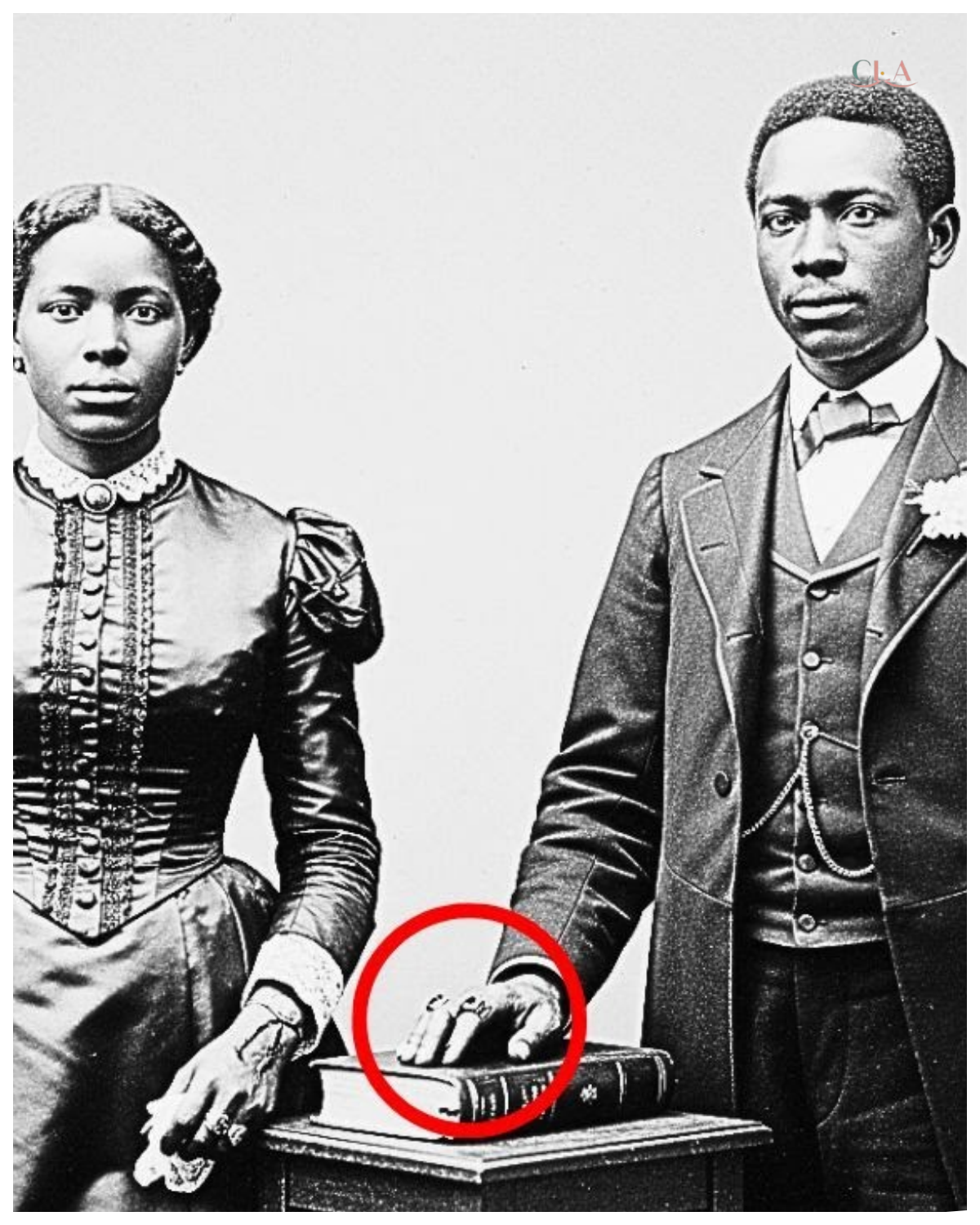

It was just a wedding photo until you zoom in on the groom’s hand.

