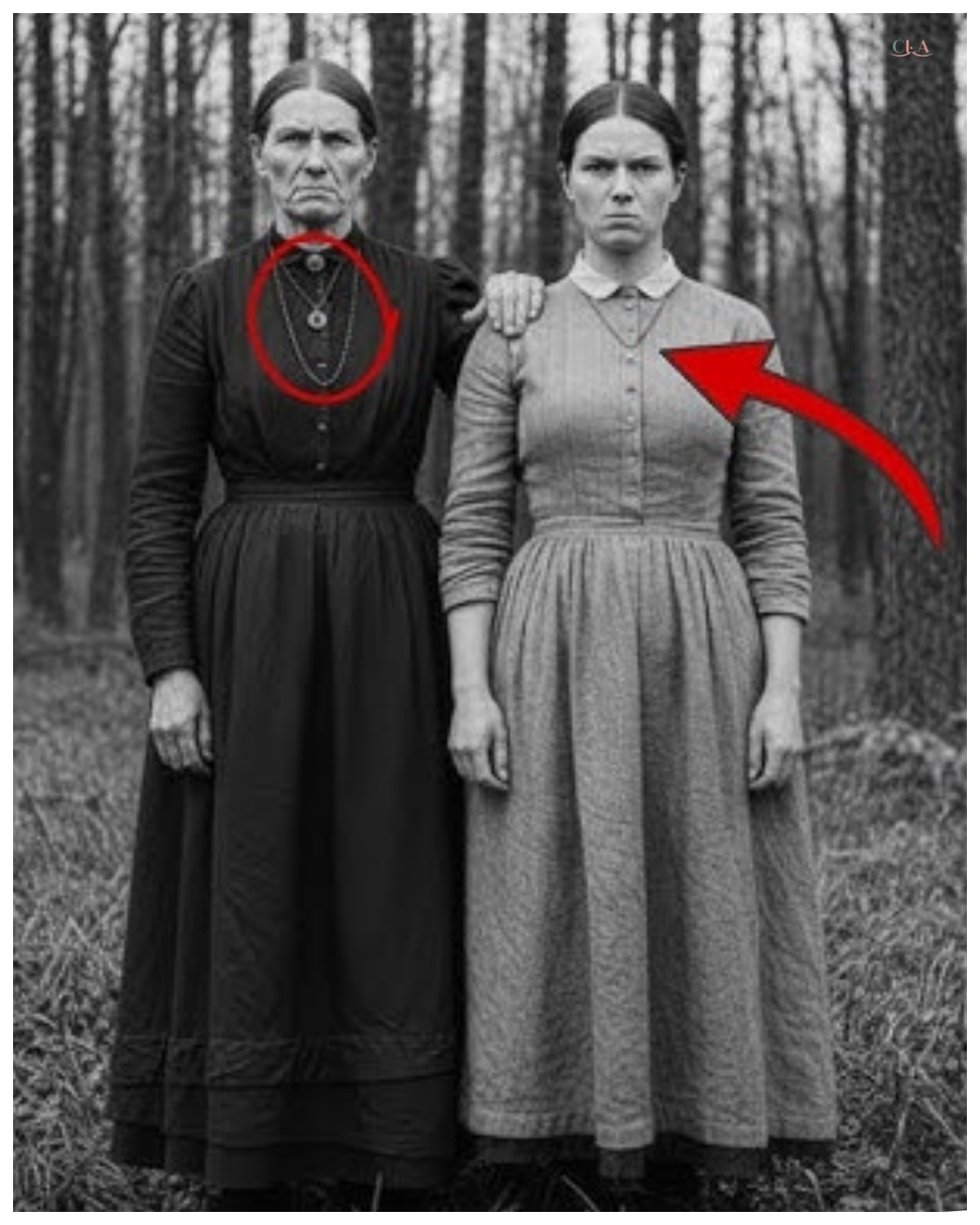

It was just a portrait of a mother and daughter — until you noticed the necklace they both wore

It was just a portrait of a mother and daughter until you noticed the necklace they both wore.

