Welcome to this journey through one of the most disturbing cases recorded in the history of the United States.

Before we begin, I invite you to leave in the comments where you’re watching from and the exact time you’re listening to this narration.

We’re interested in knowing what places and what times of day or night these documented stories reach.

In the autumn of 1867, the small town of Milfield, nestled in the Shannondoa Valley of Virginia, was still reeling from the aftermath of the Civil War.

The once prosperous community had fallen into disrepair, with many of its buildings bearing the scars of conflict.

Among these stood the Caldwell Merkantile, a three-story brick building on the corner of Elm Street and River Road that had somehow survived the years of fighting relatively unscathed.

Josephine Caldwell became the proprietor of this establishment following the death of her husband, Harold, who had passed away under circumstances that raised quiet questions among the town’s people.

According to county records, Harold Caldwell died of heart failure at the age of 43 in the winter of 1865, just as the war was drawing to its bloody close.

But those who frequented the local tavern told a different story, one of a marriage that had grown cold, of harsh words exchanged behind closed doors, and of a woman who seemed almost relieved when she dawned the black crepe of widowhood.

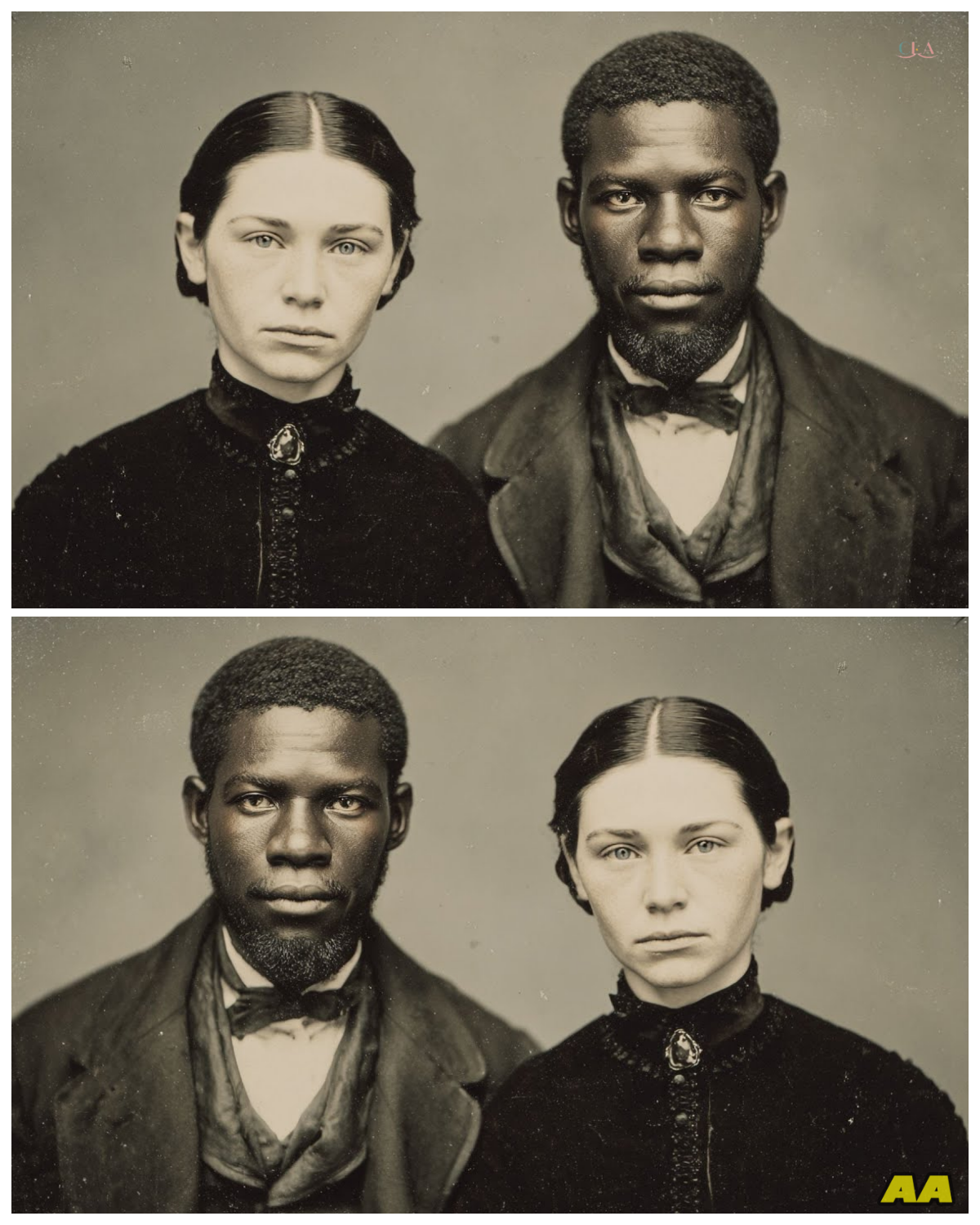

At 37 years of age, Josephine was known throughout Milfield for her sharp mind and sharper tongue.