Dr.

Marcus Chen had been the chief conservator at the Atlanta History Center for nearly 20 years, and he thought he’d seen every type of Civil War era photograph that existed.

The museum’s collection contained thousands of images from the 1860s and 1870s.

Each one a small window into a turbulent period of American history.

But the photograph that arrived on his desk on a gray morning in January 2024 was different from anything he’d encountered before.

It had come from the estate of Helen Morrison, a 93-year-old woman who had recently passed away in Atlanta.

Helen had been a school teacher and amateur genealogologist who had spent decades collecting artifacts related to African-American history in Georgia.

Her will had specified that her entire collection should be donated to the Atlanta History Center.

The photograph was in remarkable condition, protected by being stored in an acid-free envelope inside a wooden box.

It measured approximately 6 by 8 in and was mounted on thick cardboard backing typical of professional photography studios from the post civil war era.

Marcus carefully lifted the photograph from its protective sleeve and placed it under his examination lamp.

The image showed a wedding scene taken in what appeared to be a photographer’s studio.

The backdrop was painted to look like an elegant parlor with columns and draped curtains creating an illusion of wealth and refinement.

The couple stood in the center of the composition, both dressed in their finest clothes.

The bride wore a dark dress with a high collar and long sleeves decorated with delicate lace at the cuffs.

Her hair was styled elaborately, pulled back with what appeared to be small flowers or ribbons woven through the braids.

The groom stood beside her, tall and dignified in a dark suit with a vest and a white shirt with a high collar.

His jacket was buttoned formally, and a watch chain was visible across his vest.

Both the bride and groom were African-American and both stared directly at the camera with expressions of solemn pride.

Marcus noted the photographers’s stamp on the bottom of the cardboard backing.

Sterling and Associates, Atlanta, Georgia, 1871.

While that date was significant, just 6 years after the end of the Civil War, during the brief period of reconstruction, when African-Americans in the South were beginning to build lives as free people, the composition was formal and carefully arranged.

A small table beside them held a Bible.

The groom’s right hand rested on the Bible, and his left hand hung at his side.

It was a beautiful photograph, dignified and moving.

Marcus began his standard assessment, noting the slight fading around the edges.

Then he noticed something about the groom’s hand, the one resting on the Bible.

There was something unusual about it that caught his eye even without magnification.

Marcus reached for his magnifying glass and leaned in closer.

What he saw made his breath catch in his throat.

Under magnification, the groom’s hand revealed details that were invisible to the casual observer.

The skin showed what appeared to be scarring.

Irregular patches of lighter tissue suggesting old injuries, likely from shackles or chains.

But what had caught Marcus’ attention was the ring on the groom’s left hand.

Wedding rings were not uncommon in post civil war photographs, but this one looked different.

Even in the sepia tones of the old photograph, Marcus could see that the ring’s surface had an unusual texture.

It wasn’t smooth and polished like gold or silver typically appeared in photographs from this era.

Instead, it had a rough, almost hammered appearance with visible irregularities in the surface.

The ring also seemed darker than it should be.

Not the bright reflection that gold would create under studio lighting and not the softer gleam of silver.

It was almost black with highlights that suggested metal, but of a different quality than precious metals.

Marcus pulled out his digital camera and took several highresolution photographs of the image, focusing particularly on the groom’s hand in the ring.

He uploaded the images to his computer and used specialized enhancement software to bring out as much detail as possible.

As the image filled his screen, enlarged to many times its original size, Marcus felt his pulse quicken.

The ring surface showed what looked like forge marks, the kind of irregular texture that came from hand hammering metal.

And the color was definitely wrong for gold or silver.

It looked like iron or steel, dark and matte.

But why would a groom wear an iron ring at his wedding? Iron wasn’t used for jewelry in the 1870s, except in very specific circumstances.

Yet, this ring, despite being made of what appeared to be iron, showed signs of careful craftsmanship.

Marcus zoomed in further on the ring surface.

