Look Closer: The Mirror in This 1907 Studio Photo Holds a Terrifying Truth

[Music] The Maryland Historical Society’s photography archive smelled of old paper and preservation chemicals.

Thomas Rivera had spent 15 years cataloging Baltimore’s photographic history, handling thousands of glass plates and faded prints that documented the city’s past.

The Thornon Studio collection had arrived.

Three weeks ago, three boxes of immaculately preserved photographs from one of Baltimore’s premier portrait studios, operating from 1895 to 1920.

Thomas has been working through them methodically, recording details about each image, subjects, dates, locations, technical notes.

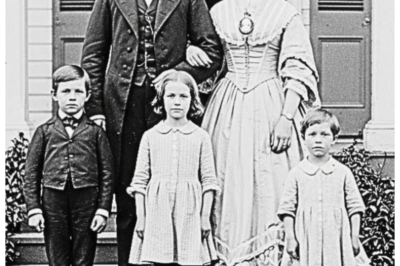

He removed another large format photograph from its protective sleeve, a formal family portrait, typical of the era.

The lighting was professional, the composition carefully arranged.

The photograph showed four people posed in an elegant studio setting.

Heavy velvet drapes framed the scene.

An ornate Barack mirror with an elaborate gilded frame hung prominently on the back wall, positioned slightly to the left at an unusual angle.

At the center stood a tall, distinguished man in his 40s, wearing a dark suit, his expression stern and authoritative.

Beside him sat a woman in an elaborate dress with leg of mutton sleeves, her hair styled in the Gibson girl fashion popular in the era.

Two boys flanked their parents, one about 12 years old, the other perhaps 10.

Both in formal dark suits with high collars, their postures rigid and uncomfortable.

A family of four, father, mother, two sons, all staring directly at the camera with the solemn expressions expected in formal Victorian portraiture.

Thomas was about to set the photograph aside when something caught his eye.

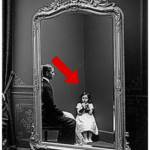

He leaned closer, adjusting his desk lamp, the mirror.

There was something in the mirror’s reflection.

He grabbed his magnifying loop and examined the reflected image carefully.

his breath caught in his throat.

In the mirror’s reflection, showing the reverse angle of the studio, there was a fifth person, a small figure, a child, standing far to the side of the studio space, completely outside the arranged family portrait.

The figure was barely visible in the shadows, but definitely there, a little girl, perhaps seven or eight years old, wearing a simple white dress that contrasted sharply with the elaborate clothing of the family members.

And she wasn’t posing.

She was standing alone, pressed against the wall, her small frame hunched as if trying to make herself invisible.

Thomas sat down the loop, his hands suddenly unsteady.

He looked at the main photograph again, four people, then back to the mirror.

Five people, the four-posed subjects, and one child who’d been deliberately excluded from the family portrait, a child who existed only in the reflection.

Thomas photographed the image with his high resolution camera and uploaded it to his computer.

He zoomed in on the mirror’s reflection, enhancing the detail as much as the century old photograph would allow.

The child in the reflection was clearer now.

She stood in the far corner of the studio outside the carefully lit area where the family posed.

Her white dress was plain, almost institutional, nothing like the ornate clothing worn by the mother and the elaborate suits on the boys.

Her posture told a story of fear.

She was pressed against the wall, her body turned slightly away as if trying to disappear into the shadows.

Her arms were visible, and Thomas could make out dark marks on them.

Bruises, he was certain.

Most disturbing was her face, even in the reflected image, even through the limitations of 1907 photography.

Her expression was unmistakable terror.

She was watching the family pose for their portrait, but she wasn’t part of it.

She’d been excluded, positioned where she wouldn’t appear in the photograph, relegated to existing only as an accidental reflection.

Thomas examined the photograph’s composition more carefully.

The mirror’s placement was highly unusual.

Most studio portraits from this era either excluded mirrors entirely or used them symmetrically for artistic effect.

This mirror was angled awkwardly, positioned in a way that broke traditional compositional rules.

