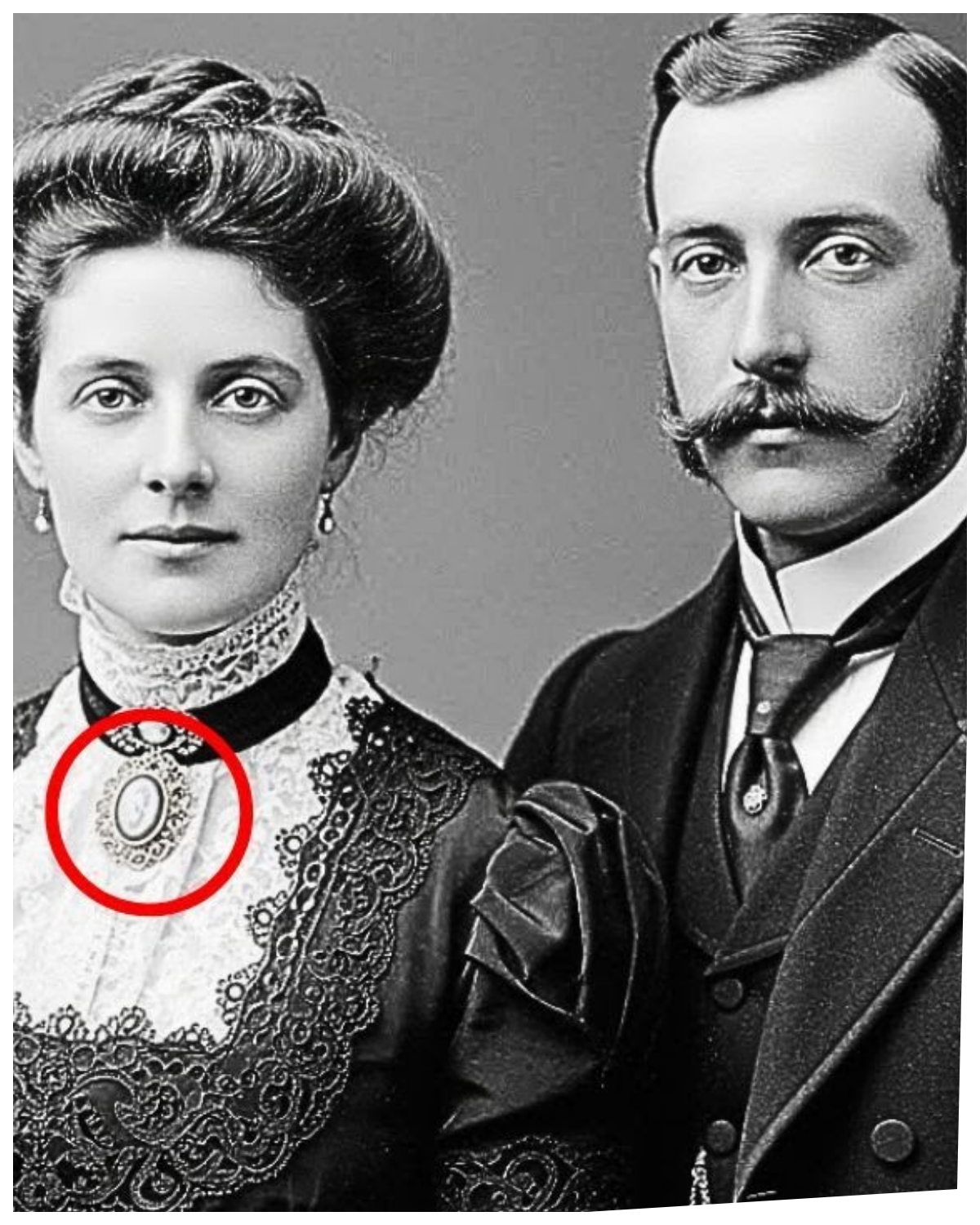

It was just a portrait of a mother and her family, but look more closely at her brooch.

The estate sale was winding down when Rachel noticed the photograph leaning against old furniture in a Providence, Rhode Island Victorian house.

She’d spent the morning documenting items for her antique photography business.

But this piece immediately caught her attention, not for its technical quality, but for the haunting quality it possessed.

The photograph showed a family portrait dated 198 on the photographers’s stamp.

Sterling and Sons Photography, Providence.

A young mother sat centered in the composition, flanked by her husband standing behind her and two servants positioned at the edges.

The formal Edwardian arrangement was typical of wealthy families during that period, but Rachel’s eyes kept returning to the mother.

She wore an elegant dark gown with lace detailing, her hair swept up in the Gibson girl style.

