The Most Devastating Slave-Era Romance Mystery in Mobile History (1841)

Welcome to this recordo for one of the most unsettling cases registered in the history of mobile.

Before we begin, I invite you to leave in the comments where you are watching from and the exact time at which you are listening to this narration.

We are interested in knowing to which places and at what moments of the day or night these documented accounts reach.

Mobile 1841.

The port city stood as one of the busiest in America with cotton flowing from the surrounding plantations through its harbor.

Ships arrived daily carrying goods and sometimes human cargo despite the prohibition of international slave trading.

The streets were lined with grand homes owned by wealthy merchants and plantation owners.

Beautiful facads masking the darker realities of the time.

In one such home on Government Street, not far from the bustling commercial district, lived Abram Hollis, a 43-year-old free man of color.

He was unusual in mobile society, a skilled carpenter who had purchased his freedom 15 years earlier, and had since amassed modest wealth through his craftsmanship.

His hands were known for creating the finest cabinetry in mobile, furniture that adorned the homes of the city’s elite.

Hollis lived in a small but well-appointed home granted special dispensation to reside within the city limits due to his exceptional skills and connections to powerful white patrons.

Among these was Judge William Thompson, whose family had been among the first to settle Mobile after American acquisition.

The Thompson estate relied on Hollis for repairs and custom furniture, and the judge had personally signed papers allowing Hollis to remain in the city when other free people of color were being pressured to leave.

Two blocks from the St.

Francis Street Methodist Church, established just the year before was the property of the Maro family.

Jean Batist Morrow had arrived from New Orleans in the 1820s, establishing a shipping business that had flourished with the cotton boom.

Now in failing health, the business was primarily managed by his son Phipe, who had expanded it considerably.

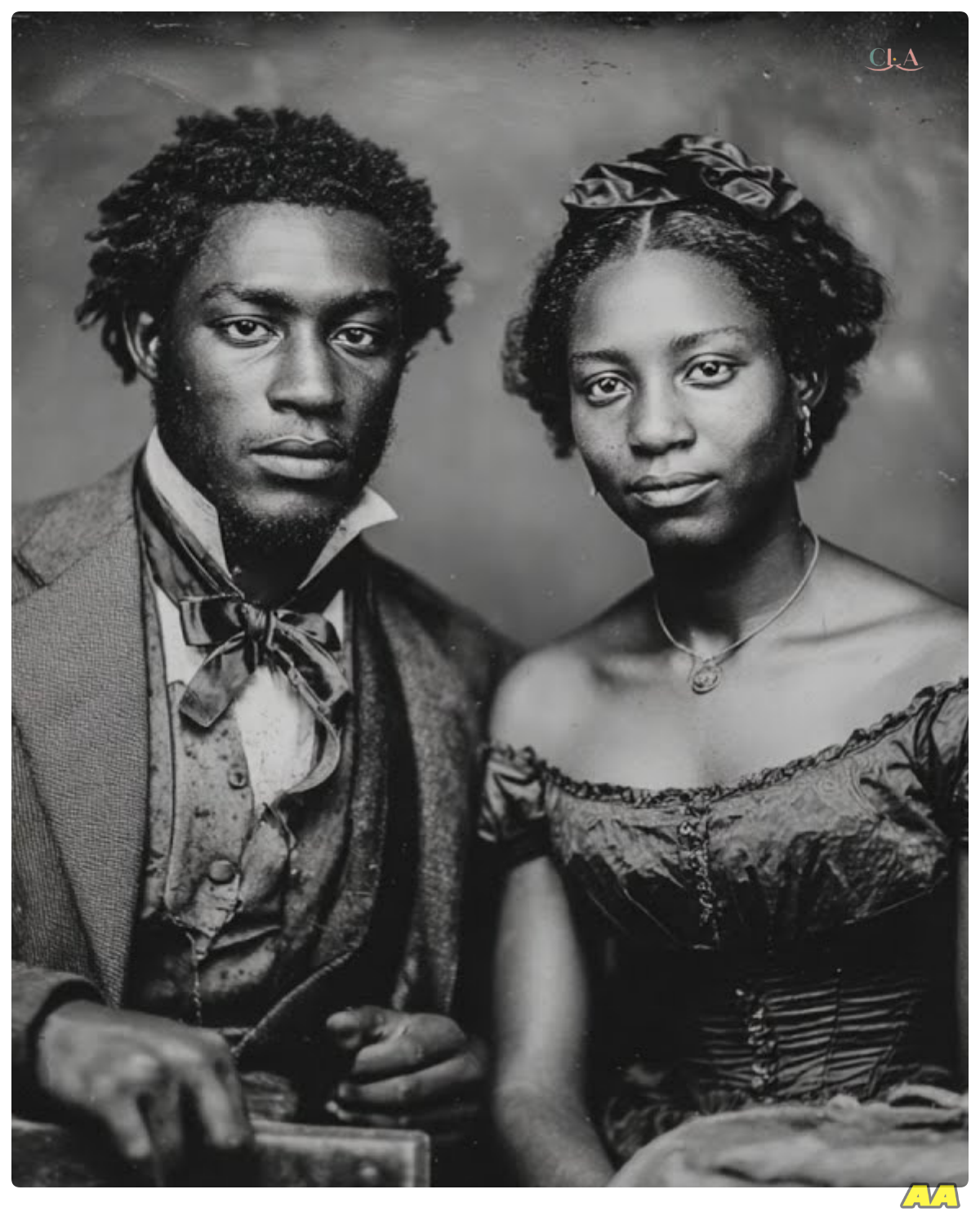

The Marose owned several enslaved people, including a young woman named Delilah.