The enhancement software brought out details that would have been completely invisible in the original photograph.

Along the outer edge of the ring, he could make out what appeared to be a repeating pattern.

small indentations or marks that formed a chain-like design around the band.

A chain pattern on an iron ring worn by a formerly enslaved man at his wedding in 1871.

Marcus sat back from his computer screen, his mind racing.

He’d read about this practice in historical journals, formerly enslaved people taking the physical instruments of their bondage and transforming them into symbols of love and commitment.

The ring wasn’t just made of iron.

It was made from iron chains, actual shackles and chains from slavery, melted down and reformed into wedding bands.

This practice had deep symbolic significance during reconstruction, representing transformation from bondage to freedom, from forced separation to chosen commitment.

Marcus needed to know more.

Who were these people? What were their names? And most importantly, did the ring itself still exist somewhere? Marcus began his investigation by examining the photograph’s backing more carefully.

In addition to the photographers’s stamp, someone had written in faded pencil, David and Clara married November 18th, 1871.

The handwriting was elegant, probably added years after the photograph was taken.

Marcus felt grateful for whoever had taken that care.

Without those names and that date, the couple might have remained anonymous forever.

He turned to the museum’s genealological databases, which maintained extensive records of African-American families in Georgia during reconstruction.

Marcus entered David and Clara with the marriage date of November 18th, 1871.

The search took several minutes, then results appeared.

David Freeman, age approximately 28, married Clara Washington, age approximately 24.

on November 18th, 1871 in Atlanta, Georgia.

The marriage was registered at Friendship Baptist Church and recorded in the Fulton County Marriage Register.

Marcus felt a surge of excitement.

He’d found them.

The 1870 census listed David Freeman as a blacksmith living in Atlanta.

His birthplace was listed as Georgia, and the census noted that he could read and write, unusual for someone who would have been enslaved just 5 years earlier.

Clara Washington appeared in the same census as a domestic worker, also born in Georgia, also literate.

She was listed as living in a boarding house for African-American women on Decar Street.

Freriedman’s bureau records provided more information.

Marcus found David Freeman’s entry from 1865.

David, age approximately 22, formerly enslaved by Robert Freeman, Clark County, Georgia.

Occupation, blacksmith, has scars on wrists and ankles from extended periods and chains.

The scars Marcus had noticed in the photograph weren’t just from hard labor.

They were from being restrained for so long that permanent damage occurred.

Clara’s record was equally revealing.

B.

Clara, age approximately 18, formerly enslaved by Thomas Washington, Fulton County.

Literate, learned to read from Washington family children, seeking family members, mother Sarah, brothers Thomas and James, whereabouts unknown.

Like so many formerly enslaved people, Clara had been separated from her family.

The notation appeared in thousands of Freriedman’s Bureau records, people desperately searching for parents, siblings, children who had been sold away.

Marcus also discovered that Clara had been married before during slavery to a man named Joseph, who had been conscripted by Confederate forces and never returned.

Her marriage to David in 1871 wasn’t just a beginning.

It was a second chance after loss and trauma.

He found references to David’s blacksmith shop in Atlanta City directories from the early 1870s.

Freeman, David Colored, a blacksmith shop on Decar Street near the railroad depot.

Most significantly, Marcus found an 1872 article in the Atlanta Advocate describing David’s work.

Mr.

Freeman has become known for creating wedding bands from iron that once bound us, transforming symbols of oppression into symbols of love and freedom.

Marcus discovered that David Freeman’s work creating rings from slave chains had become wellknown in Atlanta’s African-American community during the early 1870s.

His blacksmith shop on Decar Street had become a gathering place and a center for this transformative practice.

An 1873 article in the Atlanta Advocate provided details.

Mr.

Freeman’s forge has become known throughout our community for his special craft.

Couples planning to marry often bring him pieces of iron chains or shackles from their time in bondage.

He has performed the service for more than 50 couples since establishing his shop.

50 couples by 1873.

