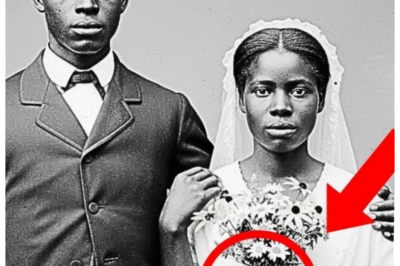

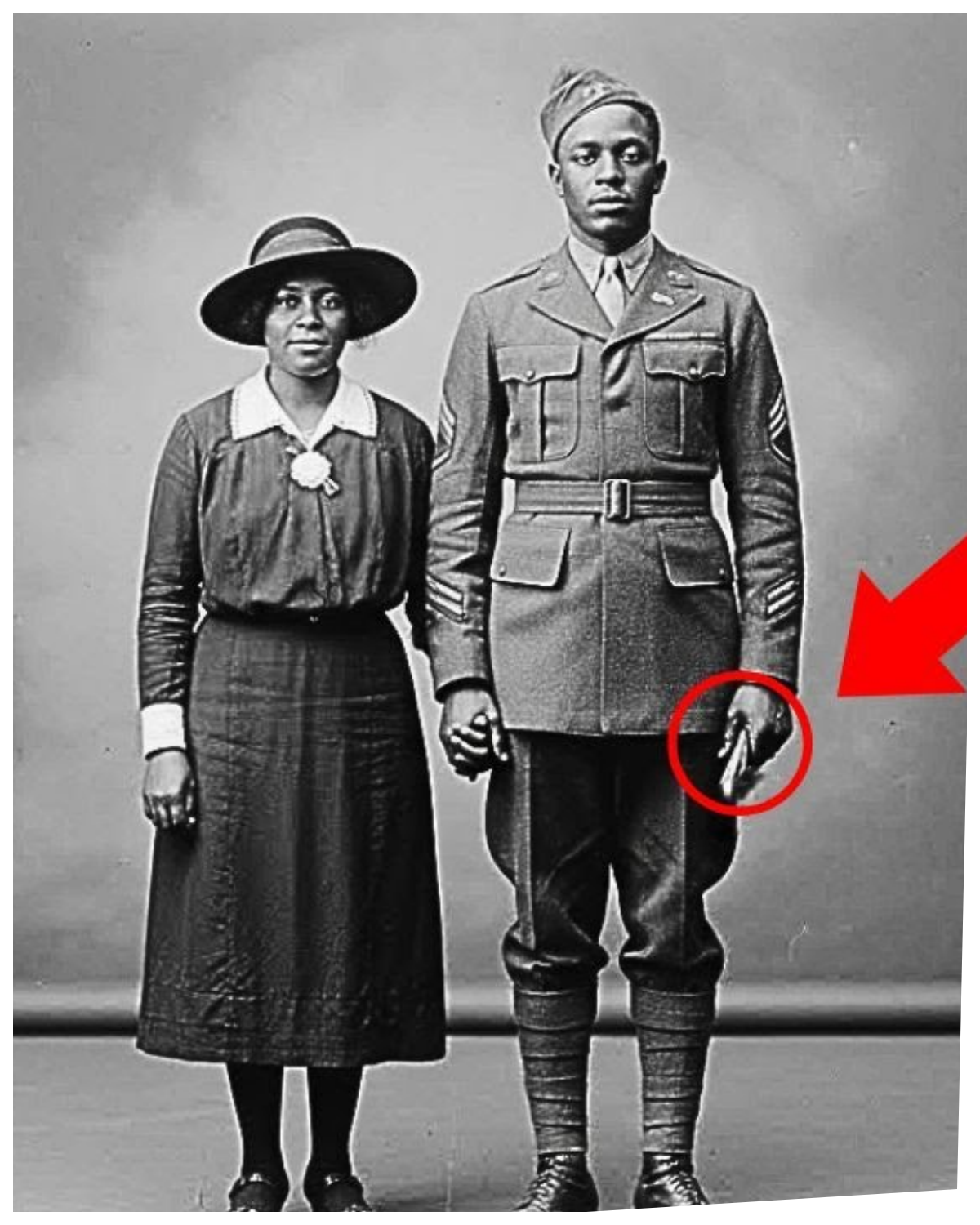

It was just a portrait of a soldier and his wife until you notice what he’s holding.