Her expression was what captured Rachel’s attention, eyes staring directly at the camera with profound sadness mixed with something resembling determination.

While the husband and servants maintained the typical stiff formality of the era, the woman’s face held genuine emotion.

Around her neck, prominently displayed against the dark fabric, was an ornate brooch.

Even in the photograph, Rachel could see it was substantial, probably 2 in across with gold filigree work surrounding a central oval element.

The way it was positioned suggested intentionality, as if the photographer had been directed to ensure it was clearly visible.

Rachel approached Dorothy, the estate sale coordinator.

How much for this photograph? $20.

The family’s from California selling everything.

Rachel paid and carried it carefully to her car.

Something about that woman’s expression and the prominent brooch compelled her attention.

Back in her studio, Rachel placed the photograph under her examination lamp.

She’d learned that old photographs often revealed hidden details under magnification.

She began scanning at high resolution, examining each element systematically.

The husband’s face was unremarkable, typical stern Victorian expression.

The servants were properly positioned at the background edges.

But when Rachel magnified the section containing the mother and her brooch, her breath caught.

What she had assumed was a decorative stone or enamel work in the brooch’s center was actually something else entirely.

Through the slightly clouded glass or crystal surface, she could see strands of hair carefully braided golden blonde arranged in an intricate pattern.

Rachel sat back, her heart racing.

This was morning jewelry, a Victorian tradition where locks of hair from deceased loved ones were preserved in brooches and lockets.

The hair was clearly from a young child.

fine, delicate, the color of sunshine.

She looked again at the mother’s face, seeing it now with new understanding.

That sadness wasn’t abstract.

It was the specific, devastating grief of a mother who had lost her child.

The family portrait wasn’t complete.

Someone was missing.

Who was this woman? What had happened to her child? And why did this photograph feel less like a simple family portrait and more like a mystery demanding answers? Rachel spent the evening researching Sterling and Sun’s photography.

The embossed stamp provided her starting point and she quickly located references to the studio in Providence city directories from the early 1900s.

Sterling and Sons had operated from 1895 to 1923 on Westminster Street.

The next morning she visited the Providence Public Library special collections.

Thomas, a librarian specializing in local history, helped her access the photography collection.

Sterling was one of the better portrait studios, Thomas explained, pulling archival boxes.

They catered to wealthy families, maintained meticulous records.

records.

Rachel’s interest sharpened, like client names.

Thomas checked his database.

We have a partial index from 1908, plus sample portraits they displayed in their shop window.

He pulled out a leatherbound album and turned pages chronologically through 1908.

Then he stopped.

Is this your photograph? Rachel stared.

It was the same image, the same family, the same woman with her prominent brooch beneath it in faded ink.

The Aldridge family, April 1908.

Aldridge,” Rachel whispered.

“Finally, a name.

” Thomas helped her access census records.

The 1910 census showed Katherine Aldridge, age 32, living on Benefit Street, one of Providence’s most prestigious addresses.

Her husband, Edward Aldridge, was a banker, a 45.

The household included three servants.

But what caught Rachel’s attention, no children listed.

She pulled 1900 census records.

Catherine appeared then as Katherine Brennan, aged 22, living in a southside tenement with her Irish immigrant parents.

Her father was a laborer.

Her mother took in laundry.

Catherine’s occupation mill worker.

The transformation was dramatic.

From workingclass Irish immigrant to banker’s wife on benefit street.

Catherine had crossed nearly impenetrable social boundaries.

Rachel searched birth records next.

She found it quickly.

Clara Katherine Aldridge, born December 3rd, 1902.

Mother Katherine Aldridge.

Father Edward Aldridge.

Then death records.

Clara’s death certificate, March 15th, 1907.

The child had been four years old.

Cause of death, fever, pneumonia.

Place of death, Providence City Hospital.

Rachel absorbed the timeline.

Clara died March 1907.

Catherine sat for this family portrait exactly one year later, April 1908, wearing her daughter’s hair in that prominent brooch.

This wasn’t just a memorial.

It was an anniversary portrait.

But something about the death certificate bothered Rachel.

Four-year-olds died of pneumonia frequently in that era.

Yet, Catherine’s expression, the way she displayed that brooch so prominently, it suggested something more complex than simple grief.

The family portrait showed a mother, father, and servants.

But the missing presence of the child felt deliberate, as if Catherine was making a statement about Clara’s absence.

Rachel needed to know more about what had happened at Providence City Hospital in March 1907.

There was a story here beyond a tragic death, and that brooch was the key to understanding it.

Providence City Hospital had been demolished in 1962, but its records were preserved by the Rhode Island Medical Society.