It was positioned, Thomas realized, to capture that corner of the studio to document the child who’d been hidden.

He flipped the photograph over on the back in faded ink.

Thornton studio, Baltimore, October 1907, the Whitmore family.

Below that, in different smaller handwriting, four in the portrait, five in the room, Thomas felt a chill.

Someone, the photographer perhaps, had noted the discrepancy.

Someone had documented that a fifth person existed, even though she’d been deliberately excluded from the official family portrait.

He pulled up the studio’s business records.

October 1907, Whitmore family portrait.

The ledger notation read, “Standard family sitting, four subjects, special arrangement paid in advance, four subjects.

The child in the reflection didn’t count as a subject.

She was something else, someone hidden, someone who officially didn’t exist in the family’s photographic record.

Thomas needed to know who she was and why she’d been excluded.

Thomas spent the morning in the Maryland State Archives, searching for information about the Whitmore family.

They were easy to find.

Prominent in Baltimore Society, frequently mentioned in newspaper coverage of elite events, Edgar Whitmore, the father, had been a successful importer with offices near the harbor.

Married to Katherine Whitmore, N Ashford from an established Baltimore family.

The census records showed the family structure clearly.

100 census.

Edgar Whitmore, 35.

Katherine Whitmore, 32.

Robert Whitmore, five.

Henry Whitmore, three.

Alice Whitmore, one, Alice, there was a third child, a daughter.

But in the 1910 census, taken three years after the photograph.

Edgar Whitmore, 45.

Katherine Whitmore, 42.

Robert Whitmore, 15.

Henry Whitmore, 13.

No Alice, she disappeared from the records.

Thomas searched for death records and found what he was looking for.

and dreading a death certificate dated March 1908.

5 months after the photograph, Alice Whitmore, age 8, died March 12th, 1908.

Cause of death, injuries sustained in fall.

Attending physician, Dr.

Harrison Stewart.

A brief obituary in the Baltimore Sun confirmed it.

Alice Whitmore hate, daughter of Mr.

Edgar Whitmore, prominent importer, died yesterday following a tragic accident at the family residence on Mount Vernon Place.

Service is private.

The family requests no visitors during this time of grief.

No visitors.

a private service, a child who’d been excluded from the family portrait, then disappeared from the census records, then died in an accident at age 8.

Thomas found more troubling information in society page coverage of Whitmore family events between 1900 and 1907.

Alice was mentioned only twice.

Mr.

and Mrs.

Edgar Whitmore attended the autumn charity ball with their sons, Robert and Henry, 1905.

The Whitmore family, Mr.

Edgar, Mrs.

Catherine and their two fine boys were present at the mayor’s reception 1906.

Always their two fine boys, never their daughter.

In public records and social announcements and family photographs, Alice had been systematically erased, made invisible, except in that mirror.

That one reflection had captured what the family tried to hide.

A terrified child isolated and abused who officially didn’t exist.

Thomas returned to the Thornon Studio Records, focusing on the photographer who’d taken the Whitmore portrait.

The ledger showed that most work in October 1907 had been handled by the studio’s assistant, Frederick Chen.

Dot.

Thomas found Frederick’s employment record.

Hired in 1902, worked until 1915.

Noted for exceptional technical skill and innovative composition techniques.

He searched for more information about Frederick Chen.

Immigration records showed he’d arrived in Baltimore from San Francisco in 1900, age 18.

His father had been a photographer during the gold rush era, and Frederick had learned the trade from him.

Thomas discovered something significant.

Frederick Chen had been an authorized investigator for the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, a position he’d held since 1905.

He’d used his photography skills to document suspected abuse cases.

Thomas found newspaper articles about Frederick’s work.

In 1906, he testified in a child welfare case, using photographic evidence to prove mistreatment.

In 1909, his testimony had led to the conviction of a man who’d been beating his adopted daughter.

Frederick had been using photography deliberately strategically to document abuse that otherwise went unseen.

Thomas examined other photographs from the Thornton studio collection looking for patterns in Frederick’s work.

