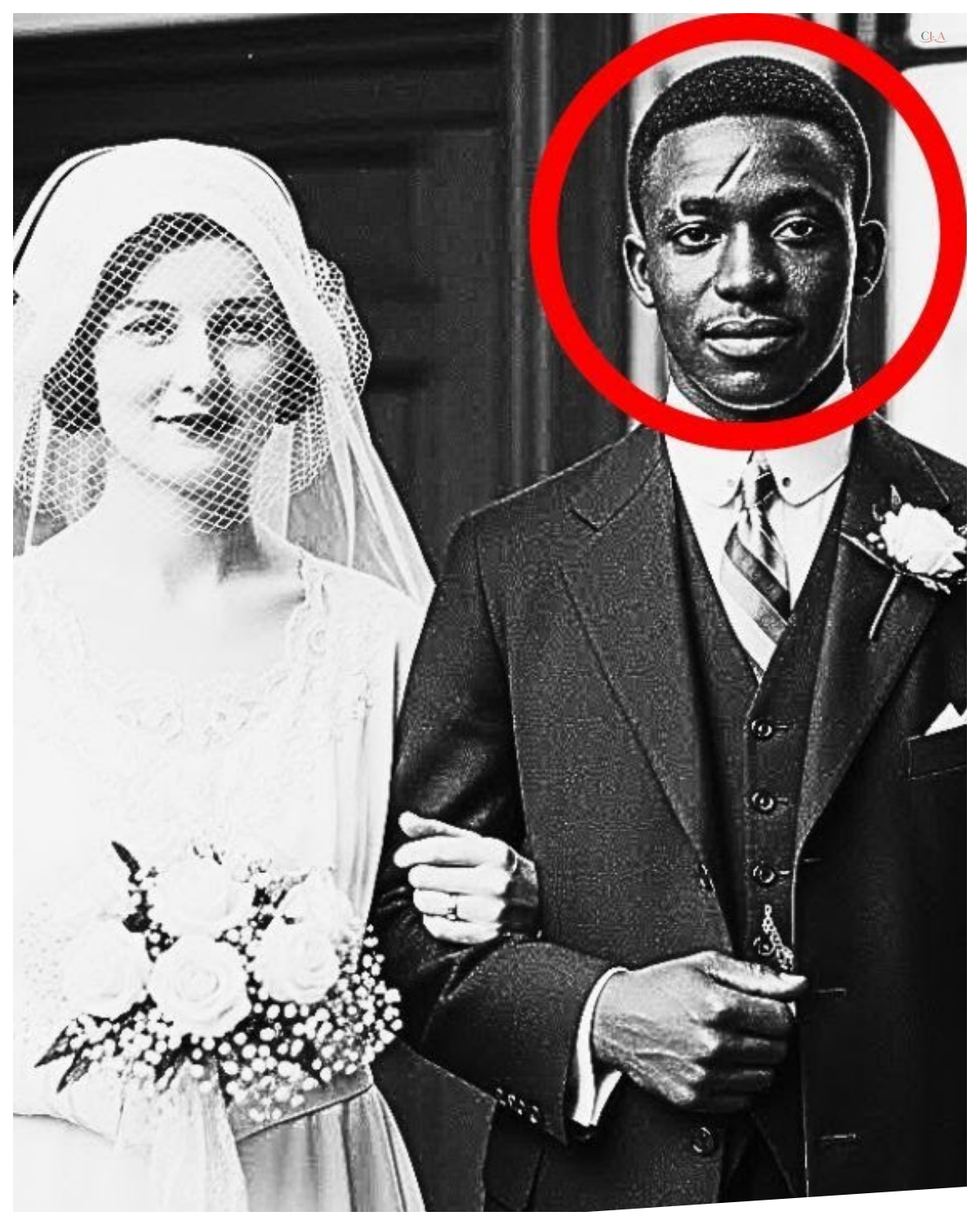

The photo that history tried to erase.

The forbidden wedding of 1920.

The attic smelled of dust and forgotten memories.

Maya Johnson wiped sweat from her forehead as she sorted through her grandmother’s belongings.

3 weeks after the funeral, cardboard boxes lined the wooden floor, each one a time capsule waiting to be opened.

The Chicago summer heat made the small space nearly unbearable, but Maya had promised her mother she would finish going through everything before the estate sale.

She pulled open a leather trunk wedged behind an old mirror.

Inside, beneath yellowed newspapers from 1920, her fingers touched something solid wrapped in cloth.

Maya carefully unfolded the fabric to reveal a wooden frame.

Her breath caught.

The photograph showed a young couple on their wedding day.

The woman was white, wearing a simple ivory dress with delicate lace sleeves holding a small bouquet of wild flowers.

Her smile was radiant, but her eyes held something else.

Determination, perhaps defiance.

The man beside her was black, dressed in a military uniform, his posture rigid and proud, one hand gently placed on her waist.

His expression mixed joy with what looked like fear.

Mia’s hands trembled.

She had never seen this photograph.

Her grandmother, Elizabeth, had been white, that much she knew.

