The Most Horrifying Slave Mystery in Mobile History (1842)

Welcome to this journey through one of the most disturbing cases recorded in the history of Mobile Alabama.

Before we begin, I invite you to leave in the comments where you are watching from and the exact time at which you are listening to this narration.

We are interested in knowing to which places and at what times of day or night these documented accounts reach.

Mobile, Alabama.

The Caldwell estate sat 3 mi outside Mobile city limits nestled among cypress trees draped with Spanish moss.

The property was easily identified by its distinctive row of 12 oak trees lining the halfmile approach to the main house.

In 1842, the estate belonged to Thomas Caldwell, a man of considerable means whose family had relocated from Virginia some 20 years prior.

The Caldwell name carried weight in Alabama society circles, though some whispered that old Thomas had been more ruthless than most in amassing his fortune.

What happened on that property in the autumn of 1842 would be spoken about in hush tones for decades to come, then gradually fade into obscurity, buried beneath newer tragedies and the collective amnesia that sometimes seems to protect small communities from their darkest memories.

According to county records, the Caldwell plantation employed 38 enslaved individuals, though unofficial accounts suggest the number may have been considerably higher.

Among them was a man named Isaac.

His last name, Caldwell, was not his by birth, but assigned to him, as was common practice.

The documents regarding Isaac are frustratingly sparse, consisting primarily of property listings, and a single notation in a ledger book recovered from the estate overseer’s quarters in 1958.

The notation dated March 3rd, 1842 reads simply, “I moved to North Fields.

” Replacement needed.

This seemingly mundane administrative note would later take on a more ominous significance when pieced together with other fragments of the story.

The other name in our narrative belongs to Rebecca Fontaine, the widowed sister of Thomas Caldwell’s wife, Elizabeth.

Rebecca had arrived from Charleston in the spring of 1841 following the untimely death of her husband James Fontaine, a shipping merchant whose business had fallen into decline in the years preceding his passing.

Local gossip documented in the diary of Margaret Hulkcom, a neighbor who lived a mile east of the Caldwell property, suggested that Rebecca’s arrival was not entirely welcomed by her brother-in-law.

Mrs.

C mentioned today that Mr.

C has been in poor spirits since the arrival of her sister, reads an entry dated July 18th, 1841.

He complains of additional expense and disruption to household affairs.

Mrs.

F apparently keeps to herself mostly, occupying the east wing rooms and taking meals separately from the family on most days.

The east wing of the Caldwell House overlooked a section of the property that had once been cultivated, but had been allowed to grow wild in the years before Rebecca’s arrival.

According to property maps filed with the Mobile County clerk’s office in 1839, this area was designated as land unsuitable for further cultivation.

No explanation for this designation was provided, though soil samples taken during an agricultural survey conducted by Mobile University in 1963 revealed unusually high concentrations of iron and sulfur in this precise location.

The study’s authors noted this as an anomaly, but offered no historical context for their findings.

The events that unfolded on the Caldwell estate began to take shape in the late summer of 1842.

August of that year was marked by unseasonably heavy rains that saturated the Alabama soil and caused the Alabama River to swell beyond its banks in some areas.

According to meteorological records preserved by the mobile harbor master, August of 1842 saw 23 days of rainfall compared to the average of nine for that month.

The persistent dampness created problems throughout the region, including an outbreak of fever that claimed 17 lives in Mobile proper and an undetermined number in the surrounding rural areas.

It was during this period of atmospheric gloom that the first unusual occurrences were noted at the Caldwell property.

Elizabeth Caldwell’s personal diary, discovered in 1957 during the renovation of what had once been the estate’s main house, contains the first reference to what would become a pattern.

On August 22nd, she wrote, “The rain continues without mercy.

Thomas has been irritable with the field hands due to delays in the harvest.

Rebecca reported hearing sounds beneath her floor again last night.

Thomas insists it is merely the house settling in the dampness, but I have instructed Samuel to check the foundation tomorrow nonetheless.

There is no further mention of Samuel’s inspection, if it occurred at all.

The next entry, dated August 27th, returns to matters of household management and preparations for an upcoming visit from business associates of Thomas.

Rebecca is not mentioned again until September 10th when Elizabeth writes, “Rebecca has taken to her bed with complaints of headache and disturbed sleep.

Dr.

Mills prescribed lordum, though I wonder if her condition might not be improved simply by relocating to the west wing away from the morning sun.

Thomas will not hear of it, saying arrangements have been made and cannot be altered.

What arrangements Thomas Caldwell referred to remain unclear from the available documentation.

The layout of the Caldwell home, reconstructed from architectural drawings filed with the county in 1836 and later amended in 1840, shows that the east wing contained four rooms, a bedroom, a small sitting room, a private bath, and a storage room accessed through a narrow door in the bedroom’s eastern wall.

This storage room shared its northern wall with a back staircase that led down to what the plans label as service areas.

September of 1842 brought a restbite from the rains, but an increase in temperature that was noted by several diarists of the period as unusual and oppressive.

Reverend William Stokes of the Third Presbyterian Church in Mobile wrote on September 15th that the Lord has seen fit to replace the floods with a heat that tests the endurance of his flock.

Many have taken ill, and attendance at services has diminished considerably.

Among those absent from church was the Caldwell family, who, according to Elizabeth’s diary, had remained at home for three consecutive Sundays due to Thomas’s concerns about contagion in town.

It was during this period of isolation that the relationship between the Caldwells and Rebecca Fontaine appears to have deteriorated significantly.

A letter from Elizabeth to her cousin in Virginia, dated September 23rd, hints at growing tensions.

Rebecca’s disposition has become increasingly difficult.

She keeps to her rooms most days, claiming weakness, yet Thomas reports hearing her moving about at all hours of the night.

