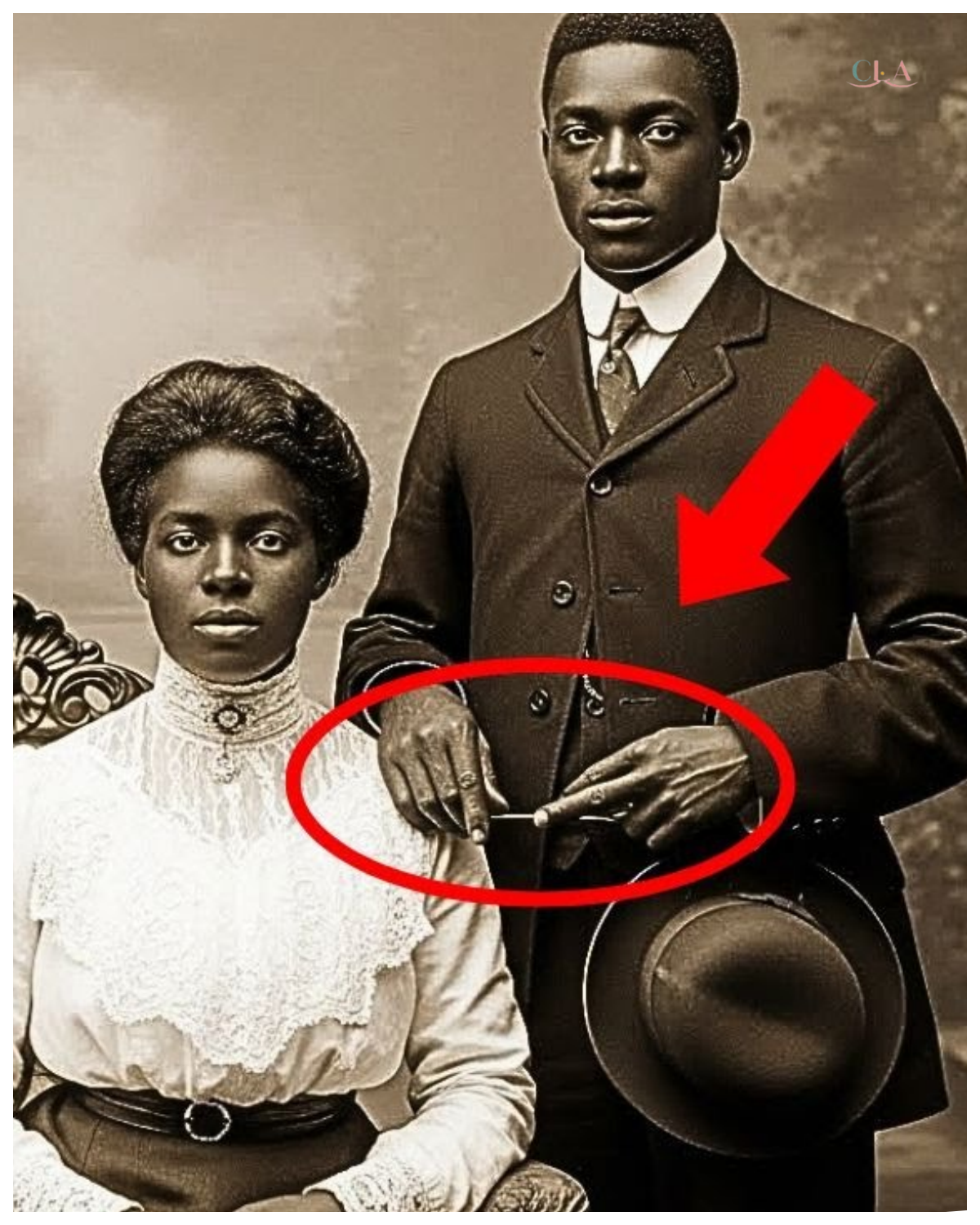

It was just engagement photo until you see where the groom’s hand is placed.

Dr.

Maya Richardson adjusted her reading glasses and leaned closer to her computer screen, studying the highresolution scan that had just arrived in her inbox.

The email subject line read simply, “Family heirloom, can you help date this?” But what appeared on her monitor was far more than a routine archival inquiry.

The photograph showed a young black couple posed in a formal studio setting.

The woman sat in an ornate chair, her posture perfect, wearing a high-necked white blouse with delicate lace trim and a dark skirt.

Her hair was styled in the Gibson girl fashion of the era, swept up with careful precision.

Her expression was serene but serious, her dark eyes looking directly at the camera with an intensity that seemed to pierce through more than a century of distance.

Behind her stood a young man in a crisp dark suit, his hand resting on her shoulder.

He was handsome, with a strong jawline and an equally serious expression.

The studio backdrop depicted a romantic garden scene complete with painted columns and flowering vines.

Maya had been a historian specializing in African-American life in the Jim Crow South for 15 years, working at the Atlanta History Center.

She had examined thousands of photographs from this period, documenting the lives and quiet resistance of black communities living under the brutal constraints of segregation.

But something about this photograph made her pause.

The studio stamp in the corner read Morrison Photography, Atlanta, Georgia, 1909.

The Morrison’s had been one of the few blackowned photography studios operating in Atlanta during that period, catering to the city’s African-American middle class.

Maya zoomed in on different sections of the image.

The woman’s clothing suggested education and relative prosperity.

The lace on her blouse was expensive.

Her shoes were leather and well-maintained.

The man’s suit was tailored perfectly.

These were people of some standing in their community.

But it was the position of the man’s hand that made Mia’s breath catch.

His hand rested on the woman’s shoulder, but not in the relaxed protective gesture typical of engagement photographs.

