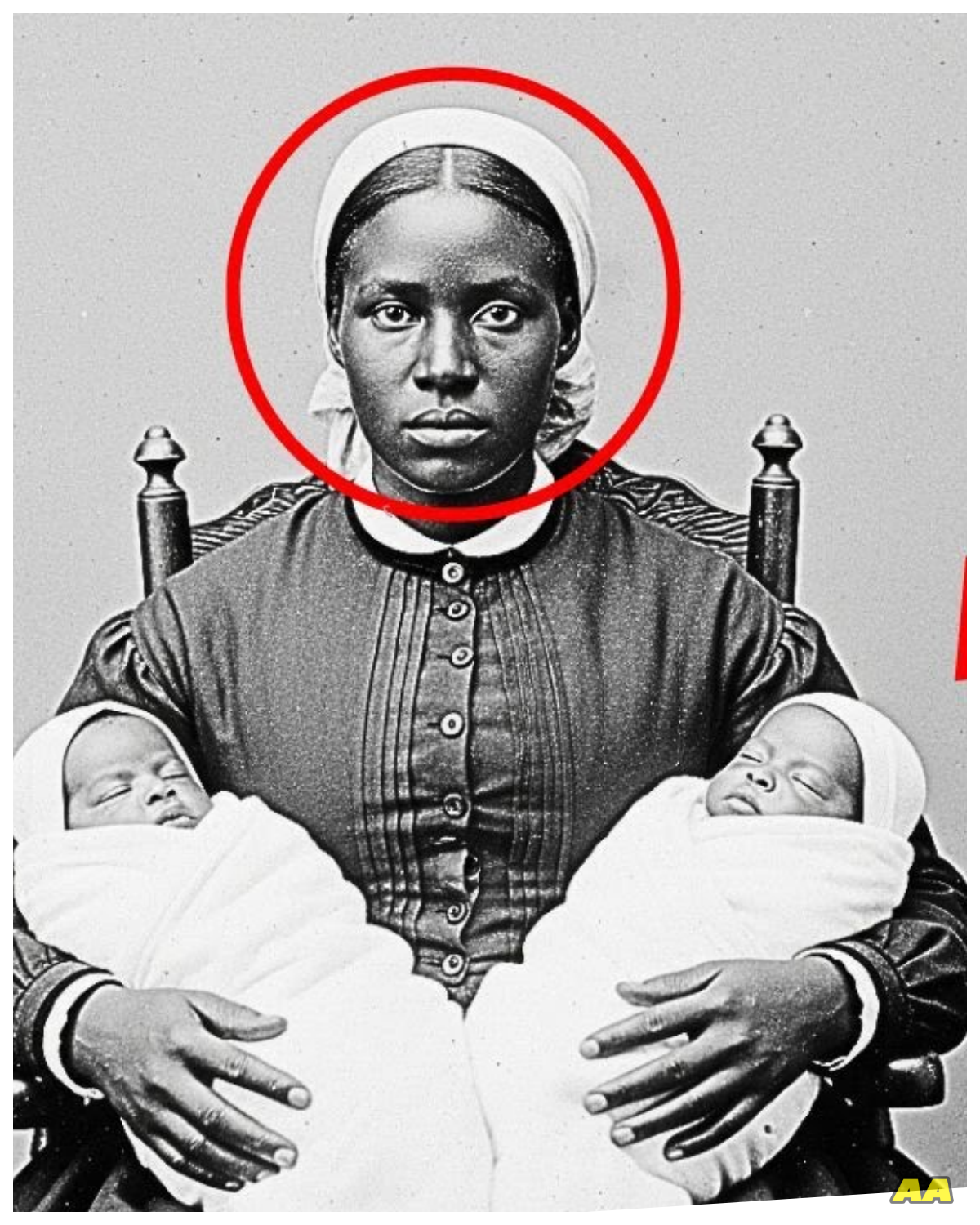

It was just a portrait of a mother and her children.

But when experts zoomed in, they pald.

Rebecca Turner had attended dozens of estate auctions over 15 years as a curator at the National Museum of American History.

But the Whitfield estate sale in Richmond, Virginia felt different.

The family had occupied the same colonial mansion since 1802, and generations of accumulated possessions filled three floors and two outbuildings.