The servants are reluctant to attend to her rooms, which I attributed to laziness, until Mary confessed that Rebecca had accused her of moving her possessions and standing over her bed while she slept.

I assured Mary that her mistress has been unwell and may have been confused by the effects of her medicine, but the girl seemed unconvinced.

The first direct reference to Isaac in connection with these events appears in an entry from the plantation’s work assignment ledger dated September 25th.

Isaac returned from North Fields to assist with repairs to East Wing Foundation.

Williams to oversee.

This entry is followed by another on September 28th that simply states Isaac reassigned to house duties by order of Mr.

C.

What transpired between September 28th and October 12th is largely undocumented.

The gap in Elizabeth’s diary during this period was later attributed to a brief trip she made to visit her ailing mother in Montgomery.

Though this explanation comes from a much later source, an interview conducted in 1912 with Martha Caldwell, Thomas and Elizabeth’s daughter, who was 7 years old in 1842.

In this interview preserved in the Mobile Historical Society’s oral history collection, an elderly Martha recalls, “Mother went to see her mother who was ill.

Father remained at the estate with Aunt Rebecca.

I was sent to stay with the Hendersons in town because there was sickness at our house.

” That’s what they told me.

Anyway, when I returned home, Aunt Rebecca was gone.

Indeed, the next entry in Elizabeth’s diary, dated October 13th, makes no mention of her absence, but does confirm Rebecca’s departure.

Returned to find the household in disarray, and Rebecca gone.

Thomas claims she left for Charleston on the 7th, though no note was left for me.

Her rooms have been emptied of her possessions.

Thomas has instructed that the east wing be closed until further notice due to concerns about the foundation.

Isaac is to nail shut the connecting door today.

This version of events that Rebecca Fontaine had suddenly departed for Charleston might have remained the accepted truth had it not been for the discovery made in 1959 during an expansion of Route 15, which required the excavation of a small portion of what had once been the northwestern edge of the Caldwell property.

The remains uncovered during this road work were initially assumed to be from an unmarked slave burial ground, not uncommon on large Antibbellum properties.

However, forensic examination revealed something more troubling.

Among the remains of what appeared to be five individuals were those of a Caucasian woman estimated to have been between 30 and 40 years of age at the time of death, wearing the fragments of what had once been a gold locket containing a miniature portrait that had deteriorated beyond recognition.

The discovery prompted a limited investigation by county authorities, but with the events in question having occurred more than a century earlier, there was little official interest in pursuing the matter beyond documentation.

The remains were eventually reinterred in Mobile’s old Magnolia Cemetery in an unmarked grave.

The incident filed away in county records with a note that the identification was inconclusive but presumed to be connected to the Caldwell estate based on location.

What connects Rebecca Fontaine to these remains is circumstantial but compelling.

A letter from Elizabeth Caldwell to Rebecca dated November 5th, 1842 was returned unopened marked recipient unknown at this address.

This letter preserved in the Caldwell family papers donated to the Mobile Historical Society in 1938 contains Elizabeth’s increasing concern about her sister’s silence and mentions that Thomas maintains you were determined to make a fresh start and did not wish to maintain connections that might remind you of your sorrows.

The fate of Isaac following these events is documented with chilling brevity.

Records from the port of Charleston show no arrival of a Rebecca Fontaine in October of 1842.

Nor does her name appear in any subsequent census or church records in South Carolina.

The plantation ledger for October 15th contains a single line Isaac sold to J.

Morrison Beloxy.

No bill of sale corresponding to this transaction has ever been found.

nor does the name Isaac appear in any records of sales to a J Morrison or any other buyer in Mississippi during this period.

What does exist, however, is an entry in the St.

Luke’s Parish death register dated October 16th, 1842.

Male property of T.

Caldwell, buried on estate grounds.

Cause accident during repair work.

Thomas Caldwell’s business correspondence from late October through December of 1842 shows a man apparently untroubled by recent events.

He negotiated the purchase of additional land to the west of his existing property entered into a new partnership for the export of cotton to Liverpool and made arrangements for his son Robert to attend school in Virginia the following year.

The only hint of disruption comes from a letter to his banker dated November 3rd in which he mentions, “The unfortunate incident at my property last month has been resolved to my satisfaction, though it necessitated unexpected expenditures which I expect to recoup through the enclosed venture.

” Elizabeth’s diary entries from this period reveal a different perspective.

On October 25th, she writes, “I have written to Charleston again, but have little hope of a reply.

Thomas forbids further discussion of the matter and becomes angry when I press him on the contradictions in his account.

The East Wing remains sealed, though I notice Thomas has taken to inspecting the work each evening before retiring.

” On November 18th, she notes, “Woke again to the sound of movement in the sealed section of the house.

When I mentioned it at breakfast, Thomas suggested I take additional lordinum at night.

I refused, saying I preferred to keep my wits about me.

He looked at me strangely, then a look I have not seen before and do not wish to see again.

By December, Elizabeth’s entries become increasingly concerned with her own safety.

On December 7th, have moved Caroline into my dressing room at night, claiming I need her assistance early in the mornings.

The truth which I dare not speak aloud is that I no longer feel safe sleeping alone.

Thomas’s behavior grows more erratic.

Yesterday he spent 3 hours in the east wing having broken his own seal on the door and emerged covered in dust claiming to be inspecting for termites.

Her final entry for 1842 dated December 31st is perhaps the most disturbing.

The year ends with frost on the windows and ice in my heart.

I am convinced now that Rebecca never left for Charleston, that whatever accident befell Isaac was no accident at all, and that my husband’s soul has been consumed by something I cannot name.

I have written to father asking if Carolyn and the children might visit him in Montgomery.

I did not say that I have no intention of returning, if he consents.

Elizabeth’s plan, if indeed she had formed one, was never realized.