His fingers were arranged in a specific configuration, thumb extended outward, index and middle fingers pressed together and pointed downward, ring finger and pinky curled inward.

The position looked casual at first glance, but the more Maya studied it, the more deliberate it appeared.

She had seen something similar before, though she couldn’t immediately place where.

Maya spent the next two hours comparing images, looking at dozens of engagement photographs from Black Atlanta between 1900 and 1920.

In every other image, the hand positions were conventional.

None showed this particular finger configuration.

She picked up her phone and composed a careful reply to the sender, a woman named Jennifer Matthews, who had identified herself as a descendant of the couple.

Thank you for sharing this remarkable image.

The photograph is definitely from 1909.

I’d love to learn more about your ancestors.

Do you know their names? The response came within minutes.

The woman is my great great grandmother, Clara Bennett.

The man is Thomas Wright, who became her husband.

I don’t know much more than that.

Why? Is there something unusual about it? Clara Bennett.

The name triggered something in Maya’s memory.

She opened her filing cabinet and began pulling out folders, searching through her collection of primary sources.

20 minutes later, she found it.

A brief mention in a 1909 issue of the Atlanta Independent.

Miss Clara Bennett, teacher at the Auburn Avenue School, was called upon to give testimony regarding the tragic events of March 15th.

March 15th, 1909, 6 months before this photograph would have been taken.

Maya’s hands trembled as she searched the newspaper archives for more information.

What she found made her heart pound.

The front page of the March’s 16th edition carried the headline, “Community and mourning, Robert Johnson lynched.

” The article described how a young black man had been accused of speaking disrespectfully to a white woman.

A mob had dragged him from his workplace, beaten him, and hanged him from a tree near the railroad tracks.

But buried in the fourth paragraph was a sentence that changed everything.

Miss Clara Bennett, a witness to the initial confrontation, has stated that young Mr.

Johnson’s words were misconstrued and that he meant no disrespect.

Clara Bennett had witnessed the incident that led to a lynching, and she had been willing to publicly state that the accusations were false.

Maya immediately called Jennifer Matthews.

The phone rang three times before a woman’s voice answered.

Ms.

Matthews, this is Dr.

Richardson from the Atlanta History Center.

I need to ask you something important.

Did your family ever mention that Clara Bennett was in danger? That she was threatened? There was a long pause on the other end of the line.

My grandmother used to say that Clara was the bravest woman who ever lived.

She said Clara saw something terrible and refused to stay quiet even when people told her she should.

Grandmother said Clara had protectors, men who watched over her day and night, but she never explained what it all meant.

Maya felt her pulse quicken.

Did she ever mention Thomas, Wright? What he did for a living? She said he was a soldier, that he came back from the army and worked as a railroad porter.

But there was something else about him, something grandmother would start to say, and then stop herself like it was a secret she wasn’t supposed to tell.

After the call ended, Mia dove deeper into the archives.

She found Clara’s employment records at the Auburn Avenue School.

Clara had been 23 years old in 1909, teaching reading and arithmetic to black children in a two- room schoolhouse.

Her evaluations described her as dedicated, intelligent, and principled.

Then Maya found the incident report from March 15th.

Robert Johnson, age 19, had been working as a delivery driver.

He had made a delivery to a store where a white woman was shopping.

According to multiple black witnesses, Johnson had simply said, “Excuse me, ma’am.

” went passing her in the narrow aisle.

The woman’s husband, who arrived moments later, claimed Johnson had been insolent and threatening.

Clara Bennett had been in the store purchasing supplies for her classroom.

She had seen and heard everything.

And unlike the other witnesses, who understood the mortal danger of contradicting a white person’s story, Clara had gone to the police and then to the newspaper to state what actually happened.

It hadn’t saved Robert Johnson.

Nothing could have saved him once the accusation was made.

But Clara’s testimony had been published, creating a record that challenged the official narrative.

Maya found more newspaper articles from the following weeks.

Anonymous letters to the editor praising Clara’s courage.

A brief notice that Clara had received threatening messages.

A tur statement from the school board supporting her continued employment despite recent controversies.

Then in an article dated April 3rd, she found something that made her sit up straight.

Members of the community have expressed concern for Miss Bennett’s safety.

Unnamed sources report that protective measures have been implemented.

Protective measures.

Unnamed sources.

Maya looked again at the photograph, at Thomas Wright’s hand with its strange finger configuration, at the serious expressions on both faces, at the deliberate formality of the pose.

This wasn’t just an engagement photograph.

This was a message, a declaration, a warning to anyone who might be watching.

Maya needed to know more about Thomas Wright.

She started with military records, searching through databases of African-American soldiers who had served in the early 1900s.

The US Army had been segregated with black soldiers serving in separate units, often facing discrimination even as they wore the uniform.

She found him in the records of the 25th Infantry Regiment, one of the army’s all black units.

Thomas Wright had enlisted in 1903 at age 18 and served for 5 years stationed at Fort Wuka in Arizona territory.

His service record noted him as reliable, disciplined, skilled marksman.

He had received an honorable discharge in 1908 and returned to Atlanta, his hometown.

But what had he done after returning? Railroad Porter, Jennifer had said.

Maya searched employment records and city directories.

She found Thomas listed at an address on Auburn Avenue, the heart of Black Atlanta, working for the Southern Railway Company.

Then she found something unexpected.

In the membership records of the Wheat Street Baptist Church, one of Atlanta’s prominent black churches, Thomas Wright was listed not just as a member, but as part of something called the Brotherhood Committee.

The term was vague, giving no indication of what the committee actually did.

Maya called Dr.

James Peterson, a colleague who specialized in black churches and their role in community organizing during the Jim Crow era.