At 22, Delila Maro was known for her intelligence and grace.

Born on a plantation in South Carolina, she had been purchased by the Marose as a young girl to serve as a ladies maid to Madame Maro.

Unlike many enslaved people, she could read and write, having been taught secretly by Madame Maro’s daughter before her marriage and relocation to Nachez.

Delilah was often seen accompanying Madame Maro to church or on errands through town, always impeccably dressed in the fine handme-downs her mistress provided.

Few would have guessed that Delila and Abram knew each other, let alone that they had formed a secret bond over the years.

Their connection had begun innocently enough at a Christmas service four years earlier, when Abram had been hired to repair pews at St.

Louis Cathedral, where the Marose worshiped.

a glance, a whispered word during communion, and something had sparked between them.

In the years that followed, they had developed a system for communication.

Abram would leave small carved wooden tokens in locations where Delilah might find them during her errands, a leaf here, a small bird there, signals that he wished to meet, and she would respond by placing a sprig of thyme near the back entrance of the church where he would find it.

But in 1841, their delicate relationship took a dangerous turn.

This is the story of what happened, pieced together from fragments of old letters, church records, court documents, and the whispers that echo still in the corners of mobile’s oldest buildings.

On the morning of February 20th, 1841, Abram Hollis was working in his small workshop behind his home.

The weather was unusually cold for Mobile, and a light rain tapped against the windows as he carved delicate filigree into a chest of drawers commissioned by the wife of a cotton broker.

His concentration was broken by a knock at the door.

It was Samuel Wilson, a white storekeeper with whom Abram had developed a cautious friendship over the years.

Wilson’s face was grim as he stepped inside, removing his wet hat.

They’re looking for you, Abram, Wilson said without preamble.

There’s talk about you and the Maro girl.

Dangerous talk.

Abram set down his tools carefully, his hands suddenly still.

Who’s talking? Philipe Marorrow himself.

He was at the coffee house this morning, drunk before 10:00, saying he had evidence that you had been meeting his father’s slave girl in secret.

Said he found letters.

This was impossible.

Abram knew.

Though Delilah could write, they had never dared exchange letters.

The risk was too great.

Something else must have happened.

“There’s more,” Wilson continued, lowering his voice though they were alone.

“He’s claiming that you’ve been plotting to help her escape, that you paid a captain to take her north.

” “That’s a hanging offense,” Abram.

The wood shavings at Abrams feet seemed to blur.

his life in mobile.

Everything he had built suddenly felt as fragile as the curls of Cyprus beneath his boots.

Where is she? Delilah, do you know where she is? Wilson shook his head.

Locked away, I’d imagine.

But Abram, you need to concern yourself with your own safety now.

Phipe has gone to Judge Harris.

They’ll come for you by nightfall.

That evening, as the city lamps were being lit, three men arrived at Abrams door.

One was the city marshal, the other’s deputies.

They had a warrant for his arrest on charges of conspiracy to steal slave property.

Abram was taken to the small city jail near the courthouse.

The cell was damp and cold with only straw on the stone floor.

Through the small barred window, he could see the spire of Christ Church in the distance silhouetted against the darkening sky.

For 3 days, Abram remained in that cell, permitted no visitors except for Judge Thompson, who came on the second day.

The judge looked troubled, his usual confident demeanor subdued.

The evidence against you is circumstantial, but compelling.

Thompson told him, “Philipe Maro claims to have found a map among Delilah’s possessions along with $30 in gold coins.

He says she confessed that you gave these to her along with instructions to meet a ship captain at the north dock next week.

It’s not true, Abram said quietly.

Thompson studied him for a long moment.

I believe you.

But I’m not sure it matters what I believe.

Philipe Maro has influence and he’s demanding the fullest punishment.

His father is dying and he seems determined to make an example of someone.

and Delilah.

What will happen to her? The judge looked away.

She’s to be sold at auction.

Phipe claims she can no longer be trusted in the household.

That night, unable to sleep on the hard stone floor.

Abram heard footsteps approaching his cell.

A lantern illuminated the face of a young deputy he didn’t recognize.

The man glanced nervously down the corridor before unlocking the cell door.

Judge Thompson sent me,” he whispered.

“There’s a horse waiting behind the Chandler.

Ride west until you reach the Clark plantation, then ask for Marcus.

He’ll help you cross into Mississippi.

” Abram hesitated.

“And Delilah?” The deputy shook his head.

“She’s being held separately.

There’s nothing we can do for her tonight.

” “Then I’m not leaving,” Abram said firmly.

The deputy looked startled.

You don’t understand.

They’re talking about a trial tomorrow with a judge who owes Philipe Maro money.

It will be a hanging by sunset.

I understand perfectly, Abram replied.

But I won’t leave without her.

The door closed, the key turned, and Abram was alone again with the darkness.

At dawn, he was awakened by the sounds of commotion in the street.

Looking through his small window, he could see a crowd gathering outside the jail.

For a moment, he feared it might be a lynch mob, but as he listened to their angry voices, he realized they were protesting something else entirely.

Hours later, Judge Thompson returned, this time with the marshall.

“There’s been an unexpected development,” Thompson said as the marshall unlocked the cell.

“Philipe Maro is dead.

” Abram stared at him in disbelief.

Dead.

How? Poison.

It appears he collapsed at breakfast this morning.

His slave, Delilah, was serving him, and witnesses say he accused her of something just before he fell.

She’s been taken to the courthouse square.

There’s a crowd gathering.

Outside, the streets were filled with people moving toward the courthouse.

Abram found himself being led through the crowd.

Thompson’s hand firmly on his shoulder.

The judge spoke quietly as they walked.