The photograph arrived at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History and Culture on a humid September morning in 2019.

Dr.Vanessa Brooks, a senior curator specializing in military history, carefully removed the bubble wrap surrounding the package.

Her practiced hands moving with the reverence she reserved for artifacts that might hold untold stories.

Inside Leia’s sepia toned portrait, its edges worn soft by time and the touch of countless hands across generations, depicting a black soldier in a crisp World War I uniform standing beside a young woman in her Sunday best.

The image bore the stamp of a photography studio in Harlem, New York, dated February 1919.

Vanessa felt her breath catch in her throat.

She knew exactly what that date meant.

It was the month the Harlem Hell Fighters came home from France.

The couple in the photograph seemed ordinary enough at first glance, indistinguishable from thousands of similar portraits taken during the era of homecomings and reunions.

The soldier stood tall and proud, his uniform immaculate despite the wear of a transatlantic journey, every button polished, every crease sharp.

Beside him, his wife, for the simple gold band on her finger confirmed their union, wore a modest dark dress and a wide-brimmed hat adorned with a single flower, her eyes shining with a mixture of profound relief and quiet joy.

They looked like any other couple, frozen in a moment of reunion after the horrors of war, grateful simply to be alive and together.

But something about the image nagged at Vanessa as she examined it under her desk lamp, something her trained eye couldn’t quite identify.

The accompanying letter explained that the photograph had been discovered in the basement of a demolished brownstone in Harlem, tucked inside a military foot locker alongside metals, letters, and a French English dictionary with handwritten notes in the margins.

The sender, a real estate developer named Marcus Webb, had almost discarded the entire trunk before his grandmother, a retired history teacher who had dedicated her life to preserving black heritage, insisted he contact the museum immediately.

“My grandmother said, “This photograph tells a story that needs to be heard,” Marcus had written in careful pemanship.

“She said, “Some secrets wait a hundred years to be told, and this one has waited long enough.

” Vanessa adjusted her magnifying glass and leaned closer to the image, her eyes scanning every detail.

The soldier’s posture was impeccable, his shoulders squared with military precision, his chin lifted with quiet dignity that seemed to radiate from the faded paper.

His uniform bore the distinctive insignia of the 3069th Infantry Regiment, the famed Harlem Hell Fighters, who had fought under French command when their own American army refused to let them see combat.

But it was the soldiers right hand that drew Vanessa’s attention most powerfully.

partially concealed against the dark fabric of his trousers, almost invisible unless you knew to look, he held something small, something metallic, something that caught the light of the photographers’s flash in a way that seemed almost deliberate, almost like a message waiting to be discovered.

She magnified the image further, her heart beginning to race with the familiar thrill of discovery.

The object was a metal, but not an American one.

The distinctive shape was unmistakable to anyone who studied military history.

A bronze cross suspended from a green and red ribbon.

A French Quadigare, one of France’s highest military honors for valor in combat.

The question that burned in Vanessa’s mind was simple but profound.

Why was this decorated hero hiding his medal in his hand instead of wearing it proudly on his chest where it belonged? The 30069th Infantry Regiment had entered the war as the 15th New York National Guard, a unit of black soldiers from Harlem who had volunteered to fight for a country that systematically denied them basic human rights.

Vanessa knew their story well.

It was one of the most remarkable and ultimately tragic chapters in American military history.

A tale of extraordinary courage met with shameful ingratitude.

These men had trained alongside white soldiers at Camp Wadssworth in South Carolina, where they faced constant harassment, racial slurs, and the everpresent threat of violence from both civilians and fellow servicemen.

They had been denied the right to march in New York’s farewell parade alongside white units because, as one white officer infamously declared with casual cruelty, “Black is not a color in the rainbow.

” When they finally arrived in France in December 1917, packed into the hold of a transport ship like cargo, they expected to enter combat immediately and prove their worth as soldiers.

Instead, the American Expeditionary Force assigned them to unload ships and build railroads, backbreaking labor duties that kept them far from the front lines and the glory of battle.

General John Persing, commander of American forces in Europe, refused to integrate black soldiers into white combat units.

And he had no intention of letting them fight as a separate American force where they might earn recognition and honors.

The message was brutally clear.

Black soldiers were good enough to work themselves to exhaustion, but not good enough to fight and die with honor.