Most attendees came for the furniture and silver, but Rebecca was interested in something less tangible.

the family’s extensive collection of photographs and documents.

She arrived early on that cold morning in February 2024, her breath forming clouds in the unheated auction house.

The photographs were lot 47, described in the catalog simply as miscellaneous degara types, amber types, and paper prints circa 18501 1920.

Condition varies.

Rebecca had learned that such vague descriptions often hid treasures or at least historically significant pieces that deserve preservation and proper documentation.

When Lot 47 came up, only two other biders showed interest.

Rebecca won with a bid of $800, probably more than the photographs were worth monetarily, but the museum’s acquisition budget allowed for speculative purchases that might yield important historical artifacts.

The box arrived at her office 3 days later.

Inside, wrapped in tissue paper and stored in no particular order, were 63 photographs spanning seven decades.

Rebecca spent the afternoon doing preliminary examination, sorting them by type and approximate date.

Most were family portraits.

Stern-faced ancestors in formal dress, children posed stiffly, wedding photographs, a few outdoor scenes.

Then near the bottom of the box, she found it.

An ambroype in a deteriorating leather case.

The image still remarkably clear despite being more than 160 years old.

The photograph showed a young black woman, probably in her early 20s, sitting in a simple wooden chair.

She held two infants, one cradled in each arm.

The babies appeared to be twins, perhaps 3 or four months old, wrapped in plain white blankets.

The woman’s face was striking.

Not because of conventional beauty, though she was beautiful, but because of her expression.

Most photographs from this era showed subjects with neutral or solemn faces, the long exposure times making smiles impractical.

But this woman’s expression was different.

Her eyes stared directly at the camera with an intensity that seemed to transcend the decades.

Her mouth was set in a firm line, neither smiling nor frowning.

She looked determined, Rebecca thought, or perhaps defiant.

Rebecca turned the case over, looking for any inscription or photographers’s mark.

Nothing.

The case itself was plain, lacking the ornate decoration common in expensive amber types.

The next morning, Rebecca arrived at her office early, unable to stop thinking about the photograph.

She had worked with thousands of historical images, but few had affected her the way this one did.

There was something in the woman’s eyes, something urgent and profound that seemed to reach across more than 160 years.

She carefully removed the ambroype from its case and placed it on her light table, examining it with a magnifying glass.

The image quality was excellent.

Whoever had taken this photograph had been skilled.

The focus was sharp, the exposure well balanced, the composition thoughtful despite its simplicity.

Rebecca studied every detail.

The woman wore a plain dark dress with long sleeves and a high collar typical of the 1860s.

Her hair was covered with a simple cloth wrap.

The twins were dressed identically in white gowns, their tiny faces peaceful in sleep or the stillness required by the long exposure.

The chair was rough hue, utilitarian.

The background showed a plain wall, possibly inside a simple building.

Then Rebecca noticed something that made her pause.

She adjusted the magnifying glass, focusing on the woman’s wrists.

The sleeves of her dress extended to just above where her hands held the babies, and at the edge of the fabric, Rebecca could see marks on the skin.

She moved to her desk and pulled out a highresolution digital scanner specifically designed for fragile historical photographs.

30 minutes later, she had a digital file that could be enlarged without damaging the original image.

Rebecca opened the file on her computer and zoomed in on the woman’s left wrist.

What she saw made her breath catch.

circular marks dark against the lighter brown of the woman’s skin.

They formed a band around her wrist approximately an inch wide.

The scarring unmistakable even in the black and white image.

Rebecca zoomed in on the right wrist.

The same marks identical in width and pattern.

Shackle scars.

This woman had worn iron restraints long enough and tightly enough to leave permanent marks on her skin.

Rebecca sat back in her chair, her mind racing.

She looked at the photograph again, seeing it now with completely different eyes.

The date based on the photographic technique and the woman’s clothing.

This was almost certainly from the early 1860s, the American Civil War, the height of slavery in the South.

This wasn’t just a portrait of a mother with her children.

This was a photograph of an enslaved woman.

But why would someone photograph her? And why did she have such an intense, determined expression? Rebecca reached for her phone and called Dr.

James Wilson, a colleague who specialized in Civil War history.

“I need you to look at something,” she said.

“I think I found something important.

” Dr.

James Wilson arrived at Rebecca’s office at exactly 11:15, still wearing his teaching jacket.