The photograph arrived at Sarah Chen’s office on a Tuesday morning in March 2024, tucked inside a worn cardboard box that smelled of attic dust and old paper.

Sarah, a medical historian at Boston University, had seen thousands of historical images throughout her career.

But something about this one made her pause before she even removed it from its protective sleeve.

The image showed two women standing outside a modest wooden house.

Their expressions serious in the way people posed for cameras in 1887.

The older woman, perhaps in her 40s, wore a simple dark dress with a white apron.

Her hands, rough and capable, rested on the shoulders of a younger woman, barely 20, who stood beside her with the same determined set to her jaw.

Both had dark hair pulled back severely, and both stared directly at the camera with an intensity that seemed to reach across more than a century.

But it was the necklace that caught Sarah’s attention.

Both women wore identical pieces, delicate chains holding small pendants that appeared to be carved from wood or bone.

Sarah leaned closer, her breath fogging the protective glass of her examination lamp.

The pendants were inscribed with what looked like botanical symbols, leaves, flowers, and something that might have been a root system.

Dr.

Chen, her assistant, Michael, appeared in the doorway carrying two cups of coffee.

The donation form says it came from an estate sale in Cambridge.

The family didn’t know much about it, just that it had been in their grandmother’s things for decades.

Sarah accepted the coffee absently, her eyes still fixed on the photograph.

Did they include any documentation, letters, journals, anything? There’s a small leather notebook.

Looks handwritten, but it’s in pretty rough shape.

And there’s this.

Michael held up a small cloth pouch.

Inside, wrapped in yellow tissue paper, was a necklace identical to the ones in the photograph.

Sarah’s hands trembled slightly as she unwrapped it.

The pendant was carved from dark wood, smooth from years of wear.

The botanical symbols were even clearer in person.

Chamomile, raspberry leaf, and something she recognized from her research into traditional medicine.

Blue kohosh, an herb midwives once used during childbirth.

Michael, she said quietly, I think we found something important.

She turned the pennant over in her palm, noticing for the first time that there were tiny initials carved into the back, CM and AK.

The letters were barely visible, worn almost smooth by time and touch.

Someone had worn this necklace for years, perhaps decades.

Someone had valued it enough to keep it safe to pass it down.

Sarah looked back at the photograph at the two women with their matching necklaces and their determined faces.

They weren’t just posing for a picture.

They were documenting something, preserving something, making sure that someone someday would see them and understand.

“Well, let’s start with the notebook,” Sarah said, setting down her coffee.

Whatever these women wanted us to know, I think they left us the evidence to find it.

The leather notebook sat on Sarah’s desk like a challenge.

Its pages were brittle, the ink faded to brown, and the handwriting, cramped and urgent, was almost illeible in places.

Sarah had spent 3 days just preparing to open it properly, consulting with the university’s conservation department to ensure she wouldn’t damage it further.

Now, wearing cotton gloves and using a wooden spatula to gently separate the pages, she began to read.

March 14th, 1887.

Delivered Mrs.

Kowalsski’s fourth child at dawn.

Boy, healthy, 8 pounds.

She had no money, but gave me eggs and bread.

Her husband works at the mill, and they cannot afford the hospital fees.

I did not ask for payment.

The entries continued in the same matter-of-act tone, each one recording a birth, the mother’s name, the baby’s condition, and sometimes a note about payment or lack thereof.

But between these clinical observations, another story emerged.

The hospital on Beacon Street turned away Mrs.

O’Brien today.

They said her kind wasn’t welcome.

Her kind? She’s Irish and poor and her husband died in a factory accident last month.

I will attend her when her time comes.

Sarah’s chest tightened as she read.

The writer, presumably the older woman in the photograph, wasn’t just documenting births.

She was documenting a system of exclusion of deliberate medical neglect based on ethnicity, poverty, and social status.