He found several portraits where mirrors were positioned at unusual angles capturing details that the main composition didn’t show.

A woman with bruises on her neck visible only in reflection.

A child with a black eye caught in a mirror when the family posed showing only their good sides.

Frederick had been creating a visual archive of hidden abuse, using mirrors to capture what families tried to conceal.

The Whitmore portrait fit perfectly into this pattern.

The family had requested a portrait of four people, deliberately excluding Alice.

Frederick had complied with their request for the main photograph, but he positioned a mirror to document the truth, that there was a fifth member of the family, a terrified child, isolated in the shadows, bearing visible signs of abuse.

He’d created two photographs in one.

The official image the family wanted and the evidence of what they were hiding.

But had anyone seen it? Had anyone acted on it? Thomas obtained access to the records of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children housed at the University of Baltimore Archives.

He found what he was looking for within hours.

Case 389 to W.

Whitmore Alice, age 8, October 1907.

The file contained Frederick Chen’s initial report.

filed October 25th, 1907, eight days after the family portrait session.

I photographed the Whitmore family at their request for a formal portrait.

They specified four subjects, parents and two sons.

However, a third child was present in the studio, a daughter approximately 8 years old, who was deliberately excluded from the portrait and kept in the corner of the room throughout the session.

The child appeared malnourished and frightened.

I observed extensive bruising on her arms and signs of recent injury on her face.

When I asked about her, Mr.

Dr.

Whitmore stated she was ill and not suitable for photography.

Mrs.

Whitmore said nothing.

I positioned a mirror to capture the child’s presence and condition.

I believe this child is in severe danger and request immediate investigation.

The report included a copy of the photograph, the same image Thomas had found.

The next document was an investigation report dated November 2nd, 1907.

Investigator Sarah Morrison visited the Whitmore residence on Mount Vernon Place.

Mr.

Whitmore stated that his daughter Alice is mentally deficient and prone to violent outbursts which necessitates keeping her separate from the family for her own safety and that of her brothers.

Mrs.

Whitmore confirmed this account.

She stated that Alice injures herself during her episodes which accounts for the bruising.

A family physician, Dr.

Harrison Stewart, provided a letter confirming Alice’s diagnosis of mental deficiency with self-injurious tendencies.

Alice was not produced for interview.

Mr.

Dr.

Whitmore stated she was having one of her episodes and was confined to her room for everyone’s protection.

Given the family’s prominence in the physician’s confirmation, no further immediate action recommended.

File marked for follow-up in 30 days.

Thomas’ jaw clenched.

The system had accepted the family’s explanation without even seeing the child.

A wealthy family’s word, backed by a compliant doctor, had been enough to close the investigation.

The follow-up report dated December 5th, 1907, was even more cursory.

A follow-up visit to Whitmore residence, Mr.

Dr.

Whitmore reports Alice’s condition unchanged.

Child again not produced, reportedly sedated due to violent episode earlier in the day.

Dr.

Stewart’s continued supervision noted no evidence of immediate danger to warrant further intervention.

Case monitoring continued.

A final entry dated March 15th, 1908.

Case closed.

Alice Whitmore deceased following accidental fall downstairs at family residence.

Death certificate signed by Dr.

Harrison Stewart lists cause as head trauma from fall.

No signs of foul play, noted.

Mr.

and Mrs.

Whitmore report the child had one of her episodes and fell while unsupervised.

File archived.

But there was one more document.

A handwritten note from Sarah Morrison dated March 18th, 1908.

I cannot accept this.

I visited that house twice and never once was allowed to see the child.

Now she’s dead and I’m supposed to believe it was an accident.

A child with violent episodes somehow fell downstairs while unsupervised.

Why was she unsupervised if she was so dangerous? I believe Alice Whitmore was murdered.

I believe her mental deficiency was a fabrication to justify her abuse and isolation.

I believe Dr.

Stewart conspired to cover this up.

But I have no proof, and the family’s word, backed by a physician, carries more weight than my suspicions.

We failed this child.

The system failed her, and she’s dead because we chose to believe a wealthy man’s lies over the evidence in front of us.

