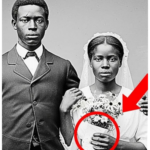

It was just a portrait of newlyweds until you see what’s in the bride’s hand.

The afternoon light filtered through the tall windows of the Smithsonian National Museum of African-American History and Culture as historian Marcus Thompson carefully sorted through boxes of 19th century photographs.

His hands, gloved in white cotton, moved with practiced precision as he examined each fragile image, documenting them for the museum’s upcoming exhibition on the reconstruction era.

Marcus had spent 15 years studying this turbulent period of American history.

The years immediately following the Civil War when formerly enslaved people fought to build new lives amid violence, discrimination, and broken promises.

Each photograph he handled represented a triumph.

Black families who had survived, who had claimed their freedom, who had dared to be documented at a time when their very existence was an act of defiance.

He reached for another photograph, this one protected in a yellowed envelope marked Charleston, SC, 1868.

As he slid it out, his breath caught.

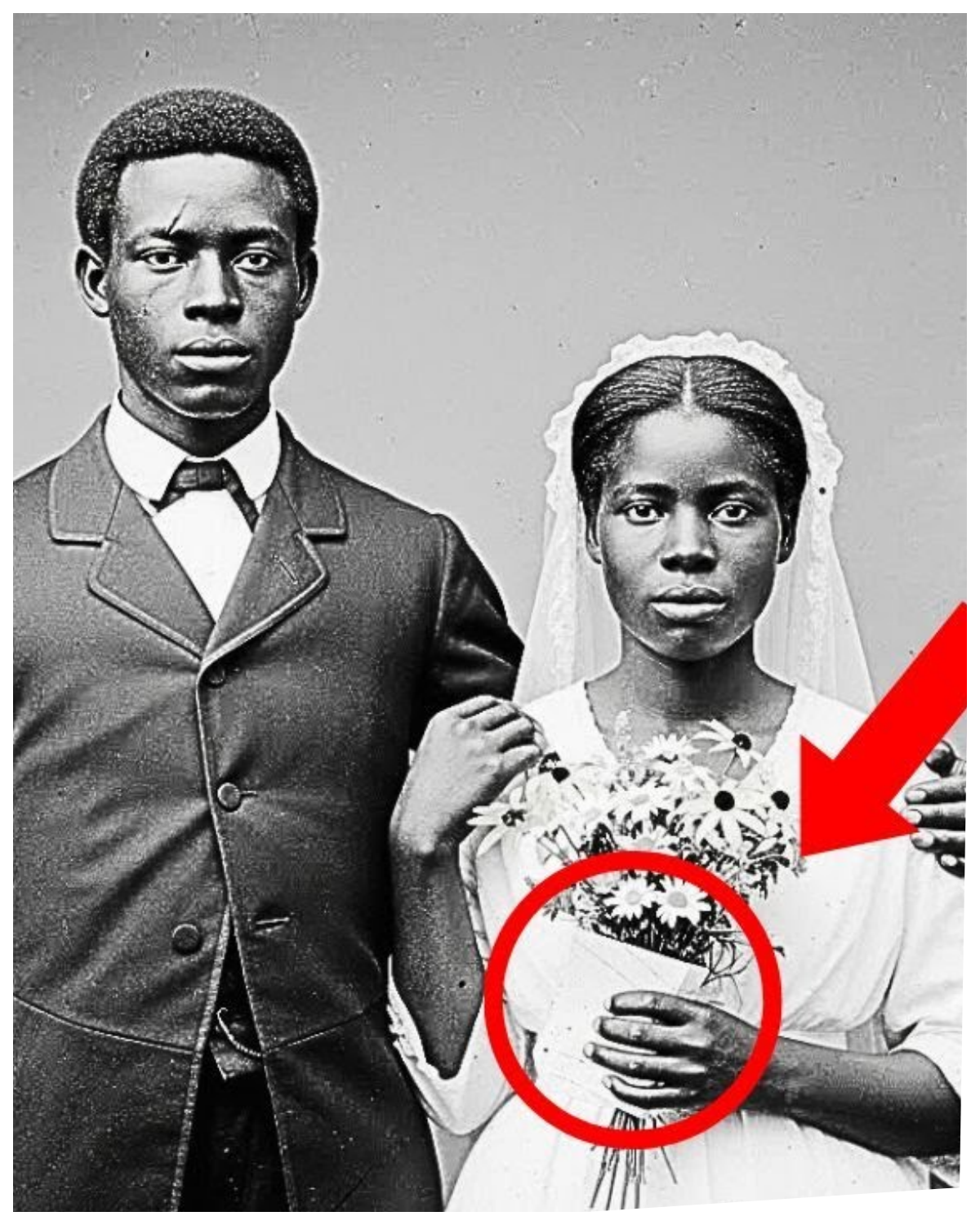

The image showed a young black couple on their wedding day.

