It was just a photo of a mother and child until you saw the symbol hidden in her fingers.

Dr.Maya Richardson adjusted the archival lamp at the Atlanta History Center, illuminating the photograph she had been examining for the past 20 minutes.

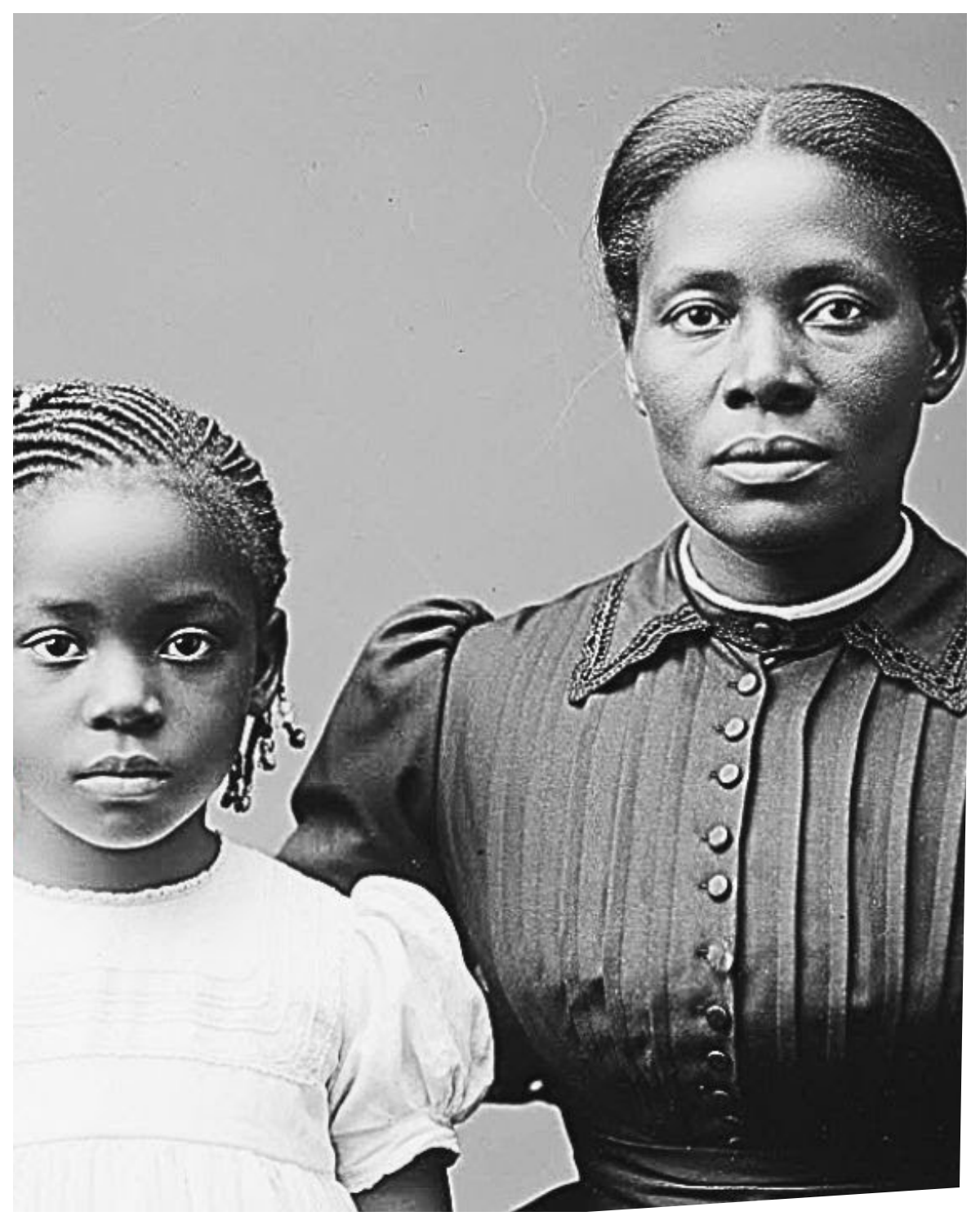

The image showed a black woman, perhaps in her late 30s, seated with a young girl of about seven standing beside her.