After two days navigating bureaucracy, Rachel gained access, accompanied by medical archivist Dr.

Patricia Hernandez.

“What are you looking for?” Patricia asked.

“Records for Clara Aldridge, who died here March 1907.

I’m trying to understand the circumstances.

” Patricia pulled up the digital index.

“CLatherine Aldridge, admitted March 12th, died March 15th, 1907.

” She paused.

There’s a note here about complaint documentation.

That’s unusual for records this old.

She retrieved an archival box containing Clara’s file.

The medical records were brief but troubling.

Clara had been brought to the hospital March 12th with high fever and difficulty breathing.

The admitting physician noted symptoms consistent with pneumonia, but treatment notes were sparse.

Minimal nursing care documented delays in examination.

Notations about the family’s inability to pay standard fees.

Then Rachel found the complaint filed three weeks after Claraara’s death, written in careful legal language and signed by Katherine Aldridge.

The complaint alleged Clara had been denied adequate care due to perceived inability to pay despite Edward Aldridge’s actual financial standing.

It claimed nursing staff ignored Catherine’s repeated requests for physician examination, that basic comfort measures were withheld, and by the time a senior doctor finally examined Clara on March 14th, her condition had deteriorated beyond effective treatment.

Most damning, Katherine alleged hospital intake staff had assumed based on Katherine’s Irish accent and manner of speaking that she was a charity case, a poor immigrant whose child didn’t warrant the same care as patients from established families.

By the time administrators realized Edward Aldridge was a prominent banker, Clara had already suffered two crucial days of neglect.

This is heartbreaking, Patricia said.

The hospital’s response is here, too.

The response was defensive.

Administrators acknowledged regrettable delays but attributed them to miscommunication and high patient volume.

They denied discriminatory practices, stating Clara’s death resulted from illness severity, not inadequate care.

Did Katherine pursue this further? Rachel asked.

Patricia searched broader records.

This is intriguing.

October 1907, 7 months after Clara’s death, the hospital implemented new patient intake procedures requiring standardized assessment regardless of perceived economic status.

The policy memo references recent events highlighting deficiencies in equitable care provision.

So Clara’s death changed something.

And look, December 1907, the hospital established a patient advocacy office funded by an anonymous donor.

The donation was substantial.

Rachel felt a chill.

Anonymous donor.

The financial records show anonymous via attorney, but the timing suggests a pattern.

Clara dies in March.

Catherine files her complaint in April.

Policy changes happened in October.

Advocacy office funded in December.

Rachel thought of the family portrait taken April 1908.

Catherine wearing her daughter’s hair prominently displayed, staring at the camera with grief and determination.

This wasn’t just mourning.

This was a woman who had fought back and was documenting her fight.

Rachel traced the attorney who’d filed Catherine’s complaint.

Crawford and Associates no longer existed, but she found its descendant firm, Baxter, Crawford and Morrison.

After explaining her research, managing partner James Morrison granted her access to historical files.

In the basement archive, they found the box labeled 1906 1908 client files ad.

Inside was a thick folder.

Aldridge Catherine hospital complaint.

The file contained not just the official complaint, but extensive correspondence between Catherine and attorney Samuel Crawford.

Rachel began reading, and Catherine’s voice emerged with startling clarity.

April 3rd, 1907.

Mr.

Crawford.

I’m writing at Mrs.

Elizabeth Porter’s recommendation.

My daughter Clara died 3 weeks ago at Providence City Hospital.

She was 4 years old.

I believe she died because hospital staff assumed I was a poor immigrant whose child didn’t deserve their attention.

By the time they realized my husband is Edward Aldridge of First Providence Bank, it was too late.

I know you may think I’m simply a grieving mother seeking blame.

But I kept careful notes of everything.

Times I asked for help and was ignored.

Which nurses refused to check on Clara.

which doctors never examined her despite my pleas.

I can prove they treated her differently than wealthy patients in private rooms.

My husband wants me to let this go.

He says pursuing complaints will bring scandal.

He doesn’t understand I must do this not just for Clara, but for all other children whose mothers speak with accents, who look like immigrants who don’t know how to demand proper care.

Please help me make Clara’s death mean something.

Samuel Crawford’s response was compassionate but realistic.

He warned that hospitals were formidable opponents with significant resources.

However, if her documentation was thorough, they had grounds for formal complaint and potentially civil action.

The correspondence continued through 1907.

Katherine’s notes were indeed thorough.

She’d recorded not just her experience, but had quietly interviewed other families, particularly immigrants, documenting a pattern of discriminatory treatment.

Samuel had used this evidence to build a broader case about systemic problems.

He’d presented findings to the hospital board, city health officials, and newspapers.