The groom stood tall and dignified in a dark suit that appeared slightly too large, his hand resting protectively on the shoulder of his bride.

She sat before him in a simple white dress, her face radiant with hope and determination, clutching a small bouquet of wild flowers.

Marcus had seen hundreds of wedding portraits from this era, but something about this one made him pause.

There was an intensity in the bride’s eyes, a subtle tension in the way her fingers gripped the flowers.

He placed the photograph under his digital scanner, adjusting the settings to capture every detail.

As the highresolution scan appeared on his computer screen, Marcus began examining it section by section, zooming in to check for damage or interesting details.

He moved across the groom’s face, noting the faint scar above his eyebrow.

He examined the backdrop, a painted scene suggesting classical elegance.

Then Marcus zoomed in on the bride’s hands and bouquet.

His cursor hovered as he increased magnification.

There, barely visible between the wildflower stems, was something unexpected.

A small piece of paper folded tightly, tucked carefully among the blooms.

It was so subtle that anyone glancing at the original would have missed it entirely.

Marcus leaned closer, his heart racing.

In his years of research, he had learned that during reconstruction, nothing was simple.

Every image held potential for hidden stories.

Stories of survival, resistance, and courage deliberately concealed from those who would destroy them.

His fingers trembled as he saved the image.

Whatever that paper was, it had been important enough for this bride to hide in her wedding bouquet, to preserve in what might be her only photograph.

Marcus reached for his phone.

This discovery warranted investigation.

The next morning, Marcus arrived at the Charleston Historical Society before opening.

The director, Mrs.

Eloise Patterson, had agreed to meet him early after hearing the urgency in his voice.

She had spent 40 years preserving the city’s complex history and understood that sometimes a single photograph could unlock buried stories.

“You said you found something unusual?” Mrs.

Patterson asked as she led Marcus through quiet halls toward the research room.

Marcus opened his laptop and showed her the enhanced wedding portrait.

“This couple married in Charleston in 1868.

I need to find who they were and what this paper might be.

” Mrs.

Patterson adjusted her glasses and studied the screen.

Her expression shifted from curiosity to recognition.

1868 was significant here.

The constitutional convention had just granted black men voting rights.

Black legislators served in state government for the first time, but it was also tremendously violent.

The Kulux Clan was terrorizing black communities throughout the South.

She moved to a filing cabinet, searching through index cards.

Her meticulous cataloging system developed over decades.

Wedding portraits from that era are rare for black couples.

Photography was expensive, and most freedman struggled to survive.

If they had this photograph taken, it meant something.

Marcus watched as she pulled cards, cross- referencing dates and locations.

We have letters and documents from Charleston’s black community during reconstruction.

Many were donated by descendants wanting to preserve family histories.

She retrieved three leatherbound boxes from climate controlled storage.

Inside were fragile letters, newspaper clippings, church records, and personal documents that had survived fires, floods, and deliberate destruction.

They worked silently for nearly an hour.

Then Mrs.

Patterson made a small sound of discovery.

Here, she said, holding up a faded church registry.

Mount Zion Church, May 1868.

A marriage between David and Clara.

Marcus read the elegant handwriting.

The entry was simple.

David Freriedman, age 24, formerly of Virginia, and Clara, freed woman, age 22, formerly of Georgia, joined in holy matrimony.

No last names, Marcus observed.

Many formerly enslaved people had not yet taken surnames in 1868.

Mrs.

Patterson nodded.

Common, but look at this notation in the margin.

She pointed to a small symbol, a five-pointed star drawn next to their names.

Marcus’ pulse quickened.

What does that mean? I’m not certain, Mrs.

Patterson admitted.

But I’ve seen this symbol before in other documents from this period, always associated with what historians believe was an underground network.

People helping freed men navigate reconstruction’s dangers.

She pulled out a thin folder marked coded communications.

Inside were photocopies of documents containing hidden messages or symbols used by black communities to communicate secretly during the dangerous postwar years.