But the family had always been tight-lipped about her grandfather.

Growing up, Mia had been told he died before she was born, that he had been a good man, nothing more.

She turned the frame over.

On the back, written in faded ink, Elizabeth Hartwell and Thomas Johnson.

April 3rd, 1920.

Our first day as one.

God protect us.

The formal studio backdrop and professional quality suggested this had been taken by someone who knew what they were doing, despite the secrecy such a union would have required.

Maya noticed the photographers’s stamp in the corner.

Green’s Photography, Southside, Chicago.

She pulled out her phone and photographed the image, then immediately called her mother.

The phone rang four times before going to voicemail.

Maya’s heart pounded as she stared at the faces in the photograph.

Her grandfather had been black.

Her grandmother had married him in 1920 when interracial marriage was illegal in most states when the Kulux Clan was at the height of its power.

Maya sat back against the trunk, the photograph held carefully in her lap.

The couple’s eyes seemed to look directly at her across a century of silence.

What had happened to them? Why had this photo been hidden? And why had no one ever told her the truth? She knew then that she had to find out.

This wasn’t just a photograph.

It was evidence of a love that had been deliberately erased from her family’s history.

Chicago, March 1920.

Thomas Johnson stepped off the train at Union Station.

His military duffel bag slung over his shoulder.

The Grand Hall buzzed with travelers, vendors shouting about newspapers, and the constant whistle of arriving trains.

He had been gone for two years.

First training, then fighting in France with the 370th Infantry Regiment, one of the few black units to see combat.

The uniform he wore had earned him respect in Europe.

French civilians had welcomed him, treated him as a hero.

But now, back on American soil, he felt the familiar weight of eyes upon him, suspicious, dismissive, sometimes openly hostile.

Thomas made his way through the crowd toward the south side, where his mother lived in a modest apartment on 35th Street.

The neighborhood had transformed during his absence.

The great migration had brought thousands of black families from the south, fleeing Jim Crow and searching for factory work and dignity.

Buildings that had once been empty now overflowed with life.

Children playing in the streets.

Music pouring from open windows.

The smell of cooking filling the air.

His mother, Ruth, wept when she saw him standing in the doorway.

She held him for a long time, her hands patting his back as if confirming he was truly real.

“My boy,” she whispered.

“Thank God you’re home.

” Over dinner, she filled him in on neighborhood news.

Jobs were scarce, even for veterans.

The meat packing plants and steel mills hired black workers, but paid them less and gave them the most dangerous positions.

Race riots had erupted the previous summer, leaving dozens dead and hundreds homeless after white mobs attacked black neighborhoods.

“It’s not what you fought for, is it?” Ruth said quietly, watching her son’s face darken with each story.

Thomas shook his head.

“In France, I was a soldier here.

I’m just another problem they want to disappear.

” The next morning, Thomas visited the office of the Chicago Defender, the city’s leading black newspaper.

He had studied law for two years before the war and hoped to resume his education.

The editor, a sharpeyed man named Robert Abbott, looked over Thomas’s references.

“You’re qualified,” Abbott said.

“But law schools aren’t taking Negro students right now.

Not officially, anyway.

” He paused, studying Thomas.

“There’s a community legal clinic on 47th Street.

They need someone who can help people navigate housing contracts and labor disputes.

It doesn’t pay much.

I’ll take it,” Thomas said without hesitation.

That afternoon, Thomas walked to the clinic located above a barber shop.

The stairs creaked under his weight.

When he reached the top, he pushed open the door and found himself face to face with a young white woman organizing files behind a desk.

She looked up, startled, their eyes met.

Neither of them knew it yet, but in that moment, everything changed.

Elizabeth Hartwell had been working at the Southside Legal Clinic for eight months, and each day brought new challenges that her upbringing in Oak Park had never prepared her for.

the daughter of a railroad executive.

She had been expected to marry well, host dinner parties, and fade gracefully into the background of someone else’s life.

Instead, she had studied nursing, volunteered at settlement houses, and eventually found her way to this cramped office, where she helped people who had nowhere else to turn.

When the tall soldier walked through the door that March afternoon, Elizabeth felt something shift in her chest.

His eyes were intelligent and kind, despite the weariness she saw in them.

He carried himself with a dignity that seemed almost defiant.

I’m Thomas Johnson, he said, his voice deep and measured.

Mr.

Abbott sent me.

He said you might need help with legal work.

Elizabeth stood smoothing her skirt nervously.

Elizabeth Hartwell.

Yes, we desperately need help.

Are you a lawyer? Not yet.

I was studying law before the war.

He gestured to his uniform.

Just got back from France two days ago.

Over the next hour, they discussed the clinic’s work.

Helping families facing eviction.

Workers cheated out of wages.

Veterans denied benefits.

they had earned.

Thomas asked thoughtful questions and took careful notes.

Elizabeth found herself drawn to the way he listened, really listened to everything she said.

When her supervisor, Mr.

Patterson, returned from court, he looked surprised to see Thomas.

Mrs.

