It was just a photo between mother and child.

Zooming in, experts discover something terrifying.

The November rain drumed against the tall windows of the Smithsonian Institution’s photography archive as Dr.

Lauren Hayes carefully positioned another 19th century photograph under her highresolution scanner.

It was late afternoon in Washington DC and she was 6 weeks into digitizing a massive collection of American photographs from the 1890s donated by a deceased collector’s estate.

Most photographs were predictable, formal family portraits, city streetscapes, industrial scenes, and landscapes.

Lauren approached each with professional detachment, documenting details before scanning.

After 23 years as a photographic archavist, she had developed an efficient rhythm and rarely felt surprised.

But then she lifted a particular photograph from its protective sleeve, and something made her pause.

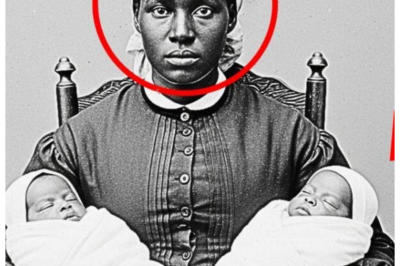

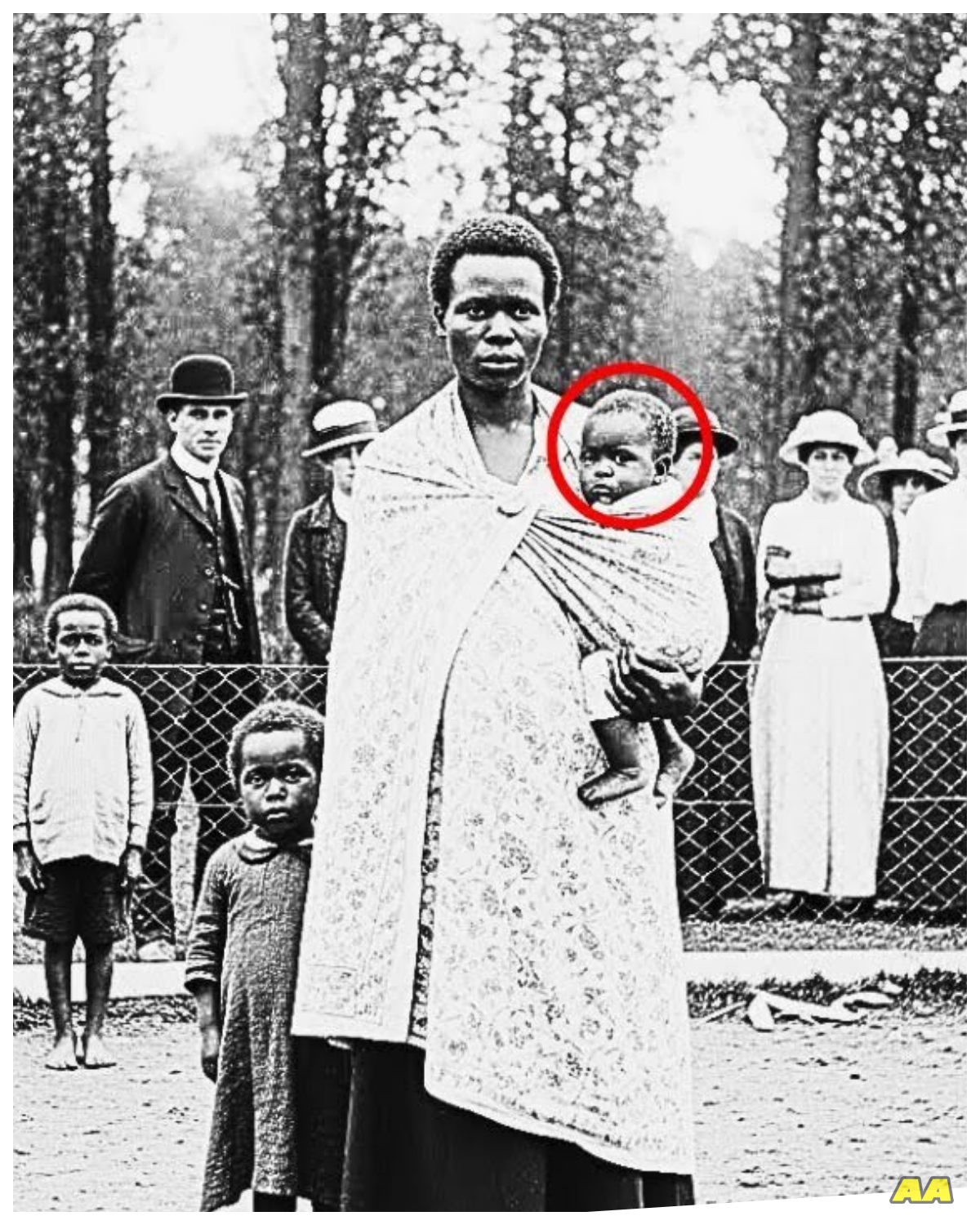

The image showed a black woman, perhaps mid-20s, holding a small child, about 2 years old.

