Pope Leo I XIV Prepares to Reshape Catholic Worship as Vatican Debates Historic Liturgical Reform

The final light of a September afternoon streamed through the stained glass windows of Saint Peter’s Basilica, casting fractured colors across the face of Pope Leo I XIV as he studied the document before him.

The parchment, dense with carefully articulated provisions, carried consequences that would extend far beyond the walls of the Vatican.

His hand hovered above the page, steady yet burdened by the magnitude of what was to come.

This decision, he understood, would alter the daily worship of more than a billion Catholics and redefine how the Church expressed reverence in an age shaped by noise, speed, and distraction.

Within the papal library, silence reigned.

Towering shelves of ancient volumes rose toward the vaulted ceiling, their leather spines worn smooth by centuries of handling.

Manuscripts penned by theologians, popes, and scholars long deceased stood as mute witnesses to previous eras of reform and resistance.

The room carried the faint scent of incense mingled with old parchment, a reminder that every turning point in Church history had been accompanied by tension and prayer.

Cardinal Alberto Vincenzo entered with measured steps, his posture reflecting both respect for the papal office and unease born of the moment.

A veteran of Vatican diplomacy, his sharp features and pale eyes bore the mark of years spent negotiating delicate ecclesiastical and political matters across Europe and Asia.

He bowed deeply before the pontiff, then delivered his message with controlled urgency.

The council of cardinals had assembled in the adjacent chamber, and their anxiety was mounting as speculation spread regarding the proposed reforms to the Mass.

Concerns centered on the fear that the changes would disrupt liturgical patterns established after the Second Vatican Council.

Some cardinals believed the faithful, already navigating cultural upheaval and secular pressures, might struggle with reforms perceived as restrictive or unfamiliar.

Vincenzo spoke cautiously, choosing his words with the precision of a seasoned negotiator, while shifting his weight slightly, betraying his internal conflict.

Pope Leo lifted his gaze from the document.

At sixty-nine, the American-born pontiff carried himself with a calm authority shaped not by Vatican corridors alone, but by years spent far from Rome.

Formerly known as Robert Francis Prevost, he had grown up in Chicago before joining the Augustinian order, embracing a life of communal prayer, study, and service.

His dark eyes reflected a lifetime of endurance, marked by pastoral work in environments where faith was often the sole refuge against hardship.

He instructed the cardinal to inform the council that he would join them shortly, requesting a brief moment of solitude to reflect and pray.

Left alone once more, the pope allowed his thoughts to trace the path that had led him to this decisive hour.

His vocation had been forged not in academic halls alone, but in the demanding terrain of Peru’s Andean highlands and Amazonian lowlands.

As a young missionary, he had traversed muddy mountain trails and riverbanks to reach isolated villages.

He had celebrated Mass in makeshift chapels, ministered to communities devastated by floods and landslides, and witnessed how unadorned worship sustained hope amid suffering.

These experiences instilled in him a conviction that faith flourished most authentically when stripped of excess and centered on reverence.

His later service as bishop in northern Peru deepened that conviction.

There, he confronted social injustice, advocated for the poor, and navigated political instability, all while guiding communities whose devotion thrived without elaborate liturgical embellishments.

His subsequent appointment to a senior Vatican role overseeing episcopal affairs exposed him to the global machinery of the Church, granting him insight into how policy shaped parishes from Africa to Oceania.

Elected pope only months earlier, Leo had been perceived by many as a stabilizing figure following the energetic and reform-oriented papacy of his predecessor.

Yet those who cast their ballots had underestimated the depth of his resolve.

His vision of renewal was not driven by novelty, but by a desire to recover what he believed to be the Church’s spiritual core.

Rising from his desk, carved from dark walnut and adorned with subtle papal insignia, the pope approached the tall window overlooking Saint Peter’s Square.

Below, pilgrims filled the vast plaza, unaware of the transformation under consideration above them.

Families, elderly devotees, and young travelers moved freely beneath the fading sun, their lives soon to be touched by decisions made within the Apostolic Palace.

Leo’s fingers brushed the simple wooden pectoral cross resting against his cassock.

Carved from native Andean wood and gifted by villagers after a devastating flood, it served as a reminder of the Church’s mission to those on the margins.

The words that had guided his discernment echoed once more in his thoughts.

The Church existed not to affirm comfort, but to challenge complacency and bring solace to the afflicted.

The document before him bore the title Adoratio Veritas.

Its twelve provisions sought to reform the celebration of the Mass worldwide.

Drawing from scripture, early Church teachings, and the authentic intent of the Second Vatican Council, the text emphasized silence, reverence, and humility.

The pope had consulted widely, engaging theologians, liturgists, clergy, and lay Catholics from diverse cultures.

Their testimonies revealed a common hunger for depth amid a culture saturated with performance and distraction.

As the library door opened again, Cardinal Vincenzo returned, signaling that the council awaited.

Pope Leo folded the document carefully and placed it within his cassock.

With measured resolve, he proceeded toward the chamber where history awaited.

The council hall was adorned with frescoes depicting pivotal moments in Church history, reminders that renewal had always emerged from debate.