Hartwell, who is this? Elizabeth, please.

This is Thomas Johnson.

Mr.

Abbott recommended him.

He has legal training, and I see.

Patterson’s tone cooled noticeably.

He studied Thomas for a long moment.

The work here is volunteer.

We can’t pay you.

I understand, sir, and you’ll need to be careful.

Some of our clients might not be comfortable working with.

He left the sentence unfinished.

Thomas’s jaw tightened, but his voice remained even.

I fought for this country, sir.

I think I can handle uncomfortable situations.

Patterson nodded slowly.

Very well.

You can start Monday, 8:00 sharp.

After Patterson left, Elizabeth turned to Thomas, her cheeks flushed with embarrassment.

I apologize for Don’t, Thomas said gently.

I know how things are, but thank you for speaking up for me.

Over the following weeks, they worked side by side.

Elizabeth found herself arriving earlier and staying later, drawn by conversations that ranged from legal cases to books they had read, music they loved, dreams they harbored.

Thomas spoke French fluently and told her stories about Paris, about cafes where black soldiers were welcomed, where they could sit at any table and order any drink.

“It sounds like freedom,” Elizabeth said one evening as they locked up the office.

“It was,” Thomas replied.

For a moment, I forgot what it felt like to be constantly judged by my skin.

Then I came back here and remembered.

Goodness, Elizabeth’s father had forbidden her from working in that neighborhood.

But she had moved into a boarding house and took the street car south every day.

Her family had stopped speaking to her months ago.

She told herself it didn’t matter, that she was doing meaningful work.

But the truth, which she was only beginning to admit to herself, was that she stayed because of Thomas.

The spring of 1920 brought warmth to Chicago streets and growing tension to its neighborhoods.

Elizabeth and Thomas fell into an easy rhythm at the clinic.

He handled legal research while she managed client intake and correspondence.

They made a good team, complimenting each other’s strengths, anticipating each other’s needs.

One rainy April evening, they were the last ones in the office.

Thomas sat at the desk reviewing a property deed by lamplight, his brow furrowed in concentration.

Elizabeth stood by the window, watching water stream down the glass.

“My father came to the boarding house today,” she said quietly.

Thomas looked up immediately.

What did he say? That I’m throwing away my life.

That I’m disgracing the family by working in a colored neighborhood.

She turned to face him.

He said, “If I don’t come home and start acting like a proper woman, I’ll be cut off completely.

No inheritance, no family, nothing.

” “What did you tell him?” Elizabeth’s eyes met his.

I told him I’m exactly where I need to be.

Thomas stood slowly, setting down his pen.

Elizabeth, you don’t have to sacrifice everything for this work.

Your family, your future.

What future? She moved closer.

Marrying some banker’s son who sees me as a decoration? Hosting parties and pretending to care about things that don’t matter? She shook her head.

I found something real here.

I found purpose.

I found She stopped, the words catching in her throat.

Thomas crossed the room until he stood directly in front of her.

The air between them felt charged, dangerous.

“You found what?” he asked softly.

“You,” Elizabeth whispered.

“I found you.

” For a long moment, neither moved.

Thomas’s hand reached up slowly, carefully, as if approaching something fragile and precious.

His fingers brushed her cheek.

“Do you understand what you’re saying, what it would mean? I understand that I’ve never felt this way before.

I understand that when you’re not here, I count the hours until you return.

I understand that you’re the most remarkable person I’ve ever met, and I don’t care what color your skin is or what anyone else thinks about it.

” Elizabeth, her name on his lips, was both a prayer and a warning.

They would destroy us.

Your family, my community, everyone would turn against us.

The law itself.

I know the laws, Thomas.

I know the risks.

And I’m telling you that I don’t care.

Tears filled her eyes.

I love you.

I’ve loved you since the day you walked through that door.

I Thomas closed his eyes, his hand still cradling her face.

When he opened them again, Elizabeth saw her own feelings reflected back.

Love, fear, impossible hope.

I love you, too, he said.

God help me.

I love you more than I’ve ever loved anything, but loving you could cost you everything.

Then let it, Elizabeth said fiercely, because losing you would cost me more.

He kissed her, then gently at first, then with an urgency that spoke of all the words they couldn’t say, all the impossible dreams they dared to dream.

Outside, thunder rolled across the city.

Inside that small office, two people made a choice that would change their lives forever.

Planning a wedding that could land them both in jail required creativity and trusted allies.

Thomas reached out to Reverend Marcus Williams, an elderly minister at Ebenezer Baptist Church who had known his family for decades.

The Reverend listened carefully as Thomas explained the situation, his weathered face thoughtful.

“Son, you know what you’re asking for.

” Reverend Williams said, “Ill don’t have laws against interracial marriage like some states, but that don’t mean folks won’t come after you.

Police can find other charges.

Employers can fire you.

Landlords can evict you.

And that’s if you’re lucky.

” I know, Reverend, but I fought in France believing America could be better.

Maybe Elizabeth and I can’t change everything, but we can live our truth.

The old man smiled sadly.