The photograph was dated 1901 on the back, taken in what appeared to be a simple photography studio with a plain backdrop.

At first glance, it seemed like a typical portrait from the turn of the century.

a mother and daughter dressed in their Sunday best, posing formally for what was likely an expensive and rare photograph.

But Maya had learned during her 15 years as a medical historian specializing in African-American healing practices, that photographs from this era often contained hidden meanings, subtle acts of resistance captured in seemingly ordinary images.

What caught Maya’s attention was the woman’s left hand, which rested on her daughter’s shoulder.

The positioning seemed natural enough, but the configuration of her fingers was unusual.

Her thumb and middle finger touched at the tips while her index finger extended slightly upward and her remaining fingers curved inward.

It wasn’t a random placement.

The gesture was too deliberate, too specific.

Maya had seen similar hand positions before in her research on West African spiritual and healing practices.

She pulled out her reference materials on Yorba, Igbo, and Aken symbolic gestures.

After cross- referencing several texts, she found what she was looking for.

The hand position matched a traditional healing symbol used by practitioners in multiple West African cultures, representing protection, spiritual power, and the transmission of ancestral knowledge.

She turned the photograph over carefully, written in faded pencil.

Mama Esther and daughter Grace, Atlanta, Georgia, June 1901.

The Lord is our strength.

Below that, in different handwriting, much fainter.

She knew.

Maya’s pulse quickened.

She knew, suggested the photographer or someone else had recognized the significance of the hand gesture.

This wasn’t just a family portrait.

It was a statement, a declaration of identity and purpose hidden in plain sight.

The photograph had arrived at the history center as part of a large donation from the estate of a woman named Ruth Morrison, who had died at 93.

Maya made a note to examine the rest of the donation carefully.

She suspected this photograph held a story that needed to be uncovered.

a story about resistance, healing, and the preservation of African knowledge in a society that sought to erase it.

Maya spent the following day working through the Morrison estate donation, searching for any information about the woman and child in the photograph.

In the fifth box, she found a leatherbound journal with Grace Morrison embossed on the cover.

The first entry was dated 1945.

I am writing this account now at age 51 because the stories must be preserved.

My mother, Esther Williams, died 10 years ago, taking with her knowledge that sustained our community for decades.

I was too young to understand the full scope of her work when I was a child.

But now I recognize what she was, what she risked to keep our people alive and healthy when white doctors would not treat us or treated us with contempt and cruelty.

Maya continued reading, her excitement growing.

The photograph taken in 1901 was my mother’s idea.

She insisted we have it made, though it cost money we could barely spare.

She wore her best dress and positioned me beside her.

And then she made that gesture with her hand, the healing sign her grandmother had taught her, passed down from Africa through generations of women in our family.

She wanted it documented, she said, in case something happened to her.

She wanted proof that our knowledge existed, that we existed.

Grace’s journal explained that Esther had been what the community called a rootwoman or granny healer, a traditional practitioner who used herbs, spiritual practices, and ancestral knowledge to treat illnesses, assist with childbirth, and provide care that the segregated medical system denied to black residents of Atlanta.

Maya found a second journal, this one much older and more fragile, with Esther Williams written inside the front cover.

The entries began in 1895, written in careful, practiced handwriting.

January 1895, delivered Mrs.

Patterson’s baby tonight.

The labor was long and difficult, but I used the herbs grandmother taught me.

Blahash to strengthen contractions.

Red raspberry leaf tea for the mother’s strength.

Mother and baby are well.

Mrs.

Patterson tried to pay me with the two pennies she had saved, but I refused.

Our people have so little.

The white doctors charge $5 for a delivery and will not even enter our neighborhoods.