According to church records, she fell ill in early January of 1843 with what was diagnosed as pneumonia and died on January 12th.

Thomas Caldwell remarried 6 months later to Margaret Wilson, the 22-year-old daughter of a business associate.

The east wing of the house remained sealed, according to Martha Caldwell’s later recollection, until a fire in 1849 damaged much of the main structure, necessitating extensive rebuilding.

The property remained in the Caldwell family until 1878 when it was sold following Thomas Caldwell’s death.

The new owners, the Mercer family, reported no unusual occurrences during their 20-year occupation of the rebuilt house.

However, a series of owners followed, none staying longer than 5 years.

By 1920, the main house had been abandoned, though the surrounding land continued to be farmed by tenants who lived in smaller structures on the property.

In 1958, historian Dr.

Elellanena Tate of Mobile University began researching the history of the Caldwell estate as part of a broader study of antibbellum plantation life in southern Alabama.

It was Dr.

Tate, who first connected the fragmentaryary evidence surrounding the disappearances of Rebecca Fontaine and Isaac, though her academic paper on the subject published in the Journal of Southern History in 1959 was careful to present multiple possible interpretations of the available evidence.

While it is tempting to construct a narrative of foul play from these scattered documents, she wrote, “We must acknowledge that other explanations exist.

Rebecca Fontaine may indeed have left Alabama, perhaps under a different name or to a destination other than Charleston.

The enslaved man Isaac may have been sold, despite the lack of confirming documentation, as recordkeeping for such transactions was not always meticulous.

The remains discovered during road work, while raising troubling questions, cannot be definitively identified as those of any specific individual.

Doctor Tate’s caution was academically sound, but perhaps diplomatically motivated as well.

Her research had been met with resistance from several prominent mobile families with connections to the Caldwells, who objected to what they characterized as sensationalist speculation about respected ancestors.

Following the publication of her paper, Dr.

Tate shifted her focus to less controversial aspects of regional history and did not publish further on the Caldwell case.

The story might have ended there, consigned to academic footnotes and local rumor, had it not been for the discovery made in 1968 during the demolition of the last standing structure on what had once been the Caldwell property.

Workers clearing the foundation of what had been a storage building uncovered a metal box that had been sealed within a wall.

Inside were several items.

A leather-bound book whose pages had largely deteriorated from moisture damage, a gold locket containing a miniature portrait of a woman remarkably well preserved, and a folded document that appeared to be a partially burned letter.

The items were turned over to the Mobile County Historical Commission where they remained largely forgotten until 1962 when archavist James Peon undertook the painstaking work of trying to preserve and decipher the damaged book.

What he found were fragments of what appeared to be a personal journal belonging to Rebecca Fontaine.

The entries, those that could be read, painted a disturbing picture of her final months.

Unleible passage dated approximately September 1842 reads, “Tea grows bolder in his visits.

Last night he did not even wait until the household was asleep.

” When I threatened to tell E, he laughed and said no one would believe the ravings of a grieving widow known to take Lordinham.

I fear he is right.

another fragment from what appears to be late September.

I have spoken with I.

He has agreed to help me leave this place.

He knows of a ship leaving for New Orleans next week, and will arrange passage.

I have promised him funds to purchase his own freedom once we are safely away.

We must be careful.

T suspect something.

The final legible entry, undated but presumably from early October, contains just one chilling line.

He knows.

God help us both.

The burned letter, when carefully examined, proved to be addressed to Elizabeth Caldwell from someone identified only as M.

The date and much of the content were lost to fire damage, but one paragraph remained intact.

I feel I must inform you of rumors that have reached even Charleston regarding your husband’s conduct.

It is said that his interest in your sister has exceeded the bounds of family affection and that this has been noticed by several who were guests at your home last spring.

I would have kept silent, but your letter expressing concern about Rebecca’s failure to arrive here compels me to share what I have heard.

If she is not with you in Mobile and not here in Charleston, I fear there may be cause for grave concern.