The ledgers discovered years later in the attic of the merkantile revealed a woman with a meticulous attention to detail, recording every transaction down to the last penny.

Those who conducted business with her described a handsome woman with piercing blue eyes and dark hair, always pulled back in a severe bun, not a strand out of place.

She wore her widow’s weeds with such distinction that some said it seemed as though she had been born to wear black.

“I have no interest in remarrying,” she was reported to have told Mrs.

Elellanena Wittman, the wife of the town’s doctor, during a tea gathering in the spring of 1867.

Love is a merchant’s worst enemy.

It clouds the mind and empties the purse.

According to Mrs.

Wittman’s journal found decades later during a renovation of the old Wittman residence, Josephine had laughed after making this statement, a sound described as hollow as an empty well.

The merkantile prospered under Josephine’s management.

While other businesses struggled in the difficult years after the war, the Caldwell Merkantile expanded its inventory and clientele.

It was said that Josephine extended credit to those truly in need, but was ruthless in collecting debts when they came due.

The basement of the store, according to town records, was used for storage, primarily of dry goods and canned preserves that needed to be kept cool.

Only Josephine and her longtime employee, a man named Isaiah Turner, were permitted to access this lower level.

Isaiah Turner was something of an enigma in Milfield.

He had arrived in town in the early summer of 1866, a tall, broadshouldered man with a pronounced limp and hands that bore the calluses of hard labor.

According to employment records found in the county archives, Isaiah had been hired by Josephine within a week of his arrival in town.

He was 32 years old at the time, unmarried, and gave little information about his past, beyond stating he had served in the Union Army during the war.

This last detail alone would have made him unwelcome in many establishments in Virginia at that time, but Josephine Caldwell seemed unconcerned with such matters.

I care only that he can count accurately and lift what I cannot,” she reportedly told the town gossip, who questioned her decision to hire a former Union soldier.

The fact that Isaiah was also a freed slave who had fought for the North made his position all the more unusual in postwar Virginia.

What transpired between Josephine Caldwell and Isaiah Turner over the following months would later become the subject of intense speculation and investigation.

According to the journal of Thomas Abernathy, the town’s postmaster, Isaiah was observed entering the merkantiel before dawn and leaving well after sunset almost every day.

He took his meals there and on several occasions was seen carrying bundles of Josephine’s laundry to and from the washerwoman on Green Street.

By the winter of 1867, rumors had begun to circulate among the town’s people.

Some claimed to have heard strange noises coming from the merkantile late at night.

the sound of furniture being moved, muffled conversations, and once, according to the widow apprentice who lived across the street, a cry that could have been pain or pleasure, though I dare not speculate which.

It was during this time that several items went missing from homes in Milfield.

Nothing of significant value.

a silver letter opener from Judge Wilson’s desk, a brass key from the miller’s front hall, an antique thimble from Mrs.

Apprentice’s sewing basket.

The constables reports indicate that these thefts were reported but never solved, deemed too trivial to warrant a thorough investigation in a time when more serious crimes demanded attention.

On the evening of December 20th, 1867, a severe snowstorm descended upon the Shenandoa Valley.

According to meteorological records preserved in the University of Virginia archives, this was one of the worst winter storms to hit the region in decades.

The temperature dropped well below freezing, and by morning, Milfield was buried under more than 2 ft of snow.

It was during this storm that Isaiah Turner disappeared.

According to statements given to Constable Frederick Jenkins documented in his official report dated January 3rd, 1868, Isaiah had been seen entering the merkantiel at approximately 4:00 in the afternoon on December 20th, just as the snow was beginning to fall in earnest.

This was the last time anyone other than Josephine Caldwell would report seeing him alive.

When questioned about Isaiah’s absence in the days following the storm, Josephine reportedly told concerned towns people that he had decided to travel north to visit family in Pennsylvania for the Christmas holiday.

This explanation was accepted by most, though some noted that it seemed strange for a man to undertake such a journey in the midst of a blizzard.

