The Overseer Laughed When a Slave Looked Him in the Eye, Until the Man Married His Master’s Daughter

Welcome to this journey through one of the most disturbing cases recorded in the history of the United States.

Before we begin, I invite you to leave in the comments where you are watching from and the exact time at which you are listening to this narration.

We are interested to know which places and at what times of day or night these documented accounts reach.

In the autumn of 1847, the first peculiar report appeared in a small gazette in Virginia.

The article, barely three paragraphs long, mentioned the disappearance of a plantation overseer named Silus Granger.

According to the text, Granger had last been seen riding toward the northern fields of the Carter Plantation, approximately 8 mi from Richmond.

What made this seemingly routine report unusual was the final line, “Mister, Carter reports no concerns regarding the matter as family arrangements have been made to ensure continuity of operations.

For almost 113 years, this brief notice remained buried in county archives until a graduate student named Ellen Morrison discovered it while researching 19th century labor practices in 1960.

What began as a footnote in her dissertation would eventually unravel into one of the most disturbing documented cases of psychological warfare ever recorded in antibbellum America.

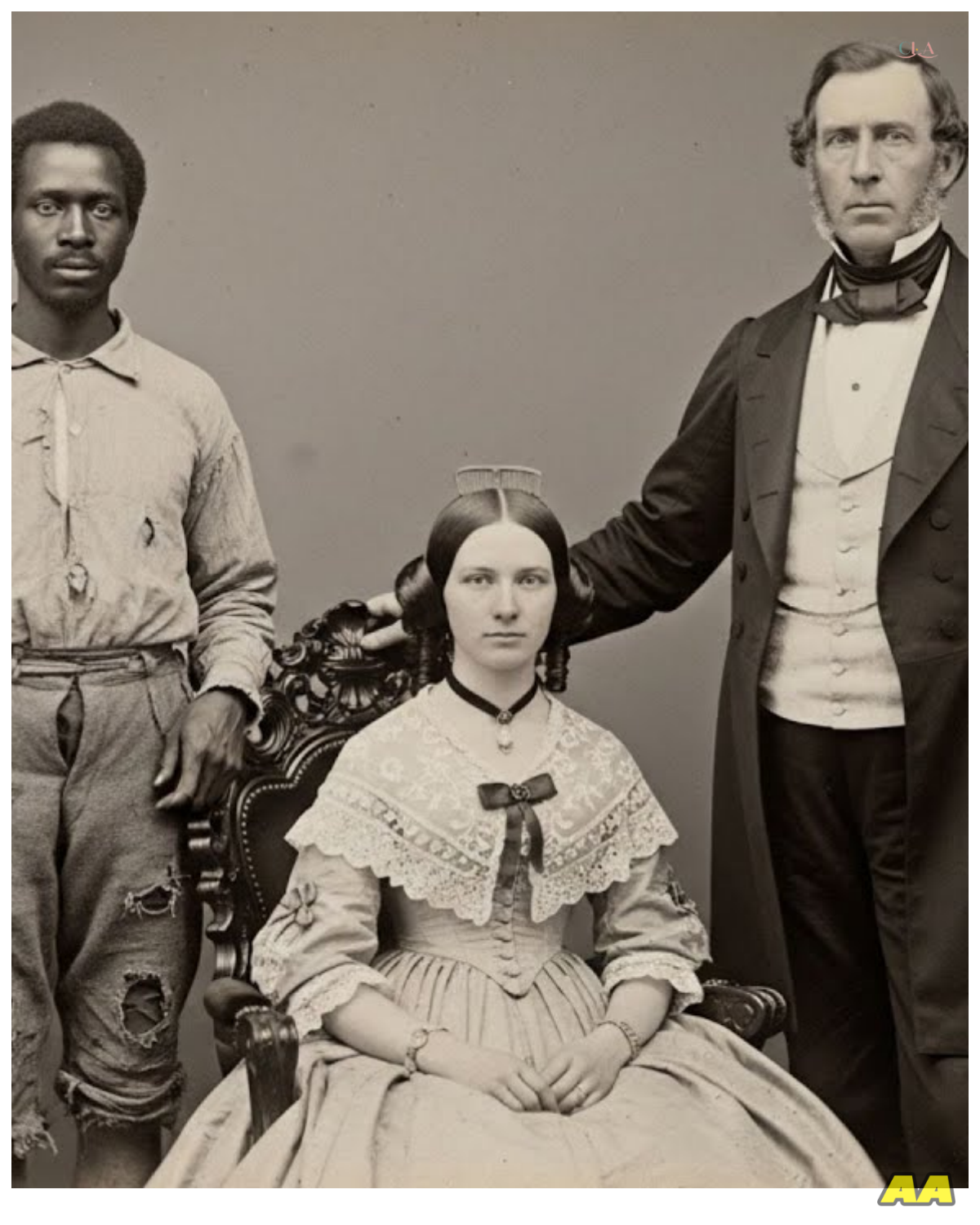

The Carter Plantation, known as Willow Creek, was not particularly remarkable for its time.

Records indicate it encompassed approximately 900 acres primarily dedicated to tobacco cultivation with a modest cotton operation on its eastern boundary.

According to tax documents from 1845, the property housed 73 enslaved individuals, a number that placed it squarely in the middle range of Virginia plantations.

Samuel Carter, the proprietor, had inherited the estate from his father in 1839, and by all accounts maintained its operations without significant change or innovation.

