges and opportunities.

Records from the Canadian Expeditionary Force indicate that 17 men from the community enlisted, including great grandsons of Samuel, Isaiah, and Thomas.

Their service was motivated in part by a commitment to the democratic ideals that Canada and its allies claimed to be defending.

Ideals that the community had been working to fully realize for decades.

The return of these veterans, having fought for democracy abroad, strengthened the community’s resolve to continue working for full equality and recognition.

Community minutes from a town meeting in 1919 record a statement from William Thomas’s greatgrandson.

Having carried the flag of this nation and risked our lives in its defense, we now rededicate ourselves to the unfinished work of our ancestors.

The creation of a society where all are truly treated as equals, where the worth of a person is measured not by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.

The Great Depression of the 1930s tested the community’s resilience, but the cooperative economic structures established by the founders proved remarkably durable.

While surrounding areas struggled with unemployment and foreclosures, the community maintained relative stability through mutual aid systems, diversified agriculture, and cottage industries developed over decades.

A sociological study conducted in 1937 by researchers from the University of Toronto noted, “The economic resilience of this community during the current crisis appears to stem from institutional structures that prioritize collective well-being over individual accumulation.

These structures emerging from the founders experiences of extreme exploitation represent a conscious rejection of competitive individualism in favor of cooperative economics.

The community’s approach to land ownership was particularly noteworthy.

Rather than adopting the dominant model of individual property rights, the founders had established a modified land trust that ensured access based on need and use rather than speculative value.

This system, initially born of necessity due to legal restrictions on property ownership by formerly enslaved people in many jurisdictions, evolved into a principled alternative to prevailing economic models.

In a journal entry from 1884, Isaiah reflected on this approach.

Having once been considered property ourselves, we approach the ownership of land with different eyes.

The earth sustains all life and belongs ultimately to none of us and to all of us.

We hold it in trust for future generations, including those not of our blood, but of our spirit.

The onset of World War II brought renewed attention to questions of freedom, democracy, and human dignity.

In 1942, Emily, a great granddaughter of Elizabeth, wrote in the community newsletter, “As the world confronts ideologies that explicitly rank human beings as superior or inferior based on arbitrary characteristics, we are reminded of the struggle our ancestors endured against similar classifications.

Their resistance maintained in the face of systematic attempts to break their spirit and deny their humanity offers both inspiration and instruction for the present crisis.

The post-war period saw significant changes in both the community and the broader society.

The civil rights movements in the United States and Canada gained momentum, advancing causes that the six survivors had championed decades earlier.

Community records from this period show active participation in these movements with delegations traveling to major demonstrations and providing financial support to organizations working toward racial equality.

A letter written in 1955 by James, a descendant of Samuel to Martin Luther King Jr.

expressed both support and a sense of historical continuity.

What you and your colleagues are undertaking represents the continuation of a struggle that has spanned generations.

My greatgrandfather and his companions escaped physical bondage more than a century ago, but recognize that true freedom requires the dismantling of systems that categorize and constrain human beings based on arbitrary distinctions.

Their journey from slavery to freedom, from property to personhood, from objects of another’s will to subjects of their own destiny mirrors the journey our entire society must undertake if it is to fulfill its professed ideals.

The discovery of the various documents, artifacts, and oral histories related to the six survivors accelerated in the 1960s as increased scholarly attention to African-American history and the civil rights movement created new contexts for understanding their significance.

What had once been scattered fragments began to coalesce into a more coherent narrative, though gaps and uncertainties remained.

In 1967, a historical marker was proposed for the site of Magnolia Heights, acknowledging both the horrors that had occurred there and the resistance that had emerged.

The proposal faced significant opposition from some local officials and property owners who expressed concern about dwelling on negative aspects of our history and potential impacts on property values.

The ensuing debate documented in city council minutes and local newspaper coverage revealed the ongoing contest over historical memory and its implications for contemporary society.

Supporters argued that honest confrontation with the past was essential for meaningful progress toward justice.

Opponents countered that such markers represented needless provocation and an unhealthy fixation on historical grievances.

The marker was ultimately approved in 1968, 100 years after the dgeraotype of the six survivors had been taken in Ontario, but with text that emphasized their escape and survival rather than the specific conditions they had endured at Magnolia Heights.

The compromised language reflected the continuing tension surrounding public acknowledgement of slavery’s brutality and the forms of resistance it engendered.

That same year, 1968, a reunion of descendants of the six survivors was held in Savannah, bringing together branches of the family that had dispersed across North America.

Over 100 individuals attended, representing five generations of resilience and achievement.

The gathering included a silent vigil at the site of Magnolia Heights and a ceremony at the newly installed historical marker.

During this ceremony, Rachel, a descendant of Martha and a professor of history, address the assembled family members.

We gather here not merely to commemorate suffering, but to celebrate survival.

Not just physical survival, but the preservation of dignity, the maintenance of humanity in the face of systematic attempts to deny it.