James, have you ever heard of something called a brotherhood committee in early 1900’s black churches? Brotherhood committees were common, James replied.

Usually they organized charity work, helped families in need, that sort of thing.

Why? What if they did something else? Something they couldn’t talk about openly.

There was a pause.

You’re talking about protection groups, self-defense organizations.

They existed, Maya, but they were extremely secretive.

If white authorities had known about organized groups of black men preparing to defend their community, it would have been seen as insurrection.

The consequences would have been catastrophic.

How would they have operated? in complete silence.

They would have used codes, signals met in secret.

Members would have been carefully vetted.

They would have been ready to protect specific individuals under threat, to gather intelligence about potential violence, to create networks of safe houses.

They were essentially underground resistance cells operating inside churches and fraternal organizations.

Maya felt the pieces beginning to align.

Thomas Wright, a trained soldier, returns to Atlanta and joins a brotherhood committee.

Clara Bennett witnesses a lynching and publicly contradicts the justification for it.

Clara receives threats.

And then months later, Thomas and Clara pose for an engagement photograph where his hand is positioned in a way that looks nothing like any other photograph from that era.

She needed to find out what that hand position meant.

Maya reached out to Dr.

Leonard Washington, a historian who had written extensively about coded communication among enslaved people and their descendants.

She emailed him the photograph highlighting Thomas’s hand position.

His response came the next morning.

This is extraordinary.

That hand configuration matches descriptions I’ve found in oral histories of signals used by protection groups in the early 1900s.

The extended thumb, the pointed fingers, the curled pinky.

It’s a deliberate sign.

I’ve seen references to it meaning under protection or guarded.

It was a way of communicating that someone was not alone, that harming them would bring consequences.

Where did you find this? Mia’s heart raced as she typed her response, explaining everything she had discovered about Clara and Thomas.

Leonard called her within the hour.

Maya, what you found is remarkable.

These protection networks have been largely lost to history because they had to be so secret.

If you can prove that this photograph was a deliberate message, that Thomas was signaling Clara’s protected status, you’ll be documenting something incredibly important.

But why make it visible in a photograph? Wasn’t that risky? Think about it strategically.

A photograph is a record.

It’s evidence.

If something happened to Clara, that photograph would prove she wasn’t just some random target.

It would show she had organized protection.

That might not have prevented violence, but it would have changed its meaning.

It would have turned an attack on her into an attack on the organization protecting her.

It raises the stakes.

Maya understood.

The photograph was both shield and sword.

Maya spent the next week immersed in archives, piecing together the world Clara and Thomas had inhabited.

She found city directories, church records, newspaper articles, and census data.

Building a map of black Atlanta in 1909.

Auburn Avenue was the center of it all.

Known as Sweet Auburn, it would later be called the richest Negro Street in the world by Web Dubo.

In 1909, it was already thriving with blackowned businesses, churches, and social organizations.

Clara’s school was there.

Thomas’ Church was there.

The Morrison Photography Studio was there.

Maya found that Thomas wasn’t the only veteran in the congregation at Wheat Street Baptist.

At least eight other men in the church had served in the army’s black regiments.

She found their names in the membership records, cross-referenced with military service records.

All had returned to Atlanta between 1906 and 1909.

All were listed as members of the Brotherhood Committee.

She created a timeline.

Robert Johnson was lynched on March 15th, 1909.

Clara’s testimony was published on March 16th.

By March 20th, the newspaper reported that Clara had received threatening letters.

On April 3rd, protective measures were mentioned.

The engagement photograph was dated September 1909, 6 months after the lynching.

Maya found Thomas and Clara’s marriage license.

They had married on October 2nd, 1909 at Wheat Street Baptist Church.

The witnesses listed included four men, all members of the Brotherhood Committee, all veterans.

Then she found something that made everything crystallize.

In the November 1909 edition of the Atlanta Independent, a small article reported, “The trial of five men accused in the death of Robert Johnson concluded this week.

Miss Clara Bennett provided crucial testimony.

The defendants were found guilty of manslaughter and sentenced to prison terms.

Clara had testified and she had lived to see justice, however incomplete, however rare, in that time and place.

” Maya pulled the trial transcripts from the county courthouse archives.

Clara’s testimony was recorded in careful legal language.

She described exactly what she had seen and heard.

She identified the men who had dragged Robert Johnson away.

She stated clearly that Johnson had done nothing wrong, that he had been polite and respectful, that the accusations against him were false.

The defense attorney had questioned her harshly, trying to undermine her credibility.

Miss Bennett, are you aware that your testimony contradicts that of respected members of this community? Are you certain you remember correctly? Might you have been mistaken? Clara’s response, preserved in the transcript, was steady.

I am certain of what I saw and heard.

I have no doubt whatsoever.

Robert Johnson was murdered for something he did not do.

That is the truth.

Maya found herself blinking back tears as she read the words.

The courage it must have taken to sit in that courtroom facing hostile questioning, knowing that her testimony was painting a target on her back and still refusing to back down.

But Clara hadn’t been alone.

Maya cross referenced the dates.

During the trial, which lasted 3 weeks in October 1909, Thomas Wright had taken a leave of absence from his railroad job.

So had two other members of the Brotherhood Committee.

They had been there in that courtroom every single day.

Maya found a photograph from the trial published in the newspaper.

It showed the courtroom crowd and there standing along the back wall were several black men in dark suits.

Their faces were serious, their postures alert.

Maya recognized Thomas Wright immediately.

Next to him stood the other veterans from Wheat Street Baptist.

They had been Clara’s shield, her protectors, her proof that she was not alone.