The French army, desperate for reinforcements after years of devastating losses that had decimated an entire generation of young men, saw an opportunity.

They requested that the 369th be assigned to their command and Persing, eager to be rid of what he considered a troublesome problem, agreed without hesitation.

The French welcomed the Harlem soldiers with an openness and respect that shocked men who had grown accustomed to American racism from birth.

They trained together, ate together, fought together, bled together.

French officers addressed black soldiers as msure, and shook their hands without hesitation.

For the first time in their lives, these black Americans experienced something resembling genuine equality.

What followed was nothing short of extraordinary.

The 369th spent 191 consecutive days in combat, longer than any other American unit of its size during the entire war.

They never lost a single trench to the enemy.

They never had a single man captured.

They suffered overus 400 casualties, including more than 700 wounded in action, the highest casualty rate of any American regiment.

And when the war finally ended, France awarded the entire unit the Qua de Gare with 171 individual soldiers receiving personal decorations for exceptional valor.

They had earned a hero’s welcome, but they were returning to a nation that still considered them less than fully human.

Vanessa pulled up the regimental records on her computer, searching methodically for any soldier who matched the man in the photograph.

The face was distinctive.

A strong jaw that suggested determination.

Deep set eyes that seemed to hold secrets.

A small scar above the left eyebrow that suggested a wound survived.

Somewhere in those yellowed records, she was certain his story was waiting to be discovered.

And with it, perhaps an explanation for why a decorated hero would hide his medal on what should have been the proudest day of his entire life.

Three weeks of painstaking searching through military archives, regimental rosters, and digitized service records finally yielded a name.

Private First Class Thomas Jefferson Williams, born 1894 in Albany, Georgia, enlisted 1917 in New York City.

The military photograph attached to his service record matched the man in the portrait with unmistakable certainty.

The same strong jaw, the same deep set eyes that seemed to look through the camera into the future.

The same small scar above his left eyebrow now explained by a clinical notation in his medical file.

Shrapnel wound, left orbital region, news argon offensive, September 1918.

Prognosis: full recovery expected.

Vanessa’s hands trembled slightly as she scrolled through Thomas’ complete service record, each page revealing new details of a life lived with extraordinary courage.

He had been assigned to company C of the 369th Infantry Regiment, and had served with distinction throughout the regiment’s legendary 191 days of continuous combat.

His file contained commendations from French officers praising his remarkable bravery under fire, his skill as a rifleman that bordered on supernatural, and his calm leadership that inspired the men around him even in the most desperate circumstances.

On September 29th, 1918, during the brutal Muse Argon offensive, the deadliest battle in American military history, Thomas had single-handedly held a defensive position against a German assault while his wounded comrades retreated to safety.

For this extraordinary action, he had been awarded the Qua de Gare with Bronze Star, one of France’s highest military honors for valor in combat.

But the American military records told a starkly different story.

There was no mention whatsoever of Thomas’ French decoration.

No acknowledgement of his heroism in holding that position.

His discharge papers listed him simply as private first class, honorable discharge, February 1919.

or a rotor, the man who had held a position against impossible odds, who had been personally decorated by the French government in a formal ceremony, who had saved the lives of a dozen fellow soldiers, returned to America as just another anonymous black soldier without distinction.

His courage had been systematically erased by his own country, buried under layers of bureaucratic indifference and institutional racism.

Vanessa contacted the National Archives in Washington, requesting any additional documentation related to Thomas Williams that might have survived.

A week later, a package arrived containing photocopies of documents she had never expected to find.

A formal complaint filed by Thomas’ commanding officer, Captain Arthur Little, protesting the army’s systematic refusal to recommend black soldiers for American decorations.

And these men have fought with extraordinary valor under the most trying conditions.

Little had written in passionate frustration in December 1918, “They deserve recognition equal to their white counterparts, who have done no more and often less.

To deny them this honor is a moral failing of the highest order and a stain upon the conscience of this nation.

The complaint had been stamped, no action required, in red ink and filed away, buried in bureaucratic obscurity for over a century.

Vanessa stared at the faded document, feeling the weight of institutional racism pressing down across the decades like a physical force.

Thomas Williams had been a hero by any objective measure.

France had recognized him with one of their highest honors.

His own commanding officer had fought for him with passionate conviction.

and America had simply looked away, pretending he didn’t exist.

