The auction house in Boston smelled of old paper and varnished wood.

Dr.Elizabeth Morgan had spent the better part of her career examining historical photographs, but something about the image in her hands made her pause.

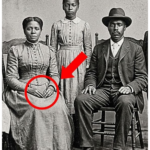

It was a cabinet card from 1895 mounted on thick cardboard that had yellowed with age, but remained remarkably intact.

The photograph showed seven people, a man and woman, standing behind five children arranged by height.

The smallest, no more than 5 years old.

They wore their finest clothes.

The father’s suit, though simple, was pressed and clean.

The mother’s dress had delicate buttons running down the front, and her hair was styled with obvious care.

The children stood perfectly still, as photography required in that era, their expressions serious, but not somber.

It was, by all accounts, an ordinary family portrait from the late 19th century.

Elizabeth had been called to authenticate a collection of African-American historical photographs donated to the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Most were faded, damaged, or poorly preserved.

This one was different.

The clarity was exceptional.

Every fold in the fabric, every strand of hair, every detail of their faces had survived more than a century with unusual sharpness.

She placed the photograph under the magnifying lamp on her desk.

The light revealed textures invisible to the naked eye, the weave of the father’s jacket, a small tear in the backdrop behind them, even the grain of the wooden floor they stood upon.

Elizabeth began her standard documentation process, measuring dimensions, noting the photographers’s stamp on the back, recording the cards stockck type.

[music] Then she saw them.

At first, she thought it was a defect in the print.

Irregular dark lines across the father’s hands where they rested on the shoulder of his oldest son.

She adjusted the lamp, bringing the image closer.

Not printing defects.

The lines had depth, texture, dimension.

She moved to the mother’s hands, folded gracefully at her waist.

There, too.

Marks that seemed to tell a story the formal pose tried to conceal.

Elizabeth reached for her digital microscope.

As the image filled her computer screen at 10 times magnification, her breath caught.

These weren’t just marks.

They were scars.

Deep old scars that had healed decades before this photograph was taken.

Scars that spoke of a past this family had dressed up, composed themselves, and stood before a camera to leave behind.

Elizabeth spent the next 3 hours examining every inch of the photograph.

She documented the scars with clinical precision, taking measurements, noting patterns, comparing them to medical archives of historical injuries.

The father’s wrists bore circular marks, consistent and symmetrical.

They wrapped around both wrists like permanent bracelets of damaged tissue.

His palms showed linear scars, some crossing each other, creating a map of old wounds.

The mother’s hands told a different but equally disturbing story.

Her fingers appeared slightly bent, as if they had been broken and healed incorrectly.

The skin across her palms was textured differently from the surrounding tissue, smoother in some places, rougher in others.

Along the backs of her hands ran thin, raised lines that disappeared into the sleeves of her dress.

Elizabeth pulled up her database of 19th century labor practices.

She had studied this period extensively, the decades following the Civil War, when 4 million formerly enslaved people began building new lives.

The scars she was looking at didn’t come from ordinary work accidents.

They were too specific, too patterned, too extensive.

She zoomed in on the father’s face.

His expression was dignified, almost defiant.

[music] His eyes looked directly at the camera with unwavering steadiness.

Whatever he had endured, he had survived it.

He had built a family.

He had saved enough money to afford this photograph.

An expensive luxury in 1895.

This wasn’t just a portrait.

It was a declaration.

Elizabeth checked the photographers’s mark on the back.

Jay Harrison and Sons, Richmond, Virginia, 1895.

Richmond, the former capital of the Confederacy, a city still rebuilding 30 years after the war ended.

She made a note to research photographers in that area to see if there were records of who had their pictures taken and why.

But first, she needed to understand these scars.

She reached for her phone and called Dr.

Marcus Webb, a colleague who specialized in forensic historical analysis.

When he answered, she didn’t bother with pleasantries.

Marcus, I need you to look at something.

How soon can you get to my office? What kind of something? The kind that changes what we thought we knew about a photograph from 1895.

