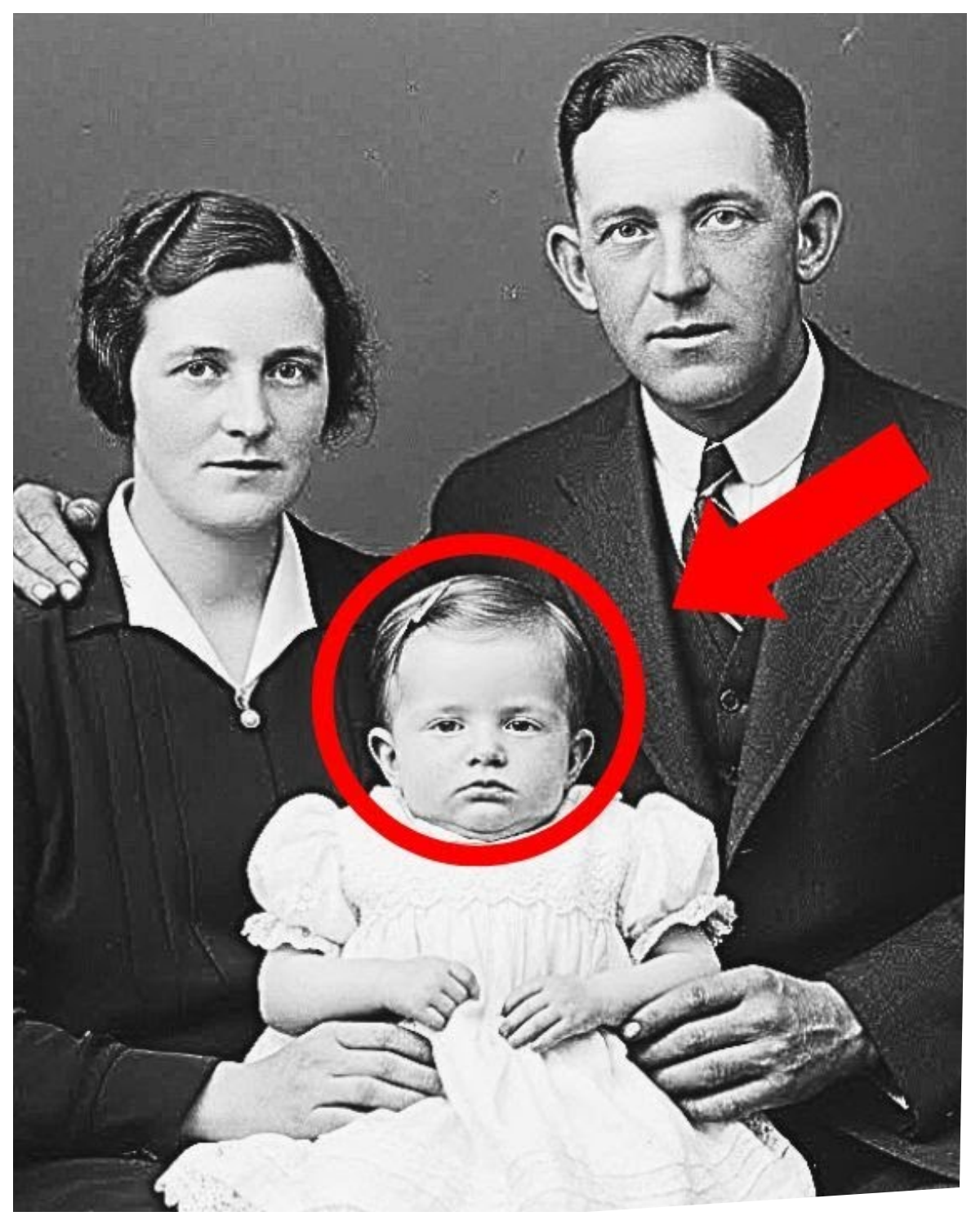

No one ever noticed what was wrong with this 1930 family portrait until it was restored.

Jennifer Hayes carefully removed the photograph from its deteriorated frame, her gloved hands steady despite 15 years of experience as a photo restoration specialist.