The woman stood in what appeared to be an outdoor setting with foliage visible behind her.

She wore a light colored wrapped garment resembling traditional African dress, her hair styled in elaborate braids.

The child, also dressed in simple cloth, was cradled securely in her arms, one small hand resting against her chest.

What struck Lauren immediately was the woman’s expression.

Unlike most formal photographs from that era, where subjects looked stiff and uncomfortable due to long exposure times, this woman’s face held something different.

a direct penetrating gaze into the camera lens.

There was dignity in her posture, determination in the set of her jaw, but also something else, something that looked like defiance or perhaps desperation masked as strength.

Lauren turned the photograph over.

On the back, in faded pencil, someone had written, “African village, Atlanta, 1897.

” Nothing more.

No names, no specific location beyond Atlanta, no photographers mark.

She studied it more carefully under her magnifying lamp.

The lighting was professional.

the composition carefully arranged.

This wasn’t a casual snapshot, but a deliberate portrait taken by someone with skill and proper equipment.

The woman’s hands drew her attention.

The right arm supported the child naturally, but the left hand was raised slightly, fingers arranged in what seemed like a deliberate gesture.

Lauren photographed the image with her digital camera, capturing the full frame at high resolution.

She uploaded the file to her workstation and began zooming in on different sections, documenting facial features, clothing details, background elements.

She zoomed in on the woman’s face first, noting subtle scarification marks on her cheeks, deliberate ritual scarring indicating specific cultural origins.

She zoomed in on the child, documenting approximate age, and how small fingers gripped the mother’s wrap.

Then she began examining the background, and her routine documentation came to an abrupt halt.

What had appeared as natural foliage and soft outdoor scenery revealed itself under magnification as something entirely different.

Behind the woman and child, partially obscured, but unmistakably present, was a metal fence, not decorative, but heavy gauge wire fencing used for containment.

Beyond the fence, she could see blurred figures, white people in late Victorian clothing, standing and watching.

At the edge of the frame, partially cut off, but visible when magnified, was a wooden sign.

Lauren adjusted the digital enhancement.

The text became barely legible.

Freakingville, Mission 10 C.

Her hands began trembling.

This wasn’t a simple portrait.

This was a human zoo.

Lauren sat motionless, staring at the magnified details on her screen.

She had read about human zoos, the ethnological exhibitions popular in America and Europe during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

She had seen references in historical texts, read scholarly articles about their role in promoting racist pseudocience, but she had never actually handled a photograph from one.

She adjusted the enhancement, increasing contrast and sharpness.

The fence was clearly visible, running vertically through the background about 15 ft behind the subjects.

Beyond it, multiple people dressed in late Victorian clothing stood watching.

Some appeared to be pointing.

One woman held what looked like a parasol.

Several children were visible, their faces pressed close to the fence.

At the far right edge, the wooden sign became clearer with adjustment.

Uh, African village, she could read.

And below, admission 10 cents.

The understanding crashed over her.

This woman had been caged, put on display, forced to perform authenticity for crowds of white spectators who paid admission to gawk at human beings as if they were exotic animals.

And she had been photographed holding her child in this nightmare.

Lauren’s first instinct was to call her supervisor, but she hesitated.

She needed expert confirmation.

She found Dr.

Marcus Thornton’s number, a historian at Howard University who specialized in African-American history and documentation of racial violence.

Marcus, it’s Lauren Hayes at the Smithsonian.

I need you to come look at something today, if possible.

I think I found documentation of a human zoo exhibition.

40 minutes later, Marcus arrived.

Lauren had prepared a presentation, the original photograph at full size, then magnified sections showing the fence, the watching crowd, the partial sign.

She also showed him the woman’s left hand.

Under magnification, it was clearly intentional.

Thumb crossed over her palm, three fingers extended at a specific angle, pinky finger bent inward.

It looked like a sign, deliberate communication.