There, she said, pointing to a letter from 1867.

The same five-pointed star appeared in the corner.

This was intercepted by authorities who suspected sedicious content, but they never decoded it.

Marcus photographed the letter and registry.

Can you tell me about Mount Zion Church? Mrs.

Patterson smiled.

Well, that’s a story worth knowing.

Mount Zion African Methodist Episcopal Church still stood on Calhoun Street, though the building Marcus approached that afternoon was not the original structure.

Mrs.

Patterson had explained that the first church burned in 1871, was rebuilt in 1880, damaged by an earthquake in 1886, and reconstructed again.

Yet, the congregation persisted, maintaining records and oral histories stretching back to the church’s 1866 founding.

Reverend James Hutchinson, a man in his 60s with silver hair and warm eyes, greeted Marcus at the door.

Mrs.

Patterson called ahead.

She said, “You’re researching a couple who married here in 1868.

That’s a period we’re especially proud of and protective of.

” Marcus understood the implicit warning.

The black church had always been more than worship.

It had been shelter, school, meeting place, and keeper of stories the wider world tried to erase.

“I’m trying to understand who they were and what they might have been involved in,” Marcus explained, showing the enhanced photograph.

“I believe they were part of something important, something hidden for over 150 years.

” Reverend Hutchinson studied the image.

Come with me.

He led Marcus downstairs to the church basement where air smelled of old paper and wood.

Filing cabinets and boxes lined walls containing records preserved through every disaster.

We’ve digitized some, but much remains original, the Reverend explained.

After the first church burned, our people became careful about recordkeeping.

Some things were coded, others were never written, only passed through oral tradition.

He opened a cabinet and removed a large leather book, its cover worn smooth.

This is our original membership book, Saved from the Fire.

It lists everyone who joined between 1866 and 1871.

Marcus watched as fragile pages turned.

Names appeared in neat columns, men and women who had walked from slavery into uncertain freedom, choosing this church as spiritual home and fortress against a hostile world.

Here, Reverend Hutchinson said, pointing to an April 1868 entry.

Clara, no surname yet, joined one month before her wedding.

and look at the notation.

Next to her name was the same five-pointed star.

“What does it mean?” Marcus asked, forming a theory.

The Reverend closed the book gently.

“But my grandmother told me stories.

She was born in 1920, but her grandmother lived through reconstruction.

According to our oral history, people in this congregation did dangerous work, work that couldn’t be spoken about openly.

They helped threatened freed men find safety.

They searched for family members sold during slavery.

They protected documents, proving black land ownership, preventing destruction or theft.

He paused, expression solemn.

They did this while white supremacist groups were lynching, burning, and terrorizing anyone challenging the old order.

The star was their symbol, a way of identifying each other without words.

Marcus felt history’s weight settling around him.

Clara was part of this network.

If she had that star next to her name, Reverend Hutchinson confirmed, then yes, she risked her life every day.

And if she hid something in her wedding bouquet, it was worth dying for.

Marcus spent the next week searching census records, land deeds, and death certificates, trying to trace David and Clara’s path after their wedding.

The task was complicated by reconstruction’s chaos.

Records were incomplete, names inconsistent, and many documents had been deliberately destroyed by officials opposing Black Progress.

Finally, in a 1904 Charleston Cemetery Registry, he found Clara’s death record.

She had lived to 58, impressive for the time.

More importantly, the record listed survivors, three children and seven grandchildren.

Marcus now had names to trace forward.

It took three more days, but eventually he found a descendant still living in Charleston, Dorothy Jenkins, age 73, who according to records was Clara’s great great granddaughter.

Marcus called the number, his heart pounding.

Hello.

The voice was warm and cautious.

Miss Jenkins, my name is Marcus Thompson.

I’m a historian researching the reconstruction era and I believe I found a photograph of your great great grandmother Clara.

Would you be willing to speak with me? Long silence.

Then you found a picture of her? A real picture? Yes, ma’am.

Her wedding portrait from 1868.

Another pause.

Come to my house tomorrow at 2.

I’ll make tea.

Dorothy Jenkins lived in a modest North Charleston house.

Its front porch decorated with flowering plants and a wooden bench.

She opened the door before Marcus could knock, her face showing curiosity and something like relief.

“I’ve been waiting my whole life to know more about her,” Dorothy said, ushering Marcus inside.

