The Alabama Bride Who Vanished After Freeing Her Husband’s Slave (1842)

Welcome to this journey through one of the most disturbing cases recorded in the history of Alabama.

Before we begin, I invite you to leave in the comments where you’re watching from and the exact time you’re listening to this narration.

We are interested to know which places and at what times of day or night these documented stories reach.

The year was 1842 when Katherine Williams first arrived in Montgomery County, Alabama.

The carriage wheels cut through the red clay roads, leaving behind Boston’s cobblestones and her family’s disapproving glances.

The autumn air carried the scent of cotton fields stretching for miles under the merciless southern sun.

Workers bent at unnatural angles, their backs permanently curved from years of harvest.

Catherine noticed how they never looked up as the carriage passed.

Not once.

Her new home stood at the end of a long oakline driveway, Magnolia Ridge Plantation, a name that would later be whispered with unease by locals for decades to come.

The white columns of the main house reached toward the sky like pale fingers, supporting a facade of southern prosperity built on invisible foundations that creaked with secrets.

The neighboring plantations, Willow Creek to the east and Thornfield 3 mi south, formed a triangle of wealth and privilege in Montgomery County.

Theodore Williams waited on the porch steps.

At 39 years old, he was 18 years Catherine senior, but their arrangement had been sealed through letters and family negotiations long before they ever met in person.

a marriage of convenience connecting northern textile money to southern land.

What no one predicted was that Katherine Williams would disappear exactly 73 days after arriving at Magnolia Ridge, and that her disappearance would coincide with the escape of Theodore’s most valued house servant, a fact that many found too convenient to be coincidental.

According to the plantation ledger, still preserved in the Alabama State Archives, Theodore Williams owned 47 people at the time of Catherine’s arrival.

Most worked the fields, but one, a man called Solomon, worked exclusively inside the main house.

What made Solomon’s position unusual was that he had been gifted to Theodore by Catherine’s father as part of her dowy.

A human being transferred from one owner to another alongside silver and linens.