At 58, he had spent three decades studying the Civil War period, with particular focus on slavery, resistance movements, and the experiences of black Americans during that era.

His published works included two definitive books on the Underground Railroads operations in Virginia and Maryland.

Rebecca had the digital image displayed on her large monitor when he entered.

Without saying anything, she gestured toward the screen.

James approached, adjusted his glasses, and studied the photograph in silence for a full minute.

Where did you get this? He finally asked, his voice quiet but intense.

Estate auction.

The Whitfield family collection from Richmond.

Do you know them? I know of them.

Major plantation owners, Confederate sympathizers during the war.

James pulled a chair closer to the screen.

May I? Rebecca handed him the mouse, and he began examining the image, zooming in and out, studying different sections.

He spent several minutes on the woman’s face, then moved to her wrists, then to the babies, then to the background details.

This is extraordinary, he said finally.

Rebecca, do you understand what you have here? A photograph of an enslaved woman with shackle scars, but I don’t understand the context.

Why does this photograph exist? James zoomed back to the woman’s face.

Look at her expression.

Really look at it.

This isn’t the face of someone posing for their owner’s amusement.

This is the face of someone who chose to have this photograph taken.

This is intentional, purposeful, he pointed to the shackle scars on her wrists.

These marks are old, probably at least a year old when this photograph was taken, maybe more.

She wore heavy restraints for a significant period, months at least.

What would cause that during slavery? Rebecca asked, though she suspected the answer.

Attempted escape usually, or being classified as a habitual runaway.

Some plantation owners kept certain enslaved people in chains as a deterrent to others.

James’ voice was heavy with controlled anger.

But here’s what’s significant.

She’s not in chains in this photograph.

She’s free enough to be sitting for a portrait, holding two infants who appear healthy and well cared for.

Oh, he zoomed in on the babies.

Twins, probably 3 to four months old based on their size.

And look, they’re dressed identically in clean white gowns.

Someone cared enough to present them well for this photograph.

James sat back thinking, “The timing is crucial.

Based on the amber type technique and the clothing, this is almost certainly 1862 or 1863.

Virginia was Confederate territory, but the Union Army was nearby.

It was a period of tremendous chaos and upheaval.

It was also when many enslaved people were running away.

Over the next week, Rebecca and James worked together to investigate the photograph’s origins.

They started with the Whitfield family records, requesting access to the family’s papers, which had been donated to the Virginia Historical Society decades earlier.

The collection was extensive, plantation ledgers, correspondents, legal documents, and personal diaries spanning two centuries.

Rebecca and James focused on the period from 1860 to 1865, searching for any mention of escaped slaves, particularly a woman with twin infants.

In Colonel Marcus Whitfield’s personal diary from 1863, they found an entry dated May 17th that made them both stop reading.

Received word today that the woman Hannah has fled Riverside with her twin infants, born, but three months passed.

Sheriff Morrison believes she is headed north toward Union lines, have offered a reward of $300 for her return and $50 each for the infants.

She is a habitual runaway, having attempted escape twice before.

It is marked accordingly.

She is considered dangerous and may be armed.

Rebecca looked at James.

Hannah.

Her name was Hannah.

James was already searching through more documents, and she had tried to escape twice before.

That explains the shackle scars.

She’d been punished for previous attempts, but wasn’t deterred.

They continued reading through Whitfield’s diary.

Entries over the following weeks mentioned the ongoing search for Hannah and her twins.

Local patrols had been organized, rewards posted, and neighboring plantations put on alert.

But there were no entries indicating she had been captured.

On June 3rd, 1863, Whitfield wrote, “No word of Hannah.

Sheriff Morrison believes she has successfully reached Union lines or perished in the attempt.

Have written off the loss in the plantation ledger.

She was valued at $1,200, the infants at 400 combined.

” “Written off?” Rebecca said quietly, as if she were property that had simply been misplaced.

James pulled up maps on his laptop.

Richmond in May 1863.

Union forces were operating in the area.

If Hannah was heading north from Riverside, that’s 30 mi of Confederate territory she’d have had to cross with two three-month-old babies.

How would that even be possible? Rebecca asked.

Traveling on foot with infants, evading patrols, finding food and shelter.

It would have required help, James said.

The Underground Railroad was still operating during the Civil War, though it was more dangerous than ever.

