Researchers Zoomed In On This Enslaved Boy’s Eyes—What They Discovered Was Impossible to Forget

Researchers zoomed in on this enslaved boy’s eyes.

What they discovered was impossible to forget.

Dr.James Mitchell had been studying Annabellum photography for 15 years, and he thought he had seen everything.

The dgeray types, amber types, and early paper photographs from the 1850s and 1860s had become so familiar to him that he could date most images within a year or two just by examining the clothing, photographic techniques, and wear patterns on the plates.

But on a cold February morning in 2024, sitting in his office at the University of Virginia, he encountered a photograph that would change everything he thought he understood about bearing witness to history.

The image had arrived as part of a larger collection donated by the estate of a Virginia family whose ancestors had owned one of the largest plantations in Alamar County before the Civil War.

Most of the collection was unremarkable.

formal portraits, landscape views, documentation of property and buildings, standard fair for wealthy antibbellum families, trying to project an image of respectability and permanence.

Then James opened a small wooden case containing a dgeray type that made him stop breathing for a moment.

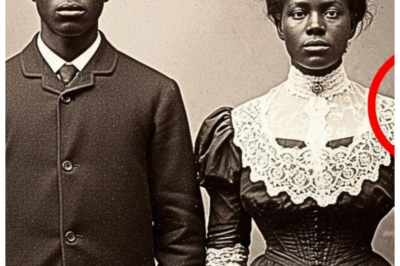

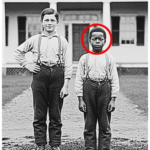

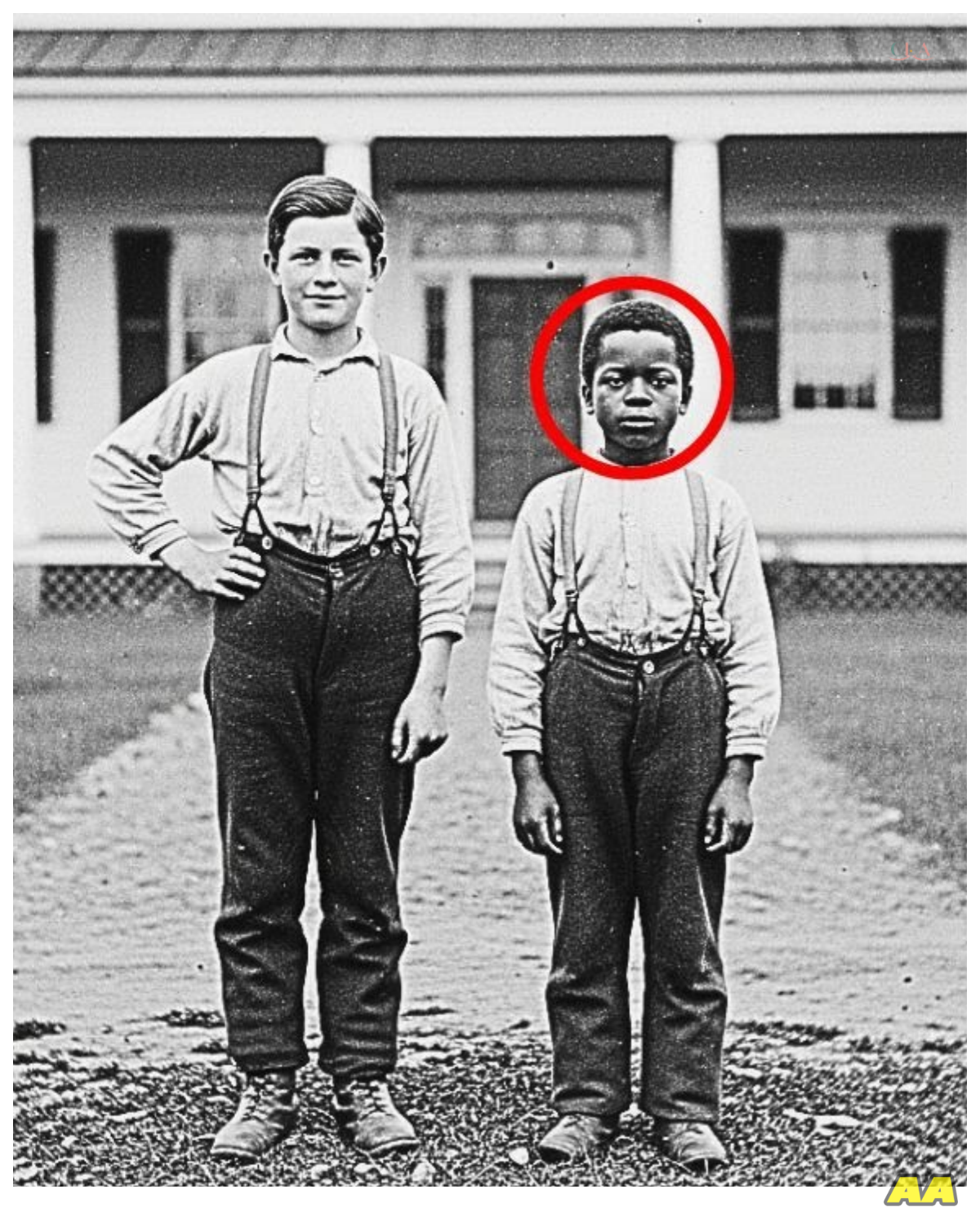

The photograph showed two boys, both approximately 12 years old, standing side by side in what appeared to be the front yard of a grand plantation house.