May 2nd, 1887.

Mrs.

Washington came to me in secret.

She is a negro woman whose mistress does not know she is with child.

The white doctors will not see her.

I promised her I would be there and I will keep my promise.

The notebook spanned 5 years from 1885 to 1890 and contained records of more than 200 births.

Sarah cross referenced the names with city birth records and found something remarkable.

Many of these births had no official documentation, no hospital records, no physician signatures, nothing.

These children had been born in the shadows of official society, delivered by hands that left no trace in the archives.

But the midwife had kept her own records.

She had borne witness.

As Sarah continued reading, she noticed something else.

Every few pages, there was a small symbol drawn in the margin, the same botanical designs from the necklace.

And next to some entries, there were additional initials, AK.

The same letters carved into the back of the pendant.

“Michael,” Sarah called out, her voice tight with excitement.

I need you to search birth records for anyone with the initials AK who was born or lived in Boston between 1865 and 1875 and cross reference it with immigration records from Ireland.

This wasn’t just one woman’s story.

It was two women’s story and Sarah was determined to uncover both of them.

Sarah found the first real clue to the midwife’s identity in an unexpected place, a property deed from 1884.

The address matched the house in the photograph, a small dwelling on what was then the outskirts of Boston, now absorbed into the city’s sprawl.

The deed was registered to a woman named Katherine Morrison.

Armed with this name, Sarah dove into census records, immigration documents, and church registries.

Katherine Morrison, born Katherine O’ullivan in County Cork, Ireland, had arrived in Boston in 1868 at age 19.

She married Thomas Morrison, a dock worker in 1869.

Thomas died in 1876 of tuberculosis, leaving Catherine a widow at 27 with no children of her own.

But the trail went cold after Thomas’s death.

There were no property transactions, no legal documents, nothing.

Until the 1884 deed, when Catherine suddenly had enough money to purchase the house outright.

How does a widowed immigrant woman with no recorded employment buy property? Sarah wondered aloud.

Michael, who had become increasingly invested in the mystery, looked up from his laptop.

Maybe she inherited it.

From whom? Her husband was a doc worker.

His estate inventory listed furniture worth $12.

Sarah tapped her pen against her notebook.

No, she earned this money.

The question is how? The answer came from an unlikely source, a medical journal from 1883.

Sarah had been searching through archives at the Boston Medical Society when she found a heated editorial titled The Problem of Unregulated Birth Attendance.

The author, a prominent physician, railed against ignorant women who practiced midwiffery without formal training, calling them a danger to public health and a threat to legitimate medical practice.

But buried in his diet tribe was a detail that made Sarah’s pulse quicken.

These women charge fees far below what any qualified physician can afford to offer, creating an unfair marketplace that drives patients away from proper medical care.

Katherine Morrison wasn’t just delivering babies out of charity.

She was running a business, one that served patients the hospitals refused to treat, and she was successful enough to buy property.

Sarah pulled out the photograph again, studying Catherine’s face with new understanding.

This wasn’t a simple portrait of a midwife and her helper.

This was a portrait of a businesswoman and her partner, two women who had built something significant in a world that didn’t want to acknowledge their work.

The necklaces suddenly made more sense.

They weren’t just decorative.

They were a symbol of partnership, of shared purpose, of a legacy being deliberately passed from one generation to the next.

But who was AK? Uh, and why had her identity been so carefully hidden from the official record? The young woman in the photograph, the one wearing the matching necklace, proved harder to identify.

The notebook made occasional references to my apprentice or the girl who helps me, but never used a full name.

Sarah spent weeks searching for any connection between Catherine Morrison and young women in the 1880s census data.

checking domestic servants, borders, and distant relatives.

The breakthrough came from an unexpected source, a letter tucked into the back of the notebook that Sarah had initially overlooked.

The paper was different from the notebook pages, finer quality with a watermark.

The handwriting was different, too, younger, more confident, with carefully formed letters.