As weeks passed, with no word from or about Isaiah, people began to talk.

According to the diary of Reverend George Harmon, dated February 10th, 1868, parishioners had begun to express concerns about the nature of the relationship between Josephine and her employee.

There are whispers of an inappropriate attachment, the Reverend wrote, though none dare speak such accusations aloud for fear of Mrs.

Caldwell’s influence in the town.

The merkantil continued to operate with Josephine now handling all aspects of the business herself.

Those who traded with her during this period described her as unusually subdued, her customary sharpness blunted by what appeared to be fatigue.

The ledgers from this time preserved in the county historical society show uncharacteristic errors in calculation and inventory.

Small mistakes that nonetheless seem significant given Josephine’s previous precision.

In late March of 1868, nearly 3 months after Isaiah’s disappearance, an incident occurred that would eventually lead to the discovery of what had truly transpired during that December snowstorm.

According to the account of Dr.

Walter Wittmann, he was called to the merkantile on the evening of March 25th to attend to Josephine, who had apparently collapsed while tallying the day’s receipts.

Upon his arrival, Doctor Wittman found Josephine in a state of delirium, burning with fever.

As he attempted to treat her, she reportedly began to speak in disjointed sentences, references to the basement, to chains, and to something she called our masterpiece.

The doctor’s notes found among his papers after his death in 1872 indicate that he initially attributed these ramblings to the fever, but became concerned enough to mention them to Constable Jenkins the following day.

The constable, according to his official report dated March 27th, 1868, decided to conduct a cursory inspection of the Merkantile’s basement while Josephine was confined to her bed under the doctor’s care.

What he found there would shock the entire community of Milfield.

The basement, accessed via a narrow staircase behind a door that was usually kept locked, was divided into several rooms.

The main area contained the expected inventory, barrels of flour and sugar, crates of canned goods and other merchandise.

But a smaller room hidden behind a false wall of shelving contained something altogether different.

According to the constable’s detailed report, this hidden room measured approximately 10 ft x 12 ft and contained a cot, a small table, and a chamber pot.

Iron rings were bolted to the stone wall with heavy chains attached that showed signs of recent use.

On the table lay a leatherbound journal, its pages filled with writing in two distinct hands, one firm and precise, the other larger and less controlled.

The journal, excerpts of which were included in court documents, later sealed by order of Judge Wilson, allegedly contained a detailed account of what Josephine Caldwell described as our experiment in the boundaries of devotion.

According to those who claimed to have seen these documents before they were sealed, the journal detailed a relationship that had begun as employer and employee, but had evolved into something far more complex and disturbing.

Isaiah Turner, it seemed, had not left for Pennsylvania at all.

The journal entries suggested that he had willingly entered into an arrangement with Josephine, wherein he would be periodically confined to the hidden room in the basement, sometimes for days at a time, as part of what was described as a mutual exploration of the limits of control and surrender.

Most disturbing to those who read these accounts was the apparent evolution of this arrangement.

Later entries in the journal, reportedly written in Josephine’s hand, described Isaiah’s increasing reluctance to continue their sessions and her own growing obsession with maintaining what she called our special connection.

The final entry in the journal, dated December 21st, 1867, the day after the snowstorm began, contained only a single sentence.

He sought to leave me as they all do, but now he shall remain forever.

A search of the merkantiles.

Basement expanded to include areas behind walls and beneath floorboards yielded no trace of Isaiah Turner.

What had perhaps begun as a consensual, if unusual, relationship between two adults had gradually taken on darker dimensions.

However, when investigators examined the large cast iron stove that heated the main floor of the store, they discovered among the ashes what appeared to be fragments of bone and metal, specifically what the town blacksmith identified as pieces of chain similar to those found in the hidden room.

Josephine Caldwell never stood trial for whatever fate befell Isaiah Turner.

On April 2nd, 1868, while still under house arrest at her residence above the Merkantile, she died of what Dr.

Wittmann diagnosed as brain fever.

In his medical report preserved in the county records, the doctor noted that in her final hours, Josephine had been heard repeatedly murmuring, “He mocked my chains, but love forged stronger ones.

” The Caldwell Merkantile was sold later that year to a family from Richmond who knew nothing of its history.

The hidden room in the basement was sealed up, its entrance concealed behind new shelving.

For many years, employees and customers of what became known as the River Road General Store reported unusual cold spots in certain areas of the main floor, particularly near the large stove that continued to heat the building until it was eventually replaced with more modern heating in the early 1900s.