That meant David was creating these rings regularly, several each month during busy wedding seasons.

Marcus found a letter David himself had written in 1874 to a minister in Savannah who had inquired about the practice.

The letter explained David’s process in philosophy.

When people bring me the iron that once held them in bondage, they are trusting me with their pain and their hope.

Each ring requires four to six hours of work.

I do not charge money for this service.

This is not business.

This is ministry.

The letter continued with technical details.

The iron from chains is often poor quality.

I must heat it many times, folding and hammering it to remove impurities and strengthen it.

Some people want the hammered texture visible, showing the work that went into transforming it.

Others want it smooth and polished, showing that the painful past can be refined into beauty.

David also described what happened during the ring-making process.

People often stay and watch while I work.

They tell me their stories about being chained as punishment, about seeing loved ones in chains, being sold away.

These are hard stories to hear, but I listen.

The ring must contain not just the iron, but also the witness to what was endured.

A stingy church marriage registers from several Atlanta churches noted ring made by David Freeman or rings from chains forged by brother Freeman next to coup’s names throughout the 1870s and 1880s.

One entry particularly moved Marcus in the Wheat Street Baptist Church register from 1872.

Married August 3rd, Samuel Jenkins and Elizabeth Porter.

Rings made by brother Freeman from chains that had bound both bride and groom when enslaved on the same plantation, separated by sale in 1858, reunited after emancipation, now joined in holy matrimony.

Marcus discovered that David’s practice had inspired other blacksmiths.

Letters between African-American community leaders mentioned similar work happening in Savannah, Charleston, New Orleans, and Richmond.

The practice was spreading, becoming a tradition across the South.

The rings represented not just personal love but political resistance.

A declaration that African-Americans would build families that no one could destroy using the very instruments meant to enslave them as foundations for their freedom.

Marcus wanted to understand the day that photograph was taken.

He found the answer in the diary of Reverend Isaiah Grant whose personal papers had been digitized and made available through the Atlanta University Center archives.

Reverend Grant’s diary entry from November 18th, 1871 was extensive.

Today I had the profound honor of joining in holy matrimony David Freeman and Clara Washington.

The ceremony took place at Friendship Baptist Church at 2:00.

More than 100 people attended, nearly filling our sanctuary, a testament to the respect this couple has earned in our community.

The Reverend described the ceremony in detail.

Brother David stood at the altar in a fine suit he had saved for months to purchase.

Sister Clara wore a dress of dark blue silk that she had sewn herself.

Both carried themselves with dignity that moved many to tears, remembering how recently we were denied even the basic right to legal marriage.

And then came the moment captured in the photograph.

When the time came for the exchange of rings, Brother David presented a ring he had forged himself from iron chains that had once bound him.

Sister Clara wept as he placed it on her finger, and there was not a dry eye in the church.

The reverend’s reflection was powerful.

I spoke to the congregation about the meaning of this ring in this marriage.

Just as brother David had taken chains and transformed them into a ring, so too are we as a people transforming our bondage into a foundation for freedom.

This marriage is not just a joining of two individuals, but a declaration.

We are free.

We are human.

We are worthy of love and dignity.

After the ceremony, the couple and their guests walked from the church to Sterling and Associates photography studio, a walk through downtown Atlanta that was itself a statement.

A black couple in wedding clothes surrounded by their community, walking openly through streets where they would have been enslaved just six years earlier.

Reverend Grant described the photography session.

At the studio, Mr.

Sterling treated them with utmost respect.

Brother David insisted that his hand rest on the Bible and that his wedding ring be clearly visible.

He said he wanted future generations to see the ring and understand what it represented.

The celebration afterward continued into the evening with music, food, and dancing.

Reverend Grant’s final reflection captured the day’s significance.

Brother David and Sister Clara’s wedding reminds us that love is an act of resistance.

To choose to love, to commit, to build a family in the face of all that would destroy us.

This is revolutionary.

This is how we win.

Marcus was moved by the reverend’s words written 153 years ago, but still resonant today.