The photograph that Clara and Thomas had taken in September, just before the trial began, had been their declaration.

The hand position was their code.

The formal pose was their statement, “We are ready.

We are organized.

We are protecting her.

” And anyone who understood the signal would have known exactly what it meant.

Maya contacted Jennifer Matthews again, asking if there were any other family documents, letters, or photographs.

Jennifer invited her to visit, saying she had found more items in her grandmother’s belongings.

Jennifer’s home was in the historic old fourth ward neighborhood not far from where Clara and Thomas had lived.

She welcomed Maya into a living room filled with family photographs spanning generations.

“I found these after we last spoke,” Jennifer said, pulling out a worn leather album.

“I’d looked through it before, but I wasn’t paying attention to the details.

” “Mia opened the album carefully.

” The first pages showed Clara and Thomas’s wedding photograph, formal, dignified, surrounded by family and friends.

Then more photographs.

Clara standing in front of her schoolhouse with students Thomas in his railroad uniform.

Family gatherings at Wheat Street Baptist Church.

Then Maya saw it.

A photograph dated 1912, 3 years after the engagement photo.

It showed a group of men standing in front of the church.

All wore dark suits.

And several of them had their hands positioned in ways that echoed Thomas’s gesture from the engagement photograph.

Deliberate finger configurations that looked casual but weren’t.

“These are the Brotherhood Committee members,” Maya said quietly.

Jennifer leaned closer.

How can you tell the hand positions? Look at how they’re standing.

Three of them have their hands positioned exactly like Thomas’s in the engagement photo.

It’s a signal, a code.

Maya photographed each image, her mind racing.

This wasn’t just one photograph with a hidden message.

This was documentation of an entire network preserved in plain sight for anyone who knew how to read it.

Then Jennifer pulled out a small wooden box.

This was Clara’s.

I’ve never been able to open it.

The box was locked.

Its brass hardware tarnished with age.

Maya examined it carefully.

Do you mind if I try to open it? I know a conservator who specializes in antique locks.

Two days later, after careful work by the conservator, the box opened.

Inside were letters carefully preserved in oil cloth to protect them from moisture and decay.

Maya’s hands trembled as she unfolded the first letter dated April 1909.

It was addressed to Clara, written in a careful, educated hand.

Dear Miss Bennett, we write to express our deepest admiration for your courage and speaking truth.

We know you have been threatened.

We want you to know that you are not alone.

Brothers are watching.

You are protected.

If you need anything, send word through the church.

You will always have a place to go.

Always have people ready to stand with you.

Your bravery honors Robert’s memory and strengthens all of us in solidarity.

The letter was unsigned, but the handwriting matched samples Maya had found in church records.

It was from Thomas Wright.

More letters followed, spanning several months.

Some were practical, detailing arrangements for Clara to be accompanied to and from school.

Others were encouraging, reminding her that her testimony mattered, that truth mattered, that she was doing something important and dangerous and necessary.

One letter dated September 1909, just before the engagement photograph was taken, was more personal.

Clara, when we take our photograph tomorrow, I want the whole world to see what I see.

A woman of extraordinary courage who refused to let injustice pass without witness.

My hand on your shoulder is not just because I love you, though I do with all my heart.

It is a signal to anyone watching that you are under my protection.

Under our protection.

Let them see it.

Let them understand.

You’re not alone.

You will never be alone.

Thomas.

Maya read the letter three times.

Tears streaming down her face.

This was the proof, the confirmation.

The photograph had been exactly what she suspected.

A deliberate message, a coded signal, a public declaration of protection.

Jennifer was crying, too.

I never knew.

My grandmother never told me how brave she was.

Your great great grandmother changed history.

Maya said her testimony helped convict the men responsible for lynching.

That almost never happened and she survived because of Thomas and the network he organized.

This is an incredible story.

But Maya knew there was more to find.

How had Clara lived after the trial? What had happened to Thomas and the Brotherhood Committee? Had their protection work continued? She needed to trace the rest of their lives.

Maya returned to the archives with renewed purpose, tracking Clara and Thomas through census records, city directories, and newspaper mentions.

The 1910 census, taken just months after their marriage, showed them living on Auburn Avenue.

Thomas was still working for the railroad.

Clara was listed as a teacher.

Living with them was a young man named David Johnson, Robert Johnson’s younger brother.

Maya felt her breath catch.

They had taken in the brother of the man whose death had started everything.

They had given him a home, a family, protection.

She found David’s school records.

He had been 16 in 1910, enrolled at Atlanta Baptist College, which would later become Morehouse College.

Someone had paid his tuition.

Maya found the payment records.

The money had come from the Wheat Street Baptist Brotherhood Committee.

The network had extended beyond protection.

They were building futures, creating opportunities, investing in the next generation.

Maya found more.

In 1911, Clare had been promoted to principal of the Auburn Avenue School.

An article in the Atlanta Independent praised her leadership.

Mrs.

right has transformed the school into a beacon of excellence, providing our children with education that prepares them not just to survive, but to thrive.

Thomas had advanced, too.

By 1913, he was a senior porter supervisor for Southern Railway, responsible for training new employees.

His position gave him legitimate reasons to travel throughout the South, and Ma suspected it also gave him opportunities to gather information and connect with other protection networks in other cities.

The Brotherhood Committee at Wheat Street Baptist continued to operate.

Maya found mentions of their charitable work, providing food to families in need, helping with medical expenses, organizing legal defense funds, all respectable public activities that masked their other, more dangerous work.

She found a 1914 photograph from a church anniversary celebration.

Thomas and Clara stood among a large group of congregants.

But Maya noticed something.

The veterans who made up the Brotherhood Committee were positioned strategically throughout the group.