Marcus studied the images in silence, his jaw tightened as he examined each detail.

Finally, he sat back and removed his glasses.

Where did this come from? A private collection donated last year.

There’s minimal documentation, just that notation about Atlanta, 1897.

Marcus pulled up references on his tablet.

The Cotton States and International Exposition.

It ran in Atlanta from September to December 1897.

It was a major world’s fair celebrating the South’s economic recovery.

He scrolled through historical records, and yes, it featured ethnological villages, human zoos.

They brought people from Africa, the Philippines, indigenous communities, and displayed them in constructed villages for white audiences to observe.

He zoomed in on the woman’s face.

Look at her eyes, Lauren.

She knows exactly what’s being done to her.

She’s refusing to look away.

That’s resistance.

What about her hand position? Marcus studied the gesture.

I’m not certain, but it looks like it could be a communication sign.

Many African cultures had complex systems of non-verbal communication.

If she was trying to send a message, he looked at Lauren with determination.

We need to find out who she was.

This woman had a name, a home, a life before she was brought here and caged.

We need to find out what happened to that child.

Over the following week, Lauren and Marcus assembled a specialized research team.

They needed expertise across multiple disciplines to trace what had happened and identify the people in the photograph.

Dr.

Patricia Chen joined first, a historian specializing in world’s fairs and international expositions, particularly their role in promoting imperialism and racist ideologies.

She had published extensively on ethnological exhibitions at various American fairs.

The Atlanta Exposition wasn’t isolated, Patricia explained.

Between 1870 and 1940, millions attended human zoo exhibitions across America.

They were at major fairs in Philadelphia, Chicago, Buffalo, St.

Louis, San Francisco.

The industry was vast and profitable.

She brought documentation showing the business structures.

Entrepreneurs would contract with fair organizers to provide authentic natives, handling procurement, transportation, housing, and management of exhibited people.

Dr.

James Morrison, a specialist in 19th century photography, analyzed the technical aspects.

This was taken by a professional using highquality equipment.

The lighting is carefully controlled, composition deliberate, and print quality suggests commercial purposes, likely as a souvenir visitors could purchase.

He showed examples of similar photographs.

Postcard- sized prints of people in ethnological villages sold as momentos.

These were extremely popular.

The people depicted were literally commodified.

Their images sold for profit.

Dr.

Amara Okafor, a cultural anthropologist studying West African societies, examined the woman’s appearance and cultural markers.

The scarification pattern on her cheeks is significant.

This type was practiced by specific ethnic groups in West Africa, particularly in coastal regions of what is now Ghana, Togo, and Benine.

She examined the clothing and hair styling.

The wrapping technique and fabric pattern are consistent with traditional dress from the Gold Coast region.

However, I’d need more photographs to determine if she was forced to dress this way for display or chose to wear traditional clothing as cultural preservation.

Most significantly, Amara studied the hand gesture, comparing it to her database of documented West African communication systems.

In several Gaadang Bay cultures from the Gold Coast, a similar position was used to convey meanings related to memory, witness, or testimony.

The crossed thumb, extended fingers, and bent pinky created a sign roughly translating as remember this or do not forget.

If she was making the sign deliberately, she was attempting to communicate something crucial.

Jennifer Blake, their digital imaging specialist, enhanced different sections using advanced restoration software.

She sharpened the blurred background enough to count approximately 15 distinct figures watching beyond the fence.

She enhanced the sign to confirm African village and admission 10 cents.

This establishes it definitively.

Marcus said this was paid exhibition.

People were charged money to view human beings in cages.

The team’s next task was clear.

Find historical records from the 1897 Atlanta Exposition that might identify the specific individuals, trace how they came to be there, and discover what happened after the exhibition ended.

Patricia took the lead in searching for official records from the Cotton States and International Exposition.

She traveled to Atlanta and spent days in archives at the Atlanta History Center, the Library of Congress, and Georgia State Archives.

What she found was both illuminating and disturbing.

The exposition’s official records treated human exhibitions as just another attraction with budget items for procurement of ethnological specimens and maintenance of native villages.

The casual dehumanization in bureaucratic language was chilling.

The breakthrough came when Patricia discovered personal business records of Captain Harrison Bradford, the entrepreneur who had contracted with exposition organizers to provide the African village display.

Bradford’s papers had been donated to a historical society by his descendants, filed away and largely unexamined.

Bradford’s records were extensive and methodical.

He kept careful accounts of expenses and revenues, treating his trafficking operation as straightforward business.