Our ancestors legacy is not defined by what was done to them, but by what they did in response, how they maintained their sense of selfhood, how they formed bonds of solidarity, how they created new possibilities where none seemed to exist.

The reunions became an annual tradition alternating between Savannah and the site of the Ontario community.

They served not only as family gatherings, but as opportunities for historical research, intergenerational education, and community service.

Oral histories collected during these reunions added new dimensions to the documented narrative, preserving family stories that had been passed down through generations.

One such story recorded in 1972 came from Harold, a descendant of Isaiah.

According to family tradition, Isaiah had maintained throughout his life a small wooden box containing a single cotton seed.

The seed taken from Magnolia Heights during the escape was never planted but kept as a reminder not of captivity but of transformation.

Isaiah would show it to his children and grandchildren, telling them, “From this same plant came the cloth that bound us and the wealth that blinded those who held us.

But a seed contains not just what has been, but what might be.

In your hands, even the instruments of oppression can become tools for building a more just world.

” Another family tradition maintained by descendants of Elizabeth involved the creation of quilts incorporating small squares of fabric from garments worn by each of the six survivors after their escape.

These freedom quilts, as they came to be known, were passed down through generations as tangible connections to ancestors who had made the journey from enslavement to liberty.

The patterns incorporated subtle references to the Underground Railroad and the Ontario community, legible to those who knew the family history, but appearing as mere decorative elements to outsiders.

The 1970s and 80s brought new scholarly attention to the story of Magnolia Heights as historians began to examine more deeply the psychological dimensions of slavery and resistance.

The journals, letters, and artifacts associated with the six survivors offered rare insights into these aspects, documenting not just the physical brutality of the institution, but the psychological warfare waged against enslaved people and their remarkable capacity for maintaining internal freedom even when externally constrained.

A groundbreaking study published in 1983 by Dr.

Elellanena Wright, a psychologist and descendant of Thomas, examined the psychological strategies employed by the six survivors to maintain their sense of self during captivity and to heal from trauma after escape.

Drawing on family documents and her professional expertise, Wright identified patterns of mutual support, narrative reclamation, and meaning making that enabled her ancestors to not merely survive their experiences, but to transform them into foundations for building new lives and communities.

Wright’s work challenged prevailing clinical approaches to trauma which often pathized survivors responses without recognizing their adaptive and resistant qualities.

Her research influenced a generation of clinicians working with survivors of various forms of oppression and violence, encouraging approaches that acknowledged and built upon survivors inherent resilience rather than focusing exclusively on damage and deficit.

In 1992, a documentary filmmaker named Marcus Johnson, himself a descendant of Robert Langford, created a film titled Six from Magnolia Heights that brought together the historical record, family oral histories and contemporary reflections on the legacy of slavery and resistance.

The film, which won several awards at international festivals, expanded public awareness of the story beyond academic circles.

Johnson’s documentary was particularly noteworthy for its exploration of Robert Langford’s complicated moral position and eventual transformation.

Through interviews with descendants and scholarly analysis, the film examined how exposure to abolitionist thought had planted seeds of doubt in Robert’s mind, how his father’s attempts to control him had deepened his understanding of the enslaved experience, and how his alliance with the five individuals had transformed his understanding of humanity and justice.

The story of the six survivors continues to resonate in the 21st century.

As societies in North America and globally confront legacies of historical injustice and ongoing systems of inequality, their experiences speak to fundamental questions about human dignity, the psychology of oppression and resistance, the possibility of moral transformation, and the creation of community across artificially imposed boundaries.

The wooden figures carved from magnolia wood, now displayed in the National Museum of African-American History and Culture, draw visitors from around the world.

Museum staff report that many visitors stand in silence before these artifacts, moved by their simple eloquence and the complex history they represent.

Some leave notes expressing gratitude to the six survivors for their resistance and resilience.

Others commit themselves to continuing the work of creating a more just and equitable society.

In 2018, on the 150th anniversary of the Dgerara type that showed the six survivors standing as equals before their Ontario farmhouse, a symposium was held at Savannah State University, bringing together descendants, scholars, artists, and activists to reflect on the significance of the Magnolia Heights narrative for contemporary struggles for justice.

The keynote address delivered by Dr.

Michael Richardson, a historian and descendant of both Thomas and Robert Langford through subsequent generations, emphasized the ongoing relevance of the six survivors journey.

Their story challenges us to recognize both the depths of human capacity for cruelty and the heights of our capacity for solidarity and transformation.

They remind us that systems of oppression, however powerful, contain within them the seeds of their own undoing.

For they can never fully extinguish the human spirits yearning for freedom and dignity.

The symposium concluded with the unveiling of a new memorial at the site of Magnolia Heights, replacing the more limited marker installed 50 years earlier.

The new memorial designed by a team that included descendants of the six survivors presents their full story without evasion or euphemism.

It stands as an invitation to confront history honestly, to honor those who resisted dehumanization, and to continue their work of creating communities based on mutual recognition and respect.