I do this work because it must be done.

The entry continued with medical details, herbs used, preparation methods, spiritual prayers spoken during the birth.

Maya realized she was looking at a detailed record of traditional African-American healing practices from over a century ago, preserved by a woman who understood the importance of documentation, even as she practiced in secret.

Maya discovered that Esther had kept meticulous records of every patient she treated between 1895 and 1930.

The journals filled three boxes in the donation, each entry documenting symptoms, treatments, and outcomes with the precision of a trained physician, though Esther had never attended medical school and likely had limited formal education.

March 1896.

A young Thomas Green came to me with deep cough, fever, difficulty breathing.

His mother said the white doctor at the charity hospital examined him for 5 minutes, said it was negro consumption, and sent them away with no treatment.

I recognized pneumonia, prepared a steam tent with eucalyptus and pine, gave him tea made from mullen leaf and wild cherry bark, applied a mustard plaster to his chest, stayed with the family for three days and nights, monitoring his breathing.

The fever broke on the fourth day.

Thomas survived.

Entry after entry revealed the same pattern.

Black patients denied care or mistreated by white medical establishments, turning to Esther as their only option.

She treated everything from childhood illnesses to difficult births, from injuries to chronic conditions, using a combination of herbal medicine, spiritual healing, and practical nursing care.

But Maya also found evidence of the risks Esther faced.

A journal entry from 1899, the new health commissioner, Dr.

Bradford has declared that all unlicensed medical practitioners in Atlanta will be prosecuted.

He means us, the root women, the granny midwives, the healers who serve our people.

He calls us ignorant and dangerous.

Says we spread disease and superstition.

He does not mention that his licensed doctors refuse to treat negroes or that they experiment on us without consent or that they let our children die rather than dirty their hands touching black skin.

Maya found a newspaper clipping from the Atlanta Constitution dated November 1899.

city cracks down on unlicensed negro healers.

Health commissioner warns of dangers of folk medicine.

The article described Esther and other traditional practitioners as threats to public health calling their practices primitive and potentially deadly.

But tucked into the same journal page was a counternarrative, a letter from a white physician, Dr.

Samuel Foster, dated December 1899.

Dear Mrs.

Williams, I’m writing to warn you that Dr.

Dr.

Bradford intends to make an example of you by prosecuting you for practicing medicine without a license, I have observed your work from a distance, and though I cannot say so publicly, I recognize that you provide competent and compassionate care to a population that our medical establishment shamefully neglects.

Please be cautious, the law is not on your side.

Maya found a section in Esther’s earliest journal that explained where her knowledge came from.

The entries from 1895 described her grandmother, a woman named Abana.

Grandmother Abana passed away today at age 87.

She was born in 1808 before emancipation, before the war, in a time I could barely imagine.

She told me once that her own mother had been brought from Africa from a place she called the Gold Coast on a slave ship when she was a young woman.

That woman, my great-grandmother, whose name Abana said was Aoswa, had been a healer in her village, trained in the use of plants and spiritual practices to cure illness and protect the community.

Esther wrote that Akosua had preserved her knowledge through slavery, teaching it secretly to her daughter Abana, who in turn taught Esther.

Grandmother said that when she was a child, she would go into the woods with her mother to gather plants.

Her mother taught her which leaves stopped bleeding, which roots brought down fever, which bark eased pain.

She taught her the prayers to speak over the sick, the rituals to perform for difficult births, the ways to read the body’s signs to understand what was wrong.

All of this was forbidden.

Enslaved people were not supposed to have knowledge, especially not knowledge that came from Africa.

But grandmother’s mother taught her anyway because our people needed healing and the white doctors would not come.

Maya found detailed descriptions of specific remedies that had been passed down through four generations.

For fever, willow bark tea, feverfue leaves, cool cloths with lavender water.

For wounds, yrow to stop bleeding, comfrey to speed healing, honey to prevent infection.

For childirth, red raspberry leaf to strengthen the womb, blue cohos for contractions.