Patricia found contracts, shipping manifests, expense ledgers, and correspondents revealing how the system worked.

In a November 1896 letter to the exposition’s director, Bradford wrote, “I can guarantee delivery of 25 authentic African natives for your ethnological congress, including men, women, and children.

My agents in the Gold Coast have identified suitable specimens from inland villages where natives retain primitive customs.

Transportation and maintenance will be managed professionally.

My fee is $3,000 plus 20% of souvenir photograph sales.

The cold calculation, suitable specimens, primitive customs, maintenance made Patricia physically ill.

But these documents contained information needed to identify the woman and child.

She found the shipping manifest for the vessel that brought Bradford’s specimens to America.

The merchant ship Providence departed ACRA in the British Gold Coast on January 15th, 1897, arriving in Charleston, South Carolina on March 3rd, 1897.

The manifest listed 24 native passengers in custody of H.

Bradford with notation of men, women, and children of various ages, but no individual names beyond their collective designation as cargo.

24 people made that Atlantic crossing, 50 days at sea, held in custody of a man who saw them as inventory.

Bradford’s expense records showed he paid 600 British pounds to procurement agents in Africa, money used to deceive, coers, or force people onto that ship.

Further records showed Bradford transported the group from Charleston to Atlanta by train, arriving late March 1897.

The exposition wouldn’t open until September, meaning these people spent nearly 6 months in preparatory confinement.

Bradford’s notes referred to this as training and acclamation, instructing exhibited people on expected performances and how to present themselves to maximize authentic primitive appearance.

White audiences expected.

Marcus found newspaper articles from Atlanta Papers promoting the upcoming exhibition.

One August article described, “Visitors will have rare opportunity to observe genuine African savages in their natural state, performing heathen rituals and demonstrating the vast gulf between civilized Christian society and the dark continent’s primitive inhabitants.

” The racism was explicit and unashamed.

These weren’t presented as exploitation, but as educational opportunities for white Americans to confirm assumed superiority.

The major breakthrough came from an unexpected source.

Dr.

Okapor had shared the photograph with colleagues in Ghana, asking if anyone recognized the scarification pattern or had information about people who disappeared in the late 1890s under circumstances matching human zoo recruitment.

A community historian named Mensah from Tesier outside Acra responded with information that changed everything.

His family’s oral history included a painful story about a young woman named Amma Oderte who vanished in early 1897 along with her infant daughter.

The family had been told Amma would travel to America for cultural exchange, returning within a year with substantial payment.

She never came back.

Sent detailed information passed through four generations.

Amma was born in 1872 in Teshi, a Ga Adang Bay fishing community.

She married young to a fisherman named Tete.

Their daughter Akosa was born in 1895.

Amma was known for skill in traditional cloth dying and her strong voice.

She often led songs during community ceremonies.

In late 1896, British colonial agents working with local intermediaries came to coastal villages, recruiting people for a cultural exposition in America.

They promised good wages, claimed the visit would last only 6 months, and presented it as an opportunity to serve as cultural ambassadors.

Agents specifically sought families with young children, saying it would make displays more authentic.

Ted was suspicious and refused.

But agents were persistent and offered what seemed enormous.

Enough money to support extended family for years.

Under pressure from family members seeing financial opportunity and reassured by other community members also going, Amma eventually agreed.

She left Teshi in January 1897 with a Koswa not yet 2 years old.

She was among 24 people from various Gold Coast communities who boarded the Providence.

They were told they would return by year’s end with promised payment.

She never came back wrote.

Tete waited for years.

He sent inquiries through colonial administrators, missionaries, anyone who might help.

No one could tell him what happened.

Eventually, he was told they probably died of disease in America.

He remarried in 1902, but kept Amma’s wedding cloth for the rest of his life, hoping she might return.

This was confirmation they needed.

The woman in the photograph was Amma Oderee from Teshi.

The child was her daughter, Akosua.

They hadn’t been willing participants in cultural exchange.

They had been deceived by recruitment agents working with traffickers, brought to America under false pretenses and exhibited in a cage.

Marcus found Amma and Aosua in Bradford’s final accounting records, though not by name.

After the exposition closed December 31st, 1897, Bradford was responsible for arranging return passage.

His records showed he booked space on a ship departing Charleston January 20th, 1898 for 18 natives returning to Gold Coast.

18.

He brought 24, but only 18 were going home.

Records noted three deceased during exhibition period.

Consumption, fever, exposure.