What distinguished Carter from his contemporaries was not the size of his holding or his agricultural methods, but rather his peculiar domestic arrangements.

Parish records indicate that Carter at 31 years of age remained unmarried.

Unusual for a man of his position.

More unusual still was the household census of 1845, which listed only Carter, his daughter Elellanar, aged 17, and three house servants residing in the main dwelling.

No wife was mentioned, nor any record of her death or burial found in church registries.

According to correspondence between Carter and a business associate in Richmond dated February 1846, Elellanena was being prepared for her societal debut the following winter.

The letter mentions expenses related to new gowns, music instruction, and the hiring of a French tutor.

Carter writes, “Though isolated by circumstance, my daughter shall not be denied the refinements due her station.

Providence has seen fit to place certain burdens upon our household.

Yet Elellanena’s prospects remain my foremost consideration.

The nature of these burdens is never explicitly stated, but several sources suggest that Elellanena’s mother may have been institutionalized.

A payment ledger from 1830 shows regular quarterly dispersements to Westbrook Asylum, though the patients name is not specified.

These payments continue without interruption until the first quarter of 1847 when they abruptly cease.

Silas Granger enters the historical record in the spring of 1844 when he was hired as overseer at Willow Creek.

County employment registries describe him as age 30 and 4 years formerly of North Carolina experienced in tobacco cultivation and the management of field hands.

His salary was set at $120 annually with room and board provided, a compensation slightly above the average for his position.

What makes Gringers’s tenure at Willow Creek remarkable is its apparent success.

Production records show a 17% increase in tobacco yield during his first two years, and correspondence between Carter and his factors in Richmond express satisfaction with the quality of the crop.

A letter dated December 1845 notes, Granger has proven a most satisfactory acquisition.

His methods, while occasionally unorthodox, produce results that speak for themselves.

The nature of these unorthodox methods is partially illuminated by an account recorded by a traveling Methodist minister who visited neighboring plantations in 1846.

In his journal, Reverend Thomas Whitfield writes, “I encountered a most troubling situation at a plantation south of Richmond.

The overseer, a man of northern Carolina origin, has instituted what he terms a system of looks, whereby the enslaved are punished not merely for transgressions, but for the manner in which they regard their superiors.

Those who fail to avert their eyes appropriately are subjected to additional labor.

I expressed my concern that such practices foster resentment rather than proper order, but was dismissed by the owner as unfamiliar with the requirements of plantation management.

While Reverend Whitfield does not name the plantation, the geographic description and timing are consistent with Willow Creek during Gringer’s tenure.

This system of controlling even the gaze of the enslaved appears to have been Grers’s innovation, not a common practice in Virginia at that time.

By early 1847, the relationship between Carter and Granger appears to have evolved beyond mere employer and employee.

A notation in Carter’s personal ledger indicates that Granger was invited to dine at the main house on at least six occasions during January and February of that year.

More significantly, an entry dated March 3rd states, “Concluded arrangements with G regarding E’s future terms agreeable to all parties.

Documentation to follow upon completion of spring planting.

What these arrangements entailed is not explicitly stated, but contextual evidence suggests that Carter may have been considering Granger as a potential son-in-law.

This would have represented a significant social step up for Granger, whose background, while respectable, was decidedly common.

For Elellanena Carter, however, such a match would have been considered beneath her station.

The household ledger for April 1847 shows an unusual expenditure.

Silver cufflinks and watch fob for SG, $12.

This gift substantial for the period further suggests that Granger was being elevated within the household hierarchy.

Concurrently, Elellanena’s diary recovered in a collection of Carter Family Papers donated to the Virginia Historical Society in 1952 makes several references to dining with Father and Mister G.

Though her assessment of these interactions is frustratingly oblique, she notes only that father seems increasingly satisfied with our arrangement, though I find the situation curious in the extreme.

It is at this juncture that the narrative takes its first dark turn.

A plantation inventory dated April 27th, 1847, lists among the field workers a man identified only as Isaiah, aged 20 and 8 years, acquired from Fairfax Estate Settlement value $800.

This entry is remarkable for two reasons.

First, it represents the only acquisition of an enslaved person by Carter that year.

Second, subsequent events suggest that this individual would become central to the events that followed.

According to a journal kept by Willow Creek’s housekeeper Sarah Miller, discovered among her descendants effects in 1957, Isaiah was initially assigned to tobacco cultivation, but was reassigned to the stables after less than 2 weeks.

Miller writes, “Mr.

Granger came to dinner in a state of agitation I have not previously observed.

He spoke at length to Master Carter regarding the new field hand, who he claims refuses to observe proper conduct.

Master Carter suggested reassignment to the stables where closer supervision might be maintained.

Miller’s journal, which covers the period from January 1847 to August 1848, provides one of the few contemporaneous accounts of daily life at Willow Creek.

As a free white woman employed in a position of relative responsibility, she occupied a unique vantage point, neither family nor enslaved, but privy to the workings of both worlds.

Her entry for May 7th contains a particularly revealing passage.

Mr.

Granger complained again regarding Isaiah’s comportment.

It seems the man persists in meeting his gaze directly, a behavior Mr.

Granger considers deliberately provocative.

Master Carter advised patience, noting that the man’s previous employment on a Quaker owned property may have instilled improper notions regarding his station.