Dear Catherine, I am writing to tell you that I successfully delivered Mrs.

Brennan’s twins last night.

Both girls, both healthy, though it was a difficult birth.

I used the technique you taught me with the raspberry leaf tea and it helped considerably.

Mrs.

Brennan’s husband is a cooper and has little money, but he made me a beautiful wooden box and payment.

I will treasure it always.

Your grateful student, Anna.

There was no last name, no date, no return address.

But it was a start.

Sarah now had a first name, Anna.

In the initials, AK suggested her last name began with K.

Michael spent three days combing through immigration records, census data, and church baptismal records.

Finally, late on a Friday afternoon, he burst into Sarah’s office with a triumphant expression.

Anna Kelly, he announced, dropping a print out on her desk.

Born in Cork, Ireland in 1867, immigrated to Boston in 1883 at age 16, orphaned.

Both parents died of fever before she left Ireland.

She was sponsored by a women’s aid society and placed in domestic service.

Sarah scanned the document, her heart racing.

Does it say where she was placed? With a widow named Katherine Morrison, Michael said grinning listed as a household servant in the 1885 census.

But here’s the interesting part.

By the 1890 census, she’s listed as Catherine’s ward, not her servant.

And her occupation is listed as medical assistant.

Sarah sat back in her chair, pieces falling into place.

Catherine had taken in a young orphan, given her a home, and trained her in a profession.

The relationship had evolved from employer and servant to mentor and student, and eventually to something like mother and daughter.

They built this together, Sarah murmured, touching the photograph gently.

Catherine taught Anna everything she knew, and Anna carried it forward.

The real scope of Catherine and Anna’s work began to reveal itself when Sarah started cross-referencing the names in the notebook with city records.

She created a database, painstakingly entering each birth recorded in Catherine’s handwriting, then searching for any corresponding documentation in official archives.

The pattern was stark and disturbing.

Of the 247 births recorded in the notebook between 1885 and 1890, only 89 appeared in hospital records.

The rest, 158 births, existed only in Catherine’s careful documentation.

These were children born to women the medical establishment had refused to serve.

Sarah mapped the addresses.

They clustered in specific neighborhoods.

The north end, where Italian immigrants crowded into tenementss.

The West End, home to Irish and Jewish families, and scattered addresses.

is in the south end where black families lived in boarding houses and cramped apartments.

“Look at this,” Sarah told Michael, pointing to her map.

Catherine wasn’t just serving her own neighborhood.

She was traveling all over the city, going wherever she was needed.

The notebook revealed the logistics.

Catherine charged on a sliding scale.

Wealthy families paid $5, working families paid two, and the poorest paid nothing at all, or paid in goods and services.

A loaf of bread, a repaired shoe, a bundle of firewood.

Catherine accepted it all and recorded it meticulously.

But there was something else in the records, something Sarah almost missed at first.

Every few months, there were entries marked with a small star in the margin.

These births had no names attached, just initials and a location.

And they were always attended by both Catherine and Anna together.

March 17th, 1888.

Difficult birth.

Mother survived, but barely.

CM and AK both attended.

No complications with the child.

Mother asked us to find her a safe place.

We obliged.

Sarah’s breath caught.

These weren’t just difficult births.

These were women in crisis.

Women who needed more than medical care.

They needed protection, secrecy, and help that went far beyond delivering a baby.

Catherine and Anna weren’t just midwives.

They were operating something like an underground network, helping women whose circumstances made them vulnerable.

Women escaping abusive situations.

Women whose pregnancies had to be hidden.

Women who had nowhere else to turn.

The necklaces took on yet another meaning.

They were a signal, a way for women in need to identify Catherine and Anna as people who could be trusted, people who would help without judgment, without questions, without involving authorities who might make things worse.

Sarah held the pendant in her hand, understanding now why it had been worn smooth.

It hadn’t just been worn for years.

It had been shown to dozens, maybe hundreds of desperate women who needed to know they were safe.