The image had arrived at her Chicago studio that morning, part of an estate donation destined for the local historical society.

The photograph was in poor condition, faded, stained with water damage with significant discoloration that obscured much of the detail.

The image showed a family of five, parents in their 30s, two boys who appeared to be around 8 and 10 years old, and a small girl perhaps three or four, seated on her mother’s lap.

They were dressed formally, positioned in what looked like a professional photography studio with the characteristic painted backdrop common to 1930.

On the back, written in faded ink, the Patterson family, Chicago, Illinois, March 1930.

Our precious ones.

Jennifer began the restoration process by scanning the photograph at high resolution, creating a digital file she could work with without risking further damage to the original.

As the image appeared on her computer screen, she started the painstaking work of digitally removing stains, adjusting contrast, and recovering details lost to time and deterioration.

She had restored hundreds of family photographs from this era, and she knew what to look for.

The formal poses, the serious expressions.

Smiling was uncommon in photographs that required long exposure times, the careful styling that showed families at their best.

But as she worked on cleaning up the image, adjusting the color balance, and removing the yellowing that had obscured the original tones, something began to trouble her.

The little girl on the mother’s lap looked different from the rest of the family in ways Jennifer couldn’t immediately articulate.

As she enhanced the clarity and adjusted the exposure, subtle details emerged that had been invisible in the damaged original.

The child’s complexion, even accounting for the sepia tone and age of the photograph, seemed unusual.

There was a faint blueg gray tinge around her lips and fingernails that became more apparent as Jennifer restored the images contrast.

Jennifer zoomed in on the child’s face.

The girl’s expression was placid, almost too still.

Her posture in her mother’s arm seemed carefully supported, as if she couldn’t sit upright on her own.

And there, just visible now that the water stains had been digitally removed, was a slight swelling around her ankles and wrists.

Jennifer sat back from her computer, a chill running down her spine.

She had seen these signs before in medical history books.

She needed to research further, but her instinct told her this photograph held a story far more poignant than a simple family portrait.

Jennifer spent her lunch break researching medical conditions that would produce the symptoms she was seeing in the restored photograph.

The bluish discoloration around the child’s lips and under her fingernails was called cyanosis, a sign that the blood wasn’t carrying enough oxygen.

In a photograph from 1930, before modern cardiac surgery, this almost certainly meant congenital heart disease.

She pulled up medical texts from the 1920s and 1930s, comparing clinical photographs of children with various cardiac conditions to the little girl in the Patterson family portrait.

The swelling she had noticed around the ankles, edema, combined with the cyanosis, suggested severe heart failure.

The child’s careful positioning in her mother’s arms now made more sense.

She likely couldn’t sit upright for long without becoming exhausted or short of breath.

Jennifer examined other details in the restored image.

The mother’s hands held the child with unmistakable tenderness, but also with the practiced care of someone who had spent months, perhaps years, supporting a fragile child.

The father’s hand rested on the mother’s shoulder, and his expression, now visible with the improved clarity, showed deep sadness beneath the formal composure expected for a portrait.

The two boys stood on either side of their parents, and Jennifer noticed they weren’t looking at the camera, but at their little sister.

Their expressions, too, carried an unusual gravity for children their age.

Jennifer pulled the historical society’s donation records to find more information about the Patterson family.

The photograph had come from the estate of a man named David Patterson, who had died at age 93.

The donation included several boxes of family papers, letters, and photographs spanning multiple generations.

She called the historical society’s archavist, Marcus Chen, and explained what she had discovered during the restoration.

I think this little girl was very sick when this photograph was taken, Jennifer said.

The medical signs are subtle in the original damaged image, but they’re clear once you restore the detail.

I’d like to examine the rest of the Patterson donation to learn more about this family.

Marcus was intrigued.

Come by this afternoon.

I’ll pull the boxes for you.

The Patterson family has an interesting history in Chicago.

The father was a factory foreman, solid working-class family during the depression.

I haven’t gone through all the materials yet, but there might be something about the daughter.

Jennifer saved her restoration work and prepared to visit the historical society, driven by a need to understand the story behind the photograph.