Mother wart for afterpanes, for grief of the spirit, prayers to the ancestors, laying on of hands, speaking the person’s true name, the African name, not the slave name, to remind them who they are.

Esther had added her own observations to this inherited knowledge, noting which treatments worked best for which conditions, recording new remedies she discovered through experimentation and observation.

She had essentially created a medical text documenting traditional African healing practices as they adapted and evolved in the American South.

Maya realized the hand gesture in the 1901 photograph represented this entire lineage from Akosua in West Africa through Abana who survived slavery to Esther who practiced during Jim Crow to Grace who witnessed and remembered.

The symbol in Esther’s fingers was a declaration.

This knowledge survives.

We survive and we will not be erased.

Maya discovered that Esther hadn’t worked alone.

Her journals revealed a network of black women healers across Atlanta and throughout Georgia, all practicing traditional medicine and supporting each other against increasing legal pressure.

April 1900, met with sisters Clara, Josephine, and Ruth today at the church.

We shared knowledge.

Clara has found a new preparation for CRO that seems to work better than what we’ve been using.

Josephine warned us that Dr.

Bradford sent inspectors to her neighborhood last week asking questions about who the colored folks go to for medical care.

We must be more cautious.

We agreed to use the old signals.

If someone needs a healer, they will tie a white cloth on their fence.

If there is danger, a red cloth.

The network had developed elaborate systems to protect themselves and serve their community.

Maya found references to coded language, safe houses where healers could practice without being observed, and warning systems to alert each other when authorities were investigating.

But the journals also revealed the toll this constant vigilance took.

June 1900.

I am exhausted, not from the work, but from the fear.

Every knock on the door might be the police.

Every white stranger in the neighborhood might be an inspector.

I delivered three babies this month, treated a dozen children for summer fever, set a broken arm, prepared herbs for five families, all of it illegal according to the new city ordinances.

If I am caught, I will be fined, possibly jailed.

But if I stop, who will care for our people? Maya found evidence that the persecution intensified after the 1906 Atlanta race riot, a journal entry from September 1906.

The city is still burning, though the worst violence has passed.

Dozens of our people were killed by white mobs.

Many more were injured, shot, beaten, stabbed.

I worked for 4 days straight treating the wounded in secret because the white hospitals would not admit negroes, and the colored hospital was overwhelmed.

I saw wounds I had never seen before, gunshots, terrible burns, injuries from beatings.

I did what I could with the knowledge grandmother gave me, but it was not enough.

Some died in my arms.

Now, doctor Bradford says the riot proves that negroes need proper medical supervision and has called for stricter enforcement of licensing laws.

He does not mention that his licensed doctors stood by while our people bled to death in the streets.

He wants to eliminate us, the healers who actually serve the community that our people will have nowhere to turn except to white institutions that despise us.

Maya found the entry in Esther’s journal that explained why the photograph had been taken in June 1901.

Grace is 7 years old now, old enough to begin learning the healing work if she chooses.

I took her to have our photograph made because I wanted to mark this moment.

The point where she could begin to carry the knowledge forward as grandmother taught me, as her mother taught her back to the ancestors in Africa.

I made the healing sign with my hand.

The symbol grandmother showed me.

The one her mother used, the one that connects us to our people across the ocean and across time.

I wanted grace to see it in the photograph, to remember that this knowledge is precious and powerful, that it must be protected and passed on.

And I wanted evidence in case I am arrested or killed for this work that I existed, that I served my people with honor, that I carried the ancestors wisdom.

” The entry continued with instructions Esther had given the photographer, a black man named Isaiah Thompson, who operated a small studio in the Auburn Avenue neighborhood.

Mr.

Thompson understood immediately what I was asking.

He said, “Sister Esther, I know what you do for our people.

I will make sure this photograph shows your truth.

” He positioned us carefully, made sure the light would capture my hand clearly, and took several exposures to ensure we would have a good image.