“Listen carefully, Abram.

I don’t know what happened between you and the Maro girl, and I don’t want to know.

But she’s been accused of murder now, and there’s nothing I can do to stop what’s coming.

Your charge of conspiracy has been dropped in light of this more serious crime.

But you need to leave Mobile today.

I’ve arranged passage for you on a ship to New Orleans.

From there, you must make your own way.

As they approached the courthouse square, Abram saw her.

Delilah stood on a wooden platform, her hands bound, surrounded by armed men.

Her face was bruised, but her posture remained proud.

The crowd around her was growing more hostile by the minute.

“She didn’t do it,” Abram said, his voice catching.

Phipe must have discovered something.

Something else.

Thompson’s grip on his shoulder tightened.

It doesn’t matter now.

You can’t help her.

Save yourself.

But Abram couldn’t look away from Delilah.

Even from a distance, he could see that her eyes were searching the crowd, perhaps looking for him.

There was no fear in her expression, only a terrible resignation.

Later that day, as a ship called the Augusta sailed from Mobile Bay toward New Orleans, Abram Hollis stood at the rail, watching the city recede into the distance.

In his pocket was a small wooden bird, the last token he had carved for Delilah, but never had the chance to leave for her.

He would never return to Mobile.

Records show that he eventually made his way to Philadelphia where he established himself once again as a carpenter, though he never achieved the status he had held in Mobile.

He never married.

When he died in 1867, the only personal effect noted in his sparse will was a small wooden bird to be buried with him.

As for Delila Maro, the Mobile Register reported her execution on March 3rd, 1841.

She maintained her innocence until the end.

The article noted that she showed uncommon dignity for one of her station in her final moments.

But that is not where this story truly ends.

In 1860, a yellowed letter was discovered during renovations to the old Maro House on St.

Emanuel Street.

It had been hidden in a secret compartment of a writing desk, a desk crafted by Abram Hollis years earlier.

The letter written in an elegant hand was addressed to Madame Maro from her daughter in Nachez.

It spoke of family matters mostly, but contained one passage that drew particular attention.

I worry for father’s health and pray daily for his recovery.

I must confess I fear Filipe’s ambitions more than father’s illness.

The way he speaks of the business as though it were already his chills me.

Last month he asked disturbing questions about the effects of certain herbs and minerals on health.

I told him nothing of course but I worry what knowledge he seeks and from whom.

The letter was dated January 12th 1841 6 weeks before Philip’s death.

It was filed away in the city records and largely forgotten as the Civil War soon engulfed the South.

In 1868, an elderly woman named Gabrielle Martin, who had been the housekeeper for the Maro family, gave a deathbed confession to a priest at the cathedral.

Though the details of confessions remain private, the priest was so troubled by what he heard that he wrote a letter to the bishop which survives in church archives.

In it, he asked for guidance regarding a grave injustice perpetrated 27 years ago against an innocent woman executed for a crime she did not commit, while the true murderer lived on, protected by his position and wealth.

The letter did not name names, but referred to one who poisoned his own father to accelerate his inheritance and then blamed an innocent servant when she discovered evidence of his earlier crime.

In the years that followed, the story of Abram Hollis and Delilah Maro faded from public memory.

The city grew and changed.

The old Maro house was demolished in 1892 to make way for a commercial building.

Judge Thompson’s court records were lost in a fire in 196.

But in 1952, during the renovation of the old saint Louie Cathedral, workers discovered something unusual beneath the floorboards of what had once been the sacry, a small tin box containing a folded piece of paper and a sprig of dried thyme, preserved remarkably well over the century since it had been hidden there.

The paper contained just a few lines written in a careful hand.

They say he poisoned his father slowly over weeks.

I found the bottles hidden in his room while cleaning.

Recognized them from my grandmother’s teachings.

He saw me looking.

Tomorrow I am to serve breakfast.

If you find this, know that I loved you and that whatever happens is not your doing.

D.

The box and its contents were given to the Diosisen Archives, cataloged, and eventually transferred to the Mobile Historical Society, where they remain to this day, a small but tangible link to a tragedy from Mobile’s past.

Some say that on quiet evenings in the oldest part of Mobile’s downtown, where the buildings still remember the 1840s, the scent of time sometimes drifts on the air, though no such herb grows nearby.

Others claim to have seen a woman in period dress, walking slowly along Government Street in the pre-dawn hours, as if searching for someone or something lost long ago.

These are just stories, of course, born from imagination and the human tendency to create narrative from tragedy.

But the documented facts remain.

Two people separated by the cruel realities of their time whose lives were destroyed by greed, suspicion, and injustice.

In 1965, the last living descendant of the Maro family, a great granddaughter of Phipe named Katherine Maro Wells, donated the family papers to the Mobile Historical Society.

Among them was a journal kept by Jean Batiste Morrow during the last year of his life.

Most entries focused on business matters or his deteriorating health, but one entry dated February 10th, 1841 stood out.

Phipe grows more impatient with each passing day.

I see how he looks at me when he thinks I’m not watching, calculating, measuring the time I have left.

Last night I heard him arguing with Delilah after she brought my evening medicine.

The girl seemed upset.

I must speak with her tomorrow.

There was no entry for February 11th.

The next entry dated February 15th was written in a shakier hand.

My strength fails me faster now.

The new medicine Philipe insists I take has a strange taste.

Delilah tried to speak with me privately today, but Philipe interrupted.

There is something in her eyes.

Fear or warning? I am too weak to puzzle it out.

The final entry dated February 19th consisted of just one line.

God forgive him for I understand now what he is doing.

The next day according to other records Jean Baptiste Maro died in his sleep.