Something about the way the family had been posed, the timing of the portrait, and the visible signs of illness, suggested this wasn’t a routine family photograph.

It was something more deliberate, more precious, and possibly more heartbreaking.

Marcus had pulled three boxes of Patterson family materials and arranged them on a research table when Jennifer arrived at the historical society.

I did a quick preliminary search, he said, handing her a folder.

I found this obituary from 1930 that mentions a daughter.

Jennifer read the clipping from the Chicago Tribune dated April 1930.

Patterson Helen Rose Patterson, beloved daughter of Robert and Katherine Patterson, died April 12th, 1930 at age 3 years and 8 months.

Services will be held at St.

Michael’s Church.

In lie of flowers, donations may be made to Children’s Memorial Hospital Cardiac Research Fund.

Jennifer’s throat tightened.

The photograph was dated March 1930, just one month before Helen’s death.

The family had known they had taken the portrait knowing their daughter had weeks, perhaps days, left to live.

She began working through the first box, which contained family correspondents from the late 1920s and early 1930s.

In a bundle of letters tied with faded ribbon, she found correspondence between Katherine Patterson and her sister Elizabeth.

A letter dated January 1928 revealed Helen’s diagnosis.

Dearest Elizabeth, I’m writing with news that has shattered our world.

We took Helen to Children’s Memorial Hospital last week because she’s been so tired and breathless and her lips sometimes turn blue.

The doctors examined her thoroughly and told us she has a malf for her heart.

The chambers don’t work properly and her blood isn’t getting enough oxygen.

Elizabeth, they said there’s no treatment.

They said she might live a few months, maybe a year or two if we’re fortunate, but that her condition will progressively worsen.

Jennifer read on, her eyes filling with tears.

Robert held me while I cried for hours after the appointment.

How do we tell the boys that their little sister is dying? How do we watch her fade away knowing there is nothing we can do? The doctor said to keep her comfortable, avoid exertion, and cherish whatever time we have.

Time.

What a cruel word when you know it’s running out.

Letter after letter documented Helen’s decline over the next two years.

Catherine wrote about good days when Helen could play quietly with her dolls and bad days when she struggled to breathe and had to rest constantly.

She wrote about the boys learning to be gentle with their sister, understanding that she was fragile in ways other children weren’t.

A letter from December 1929 explained the family’s financial struggle.

The medical bills are overwhelming.

Robert works as much overtime as the factory will give him, but it’s never enough.

We’ve sold Catherine’s mother’s silver and some of our furniture.

The boys wear handme-downs and go without new shoes.

But we would give everything we own for more time with Helen.

Jennifer found the letter that explained why the Patterson family had commissioned the formal portrait in March 1930.

Catherine had written to Elizabeth February 1930.

Elizabeth, Dr.

Morrison, examined Helen yesterday and was grave.

The swelling in her legs and feet has worsened significantly.

Her heart is failing and he estimates she has perhaps 6 to 8 weeks remaining.

Robert and I discussed what we should do with the time we have left.

We want to create a memory, something tangible to hold on to when she is gone.

We have decided to have a family portrait made.

It will cost $5, money we can barely afford.

But what is money compared to having a photograph of all of us together while Helen is still with us? We want the boys to have this image to remember their sister not as she will be at the end struggling for every breath but as she is now our sweet girl surrounded by her family who loves her.

The letter continued with heartbreaking detail.

We will have to position Helen carefully in the portrait.

She can no longer sit upright on her own, so I will hold her in my lap supporting her weight.

We will dress her in her best dress, the white one with the lace collar that she loves.

Robert will stand behind us, strong and steady as he has been through this terrible trial.

The boys will stand beside us.

Our family complete one last time.

Jennifer found the photographers’s invoice tucked into the letters.

A receipt from Morrison Photography Studio dated March 15th, 1930 for one family portrait, $5.

Attached to it was a note in different handwriting.

Mrs.

Patterson, I made several extra prints of your family portrait at no additional charge.

I understand how precious this image is to you, and I wanted to ensure you have copies to share with family and to preserve.

Your daughter is a beautiful child, and it was an honor to photograph your family.