When I paid him, he said, “There’s no charge for documenting our history.

I insisted on paying anyway, $2, money I could barely spare, but worth every penny.

” Maya found a later entry explaining the notation she knew on the back of the photograph.

Mr.

Thompson wrote that note himself when he gave me the finished photograph.

He said that his own grandmother had been a healer, that he recognized the symbol in my hand.

She knew, he wrote, meaning his grandmother knew the old ways, the African ways, just as I know them, just as Grace will know them if she chooses this path.

It was his way of saying, “You’re not alone.

Your work is seen and valued, and your knowledge will survive.

” Grace’s journal from 1945 added more context.

I remember the day that photograph was taken.

Mama made me wear my best dress and brush my hair for an hour.

She seemed nervous, which was unusual.

Mama was never nervous.

In the studio, she positioned me just so, then placed her hand on my shoulder in that special way.

Later, she explained what the gesture meant, how it connected us to our ancestors, how it represented the healing work she did.

She said, “Grace, remember this day.

Remember that our knowledge is powerful and must be protected.

” Maya found entries in Grace’s journal describing her complicated relationship with her mother’s work and the choice she faced as she grew older.

1912.

I am 18 now and mama wants me to begin training seriously as a healer.

She’s been teaching me herbs and remedies since I was a child.

But now she wants me to assist with births to treat patients on my own to carry forward the work.

But I am afraid.

I have watched her live in constant fear of arrest.

I have seen how white authorities treat her with contempt and suspicion.

I have watched her work herself to exhaustion for people who can rarely pay her.

There’s a new negro college in Atlanta now, Spellelman, that trains colored women to be teachers and nurses.

If I could go there, I could learn modern medicine, get a real license, practice legally.

Mama says that the schools teach white man’s medicine, that they will not respect the African knowledge, that they will try to make me forget where I come from.

But wouldn’t it be better to have both the old knowledge and the new credentials? Why, I have found evidence of the tension this created between mother and daughter.

An entry from Esther’s journal in 1913.

Grace told me today that she has applied to the nursing program at Spellman.

She says she wants to be a real nurse, licensed and recognized.

I felt as though she had struck me.

Is what I do not real? Is the knowledge that has sustained our people for generations not legitimate because white institutions do not recognize it? I know she means well, that she wants a safer path than the one I have walked, but I fear she will lose the old ways in pursuit of white approval.

But Grace’s journal revealed her more nuanced thinking.

1914.

I started at Spellman last fall.

The nursing instructors teach anatomy, physiology, germ theory, surgical technique, all valuable knowledge.

But they dismiss anything they call folk medicine as ignorant superstition.

And when I mentioned that my mother uses willow bark for fever, the instructor laughed and said, “Such remedies are placeos at best, dangerous at worst.

” She did not know that white doctors now use aspirin, which is derived from the same compound found in willow bark.

Mama’s superstition and their science are sometimes the same thing, just with different names.

I have decided that I will learn everything they teach me, earn my license, and then combine it with what mama taught me.

I will serve our community as a licensed nurse, which will give me legal protection Mama never had.

But I will also use the remedies and spiritual practices that I know work because I have seen them work my entire life.

Maya found documentation of increased persecution of traditional healers in the 1910s and 1920s.

Newspaper clippings showed a campaign by white medical authorities to eliminate what they called unlicensed negro practitioners.

Atlanta Journal, March 1915.

Health Department raids illegal medical operation.

Negro woman arrested for practicing medicine without license.

The article described the arrest of a woman named Clara Johnson, one of Esther’s network sisters, for delivering a baby.

She was fined $50, an impossible sum, and threatened with jail if caught again.

Esther’s journal entry from the same week.

They arrested Clara yesterday.

She had been a midwife for 30 years, delivered hundreds of healthy babies, never lost a mother.

But because she does not have the license that they will not give to colored women, she is now a criminal.

The mother whose baby she delivered testified in her defense, explaining that the White Hospital would not admit her, that Clara saved both her life and her baby’s life.