Mister Granger appeared unsatisfied with this explanation, but conceded to Master Carter’s authority in the matter.

This reference to Isaiah’s previous employment provides a critical piece of context.

The Fairfax estate from which Isaiah had been purchased had indeed been owned by a Quaker family until the death of its proprietor in late 1846.

While not abolitionists in practice, the Quakers were known for their somewhat more humane treatment of enslaved persons.

An individual transitioning from such an environment to Grers’s system of looks would indeed have found the adjustment jarring.

The situation appears to have deteriorated throughout May and June.

Miller’s journal records multiple instances of conflict between Granger and Isaiah, culminating in a disturbing entry dated June 23rd.

Commotion in the yard this afternoon.

Isaiah was observed speaking with Miss Elellanena near the kitchen garden.

Mr.

Granger, upon witnessing this exchange, ordered Isaiah to the tool shed for discipline.

Master Carter unusually countermanded this order and directed Isaiah to continue his stable duties.

Words were exchanged between Master and Mr.

Granger that I could not hear clearly, but their expressions suggested significant disagreement.

Elellanena’s diary provides additional context for this incident.

Her entry for the same day reads, “I encountered Father’s new stable hand while gathering herbs for Mrs.

Miller.

The man spoke with unusual refinement, informing me that certain plants I was collecting might be mistaken for their poisonous counterparts.

When I inquired as to his knowledge of bot, he mentioned educational opportunities afforded by his previous owners.

Our conversation was interrupted by Mr.

Granger, whose reaction seemed disproportionate to the situation.

Father later assured me that the man would not be punished for his helpful intervention.

This entry suggests that Isaiah possessed education unusual for an enslaved person, which may have further complicated his relationship with Granger.

The reference to educational opportunities at his previous placement aligns with known Quaker practices of occasionally permitting limited literacy among enslaved individuals, particularly those serving in specialized roles.

The following weeks show an escalation in tensions.

Miller reports that Granger began taking his meals separately from the family, while Carter spent increasing amounts of time in the stables, ostensibly inspecting the horses, but engaging in lengthy conversations with Isaiah.

Meanwhile, Elellanena’s diary records a growing interest in horsemanship, with daily riding lessons supervised not by Granger, as would have been customary, but by I, whose gentle instruction has improved my seat considerably.

By mid July, Granger’s position appears to have been increasingly undermined.

A letter from Carter to his Richmond factor, dated July 17th, notes, “Regarding your inquiry about Mr.

Granger’s authority to negotiate the tobacco sale.

Please be advised that all final decisions rest with me.

Recent events have necessitated a clarification of responsibilities on the estate.

Concurrently, Isaiah’s position seems to have been elevated.

The household expense ledger shows the unusual purchase of proper attire for stable master, suggesting a promotion from ordinary stable hand to a position of greater responsibility.

This rapid advancement would have been exceptional for any servant, let alone an enslaved individual recently acquired and with a history of problematic interactions with the overseer.

The most revealing document from this period is a letter discovered in 1958 among the papers of Judge William Hawthorne of Richmond dated July 25th, 1847.

It is addressed from Samuel Carter and inquires about the legal requirements for manumission of an enslaved individual with subsequent employment as a free person.

The letter specifically asks whether such an arrangement would require public notification or could be handled discreetly.

Judge Hawthorne’s response, dated August 3rd, outlines the legal procedure, but cautions that such actions invariably attract notice regardless of attempts at discretion.

This exchange suggests that Carter was contemplating Isaiah’s emancipation approximately 3 months after his purchase.

An extraordinary development that points to some larger design.

Carter’s concern with discretion indicates awareness that his intentions might prove controversial.

Events accelerated dramatically in August.

Miller’s journal entry for August 12th states, “Miss Elellanena confined to her room with what Master Carter describes as a nervous complaint.

Dr.

Reynolds summoned from Richmond but departed without providing treatment following private consultation with Master Carter.

The household is unsettled by these developments.

Elellanena’s diary provides no illumination.

The pages for early August have been removed with only the ragged edge of torn paper remaining.

When her entries resume on August 21st, they are remarkably circumspect, discussing only the weather and her reading materials.

The only potential reference to her nervous complaint is an oblique mention that father assures me that all arrangements proceed according to plan and I must trust in his judgment during this difficult interval.

The most dramatic evidence from this period comes from an unexpected source.

A letter written by Silas Granger to his brother in North Carolina, intercepted by Carter and never sent, but preserved among the Carter papers.

Dated August 15th, the letter contains the following passage.

The situation at Willow Creek has become untenable.

Carter has taken leave of his senses, allowing the stable hand to dine at his table while I am relegated to taking meals in my quarters.

Worse, I have twice observed Eleanor in the man’s company, once walking in the garden, and once in the library, apparently engaged in reading.

When I brought these improprieties to Carter’s attention, he informed me that my services would soon be unnecessary, as new arrangements were being made for the plantation’s management.

I have invested three years in this position with the understanding that more significant compensation would eventually be forthcoming.

To be supplanted by a field hand, regardless of his affected refinement, is beyond endurance.

I intend to confront Carter directly and demand clarification of my position.

This letter provides the clearest indication of the dramatic reversal occurring at Willow Creek.

Isaiah, purchased as a field hand just 4 months earlier, was now apparently being integrated into the household, while Granger, once considered for elevation to the family, was being marginalized.