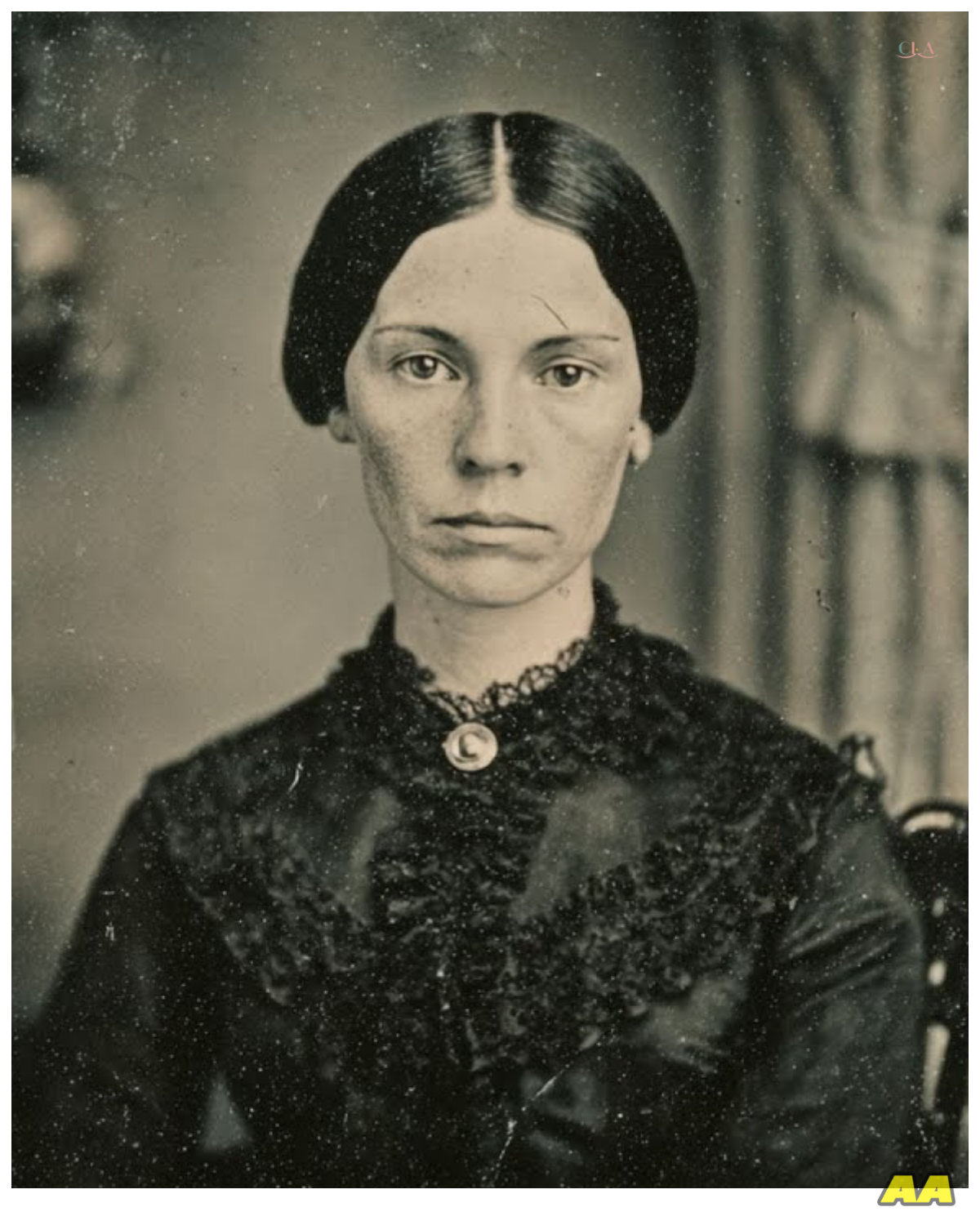

The portrait in the locket, when examined by art historians, was identified as being in the style of miniatures, popular in the 1830s and early 1840s, the subject was a woman approximately 30 years of age with dark hair and features that, according to Dr.

Peton’s notes bear a striking resemblance to Elizabeth Caldwell based on the family portrait currently housed in the Mobile Historical Society, suggesting this may indeed be her sister, Rebecca Fontaine.

These discoveries, while compelling, stopped short of providing definitive proof of exactly what had occurred at the Caldwell estate in 1842.

What they do suggest, however, is a narrative far more troubling than a simple departure or accident, one of unwanted advances, planned escape, discovery, and deadly consequence.

Thomas Caldwell’s subsequent success in business and standing in the community ensured that whatever actions he may have taken remained unexposed during his lifetime.

His second wife, Margaret, outlived him by nearly 20 years and was known for her charitable works and prominent role in mobile society.

Their descendants included judges, politicians, and business leaders who helped shape Alabama through the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

If they knew the dark history that had helped secure their prominence, they kept that knowledge to themselves.

The land where the Caldwell estate once stood is now divided between a shopping center, a residential development built in the 1980s, and a small wooded area that has been designated as protected wetlands.

Nothing remains of the original structures, the Oakline Drive, or any visible sign of the events that transpired there.

Route 15 cuts through what was once the northwestern corner of the property.

daily traffic passing over ground that held secrets for over a century.

In a final strange coder to this story, construction workers building the Oak Hollow subdivision in 1987 reported finding what appeared to be the remains of a foundation that did not match any known structure on the property maps they were working from.

According to the construction foreman’s report, the foundation included what seemed to be a small room or chamber below ground level, approximately 8 ft square, with no visible means of entry or exit other than from above.

County records indicate that an archaeologist from Mobile University briefly examined the site, but found no items of historical significance.

The foundation was removed, the area filled in, and construction proceeded according to plan.

Today, the residents of Oak Hollow drive their cars, walk their dogs, and raise their families with no awareness of what may have occurred beneath their manicured lawns.

The story of Rebecca Fontaine and Isaac exists now only in scattered documents, academic papers read by few, and the occasional whispered story told by those who study the darker corners of Mobile’s history.

Some stories, it seems, are buried so deeply that even time cannot fully unearth them.

What remains are only fragments like pieces of a shattered mirror that reflect different angles of a truth we can never fully reconstruct.

Perhaps that is as it should be.

Some mysteries once fully illuminated might prove too terrible to contemplate.

In 1968, shortly before his retirement, Dr.

James Peetton wrote in his final notes on the Caldwell case, “History is not merely what can be proven beyond doubt, but what echoes through time, however faintly, waiting for someone to listen.

The voices of Rebecca Fontaine and Isaac have echoed for more than a century.

Whether anyone is willing to hear them remains to be seen.

That question lingered still until the summer of 1969 when Katherine Morris, a graduate student in archaeology at Mobile University, chose the Caldwell estate as the subject of her thesis work.

Unlike her predecessors who had approached the site from a purely historical perspective, Catherine was interested in what physical evidence might remain beneath the soil, what secrets the earth itself might still hold about the events of 1842.

Permission for a limited excavation was initially denied by the county commissioners, who cited concerns about disrupting the wetlands that now occupied a portion of the former estate.

It was only through the intervention of Dr.

William Hargrove, a respected historian whose family had deep connections in mobile society, that Catherine eventually received conditional approval to conduct a 3-week examination of a small area near where Route 15 cut through the property.

Catherine’s field notes, preserved in the Mobile University archives, document her methodical approach.

Day one have established a grid system covering approximately 800 square f feet of the former northwestern corner of the Caldwell property.

Surface examination reveals nothing of note.

We’ll begin shallow test pits tomorrow.