There was a pause on the other end.

I can be there in 20 minutes.

Marcus arrived carrying his laptop and a leather case filled with specialized equipment.

He was a tall man in his early 50s with wire- rimmed glasses that he constantly adjusted when concentrating.

Elizabeth had the photograph displayed on her largest monitor when he walked in.

“Show me,” he said, setting his equipment on the table.

Elizabeth guided him through her findings, pointing out each scar, each mark, each irregularity.

Marcus leaned in close, his face inches from the screen.

He said nothing for several minutes, occasionally zooming in on different sections, comparing angles, making mental notes.

Finally, he sat back.

Do you know what you have here? I have theories.

These aren’t theories anymore, Elizabeth.

Look at the wrist marks on the father.

See how uniform they are? That’s from restraints.

Metal restraints worn for extended periods, probably years.

The skin healed around them, creating permanent indentations.

And here, he pointed to the father’s palms.

These are tool marks.

Agricultural tools most likely.

Cotton hooks, harvest blades, implements used in fieldwork.

Elizabeth felt her stomach tighten.

She had suspected, but hearing it confirmed made it real.

Marcus moved to the mother’s hands.

Her injuries are different, but equally telling.

These bent fingers, that’s from repetitive strain combined with inadequate healing.

When fingers break and you’re forced to keep working, they set incorrectly.

And these marks across her palms.

See how they’re concentrated in the center? That’s from handling rough materials repeatedly.

Cotton bowls perhaps, or hemp rope.

They were enslaved, Elizabeth said quietly.

It wasn’t a question.

Almost certainly the abolition happened in 1865.

This photograph is from 1895, 30 years later.

If they were young when freed, teenagers perhaps, these scars would have had time to fade somewhat, but never completely disappear.

They’re permanent records.

Elizabeth looked at the children in the photograph.

The oldest appeared to be around 15, the youngest, no more than five.

The children were born free.

Yes, after emancipation, this family, Marcus gestured at the screen.

They survived, built a life, had children who never knew chains.

But the parents carried these marks forever.

Why would they have this photograph taken? Elizabeth wondered aloud.

Why preserve evidence of what they went through? Maybe, Marcus said softly.

They weren’t trying to preserve the evidence.

Maybe they were trying to prove they had moved beyond it.

Elizabeth couldn’t let it go.

That night, she sat at her kitchen table with her laptop, searching through digitized records from Richmond, Virginia.

The 1890 census had been destroyed in a fire, which made tracking people from that era incredibly difficult.

But there were other sources.

City directories, property records, church registries, newspaper archives.

She started with the photographer.

Jay Harrison and Sons had been a prominent photography studio in Richmond from 1880 to 1910.

[music] Their business records, miraculously, had been preserved by a local historical society.

Elizabeth requested access and received a scanned ledger book 2 days later.

The ledger listed clients by date, name, and type of photograph ordered.

Most entries were simple.

John Smith, single portrait, or Williams family, group sitting.

But as Elizabeth scrolled through the entries from 1895, one caught her attention.

Family of seven, cabinet [music] card, payment in full, August 1895.

No name, just family of seven.

She cross referenced this with other documents from that period.

In 1895, having a professional photograph taken was expensive, roughly equivalent to a week’s wages for most workers.

For a formerly enslaved family to afford this meant serious saving, significant sacrifice.

Elizabeth expanded her search to Richmond’s African-American community records.

Several churches had maintained detailed membership logs.

She found birth records for children born in the 1880s and 1890s, marriage records from the 1870s, property transactions showing formerly enslaved people purchasing land and homes.

One document stood out.

A property deed from 1882 recording the sale of a small plot of land to a man and his wife.

Both listed as colored with no surnames provided, a common practice immediately following emancipation.

The location was on the outskirts of Richmond in an area that had become an enclave for freed people.

Elizabeth studied maps from that era.

The neighborhood had been called Union Hill, and it had housed dozens of families rebuilding their lives.

She found newspaper articles mentioning the community, some sympathetic, many hostile.