But why, she wondered with growing urgency, would Thomas hide his French medal in a photograph taken after the war in the safety of a Harlem studio? What was he so afraid of? February 17th, 1919.

Vanessa had read about this historic day countless times throughout her career, but researching it now felt different, more personal, more urgent.

On that cold Monday morning, beneath gray skies that threatened snow, nearly 3,000 soldiers of the 369th Infantry Regiment marched up Fifth Avenue in New York City, the first American combat unit to return from France.

Hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers, black and white alike, lined the streets for miles, cheering until their voices gave out, weeping openly, throwing flowers and confetti into the winter air.

The regiment’s legendary jazz band, led by the incomparable Lieutenant James Ree Europe, played triumphant music that seemed to shake the very buildings as the Hell Fighters marched in perfect formation.

Their French helmets gleaming in the pale winter light, their quadagare medals proudly displayed on their chests.

It was a moment of extraordinary triumph, but also of bitter irony that cut to the bone.

These men had spent 191 consecutive days fighting and dying for democracy in the muddy trenches of Europe, only to return to a nation where they could not vote in most states, could not eat in white restaurants, could not drink from white water fountains, could not sit in the front of buses or trains.

The parade ended at 145th Street in Harlem, where the soldiers were finally among their own people, finally able to celebrate without the watchful eyes of white America judging their every movement and expression.

Vanessa found newspaper accounts from that historic day, searching methodically for any mention of Thomas Williams.

She found him in an unexpected place, a small article buried in the back pages of the New York age, Harlem’s leading black newspaper.

Private Thomas Williams of Albany, Georgia, was among those decorated by France for exceptional bravery during the Muse Argon offensive.

The article noted in matterof fact pros Williams who single-handedly repelled a German assault while ensuring the safe retreat of wounded comrades plans to return to Georgia following his discharge to marry his sweetheart Miss LMA Johnson who traveled north by train to witness the historic parade Georgia.

The word struck Vanessa like a physical blow to the chest.

Thomas Williams wasn’t just returning to the south.

He was returning to one of the most dangerous states in America for a black man in 1919.

especially a black man who had tasted equality in France who had been honored by a foreign government who carried himself with the quiet pride of a decorated combat soldier.

In 1919, Georgia led the entire nation in lynchings with mobs murdering black citizens with impunity while local authorities looked away and a black man wearing a French medal walking with his head held high, refusing to step off the sidewalk for white pedestrians, speaking with the confidence of a man who had proven his worth on the battlefield.

Such a man would be seen as dangerous beyond measure.

Such a man would be seen as an existential threat to the established racial order.

Vanessa looked again at the photograph at Thomas’s hand carefully concealing the quad deare against his dark trousers.

The metal almost invisible unless you knew exactly where to look.

He wasn’t hiding his medal out of modesty or humility.

He was hiding it out of survival.

In the Jim Crow South, a decorated black hero was not a source of community pride.

He was a target marked for destruction.

And Thomas Williams knew it with the certainty of a man who had grown up under that brutal system.

The year 1919 became known to historians as the Red Summer, not for communist revolution, as some initially feared, but for the blood of black Americans spilled across the nation in an unprecedented wave of racial violence.

Vanessa immersed herself in the historical records of that terrible year.

Searching for any trace of Thomas Williams after the February parade, hoping to find evidence that he had survived the dangers waiting for him in Georgia.

What she found instead was a portrait of a nation descending into racial terror on a scale not seen since the darkest days following the Civil War.

Between April and November of 1919, race riots erupted in more than three dozen cities across America, from the industrial north to the rural south and everywhere between.

In Chicago, a black teenager named Eugene Williams, swimming in Lake Michigan on a sweltering July afternoon, accidentally drifted into waters claimed by whites and was stoned to death by a mob while police watched without intervening.

His murder sparked a week of uncontrolled violence that left 38 people dead, over 500 injured, and a thousand black families homeless after their houses were burned to the ground.

In Washington, DC, white mobs attacked black neighborhoods for four consecutive days, while police officers stood by or joined the attackers.

In Elaine, Arkansas, white vigilantes massacred an estimated 200 black sharecroppers.

Some historians believe the true number was far higher, who had committed the unforgivable sin of organizing for better wages.

And throughout the South, returning black veterans were specifically and systematically targeted for violence.