For the first week, her entries remain similarly mundane, cataloging soil compositions, modern debris, and occasional fragments of 19th century ceramics and glass.

typical artifacts for a long occupied property, but nothing that added new dimensions to the Caldwell mystery.

On the eighth day of excavation, however, Catherine’s notes take on a different tone.

Test pit 7, approximately 60 cm below surface level, has yielded an unusual concentration of ash and charred wood.

The pattern suggests controlled burning rather than a natural fire spread, expanding the pit to determine extent.

The following day’s entry continues.

The burn layer extends approximately 10 ft in diameter.

Initial examination suggests animal remains, possibly domestic livestock, though formal identification will require laboratory analysis.

Catherine’s excavation continued for another week, during which she uncovered what she described as a deliberately constructed pit approximately 6 ft in diameter and 4 ft deep, its bottom lined with a layer of quick lime beneath the ash and bone fragments.

Her final field notes include a troubling observation.

Among the materials recovered from the pit are three metal buttons consistent with those used on women’s garments of the 1840s period and a partial human mer that shows evidence of dental work unusual for the period but consistent with methods used for wealthy patients.

Laboratory analysis later confirmed that the pit contained the remains of at least two individuals, though the condition of the bones subjected to both fire and chemical deterioration from the quick lime made more specific.

Identification impossible.

Katherine’s thesis, submitted in 1970, carefully outlined the evidence, but stopped short of definitive conclusions, stating only that the discovery of a limelined pit containing human remains on what was once the Caldwell property raises significant questions about previously documented disappearances associated with the estate.

The university archaeology department, perhaps wary of controversy, declined to pursue further excavation at the site, and Catherine’s findings, were published only in an academic journal with limited circulation, have found fragments of what appears to be bone intermixed with the ash.

She went on to a career in Mesoamerican archaeology, never returning to the Caldwell case.

When contacted by a local historian in 1982 about her earlier work, she responded with a brief letter stating only, “My research speaks for itself.

I have nothing further to add to the record.

” The physical changes to the former Caldwell property continued throughout the 1970s and 80s.

The construction of Oak Hollow subdivision covered most of what had been the eastern portion of the estate, including the area where the main house had stood.

The wetlands to the south were designated as a nature preserve, while the northwestern section became part of a commercial development that included a strip mall and office complex.

It was during the excavation for the office complex’s parking garage in 1984 that workers made another discovery.

According to the incident report filed with the county planning office, excavation equipment uncovered what appeared to be a brickline tunnel approximately 4 ft high and 3 ft wide running roughly east to west.

The tunnel extended only 12 ft before ending in a collapse, making it impossible to determine its original length or purpose.

County archaeologist Martin Simmons conducted a brief examination before construction resumed.

His report noted that the construction methods and materials are consistent with mid9th century techniques and that similar tunnels have been documented on other antibbellum properties typically used for food storage or as part of drainage systems.

This explanation was accepted without question.

The tunnel was filled in and construction continued according to schedule.

What Simmons’s report failed to mention, though it was noted in his personal journal, later donated to the Mobile Historical Society by his widow, was the discovery of a small object found embedded in the tunnel’s wall.

Recovered from the mortar between bricks approximately 8 ft into the tunnel was a tarnished silver thimble with the initials RF engraved on its band, Simmons wrote.

Given the context of the Caldwell property and previously documented individuals associated with it, the possibility that this belonged to Rebecca Fontaine cannot be dismissed.

Why Simmons chose to emit this detail from his official reports unknown.

In a later entry in his journal dated two weeks after the tunnel’s discovery, he noted, “Received a call today from James Caldwell Harper regarding the tunnel found on the former Caldwell property.

” Though he identified himself as a concerned citizen with an interest in historical preservation, his questions seemed more focused on what might have been found within the tunnel.

When I mentioned the possibility of a future more thorough examination, he became quite insistent that such work would be disruptive to development and serve no practical purpose.

As a descendant of the Caldwell family through his mother’s line, his interest is perhaps understandable.

James Caldwell Harper was at that time a prominent attorney in Mobile and a member of the city council.

No further investigation of the tunnel took place, and Simmons’s journal entries on the matter end with a cryptic comment.

Some doors, once opened, cannot easily be closed again.

Perhaps it is better to let sleeping histories lie undisturbed.

The thimble itself disappeared from the county’s archaeological collection sometime in the late 1980s.

A catalog entry indicates it was on loan for exhibition, but no record exists of which exhibition or whether it was ever returned.

When the collection was digitally cataloged in 1994, the thimble was listed as location unknown.

For nearly a decade, the Caldwell story again receded from public awareness.

Then in 1996, local historian Elellanena Wright began researching a book on prominent mobile families of the Antibbellum period.

Her request to access the Caldwell family papers, which had been donated to the Mobile Historical Society decades earlier, but were rarely consulted, led to an unexpected discovery.

While examining correspondence from the 1842 to 1843 period, Wright later wrote in the preface to her book, I found that several pages appeared to have been carefully cut from the bound volume of Thomas Caldwell’s business letters.

More curious still was the discovery of a previously uncataloged envelope tucked into the binding containing a fragmentaryary letter dated October 18th, 1842, addressed to Thomas Caldwell from someone identified only as JM of Beloxy.

The letter’s contents were brief but suggestive.

Matter resolved as discussed.

Payment received.

No further correspondence on this subject will be necessary or welcome.

Wright noted that the initials JM corresponded to the J.

Morrison mentioned in the plantation ledger as having purchased Isaac just days earlier, raising questions about what matter had been resolved and what service had actually been rendered in exchange for the payment received.

Wright’s research also uncovered a previously overlooked entry in the records of First Presbyterian Church in Mobile dated October 21st, 1842.

The entry in the pastor’s visitation log noted called upon T.