“All we had were stories, fragments passed down.

My grandmother used to say Clara was a hero, but she could never explain exactly what she did.

” The living room was filled with family photographs spanning generations.

Marcus noticed many older portraits featured people with the same intense, determined gaze he had seen in Clara’s eyes.

He opened his laptop and showed Dorothy the wedding photograph.

The elderly woman’s hands flew to her mouth, tears immediately filling her eyes.

“Oh my lord,” she whispered.

“There she is.

There’s Clara.

” They sat in silence while Dorothy composed herself.

“I’m sorry, it’s just we’ve never seen her face before.

We knew she existed.

We knew she mattered, but she was always just a name in stories.

” Marcus zoomed in on the folded paper hidden in the bouquet.

“Miss Jenkins, I believe Clara was involved in something significant during reconstruction, something dangerous.

Do you know anything about her activities? Dorothy stood and walked to an old secretary desk.

She removed a small wooden box worn smooth with age.

This box has been passed down for five generations.

My grandmother gave it to my mother.

My mother gave it to me.

Inside are things Clara wanted preserved, though we’ve never fully understood what they meant.

She opened the box carefully.

Inside were several items.

A faded ribbon, a small brass button, a pressed flower, and several pieces of paper covered in names and locations written in careful script.

We always thought these were family records, Dorothy explained.

Marcus examined the papers with gloved hands.

But these weren’t family records.

They were addresses scattered across South Carolina and Georgia with names and small notations.

Safe.

Two rooms.

Reliable.

Doctor nearby.

Miss Jenkins.

Marcus said slowly.

I think these are safe houses.

With Dorothy’s permission, Marcus photographed every item in the box and took detailed notes.

He promised to share everything he learned about Clara’s life and ensure her story was told with dignity.

As he prepared to leave, Dorothy disappeared into another room and returned with a small bundle wrapped in cloth.

“There’s one more thing,” she said.

“Letters.

My grandmother told me Clara wrote letters to someone during the 1870s, and some survived.

We’ve kept them, but they’re fragile.

I’ve been afraid to handle them too much.

” Marcus unwrapped the cloth carefully, revealing letters tied with a faded ribbon.

The paper was brittle and brown, but the ink remained legible.

His hands trembled as he read the first, dated June 1870.

To my sister in faith, the situation grows more dangerous.

Three families left last week under darkness.

The night writers grow bolder, and we must be wiser.

The list must be kept updated.

Tell your people to watch for the star.

Marcus looked up.

Do you know who she was writing to? My grandmother said Clara had a friend, another woman who worked with her.

They were never specific about what work, but they said these two women saved many lives.

The friend’s name was Ruth.

Marcus continued reading.

Each letter contained coded language and veiled references, but together they painted a picture of a vast underground network spanning multiple states.

Clara and Ruth appeared central, coordinating safe passage for black families fleeing violence, maintaining lists of sympathetic allies, and warning communities about imminent white supremacist attacks.

One letter from 1872 was particularly striking.

Sister, we learned Morrison’s land deed was burned by the county clerk.

He has no proof of ownership now and they will take it.

I made a copy before the fire as we discussed.

It is hidden where we keep all such documents.

The truth must be preserved, even if it cannot yet be spoken.

Marcus felt a chill.

Clara hadn’t just been helping people escape.

She had been preserving evidence, legal documents, deeds, testimonies, anything proving black people’s rights and property.

In an era when such records were routinely destroyed to dispossess freed men, Clara had created a secret archive.

Miss Jenkins,” Marcus said carefully.

“These letters suggest Clara was hiding documents, important documents proving black land ownership and legal rights.

Do you have any idea where she might have kept them?” Dorothy shook her head slowly.

“If she did, that knowledge was lost.

” My grandmother used to say Clara took secrets to her grave, that some things were too dangerous to speak aloud even years later.

Marcus spent another hour recording Dorothy’s family oral histories.

As afternoon sun slanted through windows, he realized he was no longer just researching history.

He was uncovering extraordinary courage deliberately concealed from violent men who would have killed Clara if they had known.

When he left, Marcus carried copies of everything Dorothy had shared in a profound sense of responsibility.

Clara’s story deserved to be told properly with context and respect for the risks she had taken.

That evening, Marcus stared at the wedding photograph on his laptop.

The folded paper in Clara’s bouquet suddenly seemed even more significant.