The message was brutally, unmistakably clear.

Black men who had fought for democracy abroad would not be permitted to claim it at home.

White newspapers published editorials warning of uppidity negroes who had been ruined by their time in France, where they had been treated as equals and had developed dangerous ideas about their own humanity.

The Ku Klux Clan, which had been largely dormant for decades, experienced a massive resurgence that would eventually swell its membership to over 4 million, recruiting new members who saw returning black veterans as an existential threat to white supremacy and the southern way of life.

In Georgia alone, more than 20 black men were lynched in 1919, and several of them were veterans who had made the fatal mistake of wearing their uniforms in public.

Vanessa found a chilling document buried in the NAACP archives.

A confidential report compiled by field investigators documenting specific incidents of violence against black veterans.

One entry dated July 1919 described an incident in rural Georgia that made her blood run cold.

A colored veteran of the 369th Regiment was severely beaten by a mob of approximately 15 white men after refusing to remove his military uniform while walking through town.

The veteran was rescued by a white store owner who hid him in his cellar until nightfall.

His current whereabouts are unknown.

The report did not name the veteran, but the location, a small town approximately 30 mi from Alb, Georgia, made Vanessa’s heart race with desperate hope.

Could this have been Thomas Williams? Had he survived the trenches of France, the mud and blood and poison gas, only to face violence in his own homeland? She needed to find out what had happened to him, but the official records had gone completely silent after his February discharge.

If Thomas’ story continued beyond that point, it would have to be found somewhere else.

In family memories carefully preserved across generations, in community archives maintained by black churches, in the oral histories that black Americans had learned to keep when official history systematically failed them.

Finding Thomas Williams descendants required patience, creativity, and a network of contacts that Vanessa had spent years cultivating throughout her career.

She reached out to genealological societies specializing in African-American lineages, historically black churches in Georgia and New York, online ancestry communities, and retired librarians who had dedicated their lives to preserving records that mainstream archives had neglected.

For weeks that stretched into months, she received nothing but dead ends and apologetic emails explaining that records from that era were fragmentaryary at best, especially for black families who had moved frequently to escape violence.

Then on a rainy Thursday afternoon when she had nearly abandoned hope, her office phone rang.

The caller identified herself as Dorothy Williams Carter, an 87year-old retired school teacher living in Atlanta.

Her voice was clear and strong despite her advanced age, carrying the measured cadence of someone accustomed to commanding attention in a classroom, someone who had spent decades teaching children to value their heritage.

“I understand you’re looking for information about my grandfather,” she said without preamble.

“Thomas Jefferson Williams, the soldier who hid his medal.

” Vanessa nearly dropped the phone, her hands suddenly trembling with excitement.

You know about the photograph.

I know about everything, Dorothy replied.

And Vanessa could hear the smile in her voice despite the weight of the words.

My grandmother, Ella, told me stories my whole life, from the time I was old enough to understand until the day she passed at 93 years old.

She made me promise to remember every detail, to pass them down to my own children and grandchildren, to wait for the day when someone would finally want to hear the truth.

She said that day would come eventually.

The truth has a way of rising, no matter how deep you bury it.

I’ve been waiting 70 years for this call.

Dr.

Brooks, 70 years.

Dorothy agreed to meet Vanessa in Atlanta the following week.

She lived in a modest brick house in a historically black neighborhood, its walls covered with family photographs spanning five generations of Williams descendants.

On the coffee table in her immaculate living room sat a wooden box, its surface worn smooth by decades of reverent handling.

Dorothy opened it with the care one reserves for sacred objects, revealing a collection of treasures that took Vanessa’s breath away.

Letters written in faded ink on paper so fragile it threatened to crumble.

A French English pocket dictionary with handwritten notes filling every margin.

A photograph of Thomas in his uniform standing with his French comrades.

A purple heart that had apparently never been officially recorded.

And a bronze medal on a green and red ribbon slightly tarnished but unmistakable.

The Qua Deare,” Vanessa whispered, reaching out to touch it with trembling fingers, hardly believing it was real.

“My grandfather earned this medal for saving 12 men during a German assault,” Dorothy said, her voice steady, but her eyes glistening.

The French called him a hero.

His commanding officer called him a hero.

The men whose lives he saved called him a hero every day until they died.

But when he came home to Georgia, he couldn’t wear it.