Caldwell at his request.

He sought prayer and counsel regarding what he termed a necessary but troubling action taken to protect family honor.

reminded him of scriptures teachings on mercy and justice.

Left with concerns about his spiritual state in her book mobiles founding families power and legacy in antibbellum Alabama published in 1997 Wright included a chapter on the Caldwells that carefully outlined the known facts about Rebecca Fontaine’s disappearance and the circumstantial evidence connecting it to the fate of Isaac.

The book received limited attention outside academic circles, though one review in the mobile register noted that Wright’s clinical examination of the Caldwell family history raises uncomfortable questions about the foundations upon which some of our city’s most respected lineages are built.

Following the book’s publication, Wright reported receiving several anonymous phone calls warning her against digging into matters best left forgotten.

She dismissed these as pranks, but colleagues noted that she subsequently shifted her research focus to the reconstruction era, leaving the antibbellum period largely unexplored in her later work.

The most recent chapter in the Caldwell mystery began in 2002 when Hurricane Matthew caused significant damage across the mobile area, including flooding in parts of the Oak Hollow subdivision built on the former Caldwell land.

The flooding was particularly severe in the northeastern section of the development where four homes suffered foundation damage serious enough to require evacuation.

During repairs to the home at 17 Oak Hollow Lane, construction workers made a grim discovery.

As they excavated around the damaged foundation, they uncovered human remains approximately 6 ft below the current ground level.

Work was halted and the county coroner’s office was called to the scene.

Initial examination determined that the remains were historical rather than recent and archaeologists from Mobile University were brought in to conduct a proper excavation.

What they found, according to the official report filed with the county, were the remains of two individuals who had been buried without coffins in what appeared to be a hastily dug grave.

One set of remains was identified as belonging to a male of African descent approximately 20 to 30 years old.

The second was identified as a female of European descent 30 to 40 years of age.

Dr.

Samantha Torres, the forensic anthropologist who examined the remains, noted several significant findings in her report.

The male skeleton showed evidence of healed fractures to two ribs and the left radius, consistent with injuries that would have occurred at least a year before death.

More tellingly, both the male and female remains exhibited fractures to the cervical vertebrae consistent with traumatic injury to the neck in lay terms broken necks.

The pattern of injury observed in both individuals, Dr.

Torres wrote is consistent with death by hanging.

The female remains also show a fracture to the right temporal bone that may have occurred permortm or shortly before death, suggesting a blow to the head.

Based on the positioning of the remains and the lack of formal burial arrangements, these do not appear to be judicial executions, but rather clandestine disposals of bodies.

Radiocarbon dating placed the time of death in the early to mid9th century, consistent with the 1842 time frame of Rebecca Fontaine and Isaac’s disappearances.

Found with the remains were several artifacts.

A corroded metal button, fragments of what appeared to be a woman’s shoe, and most significantly, a small gold locket containing a miniature portrait damaged almost beyond recognition by time and moisture.

DNA testing was attempted, but yielded inconclusive results due to the degraded condition of the remains.

Without a direct descendant of Rebecca Fontaine for comparison, positive identification remained impossible from a scientific standpoint.

However, the circumstantial evidence, the location, the estimated time period, the manner of death, and particularly the locket similar to the one described in Rebecca’s possessions, pointed strongly to a specific conclusion.

The discovery prompted renewed interest in the Caldwell case, including a feature article in the Mobile Register titled The Ghosts of Oak Hollow: A Century Old Mystery Resurfaces.

The article detailed the historical disappearances, the various discoveries made over the decades, and the most recent findings.

It closed with a quote from Dr.

Torres.

As scientists, we can only state what the physical evidence tells us.

These individuals died violently and were buried secretly on what was then the Caldwell property.

History has recorded the mysterious disappearance of two people from that property in 1842.

Whether these remains belong to those individuals cannot be stated with absolute certainty, but the convergence of evidence is compelling.

Public reaction to the article was mixed.

Some readers expressed shock and called for a memorial to be established for the victims.

Others, including several descendants of old Mobile families, criticized the newspaper for sensationalizing unproven allegations and tarnishing the reputations of respected historical figures based on circumstantial evidence.

Perhaps most telling was a letter to the editor published 3 days after the article signed by Margaret Caldwell Harper, great great granddaughter of Thomas Caldwell.

While I cannot speak to the specific events of 1842, I can say that our family, like many others of that era, has a complex history that includes both achievements and failings.

If indeed my ancestor was responsible for the deaths of Rebecca Fontaine and Isaac, no amount of family loyalty can justify such actions.

Perhaps the time has come for all of Mobile to examine its past with clear eyes, whatever uncomfortable truths may emerge.

The remains discovered in 2002 were eventually reinterred in Old Magnolia Cemetery with a simple marker reading two unknown souls.

Seagure 1842.

May they find the justice in death that was denied them in life.

The ceremony, though small, was attended by representatives from several historical organizations, members of local churches, and notably three descendants of the Caldwell family, including Margaret Caldwell Harper.

In the years since, the story has gradually become part of Mobile’s historical narrative, included in some walking tours of the downtown area and mentioned in books about Alabama’s Antibbellum period.

The Oak Hollow subdivision continues to expand with new homes built each year on land that once belonged to Thomas Caldwell.

Most residents know little of the property’s history, though occasionally rumors surface about strange sounds heard in the oldest sections of the development, particularly on rainy nights in October.

The most recent development in the long fragmented story of Rebecca Fontaine and Isaac came in 2008 when renovations to the Mobile County Courthouse uncovered a sealed compartment behind a section of wood paneling in what had once been the judge’s chambers.

Inside was a leather portfolio containing several documents, including a handwritten confession dated January 2nd, 1867 and signed by James Morrison of Beloxy, Mississippi.