Phipe inherited everything and the day after that he accused Abram Hollis of conspiring with Delilah to escape.

Some historians have suggested that Philipe discovered the relationship between Abram and Delilah and used it as an opportunity to silence Delilah who may have witnessed or suspected his patraside.

Others believe that Delilah in her desperation may have actually contemplated escape with Abrams help, giving Phipe the leverage he needed.

We may never know the complete truth.

The voices of Abram Hollis and Delilah Maro have been largely silenced by history.

Their story pieced together from fragments left behind by others.

But in those fragments, we can glimpse the human tragedy at the heart of this case.

Two people caught in circumstances beyond their control whose brief connection led them both to destruction.

In 1967, exactly 100 years after Abram Hollis died in Philadelphia, a descendant of Judge Thompson donated a collection of the judge’s personal papers to the University of Alabama archives.

Among them was a sealed envelope labeled simply a Hollis personal correspondence not to be opened until 100 years after my death.

Inside was a single letter written by Abram Hollis to Judge Thompson shortly before the judge’s death in 1871.

It read in part, “I have lived now for 30 years with the weight of that day.

Not a night passes that I do not see her face as I last saw it, proud and resigned.

I should have done more.

I should have spoken out.

Perhaps if I had confessed to planning her escape, even falsely, it might have lent credibility to her claims about Filipe.

But fear silenced me.

And for that, I cannot forgive myself.

You showed me kindness in helping me escape Mobile, and for that I thank you.

But I wonder if you knew even then what really happened.

Did you suspect Phipe of murdering his father? Did others? How many remained silent to protect the social order, to avoid the scandal of a prominent white businessman being accused by an enslaved woman? I have built a life here in Philadelphia, but it is a hollow one.

The small wooden birds I once carved for her as signals now fill my home.

Hundreds of them, each a memory, each a regret.

When I die, I wish only one to accompany me to the grave.

The rest I leave to the wind and the world.

The Thompson papers also contained a brief reply from the judge, never sent, found among his drafts.

Yes, I suspected.

Others did, too.

But suspicion is not proof.

And in our world, her word could never outweigh his.

I am sorry, Abram.

More sorry than you can know.

In 1938, during the excavation for a new building on the site of the old city jail, workers discovered a small wooden bird remarkably preserved in the clay soil.

No one could explain its presence or significance, and it was eventually discarded.

Had anyone recognized it as matching the description of Abram’s carvings, perhaps it might have been preserved, one more fragment of their story.

The most unsettling discovery, however, came in 1959.

During renovation work on an old warehouse near the docks, which had once been the customs house, a sealed brick chamber was found beneath the floorboards.

Inside was a human skeleton determined to be that of a man who had died in his 30s or 40s.

Beside the bones were several items, a pocket watch stopped at 10:17, a folded document that crumbled to dust when touched, and most disturbingly, a small vial containing traces of arsenic.

Forensic examination suggested the man had been walled up alive, perhaps dying slowly of suffocation.

No identification was ever made, and the remains were eventually reeried in the city cemetery.

But the discovery sparked renewed interest in old cases of missing persons from Mobile’s past.

Among these was the curious case of Philipe Morrow, who history recorded as having died of poisoning on February 22nd, 1841.

But parish records from New Orleans tell a different story.

They indicate that a man calling himself Philip Moro arrived in the city on February 25th of that year making a substantial donation to the church before departing for France.

No record of his arrival in France exists.

If Philipe Maro did not die on that February morning, then who did? And what became of Delilah executed for his murder? Some local historians have suggested that the body found in the customs house might have been the real Phipe Maro, perhaps killed by business rivals or creditors who then assumed his identity.

Others propose more elaborate theories involving switched identities and elaborate frames.

But the simpler and more horrifying possibility is this, that Philipe Mororrow faked his own poisoning, framed Delila for a murder that never occurred, and fled with his father’s fortune while an innocent woman was executed.

We may never know the complete truth.

Too much time has passed.

Too many records have been lost.

What remains are questions, suspicions, and the lingering sense of injustice that sometimes settles like evening fog over Mobile’s oldest streets.

In the summer of 1968, a history professor from the University of Alabama visited the site where the Maro house once stood.

He was researching a book on Antabbellum Mobile and had become fascinated by the Hollis Maro case.

As he stood contemplating the modern building that now occupied the space, an elderly black woman approached him.

“You’re looking for them, aren’t you?” she asked.

Abram and Delilah.

Startled, the professor acknowledged that he was researching their story.

The woman nodded.

“My great grandmother knew Delilah, worked in the same house for a time.

She said Delilah could see things before they happened, had the sight like her grandmother before her.

She knew what Philipe was doing to his father, and she knew what would happen to her for knowing.

“Why didn’t she run?” the professor asked.

The old woman smiled sadly.

“Because she loved Abram, and running would have put him in danger.

She chose to stay and try to stop Phipe instead.

” My great grandmother said Delilah told her the night before it all happened.

Some prices are worth paying if they protect those we love.

With that, the woman walked away, refusing to give her name or speak further with the professor.

He never located her again, despite extensive searching.

Her story may be apocryphal, one more layer of legend added to the historical record.

Or perhaps it contains a kernel of truth that documentary evidence cannot capture.

The human motivations and emotions that drove the events of those fateful days in February 1841.

In the end, what we know with certainty is limited.

Two people, Abram Hollis, a free man of color, and Delila Maro, an enslaved woman, formed a connection that crossed the rigid boundaries of their society.

Their story intersected with that of the Maro family in ways that led to tragedy.

And the echoes of that tragedy continue to resonate in Mobile’s collective memory, a reminder of the human cost of the systems and prejudices that once defined the city.