Thomas needed to understand Dr.

Harrison Stewart’s role in Alice’s death.

He found Steuart’s medical license records.

The doctor had been a respected Baltimore physician, serving wealthy families from 1890 until his death in 1935.

Thomas searched newspaper archives for any mention of Stuart and found something disturbing.

Dr.

Stewart had signed death certificates for seven other children between 1900 and 1920, all from wealthy families, all listed as accidental deaths or deaths due to natural causes complicated by mental deficiency.

Seven children, seven families, seven convenient explanations.

Thomas found one case that had been investigated more thoroughly.

The 1912 death of a 10-year-old boy named William Preston.

The child had died of pneumonia, but a suspicious neighbor had reported seeing extensive bruising on the boy weeks before his death.

An inquest had been held.

Dr.

Stewart had testified that the bruising was consistent with the boy’s mental deficiency and self-injurious behavior.

The wealthy Preston family had confirmed this account.

The death had been ruled natural despite the neighbors testimony.

But Thomas found something else.

A letter to the editor published in the Baltimore American in 1913 signed a physician’s conscience.

Sir, I write anonymously because I fear for my career, but I can no longer remain silent.

There’s a doctor in this city who has made himself available to certain wealthy families for a particular service, providing medical cover for child abuse.

When a child in these families shows signs of mistreatment, this doctor diagnoses mental deficiency and recommends isolation.

When bruises appear, he attributes them to self-injurious episodes.

When a child dies from abuse, he signs certificates listing accidents or natural causes.

He is paid handsomely for these services.

The families maintain their reputations.

The children suffer and die in silence.

And the law accepts a doctor’s word as truth, no matter how suspicious the circumstances.

How many children must die before we question the convenient diagnoses that allow wealthy families to abuse with impunity? The letter had appeared, but Thomas found no follow-up, no investigation of Dr.

Stewart, no consequences.

The medical establishment had closed ranks and the doctor had continued practicing for another 20 years.

Alice Whitmore had been one of his victims, diagnosed as mentally deficient to justify her isolation and abuse.

Her death conveniently certified as accidental.

Thomas traced what had happened to the Whitmore family after Alice’s death.

Edgar Whitmore had continued his business until his death in 1925.

Catherine had died in 1918 during the influenza epidemic.

The two sons had both survived to adulthood.

Robert had become a businessman.

Henry had become a lawyer and Thomas discovered had served on the board of the Maryland Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children from 1935 until his death in 1972.

Thomas found Henry Whitmore’s obituary.

It mentioned his child welfare work prominently.

Mr.

Whitmore devoted the latter part of his career to advocating for stronger child protection laws and was instrumental in establishing mandatory reporting requirements for suspected abuse.

There was a quote in the obituary that caught Thomas’s attention.

When asked why child welfare became his passion, Mr.

Whitmore would only say, “I failed to protect someone once.

I’ve spent my life trying to ensure others don’t make the same mistake.

” Thomas tracked down Henry’s surviving children.

His daughter, Elellanar Whitmore, now 78, lived in a retirement community in Talsson.

When Thomas called and explained his research, Ellanar’s response was immediate.

“You found the photograph.

” “I’ve been waiting for someone to find it,” she invited him to visit the next day.

Elellanar’s apartment was modest but filled with photographs including several of an elderly man Thomas recognized as Henry Whitmore.

My father never spoke about his sister until he was dying.

Ellaner said her voice steady but sad.

I was with him in the hospital in 1972.

He was 75 years old and he finally told me about Alice.

She poured tea with practiced movements.

He said Alice was the sweetest, gentlest child.

Quiet, thoughtful, always trying to please.

But their father hated her.

My father never understood why.

Maybe she reminded him of someone.

Maybe he resented having a daughter.

Maybe he was just cruel.

Whatever the reason, he singled her out for abuse from the time she was a toddler.

The photograph shows her excluded from the family portrait, Thomas said.

Ellaner nodded.

That was constant.

She was kept separate from the family, especially when there were visitors or social events.