As this account draws to a close, it is worth returning to the final lines of the letter sent by the six survivors to the liberator in 1869.

Let our story stand as testament to the darkest capacities of the human soul when it denies the humanity of others and to the enduring power of that humanity to prevail.

We six, once master and owned, now move forward as equals, bearing scars visible and invisible, but determined that the horrors we endured shall not be the end of our story.

Indeed, the horrors of Magnolia Heights were not the end of their story.

Through their resistance, escape, healing, and community building, Samuel, Martha, Isaiah, Elizabeth, Thomas, and Robert transformed a narrative of oppression into one of liberation.

Their legacy lives on in their descendants, in the institutions they created, in the artifacts they left behind, and in the ongoing struggle for a world where no person’s humanity is denied or diminished.

Perhaps the most powerful aspect of their story is not what it tells us about the past, but what it suggests about the future.

That even in the face of systems designed to divide and dehumanize, humans retain the capacity to recognize each other’s inherent worth, to form bonds of solidarity across imposed boundaries, and to create communities based on mutual respect rather than domination and subjugation.

The six candles lit by Thomas’s granddaughter in 1968 have long since burned away.

But the light they symbolized continues to burn in the countless acts of resistance, recognition, and reconciliation undertaken by those who have heard their story and taken its lessons to heart.

In this way, the six who walked away from Magnolia Heights continue their journey not just as figures from a troubling past, but as guides toward a more just and humane future.

News

✈️ U.S. F-15 FIRST STRIKE — ALLEGED CARTEL DRUG LAB ERASED IN SECONDS AS SKY ERUPTS IN A BLINDING FLASH ✈️ What officials described as a precision operation turned the night into daylight, with jets screaming overhead and a suspected production site reduced to smoking rubble in moments, sending a shockwave across the region and a message that the airspace above is no safe haven for hidden empires 👇

The Last Fortress: A Shocking Revelation In the heart of the Mexican jungle, Diego stood at the entrance of the…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: FBI & ICE SHATTER ALLEGED TRUCKING NETWORK WITH SOMALI TIES — 83 ARRESTED, $85M IN CASH AND WEAPONS STACKED AS EVIDENCE 🚨 Before sunrise, federal agents swept through depots and dispatch offices, hauling out duffel bags of currency and seizing firearms while stunned neighbors watched a logistics operation authorities claim was hiding a sprawling criminal enterprise behind everyday freight routes 👇

The Shadows of the Ghost Fleet In the heart of the Midwest, where the snow fell like a blanket over…

🚨 FBI & ICE STORM GEORGIA “CARTEL HIDEOUT” — GRENADE LAUNCHER DISCOVERED AND $900K IN DRUGS SEIZED IN A DAWN RAID THAT SHOCKED THE BLOCK 🚨 What neighbors thought was just another quiet morning exploded into flashing lights and tactical vests as agents swept the property, hauling out weapons and evidence while officials described a months-long investigation that culminated in a swift, coordinated takedown 👇

The Unraveling of Shadows: A Tale of Betrayal and Redemption In the heart of Jackson County, Georgia, the air was…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: DEA & FBI CRUSH ALLEGED CARTEL TRUCKING EMPIRE — HIDDEN ROUTES MAPPED, DRIVERS DETAINED, AND MILLIONS STACKED AS EVIDENCE 🚨 Before sunrise, highways turned into a grid of flashing lights as agents intercepted rigs, cracked open trailers, and traced coded dispatch logs, revealing what officials describe as a logistics web hiding in plain sight behind ordinary freight lanes 👇

The Fall of Shadows: A Cartel’s Empire Exposed In the dimly lit corridors of power, where shadows danced with deceit,…

🚢 U.S. NAVY TRAPS SINALOA CARTEL’S ALLEGED $473 MILLION “DRUG ARMADA” AT SEA — AND THE HIGH-STAKES STANDOFF UNFOLDS UNDER FLOODLIGHTS AND ROTOR WASH 🚢 Radar screens lit up, cutters boxed in fast boats, and boarding teams moved with clockwork precision as authorities described a sweeping maritime interdiction that turned open water into a chessboard, stacking seized cargo on deck while prosecutors hinted the ripples would travel far beyond the horizon 👇

The Abyss of Deceit: A Naval Reckoning In the heart of the Caribbean, where the turquoise waters glimmered under the…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: DEA & FBI DESCEND ON MASSIVE TEXAS LOGISTICS HUB — 52 TONS OF METH SEIZED AS 20 POLITICIANS ALLEGEDLY TIED TO A SHADOW NETWORK ARE THRUST INTO THE SPOTLIGHT 🚨 What began as a quiet federal probe detonated into a sweeping raid of warehouses and boardrooms, with agents hauling out towering stacks of evidence while stunned insiders whisper that the real shockwave isn’t just the drugs — it’s the powerful names now facing intense scrutiny 👇

Shadows of the Underground: The Texas Cartel Unveiled In the heart of Texas, where the sun sets over sprawling landscapes,…

End of content

No more pages to load