What if it wasn’t just symbolic? What if it was a specific message meant to be preserved? He needed better technology and expertise he didn’t have.

He called a colleague at the Library of Congress.

Dr.

Patricia Reeves, a forensic document specialist, arrived at Marcus’ hotel the next morning with portable laboratory equipment.

She was a small woman with sharp eyes and infectious enthusiasm for solving historical mysteries.

Marcus had worked with her before on projects involving damaged or obscure documents, and he trusted her discretion and expertise.

So, you think there’s readable text on paper visible in an 1868 photograph? Patricia asked as she set up equipment on the desk.

That’s ambitious, Marcus.

Look at it yourself, he said, showing her the enhanced image.

You can see the paper’s edge clearly.

There’s writing on it.

Patricia examined the image through different filters and light spectrums on her computer.

After 15 minutes of silent work, she looked up with a grin.

You’re right.

There’s definitely text.

Let me see what I can do.

For two hours, Patricia applied various digital restoration techniques, adjusting contrast, enhancing specific light wavelengths, and using algorithms designed to make faded ink visible.

Marcus watched over her shoulder, barely breathing as letters began emerging on screen.

There, Patricia said finally, “That’s as good as I can get it.

” On the screen, the paper’s edge now showed clearly legible writing and cramped, urgent script.

Remember, first house on Rutled Road.

Ask for Samuel.

Star above the door, safe for families.

Tell Ruth all records hidden at Mount Zion beneath the stone marked faith.

Marcus stared at the words, his mind racing.

This was it.

The message Clara had hidden in plain sight, preserved in the one photograph that would endure.

She had known the photograph might be the only thing to survive her, and she had used it to leave a record of her network’s most crucial information.

“What does it mean?” Patricia asked, sensing the importance.

Marcus explained everything he had learned.

Clara’s involvement in the underground network, the safe houses, the hidden documents.

I think she was leaving instructions, a map essentially of where to find the people and places that mattered most.

And she was telling Ruth where to find the documents they’d been preserving.

Patricia’s eyes widened.

You mean there might still be a cache of documents hidden somewhere? Possibly.

Mount Zion Church was burned in 1871, just 3 years after this photograph was taken.

It was rebuilt.

But if Clare hid documents there, they could have been destroyed.

or Patricia suggested the new church was built over the same location and whatever Clara hid is still there buried beneath the floor.

Marcus immediately called Reverend Hutchinson.

The conversation was brief but electric with possibility.

The Reverend agreed to meet him at the church that evening to discuss what Marcus had discovered.

As the sun set over Charleston, Marcus stood once again before Mount Zion Church.

The building glowed warmly in evening light, its white walls bearing witness to more than 150 years of faith, struggle, and survival.

Reverend Hutchinson met him at the entrance, accompanied by three church elders, older congregation members who served as keepers of institutional memory.

Marcus showed them the enhanced photograph and the revealed text.

He explained his theory carefully, respectfully, acknowledging this was their church, their history, their decision.

The elders studied the image, speaking in low voices.

Finally, Mrs.

Grace Williams, the eldest at 87, spoke.

“My great-g grandandmother was a member here,” she said softly.

“She told me the old church, the one before the fire, had secrets worth protecting.

” “The church elders debated for nearly an hour.

Marcus sat quietly in a wooden pew, listening to their careful deliberation about whether to disturb the sanctuary floor in search of something that might no longer exist.

” He understood their hesitation.

This building was sacred space, and the decision to excavate required weighing historical curiosity against spiritual reverence.

Finally, Reverend Hutchinson approached Marcus.

We’ve decided to investigate, but we’ll do this carefully and respectfully.

If there’s evidence that Clara hid documents here to protect our people’s rights, then finding them honors her sacrifice rather than violates this space.

The next morning, a small team assembled at the church.

Marcus, Reverend Hutchinson, the three elders, and a professional preservation specialist recommended by the Charleston Historical Society.

They began by searching for any stone marked with the word faith anywhere in the building.

The current structure built in 1880 had a stone foundation and several commemorative stones embedded in the walls.

Mrs.

Williams led them to the basement where the oldest parts of the building remained.

“If anything survived the fire,” she explained, “it would be down here.

The flames destroyed the upper structure, but the foundation stones were reused when they rebuilt.

” They searched methodically, examining each stone for markings.

The basement was dim and cool, smelling of earth and age.