If anyone asked about her, my grandfather would say she was ill or away visiting relatives.

He diagnosed her as mentally deficient, even though she was perfectly normal, just terrified and traumatized.

Your father was 12 when the portrait was taken.

Did he remember the session? He remembered everything about it.

He said Alice had to stand in the corner while they posed.

She wasn’t allowed to move or make noise.

The photographer, a Chinese man, my father said, kept looking at Alice, and my father realized the man was trying to help, trying to document what was happening.

Ellaner pulled out an old envelope.

After my father died, I found this among his papers.

He’d written it, but never sent it.

Thomas opened the envelope.

Inside was a letter dated 1968 addressed to the photographer of Thornon Studio.

Sir, I do not know if you are still living or if you will ever receive this letter, but I feel compelled to write it.

In October 1907, you photographed my family, the Whites of Baltimore.

You positioned a mirror to capture my sister Alice, who my father forced to stand apart from our family portrait.

You saw what was happening to her.

You tried to document it.

You filed a report with the child welfare authorities.

They came to our house, but my father was a skilled liar and our family doctor was complicit.

They never even spoke to Alice.

And 5 months later, my father beat her to death and called it an accident.

I was 12 years old.

I was too frightened to speak up, too powerless to protect her.

I have lived with that cowardice for 61 years.

But you tried.

You used your art to create evidence.

You attempted to save her when no one else would.

That attempt failed, but it mattered.

It proved that someone saw her.

Someone recognized her suffering.

Someone tried to help.

I became a lawyer in part because of you.

I have spent decades working to strengthen child protection laws, to make it harder for wealthy families to hide abuse, to ensure that a doctor’s complicit diagnosis isn’t enough to close an investigation.

If you are reading this, I want you to know you were not responsible for Alice’s death.

My father was the system that enabled him was the society that valued family reputation over children’s lives was you did what you could with the tools you had.

Thank you for seeing my sister.

Thank you for trying to make her visible.

Thank you for that photograph.

The only evidence that exists of her suffering and the only proof that someone cared.

Henry Whitmore.

Thomas’s eyes were wet.

He never sent it.

He didn’t know how to find the photographer.

He wrote it, I think, because he needed to say it, even if no one ever read it.

Ellaner paused.

But now you found the photograph.

Now someone knows.

That’s what my father wanted for Alice to be remembered, for her story to be told.

Thomas researched Frederick Chen more thoroughly.

After leaving Thornton Studio in 1915, Frederick had opened his own photography business, Chen photography, documentation, and portraiture.

The business had specialized in two types of work, standard commercial photography, and what Frederick called evidential photography, documenting scenes for legal and investigative purposes.

Thomas found newspaper articles about Frederick’s continued work with the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children.

Between 1907 and 1935, Frederick had testified in 37 child welfare cases.

His photographic evidence had led to the removal of children from abusive homes in 23 of those cases.

He’d refined his mirror technique over the years, developing ways to capture evidence that families couldn’t control or predict.

His methods had been adopted by other investigators and had influenced the development of forensic photography.

But Thomas found something that revealed the personal cost of Frederick’s work.

In a 1920 interview with a Baltimore newspaper, Frederick had been asked about his motivation.

A reporter asked, “Why do you devote so much time to this difficult work?” Frederick Chen responded, “Because I failed once.

” In 1907, I photographed a family and saw a child being abused.

I documented it as best I could.

I reported it, but it wasn’t enough.

The child died.

I think of her every time I work on a case.

I think, “This time, let my evidence be enough.

This time, let it save a life.

” I have succeeded many times since then, but I will never forget the ones I failed to save.

Frederick never married, had no children of his own.

He devoted his life to protecting other people’s children, driven by the memory of the ones he couldn’t save.

Thomas found Frederick’s obituary from 1940.

Frederick Chen, 58, respected photographer and child welfare advocate, died peacefully Tuesday.

He dedicated his life to using photography as a tool for justice, helping to establish standards for evidential photography still used today.

Those who worked with him remembered his quiet dedication and his insistence that every child deserves to be seen.