Rachel found July 1907 Providence Journal clippings.

Hospital accused of bias against immigrant families.

And banker’s wife reveals working-class roots in fight for medical justice.

The articles quoted Katherine directly, “My daughter died because they saw me as Irish immigrant Katherine Brennan, not Mrs.

Edward Aldridge.

Every mother deserves to have her child treated with the same care, regardless of her accent or origins.

” The publicity forced the hospital to implement policy changes.

But Rachel found something else.

A separate folder labeled anonymous donation December 1907.

Documents showed Katherine had arranged through Samuel Crawford to donate $10,000 to establish the patient advocacy office.

The donation was made anonymously to avoid appearing vindictive.

Catherine’s note to Samuel dated December 10th, 1907.

Policy changes are important, but policies can be ignored.

An advocacy office with dedicated staff, people whose job is helping families navigate care and speak up when they’re not heard.

That’s real and lasting.

Clara didn’t get an advocate.

Now other children will.

Rachel found one more document in Samuel Crawford’s files that illuminated everything.

A letter from Catherine dated March 1908, exactly one year after Clara’s death.

Dear Samuel, I wanted to inform you I’m having my family portrait photographed next month.

I will be wearing the morning brooch containing Clara’s hair.

Edward has asked me not to.

He says, displaying my grief so publicly is inappropriate, that it’s time to move forward.

But I need people to see it.

I need there to be a record that Clara existed, that she mattered, that her death changed something.

I know the portrait will seem strange, a family photograph with our daughter absent, yet her presence announced through the brooch I’m wearing.

But that’s exactly the point.

She should be there.

She would be there if the hospital had treated her properly.

Her absence is the statement I’m making.

Thank you for helping me fight for her.

We didn’t save Clara, but perhaps we’ve saved others.

Rachel looked at the date.

March 15th, 1908, exactly one year after Clara died.

Catherine had scheduled the portrait for the following month, deliberately timing it to mark that painful anniversary.

Now, Rachel understood the family portrait completely.

It wasn’t a typical wealthy family’s formal photograph.

It was Catherine’s public declaration.

The prominent display of the morning brooch, her direct gaze at the camera, the formal composition that emphasized Clara’s absence, all of it was intentional.

Edward stood behind Catherine, his hand not touching her shoulder, his expression carefully neutral.

He was present, but distanced, supporting her right to make this statement, even if he didn’t fully embrace it.

The servants flanked the edges, witnesses to this family’s grief and Catherine’s determination.

The photograph wasn’t about capturing happiness or family unity.

It was about making visible what the hospital’s negligence had taken away.

Every person who saw this portrait in Sterling and Son’s window display would see that brooch and know if they asked that it contained a dead child’s hair.

They would see the mother’s grief and the father’s stoic presence.

They would see a family broken by loss.

Catherine had used the most public medium available to her, a professional portrait displayed in a prominent studio window to ensure Clara wasn’t forgotten and that the injustice of her death remained visible.

Rachel needed to understand what happened to Catherine after this portrait was taken.

How had she lived with this grief? had her advocacy work continued and what had become of her relationship with Edward, who clearly hadn’t shared her need for public declaration? She returned to census records and city directories tracing Catherine’s life beyond 1908.

What she found suggested a woman who had channeled her grief into decades of quiet, determined action, and a marriage that had evolved into something more complex than traditional partnership.

Rachel discovered that after 1908, Catherine largely disappeared from Providence Society pages.

While Edward’s name appeared regularly at bank events and business dinners, Catherine was notably absent from the social functions expected of a banker’s wife.

Instead, Rachel found Catherine’s name in unexpected places.

At the Rhode Island Historical Society, she discovered records of the Brennan Family Services Center, which had operated in Fox Point from 1933 to 1954.

Catherine had founded and personally funded it, providing assistance to immigrant families, English language learning, navigation of legal and medical systems, job placement, emergency financial aid.

But Catherine’s advocacy work had started much earlier.

Rachel found her name on donor lists for settlement houses in the 1910s and meeting minutes for women’s suffrage organizations and in correspondence with labor reformers.

At Brown University’s special collections, Rachel found letters between Katherine and labor organizer Rose Cohen from 1912.

Dear Rose, I read about the strike at Riverside Mills with great concern.

I remember those conditions from my own time in the mills, and I know the courage it takes to stand up to owners.

Please let me know how I can help discreetly.

My position makes public involvement difficult, but I have resources to share.

Rose’s response indicated Katherine had been providing financial support to striking workers, paying for legal representation, and funding a food distribution center for strikers families, always anonymously, never seeking credit.