While David’s work as a blacksmith left tangible traces in historical records, Clara’s life was harder to track.

But Marcus was determined to understand her story fully.

He found Clara’s Freriedman’s bureau testimony from 1865 recorded by a bureau agent.

Clara states she was born on the Washington plantation in Fulton County approximately 1847.

She was separated from her mother Sarah and brothers Thomas and James in 1859 when they were sold to a traitor bound for Mississippi.

She was kept on the Washington plantation to work in the house.

She reports being taught to read by the Washington children, though this was against Mr.

Washington’s will, who beat her severely when he discovered her literacy.

Clara had also registered a previous marriage.

Clara states she was married according to slave custom to a man named Joseph in 1863.

Joseph was conscripted to work on Confederate fortifications in 1864 and never returned.

Clara does not know if he is living or dead.

This revelation recontextualized everything.

Clara’s marriage to David in 1871 was a second chance at love after loss and uncertainty.

Marcus found more about Clara and church records.

She had joined Friendship Baptist Church in 1866 and quickly became active.

church meeting.

Minutes from 1867 1870 mentioned her repeatedly organizing literacy classes for formerly enslaved adults, collecting funds for families whose homes had been burned by white terrorists, testifying about violence she had witnessed.

In a particularly moving entry from 1869, the church minutes recorded, “Sister Clara spoke to the congregation about her continued search for her mother and brothers.

She asked for prayers, stating that despite her sorrow, she holds faith that families torn apart will be reunited through God’s grace.

” Marcus found no evidence that Clara ever found her family.

The search continued for years, but they had vanished into slavery and war, but Clara hadn’t let that loss destroy her.

She’d built a new life and eventually found love with David.

Most significantly, Marcus discovered that Clara had testified before a congressional committee in 1870, investigating violence against African-Americans in Georgia.

Her testimony was powerful.

We are told, “We are free, but we are not free to live without fear.

We build and they burn down what we build.

We try to vote and they beat us, but we will not give up.

We will continue to build, continue to learn, continue to fight for the freedom that is rightfully ours.

This was the woman who married David Freeman in November 1871.

A survivor, an activist, a woman who refused to be broken.

When she and David exchanged rings forged from slave chains, they were declaring their survival and their determination to build a life together.

Marcus traced David and Clara’s lives forward through census records.

The 1880 census showed them still living in Atlanta on Decar Street.

David was listed as a blacksmith, age 37.

Clara was listed as a seamstress, age 34.

And there were two children, Robert, age 6, and Sarah, age three.

Marcus felt joy at this discovery.

They’d had children.

They’d built the family they’d hoped for.

The 1900 census showed them still together, now in their 50s.

Their son, Robert, was listed as a teacher at a colored school.

Their daughter, Sarah, was listed as a dress maker, working alongside her mother.

Marcus found Robert Freeman’s name and records from Atlanta University.

Robert had graduated in 1895 and had become an educator, teaching mathematics at a school for African-American children.

Sarah Freeman appeared in city directories as a dress maker and later as the owner of a small shop on Auburn Avenue.

She’d become a successful businesswoman and respected community member.

David’s obituary from 1906 was extensive.

David Freeman, respected blacksmith and community leader, dies at 63.

Mister Freeman was known for his skill as a blacksmith and for his service to newly married couples.

For 40 years, he crafted wedding rings from the chains of slavery.

He created rings for hundreds of couples and never charged for this service, considering it his ministry.

The obituary continued, “He has survived by his beloved wife, Clara, his son, Robert, his daughter Sarah, six grandchildren, and the hundreds of couples whose marriages were blessed by his work.

” Clara lived another 15 years.

Her 1921 obituary read, “Clara Freeman, age 75, pioneer and pillar of community.

Mrs.

Freeman was born into slavery and lived to see her grandchildren educated and successful.

She was known for her literacy work and for her testimony before Congress about violence against colored citizens.

She and her late husband David were married for 35 years and were considered one of the founding couples of Atlanta’s free colored community.