Three children placed with local families by arrangement with exposition committee.

Akosua was separated from Amma, Lauren realized with horror.

They took the child.

That’s why only 18 returned.

But this raised an agonizing question.

Had Amma been among the 18 who returned or one of the three who died? Records didn’t specify individuals.

Marcus spent weeks searching Atlanta city records, church archives, and newspaper announcements from late 1897 and early 1898, looking for mentions of African children placed with local families.

What he found confirmed worst fears and revealed systematic cultural destruction.

The Atlantic Constitution ran a notice December 28th, 1897, days before the exposition closed.

Several young children from the Ethnological Congress will be available for Christian adoption to suitable families.

These unfortunate infants whose parents are unable to care for them will benefit greatly from proper American upbringing.

The language was deliberately misleading.

Unable to care for them implied neglect rather than forced separation.

And Christian adoption suggested charity rather than cultural kidnapping.

Cross-referencing notices with census records and city directories, Marcus identified three Atlanta families who suddenly had adopted black children of African origin between 1897 and 1900.

One family stood out.

Jonathan and Martha Prescott, a wealthy merchant family.

The 1900 census listed them with a ward named Sarah, age approximately five, born in Africa.

If Akosa was about two in 1897, she would be about five in 1900.

The timing matched perfectly.

Patricia found more evidence in church records.

First Presbyterian church records from January 1898 included a baptism entry.

Sarah, ward of Jonathan and Martha Prescott, age estimated three years native of Africa, received into Christian faith.

The casual eraser was documented.

Akosua’s name replaced, her identity stripped, her connection to her mother severed and replaced with Christian baptism.

Martha Prescott had written to her sister about the adoption.

Patricia found the letter.

We have taken in a little native girl from the exposition.

She is quite young and speaks only savage gibberish.

We have named her Sarah and will raise her as a Christian servant.

Jonathan thinks we are performing great charitable service.

The cruelty was casual and unexamined.

Akosua’s G language dismissed as gibberish.

Her future predetermined as servitude, her forced separation framed as charitable rescue.

This was cultural genocide disguised as Christian benevolence.

The most painful discovery came when Marcus found Bradford’s complete accounting.

January 10th, 1898.

Entry read, 18 natives departed Charleston for return passage to Gold Coast.

Advanced payment received, children separated for arrangement.

No further responsibility.

Marcus cross referenced this with the return voyage manifest.

The vessel departing Charleston January 20th, 1898 listed 18 African natives formerly of Bradford Ethnological Exhibition buried in the detailed manifest listing approximate ages and genders was an entry.

Female approximately 26 years Gold Coast origin.

Amma had been among the 18 who returned.

She had survived the exhibition, survived months of being caged and displayed and dehumanized, but she had been forced to leave her daughter behind.

Bradford and exposition organizers separated Aosua from her mother before putting Amma on that ship back to Africa.

The team sat in devastated silence.

Amma had endured everything.

The deceptive recruitment, the Atlantic crossing, the confinement, the three and a half months of exhibition, the deaths around her, the constant dehumanization, only to have her daughter stolen just before she could return home.

She must have fought, doctor said quietly.

She must have screamed, resisted with everything she had, and they took Akosa.

Anyway, the team now faced two parallel investigations.

Tracing what happened to Amma after returning to Teshi in 1898, and tracking Aoswa’s descendants through the Prescott family line in America.

In Ghana,Wame worked with extended family and community historians to piece together what happened when Amma returned.

Oral history was fragmentaryary and painful.

Amma arrived back in Acra in February 1898.

Alone, devastated.

She returned to Tete and tried to explain what happened.

The deception, the exhibition, the separation from Aosua.

Tete believed her, but the trauma was overwhelming for both.

They tried to get help, filing complaints with British colonial administrators, seeking assistance from missionaries, begging anyone with authority to help find their daughter.

No one helped.

Colonial administrators said they had no jurisdiction over American affairs.

Missionaries offered only prayers.

According to family stories, Amma never fully recovered.

She lived with profound grief and guilt despite having done nothing wrong.

She had two more children with Teta, but spoke often of the daughter who had been taken.

She died in 1924 at age 52, not old, but worn down by decades of carrying unbearable loss.

Her descendants are here.

Wami wrote, “Tete and Amma’s later children had families.

I am descended from their son born in 1902.

There are dozens of us.

We all grew up hearing the story of Aunt Kosua who was lost in America.

We never thought we would find proof, never thought we would see her face.