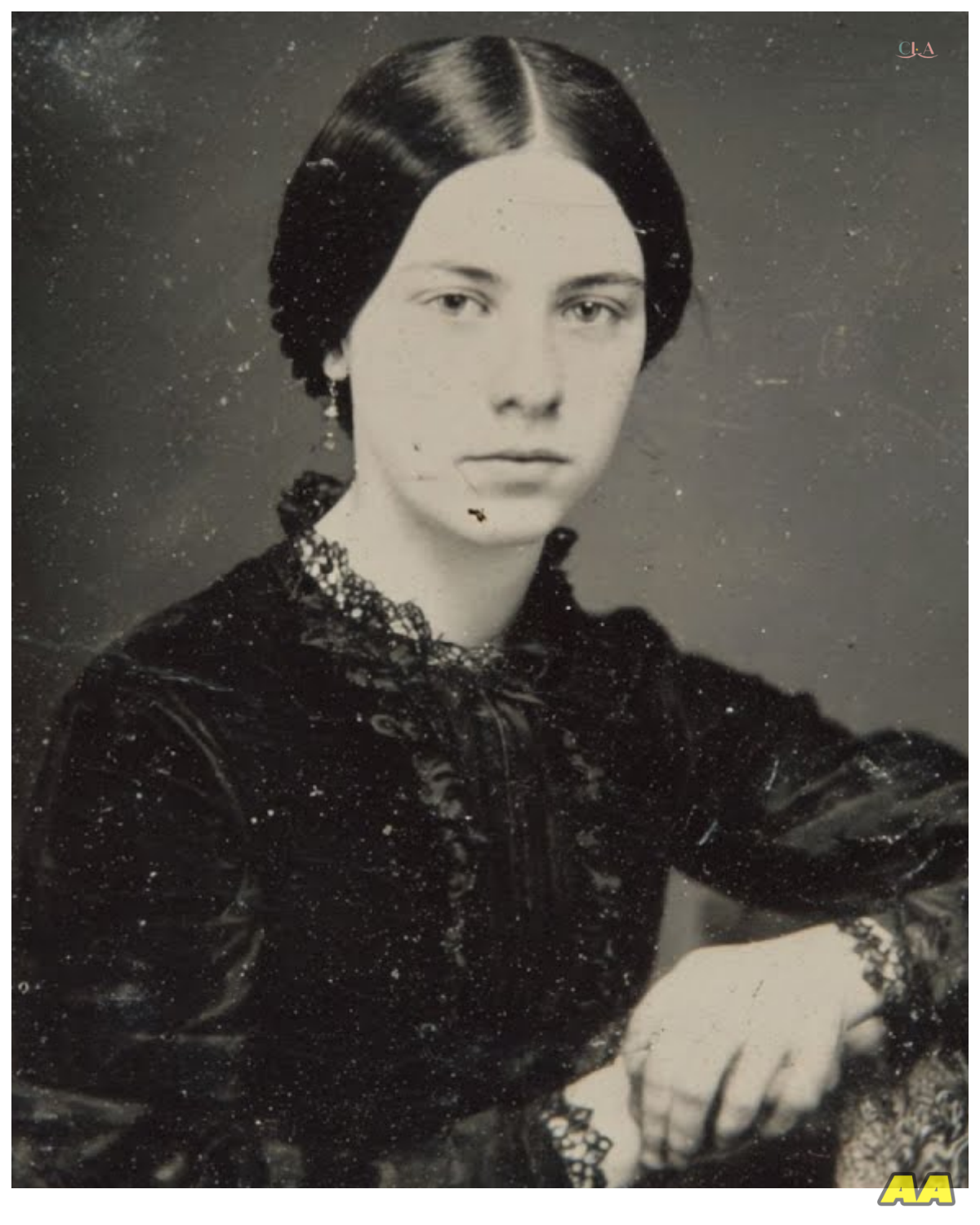

Records from that time describe Catherine as a woman of unusual education and quiet disposition.

According to the few letters she wrote home during her brief time at Magnolia Ridge, the local postmaster later testified that she rarely ventured into town, appearing only twice at the general store and once at the Montgomery Presbyterian Church before her disappearance.

What happened during those 73 days behind the white columns of Magnolia Ridge has been pieced together from fragments, servant testimonies, Theodore’s statements, neighboring accounts, and a partial diary found 26 years later during renovations to the East Wing.

The first unusual incident occurred approximately 3 weeks after Catherine’s arrival.

Martha Jenkins, the wife of the neighboring Thornfield plantation owner, reported visiting Catherine for afternoon tea.

She described finding the new bride sitting motionless in the parlor, staring at a closed door leading to Theodore’s study.

When addressed, Catherine allegedly did not respond for several moments, then turned with a smile that never reached her eyes.

According to Mrs.

Jenkins account preserved in a letter to her sister in Richmond.

Catherine spoke of hearing conversations through the walls at night, discussions between her husband and someone whose voice sounded like it came from the bottom of a well.

Theodore’s business ledgers show that in the weeks following Catherine’s arrival, he began making unusual purchases.

hardware supplies, locks, hinges, and lumber in quantities suggesting significant construction, though no additions to the house were recorded.

The receipts filed in the county courthouse as part of later investigations, show deliveries being made after sundown, which local merchants found peculiar enough to note in their records.

On October 12th, 1842, Theodore hosted a dinner for neighboring plantation owners, an event documented in multiple sources.

During this gathering, several guests noted Catherine’s absence until midway through the meal when she appeared wearing what Mrs.

Jenkins described as a dress more suited to mourning than hosting.

According to the account of James Harrison, owner of Willow Creek Plantation, Katherine spoke little, but at one point interrupted a discussion about property boundaries by asking, “How deep must one dig before the land truly belongs to them.

” The question was met with uncomfortable laughter and quickly dismissed.

The following day, Theodore’s personal physician, Dr.

Robert Anderson, was summoned to Magnolia Ridge.

His ledger, discovered in 1967 in his grandson’s attic, records treating Catherine for feminine hysteria and delusions, prescribing bed rest and isolation.

The same ledger contains a curious marginal note.

Patient insists on sounds beneath floorboards.

Husband confirms recent rodent issues.

Peculiar scratching observed during examination.

Catherine’s daily movements became increasingly restricted following this medical visit.

Household staff later testified that Theodore insisted his wife was of fragile northern constitution unsuited to Alabama heat.

He ordered windows in the east wing sealed and instructed that no one should disturb her rest.

Sarah Johnson, a kitchen worker, reported that meals sent to Catherine’s room often returned untouched, though the water pitcher was consistently emptied.

The night of November 4th brought a severe storm to Montgomery County.

Lightning struck a tree on Magnolia Ridge property, causing a fire in one of the outbuildings.

During the confusion of containing the blaze, several workers reported seeing Catherine standing in the rain, staring not at the fire, but toward the treeine at the property’s edge.

Theodore quickly ushered her inside, but not before she was heard asking one of the field hands about the paths beyond the North Creek.

This worker, whose name was recorded only as Eli in subsequent investigations, would later disappear himself, with some suggesting he had been sold to a plantation further south to prevent further questioning.

In mid- November, Catherine convinced Theodore to allow her a trip into Montgomery proper, accompanied by Solomon.

According to the account of shopkeeper William Parker, preserved in county records, Catherine purchased writing paper, ink, and a small locked box.

Parker noted that she spoke quietly to Solomon during the transaction in a manner he found uncommonly familiar.

More significantly, Catherine visited the offices of Harold Thompson, one of the few attorneys in Montgomery County at that time, while Solomon waited outside with the carriage.

The content of their meeting remains unknown as Thompson maintained client confidentiality even during later investigations.

His only recorded statement on the matter was that Mrs.

Williams inquired about certain legal matters related to property transfer.

The night of November 23rd, 1842 brought unusually cold weather to Alabama.

Theodore Williams later reported going to bed with Catherine around 9:00, only to wake at midnight and find her side of the bed empty.

According to his formal statement to the sheriff, he assumed she had gone to the washroom and returned to sleep.