Marcus ran his fingers along rough stone surfaces looking for any carved words or symbols.

“Here,” called a preservation specialist, a woman named Dr.

Linda Hayes.

She was kneeling in a corner where the floor met the wall.

“Look at this.

” Marcus hurried over.

There, on a flat stone set into the floor, was a single word carved in simple letters.

Faith.

The stone was approximately 2 ft square, nestled among other foundation stones.

Unlike the others, this one had thin mortar lines around its edges, suggesting it could be removed.

Reverend Hutchinson knelt beside Dr.

Hayes, his hand resting gently on the stone.

“Before we proceed, let’s pray,” he said quietly.

The group gathered in a circle, and the reverend offered a prayer, asking for wisdom, respect for those who had come before, and guidance in honoring Clara’s legacy.

“Then Dr.

Hayes carefully worked to loosen the mortar around the stone’s edges.

The work was slow and delicate, requiring patience and precision to avoid damaging whatever might lie beneath.

Marcus’ heart pounded as the mortar gradually gave way.

Finally, after nearly two hours of careful work, the stone was loose enough to lift.

Reverend Hutchinson and Marcus together slowly raised it from its resting place.

Beneath, hollowed into the earth, was a metal box about the size of a small suitcase.

It was rusted but intact, sealed with wax that had hardened over the decades.

No one spoke.

The moment felt too significant for words.

Dr.

Hayes photographed the box in situ before carefully removing it from its hiding place and setting it on a clean cloth she had spread on the floor.

Clara put this here, Mrs.

Williams whispered.

She was right here in this spot, hiding these documents so they wouldn’t be destroyed.

And she left a message in her wedding photograph so someone would find them.

Marcus felt tears in his eyes.

The dedication, the foresight, the sheer courage it would have taken for Clara to do this, all while knowing that discovery could mean her death was overwhelming.

Dr.

Dr.

Hayes began the careful process of opening the sealed box.

The wax cracked and fell away.

The metal lid, though rusted, had protected the contents from moisture.

As she lifted it open, they saw what Clara had preserved.

Dozens of documents carefully wrapped in oiled cloth, still legible after more than 150 years.

The documents Clara had hidden represented an extraordinary collection of evidence from one of American history’s most turbulent periods.

As Dr.

Hayes carefully unwrapped each bundle.

A picture emerged of systematic resistance against the violence and dispossession that black communities faced during reconstruction.

There were land deeds, official documents proving that black families owned property.

Documents that county clerks and white supremacists had claimed were lost or destroyed.

Marcus counted 23 separate deeds, each one representing a family’s stake in freedom, their ability to build wealth and security.

Without these documents, those families would have lost everything.

There were marriage certificates, birth records, and military discharge papers for black soldiers who had fought in the Civil War.

These weren’t just family documents.

They were proof of citizenship of military service of legal standing that white authorities often refused to recognize.

There were also testimonies written in careful script describing acts of violence committed by white supremacist groups, names, dates, locations, evidence that could have been used for prosecution if the legal system had been willing to pursue justice.

Clara had documented these crimes even when she knew no immediate justice would come.

“This is remarkable,” Dr.

Hayes said, her voice filled with awe.

“This is a complete alternative archive, evidence that was supposed to be destroyed, preserved by someone who understood that truth matters, even if it can’t be acknowledged in the moment.

” “Reverend Hutchinson held one of the land deeds carefully.

” “The Morrison family,” he said, reading the name on the document, “I know descendants of that family.

They’re still in Charleston.

They’ve always been told their ancestors lost their land to unpaid taxes, that they never actually owned anything, as Williams was crying quietly.

How many families have lived for generations believing they had nothing when the truth was here all along, waiting to be found? Marcus understood the magnitude of what they had discovered.

This wasn’t just historical documentation.

This was restoration of truth, evidence that could potentially affect living descendants, proof that the stories passed down through black families weren’t myth or exaggeration, but documented fact.

Among the documents, they found lists in Clara’s handwriting.

One list contained names of people who had provided safe houses, complete with addresses.

Another listed sympathetic white allies, merchants who would hire black workers, lawyers who would file legal documents, doctors who would provide care regardless of ability to pay.

A third list documented children who had been separated from their families during slavery along with information about where they might be found.

“She was trying to reunite families,” Marcus said, his voice choked with emotion.

“Even while protecting legal documents and coordinating safe passage, she was trying to bring children back to their parents.