Some stories resist closure.

Some injustices can never be fully writed.

But in remembering Abram and Delilah, in piecing together the fragments of their lives, perhaps we offer them a small measure of the dignity and recognition that their world denied them.

As you walk the streets of Mobile today, pause sometimes to listen.

In the spaces between the noise of modern life, you might hear the echoes of the past, the tap of a carpenters’s hammer, the rustle of a lady’s maid preparing her mistress’s clothes, the scratch of a pen as a dying man records his final suspicions, the soft thud of a wooden bird being placed where someone might find it.

These are the sounds of lives once lived, of choices made and unmade, of love found and lost.

They are the heartbeat of history, still pulsing beneath the surface of the present.

And somewhere perhaps the scent of time still drifts on the evening air, carrying with it the memory of Abram Hollis and Delila Maro, separated by the circumstances of their birth, but united in tragedy, their story not forgotten, but whispered still in the shadows of Mobile.

In the years that followed the execution of Delila Maro, mobile changed dramatically.

The cotton trade continued to flourish, bringing ever more wealth to the city’s elite.

The grand homes along Government Street grew grander still, their gardens more elaborate, their furnishings more luxurious.

But beneath this veneer of prosperity and refinement, uncomfortable questions lingered about the events of 1841.

Jean Baptiste Maro’s shipping business, now managed by distant relatives who had arrived from New Orleans, gradually lost prominence.

The name Maro, once respected in Mobile’s business circles, became associated with whispers and sidelong glances.

People spoke of a curse, though few would admit to such superstition openly.

The Maro home on St.

Emanuel Street stood empty for years.

Attempts to sell it failed repeatedly as prospective buyers reported strange occurrences, unexplained cold spots, the persistent smell of herbs where none grew, the sound of footsteps in empty rooms.

Eventually, the property was purchased by the city and repurposed as administrative offices, though employees often requested transfers, citing an oppressive atmosphere that made work difficult.

In 1853, 12 years after the events that claimed Delilah’s life, a curious incident occurred at the mobile docks, a sailor newly arrived from Marseilles claimed to have encountered Philip Maro in a cafe in the French port city.

According to the sailor’s account recorded in the diary of a local merchant, the man he identified as Maro was well-dressed but haggarded with the haunted look of one pursued by demons.

When the sailor mentioned he was bound for mobile, the man reportedly became agitated, paid his bill hurriedly, and disappeared into the street.

The sailor’s story might have been dismissed as mere gossip had it not been corroborated two years later by a mobile cotton broker who returned from a European business trip with a similar tale.

He claimed to have seen Philipe Mororrow in Paris living under the name Pierre Martin but was certain of the man’s identity as they had done business together in Mobile years earlier.

When confronted, the man denied being Maro but fled the broker’s company.

so quickly that he left behind a walking stick with the initials PM engraved on the silver handle.

These reports fueled speculation that Philipe Maro had not died in 1841, that the poisoning had been an elaborate hoax designed to eliminate Delilah, who may have discovered his role in his father’s death.

Some even suggested that the body buried as Filipe might have been that of a servant or business associate who resembled him, though no one could identify who might have disappeared conveniently at that time.

The rumors were troubling enough that in 1856 the city council briefly considered exuming the body buried as Philip Maro.

The measure was defeated after passionate opposition from the remaining Maro relatives and their allies who argued that disturbing the dead would be disrespectful and that the stories were merely sensationalist tales designed to tarnish the family name.

Meanwhile, in Philadelphia, Abram Hollis lived a quiet life of increasing isolation.

City directories from the period list him as a carpenter and later as a cabinet maker with a shop on Lombard Street.

He was known for his exceptional craftsmanship but maintained few social connections.

A census taker in 1860 described him as a solitary man of dignified bearing who speaks little of his past.

The one exception to Abram’s solitude was his friendship with William Still, a prominent black abolitionist and conductor on the Underground Railroad.

Still’s journals mention Abram several times, noting that while he never actively participated in Underground Railroad activities, he provided financial support and occasionally offered temporary shelter in the rooms above his workshop.

In one entry dated August 18th, 1858, still wrote, “Visited with ah today, who continues his solitary existence among his curious wooden birds.

” When I asked why he carves them endlessly, only to give them away to neighborhood children, he replied, “They are messages that never reach their destination.

Perhaps in the hands of the innocent, they might finally find their way.

There is a deep melancholy in him that no passage of time seems to heal.

In the fall of 1861, as the Civil War engulfed the nation, a strange visitor arrived at Abrams Philadelphia shop.

She was an elderly white woman who identified herself only as Madame Moro’s former lady’s companion.

She had tracked Abram through William Still, having learned of their connection through abolitionist circles.

According to a letter Abram later wrote to Still, the woman revealed that she had been present in the Maro household on the morning of Philip’s supposed death and had witnessed something extraordinary.

She claimed that Philipe had not been poisoned at all, but had collapsed from an apparent seizure.

In the confusion that followed, she overheard him whisper instructions to his valet about preparations that needed to be made urgently.

Later that night, she saw light in Philip’s room, a room where a supposedly dead man lay.

She believes, and I’m inclined to agree, Abram wrote to Still, that Philipe seized upon the opportunity presented by his seizure to fake his own death.

Having already planned to flee mobile for reasons unknown, he accelerated his timeline and ensured he would not be pursued by orchestrating a murder charge against Delilah.

Knowing full well that as an enslaved woman accused of poisoning a white man, she would have no chance of a quiddle regardless of evidence.

The visitor had brought with her a small parcel wrapped in faded silk.