And now you have sent us this photograph.

In America, Patricia and Marcus traced Aosa’s life through the Prescott family and beyond.

Census records showed Sarah living with the Prescotts through 1900, 1910, and 1920.

Always listed as servant or ward, never as family.

No indication she received formal education beyond basic literacy.

In 1921, city records showed Sarah Prescott marrying Thomas Wright, a railroad porter.

The marriage certificate listed her race as colored, parents as unknown, birthplace as Africa.

She was 26.

The age of Kosa would have been, and apparently had no memory or knowledge of her real name, her mother, or her home.

Her entire identity had been erased.

The 2-year-old, taken from Amma, had grown up as Sarah with no knowledge of being a Kosua.

No memory of her mother or Ga language or heritage.

The cultural genocide had been complete.

But Sarah survived and she had children.

Patricia traced three daughters born between 1922 and 1928.

Ruth, Clara, and Dorothy.

Those daughters married, had children, and those children had children through the generations.

Working with genealogologist Jennifer Blake, they traced the family tree forward to present day.

The search identified 47 living descendants of Aoshua, ranging from elderly great grandchildren to young great great grandchildren scattered across Georgia, North Carolina, Florida, and Texas.

None knew their true heritage.

They knew grandmother or great-grandmother Sarah had been from Africa, but no details beyond that.

They had no idea about Amma, about Teshi, about the Gaadong Bay people, about the human zoo exhibition, or about the forced separation.

The team decided to start with the eldest living descendant, Dorothy Wright’s daughter, Janet Thompson, aged 73, living in suburban Atlanta.

When Marcus called and carefully explained they had discovered information about her grandmother Sarah’s origins, Janet agreed immediately to meet.

I’ve always wondered.

Grandma never talked about her childhood.

Maybe now I’ll finally understand.

Marcus and Lauren traveled to Atlanta to meet Janet Thompson, carrying copies of photographs, historical documents, and research connecting her grandmother Sarah to Amma Odardi and Aosua.

They met at Janet’s home on a cold afternoon in January 225.

Janet welcomed the warmly, though her expression showed both curiosity and concern.

She was a retired teacher, dignified and sharp-minded, who had spent years researching her family history, but never traced back further than her grandmother, Sarah.

Please tell me what you found.

Marcus and Lauren spent two hours walking Janet through the discovery step by step.

They started gently, showing the photograph of Amma holding a kosa and explaining how it had been found.

They described what initial examination revealed.

The fence, the watching crowd, the admission sign.

Janet’s expression shifted from interest to confusion to growing horror as they explained what human zoos were, how they operated, and how her grandmother had been exhibited in one.

Wait, are you telling me my grandmother was displayed in a cage like an animal in Atlanta? Yes, Lauren said gently but directly.

The woman holding the child is Amma Odi.

The child is her daughter, Akoswa.

Your grandmother, who was later renamed Sarah by the family that took her.

They showed the documentation.

Bradford’s trafficking records, shipping manifests, exhibition photographs, newspaper notices about adopting children, Prescott family records, every piece of evidence proving this wasn’t speculation, but documented fact.

Janet’s hands trembled as she examined the photographs.

She looked at Amma’s face, at the protective way she held Aosua, at the hand gesture frozen in time.

My grandmother was stolen.

She was kidnapped from her mother and her whole identity was erased and we never knew.

Four generations and we never knew.

Marcus shared information from Ghana aboutqwame and the oral histories about Tete and Amma’s life before trafficking about how Amma returned to Teshi without her daughter and lived with that grief the rest of her life.

He explained that Janet had relatives in Ghana, descendants of Amma and Tete’s later children, people who had kept Akosua’s memory alive.

I have family in Ghana after 127 years.

There are people who remember.

Lauren showed more photographs from Robert Chandler’s collection.

Other images of the exhibition of Amma standing alone of the constructed village with its fence and watching crowds.

Your great great grandmother wanted to be remembered.

This hand gesture she’s making, it means do not forget in gay culture.

She was sending a message across time, hoping someone would eventually see it and understand.

They sat together for a long time, Janet crying quietly as she processed what she had learned.

Finally, she asked, “What happens now,” Marcus explained they had identified 47 other descendants.

“You’re not alone in this.

There’s an entire extended family that shares this history.

And there are relatives in Ghana who want to connect, who want you to know about Amma and your G heritage.

” Janet looked at the photograph again at Amma’s direct gaze.

She’s looking right at us, isn’t she? Right through 128 years, making sure we know what happened.

making sure we don’t forget.