In 1924, during renovations to the building’s foundation, workers discovered a small metal box embedded in the basement wall.

According to an article published in the Milfield Gazette on June 12th of that year, the box contained several personal items.

A silver letter opener, a brass key, an antique thimble, and a gold wedding band that records indicated had belonged to Harold Caldwell.

Also in the box was a dgera type photograph showing a stern-faced woman in widow’s weeds standing behind a seated man whose face had been carefully scratched out of the image.

The building that once housed the Caldwell Merkantile still stands on the corner of Elm Street and River Road in Milfield, Virginia.

It has been many things over the years.

A hardware store, a restaurant, and most recently a boutique selling locally made crafts.

Current owner Margaret Holland claims no knowledge of the building’s history, though she did mention in a 1968 interview with a graduate student researching local architecture that something about the basement makes me uneasy.

I avoid going down there whenever possible.

In that same year, during an unusually cold December, a construction worker renovating the building’s heating system reported finding what appeared to be a partial handprint seared into the brick surrounding the old chimney, as if someone had pressed their palm against the hot surface and held it there despite the pain.

According to his statement to the local historical society, the case of Josephine Caldwell and Isaiah Turner was largely forgotten by the 1970s, relegated to the dusty archives of the county courthouse and the occasional whispered story told by the older residents of Milfield.

Perhaps this is for the best.

Some secrets, like the true nature of what transpired in the basement of the Merkantile during that snowstorm in 1867, are better left buried in the past.

What is known with certainty is this.

Josephine Caldwell, who once mockingly declared that love was a merchant’s worst enemy, appears to have discovered a different kind of attachment, one that consumed her so completely that it ultimately destroyed both her and the man who became the object of her obsession.

The chains that were found in that hidden room may have been physical, but the bonds that truly bound these two individuals were forged from something far more complex and dangerous.

To this day, some residents of Milfield claim that on particularly cold winter nights, when the wind blows down from the Shannondoa mountains and snow begins to fall, the faint sound of chains can be heard rattling in the vicinity of the old merkantile building.

Others insist that on the anniversary of that terrible snowstorm, the figure of a limping man can sometimes be glimpsed through the windows of the former store, moving between the shelves as if still performing his duties from more than a century ago.

Perhaps these are merely the embellishments that naturally acrew to any local tragedy over time.

Or perhaps they speak to a truth that the official records with their clinical descriptions and careful emissions failed to capture.

That some attachments transcend even death, binding those involved in patterns that repeat endlessly through the years.

The journals that might have provided more insight into the minds of Josephine Caldwell and Isaiah Turner were reportedly destroyed in a courthouse fire in 1952.

along with many other documents related to the case.

All that remains are fragments of the story preserved in various archives and personal papers like pieces of a puzzle that can never be completely assembled.

What is perhaps most disturbing about this case is not what we know but what remains unknown.

The true nature of the relationship between these two individuals, what drew them together and what ultimately drove them to their tragic end can only be speculated upon.

Like so many historical mysteries, the case of the merchant’s widow and her employee has no neat resolution, no satisfying conclusion that explains away the darkness at its core.

In a letter discovered in 1961 during the demolition of the old Wittmann residence, Dr.

Walter Wittmann wrote to his brother in Boston, “I have seen many disturbing things in my years as a physician, but none has troubled my sleep as much as what was found in the basement of the Caldwell Merkantile.

It is not the evidence of physical cruelty that haunts me, but rather the glimpse it provided into the depths to which the human heart can sink when obsession masquerades as love.

I fear I shall never understand it, though perhaps that is a blessing.

The town of Milfield has changed much in the century and a half since these events took place.

The scars of the Civil War have faded.

New buildings have risen where old ones stood, and generations have come and gone.

Yet the story of Josephine Caldwell and Isaiah Turner persists, passed down through the years as a cautionary tale about the dangers of isolation, obsession, and the dark paths down which the human mind can wander when left to its own devices.

For those who study such cases, the tragedy at the Coldwell Merkantile serves as a reminder that the most terrifying monsters are not supernatural creatures from beyond the grave, but ordinary people whose minds have turned in on themselves, transforming natural human emotions into something twisted and destructive.

As for the spirits that some claim still haunt the corner of Elm Street and River Road, whether they exist or not, matters less than what they represent.

The enduring power of a story that speaks to our deepest fears about the nature of love, possession, and the thin line that sometimes separates the two.

In the end, perhaps the most chilling aspect of this story is how unremarkable both Josephine Caldwell and Isaiah Turner appeared to their neighbors and acquaintances.