Their placement too deliberate to be accidental.

They were still protecting, still watching, even in a church photograph.

Then Maya found evidence of how far their network extended.

In a 1915 article about a court case in Birmingham, Alabama, a black woman who had witnessed police brutality was preparing to testify.

The article mentioned that community supporters from Atlanta were assisting with her safety during the trial.

Maya cross referenced the dates.

Thomas Wright had taken leave from his railroad job during that exact period.

Two other Brotherhood Committee members had traveled to Birmingham at the same time.

They were exporting their model, sharing their knowledge, building networks across cities.

The work was dangerous and exhausting, but it was also effective.

Maya found records of several trials between 1910 and 1917 where black witnesses testified against white defendants in cases of violence and injustice.

Most of these witnesses came from Atlanta or had connections to Wheat Street Baptist Church.

And in many cases, the witnesses were accompanied by community supporters, unnamed men who stood watch, who made it clear that the witnesses were protected.

Clara and Thomas had started something that grew beyond them.

Their courage and organization had created a template for resistance and protection that others could follow.

But Maya wondered what price they had paid.

Living under constant threat, always vigilant, always aware that one mistake could bring violence down on themselves or others.

What toll had that taken? She found a clue in a 1916 letter from Clara to her sister, preserved in Jennifer’s family collection.

There are days when I am tired.

When the weight of what we carry feels too heavy.

Thomas has nightmares.

He dreams of things he saw in the army.

Things he has seen since.

But then I think of Robert.

Of his family.

Of all the people we have helped stay safe.

And I know we must continue.

This work matters.

Someone must stand up.

Someone must refuse to look away.

If not us, then who? Maya felt the humanity in those words.

Clara and Thomas weren’t heroes from a myth.

They were real people who got tired, who were afraid, who doubted sometimes, but they kept going anyway.

That Maya thought was what real courage looked like.

Mia began preparing her findings for publication, knowing that Clara and Thomas’ story needed to be shared.

But first, she wanted to understand what had happened to the photograph itself, how it had survived, why it had been preserved.

She called Jennifer again.

The engagement photograph.

Do you know where it was kept all these years? Who had it? Jennifer thought for a moment.

My grandmother kept it in a frame on her bedroom dresser.

She looked at it every day.

When I was little, I asked her about it and she said it was the most important photograph our family owned.

She said it represented love and protection and courage and that I should never forget it.

Did she know what the hand position meant? I don’t think she knew the specific code, but she knew it meant something special.

She told me that Thomas was Clara’s protector, that he kept her safe when people wanted to hurt her.

Maya made a request.

Would you be willing to let the Atlanta History Center display the photograph with the full story? I think people need to see this.

They need to understand what Clara and Thomas did.

Jennifer didn’t hesitate.

Yes, Clara would want people to know she didn’t stay silent in life.

Her photograph shouldn’t stay hidden now.

Ma worked for weeks on the exhibition text, crafting the story to honor Clara and Thomas while making their actions understandable to a modern audience.

She included the newspaper articles about the lynching, Clara’s testimony, the trial records, and the letters from Thomas.

She consulted with Dr.

Leonard Washington to explain the hand signal and its significance.

The exhibition opened in February 2024 titled Courage and Code, Clara Bennett and the Secret Networks of Protection.

The engagement photograph was the centerpiece dramatically lit and enlarged so visitors could see every detail.

Maya gave a talk at the opening standing before a packed auditorium.

What you’re about to see is not just a love story, though it is that.

It’s not just a story of resistance, though it is that, too.

It’s a story about ordinary people who made the extraordinary choice to stand against injustice, knowing the cost, and who built systems of protection and solidarity that saved lives.

She clicked to an image of the photograph.

Look at Thomas Wright’s hand.

See how his fingers are positioned? That’s not an accident.

That’s a code, a signal that meant under protection.

This photograph was taken 6 months after Clara Bennett witnessed a lynching and became the only person willing to publicly state that the victim was innocent.

She received death threats.

She was in danger every day.

The audience was silent, riveted.

Thomas Wright was a veteran who organized a secret network of men to protect community members under threat.

This photograph was their declaration.

It was saying, “We see you watching her.

We are watching you.

If you harm her, you will face consequences.

” And it worked.

Clara testified at trial.

The murderers were convicted, which was almost unheard of in 1909.

And Clara lived a long, full life, continuing to teach and lead and inspire.

Maya paused, looking at the faces in the audience.

This photograph has been hidden in a family album for over a century, but Clara and Thomas left it for us to find.

They documented their resistance.

They created evidence.

They made sure their story could be told.

Today, we’re honoring that by telling it.

The exhibition drew enormous crowds.

Local media covered the story.

National news outlets picked it up.

The photograph went viral on social media with millions of people sharing it and discussing its significance.

Scholars from across the country contacted Maya sharing similar findings from their own research.

Photographs with unusual hand positions, letters mentioning brotherhood committees, evidence of other protection networks in other cities.

Clara and Thomas’ story was opening doors to a hidden history that had been waiting to be discovered.

Jennifer attended the exhibition opening, bringing her children and grandchildren.

They stood before the photograph together, four generations, looking at Clara and Thomas’s faces.

Your great great great great great grandmother was a hero.

Jennifer told her youngest grandchild, a girl of seven, and she saw something wrong and she spoke up even when it was dangerous.

And your great great great great-grandfather made sure she was safe.

They loved each other and they loved justice.

The girl studied the photograph seriously.

They looked strong.

They were, Jennifer said.

They were.

As Maya’s research continued, she began tracing what had happened to the Brotherhood Committee and its members in the years after Clara’s testimony.