When Providence opened its first free health clinic for immigrant families in 1915, the founding donation came from an anonymous source.

Financial records showed it had been processed through Crawford and Associates.

Catherine’s donation, Samuel Crawford’s notes, confirmed it.

Mrs.

Aldridge wishes to establish a clinic ensuring no family faces the discrimination and delay that cost Clara her life.

She insists on anonymity.

She doesn’t want gratitude, only results.

Rachel also discovered Katherine’s testimony before a 1916 legislative committee arguing for child labor law reforms.

Gentlemen, I have stood where these children stand.

I worked in mills when I was 13, breathing cotton dust that damaged my lungs, working hours that left me exhausted and unable to attend school.

I escaped that life through marriage.

But most children aren’t so lucky.

They deserve the chance to be educated, to be healthy, to be children.

The reforms passed in 1917.

Catherine’s willingness to publicly acknowledge her working-class origins gave weight to arguments that middle-class reformers couldn’t match.

Rachel began seeing a pattern.

Every cause Katherine supported connected to her own experience.

Either her working-class childhood or Clara’s death.

She wasn’t interested in fashionable society charity.

She focused on systemic problems she’d experienced personally and understood how to address effectively.

The family portrait from 1908 suddenly made even more sense.

Catherine had used it to mark the moment she’d committed herself publicly to advocacy work.

The prominent brooch wasn’t just memorial jewelry.

It was a declaration of purpose, a visible reminder of why she would spend the next 48 years fighting for immigrant families and children.

Rachel needed to understand Edward’s perspective.

How had he responded to Catherine’s very public advocacy work that drew attention to her humble origins, something that must have been socially uncomfortable for a prominent banker.

She found clues in society pages and business news.

After Clara’s death and Catherine’s hospital complaint, Edward’s career had actually flourished.

By 1910, he was president of First Providence Bank.

His social standing seemed to have improved rather than suffered.

Rachel found an editorial from October 1907 that explained why.

It should be noted that Mr.

Edward Aldridge, while not directly involved in his wife’s campaign for hospital reform, has conducted himself with dignity throughout this difficult period.

His support of his wife’s right to advocate for change, even when it meant public revelation of her humble origins.

speaks to his character.

Providence’s business community should recognize that true gentlemen support their wives principled stands rather than silencing them for social convenience.

Edward hadn’t stopped Catherine’s advocacy, but had he actively supported her or simply tolerated it? Rachel found the answer in Edward’s 1932 obituary.

He died at 67, and the notice mentioned his establishment of the Clara Aldridge Memorial Fund in 1910, supporting medical care for indigent children in Providence.

The fund had operated until 1965.

Edward had created his own memorial to Clara, separate from Catherine’s advocacy, but clearly influenced by it.

He’d found his own way to honor their daughter’s memory.

Rachel discovered more through legal records.

Edward and Catherine had maintained separate bedrooms after 1908, and Edward spent increasing time at a club in Boston.

The marriage had become more partnership than romance, yet they never divorced, and Catherine inherited his substantial estate when he died.

Most illuminating was a letter Rachel found from Edward to his lawyer in 1920 discussing his will.

I want to ensure Catherine is provided for generously.

She has conducted herself with strength and principle throughout our marriage, particularly during the tragedy of losing Clara.

While we have grown apart in many ways, I have deep respect for her character.

She could have hidden her origins and lived comfortably in my world, but she chose to use her position to help others.

That required more courage than I possessed.

Edward had understood exactly what Catherine sacrificed.

her comfortable obscurity, her social acceptance to fight for other children.

He respected her for it, even if he couldn’t match her courage.

Their marriage had been complicated, shaped by class differences and grief.

But it endured because they found ways to honor each other despite their differences.

Edward gave Catherine freedom and resources to pursue justice.

Catherine gave Edward space to grieve in his own way.

The 1908 family portrait captured this dynamic perfectly.

Edward stood behind Catherine, but didn’t touch her.

Present, but distanced.

He supported her right to make her statement while maintaining his own emotional reserve.

The portrait showed a marriage that had evolved beyond traditional roles into something more complex and honest.

Rachel wanted to know what became of Catherine after Edward’s death in 1932.

Census records showed she’d remained on Benefit Street initially, but by 1950 had moved to a smaller house in Fox Point, a deliberate return to the working-class neighborhood where she’d grown up.

Catherine’s 1956 obituary was surprisingly detailed.

Katherine Brennan Aldridge, longtime Providence resident and advocate for immigrant families, died peacefully at her home on Iive Street on February 12th, 1956, age 78.

Born in Ireland in 1878, Mrs.

Aldridge immigrated to Providence with her parents as a child and worked in textile mills before marrying banker Edward Aldridge in 1902.