They were, by all accounts, simply a widow running her late husband’s business, and the employee who helped her do so.

That something so dark could fester beneath such an ordinary surface reminds us that we can never truly know what lies in the hearts and minds of those around us or indeed within ourselves.

The merchants’s widow who once mocked the idea of love discovered in the end a different kind of attachment, one forged not of tenderness and mutual respect, but of obsession and control.

The chains that were found in that hidden room were perhaps merely physical manifestations of the invisible bonds that had come to define their relationship.

Bonds that proved stronger and far more deadly than either of them could have anticipated.

As winter descends once more upon the Shenandoa Valley, and snow begins to fall on the old building that once housed the Caldwell Merkantile, one cannot help but wonder, do they remain there still, locked in their eternal struggle? And if so, which is truly the prisoner and which the jailer? Some questions perhaps are better left unanswered.

In the shadows of history, in the gaps between what is documented and what is forgotten, stories like that of Josephine Caldwell and Isaiah Turner continue to resonate because they speak to something fundamental about human nature.

Our capacity for both connection and cruelty for love and its darker twin obsession.

That these capacities exist within all of us is perhaps the most disturbing truth of all.

The sound of chains, whether real or imagined, serves as a reminder of the bonds we forge in life, some that lift us up and others that ultimately drag us down into darkness.

For Josephine Caldwell, who once mocked the very idea of love, that sound became both her triumph and her undoing.

And for those who hear it still on cold winter nights in Milfield, Virginia, it remains a warning that echoes through the years.

Be careful what you chain to your heart, for you may find yourself bound as well.

The sound of chains, whether real or imagined, serves as a reminder of the bonds we forge in life, some that lift us up and others that ultimately drag us down into darkness.

For Josephine Caldwell, who once mocked the very idea of love, that sound became both her triumph and her undoing.

And for those who hear it still on cold winter nights in Milfield, Virginia, it remains a warning that echoes through the years.

Be careful what you chain to your heart, for you may find yourself bound as well.

In 1963, a graduate student from the University of Virginia named Elizabeth Montgomery came to Milfield researching 19th century commerce in the Shenondoa Valley.

According to her notes, discovered among her personal effects after her death in 1968, she spent several days examining the town’s archives and interviewing elderly residents.

Her research led her to the former Caldwell Merkantile, where she reportedly requested permission to examine the basement.

The owner at that time, a man named Howard Jenkins, was initially reluctant, but eventually agreed to accompany her.

According to Jenkins statement to the Milfield Historical Society recorded in 1965, they discovered a section of the basement wall where the bricks appeared newer than the surrounding masonry.

Upon closer inspection, Montgomery insisted she could see what looked like scratches on the older bricks, as if someone had tried to claw their way out, Jenkins recalled her saying.

Montgomery’s research notes indicate that she became increasingly obsessed with the Caldwell Turner case.

She spent hours in the county courthouse reviewing what few documents had survived and sought out descendants of those who had lived in Milfield during the 1860s.

Most disturbing were her final journal entries in which she described experiencing what she called a presence in her rented room at the local boarding house.

I feel as though I am being watched, she wrote on April 18th, 1963.

Last night, I dreamed of a woman in black standing at the foot of my bed.

She said nothing, but I understood that she was warning me to stop my research.

When I awoke, my hands were clenched so tightly that my nails had drawn blood from my palms.

2 days later, Montgomery abruptly terminated her research and left Milfield.

According to the boarding house proprietor, she departed in such haste that she left behind several personal items, including a silver letter opener that she had purchased at an antique shop in town, an item that, according to the shop’s records, had once belonged to Judge Wilson, one of the officials who had investigated the Caldwell case.

Montgomery returned to the university, but never completed her thesis.

Her academic advisor, Professor James Harrington, noted in a letter to her parents following her death that she had become withdrawn and paranoid in the weeks after her return from Milfield.

She spoke of being followed, of hearing the sound of chains at night, and of a woman’s voice whispering in her ear when she was alone.

Elizabeth Montgomery was found dead in her apartment on December 20th, 1963, exactly 96 years to the day after the disappearance of Isaiah Turner.

The official cause of death was listed as suicide, though the circumstances were unusual enough to warrant special mention in the coroner’s report.

Her wrists bore what appeared to be ligature marks as if they had been bound tightly, though no restraints were found in the apartment.

Most disturbing was the discovery that she had apparently used a piece of chain to hang herself.

Chain that, according to police reports, did not match any found in her apartment or belongings.