Love makes us brave and foolish in equal measure.

He sighed.

I’ll marry you, but it has to be private.

Very private.

Elizabeth told her landl she was visiting a sick aunt.

On April 3rd, 1920, she dressed in a simple ivory gown she had made herself, her hands shaking as she buttoned each tiny clasp.

She had no family to help her, no bridesmaids to fuss over her hair, just a small bouquet of wild flowers Thomas had somehow managed to find.

They met at the church at dawn when the streets were still empty.

Only four people attended.

Reverend Williams, his wife Clara, who served as witness, Thomas’s mother, Ruth, and a photographer named Joshua Green, whom Thomas trusted absolutely.

Ruth had cried when Thomas told her, not from disappointment.

She had seen the way her son looked at Elizabeth, had met the young woman, and recognized the genuine love between them, but from fear.

They’ll hurt you,” she had whispered.

“Both of you.

” “Maybe,” Thomas had replied.

“But we’ll face it together.

” “Oh, dear.

” Now, in the quiet sanctuary, Ruth watched her son marry a white woman and prayed for their protection.

Clara played the piano softly.

Morning light filtered through the stained glass windows, casting colors across the worn wooden pews.

Elizabeth and Thomas stood before Reverend Williams, hands clasped tightly.

Thomas wore his military uniform, the medals on his chest catching the light.

Elizabeth wore no veil.

She wanted to face this moment clearly, honestly.

Do you, Thomas Johnson, take this woman to be your lawfully wedded wife, to love and cherish and sickness and health, knowing the trials you will face until death do you part? I do, Thomas’s voice was steady.

Do you, Elizabeth Hartwell, take this man to be your lawfully wedded husband to love and cherish in sickness and health, knowing the trials you will face until death do you part? I do.

Elizabeth’s voice rang clear in the empty church.

Then by the power vested in me, I pronounce you husband and wife.

Reverend Williams eyes were damp.

May God watch over you both.

You’re going to need him.

Thomas kissed Elizabeth, and for one perfect moment, the world outside didn’t exist.

Joshua Green captured that moment with his camera, the click of the shutter barely audible, but preserving forever the joy and defiance in their faces.

They had no reception, no celebration.

Instead, they gathered briefly in the church basement where Clara had prepared coffee and sweet rolls.

Ruth hugged Elizabeth tightly.

“You’re my daughter now,” she said.

“When things get hard, and they will, you remember you’ve got family.

” An hour later, Elizabeth returned to her boarding house and Thomas to his mother’s apartment.

They had agreed to keep the marriage secret for now, to find housing and make plans before announcing their union.

But secrets, especially ones that challenged the very foundation of social order, never stayed hidden for long.

Thomas and Elizabeth found a small apartment on the edge of Bronzeville in a building owned by a white landlord who rarely visited.

They created a careful fiction.

Thomas rented the apartment officially, and Elizabeth was his housekeeper who lived in.

The lie tasted bitter, but it kept them safe.

Elizabeth quit the clinic, unable to explain her living situation.

She found work doing laundry and mending for wealthy families in Hyde Park, jobs that kept her invisible.

Thomas continued at the clinic during the day and studied law books at night, determined to pass the bar exam despite the obstacles.

Their daily life became an elaborate performance.

In public, they maintained careful distance.

Elizabeth walked three steps behind Thomas on the street.

They never touched where others could see.

In shops, she addressed him as Mr.

Johnson with exaggerated formality.

But once their apartment door closed behind them, they could finally breathe.

Elizabeth would collapse into Thomas’s arms, the tension draining from her shoulders.

They would eat dinner together at their small kitchen table, talking about their days, making plans for the future, dreaming of a time when they wouldn’t have to hide.

“Do you regret it?” Thomas asked one evening, watching Elizabeth darn his socks by lamplight.

She looked up, genuinely puzzled.

Regret what? This? All of this? You could have had an easy life.

Elizabeth set down her needle and thread, crossing to where he sat.

She took his face in her hands.

Thomas Johnson, you listen to me.

I have never been happier than I am right now.

Yes, I’m scared sometimes.

Yes, it’s hard.

But I wake up every morning next to the man I love, and that’s worth everything I gave up.

By June, Elizabeth discovered she was pregnant.

The news brought both joy and terror.

A child would make everything more complicated and more dangerous.

Mixed race children faced particular cruelty, belonging fully to neither world.

Thomas held Elizabeth through her tears that night.

“We’ll protect them,” he promised.

“Whatever it takes, we’ll keep our family safe.

” Elizabeth’s pregnancy forced new calculations.

They needed more money, more security.

Thomas took a second job loading trucks at the railyard, leaving before dawn and returning after dark.

Elizabeth continued her laundry work until her belly grew too large to hide.

Ruth visited regularly, bringing food and advice, teaching Elizabeth the practical skills her privileged upbringing had never required.

The two women grew close, bound by their love for Thomas and their shared understanding of what this family meant.

“You’re braver than I ever was,” Ruth told Elizabeth one afternoon as they folded sheets together.