There were safe houses, sympathetic free black communities, and some white abolitionists willing to risk harboring fugitives.

Rebecca returned to the Whitfield family papers and found plantation ledgers listing enslaved people by name.

In the 1860 ledger, she found Hannah’s entry.

Hannah, female, age 18, house servant, troublesome disposition, prone to running.

She was only 18 in 1860, Rebecca said, which means she was about 21 when she escaped with her babies.

James spent the next several days researching photographers who had operated in Virginia during the Civil War period, particularly those with known abolitionist sympathy.

Most commercial photographers of the era had left records, but the amber type of Hannah bore no photographers’s mark, which suggested it had been taken by someone who deliberately avoided leaving identifying information.

I think we’re looking for someone connected to underground railroad operations, James said.

A photographer who worked secretly documenting fugitive slaves without creating evidence that could be traced back to them.

He pulled up a list of known underground railroad operatives in Virginia during the 1860s.

One name kept appearing in multiple sources.

a Quaker man named Thomas Garrett who operated out of a small town called Ashland about 15 miles north of Riverside Plantation.

Garrett was a merchant publicly, but records suggest he was deeply involved in helping fugitive slaves.

James explained he’d been arrested twice for harboring runaways, but never convicted.

After the war, several formerly enslaved people testified that he’d helped them escape.

Rebecca called the Quaker Historical Society in Pennsylvania, where Garrett’s papers were housed.

The archist confirmed they had his journals in correspondence and agreed to scan relevant documents.

The scans arrived 3 days later.

In an entry dated May 23rd, 1863, they found what they were looking for.

A young woman arrived last night with twin infants, having traveled from the Riverside area through great hardship.

She bears the marks of cruel treatment, but shows remarkable strength of spirit.

Made arrangements for her photograph to be taken this morning, as is our practice with those in greatest danger.

She wishes her children to be remembered should the worst occur.

That’s her, Rebecca breathed.

That’s Hannah.

May 23rd, 6 days after Whitfield’s diary says she escaped, James was reading ahead.

And look at this.

2 days later, our visitors departed this morning with guides who will take them to the next station.

The woman showed me the scars on her wrists and said, “I will die free or not at all, but my children will never wear chains.

Such courage moves me deeply.

” Rebecca felt tears welling up.

Hannah’s voice, silent for more than 160 years, spoke clearly through Garrett’s words.

They found another reference in Quaker meeting minutes from 1865.

Thomas Garrett acknowledged his work during the war years helping fugitive slaves reach freedom.

He noted that he had learned the photographic arts to create documentation for those in greatest peril that their stories might not be lost.

He learned photography specifically for this purpose.

Rebecca said he was creating a visual archive of people escaping slavery.

James nodded, which explains how this ended up in the Whitfield collection.

After the war, photographs and papers were scattered.

Hannah’s image somehow made its way back to the family she’d escaped from.

The irony is profound.

Finding records of individual fugitive slaves in Union Army archives proved challenging.

Thousands of formerly enslaved people had fled to Union lines during the Civil War, and recordkeeping had been inconsistent.

Some military units documented the refugees carefully.

Others kept minimal records, or none at all.

James started with units that had been operating in Virginia in late May 1863.

The Army of the PTOIC had been active in the region following the Battle of Chancellor’sville.

Several regiments maintained contraband camps where fugitive slaves were given shelter and sometimes employment.

After days of searching through digitized records at the national archives, James found a promising reference.

It appeared in the daily log of a contraband camp near Alexandria, Virginia, dated May 28th, 1863.

Received today one female refugee approximately aged 21 with twin male infants age approximately 3 months.

Woman gives name as Hannah escaped from Riverside Plantation in Richmond area.

Bears visible scars on wrists from shackles.

states she traveled six days through Confederate territory with assistance from underground railroad contact.

Infants in good health despite journey.

Woman assigned quarters in Freiedman’s section, given rations and employment in Camp Laundry.

Rebecca and James read the entry multiple times, relief washing over them.

Hannah had made it.

She had crossed 30 mi of hostile territory with two babies and reached Union protection.

James continued searching and found more references.

A census of contraband camp residents from June 1863 listed Hannah, female, aged 21, with twin sons, Samuel and Jacob, age 4 months.

Medical records from July noted treatment for old scarring on wrists and back, healed whip marks.