White columns were visible in the soft focused background along with manicured gardens and a curved driveway.

The image was remarkably well preserved.

The silver surface still reflecting light after more than 160 years.

The two boys were dressed almost identically.

Both wore simple cotton shirts, dark trousers held up by suspenders and heavy work boots.

Their clothes were clean but showed signs of wear.

At first glance, someone unfamiliar with antibbellum photography might have assumed they were brothers or playmates of similar social standing.

But James knew better.

He could read the subtle but deliberate differences that marked one boy as free and the other as enslaved.

The white boy stood on the left, his posture confident and relaxed.

His face was turned directly toward the camera, meeting the lens with an open, almost defiant gaze.

His expression conveyed entitlement, the unconscious assumption that the world existed for his benefit.

One hand rested casually on his hip.

Everything about his bearing communicated ownership, not just of the space around him, but of the moment itself.

The black boy stood to the right, positioned slightly behind and lower, as though the ground beneath him sloped downward.

His posture was rigid.

Shoulders held at an unnatural angle.

Arms pressed tightly against his sides.

His clothes, while similar in style, fit differently, slightly too large, handed down or made without careful measurement.

But it was the boy’s face that seized James’ attention.

Unlike the white boy, the enslaved child did not look at the camera.

His face was turned approximately 30° to the right, his gaze directed at something beyond the frame.

His expression was carefully neutral, almost blank.

James had seen this expression before in dozens of photographs of enslaved people.

It was a mask of survival.

James couldn’t stop looking at the photograph.

He cleared his desk of other work and positioned the dgeraype case under his high-intensity examination lamp.

He pulled out his jeweler’s loop and began studying every millimeter of the image, noting details that might provide context, identification, or dating information.

On the back of the case, he found an inscription in faded ink.

Thomas and Samuel, Riverside Plantation, April 1858.

The handwriting was elegant, practiced, probably written by someone educated, someone who had the luxury of learning penmanship, while others worked the fields.

Thomas and Samuel, the white boy and the enslaved boy, given names, preserved in silver and glass, frozen in a moment that had occurred 166 years ago.

James turned his attention back to the image itself.

The photographic technique was sophisticated for 1858.

The exposure was even, the focus sharp in the center where the boy stood.

Whoever had taken this photograph knew their craft.

The lighting suggested early morning or late afternoon when the sun was lower and softer, ideal for portraiture.

But why had this photograph been taken? What was its purpose? James had studied enough antibbellum photography to know that images like this were relatively rare.

Photographs were expensive, requiring specialized equipment and expertise.

Most plantation owners commissioned formal portraits of themselves and their families, documentation of their grand houses, or occasionally images of prized horses or hunting dogs.

Enslaved people appeared in photographs primarily as background elements, as markers of wealth, or as property to be cataloged and inventoried.

But this photograph was different.

The two boys were clearly the subjects positioned centrally and deliberately.

They were dressed similarly, standing close together.

Yet everything about the composition emphasized their fundamental inequality, the white boy’s direct gaze versus the black boy’s averted eyes, the subtle difference in positioning, the body language that spoke volumes about power and subjection.

James reached for his phone and called his colleague Dr.

Maya Thompson, a historian specializing in slavery and the lived experiences of enslaved children.

She answered on the third ring.

Maya, I need you to come to my office, James said without preamble.

I found something that I think is important.

A photograph from 1858.

Two boys, one enslaved, one free.

There’s something about it that feels significant, but I can’t quite articulate why.

I’ll be there in 20 minutes, Maya replied, hearing the urgency in his voice.

While he waited, James continued examining the photograph.

He noticed that the enslaved boy’s hands were clenched into fists at his sides, the knuckles prominent, even through the slight blur of the dgeray process.

The white boy’s hands were relaxed, open, even their hands told a story about freedom and captivity, about ease and tension.

When Maya arrived, James handed her the photograph without explanation, wanting her unfiltered first impression.

She studied it in silence for several minutes, her expression growing more troubled.

Finally, she looked up at James, her eyes bright with emotion.

“Do you see his eyes?” she asked quietly.

The enslaved boy, Samuel.

Yes, look at where he’s looking.

He’s not just looking away from the camera.

He’s looking at something specific.

Maya positioned the Dgerayotype under James’ digital microscope, a sophisticated piece of equipment capable of capturing highresolution images of historical photographs without damaging them.

She adjusted the focus, zooming in on Samuel’s face, specifically on his eyes.

The thing about dgerayotypes, Maya explained as she worked, is that they’re incredibly detailed.

The silver surface captures nuances that later photographic processes couldn’t match.

If we can get a clean digital capture of his eyes, we might be able to see what he was looking at.

James watched over her shoulder as the image appeared on the computer screen.