It wasn’t until morning that her absence was noted, and a search of the property initiated.

What makes this case particularly disturbing was the discovery that Solomon had also vanished that same night.

Theodore immediately concluded that Catherine had been abducted, possibly harmed.

He organized search parties that combed the surrounding woods and swampland for 3 days.

No trace of either Catherine or Solomon was found.

The sheriff’s report filed on November 27th notes that no signs of struggle were evident in Mrs.

Williams chambers, though the bed showed signs of having been slept in.

A single candlestick was missing from the mantle, suggesting she departed of her own accord in darkness.

The official investigation took a turn when Sarah Johnson, the kitchen worker, revealed that she had observed Catherine and Solomon in what she described as private conversations on at least three occasions in the weeks before the disappearance.

According to her testimony preserved in county records, Catherine had been seen passing something to Solomon, possibly papers, during one such exchange.

Sarah was dismissed from service at Magnolia Ridge the day after providing this information to authorities.

Her subsequent whereabouts remain unknown.

Theodore Williams offered a substantial reward for information leading to Catherine’s return or Solomon’s capture, $500 for his wife, $1,000 for the servant.

The disparity in these amounts was noted by some northern newspapers that picked up the story, though southern publications focused exclusively on the theft of valuable property and the tragic abandonment of a gentleman by his new bride.

The investigation stalled by December with most local authorities concluding that Catherine had either fallen victim to an accident in the woods or had willingly fled north with Solomon.

Theodore appeared to accept the latter theory, filing for an enulment on grounds of abandonment in January of 1843.

The document preserved in county records makes no mention of Catherine’s potential whereabouts, but includes a detailed description of Solomon for identification purposes should he be captured in another state.

Life at Magnolia Ridge returned to its rhythms.

Theodore withdrew from social engagements for a period considered appropriate for mourning, then resumed his position among Montgomery Countyy’s elite.

By all accounts, he never remarried.

His business ledgers show that he acquired additional workers in the spring of 1843, expanding cotton production significantly.

The east wing of the house, where Katherine had spent most of her time, was closed off.

its windows boarded from the inside for reasons Theodore never explained to visitors.

The case might have remained nothing more than a footnote in county history had it not been for the events of 1868, 26 years after Catherine’s disappearance.

During reconstruction, Magnolia Ridge Plantation was seized and the main house repurposed as a temporary administrative office for Union forces.

During renovations to the east wing, workers removed floorboards in what had been Catherine’s sitting room and discovered a small space between the floor and foundation.

Not unusual in houses of that era for ventilation purposes.

What was unusual was the discovery of a small wooden box sealed with wax and containing three items.

a leatherbound diary with Catherine’s initials, a folded document bearing the seal of attorney Harold Thompson, and a brooch containing a dgera type of a woman presumed to be Catherine’s mother.

The diary was partially damaged by moisture, with many pages illeible, but several entries remained intact enough to read.

The contents were troubling enough that Captain Marcus Reynolds, the Union officer overseeing the renovation, forwarded the materials to federal authorities rather than local officials.

The legible diary entries, transcribed and preserved in the National Archives paint a disturbing picture of Catherine’s brief time at Magnolia Ridge.

An entry dated October 3rd reads, “I have heard it again tonight.

Not rats or house settling as tea insists.

The sound is distinctly human, a low humming punctuated by what can only be described as weeping.

It comes from beneath, not beside or above.

Tea becomes agitated when I mention it.

Tonight I noticed scratches on Solomon’s wrists.

He would not meet my eyes when serving dinner.

An entry from October 19th states, “The believes I am resting, but I have discovered the purpose of his late night construction.

There is a space beneath the east wing, not a proper cellar, but a crawl space accessible through a trap door concealed beneath the carpet in his study.

I observed him from the window as he descended last night, carrying food and water.

He remained below for 23 minutes.

” Solomon knows I have seen recognition in his eyes when the sounds begin.

The most disturbing entry dated November 1st reads, “God forgive me for my family’s participation in this institution.

What I have learned cannot be unlearned.

What I have seen cannot be unseen.

The person beneath the floor is Thomas, Solomon’s brother, purchased by my father and gifted to tea as part of our arrangement.

Kept alive but hidden.

a leverage to ensure Solomon’s compliance and exceptional service.

Te explained it as casually as one might discuss the training of a hunting dog.

I cannot remain in this house.

I have written to Mr.

Thompson regarding certain legal matters.

Solomon has agreed to help if I can secure proper papers.

The legal document found alongside the diary appears to be a manu mission paper drawn up by attorney Thompson granting freedom to Solomon.

How Catherine obtained Theodore’s signature remains a mystery, though one theory suggests she may have presented it among plantation business papers requiring his attention.

The document bears a proper signature and seal, making it legally binding even in Antibbellum, Alabama, though limited in practical protection once beyond state lines.

What happened to Catherine and Solomon after they fled Magnolia Ridge unknown.

No confirmed sightings were ever documented.

Theodore maintained until his death in 1874 that Catherine had been coerced or manipulated by Solomon, refusing to consider any alternative narrative.