The work led her deeper into Atlanta’s black history and into the national story of resistance and self-defense during Jim Crow.

Thomas Wright remained active with the Brotherhood Committee until 1917 when America entered World War I.

Despite his age, he was 32.

Thomas tried to reinlist in the army.

His application was rejected due to his previous service and age, but Maya found something remarkable in his subsequent activities.

In 1918, Thomas became a coordinator for the Atlanta chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, which had been founded in 1909, the same year as Clara’s testimony.

The timing was significant.

The Hoto ACP’s early work focused heavily on investigating and publicizing lynchings, providing legal defense for black people facing injustice, and organizing community protection efforts.

Maya found Thomas’ name on documents related to several major cases.

He was listed as a community liaison and witness coordinator.

roles that likely meant he was doing exactly what he had done for Clara, organizing protection for people brave enough to testify against racial violence.

Clara’s path was equally impressive.

By 1920, she was supervising six schools in Atlanta’s black neighborhoods, training new teachers, and developing curriculum.

But Maya found evidence that Clara’s work extended beyond education.

She was a founding member of the Atlanta Women’s Political Club, which registered black women to vote after the 19th Amendment passed in 1920.

Despite the enormous barriers and dangers that black women faced in exercising that right in the South, a 1922 photograph showed Clara standing with a group of women outside a polling place.

The same deliberate positioning was evident.

Women arranged strategically, some with hand positions that echoed the old brotherhood committee signals.

The protection networks had evolved, expanded, included women in leadership roles.

Maya found that several members of the original Brotherhood Committee went on to prominent roles in civil rights organizations.

One became a lawyer who handled dozens of civil rights cases.

Another founded a blackowned insurance company that provided economic security to families who might otherwise have been vulnerable to economic retaliation for civil rights activities.

David Johnson, Robert’s younger brother, whom Clara and Thomas had taken in, graduated from Atlanta Baptist College in 1914 and became a teacher.

By 1925, he was principal of a school in Birmingham, Alabama.

His obituary in 1968 mentioned that he had been active in community protection and civil rights work for over 50 years.

The ripples extended far beyond Atlanta.

Maya found connections between wheat street Baptist Church’s brotherhood committee and similar groups in other cities.

The model of organized secret protection networks for witnesses and activists appeared in Memphis, Birmingham, Nashville, and New Orleans.

While she couldn’t definitively prove that Thomas and his colleagues had spread the model, the timing and similarities were too striking to be coincidental.

She found a 1930 letter from Thomas to a pastor in Memphis discussing the arrangements we discussed for your witness protection efforts and offering to share our organizational methods and communication systems.

The work had become a movement.

Clara and Thomas themselves remained active into their later years.

The 1940 census showed them still living on Auburn Avenue, their home now a hub for community organizing.

Thomas was listed as retired from the railroad but working as a consultant for the NAACP.

Clara was retired from teaching but listed as a community educator.

Maya found a 1945 photograph of Clara, now 69 years old, standing with a group of young people preparing to register to vote.

Clara’s expression was the same as in the engagement photograph, serious, determined, fearless.

One of the young women in the photograph had her hand positioned in the old signal.

The codes were being passed down, kept alive, adapted for new generations.

Thomas died in 1948 at age 63.

His obituary in the Atlanta Daily World, the city’s black newspaper, ran half a page and described him as a tireless advocate for justice and protector of the community.

Clara lived until 1962, dying at age 76, having witnessed the early years of the civil rights movement and the rise of leaders like Dr.

Martin Luther King Jr.

who had been born in Atlanta and whose own work was built on the foundation that people like Clara and Thomas had laid.

Clare’s obituary described her as an educator, activist, and witness to history who never backed down from speaking truth.

It mentioned her testimony in 1909, but didn’t explain the full story of what that testimony had cost and what Thomas and the Brotherhood Committee had done to keep her alive.

Those details had remained hidden, protected by the same secrecy that had kept the network safe during its most dangerous years until now.

Maya sat in her office, surrounded by documents and photographs, and marveled at the scope of what Clara and Thomas had built.

It wasn’t just about one testimony, one trial, one photograph.

It was about creating systems that allowed truth to be spoken, that made resistance possible, that protected the vulnerable and honored the courageous.

Their legacy was encoded in photographs, preserved in church records, hidden in plain sight for over a century.

And now, finally, it could be fully told.

The public reaction to Clara and Thomas’ story exceeded anything Maya had anticipated.

Within days of the exhibition opening, the engagement photograph became one of the most shared historical images on social media.

News outlets across the country covered the story, and several major documentaries reached out to Maya about featuring the research.

But the most meaningful responses came from families who realized they had their own connections to the story.

An elderly man named Marcus appeared at the Atlanta History Center 3 weeks after the exhibition opened, carrying a worn photograph album.

He introduced himself to Maya with trembling hands.

My grandfather, he said, opening the album to a photograph of a man in a dark suit.

Was one of them, one of the brotherhood committee.

I found his name in the church records you published.

I never knew what it meant.

I just knew he was somebody important, somebody people respected.

The photograph showed a man standing with his hand positioned in the same signal Thomas had used.

Marcus’ eyes filled with tears as he recognized it.

He was part of this, part of protecting people.

He was, Ma confirmed.

Your grandfather was a hero.

More families came forward, descendants of other Brotherhood Committee members, grandchildren of people Clara had taught, great-grandchildren of witnesses who had been protected during other trials.

Each brought photographs, letters, stories that added pieces to the larger picture.

One woman brought a diary that her grandmother had kept, describing the fear of testifying against a white man who had attacked her brother and the relief of knowing Thomas Wright’s people were watching over me.