Inside was a brooch, a simple oval of silver set with a small pearl that she claimed had belonged to Delilah.

The girl wore it always, hidden beneath her collar.

The woman told Abram, “She said it was a gift from her mother.

Before they took her away, she pressed it into my hand and asked that I find a way to send it to you.

I have carried this burden for 20 years, searching when I could.

Now that I have found you, I can fulfill my promise to her.

” Abram kept the brooch until his death according to the inventory of his personal effects.

It was buried with him alongside the wooden bird in an unmarked grave in Philadelphia’s Lebanon cemetery.

The Civil War brought profound changes to Mobile as it did to all southern cities.

The bustling port became a crucial link in the Confederacy’s supply chain and later a target for Union blockade.

The grand houses were gradually emptied of their finery as resources dwindled.

Some of the city’s wealthiest families fled inland, seeking safety from potential bombardment.

When Union forces finally occupied Mobile in April 1865, the city had already been transformed by years of privation.

The once thriving cotton trade lay in ruins.

Many of the former enslaved population had fled to Union lines during the war.

Others found themselves nominally free but facing uncertain futures in a devastated economy.

Among the Union soldiers who entered Mobile was a young captain named James Hollis from Boston.

Though no direct connection has been established, some historians have speculated that he might have been related to Abram Hollis, perhaps a distant cousin or nephew.

Captain Hollis’s War Diary, preserved in the Massachusetts Historical Society, contains an intriguing entry from April 20th, 1865.

Explored the city today on patrol.

The defeated heir of the place is palpable.

Near the old courthouse, I encountered an elderly colored man who, upon hearing my name, grew quite animated.

He asked if I was related to an Abram Hollis, who had once lived in Mobile.

When I said I did not know of such a relation, the old man’s enthusiasm dimmed, but he proceeded to tell me a remarkable tale of this Abram and a slave woman named Delilah, who were caught up in some scandal involving a prominent family in the 1840s.

The story, as he told it, ended in tragedy, but he insisted that the truth never dies.

It only sleeps until the right time comes.

The passion with which he spoke suggested this was no mere local legend to him, but something he had personal knowledge of.

I pressed him for details, but he grew cautious then, perhaps remembering that despite Union occupation, old habits of silence die hard in these southern cities.

Captain Hollis made several more references to this encounter in subsequent diary entries, noting his attempts to learn more about Abram and Delilah.

He visited the city archives only to find many records from that period had been damaged during the war.

He spoke with a few elderly residents who vaguely remembered the case but offered conflicting details.

Eventually, his unit was reassigned and his investigation ended.

However, his interest had revived local memories of the case.

In 1866, the newly established Daily Mobile Register published a retrospective article titled Justice Miscarried.

The curious case of Delila Maro.

The piece, remarkable for its time, questioned whether Delila had been wrongfully executed, citing doubts about Philip’s death that had persisted for years.

The article prompted a response from Catherine Wells, Philip’s great niece and the last Maro still living in Mobile.

In a letter to the editor, she defended her family’s honor while acknowledging that certain circumstances surrounding my greatuncle’s death have never been satisfactorily explained.

She concluded by announcing her intention to donate all family papers to the historical society so that scholars of the future might make their own determinations based on what fragmentaryary evidence remains.

It was among these donated papers that the most disturbing document related to the case would eventually be found, a small leatherbound journal belonging to Philippe Maro.

Most entries concerned business matters, but several pages had been torn out, leaving just the ragged edges near the binding.

The final intact entry, dated February 18th, 1841, read simply, “It is arranged.

The captain will take me from the north dock on the evening of the 23rd.

By then all obstacles will have been removed.

Father grows weaker by the day.

As for D, her interference cannot be tolerated.

The carpenters’s involvement provides a convenient solution to both problems.

This entry strongly suggested that Philipe had indeed been planning his departure from Mobile and viewed both his father and Delilah as obstacles to be removed.

The reference to the carpenter almost certainly meant Abram Hollis, though how Philipe intended to use him as part of his convenient solution remains unclear.

What is clear is that by February 22nd, Jean Baptiste Maro was dead, Philipe was reportedly poisoned, and Abram and Delilah stood accused of conspiracy and murder, respectively.

The timing aligns too perfectly to be coincidental.

In the summer of 192, an unusual discovery was made during renovation work at the old mobile jail site.

Workers uncovered a small cavity in one of the walls that contained a metal cup with an inscription scratched into its base.

Ah, innocent, February 1841.

The cup was presumably hidden there by Abram during his brief imprisonment before Judge Thompson arranged his escape.

The cup became part of the Mobile Historical Society’s collection where it was displayed alongside other artifacts from the city’s antibbellum period.

For many years, it attracted little attention, just another curiosity from a bygone era.

But in 1921, 80 years after the events in question, the cup gained new significance when a collection of letters was donated to the society by the descendants of Samuel Wilson, the storekeeper who had warned Abram of his impending arrest.

Among these papers was a letter Wilson had written, but apparently never sent to Judge Thompson in March 1841, just days after Delilah’s execution.

In it, Wilson described a conversation he had overheard between Philipe Maro and another man at the coffee house several weeks before the alleged poisoning.

According to Wilson’s account, Philipe had been discussing the effects of various toxic substances and how they might be detected.

The other man, whose name Wilson didn’t know, had advised Philipe that certain plant-based toxins were nearly impossible to trace if administered gradually.

Wilson wrote that he had not made the connection at the time but realized its significance only after Jean Batist’s death and the subsequent events involving Phipe Delilah and Abram.

He explained that he had hesitated to come forward earlier out of fear of repercussions.

Phipe being a powerful man in mobile society.