“I don’t feel brave.

I feel terrified most of the time.

That’s what bravery is, child.

Being terrified and doing it anyway.

In their rare moments of peace, Thomas and Elizabeth would lie in bed, his hand resting on her growing belly, feeling the baby kick.

What should we name them? Elizabeth would ask.

Something strong, something that means hope.

They chose names carefully.

Daniel for a boy, meaning God is my judge, and Grace for a girl, meaning unmmerited favor.

Either way, their child would need divine protection in the world awaiting them.

By autumn, Elizabeth’s condition could no longer be hidden.

Neighbors began to whisper.

The landlord started asking questions.

Thomas came home one October evening to find their apartment door marked with a crude white cross and chalk, a warning from the clan.

That night, Thomas erased the mark and began making plans they both had dreaded.

“We need to leave Chicago,” he said quietly.

“It’s not safe anymore.

” Elizabeth nodded, one hand protectively cradling her belly.

Their brief moment of happiness was ending.

The running was about to begin.

Thomas spent two weeks making discreet inquiries.

A fellow veteran told him about Milwaukee, where industrial jobs were plentiful and the black community was smaller but tight-knit.

Another friend mentioned Detroit, where automobile factories hired anyone willing to work.

But everywhere they considered, the same problems existed.

Anti-misogenation sentiment, clan presence, and the constant threat of violence.

Finally, Thomas found a possibility through a letter from a French officer he had served under.

The man, Marcel Dubois, had returned to Montreal and wrote that Canada might offer more tolerance.

The laws are different here, Marcel wrote.

Not perfect, but perhaps better than what you face.

On November 15th, 1920, Thomas and Elizabeth packed everything they owned into two suitcases.

Elizabeth was 7 months pregnant, her movement slow and careful.

Ruth insisted on coming to the train station, though Thomas worried about the risk.

They arrived at Union Station before dawn.

The massive hall echoed with the sounds of departure, whistles blowing, porters calling out destinations, families saying goodbye.

Thomas purchased two tickets to Detroit under assumed names.

Mr.

and Mrs.

Robert Miller.

Ruth pulled Elizabeth into a tight embrace.

You take care of my son and that grandbaby, and you remember you’re my daughter no matter where you go.

Elizabeth wept.

In the months of hiding, Ruth had become the mother her own had never been.

practical, warm, unshakably loyal.

I’ll write when we can, Thomas promised his mother.

When it’s safe.

If it’s safe, Ruth corrected, her eyes wet.

You focus on staying alive.

I’ll trust God to bring us back together someday.

They boarded the train separately.

Thomas took his seat in the colored section while Elizabeth sat in a whites only car three carriages ahead.

The separation felt like a physical wound.

For the next 12 hours, they would pretend to be strangers.

The train pulled away from Chicago as the sun rose, painting the skyline in shades of orange and gold.

Elizabeth pressed her forehead against the cold window, watching the city disappear.

Everything she had known was in that city.

Her childhood, her family, the brief, beautiful months of her secret marriage.

Thomas sat rigid in his seat, military training, keeping his face neutral even as his heart pounded.

He had survived the trenches of France, had faced German artillery and poison gas.

But this fear was different.

He wasn’t just responsible for himself anymore.

He had a wife, an unborn child, a future that felt terrifyingly fragile.

At the Detroit station, they disembarked separately.

Thomas waited on the platform while Elizabeth collected her bag.

Finally, when enough time had passed, they walked in the same direction, still apart, still careful.

They found a boarding house in Black Bottom, Detroit’s negro neighborhood.

The land lady, Mrs.

Patterson, looked them over suspiciously when Elizabeth appeared at Thomas’s door an hour after he checked in.

I don’t run that kind of establishment, she said sharply.

She’s my wife, Thomas said quietly, closing the door behind them.

Mrs.

Patterson’s eyes widened.

She glanced down the hallway, then stepped inside and shut the door.

Are you insane? Do you know what they do to couples like you? We know, Elizabeth said, lifting her chin.

We’re married legally.

We’re not doing anything wrong.

Legal and safe are two different things, honey.

But Mrs.

Patterson’s expression softened as she looked at Elizabeth’s swollen belly.

How far along? 7 months.

The older woman sighed deeply.

Lord have mercy.

All right, you can stay, but you keep to yourselves.

Understand? No entertaining visitors, no drawing attention, and for heaven’s sake, don’t tell anyone you’re married.

They agreed to her terms.

That night, finally alone together after the longest day of their lives, Thomas and Elizabeth held each other in the narrow boarding house bed.

“It’s going to be like this everywhere, isn’t it?” Elizabeth whispered.

always hiding, always afraid.

Thomas kissed her forehead.

Maybe, but we’re together, that’s what matters.

Two months later, on a freezing January night in 1921, Elizabeth went into labor.

The pain started at midnight.

Elizabeth gripped Thomas’s hand, her face pale and damp with sweat.

“It’s time,” she whispered.

Thomas’s mind raced.

“They couldn’t go to a white hospital.