Richmond in the 1890s was a city struggling with its past and resisting the future.

Then she found something unexpected, a mention in a church newsletter from 1896, one year after the photograph was taken.

It listed community members who had recently departed for Northern Opportunities.

Among the names, a family of seven.

Elizabeth contacted the historical societies in Philadelphia, New York, and Boston, cities where many African-American families from Virginia had migrated in the late 1890s, seeking better opportunities and escaping increasingly hostile Jim Crow laws.

She sent copies of the photograph, asking if anyone recognized the family or had records that might match.

3 weeks later, she received a response from the Philadelphia Historical Commission.

An archivist named James Chen had been working on a project documenting great migration families.

Not the famous migration of the 1920s, but the smaller, earlier movements of the 1890s.

“I think I found your family,” his email read.

“Or at least their trail,” Elizabeth called him immediately.

James explained that he had been cataloging church records from a historically black congregation in North Philadelphia.

In their membership logs from 1896, he had found an entry for a family matching the photograph’s description, a couple in their 40s with five children.

The church kept detailed records, James explained.

They noted where families came from, what work they did, significant life events.

This family arrived from Richmond in late 1895, just a few months after your photograph was taken.

Do you have names? Elizabeth asked.

First names only for the parents.

The father is listed as Thomas.

The mother is Sarah.

The children’s names are also recorded.

But here’s what’s interesting.

There’s a note in the margin written in different ink added later.

It says, “Family of great dignity and quiet strength.

Both [music] parents bear the marks of their former condition.

” Elizabeth felt chills run down her spine.

Someone noticed the scars.

It appears so.

The church’s pastor at the time was known for documenting the stories of his congregation.

He interviewed families, recorded their histories.

Unfortunately, most of his detailed notes were lost in a fire in 1923, but this marginal comment survived.

What happened to them? The family? James paused.

The records show they were active church members for several years.

Thomas worked as a skilled carpenter.

Sarah took in laundry and sewing.

The children attended school, which was remarkable for that time.

The oldest son’s name appears in high school records from 1899.

And after that, the trail gets harder to follow.

Families move frequently.

Names changed.

Records became scattered.

But I have one more thing to show you.

James sent another file, a newspaper clipping from the Philadelphia Tribune, an African-American newspaper dated 1904.

It was a brief article about a community celebration listing prominent families in attendance.

Among them, Thomas and Sarah, longtime residents known for their contributions to the community’s growth.

Nine years after the photograph, they had not just survived, they had built something lasting.

Elizabeth became obsessed with finding what happened to the five children in the photograph.

She reached out to genealogologists, posted inquiries on historical research forms, and spent hours pouring through school records, marriage certificates, and city directories from Philadelphia in the early 1900s.

The oldest son’s trail was easiest to follow.

His name, she now knew him as Thomas Jr.

, appeared in high school graduation records from 1900, one of only a handful of black students to complete secondary education in Philadelphia that year.

From there, she found a college enrollment record, Howard University, Washington, DC, 1901.

He had studied to become a teacher.

The second child, a daughter named Ruth, married in 1905.

Elizabeth found the marriage certificate, which listed her father’s occupation as carpenter and noted that Ruth herself worked as a seamstress.

The certificate included an address in South Philadelphia in a neighborhood that had been predominantly African-American.

The middle child, a son named Samuel, proved harder to track.

His name appeared sporadically in city directories, always with different occupations, laborer, porter, later a shop owner.

He seemed to have moved frequently within Philadelphia, perhaps seeking better opportunities.

The two youngest children, Mary and Joseph, both born in the early 1890s, had been small children in the photograph.

Elizabeth found their school records, showing regular attendance through 8th grade.

Mary’s name appeared in a church choir roster from 1908.

Joseph’s name showed up in military draft registration cards from 1917 when America entered World War I.

But what struck Elizabeth most was what she found in census records from 1910.

By [music] then, all five children were listed as literate, able to read and write.

In 1910, when more than 30% of black Americans in the South were still illiterate due to lack of educational access, these five children of formerly enslaved parents had all received education.