By the time he overcame his reluctance, Delilah had already been executed and Abram had fled the city.

I write now, Wilson concluded, because I can no longer bear the weight of my silence.

I believe that Philipe Maro poisoned his father over time, was discovered by the girl Delilah, and engineered an elaborate scheme to silence her and divert suspicion from himself.

that an innocent woman has been executed and an innocent man forced into exile is a stain upon our city and our justice system that can never be removed.

I leave this testimony in your hands, Judge Thompson, to use as your conscience dictates.

Whether Judge Thompson ever received this letter is unknown.

If he did, he apparently chose not to act on it.

perhaps believing that reopening the case would serve no purpose now that Delila was dead and Abram gone.

The full truth of what happened in the Maro household in February 1841 may never be known with certainty, but the weight of evidence discovered in the decades since strongly suggests that Philip Maro orchestrated an elaborate deception that cost Delila her life, drove Abram into exile, and allowed Phipe to escape with his father’s fortune.

The final piece of this historical puzzle emerged in 1967 when renovations to an old building in Marseilles uncovered a hidden compartment containing personal papers and a substantial amount of gold coin.

Among the papers was a French passport issued in 1841 to1 Pierre Marta whose physical description matched that of Philip Maro.

Also found was a letter addressed to Catherine, presumably the great niece who had donated the family papers to the Mobile Historical Society.

The letter dated 1864 but never sent contained a partial confession.

You have never known the truth of my departure from Mobile, nor the circumstances that necessitated it.

know that I did not die that day in 1841, though many believe I did.

The body buried under my name was that of a sailor who resembled me sufficiently in build and feature to serve my purpose.

He had died of natural causes the night before, a fact that my physician, generously compensated for his discretion, was willing to overlook.

As for the girl Delilah, she was indeed innocent of my murder, but guilty of a greater crime in my eyes.

She had discovered my role in father’s declining health.

Her connection to the carpenter Hollis provided a convenient means of discrediting any accusations she might make.

I never intended for her to die, merely to be sold away where her stories would not be believed.

that events escalated beyond my control is a regret I have carried these 23 years.

I write this not to seek absolution which I know is beyond reach but to unbburden myself of secrets too long kept.

Whether this letter ever reaches you depends on my courage in sending it which like so much of my courage may prove inadequate.

The letter was signed Philip Morrow now and forever.

Pierre Martin.

French records indicate that Pierre Martan died in Marseilles in 1865.

His substantial estate passing to distant relatives as he had no children.

When news of this discovery reached Mobile, it caused a minor sensation.

The Mobile Register ran a front page story under the headline century old mystery solved.

Philipe Maro’s deception revealed.

The article detailed the evidence suggesting that Phipe had faked his death, framed Delilah, and fled to France with his inheritance, leaving a trail of injustice behind him.

In response to this revelation, the city council passed a resolution in 1968, formally acknowledging that Delila Maro had been wrongfully executed.

A small plaque was installed near the site of the old courthouse where her trial had taken place commemorating her as a victim of a miscarriage of justice.

For many in Mobile, especially in the African-American community, this belated acknowledgement was insufficient.

In 1969, a group of civil rights activists and historians formed the Delila Maro Justice Committee dedicated to researching her case and similar historical injustices.

Their efforts led to the publication of a book, Silenced Voices: The Delilah Maro Case and the Legacy of Injustice in Mobile, which placed her story in the broader context of the legal systems historical mistreatment of enslaved people and free black citizens.

The book became required reading in several university history courses and sparked renewed interest in the case.

In 1972, archaeologists conducting a survey at the site of the old city cemetery discovered an unmarked grave that based on its location and period likely contained Delila’s remains.

After careful consideration and consultation with community leaders, it was decided not to disturb the grave, but to mark it with a simple headstone bearing her name, and the inscription, “Truth comes to light at last.

” The story of Abram Hollis and Delila Maro has since become an integral part of Mobile’s historical narrative, a cautionary tale about the human cost of slavery, prejudice, and corruption.

Tours of Historic Mobile now include their story, acknowledging the darker aspects of the city’s past rather than glossing over them.

In 2003, a descendant of Abram Hollis’s Philadelphia neighbors, an elderly woman named Margaret Powell, contacted the Mobile Historical Society with an extraordinary item, a small wooden bird intricately carved from cypress wood.

According to family law, it had been given to her great grandmother by a dignified colored gentleman who made beautiful furniture in the 1860s.

The bird matched the description of the carvings Abram had created as signals for Delila.

It was added to the historical society’s collection, displayed alongside the metal cup from the jail, the brooch found in Abram’s grave, which had been exumed when the Lebanon cemetery was relocated in the 1930s, and a copy of Philip’s damning journal entry.

Together, these artifacts tell a story of love across impossible barriers, of treachery and injustice, of lives destroyed and truth long delayed.

They remind us that history is not merely a collection of dates and events, but a tapestry of human experiences with all their complexity, tragedy, and occasional transcendence.

As for the persistent rumors of ghostly phenomena associated with the case, the scent of time on Government Street, the shadowy figure seen near the cathedral at dawn, the inexplicable cold spots in buildings connected to the Maro family.

They belong to the realm of folklore rather than history.

Yet they speak to the power of this story to capture the imagination and to the sense that some injustices are so profound that they leave an imprint on the world that cannot be easily erased.

In the end, the story of Abram Hollis and Delila Maro is one of secrets gradually revealed, of truth emerging fragment by fragment across generations.

It reminds us that the past is never truly past, that its currents continue to shape our present in ways both visible and hidden.

The final word on their story comes from a poem found among Abram Hollis’s possessions after his death, written in a careful hand on yellowed paper.