Harold Morrison, photographer.

A letter from Catherine to Elizabeth, dated March 20th, 1930, described the photography session.

We went to Mr.

Morrison’s studio last Saturday.

I was worried that Helen wouldn’t have the strength to endure the sitting, but she was having a good day, as good as her days are now.

We dressed her carefully, and I held her in my lap while Mr.

Morrison arranged us.

He was very patient, taking his time to ensure we were positioned comfortably.

Helen looked at the camera with those beautiful blue eyes, and for a moment, she seemed almost healthy.

The boys stood so straight and proud, wanting to look their best for their sister’s portrait.

Robert’s hand on my shoulder was the only thing keeping me from breaking down.

We all knew what this photograph represented.

The last time we would all be together, captured forever in silver and paper.

Jennifer continued reading Catherine’s letters to Elizabeth, documenting Helen’s last weeks of life.

The entries were increasingly fragmented as Catherine struggled to maintain daily life while caring for her dying daughter.

March 25th, 1930.

Helen is declining rapidly now.

She sleeps most of the day, waking only for brief periods.

Her breathing is labored and the blue color around her lips is constant now, not just when she’s tired.

Doctor Morrison visits every few days, though there’s nothing more he can do except prescribe morphine for her comfort.

Robert sits with her every evening after work, reading her favorite stories, even though she’s often too weak to respond.

April 1st, 1930.

The boys asked me today if Helen is going to heaven soon.

I couldn’t lie to them.

I told them yes, that her heart is too tired to keep working and that soon she will go to be with God where she won’t hurt anymore.

Thomas, our eldest, nodded and said, “I’ll take care of you and David when she’s gone, Papa.

” He’s only 10 years old, but this experience has aged him beyond his years.

April 5th, 1930.

Mr.

Morrison delivered the photographs today.

And when I saw the portrait, I broke down crying.

Not from sadness, though there is plenty of that, but from gratitude.

He captured us perfectly.

Helen looks peaceful in my arms.

The boys look strong.

And Robert and I look like what we are.

parents holding our family together in the face of unbearable loss.

This photograph is a gift, proof that Helen lived, that she was loved, that our family was whole, even if only for a brief time.

Jennifer found a diary that Catherine had kept during Helen’s final days.

The entries were brief but devastating.

April 10th, 1930.

Helen is struggling to breathe now.

We have moved her bed into our room so we can be near her constantly.

The boys come in before school and after to kiss her forehead and tell her they love her.

She can barely respond, but I know she hears them.

I know she feels how much she is loved.

April 11th, 1930.

Dr.

Morrison came this evening and said it won’t be much longer.

Helen’s heart is giving out.

Her hands and feet are cold and her breathing is shallow.

Robert and I are taking turns holding her, singing to her, telling her it’s okay to let go, that we will be all right, even though we won’t be.

How do you give your child permission to die? The final entry was dated April 12th, 1930.

Helen died at 3:20 this morning.

She was in my arms with Robert’s hand on her head and the boys sleeping in chairs beside the bed.

Her breathing simply stopped quietly and peacefully.

She had fought so hard for 3 years and 8 months and finally her tired heart could fight no more.

Our precious girl is gone.

Jennifer found newspaper clippings and funeral materials that documented the community’s response to Helen’s death.

The obituary in the Chicago Tribune was brief, but noted that Helen had been a courageous child who faced illness with remarkable grace.

The funeral program from St.

Michael’s Church listed hymns chosen specifically for a child’s service.

But it was the letters of condolence that revealed how Helen’s illness and death had affected not just her immediate family, but their entire community.

Jennifer found dozens of letters sent to Robert and Catherine in the weeks after Helen’s death.

From Mrs.

Adelaide Porter, a neighbor.

Dear Catherine and Robert, our hearts are broken for you and your boys.

Little Helen was a light in our neighborhood, always smiling, even when we could see she was struggling.

She taught us all about courage and grace in the face of suffering.

Please know that we are here for you in any way you need.

From Robert’s supervisor at the factory, Mr.

Patterson, please accept my deepest condolences on the loss of your daughter.