He couldn’t even speak about it except in whispers.

a black man who acted proud.

Who carried himself like he mattered, like he was as good as any white man.

That was enough to get you killed in those days.

So he hid his medal.

He hid his stories.

He hid his very self.

But he never stopped being a hero.

Not for one single day of his life.

And now finally, after all these years, the world is going to know his name.

A mur Dorothy’s wooden box contained far more than just the medal.

It held an entire hidden history carefully preserved across four generations of Williams women who had guarded these treasures with fierce devotion.

There were letters Thomas had written to Ella during the war describing the horrors of the trenches in vivid detail, but also the unexpected kindness of the French people who had welcomed him as a man rather than dismissing him as a negro.

There were official documents from the French military, including the formal citation for his cuadigar, written in elegant cursive script that praised his exceptional courage and complete disregard for personal safety in the face of overwhelming enemy forces.

There was a photograph of Thomas with his French comrades, arms around each other’s shoulders, smiling with the easy camaraderie of men who had faced death together and survived.

And there was a diary, small, leatherbound, its pages filled with Thomas’s careful handwriting that remained remarkably legible despite the passage of over a century.

Vanessa spent three full days in Dorothy’s living room, photographing each document with meticulous care, transcribing the diary entries, word by word, piecing together a story that had been deliberately silenced for a hundred years.

Thomas’s words transported her across time and space to the muddy, bloody trenches of the Western Front, where young black men from Harlem fought and died alongside French soldiers who treated them as equals and brothers for the first time in their American lives.

“The French do not look at us the way white Americans do,” Thomas had written in September 1918, just days before the action that would earn him the quadare.

“They see soldiers, not negroes.

They see men, not beasts of burden.

They share their food, their wine, their stories, their hopes and fears.

When a French officer speaks to me, he looks into my eyes, not over my head or through me as if I were invisible.

For the first time in my 24 years of life, I feel like a man, not a thing to be despised and discarded.

I fear what will happen when we return home.

I fear that the men we have become in France will not be permitted to exist in America.

I fear that everything we have earned with our blood will be taken from us the moment we step off the ship.

His fears proved tragically prophetic.

The diaryy’s final entries, written in February and March of 1919, described the suffocating return to Jim Crow reality and language that grew increasingly desperate.

Thomas and Ella had married in a small ceremony in a Harlem church, surrounded by family and fellow veterans, then traveled south to Georgia by train, sitting in the colored car, of course, where Thomas hoped to buy land with his military savings and build a life worthy of the man he had become in France.

But Georgia had not changed one iota while he was fighting in the trenches.

The same white men who had terrorized black communities before the war were now specifically targeting veterans, determined to crush any spirit of equality that military service might have instilled.

They called it putting negroes back in their place.

I keep my medal hidden, Thomas wrote on March 15th, 1919.

I do not speak of France or the war except in whispers to Ella at night.

I lower my eyes when white men pass on the street.

I step off the sidewalk into the mud.

I become invisible because visibility means death in this place.

But at night, when Ella sleeps beside me, I hold my medal and remember what it felt like to be a hero.

I remember what it felt like to be a man.

They can make me hide, but they cannot make me forget who I truly am.

The diary’s entries became sporadic after March 1919.

The handwriting increasingly agitated and cramped, the tone shifting from weary resignation to barely controlled fear.

Thomas had found work as a farm hand on a white-owned plantation outside Albany, the only employment available to a black man in rural Georgia, regardless of his military service or the medals he had earned in the trenches of France.

He and Ella lived in a small cabin at the edge of the property, far from the main house, in the eyes of the white family who owned the land.

Their dreams of land ownership, of building something permanent and dignified, were fading with each passing month as Thomas’ savings dwindled and opportunities remained closed.

Then came the entry dated July 12th, 1919.

The last entry Thomas would ever write in his diary.

They came for me today.

Three white men in a truck wearing hoods to hide their cowardly faces, carrying torches and rope.

Someone had told them about my medal, about France, about the stories I sometimes told other colored men at church when I thought no white ears were listening.

They said I had gotten above myself.

They said France had ruined me, had given me ideas above my station.

They said they would teach me what happens to negroes who forget their place.

They said they would make an example of me.

Vanessa’s hands shook violently as she read the words, her heart pounding against her ribs.