Yes, she refused to be erased.

And now neither will Aosua.

Over the next month, the team helped Janet connect with other descendants, carefully explaining the discovery to each one.

Gradually, a community formed among these dispersed descendants, united by their connection to Amma and Akosua.

Preparing to share Amma’s story with the public required careful deliberation, the team, the descendants, and an advisory committee spent weeks discussing ethical implications and the best approach.

Janet insisted the story be told comprehensively.

This can’t be sugarcoated.

People need to understand that human zoos were real, operated openly with institutional support, and real people with names and families were trafficked and exhibited.

Amma’s story needs to be told, but so does the larger truth.

In February 2825, the Smithsonian held a press conference that drew international attention.

The room was packed with journalists, historians, and community members.

Janet and other descendants sat in the front row alongsidewame who had flown from Ghana.

Behind them projected on screens was the photograph of Amma holding a Koswa.

Lauren presented the discovery and investigation walking the audience through how routine archival work had revealed hidden horror.

She showed the original photograph then magnified details revealing the fence crowds admission sign.

She explained what human zoos were and how widespread they had been.

Marcus presented Amma’s story specifically.

Her life in Teshi, the deceptive recruitment, the Atlantic crossing, the months of exhibition, and the devastating separation from Aosua.

He showed documentation proving every element.

Amma Oderte was trafficked, exhibited, and had her child stolen.

This was a crime committed openly and celebrated publicly.

But the most powerful moment came when Janet stood to speak.

She held a recent photograph showing multiple generations of Akosa’s descendants.

This is what they tried to destroy but couldn’t.

Akosua survived.

She had children despite everything.

And now we know where we come from.

We know Amma’s name.

We know about Teshi and the Ga people and our true heritage.

She turned to look at Amma’s image on the screen.

My great great grandmother made that hand gesture.

Do not forget and we won’t.

We will remember.

We will make sure America remembers what was done in the name of entertainment and education.

The story spread rapidly.

Within days, it was international news.

The photograph appeared everywhere, accompanied by headlines about America’s forgotten shame.

Public response was intense.

Many shocked to learn human zoos had existed, others sharing family stories.

Museums and archives across America began re-examining their collections for similar photographs and documentation.

Several institutions discovered their own connections to human zoos and began difficult work of acknowledgement and historical reckoning.

The Smithsonian opened a permanent exhibition titled Caged the Truth About Human Zoos in America 1870 1940.

HMA’s photograph was displayed prominently along with documentation of other identified victims and comprehensive historical context.

Educational curricula were revised nationwide to include this history.

Students learned about human zoos as part of understanding racism’s institutional manifestations.

Ama’s photograph became one of the era’s most recognized images, not for shock value, but because her direct gaze demanded viewers acknowledge her humanity and the injustice done to her.

Four months after going public, an extraordinary event occurred.

American and Ganaian descendants organized a ceremony in Teshi to symbolically bring Amma home.

Janet and 15 other descendants traveled to Ghana, bringing highquality prints of all photographs and soil from the site where the Atlanta Exposition had been held.

The journey was funded partly through a documentary being produced, partly through crowdfunding from people moved by Amma’s story.

The village of Teshi welcomed them with elaborate ceremony.

Hundreds gathered, descendants from both sides of the Atlantic, community elders, and people moved by the story.

A shrine was prepared with Amma’s photographs, traditional GA textiles, and offerings of food and drink.

Na Odarte, now the family’s eldest member in Ghana, led the ceremony.

Through a translator, she spoke about the importance of memory and the power of names.

For 128 years, Amma has been lost to us.

Not lost in our hearts, but lost from her home.

Lost from proper burial, lost from the acknowledgement she deserved.

Today, we bring her home.

Today, we say her name and remember her strength.

Or the ceremony included traditional GA music, prayers in the gay language, and pouring of libations.

Each American descendant was invited to speak and pour water onto the shrine, connecting them to their ancestor and the land she had come from.

Janet spoke for many.

I came here not knowing who I was, not fully.

My grandmother Akosa was given the name and Sarah and told she had no history, but that was a lie.

We have a history.

We have a homeland.

We have family.

Amma, your great great granddaughter has come home to honor you.

The emotional weight overwhelmed many attendees.

Descendants from both sides of the Atlantic embraced, connected by blood and by the story of a woman who had refused to be erased.

children present, great great great grandchildren of Amma played together, speaking different languages but sharing DNA and heritage.