I know you worked every hour of overtime available to pay for her medical care and your dedication as a father was an inspiration to all of us.

Take whatever time you need before returning to work.

Catherine’s response to these letters preserved in her sister’s collection showed a mother struggling to process her grief.

May 1930.

Elizabeth, people keep telling me that Helen is in a better place, that she’s no longer suffering, that I should find comfort in knowing she’s at peace.

And perhaps they’re right.

But she’s not here.

She’s not in my arms.

I can’t sing to her or read her stories or watch her sleep.

The house feels empty without her labored breathing, without the constant vigilance we maintained for 3 years.

I don’t know how to live in this silence.

Robert’s letters to his brother painted a picture of a man trying to hold his family together while drowning in grief.

June 1930.

The boys are struggling.

Thomas has nightmares about Helen dying.

David, who is only eight, keeps asking when she’s coming back, as if death is something temporary.

And I don’t know how to help them because I can barely function myself.

I go to work, come home, sit in Helen’s empty room, and try to understand how the world can keep turning when our daughter is gone.

But Jennifer also found evidence of how the family had honored Helen’s memory.

A letter from Catherine dated July 1930 mentioned a donation.

Robert and I took the money we had been saving for Helen’s medical care about $30 that we never had to spend because she died before we could use it.

And we donated it to Children’s Memorial Hospital for cardiac research.

The doctor said that perhaps someday they will be able to repair hearts like Helen’s to save children who would have died like she did.

If our contribution helps even one child survive, then Helen’s suffering will have meant something.

Jennifer found a letter from Catherine to Elizabeth dated August 1930 that explained how important the March portrait had become to the family.

The photograph Mr.

Morrison made is displayed in our parlor now in a beautiful frame that Robert commissioned from a local craftsman.

Every day I look at that image and I remember Helen as she was that day dressed beautifully, held safely in my arms, surrounded by her father and brothers.

The photograph doesn’t show her struggling to breathe or the blue tinge to her skin or how weak she had become.

It shows our family whole and together exactly as I want to remember us.

The boys look at the photograph every morning before school.

Thomas told me last week that he talks to Helen in the picture, telling her about his day, about what he’s learning, about how much he misses her.

Is that strange? I don’t think so.

The photograph makes her present in a way that memories alone cannot.

She exists there, frozen in that moment.

Eternally 3 years old, eternally our little girl.

Jennifer discovered that the photograph had played a significant role in how the family processed their grief.

A letter from Robert to his brother in September 1930.

My brother asked me yesterday why we keep Helen’s portrait so prominently displayed.

Why we don’t put it away where it won’t cause us pain every time we see it.

But he doesn’t understand the photograph doesn’t cause pain.

It provides comfort.

When I look at that image, I don’t just see Helen dying.

I see her living.

I see the family we were, the love we shared, the precious time we had together.

however brief it was.

Catherine’s diary from November 1930 revealed another dimension of the photograph’s importance.

I realize today that the portrait Mr.

Morrison made will outlive all of us.

Long after Robert and I are gone, long after the boys have grown old and passed away, that photograph will remain.

Future generations of our family, great grandchildren and great great grandchildren we will never meet, will see Helen’s face and know that she existed, that she was loved, that she mattered.

The photograph is not just a memory for us.

It is Helen’s legacy, proof that her brief life had meaning and value.

Jennifer found evidence that the family had shared copies of the photograph with extended family members.

Letters from Catherine’s mother and Robert’s siblings mentioned receiving prints and how moved they were to have this image of Helen.

But perhaps most significantly, Jennifer discovered a letter from the photographer, Harold Morrison, to Catherine, dated December 1930.

Dear Mrs.

Patterson, I wanted to write to you about the portrait I made of your family last March.

In my 30 years as a photographer, I’ve made thousands of portraits, but few have affected me as deeply as yours.

When you came to my studio, I could see immediately that your daughter was gravely ill.

I understood what that photograph meant to you.

Not just a portrait, but a farewell, a preservation of love in the face of inevitable loss.

Jennifer completed the restoration of the Patterson family portrait, and the difference between the damaged original and the restored image was striking.