The entry continued in handwriting that grew more frantic, describing how Thomas had fled into the Georgia woods as darkness fell, how the men had chased him for hours through swamps and thicket, how he could hear their dogs baying in the distance, how he had finally been cornered near a creek bed with nowhere left to run and nothing but his bare hands to defend himself.

But then, something utterly unexpected.

A white man I did not know appeared from the darkness like an apparition.

He carried a shotgun and spoke with a northern accent that reminded me of the officers I had served under.

He told the hooded men to leave immediately.

Said there would be no killing on his land tonight or any night.

Said he would shoot the first man who took another step forward.

They argued, called him a lover and a traitor to his race.

But they were afraid of his gun and his steady hands.

When they finally drove away into the darkness, the stranger helped me to my feet.

He said his name was Robert, that he had fought in France with a colored unit, that he had seen what we did in the Argon Forest.

He said he owed his life to a colored soldier who had carried him three miles to safety after a German shell took his leg below the knee.

He said he would not stand by and watch brave men be murdered for nothing more than the color of their skin.

The diary ended there, mid-page, as if Thomas had been interrupted and never returned to finish the entry.

But Dorothy knew the rest of the story because Ella had told it to her mother who had told it to her, passing down the truth across generations like a sacred inheritance.

Robert had been a former army officer who had purchased farmland in Georgia with his family’s money, haunted by what he had witnessed during the war and determined to do something meaningful with whatever years remained to him.

He had given Thomas and Ellis safe passage north, hidden in a wagon beneath bales of cotton, traveling by night and hiding by day.

They had returned to Harlem in August 1919, where Thomas lived quietly for another 42 years, working as a janitor and handyman, never speaking publicly about his service, never wearing his medal outside their small apartment, but never forgetting, not for a single moment, who he truly was inside.

Vanessa published her findings in the spring of 2020 in a peer-reviewed article for the Journal of African-American History titled Hidden Valor, the Qua Deare, and the Systematic Silencing of Black Heroism in World War I.

The evidence she had assembled was overwhelming and irrefutable.

Military records proving Thomas Williams documented heroism, French citations formally recording his decoration, his commanding officers impassioned protest against discrimination, the diary that revealed the terror he faced upon returning home, and the physical medal itself preserved by his family for over a century.

The story was picked up by national media within days of publication, spreading across newspapers, television networks, and social media platforms.

The response was immediate and deeply emotional.

Descendants of the 369th Infantry Regiment reached out from across the country and around the world, sharing their own family stories of hidden medals, silenced heroism, and ancestors who had been systematically denied recognition by their own nation simply because of the color of their skin.

Historians called for a comprehensive review of all black veterans from World War I, seeking to identify others who had been overlooked for American decorations due to the institutional racism that had pervaded the military establishment.

Dorothy Williams Carter, now 88 years old, but still sharp and determined, was invited to Washington, DC for a ceremony at the National Museum of African-American History and Culture.

She brought her grandfather’s wooden box containing the quad deare that had been hidden for over a century, the diary that documented his courage and his terror, and the photograph of him with his French comrades, young men, black and white, who had faced death together and loved each other as brothers.

Standing before a crowd of journalists, historians, military officials, and descendants of the Harlem Hell Fighters gathered from across the nation, Dorothy finally fulfilled the promise she’d made to her grandmother, Ella, 70 years earlier on her deathbed.

“My grandfather, Thomas Jefferson Williams, was a hero,” Dorothy declared, her voice steady and strong despite the tears streaming freely down her weathered face.

“France knew it and honored him with their highest decoration for valor.

His commanding officer knew it and fought for him against an indifferent bureaucracy.

The 12 men whose lives he saved knew it and thanked him until their dying days.

But America refused to see it because of the color of his skin.

He spent his whole life hiding.

Hiding his medal, hiding his stories, hiding his pride, hiding his very identity as a hero.

Because this country would have killed him for the crime of standing tall.

Today, we stop hiding.

Today, after 100 years of silence, the world finally knows his name.

Today, Thomas Jefferson Williams takes his rightful place among the heroes of this nation.

The Quadigare was placed in a new permanent exhibit dedicated to the Harlem Hell Fighters.

Alongside Thomas’s diary, his letters, his French English dictionary, and the photograph that had started it all, the portrait of a soldier and his wife, a decorated hero holding his hidden medal, waiting a 100red years for someone to look closely enough to notice what was in his hand.