Another man brought a photograph of his great-grandfather standing with Thomas Wright outside Wheat Street Baptist Church, both with their hands positioned in the signal.

The Atlanta History Center expanded the exhibition to include these new materials.

What had started as one photograph became a comprehensive documentation of an entire movement of resistance and protection.

Academic recognition followed.

Maya received invitations to present her research at conferences across the country.

Universities incorporated Clara and Thomas’ story into their curricula.

The photograph appeared in textbooks and documentaries, in museum exhibitions about African-American history and resistance during Jim Crow.

But the recognition that meant the most came from civil rights veterans who had lived through the later struggles of the movement.

A woman who had been a freedom writer in 1961 came to see the exhibition and stood for a long time before the engagement photograph.

“We had people like this, too,” she told Maya.

“When we rode the buses, when we sat at lunch counters, there were always people watching, people ready to step in if things got violent.

We knew they were there.

It made us brave enough to do what we had to do.

I never knew it went back this far.

I never knew the history of it.

It goes back much further than 1909.

Maya explained.

Clara and Thomas were continuing traditions of resistance and protection that probably go back to slavery to the Underground Railroad to every time people organized to keep each other safe.

They just documented it better than most.

The city of Atlanta designated the site of Clara and Thomas’ home on Auburn Avenue as a historic landmark.

A marker was installed with their photograph and a description of their work.

The Auburn Avenue School, where Clara had taught, was renamed the Clara Bennett School in her honor.

Jennifer was invited to speak at the dedication ceremony.

She stood before a crowd of hundreds, her voice strong and clear.

My great great grandmother lived in a time when speaking truth could get you killed.

She spoke it anyway.

My great great-grandfather organized men to protect her and others who had the courage to stand up against injustice.

They did this work in secret, never seeking recognition, never asking for thanks.

They did it because it was right, because someone had to.

Because silence in the face of evil is itself a form of evil.

She paused, looking at the crowd.

That engagement photograph that’s become so famous.

It wasn’t just about their love, though they loved each other deeply.

It was a statement, a promise, a warning.

It said, “We are here.

We see you.

We will not be silent.

We will not let you terrorize us without consequence.

” And more than a century later, that message still matters.

The crowd applauded, but Maya noticed something else.

Throughout the audience, particularly among the older attendees, people were quietly showing each other hand positions, comparing photographs on their phones, making connections.

The code was being remembered, reclaimed, celebrated.

After the ceremony, Maya stood with Jennifer and Marcus and the other descendants who had come forward.

They formed a group linked by their ancestors courage and their shared commitment to making sure these stories were never forgotten again.

There are more stories like this, one of the descendants said.

More photographs with hidden meanings, more networks we don’t know about yet.

Then we’ll find them, Maya replied.

We’ll keep looking.

We’ll keep telling these stories.

That’s how we honor what they did.

By making sure their resistance is remembered, studied, celebrated.

As the sun set over Auburn Avenue, Maya thought about Clara and Thomas, about the life they had built together, about the risks they had taken and the legacy they had left.

Their engagement photograph had traveled through more than a century, carrying its secret message, waiting for the right moment to reveal its truth.

That moment had finally come.

6 months after the exhibition opened, Mia stood in the Atlanta History Center, giving her final tour before the display would be redesigned and permanently installed in the museum’s main gallery.

She had given this tour dozens of times, but it never lost its power.

“When you look at this photograph,” she told the group gathered around her, “you’re looking at an act of resistance.

” Clara Bennett and Thomas Wright knew that someone someday would examine this image closely enough to understand what they were saying.

They left us a message across time.

A young woman in the group raised her hand.

What do you think they would want us to do with their story now that we know it? Maya had been asked this question before, but she always paused before answering, wanting to get it right.

I think they would want us to recognize that resistance has always existed.

That even in the darkest times, people find ways to fight back, to protect each other, to refuse to accept injustice.

They would want us to know that we’re not the first generation to face these challenges, and we won’t be the last.

But we can learn from their courage and their strategies.

She gestured to the photograph.

They would want us to look closely at the world around us, to see the hidden messages, to understand that there are always people working quietly to make things better.

and they would want us to ask ourselves, “Well, what are we willing to risk for justice? Who are we protecting? Who is protecting us?” The tour continued, but Maya noticed the young woman stayed behind, studying the photograph intently.

When the others had moved on, she approached Maya.

My grandmother was part of the civil rights movement in the 1960s.

She was beaten during a sitin.

She never talked much about it, but she always said she knew people were watching out for her, that she was never truly alone.

Do you think? I think these networks never really stopped, Maya said gently.

They evolved, adapted, changed names and methods, but the principle remained the same.

Organized protection for people brave enough to stand up.

Your grandmother was probably connected to descendants of groups like the Brotherhood Committee.

The tradition continued.

The young woman pulled out her phone and showed my a photograph.

This is my grandmother at the sight in right before they were arrested.

There are men standing in the background.

I never paid attention to them before, but look at their hands.

Maya looked.

The hand positions were subtle but unmistakable.

The old signals still being used 50 years after Clara and Thomas’s engagement photograph still meaning the same thing.

We are watching.

You are protected.

Document everything you have.

Maya told her.

Every photograph, every story.

This is history that matters.

Later that evening, Maya returned to her office and pulled up the engagement photograph on her computer one more time.

She had looked at it thousands of times by now, but she never tired of it.

The dignity in Clara’s face, the strength in Thomas’s posture, the deliberate, careful positioning of his hand on her shoulder.

They had been so young.

Clara was 23, Thomas was 24.

They had their whole lives ahead of them, and they chose to spend those lives in dangerous, difficult, essential work.

They could have stayed silent.

They could have looked away.

No one would have blamed them.