Marcus found one final document, a 1920 letter from Sarah Freeman to a museum offering to donate her parents’ wedding photograph and Clara’s ring.

My father made hundreds of these rings for couples in our community.

He told me once that every ring was an act of defiance, taking what was meant to enslave us and transforming it into something that celebrated our humanity.

He said that as long as people remembered what these rings meant, slavery would never truly win.

Ah, the letter concluded, I offer these items in hopes that future generations will understand what my parents endured and what they built in spite of that endurance.

Marcus wondered if any of David Freeman’s rings had survived into the present day.

He began reaching out to museums with African-American history collections across the South.

Most responses were negative.

But then Dr.

Angela Price, a curator at a small museum in Savannah, emailed, “We have three rings in our collection that match your description.

They were donated by different families over the years, all with similar stories.

Rings made from slave chains worn at weddings in the 1870s and 1880s.

Would you be interested in examining them?” Marcus was on a plane to Savannah 2 days later.

The rings were extraordinary.

Each was different in size and detail, but all shared the same essential characteristics.

dark iron, hammered texture, evidence of careful handcrafting.

They were heavier than modern rings, substantial, showing the patina of age.

Dr.

Price provided documentation for each ring.

The first had been donated in 1968 by a woman whose great-grandparents had been married in Savannah in 1873.

The second came from a family whose ancestors had married in 1879.

The third had been found during house renovations in the 1990s with a note, married 1876.

Rings from chains, never forget.

Marcus examined each ring under magnification.

The hammer marks were clearly visible, small facets where metal had been struck repeatedly.

The surface showed where different pieces of iron had been welded together through forging.

Two rings had decorative elements, one with a chain pattern engraved around the edge, another with tiny crossed hammers, perhaps the maker’s signature.

Dr.

Price had arranged materials analysis by a university engineering department.

A metallurgist named Dr.

James Woo examined them using X-ray fluorescent spectroscopy.

Dr.

Woos findings confirmed Marcus’ theories.

These rings are definitely rot iron, consistent with mid-9th century American iron.

The structure shows repeated folding and hammering, how a blacksmith would consolidate multiple pieces of scrap iron into one object.

He showed Marcus microscope images.

These lines are boundaries between different pieces of iron that were forge welded together.

Each ring probably started as three or four separate pieces.

Links from chains, pieces of shackles, heated to nearly 2500° and hammered until they fused.

Dr.

Dr.

Woo concluded, “What’s remarkable is the craftsmanship.

Forging iron into a ring is challenging.

These show skilled work.

Whoever made them knew exactly what they were doing.

” Marcus thanked Dr.

Woo and returned to the museum.

As they packed the rings carefully, Dr.

Price asked what he planned to do with his research.

I want to create an exhibition, Marcus said.

I want people to understand what these rings represented.

Acts of love and resistance, declarations of freedom and dignity.

3 months after beginning his research, Marcus received an unexpected package.

Inside was a letter.

Dr.

Chen, I’m writing after seeing news coverage of your research.

My name is Dorothy Freeman Watson.

I’m the great great granddaughter of David and Clara Freeman.

My family has preserved the ring that David made for Clara, which she wore for 35 years.

After seeing your work and understanding how important this history is, we have decided to donate the ring to the Atlanta History Center.

Marcus’ hands shook as he opened the small box inside the package.

Wrapped in tissue paper was an iron ring, dark, hammered, irregular, beautiful.

Clara’s ring, the one visible in the 1871 photograph, worn through 35 years of marriage, preserved through five generations.

He examined it carefully.

The ring showed all the characteristics he’d studied in the Savannah examples, the hammered texture, the forge welding marks, the deliberate irregularities that spoke of handcrafting.

But this ring had documented providence, a clear chain of custody connecting it directly to the photograph and to David Freeman’s work.

Along the inner surface, Marcus found tiny marks he hadn’t been able to see in the photograph.

Letters stamped into the iron.