In a sealed envelope discovered among her effects, was a final journal entry dated the day of her death.

It read simply, “She has found me.

” She says, “I remind her of him.

I cannot escape her chains.

The death of Elizabeth Montgomery might have been dismissed as the tragic end of a troubled young woman were it not for what happened 5 years later.

” In 1968, during renovations to the building that had once housed the Caldwell Merkantile, workers breaking through the section of newer brick work in the basement discovered a sealed chamber.

Inside, according to the official report filed with the Milfield Police Department, they found human remains.

The bones examined by forensic anthropologists from the state medical examiner’s office were determined to belong to an adult male approximately 30 to 40 years of age of African descent.

The remains showed signs of prolonged malnutrition and evidence of healed fractures consistent with injuries that might have been sustained in combat.

Most significant was the pronounced deterioration of the right hip joint, which would have caused the individual to walk with a noticeable limp.

Also discovered with the remains were several lengths of chain, a pocket watch bearing the initials it, and most disturbing of all, a journal.

The pages of this journal had largely deteriorated due to moisture in the sealed chamber, but certain passages remained legible.

According to those who examined the document before it was sealed by court order, these passages detailed the final days of Isaiah Turner.

December 21st, 1867.

The storm rages outside.

She has locked the door and taken the key.

I told her today that I could no longer continue our arrangement, that I had accepted a position in Philadelphia and would be leaving after Christmas.

She laughed in that hollow way of hers and said, “No one leaves me, Isaiah.

” Not my husband and certainly not you.

Another passage apparently written some days later read, “I do not know how long I have been here.

The food she brings is barely enough to keep me alive.

When I ask why she is doing this, she says only that I belong to her now, that I’m the only one who understands her true nature.

She sits for hours watching me, writing in her own journal.

Sometimes she reads aloud what she has written terrible things about love and possession.

I fear for my life.

The final entry, its script shaky and barely legible, simply stated, “She came today with the chains heated in the fire, said she would mark me as hers forever.

God help me.

” The discovery of Isaiah Turner’s remains and journal caused a brief sensation in Milfield, but the story was quickly suppressed.

According to local newspaper archives, the town council voted to have the remains quietly buried in the county cemetery with no marker to indicate who lay there or the circumstances of their death.

The journal was sealed by court order and placed in the county archives where it reportedly remained until the courthouse fire of 1952.

But the story refused to stay buried.

In the decades that followed, multiple owners of the building reported strange occurrences, unexplained cold spots, the sound of chains rattling in the night, items moved from where they had been left.

Several attempted renovations of the basement were mysteriously abandoned with workers refusing to return after experiencing what one described as a feeling of being watched by someone filled with rage.

In 1982, during another attempt to renovate the basement, workers discovered a small recess behind the chimney.

Inside was a metal box containing what appeared to be a woman’s wedding ring.

Several buttons cut from a Union Army uniform and a dgeraype photograph of a stern-faced woman standing beside a seated black man whose expression was solemn but dignified.

On the back written in a firm, precise hand were the words JC and it some bound forever.

The current owner of the building, as of 1968, had converted the main floor into a small museum dedicated to the history of Milfield with a special exhibit focused on the Civil War era.

Curiously absent from this exhibit was any mention of Josephine Caldwell or Isaiah Turner, despite the significant role the Merkantile had played in the town’s commercial development.

When questioned about this omission by a reporter from the Richmond Times Dispatch in 1965, the owner, Martin Hollister, reportedly replied, “Some stories are better left untold.

” According to the reporter’s notes, Hollister then added, almost as an afterthought, “Besides, she doesn’t like us talking about him.

” When asked to clarify this statement, Hollister claimed he had been misunderstood.

The museum closed its doors permanently 6 months later with Hollister citing personal reasons for the decision.

He and his family left Milfield shortly thereafter, leaving the building vacant for several years.

In 1967, exactly 100 years after the disappearance of Isaiah Turner, a fire broke out in the old Merkantile building.

Despite the efforts of the Milfield Volunteer Fire Department, the structure was severely damaged.

During the subsequent demolition, workers discovered something unusual in the ruins of the basement.

A small room with walls of newer brick that had somehow survived the fire intact.

Inside this room, according to the foreman’s report, they found a small table on which sat a leatherbound journal and an antique pen.

The journal was open to a blank page, and the pen appeared to have been recently used, though the building had been vacant for years.

Most disturbing of all was what appeared to be fresh ink on the page, a single line of text in a firm, precise hand.