They would ask questions, demand documentation, possibly arrest them.

The nearest colored hospital was across town, too far for Elizabeth to travel in her condition.

Mrs.

Patterson, awakened by Elizabeth’s cries, took charge immediately.

There’s a midwife two blocks over, Mrs.

Beatatric Washington.

She’s delivered half the babies in Black Bottom.

I’ll fetch her.

You stay with your wife.

Thomas had faced enemy fire without flinching, but watching Elizabeth in pain undid him.

He helped her breathe through contractions, his own breathing matching hers, feeling utterly helpless.

Mrs.

Washington arrived within 20 minutes, a sturdy woman in her 60s with calm eyes and capable hands.

She assessed Elizabeth quickly and turned to Thomas.

Boil water, get clean towels, and then get out.

You’re making her nervous, hovering like that.

For the next 6 hours, Thomas paced the hallway outside their room.

He heard Elizabeth cry out, heard Mrs.

Washington’s steady voice coaching her through each push.

He prayed more fervently than he ever had in the trenches.

Finally, just as dawn broke on January 18th, 1921, he heard a new sound, a baby’s cry, thin and fierce and perfect.

Mrs.

Washington opened the door, a bundle in her arms.

Come meet your daughter, Mr.

Miller.

Thomas stepped into the room.

Elizabeth lay exhausted against the pillows, her hair plastered to her forehead, but her smile was radiant.

Mrs.

Washington placed the baby in his arms.

She was tiny, wrinkled with a dusting of dark hair.

Her skin was a beautiful blend, not quite as dark as Thomas’s, not quite as pale as Elizabeth’s.

Her eyes, when they fluttered open, were deep gray.

“Grace,” Elizabeth whispered.

Her name is Grace.

Thomas couldn’t speak.

He stared at his daughter, this impossible miracle, this living proof of everything he and Elizabeth had risked.

She wrapped her small hand around his finger, and something in his chest broke open.

“She’s perfect,” he finally managed.

Over the next weeks, Elizabeth recovered while Mrs.

Patterson and Mrs.

Washington became unexpected allies.

They brought food, offered advice, and kept curious neighbors at bay.

Grace proved to be a good baby.

She nursed well, slept in manageable stretches, and gazed at her parents with solemn curiosity, but their brief peace couldn’t last.

In March, Thomas came home from his factory job to find Mrs.

Patterson waiting, her face grave.

“There’s been talk,” she said quietly.

“Some of the other tenants noticed the baby.

They’re asking questions.

Why a colored man has a white woman in his room? Why she had a baby here? Someone mentioned getting the police involved.

” Thomas felt ice in his veins.

“When? Soon, maybe days.

You need to leave.

That night, Thomas and Elizabeth made plans by lamplight while Grace slept in a drawer lined with blankets, their makeshift bassinet.

They had saved almost nothing.

Thomas’s factory wages barely covered rent and food.

Montreal, Thomas said.

That’s still our best option.

Marcel said he could help us find work, housing.

How do we get there with a two-month old baby? Elizabeth’s voice shook.

She’s so small, Thomas.

What if she gets sick? What if we don’t have a choice? Thomas pulled Elizabeth close.

We’ll figure it out.

We always do.

Three days later, with Grace bundled against Elizabeth’s chest and their belongings reduced to a single bag, they boarded a northbound train.

Mrs.

Patterson pressed money into Thomas’s hand at the door more than their rent had been.

For the baby, she said gruffly.

“Now go, and may God protect you.

” As the train pulled away from Detroit, Elizabeth looked down at Grace’s sleeping face.

“Where will we be safe?” she asked Thomas.

“He had no answer.

They were fugitives from a society that refused to accept their existence.

Running toward a future they couldn’t see, carrying the most precious thing in the world.

The journey to Montreal took three days, changing trains twice and navigating border crossings with forged documents that cost the most of Mrs.

Patterson’s money.

At the Canadian border, a guard studied their papers.

Thomas listed as a railroad worker.

Elizabeth as his employer’s sister traveling north with her infant.

The guard looked at Grace, who chose that moment to wake and cry.

“She yours?” he asked Thomas.

Thomas’s heart stopped.

Elizabeth stepped forward quickly.

The baby is mine.

Mr.

Miller works for my family.

He’s helping me travel.

The guard’s eyes moved between them, suspicious, but not certain.

Finally, he stamped their papers.

Um, welcome to Canada.

Marcel Dubois met them at Windsor Station in Montreal.

The French officer looked older than Thomas remembered, but his embrace was warm.

Monomy, you made it.

He kissed Elizabeth’s cheeks in the French manner, making her blush and cooed over grace.

Unbel Patit Marcel had arranged a small apartment in Verdon, a working-class neighborhood where French and English speakers mixed, where immigrants from a dozen countries crowded the streets.

“Here, people mind their own business,” Marcel explained.

“You’re just another young family trying to survive.

For the first time in months, Thomas and Elizabeth could walk down the street together without fear.

They could push Grace in a secondhand pram,” Marcel had found.

They could hold hands in public.