Thomas and Sarah had done something extraordinary.

Despite carrying the permanent marks of enslavement, despite the economic hardships and racial hostility they faced, they had ensured their children had opportunities they themselves had been denied.

Elizabeth found one more document that brought tears to her eyes.

a property deed from 1908 showing that Thomas had purchased a house in North Philadelphia, not rented, owned, a two-story rowhouse on a quiet street.

The deed listed his occupation as master carpenter [music] and noted that the property was purchased free and clear 43 years after emancipation.

This man, who had once been someone’s property, now owned property himself, and he had done it with hands that bore the permanent scars of what he had survived.

Elizabeth decided the photograph deserved more than historical research.

It needed modern forensic analysis.

She contacted Dr.

Lisa Park, a specialist in historical photograph authentication and digital enhancement at MIT.

Lisa had developed software that could extract details from old photographs that were invisible even under magnification.

Lisa agreed to examine the image, intrigued by its clarity and historical significance.

When Elizabeth arrived at her lab, Lisa had already loaded the photograph into her analysis system.

The image appeared on a massive monitor, every pixel visible.

This is remarkable preservation, Lisa said, adjusting her equipment.

The photographer who took this knew their craft.

The exposure is perfect, the focus sharp, the chemical development precise.

This wasn’t some traveling photographer with basic equipment.

This was a professional studio.

She began running the image through various filters and enhancement algorithms.

I’m looking at the texture of the scars under different wavelengths of light.

Scars reflect light differently than normal skin because the collagen structure is different.

Watch this.

The image shifted as Lisa applied a filter.

Suddenly, the scars on both parents’ hands became startlingly visible, appearing almost three-dimensional.

Elizabeth could see details she had missed before.

The exact width of the marks on Thomas’ wrists, the precise pattern of the linear scars on Sarah’s palms.

These wrist marks, Lisa said, pointing at the screen, are consistent with metal restraints worn for years, not months.

See how the scarring goes deep? That’s from prolonged pressure combined with movement.

Walking, working, struggling against them.

The body tried to heal around the metal, creating these permanent indentations.

She moved to Sarah’s hands.

The damage here is different.

These aren’t from restraints.

Look at the pattern.

The scarring is concentrated in areas of repeated trauma.

The bent fingers suggest breaks that healed while she continued working.

No medical treatment, no time to rest.

The body healed as best it could under impossible conditions.

Lisa ran another analysis, this time focusing on the couple’s faces.

Look at their expressions, the micro expressions, the muscle tension around their eyes and mouths.

They’re not just posing, they’re projecting something.

Determination, maybe.

Pride, certainly.

This wasn’t a casual portrait.

This meant something to them.

Can you date the scars? Elizabeth asked.

Not precisely, but I can estimate how old they are based on the healing patterns.

[music] These scars are at least 25 to 30 years old in this photograph.

If the photo is from 1895, that puts the injuries in the 1860s or earlier, right in line with your theory.

Lisa printed out enhanced versions of the photograph, each highlighting different aspects.

[music] In one version, the scars were clearly visible.

In another, they had been digitally minimized, showing what the family might have looked like without those marks.

The contrast was striking and heartbreaking.

Elizabeth’s research breakthrough came from an unexpected source.

She had posted about the photograph on a genealogy form, including only basic details and asking if anyone had family connections to Philadelphia’s black community in the 1890s.

3 months later, she received a message from a woman named Patricia Johnson.

I think that might be my great great-grandparents.

The message read, “My grandmother used to tell stories about her grandfather, Thomas, who was a carpenter in Philadelphia.

She said he never talked about his life before coming north, but she remembered seeing marks on his hands when she was a little girl.

” Elizabeth’s heart raced as she read the message.

She arranged to meet Patricia at a coffee shop in Philadelphia.

Patricia arrived carrying a worn cardboard box filled with family documents and photographs.

My grandmother passed away in 1989, Patricia explained, opening the box carefully.