Twenty-five cardinals sat in solemn formation, their expressions reflecting anticipation, concern, and loyalty.

Silence fell as the pope entered.

Cardinal Jean Farah, a leading authority on liturgy, rose to voice objections.

He warned that extended periods of silence, restrictions on music, and the return of eastward orientation during the Eucharistic prayer could unsettle congregations accustomed to post-conciliar practices.

Others echoed concerns about alienating younger generations and diverse cultural expressions of worship.

Pope Leo listened without interruption, allowing debate to unfold fully.

When he finally spoke, his voice carried both gentleness and authority.

He affirmed that the reforms did not contradict the Second Vatican Council, but fulfilled its call for genuine participation.

True participation, he argued, was not constant activity, but interior engagement with the mystery of God.

Standing before a large crucifix, he spoke of a Church that had gradually adopted performative elements borrowed from secular culture.

Worship, he said, risked becoming spectacle rather than sacrifice.

Silence, reverence, and humility were not regressions, but pathways to deeper communion.

Support emerged from unexpected quarters.

Cardinal Takahashi of Tokyo described how contemplative liturgies had drawn young people in a frenetic urban environment seeking transcendence beyond constant stimulation.

The pope nodded in agreement, emphasizing that silence allowed God to speak amid modern chaos.

Debate intensified over the requirement to kneel and receive Communion on the tongue.

Leo defended the posture as an embodied expression of belief in the real presence of Christ, a gesture capable of forming reverence across generations.

News

🚨 FBI & ICE raid the fortress of a married Somali agent couple — 5 tons of drugs seized, secret empire exposed! 💣 as armored SUVs crash through the compound gates and federal agents swarm a luxury stronghold that insiders swear was untouchable until tonight, shattering reputations and igniting whispers of corruption so deep it might stretch from Minneapolis to power corridors nationwide 💊🏰 the narrator snarls that this wasn’t just a drug bust, it was the unraveling of a double life built on trust, treachery, and terror as the world watches the mighty fall 👇

The Fortress of Deceit: A Shocking Unraveling In the heart of a seemingly tranquil neighborhood, a fortress stood tall. This…

🚨 FBI & ICE raid Somali financial couple’s “fortress” in Minneapolis — tons of drugs seized as armored gates shudder, black‑suit agents swarm like lightning, and what looked like legitimate wealth turns out to be a clandestine empire built on secrets, pills, and predator deals 💊🏰 the narrator leans in with a smirk, teasing that this isn’t just a bust — it’s a betrayal so deep that neighbors whisper, insiders panic, and every ledger page screams corruption in the City of Lakes 👇

The Fortress of Deceit In the heart of Minneapolis, a couple lived in a mansion that seemed to touch the…

🚨 FBI & DHS raid Somali humanitarian couple’s “mega yacht” in CA—450 children rescued | FBI files as helicopters circle, waves crash, and a vessel meant for charity turns into the stage for the most shocking maritime bust of the decade 🚤💥 the narrator hisses that what seemed like goodwill hid a nightmare, where luxury met law, innocence met betrayal, and headlines barely scratch the surface 👇

Beneath the Surface: The Dark Secrets of a Humanitarian Facade In the early hours of dawn, the California coast lay…

🚨 3 min ago: FBI & DEA destroy Texas logistics “tunnel”—20 politicians down, 52 tons seized as sirens howl, concrete shatters, and a secret artery beneath the border is exposed in a raid so fast it left power brokers speechless and phones mysteriously silent 🕳️💥 the narrator bites that this wasn’t just a bust, it was a humiliation, where badges moved faster than leaks and the fallout climbed the food chain before sunrise 👇

The Collapse of Shadows: A Tale of Corruption and Redemption In the heart of Texas, where the sun blazed relentlessly…

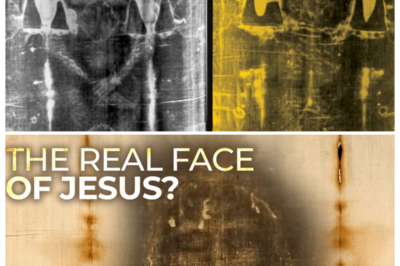

story’s most controversial relic ignites fresh obsession as ancient linen dares science, believers clash with skeptics, and every test result seems to raise louder questions than answers 📜🔥 the narrator leans in, teasing that this cloth doesn’t just survive scrutiny—it weaponizes it, turning labs into battlegrounds and faith into front-page drama 👇

The Veil of Secrets In the heart of Rome, a city steeped in history and mystery, a profound relic lay…

👀 “the face of God” Michael & the Shroud of Turin with Dr. Jeremiah Johnston explodes into a faith-rattling spectacle as an ancient face stares back through centuries, pixels tremble, and believers argue whether this is devotion, science, or a mirror no one was ready to face 📜🔥 the narrator leans in, teasing that when a face survives time itself, the real shock isn’t what you see—it’s what you can’t unsee 👇

The Revelation of Shadows In the heart of Rome, a city steeped in history, Dr.Jeremiah Johnston stood before the ancient…

End of content

No more pages to load