Sarah’s research took an unexpected turn when she received an email from a woman named Eleanor Rodriguez in response to a query Sarah had posted on a genealogy forum.

Elellanar’s great great-grandmother had been delivered by a midwife in Boston in 1889, and family stories mentioned a necklace with botanical symbols.

They met at a coffee shop in Cambridge on a rainy April morning.

Ellaner, a retired teacher in her 70s, brought a small wooden box that had belonged to her great great grandmother.

Her name was Rosa Martinez, Ellaner explained opening the box carefully.

She came from Mexico in 1888, pregnant and alone.

Her family had disowned her.

She spoke almost no English and was terrified.

Inside the box were letters written in Spanish and a small piece of fabric with botanical symbols embroidered on it.

The same symbols from the necklaces.

Rosa kept this her whole life.

Ellaner said she told my great-grandmother that two women with necklaces like this saved her life.

Not just delivered her baby, but actually saved her life.

They found her a place to stay, helped her find work, taught her enough English to get by.

Without them, she would have died on the streets.

Sarah’s hands trembled as she examined the embroidered cloth.

Do the letters say anything about the midwives? Elellaner nodded, pulling out a translation she’d made.

Rosa wrote to her sister years later after they’d reconciled.

She said the older woman was Irish, stern, but kind.

The younger one was barely older than Rosa herself, but she spoke a little Spanish and held Rosa’s hand through the whole birth.

Rosa said they asked for no payment except that she passed on the kindness when she could.

The letter continued, “They gave me a piece of cloth with their symbols on it and told me that if I ever met another woman in trouble, I should show her this cloth and help her as they helped me.

They said there were others doing the same work, and the symbols would identify us to each other.

” Sarah’s mind raced.

This wasn’t just Catherine and Anna working alone.

They were part of something larger, a network of women helping women, identified by these botanical symbols.

The necklaces weren’t unique to Catherine and Anna.

They were part of a wider system of care that operated in the shadows of official society.

“Did Rosa ever use the cloth?” Sarah asked.

Ellaner smiled.

She helped deliver dozens of babies in her lifetime.

She became a midwife herself, serving the Mexican and Latin American community in Boston, and she passed the tradition to her daughter, and her daughter passed it to me.

I’m a retired nurse.

I like to think I carried on what they started, even if I didn’t know the full story until now.

Armed with Elellaner’s information, Sarah expanded her search.

She contacted historical societies, immigrant aid organizations, and genealological groups across New England, asking about midwives in the late 1800s, and any mention of botanical symbols or necklaces.

The responses flooded in.

A woman in Providence, whose Italian great-g grandandmother had been delivered by a midwife who wore a wooden pendant.

A man in Worcester, whose Polish ancestor had written about the women with the flower necklaces, who helped during difficult births.

a descendant of a Chinese immigrant family in Boston who had a faded drawing of botanical symbols that had been passed down through generations.

Each story added another piece to the puzzle.

The network was larger than Sarah had imagined, spanning multiple cities, multiple ethnic communities, multiple generations.

The symbols appeared in different forms, necklaces, embroidered cloths, carved wooden boxes, even tattoos in some cases.

But they all served the same purpose, identifying women who could be trusted to provide care without judgment or official interference.

Sarah discovered that the network had a practical structure.

Experienced midwives like Catherine trained apprentices like Anna.

Those apprentices eventually established their own practices and trained others.

The botanical symbols were taught along with medical knowledge.

Each plant representing a specific remedy or technique.

Chamomile for calming tees, raspberry leaf for strengthening the womb, blue kohash for managing labor pain.

But the symbols also represented values.

Compassion, discretion, and accessibility.

Women who wore them pledged to serve anyone who needed help, regardless of their ability to pay or their social status.

Michael helped Sarah create a timeline.

The network appeared to have started in the 1870s, possibly earlier, and continued into the early 1900s.