On November 11th, 2023, Veterans Day, the 105th anniversary of the armistice that ended the First World War, a ceremony was held at the Muse Argoni American Cemetery in France, where over 14,000 American soldiers rest beneath identical white marble crosses stretching to the horizon in perfect rows.

Among the dignitaries gathered under gray autumn skies was Dorothy Williams Carter, now 91 years old, accompanied by three generations of her family, who had traveled across an ocean to stand where their ancestor had once fought, bled, and earned the recognition his own country had so cruy denied him.

The French government had arranged the ceremony after learning of Vanessa’s research, determined to honor a man who had served under their flag with such distinction.

A representative of the Ministry of Defense, respplended in formal military attire, read aloud the original 1918 citation for Thomas’s Qua de Gair, words that had never been spoken publicly in all the years since they were first written.

For exceptional courage under fire during the Muse Argon offensive of September 1918, Private First Class Thomas Jefferson Williams single-handedly held a critical defensive position against a determined enemy assault while ensuring the safe withdrawal of 12 wounded comrades.

His actions reflect the highest traditions of military valor and bring lasting honor to his regiment, to the Allied nations he served, and to the cause of freedom for which so many gave their lives.

Dorothy, supported by her granddaughter and great-grandson, placed a wreath at the base of the memorial.

The green and red ribbon of her grandfather’s medal pinned proudly to her coat for all to see.

Behind her, the names of hundreds of Harlem Hell Fighters were etched in white stone.

Men who had died fighting for a country that refused to acknowledge their full humanity, buried forever in a foreign land that had welcomed them as heroes and brothers.

My grandfather came to France as a secondass citizen, denied basic rights in the land of his birth, Dorothy said, addressing the assembled crowd with a voice that carried across the silent cemetery.

He returned home as a decorated hero.

But America forced him to become invisible again because his heroism threatened the lie of white supremacy.

For a hundred years, his story was hidden like his medal carefully concealed in his hand in that photograph, waiting for someone to look closely enough to finally see.

But secrets have a way of surviving against all odds.

Truth has a way of rising no matter how deep you try to bury it.

And heroes have a way of being remembered no matter how hard the world tries to forget them.

She turned to face the endless rows of white crosses, her voice dropping to a whisper that nonetheless carried across the reverent silence.

You are remembered now, grandfather.

France remembers you.

America finally remembers you.

Your family has always remembered you.

And we will make certain the world never forgets what you sacrificed, what you survived, what you endured, and what you truly were.

a hero in every meaning of that sacred word who deserved so much better than the country he served.

As the ceremony ended and the autumn sun began to set over the French countryside, painting the white crosses in shades of gold and amber, Vanessa watched Dorothy’s great grandchildren playing among the graves.

Children who would grow up knowing their ancestors complete story.

Children who would carry his legacy proudly into a future he could never have imagined when he hid his metal in that Harlem photography studio so long ago.

Thomas Jefferson Williams had waited a hundred years to be fully recognized.

His patience, his perseverance, his quiet dignity in the face of monstrous injustice.

These were the true medals he had earned, more precious than any bronze cross on any ribbon.

And now, at last, standing in the French soil he had once defended with his life, his story was finally being told to a world ready to

News

This 1889 studio portrait looks elegant — until you notice what’s on the woman’s wrist

This 1889 studio portrait appears elegant until you notice what’s wrapped around the woman’s wrist. Dr.Sarah Bennett had spent 17…

At first, it looked like a photo of two sisters—but then historians noticed their hands

At first, it looked like a photo of two sisters, but then historians noticed their hands. The archive room of…

It was just a portrait of a mother — but her brooch hides a dark secret

It was just a portrait of a mother and her family, but look more closely at her brooch. The estate…

It was just a seemingly innocent wedding photo from 1920 — but pay attention to the groom’s hand

It was just a seemingly innocent wedding photo from 1920. But pay attention to the groom’s hand. The Maxwell estate…

This 1925 wedding photo has been restored — and what appeared in the mirror shocked historians

This 1925 wedding photo has been restored, and what appeared in the mirror shocked historians. The photograph arrived at the…

It was just a portrait of newlyweds — until you see what’s in the bride’s hand

It was just a portrait of newlyweds until you see what’s in the bride’s hand. The afternoon light filtered through…

End of content

No more pages to load