Samuel and Jacob, Rebecca said softly.

She named them.

They weren’t just property to be written off in a ledger.

They were her sons, and she gave them names.

James found an employment record from August 1863 showing Hannah had been hired as a laress for the camp, earning wages for the first time in her life.

A letter from the camp superintendent to union officials in September described her as a woman of remarkable determination and work ethic who has saved nearly all her wages with the intention of establishing an independent household.

Then in November 1863, they found a transportation manifest listing Hannah and her twins among refugees being relocated to a Freedman’s community in Philadelphia.

The notation read, “Traveling with letter of recommendation from Superintendent Wallace, literate, skilled in domestic work, seeking employment and housing for herself and two infant sons.

She went to Philadelphia,” Rebecca said.

And she was literate.

That’s unusual for someone who had been enslaved.

She must have taught herself, probably in secret, knowing it was illegal.

James searched Philadelphia city directories and census records from 1864 onward.

It took hours of cross referencing, but finally he found her.

Hannah Freeman, widow, aged 22, Lundress, residing at 147 Lombard Street with two sons, Samuel and Jacob, age one year.

Freeman, Rebecca said she took the surname Freeman, a declaration of her status.

Over the following weeks, Rebecca and James traced Hannah’s life in Philadelphia through city directories, census records, and church documents.

The story that emerged was one of remarkable perseverance and determination.

In 1864, Hannah worked as a laundress while raising her twin sons in a small room in a boarding house in Philadelphia’s Seventh Ward, a predominantly black neighborhood.

Despite the challenges of single motherhood and the limited opportunities available to black women, she managed to save money and build connections within the community.

Church records from Mother Bethl AM Church showed Hannah had become a member in January 1865.

A notation in the membership book described her as a woman of strong faith who escaped bondage in Virginia with her infant sons seeking to build a godly life in freedom.

By 1866, city directory listings showed Hannah had moved to a small house on South Street and had expanded her work beyond laundry.

She was listed as Hannah Freeman, laress, and seamstress, indicating she had developed additional skills to increase her income.

Census records from 1870 provided more detail.

Hannah, now aed 28, owned her small house free of mortgage.

A remarkable achievement for a woman who had been enslaved just seven years earlier.

Her sons, Samuel and Jacob, age seven, were both listed as attending school, something that would have been impossible under slavery.

But the most significant discovery came from Philadelphia’s black community newspapers.

James found an article from 1871 in the Christian Recorder, an AM church publication that featured Hannah’s story, Mrs.

Hannah Freeman, a respected member of our community, has opened her home as a boarding house for newly arrived refugees from the south.

Having herself escaped the bonds of slavery eight years past with her infant twin sons, she now dedicates herself to helping others make the transition to free life in our city.

Mrs.

Freeman provides not only lodging, but also assistance in finding employment and navigating the challenges faced by those seeking to establish themselves in freedom.

Rebecca felt her chest tighten with emotion.

Hannah hadn’t just survived and built a life for herself and her sons.

She had dedicated herself to helping others who were making the same desperate journey she had made.

James found more references to Hannah’s work in subsequent years.

By 1875, she had formalized her efforts, working with the Pennsylvania Abolition Society and local churches to create a network of support for black refugees from the South.

Records showed she had helped more than 50 families find housing and employment in Philadelphia.

Photographs from a community gathering in 1878 included an image of a group of black women involved in charitable work.

Among them, standing in the back row, was a woman whose face bore a striking resemblance to the young Hannah from the 1863 Amberype.

The caption identified her as Mrs.

H.

Freeman, founder of the Refugee Aid Society.

That’s her, Rebecca said, studying the photograph.

15 years older, but you can see it in her eyes, that same determination.

As Rebecca and James continued their research, they turned their attention to Hannah’s twin sons, Samuel and Jacob.

What had become of the babies she had risked everything to save from a life of slavery? City directories and school records provided a clear picture of their childhoods.

Both boys attended the Institute for Colored Youth, a prestigious school in Philadelphia that prepared black students for professional careers.

This was significant.

Hannah had not only ensured her son’s freedom, but had given them educational opportunities that would have been unthinkable under slavery.

Samuel, the older twin by minutes, according to family records, graduated from the institute in 1876 at age 13 and continued his education.