She was Ruth’s daughter.

Ruth was one of the children in the photograph.

If this is really them, grandmother Ruth lived to be 93.

She used to tell us stories about her parents, about how hard they worked, how much they sacrificed.

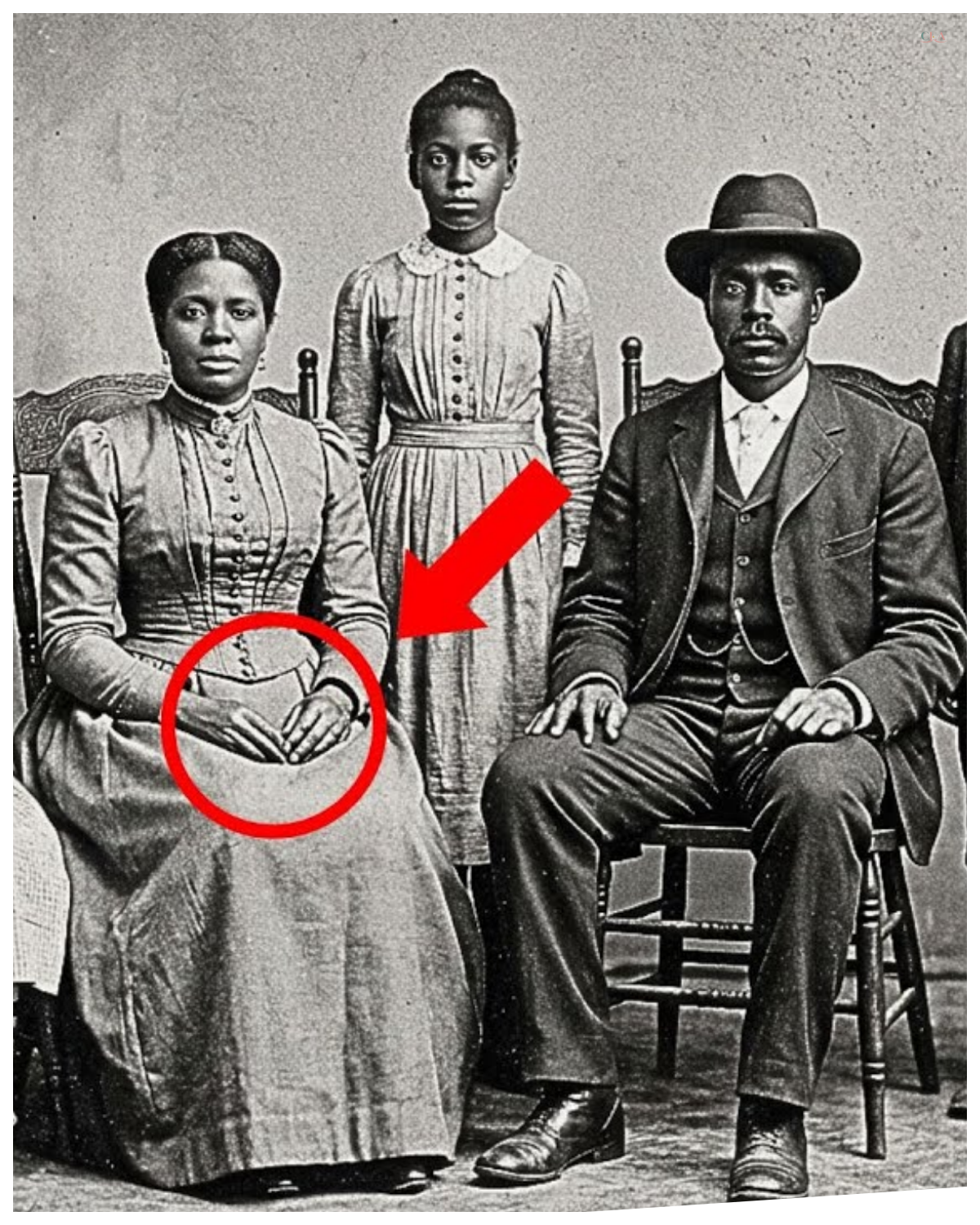

Patricia pulled out a photograph from the 1920s showing an elderly couple sitting on a porch.