It began to fade as professional nursing programs expanded and as immigrant communities became more established and gained better access to hospitals.

But it never completely disappeared.

Some of the women Sarah interviewed had mothers or grandmothers who practiced midwiffery into the 1940s and 1950s, still using the old symbols, still serving communities that mainstream medicine overlooked.

“Why didn’t anyone document this?” Michael asked, frustrated by the gaps in official records.

Sarah understood.

“Because it was deliberately invisible.

These women were operating outside the medical establishment, sometimes in direct defiance of laws that required births to be registered and attended by licensed physicians.

They kept it quiet to protect themselves and their patients.

The photograph of Catherine and Anna took on new significance.

It wasn’t just a portrait.

It was an act of defiance, a deliberate record of work that was meant to be unseen.

They had documented themselves because they knew that official history would erase them.

The most revealing discovery came from an unexpected source, a diary found in the archives of a settlement house in Boston’s North End.

The settlement house had served immigrant families from 1885 to 1920 and its archives contain letters, photographs, and personal papers donated by families over the decades.

The diary belonged to a woman named Margaret, a settlement house worker who had documented her observations of the neighborhood from 1887 to 1893.

Her entries were detailed and compassionate, recording the struggles and triumphs of immigrant families trying to build lives in America.

One entry from November 1889 caught Sarah’s attention.

Mrs.

Mrs.

Morrison came today to attend to the Rossy family.

Their youngest was born 3 weeks early, and Mrs.

Rossy was frightened, having lost a child in Italy last year.

Mrs.

Morrison brought her apprentice, a young Irish woman who has become quite skilled.

Together, they stayed with the family for 2 days until both mother and child were stable.

They refused payment beyond a meal and some coal for heating.

When I asked Mrs.

Morrison why she does this work for so little compensation, she said something I will not forget.

These women have no voice in the halls where decisions are made about their bodies and their lives.

The least I can do is ensure they have a voice in their own births.

Sarah read the passage three times, her vision blurring with tears.

This was Catherine’s philosophy preserved in someone else’s words.

Autonomy, dignity, the right of women to make decisions about their own medical care.

The diary continued with more observations about Katherine and Anna’s work.

Margaret noted that they were consulted not just for births, but for general women’s health concerns, issues that women were too embarrassed to discuss with male physicians or too poor to afford proper medical care.

Mrs.

Morrison and her assistant maintain a small supply of remedies and herbs.

Women come to them with ailments they dare not speak of elsewhere.

I have seen Mrs.

Morrison treat infections, provide advice on preventing conception, and counsel women on matters of intimate health with a frankness and competence that would scandalize the medical profession.

Yet her patients trust her completely.

Sarah cross- referenced Margaret’s diary with Catherine’s notebook and found something remarkable.

Many of the births Katherine recorded corresponded with Margaret’s observations.

The two women had worked in parallel.

Margaret providing social support and Catherine providing medical care, serving the same vulnerable communities.

But there was something Margaret mentioned that Catherine’s notebook didn’t record.

Katherine and Anna’s work went beyond childbirth.

They were providing comprehensive women’s health care in an era when such care barely existed for poor and immigrant women.

The final piece of the puzzle came from Anna herself.

Sarah discovered a brief obituary in the Boston Globe from 1947.

Anna Kelly, 80, a retired nurse and longtime resident of Cambridge, died peacefully at home.

She was known in her community for her charitable work and her dedication to women’s health.

Following this lead, Sarah contacted the Cambridge Historical Society and found that Anna had donated her personal papers to their collection in 1945, two years before her death.

The archive had never been fully cataloged or studied.

Sarah and Michael spent a week going through boxes of Anna’s materials.

There were letters, photographs, training manuals, and most remarkably, a continuation of Catherine’s original notebook.

Anna had kept recording births and medical cases from 1890 when Catherine’s notebook ended until 1923.

In the front of Anna’s notebook was a letter written in Catherine’s handwriting and dated 1889.