At the bottom of the box, wrapped separately, was a letter.

Dr.

Hayes lifted it carefully and unfolded it.

The handwriting was Clara’s, the same script Marcus had seen in the letters Dorothy had shown him.

It was dated December 1870 and addressed to whoever finds this truth.

Reverend Hutchinson read it aloud.

I am Clara Freedwoman and I write this so that someone in the future will know what we endured and what we preserved.

We are hunted for claiming what is rightfully ours.

Our documents are burned, our testimonies denied, our lives threatened for daring to be free.

But we will not be erased.

I have hidden here the proof of our rights, our marriages, our service, our ownership of land.

I’ve documented the crimes committed against us.

I have preserved the truth so that even if we cannot speak it now, it will be known someday.

To whoever finds this, tell our story.

Say our names.

Remember that we fought.

The basement was silent except for quiet weeping.

This was Clara’s voice across 150 years speaking directly to them, asking them to complete the work she had started.

The discovery of Clara’s archive created immediate practical and ethical questions.

Marcus, Reverend Hutchinson, and the church elders spent several days in careful discussion about how to handle the documents and the information they contained.

Some of the land deeds might have current legal implications for descendants.

The documented testimonies of violence named specific white families whose descendants still lived in Charleston.

The lists of allies and safe houses revealed information about people who had taken enormous risks, information that their descendants might not know.

Reverend Hutchinson convened a larger meeting of community members, including local historians, legal experts, and descendants of families mentioned in the documents.

Marcus presented his findings carefully, explaining how he had discovered the wedding photograph, traced Clara’s network, and ultimately found the hidden archive.

Dorothy Jenkins attended the meeting, sitting in the front row with tears streaming down her face as she finally learned the full extent of her great great-g grandandmother’s courage and impact.

“These documents belong to the community,” Reverend Hutchinson said firmly.

They represent our ancestors truth and we must decide together how to honor that truth while being mindful of the present.

The legal experts explained that some of the land deeds might be used to research property history and potentially support claims by descendants, though legal action would be complex and not guaranteed.

The historical value alone, however, was incalculable.

A descendant of the Morrison family, a man named Jerome, spoke through tears.

My grandfather always said we came from land owners, that we had something once.

Everyone told him he was wrong, that he was remembering stories incorrectly.

But he was right.

We did own land.

We weren’t just sharecroers or servants.

We owned something.

Marcus proposed a comprehensive approach.

The documents would be professionally preserved and digitized, then housed permanently at the Smithsonian National Museum of African-American History and Culture with copies available to the Charleston community.

The museum would create an exhibition telling Clara’s story and the broader story of reconstruction era resistance and preservation.

Additionally, Marcus would write a detailed historical account for academic publication.

And the church would host a community event where descendants could learn about their ancestors and access copies of relevant documents.

But we need to center Clara, Dorothy insisted.

This was her work, her courage, her vision.

The story isn’t just about documents.

It’s about a woman who risked everything to preserve truth.

Over the following weeks, Marcus worked with Patricia Reeves, Dr.

Hayes, and a team of archivists to carefully preserve, and document every item from Clara’s archive.

Each document was photographed, cataloged, and analyzed for historical context.

The wedding photograph took on new meaning.

What had started as a simple portrait of newlyweds was revealed to be a deliberate act of resistance and communication.

Clara’s way of ensuring that even if she died, even if the documents were never found, someone would know she had tried.

Marcus traced the house on Rutled Road mentioned in Clara’s Hidden Message.

The building no longer stood, but city records showed it had been owned by a black family named Samuel and Elizabeth throughout the 1870s.

Neighbors descendants remembered stories of the family helping people, though the details had been lost to time.

He found Ruth’s descendants as well.

Ruth had lived until 1895, continuing the network’s work long after Clara’s death.

Her great great-grandson, a professor at the College of Charleston, was stunned to learn about his ancestors role in the resistance movement.

We knew she was strong, he said.

We knew she had been through hardship, but we never knew she was a hero.

The stories were coming together, the fragments becoming whole, Clara’s carefully preserved truth finally being spoken.

6 months after the discovery, the Smithsonian unveiled its exhibition.

Hidden in plain sight, Clara’s archive and the reconstruction resistance.

The centerpiece was the wedding photograph displayed on a large screen where visitors could zoom in and see the folded paper in Clara’s bouquet with the revealed message displayed beside it.