The confrontation Granger intended apparently took place on or around August 20th.

Miller’s journal records raised voices from Master Carter’s study this evening.

Mr.

Granger departed in evident agitation, riding north despite the late hour.

Master Carter instructed that no one should follow.

This is the last confirmed sighting of Silus Granger at Willow Creek.

The plantation’s payment ledger shows that his salary was paid in full through August with the notation contract terminated by mutual agreement.

No further record of Gringanger appears in Carter’s documents.

The notice in the local gazette mentioned at the beginning of this account appeared on September 7th, 1847.

Its casual tone and reference to family arrangements for continuing operations takes on new significance in light of the documents described above.

What followed was perhaps even more extraordinary than Grers’s disappearance.

On September 28th, the parish register of St.

Paul’s Church in Richmond records the baptism of Isaiah Freeman, formerly of the Carter estate, now a free man of color.

The sponsor listed for this baptism is Samuel Carter himself.

The choice of surname Freeman makes the circumstances of this event unmistakable.

Isaiah had been emancipated.

More remarkable still is a deed recorded in the Richmond County offices dated October 3rd, 1847.

This document transfers ownership of a small property, 30 acres with a modest house from Samuel Carter to Isaiah Freeman for the sum of $5.

Such a nominal payment indicates a gift rather than a genuine sale, effectively establishing the newly freed Isaiah as a landowner, an exceedingly rare status for a black man in Virginia at that time.

The events that followed are documented in Elellanena Carter’s resumed diary entries and in Miller’s increasingly astonished journal.

Throughout October and November, Isaiah Freeman was a regular visitor to Willow Creek, ostensibly to assist with the fall harvest as a paid laborer.

Miller notes that he took meals with the family and was treated with a degree of respect that caused considerable comment among both the white staff and the enslaved community.

Eleanor’s diary entries from this period reveal a growing attachment to Isaiah, though expressed in carefully measured terms.

She writes on November 12th, “I and father engaged in lengthy discussion of agricultural improvements following dinner.

I proposed methods of crop rotation he observed in Pennsylvania that father found most intriguing.

His knowledge extends well beyond what one might expect, and his articulation of complex ideas demonstrates an exceptional mind.

Father appears increasingly satisfied with our arrangement.

The nature of this arrangement becomes clear in a letter from Carter to Judge Hawthorne dated December 5th, which states, “Having considered all aspects of the situation, including potential social and legal complications, I remain resolved to proceed as discussed.

E is fully informed and consenting.

The ceremony will be conducted privately with documentation to follow.

I anticipate relocating to the Richmond townhouse thereafter, leaving rural matters in capable hands.

What Carter was proposing was nothing less than a marriage between his daughter Elellanena and Isaiah Freeman, a union that, while not explicitly prohibited by Virginia law at that time, would have been socially unthinkable.

The fact that Isaiah had been enslaved on Carter’s own plantation just months earlier made the arrangement all the more extraordinary.

The ceremony apparently took place on December 20th, 1847.

No church record exists, suggesting it was conducted privately, perhaps by a minister brought in from outside the community.

Miller’s journal entry for that day states only, “The event proceeded as planned.

Master Carter, Miss Elellanena, and Mr.

Freeman departed for Richmond immediately thereafter.

I am to follow with selected household items once the inventory is complete.

This marks the effective end of Willow Creek as a functioning plantation under Carter ownership.

A notice in the Richmond Business Register of January 1848 indicates that the property was leased to a neighboring planter with operations to be consolidated.

The enslaved community was not sold off in a single auction as was common practice when plantations changed hands.

Instead, county records show that 23 individuals were emancipated through proper legal channels over the next 6 months, while others were relocated to the properties of relatives or neighboring planters.

Within a year, Willow Creek had effectively ceased to exist as an independent entity.

The fate of Samuel Carter, Elellanena, and Isaiah is less clearly documented after their departure from Willow Creek.

Richmond property records confirm Carter’s ownership of a townhouse on Adam Street, where tax documents suggest a household of three resided until 1852.

Church records indicate that Samuel Carter died in February of that year and was interred in the family plot.

What became of Elellanena and Isaiah after Carter’s death requires speculation based on fragmentaryary evidence.

A passenger manifest from the port of Boston dated April 1852 lists I.

Freeman and wife among those departing for Liverpool.

Immigration records from England later that year include an Isaiah and Elellanena Freeman of American origin taking up residence in a small village outside Manchester.

The final piece of documentation comes from an unexpected source.

In 1959, a researcher at the University of Manchester discovered a series of articles in a local newspaper dated 1863 through 1870.

These pieces on agricultural improvements were authored by an I.

Freeman, formerly of Virginia.

The author is described in an editorial note as a gentleman farmer of mixed heritage whose innovative methods have been adopted by several prominent estates in the region.

This suggests that Isaiah and Elellanena not only escaped the escalating tensions of pre-ivil war America, but established themselves successfully abroad, where the social barriers to their union may have been somewhat less rigid.

No record has been found of any children from their marriage.

The fate of Silas Granger remains officially unresolved.

No body was ever recovered.

No subsequent trace of him discovered in public records.

His disappearance coincided with a period of significant change at Willow Creek, including the elevation of an enslaved man to free status, landowner, and ultimately son-in-law to the plantation owner.

The most disturbing possibility that Grers’s disappearance was not voluntary is suggested by a single ambiguous entry in Elellanena’s diary dated September 1st, 1847.