The discovery of the diary and documents came too late for any meaningful justice.

The war had ended, slavery had been abolished, and Theodore had lost much of his fortune in the Confederate collapse.

Local legend in Montgomery County claims that Theodore never actually closed off the east wing due to grief as he had claimed.

Some suggest he sealed it because he could still hear the sounds from below.

The brother who may have remained trapped in the crawl space, forgotten in the chaos of Catherine’s disappearance.

This theory gained traction after an archaeological survey in 1952 discovered human remains beneath the former east-wing foundations.

Remains that were never properly identified before the site was developed into farmland.

One intriguing possibility emerged in 1896 when a women’s suffrage newsletter in Massachusetts published an obituary for a Catherine Solomon, formerly of Boston, who dedicated her later years to abolitionist causes.

The brief notice mentioned that she had returned from southern states with firsthand knowledge of plantation cruelties and had assisted many in their journey to freedom.

Whether this Catherine Solomon was formerly Katherine Williams of Magnolia Ridge cannot be confirmed.

As for Katherine Williams, no death certificate or subsequent marriage record has ever been located under her name.

The diary, manu mission paper, and brooch were transferred to the National Archives in 1964, where they remain available for scholarly review.

The remains of Magnolia Ridge Plantation have largely disappeared, absorbed by commercial development outside Montgomery.

No historical marker identifies the location.

The neighboring Thornfield and Willow Creek plantations similarly vanished from the landscape, though their names occasionally appear in local real estate designations.

Ghostly echoes of a history that Alabama has struggled to reconcile.

For those who study disappearances of this era, Katherine Williams represents a particular category.

Those who vanish not due to violence but by choice, rejecting the society they were born into.

Solomon’s fate remains equally ambiguous.

Did they reach the north? Did they separate after escaping Alabama? The historical record falls silent, leaving us with questions that echo like footsteps in an empty house.

And perhaps that silence is appropriate.

In a time when humans were considered property, when women had few legal rights, the greatest act of rebellion was simply to disappear, to remove oneself from the narrative others had written.

Katherine Williams stepped off the pages of recorded history on November 23rd, 1842.

Whether she wrote her own story afterward, we may never know.

Researchers at the University of Alabama proposed a ground penetrating radar survey of the former Magnolia Ridge property in 1968, seeking to determine if other remains might be found beneath the foundation of the longgone house.

The proposal was denied by the property’s then owners, and the opportunity was lost when the site was cleared for construction the following year.

Some questions about Magnolia Ridge will remain forever buried, much like whatever or whoever may have once been kept beneath its floors.

The box containing Catherine’s diary and the other artifacts was briefly misplaced during a reorganization of the National Archives in the early 1960s.

For nearly a year, the items were considered lost before being rediscovered misfiled among Civil War hospital records.

During this period, rumors circulated that the box had been deliberately hidden or destroyed due to the troubling nature of its contents.

Such conspiracy theories persist in certain historical circles, though no evidence supports claims of intentional suppression.

Those who have examined the diary pages note a distinct change in Catherine’s handwriting as the entries progress.

The neat, educated script of early October gives way to increasingly hurried, slanted writing by November, suggesting deteriorating mental state or growing urgency.

The final entry dated November 22nd, one day before her disappearance, consists of just five words.

Tomorrow, Northstar, God willing.

And so the story of Katherine Williams and Solomon fades into the shadows of American history.

A brief, disturbing chapter in the long narrative of a nation built on contradictions.

Her 73 days at Magnolia Ridge left barely a trace in official records.

Yet the ripples of her choices may have extended far beyond what documents can tell us.

Sometimes the most important stories are those that remain half-told, existing in the spaces between established facts.

The land where Magnolia Ridge once stood is now part of a commercial development outside Montgomery.

People shop, dine, and work there every day, unaware they walk above ground that may still hold secrets.

Traffic passes over the red clay that once felt the weight of Catherine’s carriage as she arrived full of trepidation on that autumn day in 1842.

The Magnolia are gone.

The Oakline Drive is now a four-lane road.

But somewhere perhaps the diary of what really happened during those 73 days exists intact.

Its pages filled with a truth too disturbing for its time.

For now we are left with fragments and whispers.

A bride who vanished.

A man who escaped bondage, a space beneath the floorboards, and the lingering question in fleeing from monsters.

Did Katherine Williams find freedom, or did she simply disappear into the vast silence that has swallowed so many others? Some stories don’t end, they simply stop being told.

In 1956, an elderly woman named Elellanar Blackwood contacted the Alabama Historical Society with a curious claim.

According to documented correspondence still held in their archives, Miss Blackwood stated that her grandmother had been a household servant at Willow Creek Plantation during the time of Katherine Williams disappearance.

The letter described how her grandmother had mentioned seeing Catherine in the company of Solomon near the North Creek just before dawn on the morning of November 23rd, not fleeing in panic, but walking purposefully, carrying a small bundle.

Elellanena Blackwood’s account included one detail never published in any newspaper or official report.

Catherine Williams was allegedly wearing men’s attire, her hair concealed beneath a cap.