The relief was so profound that Elizabeth cried the first time Thomas put his arm around her waist as they walked to the market.

Marcel helped Thomas find work at a textile factory.

The pay was modest but steady.

Elizabeth took in sewing at home, her needle flying through fabric while Grace napped.

Slowly, carefully, they built something resembling a normal life.

In June 1921, Elizabeth discovered she was pregnant again.

This time, the news brought only joy.

Their son, Daniel, was born in February 1922 at Montreal General Hospital.

The nurses were French Canadian, practical, and unbothered by the couple’s racial difference.

One nurse even complimented them on their beautiful children.

“You see,” Elizabeth said to Thomas as they walked home with newborn Daniel bundled against the February cold.

“We can have this, a real life, a family.

” But Thomas remained cautious.

He had learned too well that safety was always temporary.

He changed their surname legally to Miller, burning any documents that said Johnson.

He taught Grace to call him Papa and Elizabeth Mama, but never to mention Chicago or Detroit to anyone.

By 1924, they had a third child, another daughter they named Marie.

The apartment overflowed with life.

Toys on the floor, laundry hanging from lines stretched across the kitchen, children’s laughter, replacing the silence of fear they had lived with for so long.

Thomas studied at night and eventually passed the Quebec Bar exam.

His law practice was small, helping other immigrants navigate the complex Canadian system, but it was honest work that used his mind.

Elizabeth joined a women’s church group, finding friendship and community for the first time since leaving Chicago.

One evening in 1925, Thomas came home to find Elizabeth crying at the kitchen table, a letter in her hands.

“What is it?” he asked, alarmed.

“Ruth,” Elizabeth whispered.

“Your mother? She’s sick.

She wants to see the children before she dies.

” Thomas read the letter, forwarded through several intermediaries to protect them.

His mother’s handwriting was shaky, her words brief.

Cancer, not long now.

Please.

Thomas and Elizabeth looked at their three children playing on the floor.

Grace, four years old and serious.

Daniel, three and full of questions.

Marie, barely one and crawling everywhere.

They had built a safe life here.

Going back to the United States, even for a visit, meant risking everything.

But Ruth was dying.

She had given up everything to help them.

Had defended their love when everyone else condemned it.

“We have to go,” Elizabeth said quietly.

“We have to let her meet her grandchildren.

” Thomas nodded slowly, though fear twisted in his gut.

We’ll be careful.

Quick trip in and out.

Neither of them imagined how wrong things would go.

In August 1925, the family took the train south under their new names, the Miller family, visiting relatives in Chicago.

Thomas wore civilian clothes instead of his uniform.

Elizabeth kept the children close, constantly vigilant.

Ruth had moved to a small house on the far south side, away from the neighborhood where people might remember Thomas.

When they arrived, she stood at the door, impossibly frail, leaning on a cane.

But her face transformed when she saw her grandchildren.

“Oh,” she breathed.

“Oh, Thomas, look what you made.

” For 3 days, they stayed hidden in Ruth’s house.

She held each grandchild, memorized their faces, told them stories about their father as a boy.

Grace sat beside her great-grandmother for hours, absorbing every word.

Daniel brought her flowers from the garden.

Marie fell asleep in her arms.

Thomas photographed them together.

Ruth surrounded by her grandchildren, Elizabeth beside her.

He wanted her to have something to hold during the difficult days ahead.

On their fourth day, everything fell apart.

A neighbor, Mrs.

Coleman, came to check on Ruth.

She saw Elizabeth through the window, saw the children with their ambiguous features, saw Thomas emerge from the back room.

Mrs.

Coleman’s face went hard.

She left without speaking.

“She recognized me,” Thomas said quietly.

“We need to leave now.

” They packed frantically.

Ruth pressed money into their hands.

Money she couldn’t spare.

Go, she urged before they come.

But it was too late.

As they prepared to leave, three police cars pulled up outside.

Officers pounded on the door.

Thomas Johnson, we know you’re in there.

You’re under arrest for violation of Illinois moral statutes.

Thomas looked at Elizabeth and the children.

Grace’s eyes were wide with terror.

Daniel started to cry.

Out the back, he whispered.

Take the children and run.

I’m not leaving you, Elizabeth said fiercely.

You have to.

If they arrest us both, what happens to Grace, Daniel, Marie? He kissed her hard.

Go to Montreal.

I’ll find you.

I promise.

Ruth grabbed Elizabeth’s arm.

There’s a fence behind the garden.

It leads to an alley.

Go now before they surround the house.

Elizabeth wanted to argue to stay, but the children needed her.

With tears streaming down her face, she gathered them.

Grace held Daniel’s hand.

Elizabeth carried Marie.

As the police broke down the front door, they slipped out the back.

Ruth watched them disappear over the fence, then turned to face the officers, giving Thomas precious seconds.

Thomas was arrested, handcuffed, and dragged to a police car while neighbors gathered to watch.

The charges were vague, disturbing the peace, fraud, suspected violation of morals laws.

The real crime was living as he chose, loving who he loved.