He requested that donations in his memory be made to the Maryland Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children.

Every child deserves to be seen.

Frederick had spent his life making invisible children visible, using mirrors and angles and light to capture what families tried to hide.

He’d seen Alice Whitmore isolated in the corner of his studio, excluded from her own family’s portrait, and he’d made sure that somewhere in some way, she would be documented, remembered, seen.

Thomas spent six months preparing the exhibition.

He titled it reflections of truth, photography, and hidden abuse in Victorian America.

The centerpiece was the Whitmore family portrait displayed large enough that visitors could clearly see both the posed family of four and the reflected image of Alice isolated and terrified in the corner.

Beside it, Thomas displayed Alice’s brief biographical information.

Alice Whitmore, 1899 to 1908.

Daughter, sister, victim Alice was systematically excluded from her family social life and photographic record.

She was diagnosed falsely as mentally deficient to justify her isolation and abuse.

She died at age 8 from injuries her father inflicted which were officially recorded as an accident.

This photograph is the only known image of Alice.

She appears not in the family portrait itself, but in the mirror’s reflection, visible only because photographer Frederick Chen positioned the mirror to document her presence and suffering.

Alice was invisible in life.

Frederick Chen made sure she would be seen in death.

The exhibition included Frederick’s reports to child welfare authorities, Sarah Morrison’s anguish notes, the investigation records that showed how the system had failed, and Henry Whitmore’s unscent letter.

It also displayed information about the 23 children Frederick’s photographic evidence had successfully rescued, showing that his techniques had saved lives even when they’d failed to save Alice.

The exhibition opened to significant media attention.

News coverage focused on the historical context.

How wealthy families in the Victorian era had been able to abuse children with impunity.

How complicit doctors had enabled the abuse.

How photography had emerged as a tool for documentation and justice.

Elellanar Whitmore attended the opening with her children and grandchildren.

They stood before the photograph.

Four generations acknowledging the child who’d been erased from family memory.

“She’s finally visible,” Elellanar said softly.

After more than a century of being hidden, dismissed, forgotten, she’s finally being seen.

“A young woman approached a social worker,” she explained, who worked with abused children.

“This exhibition should be required viewing for everyone in my field.

” She said, “It shows what happens when we accept convenient explanations instead of investigating thoroughly, when we value family reputation over children’s safety, when we let wealth and status protect abusers.

” She looked at the photograph again.

“That little girl in the corner, she’s every child we fail to see.

Every victim we don’t believe.

Every case we close too quickly because the family seems respectable.

Thank you for making her visible.

The exhibition ran for six months and was seen by over 15,000 visitors.

The photograph of the Whitmore family became iconic, reproduced in textbooks on child welfare history, used in training programs for social workers and investigators, featured in documentaries about the evolution of children’s rights.

Always.

The caption emphasized the same point.

Look closer.

See who’s been excluded.

Recognize who’s been made invisible.

Thomas gave numerous talks about the photograph and its significance.

At one presentation to child welfare professionals, he explained, “This photograph appears at first to be a standard Victorian family portrait.

A prosperous family well-dressed and well positioned.

Four people posing formally for the camera.

But look closer.

Look at the mirror.

In the mirror’s reflection, you can see what the family tried to hide.

A fifth person, a small child, isolated in the shadows, excluded from the family portrait, bearing visible signs of abuse, terrified and alone.

Frederick Chen positioned that mirror deliberately.

He was hired to photograph four people, and that’s what the main image shows.

But he made sure the mirror captured the truth, that there was a fifth member of this family, and she was suffering.

The photograph asks us to look beyond the surface, to question what we’re told, to seek out those who’ve been deliberately hidden or excluded.

It reminds us that official records can lie, that families can present false images, that children can suffer while everyone around them pretends not to see.

Alice Whitmore existed only in reflections.

In the mirror of this photograph, in the memories of a brother who spent his life trying to atone for not protecting her, in the conscience of a photographer who never forgot her, but she existed.

And now, finally, she’s visible.