This detail might seem insignificant, but it suggests premeditation rather than impulsive flight.

More tellingly, it indicates that someone within the household had assisted with these preparations.

Historical society officials interviewed Miss Blackwood, but without corroborating evidence, her grandmother’s story was filed away as unverifiable hearsay.

The interviewer’s notes, however, include a curious addendum.

Subject appears sincere and of sound mind.

Claims grandmother mentioned a network of helpers stretching from Montgomery to Cincinnati.

The reference to Cincinnati is particularly intriguing given what we now know about the Underground Railroads operations during this period.

While most documented routes ran through eastern states, several historians have identified lesserk known western paths through Alabama, Mississippi, and Tennessee.

These routes were especially perilous with fewer safe houses and greater distances between them.

If Catherine and Solomon attempted this journey, they faced not only the immediate danger of pursuit, but the harsh winter conditions of 1842, documented as unusually severe throughout the South.

A survey of church records from Cincinnati, conducted in 1962, revealed an intriguing possibility.

The First Presbyterian Church’s charity registry for April 1843, approximately 5 months after Katherine’s disappearance, lists assistance provided to CW and Companion, recently arrived from Southern Territories in need of winter clothing and temporary lodging.

The entry notes that the recipients were directed to a boarding house operated by known abolitionist Martha Simmons.

Unfortunately, Simmons records were destroyed in a fire in 1847, eliminating any possibility of confirmation.

The timing aligns with the estimated journey duration for travelers moving north by foot and occasional clandestine transport.

Winter conditions would have slowed their progress considerably, forcing longer stays at safe houses and more securitous routes to avoid detection.

If CW was indeed Katherine Williams, she had successfully traversed approximately 700 m through hostile territory, an extraordinary feat for a woman described in contemporary accounts as delicate and unused to physical hardship.

In 1861, as the Civil War began, a small abolitionist newspaper in Boston published a series of anonymous accounts from individuals who had escaped or facilitated escapes from southern plantations.

One such account, published on May 19th, described a plantation mistress who chose conscience over comfort and joined a former house servant in flight northward.

While no names were mentioned, certain details align remarkably with what we know of Catherine and Solomon.

The author described discovering an unspeakable arrangement beneath the house and mentioned traveling through seven weeks of winter wilderness before reaching safety.

Most significantly, the account referenced carrying legal papers that meant nothing in practice, but everything in principle, possibly alluding to the manumission document found in Catherine’s hidden box.

The newspaper’s records indicate that the account was submitted by mail from an undisclosed location in Western New York.

The editor’s notes mentioned that the writer requested anonymity due to ongoing concerns for safety and the welfare of others still engaged in the cause.

Given the political climate of 1861, with war declared and tensions at their peak, such caution would have been entirely warranted.

If Catherine was indeed the author, she had survived at least 19 years after her disappearance from Magnolia Ridge.

Theodore Williams response to Catherine’s disappearance evolved over time according to accounts from neighbors and business associates.

James Harrison of Willow Creek Plantation noted in his personal correspondence preserved by his descendants and donated to the Alabama archives in 1949 that Theodore initially appeared genuinely distressed, organizing search parties and offering rewards.

However, by January of 1843, his demeanor had changed marketkedly.

Harrison described him as possessed of a cold fury and dedicated to business affairs with unusual intensity.

The ledgers show that Theodore doubled his plantation’s output over the next 3 years, acquiring additional land and workers at a pace that raised eyebrows even among his fellow planters.

More telling is Theodore’s reaction to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

County records show that he personally financed three recovery expeditions to northern states, ostensibly searching for Solomon.

These expeditions, led by professional slave catchers, focused particularly on communities in Ohio and New York with known abolitionist sympathies.

None were successful in locating Solomon, but according to expense accounts filed with Theodore’s estate papers, the search continued sporadically until 1859, 17 years after the disappearance.

Theodore never publicly mentioned Catherine in these later recovery efforts.

His correspondence with recovery agents, partially preserved in his business records, references only property removal and outstanding debts.

Whether his persistence stemmed from genuine loss, wounded pride, or fear of what Catherine might reveal about Magnolia Ridge remains a matter of speculation.

What is clear is that Theodore Williams never relinquished his sense of ownership, even as the nation moved incrementally toward a different understanding of human liberty.

The east wing of Magnolia Ridge Plantation remained sealed until the Union Army’s requisition of the property in 1868.

According to the testimony of Isaiah Turner, a former worker who provided information to Union Captain Marcus Reynolds, Theodore maintained the curious habit of standing outside those boarded windows on certain evenings, particularly during November.

Turner described seeing Theodore place his palm flat against the sealed window frame as though feeling for warmth or movement within.

When questioned directly about the east wing, Theodore reportedly told visitors it remained closed due to persistent structural concerns rather than sentimental attachment.

The human remains discovered beneath the east-wing foundations during the 1952 survey present one of the case’s most disturbing elements.

The survey report completed by archaeologist Dr.

William Foster describes finding adult male remains in a space approximately 3 ft high and 6 ft square, accessible only through a narrow trap door that had been subsequently sealed from above.