Marcus stood in the gallery on opening day watching visitors move through the exhibition.

The walls displayed Clara’s documents or letters, lists of safe houses, and separated families.

Video screens showed interviews with descendants, including Dorothy Jenkins and Jerome Morrison, speaking about learning their family histories.

But the exhibition did more than showcase documents.

It told the human story of resistance during one of American history’s most dangerous periods.

It showed how ordinary people like Clara had created networks of protection and preservation.

How they had fought against eraser.

How they had kept truth alive even when speaking it meant death.

Dorothy approached Marcus, her eyes shining.

She would be proud, Dorothy said softly.

Clara hid the truth so it could be found.

And you found it.

You told her story.

Marcus shook his head.

I just uncovered what she preserved.

The courage was always hers.

The exhibition included a section on the impact of Clara’s archive.

12 families had been able to trace their property ownership back to the land deeds Clara had saved.

Historical societies across South Carolina were using her testimonies to document violence that had previously been denied or minimized.

Genealogologists were using her lists to help families find lost relatives, completing reunifications that Clara had started more than 150 years earlier.

Reverend Hutchinson had organized a service at Mount Zion Church to honor Clara and all the members of the congregation who had participated in the resistance network.

The church was packed with descendants of Clara, Ruth, Samuel, and dozens of others sitting together, finally able to speak their ancestors names with pride and full knowledge.

Marcus gave a talk at the museum, explaining how a single photograph had led to this discovery.

He spoke about the importance of looking closely, of asking questions, of understanding that history’s silences often hide stories of extraordinary courage.

Clara knew something that we sometimes forget.

Marcus said to the audience.

She knew that truth has power even when it can’t be spoken immediately.

She knew that preservation is resistance.

She knew that someone someday would care enough to look closely at her wedding photograph and ask why there was a folded paper in her bouquet.

He paused, looking at the image projected behind him.

Clara’s face still radiating determination after all these years.

She was right to believe in the future.

She was right to preserve the truth.

and she was right that her story and the stories of all those she protected deserve to be known.

As visitors moved through the exhibition, many stopped longest at the wedding photograph.

They leaned close to the screen, zooming in on Clara’s hands, seeing the paper tucked among the wild flowers, reading the message she had hidden there, a map to safety, a guide to truth, a bridge across time.

The photograph was no longer just an image of newlyweds.

It was evidence of courage, of strategic resistance, of a woman who had understood that even in the darkest times, truth could be preserved, and hope could be hidden in plain sight, waiting for the moment when it could finally be revealed.

Clara’s legacy lived on, not in monuments or grand memorials, but in the documents she had saved, the families she had helped reunite, the truth she had refused to let die.

Her wedding photograph, which she had used so cleverly to preserve her message, had finally delivered it to a world ready to listen, to learn, and to remember that ordinary people doing extraordinary things can change history, one carefully hidden truth at a

News

It was just a 1903 studio portrait — until you saw the strange symbols on the woman’s hand

It was just a 1903 studio portrait until you saw the strange symbols on the woman’s hand. Dr.Maya Richardson stood…

It Was Just a Photo of a Mother and Child — Until You Saw the Symbol Hidden in Her Fingers

It was just a photo of a mother and child until you saw the symbol hidden in her fingers. Dr.Maya…

No one ever noticed what was wrong with this 1930 family portrait — until it was restored

No one ever noticed what was wrong with this 1930 family portrait until it was restored. Jennifer Hayes carefully removed…

Why were Experts Turn Pale When They enlarged This Portrait of Two Friends from 1888?

Why did experts turn pale when they zoomed into this portrait of two friends from 1888? The digital archive room…

It was just a portrait of two sisters — and experts pale when they notice the younger sister’s hand

It was just a portrait of two sisters, and experts pale when they noticed the younger sister’s hand. The photograph…

🌲 VANISHED IN MONTANA — THREE YEARS LATER HIS BODY EMERGES WRAPPED INSIDE A DEAD TREE, AND THE FOREST SPEAKS A NIGHTMARE 🩸 What was thought to be another missing-person case turned into a grotesque revelation when hikers stumbled upon the hollowed trunk, realizing the wilderness had been hiding a chilling secret, and investigators were left piecing together a story of cruelty and concealment that sent shivers through the state 👇

The first thing people noticed was the silence. Not the peaceful kind that hikers chase, but the wrong kind, the…

End of content

No more pages to load