Maya zoomed in further, the pixels resolving into startling clarity.

Samuel’s eye filled the screen, the iris, the pupil, the slight reflection of light on the corial surface.

And there in that reflection was something neither of them had expected.

“Oh my god,” Maya whispered.

The reflection in Samuel’s eye showed figures, people, a group of people standing in what appeared to be a line positioned some distance away from where the photograph was being taken.

Even in the tiny reflection, captured inadvertently by the dgerotype process, they could make out details, light colored clothing, the postures of people standing and waiting, the suggestion of a crowd.

“That’s an auction,” James said, his voice hollow.

“That’s a slave auction happening while this photograph was being taken.

” Maya nodded slowly, her jaw tight.

Samuel wasn’t just looking away from the camera randomly.

He was watching people being sold, people he probably knew, maybe people he loved.

They sat in silence for a moment, the weight of the discovery settling over them like a physical presence.

This photograph, which had seemed like a straightforward, if uncomfortable, documentation of antibbellum social hierarchy, was actually something far more complex and devastating.

It was a record of forced witnessing of a child being made to observe the commodification and sale of human beings while he himself was being photographed as property.

“We need to enhance this,” Maya said decisively.

We need to see if we can get more detail from that reflection, and we need to find out everything we can about Riverside Plantation, about Thomas and Samuel, and about what happened there in April 1858.

Over the next week, James and Maya worked with a digital imaging specialist to create the highest resolution scan possible of the Dgeray.

The specialist used a process called focus stacking, taking hundreds of images at slightly different focal planes and then combining them into a single, incredibly detailed composite image.

When the final enhanced image was ready, they gathered in James’ office to examine it.

The imaging specialist, a graduate student named Alex, projected the image onto a large screen on the wall.

“I’ve never seen anything like this,” Alex said, clearly shaken by what they had uncovered.

The level of detail preserved in Dgeray types is remarkable, but this this is extraordinary and heartbreaking.

The enhanced reflection in Samuel’s eye revealed more than they had initially seen.

The auction was clearly visible now.

Approximately 20 people standing in a rough line with what appeared to be a platform or raised area where a man stood, presumably the auctioneer.

Off to one side were several white men in formal clothing, likely buyers.

The enslaved people waiting to be sold stood with various postures.

Some with heads bowed, others looking straight ahead, a few with children clinging to their legs.

“Can we identify any of them?” James asked.

“Not clearly enough,” Alex replied.

The reflection is still limited by the physics of optics and the resolution of the original Dgeray type, but we can see enough to know what’s happening.

Maya leaned closer to the screen.

Look at the ground near the auction.

Do you see that? James squinted.

There appeared to be objects on the ground.

Bundles perhaps, or bags.

Those are belongings, Maya said softly.

When enslaved people were sold, they sometimes were allowed to take a small bundle of possessions.

A change of clothes, maybe a blanket.

James and Mia knew they needed to find out who Samuel was.

not just his name, but his story, his life, what happened to him after this photograph was taken.

They began with the plantation records, hoping that the family who had donated the collection might have preserved documentation about the people they had enslaved.

They contacted the estate executive, a lawyer named Robert Whitfield, who represented the descendants of the original plantation owners.

Robert was initially hesitant to provide additional materials, citing privacy concerns for the family.

But when James explained the historical significance of their discovery, he agreed to grant them access to the plantation’s archives.

The archives were housed in a climate controlled storage facility outside Charlottesville.

James and Maya spent three days going through boxes of documents, ledgers, correspondents, bills of sale, inventory lists, and financial records.

The meticulous recordkeeping of the plantation’s operations was both invaluable for their research and deeply disturbing in its cold business-like documentation of human ownership.

They found the first mention of Samuel in a ledger from 1846.

Negro boy Samuel born March 1846 to Rose house servant healthy value estimated at $100.

Samuel had been born into slavery on Riverside Plantation.

His mother Rose was listed as a house servant which meant she likely worked in the main house rather than in the fields.

The ledger tracked Samuel’s growth and development like one might track livestock.

Notes about his health, his size, his aptitude for various tasks.

By 1858, when the photograph was taken, Samuel was 12 years old and listed as a yard boy and stable hand.

His monetary value had increased to $800, reflecting his age, health, and the skills he had developed.

But it was another document that provided the context they had been seeking.

A letter dated April 15th, 1858, written by the plantation owner, Colonel Richard Whitfield, to his brother in South Carolina.

Dear brother, the letter began, I am pleased to report that yesterday’s sale was most profitable.

We managed to move 18 head at favorable prices, including several prime field hands and a breeding woman with two children.

The market remained strong despite the economic uncertainties in the north.

I had young Thomas present for the auction, as I believe it essential that he learned the business of managing property and understand the natural order of things.

I also ensured that Rose’s boy Samuel was present as a reminder of what befalls those who might consider flight or disobedience.

The boy watched the entire proceedings with appropriate semnity.

The dgerayite man was here as well, capturing an image of Thomas with Samuel.

I believe it will serve as a useful record of Thomas’s education and responsibility.

Maya read the letter three times, her hands shaking with anger.