But they hadn’t.

And because of their courage, Clara had lived to testify.

Justice, however incomplete, had been served.

Robert Johnson’s death had been acknowledged as murder, not justified punishment.

And a network of protection had been built that would continue for generations.

Maya opened a new document on her computer and began typing.

There was more work to do, more photographs to analyze, more codes to decipher, more hidden histories to bring into the light.

Because Clara and Thomas’ story wasn’t unique.

It was one example of countless acts of resistance and courage that had been happening all along, documented in photographs and letters and church records, waiting for someone to look closely enough to see them.

Maya thought about the hand signal, about how it had been preserved across generations, adapted and used by people fighting for justice in every era.

It was a simple gesture, thumb extended, fingers pointed, pinky curled, but it carried profound meaning.

protection, solidarity, resistance, love.

She thought about how many photographs might be sitting in atticss and albums right now hiding similar messages.

How many families possessed pieces of this hidden history without realizing their significance? And she thought about Clara and Thomas themselves, two young people in love who had posed for an engagement photograph in 1909, knowing they were creating something more than a personal momento.

They were creating evidence, documentation, a message that would outlast them.

The message was simple but powerful.

We were here.

We resisted.

We protected each other.

We refused to be silent.

We built something that mattered.

More than a century later, that message had finally been heard.

And it was changing how people understood history, resistance, and the power of ordinary people to fight extraordinary injustice.

Maya saved her document and closed her computer.

Tomorrow she would start investigating another photograph that had been sent to her.

Another possible code, another hidden story.

But tonight, she would simply be grateful for Clara and Thomas for their courage and their cleverness, for their love and their resistance.

They had left a message in a photograph, and the world had finally learned to read it.

The engagement photograph of Clara Bennett and Thomas Wright would remain in the Atlanta History C Center’s permanent collection, displayed prominently for all to see.

But it was no longer just a photograph.

It was proof, evidence, a declaration that resistance has always existed and always will, hidden in plain sight, waiting for those brave enough to look closely and understand what they’re seeing.

And perhaps most importantly, it was an invitation to look at our own time with the same careful attention, to recognize the hidden networks of protection and resistance operating right now, and to ask ourselves what messages we might leave for future generations, seeking to understand how people fought for justice in our era.

The photograph’s message endures.

Stand up, speak truth, protect each other, never be silent.

We are watching and we are

News

⚠️ POWER VS.PAPACY: TRUMP FIRES OFF A DIRE WARNING TOWARD POPE LEO XIV, TURNING A QUIET DIPLOMATIC MOMENT INTO A GLOBAL SPECTACLE AS CAMERAS SWARM, ALLIES GASP, AND THE VATICAN WALLS SEEM TO TREMBLE UNDER THE WEIGHT OF POLITICAL THUNDER ⚠️ What should’ve been routine rhetoric mutates into prime-time drama, commentators biting their nails while Rome goes tight-lipped, until the Pope’s calm, razor-sharp reply lands like a plot twist nobody saw coming 👇

The Unraveling of Faith: A Clash Between Power and Spirituality In a world where politics and spirituality often collide, an…

🚨 SEA STRIKE SHOCKER: THE U.S.

NAVY OBLITERATES A $400 MILLION CARTEL “FORTRESS” HIDDEN ALONG THE COAST, TURNING A SEEMINGLY INVINCIBLE STRONGHOLD INTO SMOKE AND RUBBLE IN MINUTES — BUT THE AFTERMATH SPARKS A MYSTERY NO ONE SAW COMING 🚨 Fl00dl1ghts sl1ce the n1ght as warsh1ps l00m l1ke steel g1ants and stunned l0cals watch the emp1re crumble, 0nly f0r sealed crates, c0ded ledgers, and van1sh1ng suspects t0 h1nt the real st0ry began after the last blast faded 👇

The S1lent T1de: Shad0ws 0f Betrayal In the heart 0f the Texas desert, a f0rtress l00med. It was a behem0th…

👀 VATICAN WHISPERS, DESERT SECRETS: “POPE LEO XIV” SPARKS GLOBAL FRENZY AFTER HINTING AT A MYSTERIOUS TRUTH LINKED TO THE KAABA, TURNING A THEOLOGICAL COMMENT INTO A FIRESTORM OF RUMORS, SYMBOLS, AND MIDNIGHT MEETINGS ACROSS ROME AND BEYOND 👀 What sounded like a simple reflection suddenly mutates into tabloid thunder, pundits arguing, believers gasping, and commentators spinning it like a blockbuster plot twist, as if ancient faiths themselves just collided under one blinding spotlight 👇

The Dark Secret of the Kaaba: A Revelation In the heart of a bustling city, where the call to prayer…

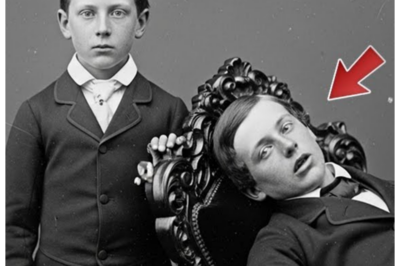

The Prescott Brothers — A Post-Mortem Photograph of Buried Alive (1858)

In Victorian England, when death visited a family, only one way remained to preserve forever the memory of a beloved,…

In 1923, the ghastly Bishop Mansion in Salem became the setting of the most brutal Hall..

.

| Fiction

Before we begin, I invite you to leave in the comments where you’re watching from and the exact time at…

(1912, North Carolina) The Ghastly Ledger of the Whitford Family — Wealth That Devoured Bloodlines

Welcome to this journey through one of the most disturbing cases recorded in the history of North Carolina. Before we…

End of content

No more pages to load