But Thomas had prepared for this possibility.

Marcel had given him the name of a lawyer in Chicago, someone who believed in civil rights.

Within 24 hours, the lawyer had Thomas released on bail with help from sympathetic black civil rights organizations.

Thomas didn’t go back to Ruth’s house.

He went directly to Union Station and took the first train north, looking over his shoulder the entire way, expecting police to stop him at any moment.

When he arrived at their Montreal apartment 3 days later, Elizabeth opened the door and collapsed into his arms.

“I thought they would keep you.

I thought I’d lost you.

” “Oh, never.

” Thomas promised.

“We’re together, that’s all that matters.

” Ruth died two weeks later.

They couldn’t attend the funeral.

It was too dangerous to return.

Thomas grieved alone, holding the photograph of his mother, surrounded by his children, the last moment of joy she had known.

Maya Johnson sat in her grandmother’s attic, the wedding photograph still in her hands, tears streaming down her face.

Now she understood the silence, the carefully guarded family history, the way her grandmother Elizabeth had always seemed, both happy and haunted.

They had survived against impossible odds, against laws and violence and hatred.

Thomas and Elizabeth had built a family, raised children, lived a love that society said couldn’t exist.

Maya pulled out her phone and called her mother again.

This time, she answered, “Mom,” Mia said, her voice thick with emotion.

“I found something, and I need you to tell me everything.

” The photograph had been hidden for decades, but its truth refused to stay buried.

Thomas and Elizabeth’s great-granddaughter would make sure their story and their courage was finally remembered.

News

It Was Just a Photo Between Friends — Until Historians Uncovered a Dark Secret Hidden in the Shadows and the Smiles Suddenly Felt Fake 📸 — At first it looked like harmless laughter frozen in sepia, arms slung over shoulders, the kind of memory you’d tuck into a family album, but once experts enhanced the image they spotted a chilling detail tucked between them, and those cheerful expressions started to feel staged, like two people pretending everything was fine while hiding something they prayed no one would ever see 👇

It was just a photo between friends. But historians have uncovered a dark secret. Dr.James Patterson had spent his academic…

This 1898 Photograph Hides a Detail Historians Completely Missed — Until Now, and What They Found Has Them Questioning Everything 📸 — For decades it gathered dust in a quiet archive, labeled “ordinary,” dismissed as just another stiff Victorian snapshot, until a high-resolution scan exposed one tiny, impossible detail lurking in the background, and suddenly the smiles looked fake, the poses suspicious, and experts realized they weren’t staring at a memory… they were staring at a secret frozen in time 👇

This 1888 photograph hides a detail historians completely missed until now. The basement archives of the Charleston County Historical Society…

This Portrait of Two Friends Seemed Harmless — Until Historians Spotted a Forbidden Symbol Hidden Between Them and Everything Fell Apart ⚠️ — At first it was just two smiling companions shoulder-to-shoulder in stiff old-fashioned suits, the kind of wholesome image you’d frame without a second thought, but a closer scan revealed a tiny, outlawed mark tucked into the shadows, and suddenly the photo wasn’t friendship… it was rebellion, secrecy, and a message never meant to survive the century 👇

This portrait of two friends seemed harmless until historians noticed a forbidden symbol. The afternoon sun filtered through the tall…

Experts Thought This 1910 Studio Photo Was Peaceful — Until They Zoomed In and Saw What the Girl Was Holding, and the Entire Room Went Cold 📸 — At first it looked like another gentle Edwardian portrait, lace dress, soft lighting, polite smile, but when archivists enhanced the image they noticed her tiny fingers clutching something oddly deliberate, something that didn’t belong in a child’s hands, and suddenly the sweetness curdled into dread as historians realized this wasn’t innocence… it was a clue 👇

Experts thought this 1910 studio photo was peaceful until they saw what the girl was holding. Dr.Maya Johnson’s hands trembled…

This Portrait from 1895 Holds a Secret Historians Could Never Explain — Until Now It’s Finally Been Exposed in Stunning Detail 🖼️ — For more than a century it hung quietly in dusty archives, dismissed as another stiff Victorian pose, until a routine scan revealed a tiny, impossible detail that made experts freeze mid-sentence, because suddenly the calm expressions looked staged, the shadows suspicious, and the entire image felt less like art… and more like evidence 👇

The fluorescent lights of Carter and Sons estate auctions in Richmond, Virginia, cast harsh shadows across tables piled with forgotten…

It Was Just a Studio Photo — Until Experts Zoomed In and Saw What the Parents Were Hiding in Their Hands, and the Room Went Dead Silent 📸 — At first it looked like another stiff, sepia family portrait, the kind you pass without a second thought, but when historians enhanced the image and spotted the tiny, deliberate objects clutched tight against their palms, the smiles suddenly felt forced, the pose suspicious, and the entire photograph transformed from wholesome keepsake into something deeply unsettling 👇

The auction house in Boston smelled of old paper and varnished wood. Dr.Elizabeth Morgan had spent the better part of…

End of content

No more pages to load