The matter with Mr.

G has been resolved to father’s satisfaction, I assures me that no evidence remains to trouble us.

The Northfield will yield an exceptional crop next season, he says, due to the enrichment of the soil.

This cryptic reference is the only potential indication of foul play, though it falls far short of evidence that would have warranted investigation.

The North Field, where Granger was reportedly last seen, was indeed harvested and replanted without incident the following spring.

In 1968, during construction of a highway that crossed a portion of the former Willow Creek property, workers uncovered human remains approximately 6 ft below the surface of what had once been the plantation’s northern tobacco field.

The bones, determined to be those of a white male in his 30s, showed evidence of blunt force trauma to the skull.

Due to the age of the remains and the extensive development of the area, no further investigation was pursued.

The bones were documented by the county medical examiner and subsequently reinterred in an unmarked grave in the Richmond public cemetery.

The coroner’s report filed away and forgotten for decades noted one unusual feature.

green staining on right metacarpals consistent with prolonged contact with copper alloy possibly from a ring or similar ornament.

Historical records indicate that Silus Granger was known to wear a copper ring inherited from his father.

The events at Willow Creek Plantation in 1847 represent a remarkable inversion of established power structures in Antibellum, Virginia.

A man purchased as property rose to become a landowner and legal family member within a matter of months while his overseer once positioned for that same elevation vanished under circumstances that remain officially unresolved.

What prompted Samuel Carter to take actions so dramatically contrary to the social norms of his time and place? The most compelling theory supported by the timing of events involves the sessation of payments to Westbrook Asylum in early 1847, the same period when Isaiah was purchased and the dynamic at Willow Creek began to shift.

If, as circumstantial evidence suggests, these payments had been maintaining Elellanena’s mother in confinement, her death would have removed a significant constraint on Carter’s actions.

Some researchers have speculated that Carter, faced with his own mortality and lacking male heirs, made a calculated decision to secure his daughter’s future through an unconventional alliance with a man whose intelligence and capabilities he had come to respect.

The rapid sequence of Isaiah’s purchase, elevation, emancipation, and marriage to Elellanena suggests a plan executed with deliberate speed, perhaps due to Carter’s awareness of his own declining health.

Whatever the motivation, the documented events at Willow Creek stand as a remarkable anomaly in the history of plantation society.

A rare instance where the rigid hierarchies of race and status were not merely challenged, but deliberately dismantled by a member of the planter class himself.

As for Isaiah and Eleanor, their apparent escape to England and successful establishment there represents an extraordinary conclusion to an already remarkable narrative that a man who began 1847 as newly purchased property ended that same year as a free landowner and within 5 years had established himself as a respected agricultural innovator in another country defies the conventional understanding of opportunities available.

to enslaved individuals in the antibbellum south.

The story of Willow Creek has been preserved primarily through documents never intended for public consumption, private diaries, household ledgers, personal correspondence rather than through official histories.

This may explain why it remained obscured for over a century before Ellen Morrison’s fortuitous discovery in 1960 brought it to light.

What remains unknown and perhaps unknowable is the true fate of Silus Granger.

The remains discovered in 1968 provide tantalizing but inconclusive evidence.

If the overseer who once laughed at an enslaved man’s direct gaze did indeed end his days buried in the north field of Willow Creek, it represents a final grim inversion of the power dynamic he had so rigorously enforced.

The case of Willow Creek Plantation serves as a stark reminder that the historical record, even of relatively recent periods, contains gaps and silences that may conceal extraordinary narratives of resistance, subversion, and the occasional remarkable triumph over seemingly immutable systems of oppression.

To this day, visitors to the highway rest stop constructed near the former Northfield of Willow Creek report an unusual atmosphere, a heaviness in the air that some attribute to ordinary humidity, but others describe as the weight of unresolved history.

Local legend holds that on particularly still nights, the sound of laughter can sometimes be heard.

Not joyful laughter, but the nervous, uncertain laughter of a man who has suddenly realized that his position of power was far more tenuous than he had ever imagined.

In the spring of 1963, Ellen Morrison, whose graduate research had first unearthed the Willow Creek story, returned to Virginia to continue her investigation.

Now a professor at Barnard College, Morrison had spent the intervening years collecting scattered references to the Carter family and Isaiah Freeman.

Her discoveries documented in a monograph published by the University of Virginia Press in 1965 add several significant dimensions to the narrative.

Most compelling among these findings was a series of letters exchanged between Samuel Carter and his cousin William Carter, a merchant based in Philadelphia.

These letters, preserved in the William Carter Business Archives at the Pennsylvania Historical Society, reveal crucial context about Samuel Carter’s motivations and the circumstances surrounding Isaiah’s elevation.

In a letter dated March 18th, 1847, less than a month after Isaiah’s purchase, Samuel writes, “The individual of whom I inquired has arrived at Willow Creek.

Your information regarding his character and capabilities proved accurate in all respects.

He presents himself with remarkable dignity despite his circumstances, and his literacy exceeds my expectations.

I believe he may indeed be suited for the purpose we discussed, provided matters can be arranged discreetly.

William’s response, dated April 2nd, advises caution.

While I appreciate your determination to secure E’s future through unconventional means, I urge restraint in executing your design.

The man’s qualities, however exceptional, cannot overcome the social barriers that would confront such an arrangement.