DF1871, David Freeman’s signature and the year he’ created it.

Marcus contacted Dorothy Freeman Watson to learn more.

She shared family stories passed down through generations.

My grandmother told me that David made Clara’s ring from pieces of the chains that had held him on the Freeman plantation.

He saved those pieces after emancipation, keeping them for years before he felt ready to transform them.

When he finally made Clara’s ring in 1871, it was both a personal memorial and a promise that their love would be stronger than anything that had tried to break them.

Dorothy continued, “Chara wore that ring every day of her married life.

” After David died in 1906, she continued wearing it until her own death 1921.

She told her daughter Sarah that the ring represented everything they’d overcome and everything they’d built together.

Sarah preserved it, then passed it to her daughter, who passed it to me.

“Five generations of women in our family have been guardians of this ring.

” She paused, then added.

But it’s time for it to be shared.

This story belongs to more than just our family.

It belongs to everyone who needs to understand that love can transform even the worst suffering into something beautiful and enduring.

Marcus arranged for the ring to be formally accessioned into the museum’s collection.

It would become the centerpiece of an exhibition he was already planning, an exhibition that would tell David and Clara’s story and the larger story of this remarkable tradition of transformation and resistance.

The ring that had begun as chains of slavery that had been transformed by fire and hammer into a circle of love would now serve its final purpose, teaching future generations about survival, resistance, and the unbreakable human capacity for hope.

8 months after Marcus first examined David and Clara’s wedding photograph, the Atlanta History Center opened, Forged in Freedom: Wedding Rings from Slave Chains.

The exhibition opened on November 18th, 2024, exactly 153 years after David and Clara’s wedding.

The centerpiece was their wedding photograph enlarged to 5t tall.

Beside it, in a climate controlled case with dramatic lighting, sat Clara’s ring.

The actual object from the photograph preserved through five generations.

Text panels explained what visitors were seeing.

This photograph shows David and Clara Freeman on their wedding day, November 18th, 1871.

The ring on David’s hand is made from iron slave chains.

David was a blacksmith who transformed instruments of oppression into symbols of love, creating rings for hundreds of couples in Atlanta’s African-American community during reconstruction.

The exhibition included the three rings from Savannah, each with its own story.

Interactive displays showed the ring making process.

Audio recordings featured a descendants sharing family stories passed down through generations.

One section focused specifically on David Freeman’s life.

His letter explaining his philosophy, Reverend Grant’s diary entry, newspaper articles documenting his practice, and large photograph details showed David’s scarred hands, the ring’s texture, the couple’s dignified expressions.

Another section contextualized the practice within slavery, emancipation, and reconstruction.

It explained how marriages between enslaved people had no legal recognition, how families were deliberately separated, and how the right to legal marriage was one of the first freedoms formerly enslaved people exercised.

The exhibition addressed the ongoing legacy, including contemporary couples who had chosen iron rings as tributes to their ancestors.

On opening day, Marcus watched visitors reactions.

Many walked past initially, seeing just another old portrait.

Then they would read the text panel, and their expressions would change.

They would step closer, study David’s hand, then spend sometimes an hour in the exhibition.

An elderly black woman approached Marcus, tears on her face.

My grandmother told me stories about rings like this.

I thought it was just a story, but it was real.

She looked at David and Clara’s photograph.

They look so dignified, so proud.

After everything they went through, they stood there and said, “We are worthy of love, worthy of being remembered.

That’s what this photograph is saying.

” A young couple stopped together.

“Can you imagine?” The woman said, “Being able to take something used to hurt you and transform it into something beautiful.

That’s not survival.

That’s triumph.

” The exhibition became one of the museum’s most popular displays.

Media coverage spread the story nationally.

Scholars began researching the practice more systematically.

Marcus often stood near the photograph, thinking about David and Clara.

They had survived unimaginable trauma, built lives of dignity, raised educated children, contributed to their community.

But perhaps David’s most lasting contribution was those rings.