Details that had been obscured for 90 years were now clearly visible, including the subtle but unmistakable signs of Helen’s heart condition that the family had tried to minimize through careful positioning in the photographers’s skill.

She prepared a presentation for the historical society’s board, documenting not just the restoration process, but the story she had uncovered through the Patterson family papers.

When she showed the before and after images and explained the medical signs now visible in the restored photograph, the room fell silent.

This family knew their daughter was dying, Jennifer explained, pointing to the bluish discoloration around Helen’s lips, now clearly visible in the enhanced image.

They commissioned this portrait in March 1930, knowing she had weeks to live.

The photographer did everything he could to make Helen look healthy.

Careful lighting, positioning, retouching, but the signs of her condition are there if you know what to look for.

Modern restoration technology has revealed what the family and photographer tried to hide.

How sick this child really was.

The Historical Society’s director, Dr.

Patricia Williams was moved by the discovery.

This isn’t just a restored photograph, she said.

It’s a window into how families dealt with childhood illness and death during the depression.

The Pattersons couldn’t afford advanced medical care.

Not that it existed in 1930 for congenital heart defects anyway.

All they could do was love their daughter and preserve her memory through this portrait.

Dr.

Williams proposed creating an exhibition around the Patterson family story using the restored photograph as the centerpiece.

We could explore several themes, she suggested from the history of pediatric cardiac care, how families coped with childhood illness in the pre-annibotic era, the role of photography in preserving memory and processing grief, and the ethics of medical photography, when do we reveal painful truths, and when do we allow families to preserve the illusions they created, Jennifer agreed to curate the exhibition, working with medical historians and grief counselors to ensure the presentation was both historically accurate and emotionally sensitive.

Over the next three months, she collaborated with researchers to create a comprehensive display.

The exhibition included the original damaged photograph alongside the restored version with detailed annotations explaining what the restoration revealed.

Medical texts from the 1930s described the limited understanding of congenital heart disease at that time.

Letters from Katherine’s correspondents showed the family’s emotional journey through Helen’s illness and death.

But the exhibition also included modern context.

Jennifer worked with pediatric cardiologists from Children’s Memorial Hospital to create a display showing how the conditions that killed Helen in 1930, likely detrime or similar defect were now routinely corrected with surgery, allowing children to live full healthy lives.

The local newspaper ran a feature story about the exhibition before it opened, and the response was overwhelming.

The newspaper article about the Patterson family photograph caught the attention of someone Jennifer hadn’t expected to hear from.

Helen’s nephew, the son of Thomas Patterson, now 85 years old and living in a Chicago suburb.

Michael Patterson called the historical society the day after the article was published.

“That’s my aunt in that photograph,” he told the receptionist.

“My father was the older boy standing beside his parents.

He died 5 years ago, but he talked about Helen his entire life.

I need to see this exhibition.

” Jennifer met Michael Patterson at the historical society 2 days before the public opening.

He was a tall, dignified man who walked with a cane, and he carried a small box with him.

When Jennifer showed him the restored photograph, he stood silently in front of it for several minutes, tears streaming down his face.

“My father never got over losing her,” Michael said finally.

“He was 10 years old when she died, and he carried that grief for 83 years.

” He told me that Helen was the sweetest child, that even when she was sick and struggling to breathe, she would smile at him and his brother.

He said watching her die taught him that life was precious and fragile, and it shaped everything about how he lived his life afterward.

Michael opened the box he had brought.

Inside was another print of the same photograph.

This one in better condition than the historical society’s copy because it had been carefully preserved in a family album.

“My father kept this his entire life,” Michael explained.

“It hung in his bedroom until the day he died.

He would look at it every morning and every night, remembering his little sister.

” But Michael had brought something else as well.

A letter his father had written shortly before his death in 2018 addressed to whoever preserves our family’s history.

My name is Thomas Patterson.

I’m the older boy in the 1930 family photograph.

I’m writing this at age 88 and I want to tell you about my sister Helen who died when she was 3 years old and I was 10.

She had a bad heart and there was nothing the doctors could do to save her.

We knew for 2 years that she was dying and we watched her get weaker and sicker until finally her heart stopped.