Consider instead my earlier proposal regarding my colleague’s son, who would bring both acceptable lineage and financial security.

This exchange suggests that Samuel Carter’s plan to elevate Isaiah was formed almost immediately upon his arrival at Willow Creek, and that this plan was connected to securing Elellanena’s future, seemingly confirming the theory that Carter was deliberately seeking a husband for his daughter, who possessed specific qualities regardless of social convention.

More surprising is the implication that Isaiah’s purchase was not random, but targeted based on information provided by William Carter in Philadelphia.

This raises the intriguing possibility that Isaiah had been identified and selected for his role before ever arriving at Willow Creek.

A subsequent letter from Samuel to William dated May 12th provides additional insight.

Your concerns regarding social consequences are duly noted, but ultimately irrelevant to my purpose.

His condition, as you well know, precludes a conventional match.

No family of standing would entertain such a connection once the circumstances became known.

Better a man of excellent qualities but unfortunate station than perpetual isolation.

As for G, his expectations were always presumptuous.

The occasional dinner invitation does not constitute a promise despite his evident assumptions.

This reference to Eleanor’s condition introduces a new element to the narrative.

What condition might have made her unsuitable for a conventional marriage in Virginia society? Morrison’s research uncovered a potential answer in medical records from Westbrook Asylum which contain an admission document for Katherine Carter, wife of Samuel in 1830.

The diagnosis listed is hereditary melancholia with episodes of violent agitation with a notation that the condition manifested similarly in her mother.

If Elellanena was believed to have inherited her mother’s mental condition, this might indeed have made her a problematic match in a society obsessed with bloodlines and heredity.

Samuel’s determination to secure a husband for her, who would be dependent on his patronage rather than a man from their own social circle who might eventually institutionalize her as he had her mother, takes on a new dimension of paternal protection.

Morrison’s most significant discovery, however, came through her persistent efforts to trace Isaiah’s origins before his purchase by Carter.

Tax records from the Fairfax estate confirmed that he had indeed been held there, but only for approximately 6 months following the death of the property’s Quaker owner.

Prior to that, his trail seemed to disappear.

The breakthrough came from an unexpected source, the records of a small Quaker school in Pennsylvania, where an entry from 1839 mentions Isaiah, a freeman of color from Maryland, employed as assistant to the groundskeeper and permitted to attend evening lessons in recognition of his exceptional aptitude.

This suggests that Isaiah had once been free, receiving education in a northern state before somehow being reinsslaved and transported south.

Such cases, while not common, did occur in the chaotic legal landscape of antibbellum America, where free black individuals were vulnerable to kidnapping and fraudulent enslavement.

Further investigation of Pennsylvania court records revealed an even more startling possibility.

In 1841, a case was brought before the Philadelphia Court of Common Please regarding Isaiah Freeman, a free man of color allegedly abducted and transported south under false pretenses.

The plaintiff listed as William Carter merchant acting as concerned party claimed that Freeman had been seized while traveling on business between Philadelphia and Baltimore, then sold to traders bound for Virginia.

The case was ultimately dismissed due to lack of jurisdiction and the inability to locate the alleged victim.

However, the involvement of William Carter, Samuel’s cousin and correspondent, creates a compelling connection.

If the Isaiah Freeman of this court case was the same man who would later be purchased by Samuel Carter from the Fairfax estate, it suggests an elaborate yearslong effort by the Carter cousins to locate and recover a specific individual.

This possibility is strengthened by a cryptic passage in one of William’s letters to Samuel dated February 1847.

The individual about whom you have inquired these six years past has been located at last.

He is held at the estate previously mentioned, though now under new ownership following the proprietor’s death.

His asking price is considerable, but I have made discreet inquiries and believe he maintains the qualities that first brought him to our attention, despite the unfortunate interruption to his circumstances.

If you wish to proceed, arrangements can be made without delay.

The implication is extraordinary.

Samuel Carter may have purchased Isaiah not simply as plantation labor, but as part of a long planned rescue and restoration of a man who had been wrongfully enslaved, a man who, based on the Philadelphia court records, had once lived as Isaiah Freeman, the very name he would reclaim after his emancipation by Carter.

If true, this adds new dimensions to the relationship between Carter, Isaiah, and Granger.

The overseer’s increasing marginalization would not have been simply the result of being supplanted in Carter’s favor, but part of a predetermined plan in which Granger was never intended to be more than a temporary placeholder.

The final pieces of Morrison’s research concerned the fate of Isaiah and Eleanor after their departure from the United States.

British census records from 1861 confirm that Isaiah Freeman, age 42, agricultural consultant, and Elellanena Freeman, aged 33, were indeed residing in the village of Thornfield outside Manchester.

The household also included a child, Samuel Freeman, age 8, born Jamaica.

This Jamaican birth suggests that Isaiah and Elellanena may have spent time in the Caribbean before settling in England, perhaps to establish their family away from the scrutiny of either American or British society.

The choice to name their son after Elellanena’s father indicates a desire to maintain connection with the man who had made their union possible.

A death notice in the Manchester Guardian from 1876 reports the passing of Isaiah Freeman, noted agricultural innovator formerly of the United States and Jamaica, survived by his wife Elellanar and son Samuel.

Elellanena’s death is recorded 15 years later in 1891.

By then, according to local church records, Samuel Freeman had married an English woman and fathered two children of his own.