He made Samuel watched the auction as a threat, as a way to control him through fear.

And he had the photograph taken to commemorate Thomas’s education in the business of slavery.

James felt sick.

The photograph they had been studying wasn’t just documentation.

It was a tool of psychological torture, a deliberate reminder to an enslaved child of his powerlessness and the constant threat of separation from everyone he knew and loved.

“We need to find out if Rose was sold that day,” Maya said urg urgently.

“If Samuels mother was among those 18 people sold, they returned to the ledgers, searching for any record of Rose after April 1858.

” It took hours of cross referencing and careful reading, but finally they found it.

A bill of sale dated April 14th, 1858.

Rose had been sold to a plantation owner in Georgia for $600.

The notation beside her name read, “Good house servant, healthy, age approximately 28.

Samuel had watched his mother being sold.

He had stood there, 12 years old, and watched the only family he had ever known being taken away forever.

” And then, immediately after, he had been forced to stand beside his enslaver’s son and pose for a photograph.

With the knowledge that Samuel had witnessed his mother’s sale, James and Mia returned to the archives with renewed urgency.

They needed to understand the full escope of what Samuel had experienced that day, and they needed to find out what had happened to him afterward.

They located the complete auction records from April 14th, 1858.

The document was written in neat business-like handwriting, listing each person sold, their age, skills, physical description, and sale price.

Reading it felt like witnessing a crime.

Each line a violation of human dignity recorded with bureaucratic precision.

The 18 people sold that day included Rose, 28, House servant, sold to Mr.

Gerald Thompson of Savannah, Georgia for $600.

Samuel’s mother, Jacob, 42, Fieldhand, sold to Mr.

William Harrison of Richmond, Virginia for $950.

Mary, 35, Cook, sold with her two children, Daniel, 8, and Hannah, 6 to Mr.

Charles Morton of Charleston, South Carolina for $1,4100 total.

Elijah, 19, blacksmith, sold to Mr.

Robert Davis of Atlanta, Georgia, for $1,200.

The list went on.

Each name represented a person, a life, a network of relationships torn apart.

Several were sold as lots.

Mothers with children, siblings sold together to make them more marketable.

Others were sold individually.

Families deliberately separated to different states, making reunion impossible.

Maya created a database of all 18 people, noting where they were sold, and to whom.

If we can trace where they went, we might be able to find out what happened to them.

Some of them might have descendants who don’t know this part of their family history.

While Maya worked on tracing the sold individuals, James focused on finding more information about Samuel’s life after the auction.

What happened to a boy forced to watch his mother being sold? How did he survive the psychological trauma? Did he ever see Rose again? The plantation ledgers showed that Samuel continued working at Riverside for the next 3 years.

The entries were brief notations about his tasks, his health, his behavior.

In 1859, there was a note, Samuel attempted flight, recovered, punished.

The clinical language barely concealed the violence implied.

Samuel had tried to run away.

He had been caught and he had been punished, though the ledger didn’t specify how.

James had studied enough antibbellum history to know that punishments for attempted escape were brutal, designed to break the spirit and terrify others into submission.

But Samuel appeared in the records again in 1860, still working at Riverside, still surviving.

Then came 1861, and the records became sparse.

The Civil War had begun, and the orderly documentation of the plantation began to break down.

There were fewer entries, more gaps, notations about shortages and difficulties.

The world that had sustained Riverside Plantation was collapsing.

The final entry about Samuel appeared in March 1865.

Samuel departed with Union troops, whereabouts unknown.

As Samuel had left with Union soldiers when they came through Alamar County in the final months of the war, he had been 19 years old, finally free after a lifetime of enslavement.

But where had he gone? What had he done with his freedom? Had he ever found his mother? James and Maya knew they needed to search beyond the plantation wreck.

They needed to look at Freriedman’s bureau documents, military records, census data from the reconstruction era, anything that might tell them what became of Samuel after he walked away from Riverside.

The search took them weeks.

They combed through digitized records from the National Archives, contacted genealogologists who specialized in African-American family history, and reached out to historical societies across Virginia and Georgia.

Finally, they found him.

The breakthrough came from an unexpected source, a collection of letters housed at the Library of Virginia in Richmond.

The letters had been written by teachers and missionaries who had gone to the South during and after the Civil War to establish schools for formerly enslaved people.

One teacher, a woman named Elizabeth Hayes from Massachusetts, had written extensively about her experiences teaching in Virginia from 1865 to 1870.

In a letter dated June 1865, Elizabeth wrote about her students.

Among my pupils is a young man named Samuel, approximately 19 years of age, who demonstrates an extraordinary aptitude for learning.

He is determined to read and write, working long into the evening by candlelight.

When I asked him why he pushes himself so hard, he told me he is searching for his mother, who was sold away from him seven years ago.

He believes that if he can read and write, he can write letters to plantations throughout the South, inquiring after her.

He has memorized her name, her age, her description, and the name of the man who purchased her.

His determination is both inspiring and heartbreaking.

James read the letter aloud to Maya, his voice breaking on the last sentence.

Samuel hadn’t given up.