The report notes that the condition of the remains made precise dating difficult, but they were consistent with the antibbellum period.

Most significantly, the bones showed evidence of prolonged confinement, including pressure abrasions consistent with shackles or restraints.

Dr.

Foster’s request for more thorough examination was denied by county officials, who ordered the remains reeried without further investigation.

His field notes preserved at the University of Alabama include the observation that the space contained sufficient room for a human to survive for extended periods if provided minimal sustenance and that scratch marks on the wooden supports suggest desperate attempts to either signal or escape.

These findings lend credibility to Catherine’s diary entries about the person beneath the floor identified as Thomas Solomon’s brother.

The practice of separating enslaved family members as a control mechanism was well documented throughout the antibbellum south.

However, the extreme measure of keeping one brother effectively buried alive to ensure another’s compliance suggests a level of psychological manipulation beyond even the brutal standards of the time.

If Catherine’s diary is accurate, Theodore Williams had refined cruelty to an art form, creating a living hostage situation that guaranteed Solomon’s exceptional service and prevented escape attempts until Catherine’s arrival changed the equation.

What remains unclear is Thomas’s fate after Catherine and Solomon’s departure.

If he was indeed still confined beneath the house, did Theodore release him, transfer him to fieldwork? The sales records show no new acquisitions that might have replaced Solomon’s household position in the weeks following the disappearance.

One disturbing possibility suggested by the condition and location of the remains is that Thomas was simply abandoned in his underground prison, either as punishment for his brother’s escape or because Theodore feared what Thomas might reveal if released.

The silence of historical records on this point speaks volumes about whose lives were considered worth documenting.

Thomas exists in official history only as a nameless set of remains discovered a century later.

His suffering both during confinement and potentially afterward went unrecorded by those who maintained meticulous accounts of cotton yields and property values.

In this context, Catherine’s diary takes on additional significance as perhaps the only document that acknowledged his existence as a person rather than property.

During reconstruction, Magnolia Ridge Plantation was eventually divided and sold to several smaller farmers, including some formerly enslaved families.

The main house gradually deteriorated with locals describing it as haunted or sickly ground.

By 1890, the structure had been dismantled for building materials, leaving only the foundation and chimney stones.

These two disappeared as development encroached throughout the 20th century.

Today, the exact location of the east wing can only be approximated through land surveys and historical maps.

The story of Katherine Williams might have remained buried in county archives had it not been for the civil rights movement of the 1960s, which prompted renewed interest in untold stories of resistance to slavery.

Historian Dr.

Margaret Coleman stumbled upon references to the case while researching women’s involvement in abolitionist activities.

Her 1967 paper, The Disappeared Mistress, Katherine Williams, and the Politics of Memory, brought academic attention to the fragmentaryary evidence surrounding the case.

Dr.

Coleman’s research uncovered an additional piece of the puzzle in Theodore Williams’s obituary published in the Montgomery Advertiser in 1874.

The brief notice mentioned that he died without family, his wife having preceded him in death some 30 years prior.

This phrasing preceded him in death rather than disappeared suggests Theodore had eventually accepted or assumed Catherine’s death.

More intriguing is the obituary’s reference to his peculiar habit of keeping a locked room in his house which he alone entered on the anniversary of some private sorrow.

If this room was within the sealed east wing, it suggests Theodore maintained some ritual connection to the events of 1842 until his death.

The case took another turn in 1969 when researchers at Oberlin College in Ohio, a known terminus of the Underground Railroad, discovered a list of donations to the college’s scholarship fund from 1852.

Among the contributors was a Mrs.

C.

Solomon who provided a modest but significant sum earmarked for education of those formerly in bondage.

The address provided was in Rochester, New York, a city known for its strong abolitionist community and the home of Frederick Douglas’s newspaper, The North Star.

The name Solomon takes on particular significance in light of Catherine’s diary reference to Solomon’s brother Thomas.

If Catherine took Solomon’s name after their escape, either as disguise or out of genuine relationship, it would explain that Catherine Solomon referenced in the Massachusetts suffrage newsletter abituary discovered earlier.

It would also align with practices documented among some abolitionists who sometimes formed family-like bonds with those they helped escape.

The historical record offers no definitive evidence of the exact nature of Catherine and Solomon’s relationship after their flight, but their names remain linked across multiple archival sources spanning several decades.

Rochester City directories from 1853 through 1860 list a C.

Solomon seamstress at an address near the city’s third ward, an area known for its abolitionist activity.

The 1860 census records for that address show a household headed by Katherine Solomon, age 45, birthplace Massachusetts, living with Samuel Solomon, age 50, birthplace undisclosed.

Whether Samuel was Solomon’s chosen free name remains speculation, but the ages and origins align with what we know of Catherine Williams and the man who escaped with her.

The most tantalizing potential evidence emerged in 1972 when a family in Rochester donated a collection of letters to the city’s historical society.

Among them was correspondence between their ancestor, a known underground railroad conductor, and various contacts along the network.

One letter dated June 1843 makes reference to the unusual pair recently arrived from Deepest Alabama, the lady and her companion who reversed the expected roles.