My dear Anna, I give you this notebook to continue the work we have built together.

You came to me as a frightened orphan, and you have grown into a skilled and compassionate healer.

I am proud to call you my daughter in all but blood.

The necklace I gave you is not just a symbol of our profession.

It is a promise.

A promise to serve those whom others turn away.

A promise to treat every woman with dignity, regardless of her circumstances.

I promise to pass on this knowledge and this commitment to others who will carry it forward.

Wear it with honor.

Teach others what I have taught you.

And remember that this work matters even if the world never acknowledges it.

Especially because the world never acknowledges it.

We are witnesses.

We are advocates.

We are the hands that catch these children as they enter the world and the voices that speak for their mothers when no one else will listen.

Anna had added her own note below Catherine’s.

I received this letter on the day Catherine passed away, June 14th, 1889.

I was 22 years old and terrified that I could not continue without her.

But I remembered her words.

We are witnesses.

So I witnessed, I recorded, I served, and I taught others just as she taught me.

This notebook contains the records of 43 women I trained over the years.

Each received a necklace.

Each made the same promise.

The work continues even after I’m gone.

Sarah sat in the archive reading room, overwhelmed.

Catherine had died young, at just 40 years old.

But she had built something that outlasted her by decades.

Through Anna and through the women Anna trained, Katherine’s vision of compassionate, accessible women’s health care had reached hundreds, perhaps thousands of women who would otherwise have had nowhere to turn.

Sarah presented her findings at a medical history conference in October 2024.

The lecture hall was packed with historians, medical professionals, and descendants of immigrant families.

She displayed the photograph of Katherine and Anna on the screen behind her.

The two women with their matching necklaces staring out at an audience that finally understood what they had done.

These women operated in the gaps of official medicine, Sarah explained.

They served patients who were rejected by hospitals because of their ethnicity, their poverty, or their social status.

They provided care that was comprehensive, compassionate, and culturally sensitive.

And they did it without seeking recognition or official sanction because they knew that official recognition would come with restrictions that would prevent them from serving the people who needed them most.

After the presentation, Sarah was approached by dozens of people with their own stories.

a grandson whose Italian grandmother had been delivered by a midwife wearing a botanical pendant.

A nurse whose great aunt had trained with Anna Kelly in 1915, a researcher who had found similar networks operating in Philadelphia and New York.

Eleanor Rodriguez was in the audience and she brought her daughter and granddaughter.

I wanted them to hear this, she said.

To understand where they come from, to know that our family has always been about helping others.

The photograph, Katherine’s notebook, Anna’s records, and the necklace were eventually donated to the Smithsonian Institutions Collection on Women’s Medical History.

Sarah wrote an article for the Journal of American Medical History that was picked up by mainstream media, and suddenly Katherine Morrison and Anna Kelly were no longer invisible.

But the most meaningful moment came months later when Sarah received a letter from a midwife practicing in rural Vermont.

She had read Sarah’s article and wanted to share something.

Her grandmother, who had died in 1998, had left her a wooden pendant carved with botanical symbols.

The grandmother had been trained by a woman who claimed to be part of a long tradition of midwives serving marginalized communities.

“I wear the pendant when I attend births,” the midwife wrote.

“I didn’t understand what it meant until I read your research, but now I do, and I’m honored to carry on what they started in my own way, in my own time.

The work continues.

” Sarah kept that letter on her desk next to the photograph of Katherine and Anna.

Two women who had worn their necklaces as a promise.

A promise that had been kept across generations, passed from hand to hand, mother to daughter, teacher to student, sustained by women who understood that some things matter more than official recognition.

In the photograph, Catherine and Anna still stared out with their determined expressions, their matching necklaces visible against their dark dresses.

They were no longer invisible.

They had been seen, their work acknowledged, their legacy preserved.

But more than that, they had been understood.

And the promise they made to serve, to witness, to care continued in the hands of others who wore the symbols and carried the tradition forward into a new century.