The confession now preserved in the Mobile Historical Society archives reads in part, “As I face my own mortality, I am compelled to unbburden my soul of a sin that has weighed upon me these 25 years.

” In October of 1842, I was approached by Thomas Caldwell of Mobile with an offer of substantial payment to assist in what he called a matter of family honor.

I traveled to his estate on the night of October 7th and helped him to hang two individuals, a woman he identified as his sister-in-law, who he claimed had been engaged in immoral behavior that threatened his family’s standing, and a male slave who he said had been conspirator to her sins.

I did not question his authority to dispense such justice, as was the custom of that time.

We buried the bodies on his property at the edge of the north fields.

He then created a false record indicating he had sold the slave to me, though no such transaction occurred.

I returned to Beloxy with blood money that has profited me nothing but misery in the years since.

May God have mercy on my soul, though I deserve none.

The document’s authenticity has been verified by multiple experts in historical manuscripts who confirm that the paper, ink, and handwriting are consistent with the period.

What remains unknown is how the confession came to be sealed within the courthouse walls or why it remained hidden for so long.

With the discovery of Morrison’s confession, the basic outline of what happened at the Caldwell estate in October of 1842 seems clear.

Thomas Caldwell, perhaps motivated by inappropriate interest in his sister-in-law that was rebuffed, or perhaps by discovery of a planned escape that threatened his authority and property, resorted to murder to eliminate both problems at once.

His wealth standing and the unquestioned authority granted to white male property owners in Antabbellum, Alabama allowed him to literally bury his crimes and continue his life unimpeded, building a legacy that would benefit his descendants for generations.

Yet questions remain.

The tunnel discovered in 1984 suggests an infrastructure of concealment more extensive than would be needed for a one-time crime of passion.

The multiple burial sites identified over the years indicate that the two bodies found in 2002 may not tell the complete story of what happened at the Caldwell estate.

And the persistent references in Elizabeth Caldwell’s diary to sounds and movements in the sealed east-wing hint at possibilities more disturbing than a simple, if brutal, double murder.

Some of these questions may eventually be answered as technology advances and new evidence emerges from archives or excavations.

Others may remain perpetually beyond our reach, lost to time and deliberate concealment.

What is certain is that beneath the manicured lawns of Oak Hollow, beneath the asphalt of Route 15, beneath the foundations of the strip mall and office complex, lies a history darker than most care to acknowledge.

A history of power abused, lives extinguished, and truth suppressed.

In 2009, a plaque was installed at the entrance to the Oak Hollow subdivision, largely due to the efforts of Margaret Caldwell Harper and the Mobile Historical Preservation Society.

The plaque acknowledges that the land once belonged to the Caldwell Plantation and includes the names of all known individuals, both free and enslaved, who lived and died there.

Among those names are Rebecca Fontaine and Isaac listed with the simple notation disappeared October 1842 remains discovered 2002.

It is a small acknowledgement centuries delayed of lives cut short and voices silenced.

Whether it represents justice, reconciliation, or merely a footnote to a largely forgotten history depends perhaps on one’s perspective.

What it does provide is a reminder that the past is never truly buried, that secrets hidden in darkness eventually find their way to light, and that the actions of one generation continue to resonate through those that follow.

For the modern residents of what was once the Caldwell estate, life continues in its ordinary rhythms.

Children play in backyards that may once have been sights of unspeakable cruelty.

Families gather for dinner in dining rooms built above ground that may hold forgotten graves.

Most give little thought to what might have happened on that same soil nearly two centuries ago.

But on certain nights, when the rain falls heavily and the wind moves through the remaining stands of old oak trees, some residents report a strange heaviness in the air, a sense of being watched, or the distant sound of what might be weeping.

Those familiar with the history might attribute such experiences to the power of suggestion, or an overactive imagination influenced by knowledge of past tragedies.

Others perhaps might wonder if some echoes never fully fade.

If some wounds never completely heal, if some injustices continue to demand acknowledgement long after those who committed them have turned to dust.

The story of Rebecca Fontaine and Isaac, pieced together from fragments of documents, archaeological discoveries, and generations of inquiry, remains ultimately incomplete.

Like most historical narratives, it exists in the space between what can be proven and what can be reasonably inferred, between documented fact and necessary supposition.

What seems clear beyond the specific details that may never be fully known is that it stands as a testament to the human capacity for both cruelty and concealment, and to the way in which privilege and power have historically enabled both.

In her final public statement on the matter before her death in 2012, Margaret Caldwell Harper perhaps said it best.

The story of Rebecca and Isaac is not just a Caldwell family story.

It’s an American story, one repeated in different forms on different properties across the South.

If we truly wish to understand our present and shape a better future, we cannot continue to avert our eyes from these difficult truths.

The ghosts of our past do not rest because we refuse to acknowledge them.

They rest when we finally have the courage to look them in the face and speak their names.

And so we have spoken their names.

Rebecca Fontaine and Isaac.

What happened to them on the Caldwell estate in October of 1842 may never be known with absolute certainty.

But in piecing together their story, in refusing to allow their disappearance to remain unexplained and unmourned, perhaps we offer a belated form of witness to lives that were deemed disposable by the moral calculations of their time.

The land that once belonged to Thomas Caldwell has been transformed beyond recognition.

The buildings he constructed have long since returned to dust.

His name is remembered primarily in the context of the crime he likely committed rather than the fortune he amassed or the position he held.

And in that transformation lies perhaps the most fitting epilogue to this long and fragmented story.

That power, no matter how absolute it may seem in its moment, eventually falters.

That secrets, no matter how deeply buried, eventually surface, and that truth, no matter how long delayed, eventually finds its voice.

In the archives of the Mobile Historical Society, the confession of James Morrison, the fragments of Rebecca Fontaine’s journal and the diary of Elizabeth Caldwell rest side by side in climate controlled storage, paper witnesses to events long past.