The judge did not care.

He said the law is the law.

Maya found evidence that Esther herself was arrested in 1918.

November 1918.

The influenza is everywhere, killing hundreds.

I have been working day and night treating the sick with fever reducers, steam treatments, herbs to support breathing.

Yesterday, a health inspector came to the house where I was treating a family.

He said I was practicing medicine illegally and arrested me.

I was taken to the police station, fingerprinted like a common criminal and charged with violating medical licensing laws.

Grace, now a licensed nurse, had to come pay my bail.

$5 I did not have.

But the arrest record Maya found told a more complex story.

Attached to Esther’s arrest file was a petition signed by over 200 black residents of Atlanta.

We, the undersigned, attest that Esther Williams is a skilled and compassionate healer who has served our community faithfully for over 20 years.

During the current influenza epidemic, she has worked tirelessly to care for the sick, asking nothing in return, while the hospitals and licensed physicians refuse to treat colored patients or charge fees we cannot afford.

We respectfully request that the charges against her be dismissed and that she be permitted to continue her essential work.

The judge had dismissed the charges, but with a warning that any future violation would result in jail time.

Esther’s journal entry after the dismissal.

I am free for now, but for how long? They want to eliminate us, to force our people to depend entirely on a medical system that does not serve us, that experiments on us, that lets us die rather than treat us with dignity.

I will continue the work as long as I am able, but I fear for what will happen when my generation of healers is gone.

Maya discovered that despite the persecution, Esther had found ways to preserve and transmit her knowledge.

In the donation boxes, she found teaching materials Esther had created, handdrawn illustrations of medicinal plants, written recipes for remedies, and detailed instructions for spiritual healing practices.

Most remarkably, Maya found a manuscript titled The Healing Book of Esther Williams: Traditional Remedies for Common Ailments Compiled for Future Generations.

The introduction, dated 1925, explained its purpose.

I’m writing this book because the knowledge must survive.

I am 60 years old now, and I have been a healer for 30 years.

I have seen many of the old healers pass away taking their knowledge with them.

The young people are taught in schools that our ways are primitive and worthless.

That only white doctor’s medicine is real medicine.

But I know the truth.

Our remedies work because they are based on generations of careful observation and experience passed down from the ancestors who brought this knowledge from Africa.

The manuscript contained over 300 pages of detailed medical information for pneumonia.

Create a steam tent using a large pot of boiling water with eucalyptus leaves, pine needles, and peppermint.

Have the patient breathe the steam for 15 minutes three times daily.

Prepare tea from mullen leaves, wild cherry bark, and whound, one cup every four hours.

Apply a mustard plaster to the chest before sleep.

Monitor breathing closely.

If breathing becomes severely labored, seek additional help immediately.

Each remedy included not only the ingredients and preparation method, but also explanations of why it worked, observations about what conditions it treated best, and warnings about when professional medical intervention was necessary.

Esther had essentially written a medical textbook based on traditional African-American healing practices.

Maya found a letter from Grace attached to the manuscript dated 1935.

Mama died last week at age 70.

She worked until 3 days before her death treating a young mother with child bed fever.

The treatment worked.

The mother survived.

But mama was exhausted and her heart gave out.

She died as she lived in service to our people.

This manuscript represents her life’s work and the knowledge of four generations of healers in our family.

I am preserving it not only as a record of what Mama knew, but as proof that African healing knowledge is sophisticated, effective, and deserving of respect.

Grace had added her own notes to the manuscript, combining Esther’s traditional remedies with modern medical knowledge she had learned in nursing school.

Mama’s remedy for fever using willow bark works because willow contains salicin which the body converts to salicylic acid, the same active ingredient in aspirin.

Her use of honey on wounds prevents infection because honey has natural antibacterial properties, which modern science has now confirmed.

The steam treatments she used for respiratory illness are now standard practice in hospitals.

Our ancestors understood medicine in ways that white doctors are only beginning to recognize.