By 1880, census records listed him as Samuel Freeman, age 17, teacher, working at a black school in South Philadelphia.

Jacob took a different path.

Records showed he had apprenticed with a printer and by 1881 was working as a compositor for the Christian Recorder, the same newspaper that had featured his mother’s story years earlier.

But the most remarkable discovery came from a small black newspaper called the Philadelphia Tribune.

In an 1889 article commemorating the work of local civil rights activists, there was a feature on Samuel Freeman, now a prominent teacher and community organizer.

Mr.

Samuel Freeman, age 26, has dedicated his life to education and the advancement of our race.

Born into slavery in Virginia, he was carried to freedom as an infant by his courageous mother, who escaped bondage during the war.

Mr.

Freeman says his mother’s sacrifice inspires his work every day.

She gave me the greatest gift possible, the chance to live as a free man and to use my freedom to help others.

The article went on to describe Samuel’s work establishing night schools for black workers who hadn’t had access to education and his advocacy for better conditions in Philadelphia’s black neighborhoods.

James found similar references to Jacob.

In 1892, the Christian Recorder published an editorial written by Jacob Freeman about the ongoing struggle for civil rights.

The piece opened with a powerful paragraph.

I am the son of a woman who wore shackles on her wrists so that I would never have to wear them on mine.

My mother escaped slavery carrying me and my brother, two infants, through 30 mi of hostile territory because she believed we deserved freedom.

Every day of my life, I worked to honor her courage and to ensure that the freedom she fought for extends to all our people.

Rebecca felt overwhelmed by the weight of what they had discovered.

Hannah’s desperate act of courage in 1863 had rippled forward through generations.

Her sons had become educators, writers, and activists, using the freedom she had won for them to fight for others.

Census records from 1900 showed both brothers still living in Philadelphia, now married with children of their own.

Samuel had become principal of a school.

Jacob was listed as editor of a community newspaper.

And Hannah, now 58 years old, lived with Samuel’s family, described in the census as mother, refugee from slavery, community worker.

Hannah lived to see the new century, surviving until 1904 when she died at age 62.

Her obituaries in the Philadelphia Tribune provided a detailed account of her remarkable life.

Mrs.

Hannah Freeman, a pillar of our community and a woman of extraordinary courage, passed peacefully on March 12th, surrounded by her sons, daughters-in-law, and eight grandchildren.

Born into slavery in Virginia, Mrs.

Freeman escaped bondage in 1863, carrying her infant twin sons through Confederate territory to reach Union lines.

In Philadelphia, she built a new life, working tirelessly not only to provide for her family, but to help countless other refugees from the south establish themselves in freedom.

Her boarding house on South Street became known as a place of refuge and hope.

She survived by her sons Samuel and Jacob, both prominent members of our community and by eight grandchildren who carry forward her legacy of courage and service.

The funeral service was held at Mother Bethl amme church where Hannah had been a faithful member for nearly 40 years.

James found a description of the service in church records.

More than 300 people attended, including dozens of families that Hannah had helped over the years.

One of the eulogies was delivered by Reverend Benjamin Tanner, a prominent minister and civil rights leader.

His handwritten notes for the eulogy had been preserved in church archives.

Sister Hannah’s life was a testament to the power of a mother’s love, and the strength of the human spirit.

She endured what we can barely imagine, the brutality of slavery, the terror of escape, the uncertainty of freedom.

But she never allowed those experiences to embitter her or turn her away from helping others.

Instead, she dedicated her life to ensuring that others would not suffer as she had suffered, that other children would have the opportunities her sons had been given.

She was a living reminder that our freedom was won at great cost, and that we have a responsibility to use that freedom wisely and generously.

Rebecca and James also found something else in Mother Bethl’s archives, a collection of personal items that Hannah had donated to the church in 1902, 2 years before her death.

Among them was a small leather case containing an amber type photograph.

The church archavist pulled out the case carefully.

Rebecca’s hands trembled as she opened it.

Inside was a second copy of the photograph.

They had been studying for months, Hannah sitting in a chair, holding her twin infant sons, her wrists bearing the scars of shackles, her face showing that remarkable expression of determination and defiance.

On the back of the case, in faded handwriting, was an inscription taken May 23rd, 1863 at the house of Thomas Garrett, Ashlin, Virginia, as we fled toward freedom.