The Maryland Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, established the Alice Whitmore Memorial Fund, providing resources for investigations of suspected abuse in affluent families, recognizing that wealth doesn’t prevent abuse, it just makes it easier to hide.

The Medical Board of Maryland issued a formal statement acknowledging Dr.

Harrison Stewart’s role in enabling child abuse through false diagnoses and complicit death certificates and established new protocols for investigating child deaths where abuse is suspected.

Most significantly, the exhibition prompted three people to come forward with their own stories of childhood abuse in prominent Baltimore families.

Abuse that had been hidden, dismissed, or explained away decades ago.

Their testimonies led to renewed investigations and in one case, criminal charges against an elderly abuser who evaded justice for 50 years.

Thomas stood in the empty exhibition hall on the final day, looking at the Whitmore family portrait one last time before it was carefully packed for the archives.

Four people in the photograph, five in the room, one child excluded and hidden, visible only in the mirror’s truthful reflection, but visible nonetheless, documented, remembered, finally seen.

Frederick Chen had understood something profound about photography and about truth.

That sometimes the most important things exist, not in what we choose to show, but in what we accidentally reveal.

That mirrors can capture what cameras miss.

That reflections can tell truths.

That posed images conceal.

He’d positioned that mirror to give Alice Whitmore something she’d never had in life.

Visibility, presence, proof of existence.

The family had tried to make her invisible.

Frederick had made sure she’d be seen, and more than a century later, thousands of people had looked at that mirror and seen her, had recognized her suffering, had understood what it meant to be excluded, hidden, erased.

The terrifying truth in the mirror wasn’t just about one abused child in 1907.

It was about every child who’s been made invisible, every victim who’s been conveniently ignored, every case that’s been closed because looking too closely might embarrass powerful families.

Look closer, the photograph says.

Question what you’re shown.

Seek out who’s been excluded.

Check the mirrors, the reflections, the shadows, because that’s where the truth often hides.

Alice Whitmore deserved to be in that family portrait.

She deserved to be acknowledged, protected, loved.

Instead, she was isolated, abused, and killed.

But she’s in the photograph now, in the mirror’s reflection, forever visible to anyone willing to look closely enough to see.

That is the mirror’s terrifying truth.

And its enduring message, see the invisible.

Believe what you see, and act before it’s too late.

Alice Whitmore’s reflection still watches from that mirror.

A silent witness to suffering and a powerful call to do better.

To look closer, see clearly, and protect those who’ve been hidden in the shadows.

She was invisible in life.

But in death, through the deliberate choice of one photographer who refused to look away, she became unforgettable.

News

In 1904, This Family Took a Picture. Decades Later, They Find Something Sinister In 1904, this family took a picture. Decades later, they find something sinister. In November 1978, Sarah Henderson entered her deceased grandmother’s study in the family’s Lincoln Park mansion. The Victorian home had belonged to the Henderson family for over 70 years, and Elellanena Henderson had been its meticulous keeper of memories and documents. The study contained decades of accumulated family history. Sarah worked methodically through each drawer of the mahogany desk, preserving what she could of her family’s past. When she opened the bottom drawer, her hands found a leather-bound photograph album hidden beneath financial papers. The album’s brass clasp had tarnished with age, and its leather binding showed the wear of many decades. Inside, sepia toned photographs documented Chicago’s high society from the early 1900s. Page after page revealed formal portraits, social gatherings, and family celebrations from a bygone era. One photograph stood out among the collection.

In 1904, This Family Took a Picture. Decades Later, They Find Something Sinister In 1904, this family took a picture….

🌊 MH370 Wreckage Finally Recovered After a Decade Lost—History’s Biggest Aviation Mystery Solved in Stunning Underwater Discovery That Will Shock the World 😱 In a heart‑pounding, dramatic narrator tone, the lead teases deep-sea sonar revealing twisted metal, personal effects preserved in silt, and decades of speculation finally colliding with reality, as experts and families confront answers they never thought they’d hear 👇

The Shadows of the Ocean In the early hours of March 8, 2014, the world was unaware that history was…

End of content

No more pages to load