Maya stood in the Atlanta History C Center’s exhibition hall, looking at the display she had created over six months of research.

The centerpiece was the 1901 photograph of Esther and Grace with Esther’s hand position prominently visible and clearly labeled as a traditional African healing symbol representing protection, spiritual power, and the transmission of ancestral knowledge.

Surrounding the photograph were excerpts from Esther’s journals and healing manuscript, documentation of the persecution she faced, testimonials from community members she had helped, and Grace’s nursing credentials alongside her mother’s traditional remedies.

The exhibition was titled The Healing Hand: How African-American Women Preserved Medical Knowledge through Generations of Resistance.

But Maya had done more than create a historical exhibition.

Working with the Morehouse School of Medicine and several traditional healers still practicing in Atlanta, she had organized a symposium on integrating traditional African healing practices with modern medicine.

The event brought together physicians, nurses, herbalists, and community healers to discuss how traditional knowledge could complement contemporary healthcare, especially in underserved black communities.

On opening night, Maya watched as visitors studied the photograph of Esther and Grace.

An elderly woman approached, tears streaming down her face.

My grandmother was a root woman, she said quietly.

She delivered babies, treated fevers, set bones.

The white doctors tried to shut her down, but the community protected her because we needed her.

I never knew there were others like her, that there was a whole network.

A young black medical student stood before Esther’s healing manuscript, reading the detailed remedies.

“This is sophisticated medicine,” she said to her companion.

“Look at how she documented symptoms, treatments, and outcomes.

She was doing evidence-based practice before the term even existed.

Why didn’t they teach us this in medical school? I approached them and explained because the medical establishment wanted to eliminate traditional practitioners.

They had to label their knowledge as ignorant and dangerous.

They couldn’t acknowledge that these women were skilled healers because that would undermine the justification for arresting them and shutting them down.

So, they erased this history, pretended it never existed or never had value.

The exhibition included a modern component showing how some of Esther’s remedies had been validated by contemporary research.

Willow bark for pain and fever, now aspirin.

Honey for wound care, now recognized as antibacterial.

Various plant-based remedies, now studied as potential treatments for diabetes, hypertension, and other chronic conditions.

Grace’s granddaughter, now a retired physician in her 70s, attended the opening.

She brought with her the original healing manuscript in the 1901 photograph, which she donated to the history cent’s permanent collection.

“My grandmother, Grace, became a nurse, and my mother became a teacher,” she explained to the gathered crowd.

I became a doctor, but we all carried forward what Esther started, a commitment to healing our community and preserving the knowledge of our ancestors.

That photograph, she continued, pointing to the image of Esther and seven-year-old Grace, was taken at a pivotal moment.

Esther was facing increasing persecution for her healing work.

She knew she might be arrested or worse.

But she wanted to document her truth to show that African knowledge had value and power to pass that knowledge to her daughter and through her to future generations.

The symbol in her hand, that gesture connecting her to ancestors in Africa, was an act of resistance and hope.

That evening, Maya returned to her office and wrote a final entry in her research journal.

Esther Williams was a traditional healer who served Atlanta’s black community from 1895 until her death in 1935.

She preserved African medical knowledge passed down through four generations.

From her great-g grandandmother, who was brought from the Gold Coast on a slave ship, through slavery, reconstruction, and Jim Crow.

She faced persecution, arrest, and the constant threat of prosecution for practicing medicine without a license.

A license the system would not give it to black women, regardless of their knowledge or skill.

Or worse, the 1901 photograph of Esther and her daughter Grace captured more than a family portrait.

Esther’s hand, positioned in a traditional African healing symbol, was a declaration that this knowledge exists, that it has value, and that it will survive despite all efforts to erase it.

Through her journals and healing manuscript, Esther created a medical text documenting remedies that have since been validated by modern science.

Through her daughter, granddaughter, and great-granddaughter, her legacy of healing continues.