I was 21 years old.

My sons Samuel and Jacob were three months old.

We survived.

We are free.

May this image remind future generations that courage is possible and that a mother’s love can overcome any obstacle.

Hannah Freeman, written September 1902.

The exhibition at the National Museum of American History opened on a warm day in September 2024.

Almost exactly 161 years after Hannah had sat for her photograph, Rebecca had spent six months working with museum designers, historians, and descendants of Hannah’s family to create a comprehensive presentation of her story.

The centerpiece was the original amber type from the Whitfield collection displayed alongside the second copy from Mother Bethl amme church.

Seeing the two photographs side by side was powerful.

The same image, but one had been kept by the family that had enslaved Hannah, while the other had been treasured by Hannah herself and eventually given to her community.

The exhibition traced Hannah’s full story.

the brutality of slavery at Riverside Plantation, her previous escape attempts and the punishment she endured, her desperate flight in May 1863 with her infant sons, Thomas Garrett’s role in photographing and protecting her, her journey to Union lines, and her remarkable life in Philadelphia, building not just a future for her own family, but helping dozens of other families escape the South and establish themselves in freedom.

Photographs, documents, newspaper articles, and personal items told the story in vivid detail.

Rebecca had also included information about Hannah’s sons and grandchildren, showing how her act of courage had rippled through generations.

The opening drew more than 400 people, including more than 30 descendants of Hannah who had gathered from across the country.

Among them was Dr.

Marcus Freeman, a 78-year-old retired professor and Hannah’s great great grandson.

Doctor Freeman stood before the photograph of his great great grandmother for a long time, tears streaming down his face.

When he finally spoke to the assembled crowd, his voice was thick with emotion.

I am here today because 161 years ago, a 21-year-old woman made the most courageous decision imaginable.

She decided that her children would not live the life she had been forced to live.

She decided that freedom was worth any risk, any hardship, any sacrifice.

And because of that decision, I exist.

My children exist, my grandchildren exist, and we are all here because she refused to accept that slavery was inevitable or permanent.

He paused, looking again at the photograph.

But what moves me most is not just that she escaped.

It’s what she did after.

She could have focused solely on her own family, on building security for herself and her sons.

Instead, she spent the rest of her life helping others.

She opened her home.

She shared her resources.

She used her own experience to guide others on the same journey.

That is the legacy I want people to remember.

Not just the courage of her escape, but the generosity of her freedom.

Rebecca stood at the edge of the crowd, watching as descendants met each other for the first time, as strangers were moved to tears by Hannah’s story.

As teachers made plans to share this history with their students.

She thought about that February day when she had first opened the box from the Whitfield estate auction and found the photograph.

If she hadn’t looked closely, if she hadn’t noticed the marks on Hannah’s wrists, if she hadn’t been curious enough to investigate further.

The photograph might have been cataloged as simply unidentified woman with children circa 1860s and stored away.

Hannah’s story remaining untold, but she had looked closely.

And in looking closely, she had uncovered not just one woman’s story, but a testament to the power of maternal love, the reality of resistance during slavery, the networks of support that made escape possible, and the ways that courage and determination could transform not just one life, but generations of lives.

That evening, after the crowds had left, Rebecca stood alone in the exhibition space, looking at Hannah’s photograph one final time.

The young woman’s eyes still held that same intensity, that same determination.

But now, Rebecca understood fully what that expression meant.

It was the look of someone who had decided that no matter the cost, no matter the risk, her children would be free.

It was the look of someone who knew she might not survive the journey, but was willing to die trying.

It was the look of someone who refused to let injustice have the final word.

Hannah’s hands, visible in the photograph holding her sleeping sons, bore the scars of shackles.

But those same hands had carried her children to freedom.

Those same hands had worked to build a new life.

Those same hands had reached out to help countless others make the same journey.

The photograph, taken as a precaution in case the worst happened, had become instead a celebration of survival, a testament to courage and proof that one person’s determination to fight for freedom could echo through more than a century and a half, inspiring generations yet unborn.

Hannah had wanted her children to be remembered if something went wrong, but something had gone right.

She had made it.

She had survived.

She had built a life.

And now, 161 years later, her story was finally being told in full.

Not just as a tale of suffering, but as a powerful reminder that resistance is possible, that love can overcome impossible odds, and that the fight for freedom and dignity is never in vain.