The letter goes on to state that they carry papers of significant moral, if not legal weight, and their account of conditions at their former residence has strengthened the resolve of many previously hesitant supporters.

If this refers to Catherine and Solomon, it suggests they had integrated into abolitionist circles in Rochester by mid 1843 and were sharing their experiences to further the cause.

The papers of significant moral weight likely refers to the manum mission document Catherine had secured for Solomon, a powerful symbol, even if uninforcable in practice once they returned to the south.

The reference to reversed roles almost certainly alludes to a white plantation mistress choosing to flee with an enslaved person, an extraordinary reversal of the social order that would have made their story particularly compelling to abolitionist audiences.

The Rochester Historical Society records include fragmentaryary references to public talks given by unnamed escaped slaves and their allies throughout the 1840s and 50s.

One such event advertised in the Rochester Freeman in October 1847 promised testimony from one who witnessed the peculiar institution from both sides of the divide.

While no transcripts of these talks survive, they demonstrate that firsthand accounts from the South were actively sought and shared within northern abolitionist communities.

The Civil War brought significant changes to Rochester’s abolitionist community as many redirected their energies toward supporting the Union cause.

City records show that Samuel Solomon enlisted in the US colored troops in 1863 despite being approximately 53 years old at the time, well above typical enlistment age.

His military record lists his previous occupation as carpenter and notes that he served primarily in non-combat support roles until the war’s end.

He returned to Rochester in 1865 where city directories show he established a small carpentry business.

Katherine Solomon’s activities during the war years are less documented.

The Rochester Ladies Anti-Slavery Society records mention a MS s who coordinated bandagemaking efforts and collected supplies for colored regiments.

Whether this was Catherine remains unconfirmed.

By 1870, the Rochester directory shows widow C.

Solomon at the same address, suggesting that Samuel, like Solomon, had died by this time.

The widow designation is particularly interesting, as it implies a legally recognized marriage, something that would have been impossible during their time in Alabama.

The Massachusetts Suffrage News Letter obituary from 1896 describes Katherine Solomon as having dedicated her remaining years to causes of justice, particularly education for freed men and political rights for women.

It mentions that she left no children but many who considered her a mother figure in the struggle for liberty.

According to the notice, she was buried in Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester, the same cemetery where Frederick Douglas was laid to rest.

However, cemetery records from this period are incomplete, and no marked grave bearing her name has been identified.

If the Catherine Solomon who died in Rochester in 1896 was indeed formerly Katherine Williams of Magnolia Ridge Plantation, she lived 54 years after her dramatic escape from Alabama.

During those decades, she would have witnessed the Civil War, emancipation, reconstruction, and its subsequent unraveling.

The world she left behind in 1842 transformed radically, though never completely.

The questions she faced that November night about courage, complicity, and the price of silence remain relevant to American society today.

The story of Katherine Williams and Solomon represents a rarely documented narrative in American history.

One where those with privilege chose to reject it out of moral conviction.

That their story survives only in fragments speaks to the power of the systems they challenged.

Records were not designed to preserve accounts of resistance, but to maintain the status quo.

Every diary entry, newspaper mention, and census record that helps reconstruct their journey exists almost by accident.

Small tears in a carefully woven fabric of historical amnesia.

For researchers and historians, the case raises methodological questions about how we reconstruct lives that deliberately stepped outside official documentation.

Catherine and Solomon’s story emerges not from a single authoritative source, but from the convergence of multiple fragmentaryary records, none of which tells the complete story alone.

Like the locked box hidden beneath Magnolia Ridg’s floorboards, their truth remained concealed until time and circumstance revealed it partially to the world.

Perhaps most haunting is what remains unknown.

Did Thomas survive his underground confinement? Did Katherine and Solomon remain together throughout their lives in freedom? Did they maintain contact with the networks that helped them escape? Did they ever fear recapture even decades later? The historical record offers tantalizing suggestions, but no definitive answers.

Their story, like so many from this period, remains suspended between documented fact and necessary speculation.

The commercial development that now stands where Magnolia Ridge once dominated the landscape contains nothing to commemorate what transpired there.

Shoppers pushing carts across the parking lot walk unknowingly above ground that once held a house divided quite literally between the visible performance of southern gentility and the hidden brutality that sustained it.

The red clay that once absorbed the sounds from beneath the floorboards now supports concrete foundations and asphalt.

Its secrets sealed beneath progress and convenience.

In 21st century Alabama, where debates about historical memory and commemoration continue, the story of Katherine Williams occupies an ambiguous position.

She was neither victim nor heroine in the traditional sense, neither entirely of the north nor the south.

Her 73 days at Magnolia Ridge represent a brief moment when the carefully maintained boundaries between owner and owned, husband and wife, north and south, became suddenly permeable.

When a single decision to listen rather than ignore, set in motion consequences that would echo across decades.

Today, the box containing Catherine’s diary remains in the National Archives, accessible to researchers, but largely unknown to the general public.