Mrs.

Aldridge became a prominent voice for medical equity after her daughter Clara’s death in 1907, leading efforts that resulted in significant reforms at Providence City Hospital following her husband’s death in 1932.

She dedicated herself to supporting immigrant families through the Brennan Family Services Center, which she founded and operated until her retirement in 1954.

Mrs.

Aldridge was known for her direct manner, her generosity to families in need, and her insistence that all people deserve dignity regardless of their origins.

At the Rhode Island Historical Society, Rachel found the Brennan Cent’s archived papers, thank you letters to Katherine, photographs of families she’d helped, records of hundreds of people who’d passed through the center over two decades.

One letter from 1948 particularly moved Rachel.

Dear Mrs.

Aldridge, my English is not so good, so my daughter helps me write this.

I want to thank you for helping my family when my husband was sick and we had no money for the doctor.

You said every mother should be able to get help for her children, and you made sure we could.

My daughter asks me why you help so many families.

I tell her what you told me that you had a daughter once who did not get the help she needed and now you make sure other children do get help.

Catherine had spent nearly 25 years helping families navigate the systems that had failed Clara.

Rachel found photographs of Catherine from these later years in contrast to the formal griefstricken woman in the 1908 portrait.

These images showed someone more comfortable, often surrounded by children and families smiling naturally.

In one photograph from 1950 taken at a community celebration, Catherine wore a simple dark dress with a single piece of jewelry visible at her collar.

Rachel enlarged the image and felt tears prick her eyes.

It was the same brooch, the morning jewelry containing Clara’s hair.

Even at 72, Catherine still wore her daughter’s memory close to her heart.

The historical society’s collection included a 1985 oral history interview with a woman who had been a teenager in the 1940s when her family received help from Katherine Center.

Mrs.

Aldridge was different from other rich ladies doing charity.

She didn’t make you feel small or ashamed.

She’d sit at the kitchen table with my mother, drinking tea, talking about how to handle the landlord or find a good doctor.

I asked her once about the brooch she always wore.

She told me it was her daughter’s hair, that her daughter had died very young.

She said wearing it reminded her why she did this work, why it mattered to help families when they needed it most.

Rachel still didn’t know how the family portrait had ended up in that estate sale.

She contacted Dorothy, who explained the house had belonged to the Sullivan family since the 1960s.

Investigating property records, Rachel discovered Catherine’s house on IV Street had been sold in 1957 to a couple named Sullivan.

The sale documentation noted furnishings and personal effects per agreement with a state executive.

Catherine’s executive had been Daniel Crawford, Samuel Crawford’s son.

Daniel had arranged for most belongings to be donated to charities, but some items, including personal photographs, were included with the house sale.

Rachel contacted Patricia Sullivan, granddaughter of the couple who’ bought the house.

Patricia remembered her grandmother mentioning items that had been there when they purchased it.

My grandmother said there were boxes of photographs in the attic that weren’t worth anything, but she kept them because she felt bad throwing away someone’s family pictures, Patricia explained.

Did your grandmother know who Katherine Aldridge was? Not really.

She knew the name from the deed, but that was it.

My grandmother was from Portugal, pretty new to Providence, and didn’t know local history.

So, the photograph sat in your attic for almost 60 years, I guess.

So, when my parents died and we had to sell, I hired Dorothy to handle everything.

I didn’t look through most of it carefully.

Rachel explained what she discovered about Catherine, and Patricia was quiet for a long moment.

So, that woman in the photograph, she helped families like mine, Portuguese immigrants.

Yes, her center helped immigrant families from many backgrounds.

Anyone who needed assistance.

And I almost threw away her photograph, Patricia said softly.

Over the following weeks, Rachel worked with Patricia to document the photograph’s providence.

Together, they researched the Sullivan family’s connection to Catherine’s work.

Patricia’s grandmother had, it turned out, visited the Brennan Family Services Center in 1952 when she first arrived in Providence, receiving help with English classes and job placement.

My grandmother never knew that the woman who’d owned her house was the same person who’d helped her when she first came to America, Patricia said.

She used to say someone had been kind to her when she needed it most, but she never knew their name.

It was Mrs.

Aldridge all along.

Rachel showed Patricia all the documents she’d found.

Catherine’s letters, the hospital complaint, the advocacy work, the photographs from Catherine’s later years.

Patricia looked at the 1908 family portrait with new understanding.

That brooch, she’s wearing her daughter’s hair, and she’s looking at the camera like she’s daring anyone to forget what happened.

Exactly, Rachel said.

This wasn’t just a family portrait.