Even after seven years, even after everything he’d endured, he was still looking for Rose.

They found more references to Samuel and Elizabeth’s correspondents over the next few months, he had indeed begun writing letters, dozens of them, sent to plantations, churches, and Freriedman’s bureau offices throughout Georgia, asking if anyone knew of a woman named Rose, who had been sold from Virginia in 1858.

In September 1865, Elizabeth wrote, “Samuel received a response to one of his letters today.

A minister in Savannah wrote that he knows of a woman named Rose who matches the description Samuel provided.

She is working as a laundress and living in a small community of freed people near the city.

Samuel departed immediately, walking the nearly 500 miles to Georgia.

I gave him what money I could spare and prayed for his safe journey and for the reunion he has dreamed of for so many years.

Maya wiped tears from her eyes.

Did he find her? Please tell me he found her.

They searched through more documents, their hands shaking with anticipation and fear.

The answer came in a letter Elizabeth received in November 1865, forwarded from Samuel himself.

His handwriting was careful and unpracticed but legible.

Dear Miss Hayes, um, I found my mother.

She is alive and well.

When I saw her, she did not recognize me at first, as I have grown so much.

But then she knew my eyes, and she called my name, and we held each other and cried.

She thought I had been sold or killed during the war.

She thought she would never see me again.

Thank you for teaching me to write so I could find her.

I will never forget your kindness, your student, Samuel.

James and Mia sat in silence, overwhelmed by the emotional weight of what they had discovered.

This photograph, which had documented such trauma and oppression, was also part of a larger story of resilience, determination, and love that refused to be extinguished.

But their research was far from over.

They needed to know what happened next.

Did Samuel and Rose stay in Georgia? Did Samuel build a life for himself? Did he have a family? They continued searching, now focusing on Georgia records from the Reconstruction era.

They found Samuel again in the 1870 census living in Savannah.

He was listed as a carpenter living with Rose and a wife named Martha.

By 1880, the census showed two children, a daughter named Rose and a son named Elijah.

Samuel had named his daughter after his mother and his son after one of the people sold alongside Rose that day in April 1858.

He was keeping their memories alive.

As James and Maya pieced together Samuel’s post-emancipation life, they made another extraordinary discovery, one that would transform their understanding of who Samuel had been and what his life’s work had become.

In a collection of papers from a black church in Savannah, preserved by the local historical society, they found a notebook.

It was small, bound in worn leather, its pages yellowed and fragile.

The handwriting inside was the same careful script they had seen in Samuel’s letter to Elizabeth Hayes.

The notebook contained lists, pages, and pages of names organized by date and location.

Each entry included a name, an approximate age, a physical description, where the person had last been seen, and where they had been sold to.

Some entries had notes beside them, found in Atlanta, 1867, or reunited with sister in Charleston, 1869, or simply deceased.

“It took them several moments to understand what they were looking at.

” “He was documenting everyone,” Maya said, her voice filled with awe.

everyone who had been sold from Riverside and probably from other plantations, too.

He was trying to help people find their families.

The first page of the notebook began with the date, April 14th, 1858, the day of the auction Samuel had been forced to witness.

Listed there were the 18 people who had been sold that day.

Each entry meticulously detailed.

Rose, his mother, was the first name.

But the list continued far beyond those 18.

Page after page contained hundreds of names.

People Samuel must have heard about, learned about, or met during his travels.

He had been collecting information, creating a database of separated families and apparently helping people reconnect.

A letter tucked into the back of the notebook dated 1872 provided more context.

It was from a man named Robert writing to thank Samuel for helping him find his brother who had been sold to Louisiana before the war.

Because of your records and your assistance, Robert wrote, I was able to locate my brother after 14 years of separation.

He has children I never knew existed.

My family is whole again because of your dedication.

May God bless you for the work you do.

James and Maya found more evidence of Samuel’s work in other archives, references in Freriedman’s Bureau reports, mentions in church records, testimonials from people who had been reunited with loved ones through Samuel’s efforts.

Samuel had turned his trauma into purpose.

The auction he had been forced to witness as a 12-year-old boy, the separation from his mother, the years of searching for her.

All of it had shaped him into someone who dedicated his life to healing the wounds that slavery had inflicted on thousands of families.

“He remembered them all,” Maya said softly, turning the pages of the notebook.

Everyone who was sold that day, everyone he heard about, he remembered them and he wrote them down and he helped them find each other.

They found records showing that Samuel had traveled extensively throughout Georgia, South Carolina, and Florida during the 1870s and 1880s, always carrying his notebook, always collecting names and information, always helping people search for lost relatives.

In 1885, a newspaper article from the Savannah Tribune, one of the first African-American newspapers in Georgia, featured a story about Samuel’s work.

The headline read, “Local carpenter helps hundreds reunite with families torn apart by slavery.

” The article described Samuel as a quiet man of extraordinary dedication who carries with him a record of names and places that has helped countless freed people find relatives they believed were lost forever.

The journalist had asked Samuel why he did this work.

Samuel’s response, quoted in the article, brought tears to both James’s and Ma’s eyes.

When I was 12 years old, I watched my mother being sold.