Whether he composed it himself or copied it from somewhere else is unknown, but its sentiments seem to capture the essence of his and Delilah’s tragic connection.

Time, they say, heals all wounds, yet some cuts go deeper than time can reach.

I carry your memory like a shadow, present even in darkness, inseparable from myself.

They took from us our chance at life together, but they could not take the truth of what we were.

that remains a flame no prison can contain.

A light no gallows can extinguish.

Perhaps in some other lifetime, some kinder world we will meet again where no barriers stand between us.

Until then, I send these wooden birds as my messengers, carrying all the words I never had the chance to say.

Today, in Mobile’s historic district, where the past and present coexist in an uneasy truce, visitors sometimes report a strange phenomenon.

In the early morning hours, when fog rises from the mobile river and shrouds the old streets in mist, they say two figures can occasionally be glimpsed walking hand in hand.

A tall man in the simple clothes of a craftsman, and a young woman whose dignity shines through her servant’s attire.

They appear briefly, then vanish as the sun burns away the fog.

Like much of their story, this reported sighting exists at the intersection of fact and legend, of history and imagination.

But in a sense, it hardly matters whether such apparitions are real or merely the product of minds primed by a powerful narrative.

What matters is that the story of Abram Hollis and Delila Maro continues to be told.

That their voices, silenced in life, echo still through the corridors of time.

Their story reminds us of the human capacity for both cruelty and courage, for deception and enduring love.

It speaks to the long, slow arc of justice that sometimes takes generations to complete its course.

And it affirms that while truth may be temporarily suppressed, buried or disguised, it possesses a stubborn persistence that eventually brings it to light.

In the archives, in the artifacts, in the stories passed down through generations, Abram and Delilah live on two souls who found each other against impossible odds, whose brief connection ignited a chain of events that would eventually expose a carefully constructed lie and bring a measure of postumous justice.

Their story, once whispered, is now proclaimed.

Their truth once buried, has been unearthed.

And somewhere perhaps they walk together still through the mist shrouded streets of Mobile, finally free of the constraints that bound them in life, their story complete at last.

News

✈️ U.S. F-15 FIRST STRIKE — ALLEGED CARTEL DRUG LAB ERASED IN SECONDS AS SKY ERUPTS IN A BLINDING FLASH ✈️ What officials described as a precision operation turned the night into daylight, with jets screaming overhead and a suspected production site reduced to smoking rubble in moments, sending a shockwave across the region and a message that the airspace above is no safe haven for hidden empires 👇

The Last Fortress: A Shocking Revelation In the heart of the Mexican jungle, Diego stood at the entrance of the…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: FBI & ICE SHATTER ALLEGED TRUCKING NETWORK WITH SOMALI TIES — 83 ARRESTED, $85M IN CASH AND WEAPONS STACKED AS EVIDENCE 🚨 Before sunrise, federal agents swept through depots and dispatch offices, hauling out duffel bags of currency and seizing firearms while stunned neighbors watched a logistics operation authorities claim was hiding a sprawling criminal enterprise behind everyday freight routes 👇

The Shadows of the Ghost Fleet In the heart of the Midwest, where the snow fell like a blanket over…

🚨 FBI & ICE STORM GEORGIA “CARTEL HIDEOUT” — GRENADE LAUNCHER DISCOVERED AND $900K IN DRUGS SEIZED IN A DAWN RAID THAT SHOCKED THE BLOCK 🚨 What neighbors thought was just another quiet morning exploded into flashing lights and tactical vests as agents swept the property, hauling out weapons and evidence while officials described a months-long investigation that culminated in a swift, coordinated takedown 👇

The Unraveling of Shadows: A Tale of Betrayal and Redemption In the heart of Jackson County, Georgia, the air was…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: DEA & FBI CRUSH ALLEGED CARTEL TRUCKING EMPIRE — HIDDEN ROUTES MAPPED, DRIVERS DETAINED, AND MILLIONS STACKED AS EVIDENCE 🚨 Before sunrise, highways turned into a grid of flashing lights as agents intercepted rigs, cracked open trailers, and traced coded dispatch logs, revealing what officials describe as a logistics web hiding in plain sight behind ordinary freight lanes 👇

The Fall of Shadows: A Cartel’s Empire Exposed In the dimly lit corridors of power, where shadows danced with deceit,…

🚢 U.S. NAVY TRAPS SINALOA CARTEL’S ALLEGED $473 MILLION “DRUG ARMADA” AT SEA — AND THE HIGH-STAKES STANDOFF UNFOLDS UNDER FLOODLIGHTS AND ROTOR WASH 🚢 Radar screens lit up, cutters boxed in fast boats, and boarding teams moved with clockwork precision as authorities described a sweeping maritime interdiction that turned open water into a chessboard, stacking seized cargo on deck while prosecutors hinted the ripples would travel far beyond the horizon 👇

The Abyss of Deceit: A Naval Reckoning In the heart of the Caribbean, where the turquoise waters glimmered under the…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: DEA & FBI DESCEND ON MASSIVE TEXAS LOGISTICS HUB — 52 TONS OF METH SEIZED AS 20 POLITICIANS ALLEGEDLY TIED TO A SHADOW NETWORK ARE THRUST INTO THE SPOTLIGHT 🚨 What began as a quiet federal probe detonated into a sweeping raid of warehouses and boardrooms, with agents hauling out towering stacks of evidence while stunned insiders whisper that the real shockwave isn’t just the drugs — it’s the powerful names now facing intense scrutiny 👇

Shadows of the Underground: The Texas Cartel Unveiled In the heart of Texas, where the sun sets over sprawling landscapes,…

End of content

No more pages to load