News

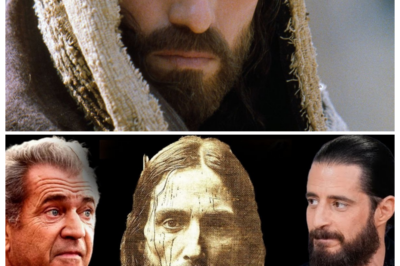

🎭 “I CARRIED THE CROSS OFF CAMERA TOO” — JIM CAVIEZEL FINALLY BREAKS HIS SILENCE ABOUT THE PASSION OF THE CHRIST AND REVEALS THE PAIN THAT NEVER STOPPED 🔥 In a trembling confession years after the cameras stopped rolling, Caviezel describes lightning strikes, broken bones, and eerie accidents that shadowed the set, hinting the suffering didn’t end with “cut,” but followed him home like a curse, leaving him wondering whether the role changed his soul forever 👇

The Silent Echoes of Truth In the dimly lit room, Jim Caviezel sat alone, shadows dancing across the walls. The…

🔥 “THEY DIDN’T WANT YOU TO READ IT” — MEL GIBSON CLAIMS THE ETHIOPIAN BIBLE WAS ‘BANNED’ AFTER CHURCH LEADERS DISCOVERED PASSAGES TOO POWERFUL TO CONTROL 📜 In a tense, late-night interview, Gibson alleges ancient texts hidden for centuries contain forbidden prophecies, missing books, and teachings that challenge everything modern Christianity was built on, warning that once believers see what was removed, “faith will never look the same again” 👇

The Forbidden Pages of Faith In the shadowy corridors of history, where whispers of the past linger like ghosts, Mel…

⚰️ MEL GIBSON STUNNED SILENT AS LAZARUS’ TOMB IS FINALLY OPENED — WHAT ARCHAEOLOGISTS FOUND INSIDE LEFT THE CREW TREMBLING 💥 Cameras roll as stone is moved for the first time in centuries, dust rising like smoke, and Gibson reportedly freezes mid-step, staring into the darkness as whispers spread that what lies inside doesn’t match anything historians expected, turning a biblical legend into a chilling, heart-pounding discovery that feels more like prophecy than history 👇

The Tomb of Secrets: A Hollywood Revelation The Unveiling of Lazarus: A Revelation That Shook the World In the heart…

🩸 JONATHAN ROUMIE & MEL GIBSON BREAK DOWN IN TEARS OVER THE SHROUD OF TURIN — HOLY RELIC SPARKS RAW CONFESSIONS AND SHOCKING REVELATIONS 💥 What began as a calm discussion turns into an emotional storm as the two stars speak with trembling voices about faith, doubt, and the weight of portraying Christ, their words hanging heavy in the air like incense, leaving viewers stunned as Hollywood meets holiness in a moment that feels less like an interview and more like a reckoning 👇

The Veil of Secrets In the dim light of a forgotten chapel, Jonathan Roumie stood before the ancient relic, the…

🩸 MEL GIBSON BLASTS THE VATICAN — “THEY’RE LYING TO YOU ABOUT THE SHROUD OF TURIN!” — HOLY RELIC ROW ERUPTS INTO GLOBAL FIRESTORM 🔥 Cameras barely start rolling before Gibson leans in, voice shaking with fury, claiming centuries of “carefully managed truth” and hinting that what believers were shown isn’t the whole story, sending historians scrambling, priests bristling, and millions wondering if the world’s most sacred cloth hides secrets too explosive for daylight 👇

The Shroud of Secrets Mel Gibson stood at the edge of a precipice, the weight of centuries pressing down on…

🕊️ POPE LEO JUST REVEALED THE TRUTH ABOUT THE 3RD SECRET OF FATIMA — MILLIONS STUNNED AS VATICAN FALLS INTO SILENCE AND BELLS STOP MID-CHIME 💥 What was supposed to be a quiet theological address turns into a jaw-dropping moment of history as the pontiff allegedly unveils details long whispered about for decades, cardinals freeze in their seats, cameras shake, and believers clutch their rosaries as if the sky itself just cracked open 👇

The Shattering Revelation of Pope Leo XIV In a world where faith often intertwines with doubt, the name Pope Leo…

End of content

No more pages to load