I watched 17 other people being sold that same day.

I memorized every name, every face.

I promised myself that if I ever became free, I would find my mother.

And I did.

But there are thousands of people still searching, still hoping.

As long as I can help even one family find each other, I will keep doing this work.

Every name matters.

Every person matters.

No one should be forgotten.

James and Maya knew they had uncovered something profound.

Not just a historical discovery, but a story that needed to be shared with the world.

The photograph of 12-year-old Samuel, forced to witness an auction while posing beside his enslaver son, was powerful on its own.

But knowing what Samuel had done with the rest of his life, how he had transformed his trauma into a mission of reunion and healing elevated the story to something truly extraordinary.

They decided to present their findings at the annual conference of the Association for the Study of African-American Life and History scheduled for September 2024 in Charleston, South Carolina.

The location felt significant.

Charleston had been one of the largest slave trading ports in North America, a city where countless families had been torn apart.

Their presentation was scheduled for the main conference hall, and word had spread about the nature of their discovery.

When James and Maya arrived, they found the room packed with historians, genealogologists, descendants of enslaved people and journalists.

The energy in the room was palpable, anticipation mixed with semnity.

James began by displaying the original dgeraype on the large screens, explaining its providence and the initial details they had observed.

The audience studied the image in silence.

Thomas looking directly at the camera, Samuel looking away, the subtle but unmistakable markers of power and subjugation in their postures and positions.

Then Maya took over, walking the audience through their process of enhancing the image and discovering the reflection in Samuel’s eyes.

When the enhanced image appeared on the screen, showing the auction reflected in the boy’s gaze, the room erupted in gasps and whispers.

Several people openly wept.

Samuel was forced to watch his mother being sold, Maya said, her voice steady despite her own emotion.

He was 12 years old, and his enslaver made him witness this auction as a form of psychological control, as a reminder of what could happen to him.

And immediately after, he was made to pose for this photograph, standing next to his enslaver’s son, as if they were equals, as if what he had just witnessed hadn’t happened.

James then presented the documents they had found on the auction records, the letters from Elizabeth Hayes, Samuel’s own notebook filled with names.

He told the story of Samuel’s search for his mother, his successful reunion with her, and the decades he spent helping others find their separated family members.

Samuel didn’t just survive, James said.

He transformed his pain into purpose.

He remembered every name from that auction in 1858, and he spent the rest of his life making sure that other people weren’t forgotten, that other families had a chance to reunite.

The audience sat in stunned silence as James displayed pages from Samuel’s notebook on the screen.

the careful handwriting, the meticulous records, the notations about successful reunions.

And we estimate that Samuel helped reconnect more than 200 families during his lifetime.

Maya concluded, 200 families who might never have found each other without his dedication.

He turned witnessing into testimony, trauma into healing, forced memory into deliberate remembrance.

When they finished, the room erupted in applause that lasted several minutes.

People stood, many still crying, acknowledging not just the historical significance of the discovery, but the profound humanity of Samuel’s story.

During the question and answer session, a woman in the back of the room raised her hand.

She identified herself as Dr.

Lorraine Samuel, a genealogologist from Atlanta.

Samuel is my great great grandfather, she said, her voice shaking.

I grew up hearing stories about him, about how he helped people find their families.

But I never knew about the photograph.

I never knew about what he witnessed as a child.

Thank you for finding this, for telling his story.

After the presentation, dozens of people approached James and Maya.

Several were descendants of people whose names appeared in Samuel’s notebook.

Others were researchers who wanted to help trace more of the people Samuel had documented.

A documentary filmmaker asked about rights to tell Samuel’s story.

A museum curator from the Smithsonian inquired about acquiring the Dgeray type and notebook for their collection on African-American history.

In the months following the conference, Samuel’s story spread rapidly.

Major newspapers picked it up.

The New York Times, the Washington Post, the Guardian.

The photograph and the enhanced image showing the auction reflection were published widely, always with careful context about what they represented and what Samuel had done with his life afterward.

The story resonated deeply, particularly among African-Americans whose own family histories had been fractured by slavery.

Genealogy organizations reported a surge in people searching for enslaved ancestors, many inspired by Samuel’s determination to find his mother and help others do the same.

James and Maya were invited to speak at universities, museums, and community centers across the country.

They always emphasized that Samuel’s story wasn’t just about the past.

It was about resilience, about refusing to let trauma have the final word, about the power of remembering and documenting.

In June 2025, the city of Charlottesville, working with the University of Virginia and the descendants of Samuel, announced plans for a permanent memorial to be erected near the site of the former Riverside plantation.

The memorial would honor not just Samuel, but all the people whose names appeared in his notebook, the 18 sold in April 1858, and the hundreds more he had documented and helped reunite with their families.

The memorial was designed by a black sculptor from Richmond named Marcus Freeman.

It consisted of two main elements, a bronze statue of Samuel as an adult, sitting on a bench with his notebook open on his lap and a curved wall inscribed with names, all the names from his notebook that could be verified through historical records.

The dedication ceremony took place on a warm September morning, exactly 167 years after the photograph had been taken and the auction had occurred.