The symbol hidden in Esther’s fingers represents the resilience of African knowledge.

The courage of black women who resisted erasure and the importance of recognizing that healing traditions dismissed as folk medicine often contain profound wisdom.

May her story remind us that medical knowledge comes in many forms, that cultural traditions deserve respect, and that the hands that were once forbidden to heal have always held power.

She closed the journal and turned off the light, leaving the exhibition in darkness.

But the image of Esther’s hand, fingers arranged in the ancient symbol of healing, would continue to speak to visitors, a reminder that knowledge passed through generations of resistance cannot be erased, and that every gesture of defiance, no matter how small, contributes to the survival of a people’s truth.

News

💥 SILICON STATE MELTDOWN — CALIFORNIA GOVERNOR EXPLODES AS MICROSOFT DATA CENTER SHUTDOWN THREATENS ECONOMIC COLLAPSE ⚡ The narrator’s voice drips with tension as blinking servers go dark, tech workers scramble, and Sacramento braces for an industrial earthquake, turning a corporate decision into a political nightmare no one saw coming 👇

The Shocking Fallout of Silicon Dreams In the heart of Silicon Valley, where innovation once thrived like a wildfire, the…

⏳ APOCALYPSE REVEALED — POPE LEO XIV UNCOVERS AN ANCIENT SCROLL WITH THE EXACT DATE OF THE SECOND COMING, AND THE WORLD GASPS 😱 The narrator whispers as candlelight flickers over dusty pages, cardinals exchange nervous glances, and the Vatican trembles under a secret so explosive it could ignite global frenzy overnight 👇

Shocking Revelation: The Scroll of Destiny In the heart of a bustling city, where the noise of life drowned out…

🚀 HORMUZ UNDER FIRE — 24 MISSILES BLAST TOWARD A U.S.

NAVY CARRIER, THEN SOMETHING UNIMAGINABLE HAPPENS ⚡ The narrator’s voice drips with tension as radar screens flare, sailors brace for impact, and missiles streak through the sky like fire from the gods, only for a jaw-dropping twist to leave commanders and crews alike questioning reality itself 👇

The Day the Sea Roared: A Carrier’s Reckoning Captain James Morgan stood on the bridge of the USS Valor, the…

💥 SILICON STATE SHOCK — CALIFORNIA GOVERNOR LOSING GRIP AS BANKING GIANTS PACK UP AND FLEE TO TEXAS, LEAVING ECONOMY IN CHAOS ⚡ The narrator’s voice drips with suspense as empty corporate towers, frantic aides, and boarded-up branches paint a picture of panic, hinting that what looks like a quiet corporate exodus is actually a financial earthquake shaking Sacramento to its core 👇

The Exodus: California’s Financial Apocalypse In the heart of California, a storm was brewing, one that would shake the very…

💥 FINANCIAL APOCALYPSE — THE 8 CITIES WHERE BANK FAILURES COULD SPARK CHAOS FIRST, AND NO ONE IS PREPARED FOR THE SHOCKWAVES ⚠️ The narrator’s voice drips with suspense as empty ATMs, shuttered lobbies, and late-night boardroom whispers paint a picture of impending doom, warning that ordinary citizens might be the first to feel the ripple of a meltdown the experts have been quietly bracing for 👇

The Fall of the Titans: A Financial Reckoning In the heart of San Francisco, the sun set behind the Golden…

🌊 DESCENT INTO MADNESS — EXPLORERS PLUNGE TO THE BOTTOM OF THE MARIANA TRENCH AND WITNESS SOMETHING NO ONE ON EARTH WAS MEANT TO SEE 😱 The narrator’s voice drops to a suspenseful whisper as cameras flicker in the crushing darkness, pressure creaking around their vessel, and strange, impossible shapes appear through the murky water, hinting at secrets the planet has hidden for millions of years 👇

The Abyss of Secrets Dr.Emily Carter stood at the edge of the vessel, her heart racing as the robotic submersible…

End of content

No more pages to load