Love wears many faces.

Some of them wear chains.

The journal disappeared from the work site that night.

The foreman, when questioned, claimed no knowledge of what had happened to it.

He resigned his position the following day and left Milfield, reportedly telling his wife, “Some things are better left buried in the ashes.

” The lot, where the Caldwell Merkantile once stood, remained vacant for many years, with various development proposals mysteriously falling through.

Local rumors suggested that Josephine Caldwell’s influence somehow persisted, preventing any new construction on the site of her former business and the scene of her dark obsession.

In 1968, the town council finally approved a plan to convert the empty lot into a small park.

During the groundbreaking ceremony, the mayor’s young daughter reportedly asked, “Daddy, who is that lady in the black dress watching us?” When her father turned to look, he saw nothing, but several other attendees claimed to have felt a sudden cold breeze despite the warmth of the summer day.

The park was completed, but locals noted that few people chose to linger there, especially after sunset.

Children would run through on their way to and from school, but never stopped to play.

Dogs being walked along its paths would often growl or whine, pulling at their leashes to leave.

In the center of the park stands a small plaque dedicated in 1968 that reads simply in memory of those who lived, worked, and suffered here.

May they find the peace in death that eluded them in life.

No names are mentioned, no specific events commemorated.

Yet each year on December 20th, someone places a single black rose and a length of chain beside this marker.

The story of Josephine Caldwell and Isaiah Turner serves as a reminder of the darkest aspects of human nature.

How love can transform into obsession.

How the desire for connection can become a need to possess.

And how the chains we forge in life can bind us even beyond death.

For the residents of Milfield who know the tale, the corner of Elm Street and River Road remains a place to hurry past rather than linger.

And on cold winter nights, when the wind blows down from the mountains and snow begins to fall, some claim they can still hear the sound of chains rattling in the darkness and the echo of a woman’s hollow laughter.

The true horror of what transpired between Josephine Caldwell and Isaiah Turner lies not in supernatural elements or graphic violence, but in the very human capacity for obsession and cruelty.

It reminds us that sometimes the most dangerous chains are not those made of iron, but those forged from distorted emotions.

Chains that combined both the captor and the captive in patterns of destruction from which neither can escape.

In the archives of the University of Virginia, there exists a fragment of what is believed to be Isaiah Turner’s journal, preserved by a librarian who rescued it from the courthouse before the fire of 1952.

The passage dated approximately 1 month before his disappearance reads, “Today, Mrs.

Caldwell said something that chilled me to the bone.

We were discussing a customer who had failed to repay his debt, and she remarked, “All debts must be paid, Isaiah.

” One way or another.

When I asked what she meant, she smiled in that way of hers and said, “When someone tries to leave you with accounts unsettled, you simply must find a way to keep them close until balance is restored.

” I fear there is a darkness in her that grows deeper with each passing day.

Perhaps the most unsettling aspect of this story is how ordinary it began with two lonely people seeking connection in a world that offered them few options.

That their relationship evolved into something so twisted speaks to the fine line between love and obsession, between the desire for closeness and the need to possess.

In death, as in life, Josephine Caldwell and Isaiah Turner remain bound together.

Their story, a cautionary tale whispered by parents to warn children away from the park on the corner of Elm Street and River Road.

Their spirits, whether real or imagined, a reminder of passions that consumed rather than comforted.

The merchants’s widow, who once mocked the idea of love, discovered in the end a twisted version of it that she carried with her to the grave and perhaps beyond.

and Isaiah Turner, who sought only employment and perhaps human connection in a hostile post-war world, found himself ins snared in chains, both literal and figurative, from which not even death could free him.

In 1968, exactly 100 years after the death of Josephine Caldwell, a researcher from the Virginia Historical Society visited Milfield to examine what few records of the case remained.

According to her report filed in the society’s archives, she spent several hours in the park that now occupies the site of the former merkantile.

As she was preparing to leave, she noted a sudden drop in temperature and the distinct sensation of being watched.

In her journal that evening she wrote, “I cannot shake the feeling that I have disturbed something that was better left at rest.

While sitting on a bench in the park today, I distinctly heard a woman’s voice whisper, “He is mine.

They are all mine.

” When I turned, no one was there, but on the ground beside me lay a small brass button of the type once used on Union Army uniforms.

The researcher departed Milfield the following day, leaving her work unfinished.

In a letter to her supervisor, she wrote only, “Some chains are better left unexamined.