More than 500 people gathered, including dozens of Samuel’s descendants and descendants of people whose names appeared in his notebook.

Dr.

Lorraine Samuel, his great great granddaughter, spoke first.

She was a woman in her 60s, a professor of African-American history, and she carried herself with a dignity that reminded James of the determination he’d seen in Samuel’s own writings.

My great great-grandfather experienced one of the worst traumas imaginable, she began.

As a child, he was forced to watch his mother being sold and taken away from him.

He lived in bondage for seven more years after that, carrying that wound every day.

When freedom came, he could have chosen to try to forget, to bury the pain and never look back.

Instead, he chose to remember.

He chose to document.

He chose to help others heal.

That choice, to transform suffering into service, is his greatest legacy.

She paused, looking at the bronze statue of Samuel with his notebook.

He taught us that remembering is an act of resistance.

That documentation is sacred.

That every name matters, every person matters, every family torn apart deserves to be made whole again if possible.

His notebook wasn’t just a list of names.

It was an act of love.

Maya spoke next describing the research process and what they had learned about Samuel’s life.

She read excerpts from his letters and from the testimonials of people he had helped.

Samuel’s story reminds us that history isn’t just dates and events, she said.

It’s people making choices about how to respond to injustice, about whether to let cruelty define them or to define themselves through their response to cruelty.

James concluded by returning to the photograph itself.

An enlarged version was displayed next to the memorial with a detailed explanation of what the image showed and what had been discovered in Samuel’s eyes.

On this photograph was meant to document white supremacy, James said.

It was meant to show a black child in his place, subservient and controlled, standing next to the white child who would grow up to be his master.

But Samuel refused to play that role even in a photograph.

He looked away.

He looked at what he was being forced to witness.

And in doing so, he created a record of truth that survived 167 years.

He turned their tool of oppression into his tool of testimony.

After the speeches, people walked slowly around the curved memorial wall, searching for names they recognized, ancestors, relatives, people whose stories they had heard in family histories.

Some placed flowers at the base of the wall.

Others took photographs or made rubbings of particular names.

The bronze statue of Samuel became a focal point with people sitting on the bench beside him, touching his hand, leaving small tokens and notes.

As the afternoon wore on and the crowd began to thin, James and Ma stood together in front of the memorial, watching the sun set behind the trees.

“He did it,” Mia said softly.

He made sure they weren’t forgotten.

200 families reunited, hundreds of names preserved, his mother found, his own children raised in freedom.

“He did it!” James nodded, thinking about the 12-year-old boy in the photograph, forced to witness horror, his eyes capturing a moment of unspeakable cruelty.

And then thinking about the man that boy became, determined, compassionate, relentless in his mission to heal what slavery had broken.

The photograph was supposed to teach Thomas about owning people, James said.

Instead, it ended up teaching all of us about Samuel, about dignity, resistance, and the power of refusing to forget.

They stood in silence as darkness fell.

The memorial lights illuminating the names on the wall and the bronze figure of Samuel with his notebook.

Forever documenting, forever remembering, forever bearing witness.

A year after the memorial dedication, James and Maya published their complete research in a comprehensive book titled The Boy Who Witnessed Samuel’s story and the power of remembrance.

The book included reproductions of the Dgerara type, transcriptions of Samuel’s notebook, historical context about slavery and family separation, and reflections on how collective memory shapes our understanding of justice and healing.

The book became a bestseller used in classrooms across the country.

It sparked conversations about how slavery’s legacy continued to affect African-American families, about the importance of genealological research and documentation, and about the role of memory in confronting historical trauma.

But the most profound impact came from something unexpected.

Inspired by Samuel’s Notebook, a coalition of genealogologists, historians, and descendants of enslaved people launched the Samuel Project, a massive collaborative database designed to help people trace family connections severed by slavery.

The project used modern technology, DNA testing, digitized records, artificial intelligence to scan historical documents, combined with the human dedication that Samuel had exemplified.

Within 2 years, the Samuel project had helped more than 3,000 people find information about enslaved ancestors.

Some discoveries were simple, a name, a location, a date.

Others were profound reunions between branches of families that had been separated for generations.

James and Maya continued their work, consulting with the project, and pursuing other research into the lives of enslaved people.

But they always kept the dgeray of Thomas and Samuel on display in James’ office, a reminder of why they did this work.

One afternoon, James received an unexpected visitor, a man in his 30s, who introduced himself as Thomas Whitfield, the great great great grandson of the Thomas in the photograph.

“I’ve been struggling with what to say,” Thomas admitted, sitting across from James’ desk.

“My family has a complicated relationship with our history.

Some members want to pretend the past didn’t happen.

Others acknowledge it, but don’t want to talk about it publicly.

” “But I needed to come here and say something.

” James waited, giving him space to gather his thoughts.

“That photograph is of my ancestor and Samuel standing together.

” Thomas continued, “My ancestor was being taught to see Samuel as property, as less than human.

But Samuel’s eyes were looking at something else, at truth, at injustice, at a reality my ancestor was supposed to ignore.

And then Samuel spent his life making sure that truth couldn’t be ignored.