What becomes evident through Morrison’s research is that the story of Willow Creek, Isaiah, and Eleanor represents not just an anomalous subversion of antibbellum power structures, but potentially a decadesl long effort by Samuel and William Carter to write a specific wrong, the kidnapping and enslavement of a free man, while simultaneously securing Elellanena’s future through an unconventional but carefully selected match.

The role of Silas Granger in this narrative takes on new significance as well.

If Samuel Carter had already identified Isaiah as his intended son-in-law before purchasing him, then Granger’s position, despite any impressions he may have formed from dining invitations or gifts, was always temporary.

His enforcement of the system of looks, requiring enslaved people to avert their eyes, becomes particularly ironic, given that Isaiah’s direct gaze, his refusal to perform expected difference, was likely one of the qualities that had impressed Carter and confirmed Isaiah’s suitability for the role Carter had in mind.

The fate of Silus Granger remains the darkest element of the Willow Creek story.

The human remains discovered in 1968 were never definitively identified, and the case was officially closed without resolution.

However, in 1966, an elderly woman named Martha Collins, claiming to be the granddaughter of Sarah Miller, the Willow Creek housekeeper, whose journal provided crucial documentation, approached Morrison with what she described as family knowledge regarding Grers’s disappearance.

According to Collins, her grandmother had confided that on the night Granger vanished, she had observed Samuel Carter, Isaiah, and two other men she did not recognize loading a heavy trunk onto a wagon shortly before midnight.

The wagon departed toward the North Field and returned empty approximately 2 hours later.

Miller never reported this observation to authorities, but documented it in a separate journal kept locked in her personal chest, a journal that did not survive into the modern era.

If this account is accurate, it suggests that Grers’s disappearance was indeed orchestrated by Carter and Isaiah, potentially with assistance from outside accompllices.

This would transform the narrative from one of social subversion to something considerably darker, deliberate homicide as part of a complex plan to eliminate an obstacle and reconfigure the power structure of Willow Creek Plantation.

Morrison’s monograph presents these findings with appropriate scholarly caution, acknowledging the fragmentaryary nature of the evidence and the significant gaps that remain in the historical record.

However, the documents she uncovered, particularly the correspondence between the Carter cousins and the Philadelphia court records, provide compelling support for a revised understanding of the Willow Creek events.

In the decades since Morrison’s work, the Willow Creek narrative has attracted attention from historians specializing in antibbellum America, race relations, and the complexities of plantation society.

Some scholars have questioned aspects of Morrison’s interpretation, suggesting alternative readings of the documentation or challenging the identification of the Philadelphia court cases Isaiah Freeman with the man who would later marry Elellanena Carter.

Yet the basic contours of the narrative remain intact.

A plantation overseer who enforced rigid racial hierarchies disappeared under mysterious circumstances, while an enslaved man rose with unprecedented speed to become a free landowner and the son-in-law of his former owner.

Whatever the precise motivations and minations behind these events, they represent an extraordinary disruption of the social order that defined the antibbellum south.

The site of Willow Creek Plantation is now largely covered by suburban development with only a small historical marker noting its existence and significance.

The north field where Granger was last seen and where human remains were discovered in 1968 lies beneath the eastbound lanes of Interstate 64.

Thousands of travelers pass over it daily, unaware of the ground’s grim history.

Local folklore has preserved elements of the Willow Creek story in distorted form.

Residents of the area sometimes speak of Grers’s laugh, a high-pitched sound supposedly heard near the highway at night, described as a nervous laugh that turns to something else.

Some versions of the legend claim that anyone who hears this sound will experience a reversal of fortune within the year.

What was high will be brought low.

what was low will rise.

Historians tend to dismiss such folklore as typical supernatural accretions to historical events, noting that the transformation of Granger from victim to spectral harbinger of reversed fortunes reflects the human tendency to extract moral meaning from ambiguous circumstances.

Yet the persistence of these stories speaks to the profound unease generated by the Willow Creek narrative, a sense that established orders, no matter how rigid they appear, may contain the seeds of their own subversion.

In 2002, ground penetrating radar surveys were conducted along the margins of Interstate 64 as part of a highway expansion project.

These surveys detected several anomalies consistent with human burials in what would have been the northwestern section of the Willow Creek property.

Due to construction timelines and budget constraints, these anomalies were documented but not investigated further.

The official report noted only that historical records indicate the possible presence of unmarked burials associated with the former plantation property with a recommendation that any future development in the area should include archaeological assessment.

These potential graves, their occupants unidentified and their stories untold, serve as a final mute testament to the human costs of the system that Willow Creek both exemplified and in its final chapter momentarily subverted.

In the end, the story of Silas Granger, Isaiah Freeman, and the Carters of Willow Creek remains incomplete like so many narratives extracted from the historical record.

What documents survive suggest an extraordinary sequence of events, a deliberate inversion of established hierarchies orchestrated by a plantation owner for reasons that combined practical necessity, paternal concern, and possibly a desire to correct a specific injustice.

For Isaiah and Elellanena, the outcome appears to have been a successful escape from the constraints of American society to build a life abroad.

a rare instance of something approaching a happy ending, emerging from the brutal context of plantation slavery.

For Silus Granger, if the remains discovered in 1968 were indeed his, the story ended in the Northfield where he was last seen, buried beneath the crop he had once supervised.