” And so the story of Josephine Caldwell and Isaiah Turner fades once more into the shadows of history, remembered only in whispers and warnings, in the reluctance of locals to linger in a certain park after dark, and in the sound of chains that some still claim to hear when the winter wind blows through the town of Milfield, Virginia.

For those who study the darker aspects of human nature, the case serves as a reminder that the most terrifying monsters are not supernatural creatures, but ordinary people whose minds have turned inward, transforming natural emotions into something unrecognizable and deadly.

And perhaps most disturbing of all is the knowledge that such capacity exists within us all.

the potential to forge chains of obsession that bind not only those we claim to love but ourselves as well.

As winter descends once more upon the Shenandoa Valley, and snow begins to fall on the small park that once housed the Caldwell Merkantile, one cannot help but wonder, do they remain there still, locked in their eternal struggle? And if so, has a century and a half of shared captivity brought them any closer to understanding the true nature of the chains that bind them? Some questions perhaps are better left unanswered, some chains better left unbroken.

News

✈️ U.S. F-15 FIRST STRIKE — ALLEGED CARTEL DRUG LAB ERASED IN SECONDS AS SKY ERUPTS IN A BLINDING FLASH ✈️ What officials described as a precision operation turned the night into daylight, with jets screaming overhead and a suspected production site reduced to smoking rubble in moments, sending a shockwave across the region and a message that the airspace above is no safe haven for hidden empires 👇

The Last Fortress: A Shocking Revelation In the heart of the Mexican jungle, Diego stood at the entrance of the…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: FBI & ICE SHATTER ALLEGED TRUCKING NETWORK WITH SOMALI TIES — 83 ARRESTED, $85M IN CASH AND WEAPONS STACKED AS EVIDENCE 🚨 Before sunrise, federal agents swept through depots and dispatch offices, hauling out duffel bags of currency and seizing firearms while stunned neighbors watched a logistics operation authorities claim was hiding a sprawling criminal enterprise behind everyday freight routes 👇

The Shadows of the Ghost Fleet In the heart of the Midwest, where the snow fell like a blanket over…

🚨 FBI & ICE STORM GEORGIA “CARTEL HIDEOUT” — GRENADE LAUNCHER DISCOVERED AND $900K IN DRUGS SEIZED IN A DAWN RAID THAT SHOCKED THE BLOCK 🚨 What neighbors thought was just another quiet morning exploded into flashing lights and tactical vests as agents swept the property, hauling out weapons and evidence while officials described a months-long investigation that culminated in a swift, coordinated takedown 👇

The Unraveling of Shadows: A Tale of Betrayal and Redemption In the heart of Jackson County, Georgia, the air was…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: DEA & FBI CRUSH ALLEGED CARTEL TRUCKING EMPIRE — HIDDEN ROUTES MAPPED, DRIVERS DETAINED, AND MILLIONS STACKED AS EVIDENCE 🚨 Before sunrise, highways turned into a grid of flashing lights as agents intercepted rigs, cracked open trailers, and traced coded dispatch logs, revealing what officials describe as a logistics web hiding in plain sight behind ordinary freight lanes 👇

The Fall of Shadows: A Cartel’s Empire Exposed In the dimly lit corridors of power, where shadows danced with deceit,…

🚢 U.S. NAVY TRAPS SINALOA CARTEL’S ALLEGED $473 MILLION “DRUG ARMADA” AT SEA — AND THE HIGH-STAKES STANDOFF UNFOLDS UNDER FLOODLIGHTS AND ROTOR WASH 🚢 Radar screens lit up, cutters boxed in fast boats, and boarding teams moved with clockwork precision as authorities described a sweeping maritime interdiction that turned open water into a chessboard, stacking seized cargo on deck while prosecutors hinted the ripples would travel far beyond the horizon 👇

The Abyss of Deceit: A Naval Reckoning In the heart of the Caribbean, where the turquoise waters glimmered under the…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: DEA & FBI DESCEND ON MASSIVE TEXAS LOGISTICS HUB — 52 TONS OF METH SEIZED AS 20 POLITICIANS ALLEGEDLY TIED TO A SHADOW NETWORK ARE THRUST INTO THE SPOTLIGHT 🚨 What began as a quiet federal probe detonated into a sweeping raid of warehouses and boardrooms, with agents hauling out towering stacks of evidence while stunned insiders whisper that the real shockwave isn’t just the drugs — it’s the powerful names now facing intense scrutiny 👇

Shadows of the Underground: The Texas Cartel Unveiled In the heart of Texas, where the sun sets over sprawling landscapes,…

End of content

No more pages to load