That the people my family and others like us had treated as property were remembered as human beings with names and families and stories.

” Thomas paused, his voice thick with emotion.

“I can’t undo what my ancestors did.

I can’t change the past, but I can acknowledge.

I can learn from Samuel’s example about the importance of witnessing, of documenting, of remembering.

And I can commit to making sure my children know this history.

All of it, not just the sanitized version.

He pulled out an envelope and handed it to James.

This is a donation to the Samuel Project in Samuel’s name and in my ancestors name.

I know it doesn’t balance any scales or make anything right, but it’s something.

After Thomas left, James opened the envelope.

The check was for $50,000.

James immediately contacted Dr.

Lorraine Samuel to tell her about the donation and to see if she wanted to be involved in how it was used.

They decided together that the money would fund scholarships for descendants of enslaved people pursuing graduate degrees in history, genealogy, or archival work, training the next generation to do the work Samuel had begun.

The photograph that had started this entire journey, the dgeray of two 12-year-old boys, one free and one enslaved, one looking at the camera and one looking away, had become more than a historical artifact.

It had become a catalyst for confronting painful truths, for healing broken connection, and for ensuring that the people who had been treated as property were finally recognized as the human beings they had always been.

Every name mattered, every person mattered.

No one should be forgotten.

That was Samuel’s message preserved in the reflection in his eyes, documented in his careful handwriting, embodied in his decades of dedicated work.

And now, more than 160 years after that photograph was taken, his message was finally being heard by thousands of people working to heal the wounds that slavery had inflicted.

Samuel had looked away from the camera that day in April 1858, refusing to participate in the narrative his enslavers wanted to create.

Instead, his eyes had captured a different truth.

A truth about family separation, about trauma, about witnessing.

But his life had created another truth, too, about resilience, about transformation, about love that refused to be extinguished by cruelty.

The boy in the photograph had grown into a man who remembered.

And in remembering, he had helped hundreds of people find their way home to each other.

That was a legacy impossible to forget.

News

A 1904 Studio Photo Looks Harmless — But the Girl’s Hands Reveal a Frightening Detail A 1904 studio photo looks harmless, but the girl’s hands reveal a frightening detail. Professor David Richardson carefully arranged the collection of vintage photographs on his desk at the Boston Historical Archive. Each one a window into America’s past. The late afternoon sun filtered through the tall windows of his office, casting golden light across the sepia toned images that had arrived that morning from the Peton estate sale. Among dozens of typical family portraits from the early 1900s, one photograph immediately caught his attention. Not for any obvious reason, but for its seeming perfection, the 1904 studio portrait showed a young girl, perhaps 12 or 13 years old, seated in an ornate Victorian chair against a painted backdrop of pastoral scenery. She wore a pristine white dress with delicate lace trim, her dark hair arranged in the elaborate ringlets fashionable for children of wealthy families.

A 1904 Studio Photo Looks Harmless — But the Girl’s Hands Reveal a Frightening Detail A 1904 studio photo looks…

During the restoration, experts found a hidden detail in the slave girl’s clothing no one saw before During the restoration, experts found a hidden detail in the slave girl’s clothing no one saw before. Dr.Sarah Chen carefully positioned the dgerotype under the digital microscope, her breath shallow with concentration. The image before her was haunting. A young black girl, no more than 12, standing rigid beside a well-dressed white man in front of a columned mansion. New Orleans, 1858. The plate had arrived at the Smithsonian Conservation Lab 3 weeks ago, donated by an estate in Baton Rouge, and Sarah had been tasked with its restoration and authentication. The dgeray type was remarkably preserved. Its silver surface still reflecting light after 166 years. But something about the girl’s expression unsettled Sarah. While most enslaved people photographed in that era showed blank, emotionless faces, a defense mechanism against dehumanization, this girl’s eyes held something different. Not defiance exactly, but intention. Purpose.

During the restoration, experts found a hidden detail in the slave girl’s clothing no one saw before During the restoration,…

🔥 Tatiana Schlossberg at 35: Cause of Death Revealed—What Her Husband Endured, How Her Children Were Shielded, and Why Her Low-Key Lifestyle Hid a Fortune No One Talked About 💥 Said with sharp, tabloid bite, the lead suggests the truth cuts deeper than headlines, as insiders hint at hospital corridors, late-night decisions, and a family scrambling to protect legacy while mourning a loss that money, status, and history couldn’t stop 👇

The Untold Tragedy of Tatiana Schlossberg: A Life Shattered Tatiana Schlossberg, a name that once resonated with promise and legacy,…

💔 Dad Didn’t Understand Why His Daughter’s Grave Kept Growing—Until a Hidden Truth Shattered Him and Exposed a Silent Ritual That Left Him Collapsing in Tears at the Cemetery Gates 😭 The narrator whispers with cruel suspense, hinting that what began as confusion turned into a devastating revelation, as the father learns strangers had been secretly visiting, leaving objects, soil, and symbols that transformed grief into a haunting testament of love he never knew existed 👇

The Unraveling of a Legacy Tatiana Schlossberg was not just a name; she was a symbol of a storied lineage,…

End of content

No more pages to load