The ceremony concluded with burial of a small memorial containing copies of Amma’s photographs, letters written by descendants and the soil from Atlanta.

A stone marker was erected.

Amma Oderte 1872 1924 daughter of Teshi, mother of Aoswa.

Stolen but not forgotten.

Caged but not broken.

Your family remembers.

In the months following, Amma’s story catalyzed broader reckonings.

Descendants of other human zoo victims formed organizations demanding institutional accountability and support for genealological research.

Cities where exhibitions had been held erected memorials.

On the anniversary of the Atlanta Exposition, Georgia’s governor issued a formal apology.

On behalf of the state of Georgia, I apologize for our state’s role in the dehumanization and exhibition of Amma Odarti, Akosa Odarti, and all those trafficked and displayed.

We acknowledge this was a crime against humanity celebrated by our institutions and its legacy of racism continues to impact communities today.

A memorial was unveiled in Atlanta’s Piedmont Park.

A bronze sculpture of a woman holding a child.

Her hand raised in the God gesture meaning do not forget.

Around the base were engraved the names of all documented people exhibited in Atlanta in 1897.

Lauren often returned to see Amma’s photograph in the Smithsonian’s permanent collection.

It had been reframed and repositioned, no longer in storage, but displayed prominently with full context.

Amma’s real name and information about her life and legacy.

When I first saw this photograph, Lauren reflected.

I saw a mystery to be solved.

Now I see Amma, a real woman with a name, a history, a family, and a message she was determined to send across time.

She wanted to be remembered, and now she is.

The photograph had become evidence, testimony, memory, and resistance.

Ama’s gaze continued challenging viewers, refusing to let them turn away, insisting they acknowledge what had been done.

And in Teshi, children grew up learning Amma’s story, not as tragedy alone, but as testament to their ancestors strength.

They learned the old God gesture, understanding that even in darkness, their people had found ways to communicate, to resist, and to ensure their stories would survive.

Amma Oderte had asked not to be forgotten.

128 years later, she never would

News

📜 POPE LEO XIV UNSEALS A FORBIDDEN SCROLL FROM THE VATICAN VAULTS — CLAIMS IT REVEALS CHRIST’S “FINAL COMMANDMENT” HIDDEN FOR 2,000 YEARS, AND NOW CARDINALS ARE SCRAMBLING TO EXPLAIN THE SILENCE 🕯️ In a candlelit archive beneath St. Peter’s, the pontiff allegedly unveiled brittle parchment that insiders say could rewrite everything believers thought they knew, sparking whispers of cover-ups, shattered dogma, and a Church terrified of its own past 👇

The Revelation of the Hidden Scroll: A Journey into Darkness In the heart of the Vatican, a storm was brewing….

💥 15 NEW REFORMS SHAKE THE VATICAN — POPE LEO XIV DROPS A HOLY HAMMER ON CENTURIES OF TRADITION, CARDINALS STUNNED, DOORS SLAMMED, AND WHISPERS OF “SCHISM” ECHO THROUGH ST. PETER’S 🔔 In a move insiders call “the most explosive shake-up since the Middle Ages,” the new pontiff reportedly blindsided bishops at dawn with sweeping decrees that rewrite worship, power, and money itself, leaving the marble halls trembling and the faithful wondering who’s really in charge now 👇

The Awakening of Faith: A Shocking Revelation In a world where faith was a flickering candle, struggling against the winds…

It was just a photo of two sisters — but it hid a dark secret

It was just a photo of two sisters, but it hid a dark secret. The photograph appeared ordinary at first…

It Was Just a Portrait of a Mother and Her Children — But When Experts Zoomed In, They Paled

It was just a portrait of a mother and her children. But when experts zoomed in, they pald. Rebecca Turner…

It was just a photo of a girl with flowers — until you notice what she’s hiding in her hand

It was just a photo of a girl with flowers, but what she’s holding in her hand tells a different…

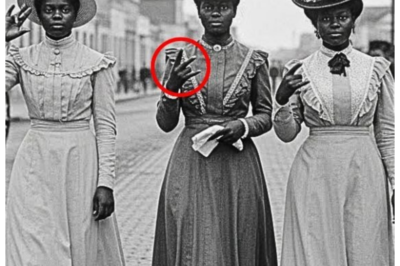

It was just a photo of three friends — until researchers deciphered the hand signal they were making

It was just a photo of three friends until researchers deciphered the hand signal they were making. The New Orleans…

End of content

No more pages to load