It was Catherine’s declaration that she would spend the rest of her life making sure no other child died the way Clara did.

Patricia touched the photograph gently.

What are you going to do with all this information? Rachel had been thinking about that question for weeks.

She’d uncovered an extraordinary story of grief transformed into decades of advocacy, of a woman who’d used her privilege to help others rather than simply enjoying her comfortable life.

But how should that story be told? Rachel decided against sensationalizing Catherine’s story.

No dramatic headlines or social media campaigns.

Instead, she created a careful, respectful presentation of Katherine’s life, contextualizing it within the larger history of labor rights, immigrant experiences, and medical reform in early 20th century Providence.

She partnered with the Rhode Island Historical Society to create a small exhibit.

The centerpiece was the 1908 family portrait displayed alongside the actual morning brooch that Patricia had found in another box from the Sullivan House.

Catherine’s descendants had apparently stored it with other family items that eventually ended up in the attic.

The brooch was even more beautiful in person than in the photograph.

The gold filigree was intricate, delicate scrollwork surrounding the oval glass center.

Behind that glass, perfectly preserved after more than a century, was the braid of golden blonde hair.

Clara’s hair arranged in a Victorian pattern that looked like a tiny work of art.

Beside the portrait and brooch, the exhibit included Catherine’s letters, the hospital complaint, newspaper articles about her advocacy work, and photographs from her later years at the Brennan Family Services Center.

A timeline showed the direct connection between Clara’s death and the reforms that followed.

Policy changes at Providence City Hospital, establishment of the patient advocacy office, the free health clinic, child labor law reforms.

Most powerfully, the exhibit included testimonies from families Katherine had helped.

Maria’s letter from 1948 thanking her for medical assistance.

Rose Cohen’s correspondence about strike support, the oral history from the woman who’d known Katherine in the 1940s.

These voices showed the human impact of Katherine’s decades of work.

The exhibit opened quietly on a Tuesday morning.

No grand ceremony, just a small gathering of people connected to the story.

Patricia Sullivan was there with her extended family.

Representatives from organizations Catherine had supported attended.

A few elderly residents who vaguely remembered the Brennan Family Services Center came, curious about the woman who’d run it.

Rachel gave a brief talk about discovering the photograph and what her research had revealed.

She emphasized that Catherine had never sought recognition for her work, preferring to help families quietly and focus on results rather than credit.

But she left this photograph,” Rachel said, gesturing to the portrait.

She made sure that brooch was visible, that her grief was documented, that there was a record of why she did what she did.

I think she wanted the story told eventually, not for her own glory, but so others would know what one person could do when they chose courage over comfort.

After Rachel’s talk, people moved through the exhibit slowly, reading letters and examining documents.

Patricia stood before the portrait for a long time, studying Catherine’s face and the prominent brooch.

An elderly woman approached Rachel, introducing herself as Dr.

Dr.

Helen Martinez.

My mother was one of the first children treated at the free clinic Katherine helped establish in 1915.

She had pneumonia, the same illness that killed Clara.

But because of that clinic, my mother got proper care immediately.

She survived, raised a family, and lived to be 91.

I became a doctor because of my mother’s stories about how that clinic saved her life.

Rachel felt goosebumps.

Your mother’s life was saved because of what happened to Clara.

And because Katherine refused to let Clara’s death be meaningless, Dr.

Dr.

Martinez added, “That’s the legacy, isn’t it? One mother’s grief transformed into protection for thousands of other children.

” Over the following months, the exhibit drew modest but meaningful attention.

Local news covered it briefly.

Medical schools used it as a teaching example about the importance of equitable healthcare.

Immigrant advocacy organizations referenced Catherine’s work in their educational materials.

Rachel donated her complete research archive to the Rhode Island Historical Society, ensuring that future researchers could access Catherine’s story.

Patricia Sullivan donated the morning brooch to the exhibit permanently, feeling it belonged in a place where people could understand its significance.

The family portrait remained on display with a simple plaque.

Katherine Brennan Aldridge, 1878 1956.

In this 1908 portrait, taken one year after her daughter Clara’s death from hospital negligence.

Katherine wears a morning brooch containing Clara’s hair.

Her prominent display of this jewelry was a declaration that she would spend her life ensuring no other child suffered as Clara did.

Her advocacy led to hospital reforms, medical equity initiatives, and labor protections that helped thousands of immigrant families.

This photograph captures the moment she committed herself to transforming personal grief into systemic change.

Rachel returned to the exhibit often, studying the portrait with different eyes than when she’d first seen it at that estate sale.

She understood now what had compelled her attention.

The photograph contained not just grief, but purpose.