Hundreds of them, each transforming pain into beauty, bondage into freedom, chains into circles of love that would endure for generations.

News

🌲 IDAHO WOODS HORROR: COUPLE VANISHES DURING SOLO TRIP — TWO YEARS LATER FOUND BURIED UNDER TREE MARKED “X,” SHOCKING AUTHORITIES AND LOCALS ALIKE ⚡ What started as a quiet getaway turned into a terrifying mystery, as search parties scoured mountains and rivers with no trace, until hikers stumbled on a single tree bearing a carved X — and beneath it, a discovery so chilling it left investigators frozen in disbelief 👇

In August 2016, a pair of hikers, Amanda Ray, a biology teacher, and Jack Morris, a civil engineer, went hiking…

⛰️ NIGHTMARE IN THE SUPERSTITIONS: SISTERS VANISH WITHOUT A TRACE — THREE YEARS LATER THEIR BODIES ARE FOUND LOCKED IN BARRELS, SHOCKING AN ENTIRE COMMUNITY 😨 What began as a family hike into Arizona’s notorious mountains turned into a decade-long mystery, until a hiker stumbled upon barrels hidden in a remote canyon, revealing a scene so chilling it left authorities and locals gasping and whispering about the evil that had been hiding in plain sight 👇

In August of 2010, when the heat was so hot that the air above the sand shivered like coals, two…

⚰️ OREGON HORROR: COUPLE VANISHES WITHOUT A TRACE — 8 MONTHS LATER THEY’RE DISCOVERED IN A DOUBLE COFFIN, SHOCKING AN ENTIRE TOWN 🌲 What began as a quiet evening stroll turned into a months-long nightmare of missing posters and frantic searches, until a hiker stumbled upon a hidden grave and police realized the truth was far darker than anyone dared imagine, leaving locals whispering about secrets buried in the woods 👇

On September 12th, 2015, 31-year-old forest engineer Bert Holloway and his 29-year-old fiance, social worker Tessa Morgan, set out on…

🌲 NIGHTMARE IN THE APPALACHIANS: TWO FRIENDS VANISH DURING HIKE — ONE FOUND TRAPPED IN A CAGE, THE OTHER DISAPPEARS WITHOUT A TRACE, LEAVING INVESTIGATORS REELING 🕯️ What started as an ordinary trek through the misty mountains spiraled into terror when search teams stumbled upon one friend locked in a rusted cage, barely alive, while the other had vanished as if the earth had swallowed him, turning quiet trails into a real-life horror story nobody could forget 👇

On May 15th, two friends went on a hike in the picturesque Appalachian Mountains in 2018. They planned a short…

📚 CLASSROOM TO COLD CASE: COLORADO TEACHER VANISHES AFTER SCHOOL — ONE YEAR LATER SHE WALKS INTO A POLICE STATION ALONE WITH A STORY THAT LEFT OFFICERS STUNNED 😨 What started as an ordinary dismissal bell spiraled into candlelight vigils and fading posters, until the station doors creaked open and there she stood like a ghost from last year’s headlines, pale, trembling, and ready to tell a truth so unsettling it froze the entire room 👇

On September 15th, 2017, at 7:00 in the morning, 28-year-old teacher Elena Vance locked the door of her home in…

🌵 DESERT VANISHING ACT: AN ARIZONA GIRL DISAPPEARS INTO THE HEAT HAZE — SEVEN MONTHS LATER SHE SUDDENLY REAPPEARS AT THE MEXICAN BORDER WITH A STORY THAT LEFT AGENTS STUNNED 🚨 What began as an ordinary afternoon spiraled into flyers, helicopters, and sleepless nights, until border officers spotted a lone figure emerging from the dust like a mirage, thinner, quieter, and carrying answers so strange they turned a missing-person case into a full-blown mystery thriller 👇

On November 15th, 2023, 23-year-old Amanda Wilson disappeared in Echo Canyon. And for 7 months, her fate remained a dark…

End of content

No more pages to load