The photograph you see was taken about a month before she died.

My parents wanted a picture of our whole family while Helen was still with us.

I remember that day.

We got dressed up in our best clothes and we went to the photography studio downtown.

Helen was so weak that mama had to hold her the whole time.

The photographer was very patient and he took several pictures to make sure we had a good one.

I want you to know that Helen was more than a sick child.

She was funny and sweet.

She loved having us read to her.

She loved her dolls.

She loved it when Papa would carry her outside to see the flowers.

The exhibition opened to the public on a Saturday morning in October, and the turnout exceeded everyone’s expectations.

Families came to see the Patterson portrait to read Catherine’s letters to understand how one family had navigated unimaginable loss during an era when childhood death was far more common than today.

Jennifer stood near the restored photograph, watching visitors reactions.

Many cried.

Parents held their children closer.

Medical students studied the visible signs of Helen’s cardiac condition with both clinical interest and deep empathy.

Michael Patterson attended the opening with his own children and grandchildren.

Helen’s great nieces and great nephews who had never known her, but who were moved by her story.

“She’s part of our family history,” Michael’s daughter said, looking at the photograph.

“We tell our children about great aunt Helen, about how she fought to live even though her heart was broken, about how much she was loved.

” The exhibition included a modern component that Jennifer had insisted on, a partnership with Children’s Memorial Hospital to provide information about congenital heart defects, their treatment, and resources for families dealing with pediatric cardiac conditions.

A hospital representative, was present at the opening to answer questions and provide support.

Dr.

Rachel Morrison, a pediatric cardiologist, no relation to the photographer, gave a brief presentation about how far cardiac medicine had advanced since 1930.

The condition that killed Helen Patterson would likely be diagnosed during pregnancy today.

She explained if a baby is born with tetrology of fallout or a similar defect we can perform corrective surgery in infancy.

The survival rate is over 95%.

Children who would have died like Helen now grow up to live completely normal lives.

She paused looking at the photograph.

But we can’t forget that for most of human history families like the Pattersons had no options.

They could only love their children and watch them die.

This photograph is a testament to that love and to the importance of continuing to advance medical care so that no family has to face what the Pattersons faced.

A reporter from the Chicago Tribune interviewed Jennifer about the restoration process and what it had revealed.

When I first saw this photograph, it was damaged and faded.

Jennifer explained, “The medical signs of Helen’s condition were barely visible, but as I restored the image, removing stains and enhancing detail, those signs became clear.

The blue tinge around her lips, the swelling in her hands, the careful way her mother held her.

All of it told a story that the family had tried to soften but couldn’t completely hide.

“What makes this photograph so powerful,” Jennifer continued, “is that it represents a moment of love and dignity in the face of inevitable loss.

The Pattersons knew Helen was dying.

They could have withdrawn from the world, hidden their grief in their sick child.

Instead, they chose to document their family, to claim Helen’s place in their history, to say, “She was here, she mattered, and we loved her.

” That’s why this photograph survived for 90 years, and why it continues to move people today.

The exhibition ran for 6 months and was visited by over 15,000 people.

It generated discussions about medical ethics, the history of pediatric care, and how families process grief and loss.

Several medical schools requested permission to use the Patterson photograph and materials in their curricula, teaching future doctors about the human dimension of medical conditions and the importance of supporting families through impossible situations.

For Jennifer, the restoration of the Patterson family portrait had become the most meaningful project of her career.

She had uncovered not just the technical details hidden in a damaged photograph, but a profound human story about love, loss, and the lengths families go to preserve memory.

That evening, after the exhibition opening, Jennifer returned to her studio and wrote a final entry in her project journal.

The Patterson family portrait from March 1930 appeared to be a simple damaged photograph when it arrived for restoration.

But as I removed years of deterioration and enhanced details that had been invisible for nine decades, I discovered that it documented a family’s farewell to their dying daughter.

Helen Patterson, age three, had a severe congenital heart defect.

Her parents knew she had weeks to live when they commissioned this portrait.

They wanted one photograph of their complete family before death separated them.

The restoration revealed medical signs that the family and photographer had tried to minimize.