The Dgera type inside the brooch shows a stern-faced woman in her 50s, presumably Catherine’s mother, who could not have imagined her daughter’s fate when she posed for the image.

The manumission paper with Theodore’s hasty signature represents both a legal fiction and a profound truth that freedom once conceived cannot easily be contained.

For those who study this period of American history, Katherine and Solomon’s journey offers a rare window into the complex moral geography of the antibbellum south.

a landscape where physical escape required traversing not just hundreds of miles of hostile territory, but crossing boundaries of identity and allegiance that few were willing to breach.

Their story reminds us that even within systems designed to eliminate moral agency, individuals sometimes found ways to reclaim it, often at tremendous personal cost.

As for Magnolia Ridge itself, nothing remains but fragments scattered across archives and memories fading with each generation.

The white columns, the Oakline Drive, the secret trap door, all have vanished from the physical world.

Yet in documents and testimonies, in census records and newspapers, in the human remains found beneath concrete foundations, echoes of those 73 autumn days in 1842 continue to resonate, a reminder that history’s darkest chapters often contain unexpected moments of courage and terrible acts of cruelty.

sometimes within the same household, sometimes within the same heart.

The sound that Catherine heard beneath the floorboards has long since fallen silent.

But for those willing to listen closely to the historical record, with all its gaps and inconsistencies, other sounds emerge.

carriage wheels on red clay roads, whispered conversations between unlikely allies, footsteps in pre-dawn darkness heading toward the North Creek, and the quiet turning of a key in a lock that was never meant to be opened.

News

✈️ U.S. F-15 FIRST STRIKE — ALLEGED CARTEL DRUG LAB ERASED IN SECONDS AS SKY ERUPTS IN A BLINDING FLASH ✈️ What officials described as a precision operation turned the night into daylight, with jets screaming overhead and a suspected production site reduced to smoking rubble in moments, sending a shockwave across the region and a message that the airspace above is no safe haven for hidden empires 👇

The Last Fortress: A Shocking Revelation In the heart of the Mexican jungle, Diego stood at the entrance of the…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: FBI & ICE SHATTER ALLEGED TRUCKING NETWORK WITH SOMALI TIES — 83 ARRESTED, $85M IN CASH AND WEAPONS STACKED AS EVIDENCE 🚨 Before sunrise, federal agents swept through depots and dispatch offices, hauling out duffel bags of currency and seizing firearms while stunned neighbors watched a logistics operation authorities claim was hiding a sprawling criminal enterprise behind everyday freight routes 👇

The Shadows of the Ghost Fleet In the heart of the Midwest, where the snow fell like a blanket over…

🚨 FBI & ICE STORM GEORGIA “CARTEL HIDEOUT” — GRENADE LAUNCHER DISCOVERED AND $900K IN DRUGS SEIZED IN A DAWN RAID THAT SHOCKED THE BLOCK 🚨 What neighbors thought was just another quiet morning exploded into flashing lights and tactical vests as agents swept the property, hauling out weapons and evidence while officials described a months-long investigation that culminated in a swift, coordinated takedown 👇

The Unraveling of Shadows: A Tale of Betrayal and Redemption In the heart of Jackson County, Georgia, the air was…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: DEA & FBI CRUSH ALLEGED CARTEL TRUCKING EMPIRE — HIDDEN ROUTES MAPPED, DRIVERS DETAINED, AND MILLIONS STACKED AS EVIDENCE 🚨 Before sunrise, highways turned into a grid of flashing lights as agents intercepted rigs, cracked open trailers, and traced coded dispatch logs, revealing what officials describe as a logistics web hiding in plain sight behind ordinary freight lanes 👇

The Fall of Shadows: A Cartel’s Empire Exposed In the dimly lit corridors of power, where shadows danced with deceit,…

🚢 U.S. NAVY TRAPS SINALOA CARTEL’S ALLEGED $473 MILLION “DRUG ARMADA” AT SEA — AND THE HIGH-STAKES STANDOFF UNFOLDS UNDER FLOODLIGHTS AND ROTOR WASH 🚢 Radar screens lit up, cutters boxed in fast boats, and boarding teams moved with clockwork precision as authorities described a sweeping maritime interdiction that turned open water into a chessboard, stacking seized cargo on deck while prosecutors hinted the ripples would travel far beyond the horizon 👇

The Abyss of Deceit: A Naval Reckoning In the heart of the Caribbean, where the turquoise waters glimmered under the…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: DEA & FBI DESCEND ON MASSIVE TEXAS LOGISTICS HUB — 52 TONS OF METH SEIZED AS 20 POLITICIANS ALLEGEDLY TIED TO A SHADOW NETWORK ARE THRUST INTO THE SPOTLIGHT 🚨 What began as a quiet federal probe detonated into a sweeping raid of warehouses and boardrooms, with agents hauling out towering stacks of evidence while stunned insiders whisper that the real shockwave isn’t just the drugs — it’s the powerful names now facing intense scrutiny 👇

Shadows of the Underground: The Texas Cartel Unveiled In the heart of Texas, where the sun sets over sprawling landscapes,…

End of content

No more pages to load