The most unsettling aspect of the Willow Creek narrative may be what it suggests about power and its exercise in human societies.

Systems that appear immutable, enforced through violence, sanctified by law and custom, can sometimes be undone with surprising ease when those who benefit from them choose to withdraw their participation.

Samuel Carter, through his position and privilege, was able to dismantle on his own property the very system that granted him his authority, elevating the enslaved and eliminating the enforcer, all while maintaining sufficient appearances to avoid outside intervention.

This suggests a disturbing flexibility to even the most rigid social structures, not because they are vulnerable to collective resistance, though they may be, but because their continuation depends on the momentto- moment compliance of those with power.

The overseer laughed when a slave looked him in the eye, secure in his position within the hierarchy.

Months later, he was gone, and the man he had mocked sat at the master’s table, courting the master’s daughter.

Perhaps this is why the Willow Creek story continues to unsettle.

It suggests that the orders we perceive as fixed and natural, may be more contingent than we care to admit, maintained not by their inherent rightness or inevitability, but by thousands of individual decisions to comply with expected patterns of behavior.

And if such orders can be unmade by the deliberate action of those within them, then none of us can be entirely certain of where we stand or for how long.

Visitors to the highway rest stop near the former Willow Creek property, often report feeling a strange tension in the air.

Not supernatural exactly, but a sense of standing at a juncture where established patterns were broken and new possibilities, both liberating and terrifying, emerged.

Some say they feel watched as though someone is waiting to see what they will make of this knowledge, what small rebellions or compliances they will enact in their own lives.

And sometimes in the stillness between passing cars, there comes a sound that might be the wind through the remaining trees or might be something else.

Something that begins as laughter and ends as a cry of belated recognition, echoing across fields that have long since been paved over, but still hold their secrets, waiting for those with the courage to unearth them.

News

✈️ U.S. F-15 FIRST STRIKE — ALLEGED CARTEL DRUG LAB ERASED IN SECONDS AS SKY ERUPTS IN A BLINDING FLASH ✈️ What officials described as a precision operation turned the night into daylight, with jets screaming overhead and a suspected production site reduced to smoking rubble in moments, sending a shockwave across the region and a message that the airspace above is no safe haven for hidden empires 👇

The Last Fortress: A Shocking Revelation In the heart of the Mexican jungle, Diego stood at the entrance of the…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: FBI & ICE SHATTER ALLEGED TRUCKING NETWORK WITH SOMALI TIES — 83 ARRESTED, $85M IN CASH AND WEAPONS STACKED AS EVIDENCE 🚨 Before sunrise, federal agents swept through depots and dispatch offices, hauling out duffel bags of currency and seizing firearms while stunned neighbors watched a logistics operation authorities claim was hiding a sprawling criminal enterprise behind everyday freight routes 👇

The Shadows of the Ghost Fleet In the heart of the Midwest, where the snow fell like a blanket over…

🚨 FBI & ICE STORM GEORGIA “CARTEL HIDEOUT” — GRENADE LAUNCHER DISCOVERED AND $900K IN DRUGS SEIZED IN A DAWN RAID THAT SHOCKED THE BLOCK 🚨 What neighbors thought was just another quiet morning exploded into flashing lights and tactical vests as agents swept the property, hauling out weapons and evidence while officials described a months-long investigation that culminated in a swift, coordinated takedown 👇

The Unraveling of Shadows: A Tale of Betrayal and Redemption In the heart of Jackson County, Georgia, the air was…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: DEA & FBI CRUSH ALLEGED CARTEL TRUCKING EMPIRE — HIDDEN ROUTES MAPPED, DRIVERS DETAINED, AND MILLIONS STACKED AS EVIDENCE 🚨 Before sunrise, highways turned into a grid of flashing lights as agents intercepted rigs, cracked open trailers, and traced coded dispatch logs, revealing what officials describe as a logistics web hiding in plain sight behind ordinary freight lanes 👇

The Fall of Shadows: A Cartel’s Empire Exposed In the dimly lit corridors of power, where shadows danced with deceit,…

🚢 U.S. NAVY TRAPS SINALOA CARTEL’S ALLEGED $473 MILLION “DRUG ARMADA” AT SEA — AND THE HIGH-STAKES STANDOFF UNFOLDS UNDER FLOODLIGHTS AND ROTOR WASH 🚢 Radar screens lit up, cutters boxed in fast boats, and boarding teams moved with clockwork precision as authorities described a sweeping maritime interdiction that turned open water into a chessboard, stacking seized cargo on deck while prosecutors hinted the ripples would travel far beyond the horizon 👇

The Abyss of Deceit: A Naval Reckoning In the heart of the Caribbean, where the turquoise waters glimmered under the…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: DEA & FBI DESCEND ON MASSIVE TEXAS LOGISTICS HUB — 52 TONS OF METH SEIZED AS 20 POLITICIANS ALLEGEDLY TIED TO A SHADOW NETWORK ARE THRUST INTO THE SPOTLIGHT 🚨 What began as a quiet federal probe detonated into a sweeping raid of warehouses and boardrooms, with agents hauling out towering stacks of evidence while stunned insiders whisper that the real shockwave isn’t just the drugs — it’s the powerful names now facing intense scrutiny 👇

Shadows of the Underground: The Texas Cartel Unveiled In the heart of Texas, where the sun sets over sprawling landscapes,…

End of content

No more pages to load