In Old Magnolia Cemetery, the remains of two individuals who may be Rebecca and Isaac lie beneath a simple marker, finally acknowledged, if not fully known.

And in Oak Hollow, life continues.

New stories unfold, while beneath the surface the old stories wait, not ended, not forgotten, but incorporated into the ongoing narrative of a place and its people.

Some wounds never heal completely.

Some stories never conclude definitively.

Some mysteries retain their core of darkness even when exposed to light.

The case of Rebecca Fontaine and Isaac Caldwell, if indeed the remains are theirs, stands as testament to this truth.

It reminds us that history is not a settled account, but an ongoing conversation between past and present, between what is known and what remains hidden, between justice delayed and justice denied.

Perhaps that is as it should be.

Complete resolution, after all, might allow us the comfort of closure, of filing away difficult truths as settled matters, no longer requiring our attention or concern.

The very incompleteness of this narrative keeps it alive, keeps it relevant, keeps it pressing upon our contemporary conscience questions about power, justice, and whose stories we choose to remember.

As you drive down Route 15, past what was once the northwestern corner of the Caldwell property, there is nothing to indicate that you are passing over ground that may have held terrible secrets for more than a century and a half.

The landscape offers no visible reminder of Rebecca Fontaine or Isaac, of Thomas Caldwell’s crimes or Elizabeth’s suspicions.

Life has moved on.

The world has transformed.

Yet something remains in documents preserved, in stories told, in names spoken after generations of silence.

Something that reminds us that the past is never truly past, that it continues to shape our present in ways both acknowledged and unrecognized.

Something that whispers like the wind through Spanish moss on an October night in Mobile.

Remember, witness, speak truth to power, even when that power has long since crumbled to dust.

For Rebecca Fontaine and Isaac, truth came too late for justice in this world.

For us, their story offers a chance to recognize that some debts can never be fully paid, some wrongs never fully writed.

But acknowledgment itself has value.

In speaking their names, in telling their story, fragmented and incomplete as it remains, we affirm that their lives mattered, that what happened to them matters still, and that in the long arc of human memory, even those who were silenced may eventually find voice.

News

✈️ U.S. F-15 FIRST STRIKE — ALLEGED CARTEL DRUG LAB ERASED IN SECONDS AS SKY ERUPTS IN A BLINDING FLASH ✈️ What officials described as a precision operation turned the night into daylight, with jets screaming overhead and a suspected production site reduced to smoking rubble in moments, sending a shockwave across the region and a message that the airspace above is no safe haven for hidden empires 👇

The Last Fortress: A Shocking Revelation In the heart of the Mexican jungle, Diego stood at the entrance of the…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: FBI & ICE SHATTER ALLEGED TRUCKING NETWORK WITH SOMALI TIES — 83 ARRESTED, $85M IN CASH AND WEAPONS STACKED AS EVIDENCE 🚨 Before sunrise, federal agents swept through depots and dispatch offices, hauling out duffel bags of currency and seizing firearms while stunned neighbors watched a logistics operation authorities claim was hiding a sprawling criminal enterprise behind everyday freight routes 👇

The Shadows of the Ghost Fleet In the heart of the Midwest, where the snow fell like a blanket over…

🚨 FBI & ICE STORM GEORGIA “CARTEL HIDEOUT” — GRENADE LAUNCHER DISCOVERED AND $900K IN DRUGS SEIZED IN A DAWN RAID THAT SHOCKED THE BLOCK 🚨 What neighbors thought was just another quiet morning exploded into flashing lights and tactical vests as agents swept the property, hauling out weapons and evidence while officials described a months-long investigation that culminated in a swift, coordinated takedown 👇

The Unraveling of Shadows: A Tale of Betrayal and Redemption In the heart of Jackson County, Georgia, the air was…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: DEA & FBI CRUSH ALLEGED CARTEL TRUCKING EMPIRE — HIDDEN ROUTES MAPPED, DRIVERS DETAINED, AND MILLIONS STACKED AS EVIDENCE 🚨 Before sunrise, highways turned into a grid of flashing lights as agents intercepted rigs, cracked open trailers, and traced coded dispatch logs, revealing what officials describe as a logistics web hiding in plain sight behind ordinary freight lanes 👇

The Fall of Shadows: A Cartel’s Empire Exposed In the dimly lit corridors of power, where shadows danced with deceit,…

🚢 U.S. NAVY TRAPS SINALOA CARTEL’S ALLEGED $473 MILLION “DRUG ARMADA” AT SEA — AND THE HIGH-STAKES STANDOFF UNFOLDS UNDER FLOODLIGHTS AND ROTOR WASH 🚢 Radar screens lit up, cutters boxed in fast boats, and boarding teams moved with clockwork precision as authorities described a sweeping maritime interdiction that turned open water into a chessboard, stacking seized cargo on deck while prosecutors hinted the ripples would travel far beyond the horizon 👇

The Abyss of Deceit: A Naval Reckoning In the heart of the Caribbean, where the turquoise waters glimmered under the…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: DEA & FBI DESCEND ON MASSIVE TEXAS LOGISTICS HUB — 52 TONS OF METH SEIZED AS 20 POLITICIANS ALLEGEDLY TIED TO A SHADOW NETWORK ARE THRUST INTO THE SPOTLIGHT 🚨 What began as a quiet federal probe detonated into a sweeping raid of warehouses and boardrooms, with agents hauling out towering stacks of evidence while stunned insiders whisper that the real shockwave isn’t just the drugs — it’s the powerful names now facing intense scrutiny 👇

Shadows of the Underground: The Texas Cartel Unveiled In the heart of Texas, where the sun sets over sprawling landscapes,…

End of content

No more pages to load