The work continues even after we are gone.

News

🚛 HIGHWAY CHAOS — TRUCKERS’ REVOLT PARALYZES EVERY LAND ROUTE, KHAMENEI SCRAMBLES TO CONTAIN THE FURY 🌪️ The narrator’s voice drops to a biting whisper as convoys snake through empty highways, fuel depots go silent, and leaders in Tehran realize this isn’t just a protest — it’s a nationwide blockade that could topple power and ignite panic across the region 👇

The Reckoning of the Highways: A Nation on the Edge In the heart of Tehran, the air was thick with…

🎬 MEL GIBSON DROPS THE BOMBSHELL — “THE RESURRECTION” CAST REVEALED IN A MIDNIGHT MEETING THAT LEFT HOLLYWOOD GASPING 😱 The narrator hisses with delicious suspense as studio doors slam shut, contracts slide across tables, and familiar faces emerge from the shadows, each name more explosive than the last, turning what should’ve been a simple casting call into a cloak-and-dagger spectacle worthy of a conspiracy thriller 👇

The Darkened City: A Night of Reckoning In the heart of Moscow, a city that once stood proud and unyielding,…

🎬 MEL GIBSON DROPS THE BOMBSHELL — “THE RESURRECTION” CAST REVEALED IN A MIDNIGHT MEETING THAT LEFT HOLLYWOOD GASPING 😱 The narrator hisses with delicious suspense as studio doors slam shut, contracts slide across tables, and familiar faces emerge from the shadows, each name more explosive than the last, turning what should’ve been a simple casting call into a cloak-and-dagger spectacle worthy of a conspiracy thriller 👇

The Shocking Resurrection: A Hollywood Revelation In a world where faith intertwines with fame, the announcement sent ripples through the…

🎬 “TO THIS DAY, NO ONE CAN EXPLAIN IT” — JIM CAVIEZEL BREAKS YEARS OF SILENCE ABOUT THE MYSTERY THAT HAUNTED HIM AFTER FILMING ⚡ In a hushed, almost trembling confession, the actor leans back and stares past the lights, hinting at strange accidents, eerie coincidences, and moments on set that felt less like cinema and more like something watching from the shadows, leaving even hardened crew members shaken to their core 👇

The Unseen Shadows: Jim Caviezel’s Revelation In the dim light of a secluded room, Jim Caviezel sat across from the…

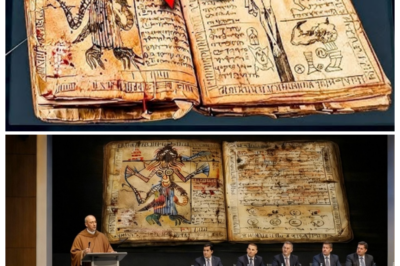

📜 SEALED FOR CENTURIES — ETHIOPIAN MONKS FINALLY RELEASE A TRANSLATED RESURRECTION PASSAGE, AND SCHOLARS SAY “NOTHING WILL BE THE SAME” ⛪ The narrator’s voice drops to a breathless whisper as ancient parchment cracks open under candlelight, hooded figures guard the doors, and words once locked inside stone monasteries spill out, threatening to shake faith, history, and everything believers thought they understood 👇

The Unveiling of Truth: A Resurrection of Belief In the heart of Ethiopia, where the ancient echoes of faith intertwine…

🕯️ FINAL CONFESSION — BEFORE HE DIES, MEL GIBSON CLAIMS TO REVEAL JESUS’ “MISSING WORDS,” AND BELIEVERS ARE STUNNED INTO SILENCE 📜 The narrator’s voice drops to a hushed, dramatic whisper as old notebooks open, candlelight flickers across ancient pages, and Gibson hints that lines never recorded in scripture could rewrite everything the faithful thought they knew 👇

The Unveiling of Hidden Truths In the dim light of his private study, Mel Gibson sat surrounded by piles of…

End of content

No more pages to load