Catherine’s direct gaze at the camera wasn’t broken or defeated.

It was determined and strong.

The missing child in the family portrait was more present than many people who were actually photographed.

Clara’s absence was the statement.

Her hair preserved in that brooch and worn so prominently was the evidence.

And Catherine’s expression, that mixture of sadness and determination, was the promise that Clara’s death would mean something beyond loss.

Several months after the exhibit opened, Rachel received a letter from a woman in California named Helen, who’d seen a newspaper article about the exhibit.

Helen explained she was Catherine’s great great niece, descended from Catherine’s younger brother.

“Our family never talked about Catherine,” Helen wrote.

“We knew she’d caused some scandal in the 1890s, that she’d testified against her father or something like that.

” Wait, I’ve confused the story.

We were taught there was family shame around her, but we never knew details.

After reading about the exhibit, I realized we had it completely backward.

She’s the one family member we should be most proud of.

Helen visited Providence, and Rachel spent an afternoon showing her everything she’d discovered.

Helen wept when she saw the morning brooch and read Catherine’s letters.

She was so alone, Helen said quietly.

She did this enormous brave thing and then just lived quietly for decades, never seeking recognition.

But she wasn’t entirely alone, Rachel said, showing Helen the thank you letters from families.

She spent her life connected to the people she’d helped, even if they didn’t know all she’d done.

She had Samuel Crawford, who kept her secrets and supported her advocacy.

She had Edward, who gave her the freedom to live on her terms.

Maybe that was enough.

Helen nodded, studying the portrait.

She left this photograph so someone would eventually find it and understand.

You were meant to find it, Rachel.

Rachel didn’t believe in destiny, but she understood what Helen meant.

The photograph had survived decades in an attic, waiting for someone to look closely enough to see beyond the surface.

It had found its way to someone who cared about historical stories and knew how to research them properly.

And now, Catherine’s story was preserved and shared.

exactly as Catherine might have hoped.

As Rachel walked her studio that evening, she glanced at a copy of the portrait she’d kept on her wall.

Catherine stared back across more than a century, her daughter’s hair worn proudly at her throat, her expression still radiating that mixture of grief and determination.

It had been just a family portrait until Rachel noticed what the mother was wearing and asked why.

That question had opened up an entire hidden history of courage, loss, advocacy, and change.

Catherine had left that brooch visible.

That grief documented waiting for someone to care enough to look closely and ask what it meant.

And in that small act of attention across more than a hundred years, Catherine’s courage was finally recognized and honored.

Clara’s death had mattered.

Catherine’s life of advocacy had mattered.

And the photograph that captured both.

That moment when a grieving mother declared she would fight for other children continued to matter, inspiring new generations to transform their own grief into action, their own privilege into service.

The brooch with its lock of golden hair remained on display at the exhibit, a tiny memorial that had carried enormous meaning.

And beside it, the portrait showed Katherine wearing it with pride, her eyes meeting the camera with a gaze that said clearly, “Remember my daughter.

Remember what happened.

Remember why this work matters.

” The photograph wasn’t just history.

It was a call to action that still resonated.

A reminder that individual courage, properly documented and carefully preserved, could inspire change across generations.

Catherine had known that when she positioned herself for that portrait in April 1908, she’d understood the power of visible grief, of documented loss, of personal testimony transformed into public record.

It had been just a portrait of a mother until you realized her brooch was actually a lock of someone’s hair.

And that simple piece of jewelry held a story of love, loss, and decades of determined advocacy that changed countless lives.

News

It was just a seemingly innocent wedding photo from 1920 — but pay attention to the groom’s hand

It was just a seemingly innocent wedding photo from 1920. But pay attention to the groom’s hand. The Maxwell estate…

This 1925 wedding photo has been restored — and what appeared in the mirror shocked historians

This 1925 wedding photo has been restored, and what appeared in the mirror shocked historians. The photograph arrived at the…

It was just a portrait of newlyweds — until you see what’s in the bride’s hand

It was just a portrait of newlyweds until you see what’s in the bride’s hand. The afternoon light filtered through…

It was just a 1903 studio portrait — until you saw the strange symbols on the woman’s hand

It was just a 1903 studio portrait until you saw the strange symbols on the woman’s hand. Dr.Maya Richardson stood…

It Was Just a Photo of a Mother and Child — Until You Saw the Symbol Hidden in Her Fingers

It was just a photo of a mother and child until you saw the symbol hidden in her fingers. Dr.Maya…

No one ever noticed what was wrong with this 1930 family portrait — until it was restored

No one ever noticed what was wrong with this 1930 family portrait until it was restored. Jennifer Hayes carefully removed…

End of content

No more pages to load