Cyanosis, edema, physical frailty, but also revealed something more important.

The profound love of parents holding their child one last time.

A brother standing protectively near their little sister, of a family refusing to let illness define their final memory together.

This photograph survived because it mattered.

The Pattersons preserved it, shared it with family, and passed it down through generations as proof that Helen lived, that she was loved, and that her brief life had meaning.

The restoration didn’t just recover an image.

It recovered a story that deserves to be remembered and honored.

She closed the journal and looked at the restored photograph on her screen one last time.

Helen’s face, now clear and detailed after 90 years of obscurity, seemed to look back at her with quiet dignity.

A child who had died before modern medicine could save her, preserved forever in her family’s love.

Her story finally told to a world that had forgotten how recently childhood death was common and inevitable.

Jennifer saved the file and turned off her computer, knowing that the Patterson family portrait would continue to speak to future generations, not just about loss, but about love, memory, and the enduring power of a single photograph to preserve what matters Boost.

News

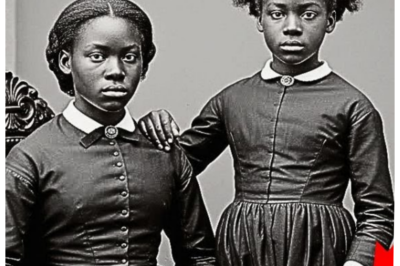

Why were Experts Turn Pale When They enlarged This Portrait of Two Friends from 1888?

Why did experts turn pale when they zoomed into this portrait of two friends from 1888? The digital archive room…

It was just a portrait of two sisters — and experts pale when they notice the younger sister’s hand

It was just a portrait of two sisters, and experts pale when they noticed the younger sister’s hand. The photograph…

🌲 VANISHED IN MONTANA — THREE YEARS LATER HIS BODY EMERGES WRAPPED INSIDE A DEAD TREE, AND THE FOREST SPEAKS A NIGHTMARE 🩸 What was thought to be another missing-person case turned into a grotesque revelation when hikers stumbled upon the hollowed trunk, realizing the wilderness had been hiding a chilling secret, and investigators were left piecing together a story of cruelty and concealment that sent shivers through the state 👇

The first thing people noticed was the silence. Not the peaceful kind that hikers chase, but the wrong kind, the…

🌾 FARM BOY VANISHES IN 2014 — THREE YEARS LATER POLICE STUMBLE ON HIS SHIRT HANGING IN AN ABANDONED WAREHOUSE, AND THE CASE TURNS CHILLING 🩸 What started as a small-town missing-person report exploded into a nightmare when investigators found the boy’s clothing swaying in the dusty, empty building, suggesting he hadn’t just wandered off, but that someone—or something—had been keeping the secret hidden in plain sight all along 👇

In Milbrook County, mornings began before the sun showed its face. The fields didn’t wait for daylight. Neither did the…

NIGHTMARE IN THE OREGON MOUNTAINS — NEWLYWEDS VANISH, ONLY TO BE FOUND 10 MONTHS LATER IN BAGS STUFFED WITH FEATHERS 😱 What was supposed to be a romantic escape turned into a chilling mystery, and when authorities finally discovered the grisly scene, the town recoiled in horror, realizing the couple’s disappearance had been no accident—but a meticulously hidden, bone-chilling crime that left everyone questioning who could commit such a grotesque act 👇

The Vanishing: A Tale of Love and Mystery in the Oregon Mountains In the heart of the majestic Oregon Mountains,…

⛺ HORROR UNDER THE PAVEMENT — TWO SISTERS VANISH ON A HIKE, ONLY TO BE FOUND THREE YEARS LATER WRAPPED BENEATH A GAS STATION FLOOR 🩸 What started as a carefree adventure became a nightmare etched into local legend, and when workers lifted the floorboards, the discovery left cops, families, and neighbors reeling—proof that the sisters’ disappearance wasn’t random, it was deliberate, hidden beneath the very streets people walked every day 👇

The Vanishing Echoes of the Mountains In the heart of the Cascade Mountains, a chilling mystery unfolded that would haunt…

End of content

No more pages to load