This is them, Thomas and Sarah, probably in their 70s here.

See his hands? Elizabeth looked closely.

Even decades later, even in the faded photograph, she could see the marks on Thomas’s wrists.

Grandmother said her father never talked about being enslaved, Patricia continued.

It was like a wall he had built around that part of his life.

But sometimes, she said, he would look at his hands with this expression she couldn’t read.

Not shame exactly, more like remembrance.

Patricia pulled out more documents, death certificates, obituaries, letters.

Sarah had died in 1928 at age 73.

Thomas followed two years later at 78.

Their obituaries in the Philadelphia Tribune described them as pillars of the community and beloved parents and grandparents.

Did your grandmother ever say why they had that photograph taken in 1895? Elizabeth asked.

Patricia nodded slowly.

She said her father told her once that when they finally had enough money saved, he wanted proof that they had made it.

Not proof for the world, proof for themselves.

That photograph was their Declaration of Independence.

30 years late, but finally theirs to claim.

Elizabeth felt tears forming.

Would you be willing to share your family’s story publicly to let people know who these people were, what they survived, what they built? Patricia looked at the 1895 photograph on Elizabeth’s tablet, studying the faces of her ancestors.

[music] They spent their lives trying to move beyond those scars, she said quietly.

But maybe it’s time people knew the truth.

not to focus on what was done to them, but to understand what they overcame.

Six months later, the Massachusetts Historical Society opened a special exhibition titled Visible Histories: Stories Written on the Body.

The 1895 photograph of Thomas and Sarah’s family was the centerpiece, displayed on a large wall with detailed explanations and context.

Elizabeth had worked with Patricia and other descendants to create a comprehensive display.

It included the original photograph, enhanced forensic images showing the scars in detail, historical documents about enslavement and its [music] aftermath, and most importantly, the story of what the family had built.

After 1895, the exhibition opened on a Saturday morning.

Elizabeth stood near the entrance, watching visitors file in.

Some stopped briefly at each display.

Others stood transfixed before the central photograph, reading every word of explanation, studying every detail of the image.

One visitor, an elderly black man, stood before the photograph for nearly 20 minutes.

“Elizabeth noticed tears running down his face.

She approached him gently.

” “My grandfather had marks like those,” he said without turning away from the image, on his wrists, on his back.

He was born in 1858, enslaved until he was 7 years old.

He lived to be 92, but he carried those marks his entire life.

He never talked about them, but we all knew, we all saw.

Throughout the day, similar stories emerged.

Descendants of formerly enslaved people recognized the scars, understood their meaning, shared their own family histories.

The photograph had become more than a historical artifact.

It was a mirror reflecting countless untold stories.

Patricia attended the opening with several family members, including her own grandchildren.

They stood together before the photograph of their ancestors, and Patricia explained who each person was, what they had accomplished, how their sacrifice and strength had rippled forward through generations.

That’s your great great great grandfather Thomas,” she told her youngest grandson, a boy of about eight.

“He built houses with those hands, beautiful houses that are still standing today.

He made sure all his children could read and write.

He saved enough money to buy his own home.

” “And he did all of that, even though he carried those scars forever.

” The boy studied the photograph seriously.

“He looked strong,” he said finally.

“He was,” Patricia replied.

“They both were.

” Local newspapers covered the exhibition.

A reporter from the Boston Globe interviewed Elizabeth about the forensic analysis and historical research.

National media picked up the story.

Within weeks, the photograph had been shared millions of times online.

Each share accompanied by discussions about historical trauma, resilience, and the long shadow of enslavement.

But Elizabeth noticed something else in the responses.

Gratitude.

Person after person thanked her for bringing this family story to light.

For not looking away from the scars, for insisting that what had been survived deserved to be remembered and honored.

Three months after the exhibition opened, Elizabeth received a package from Patricia.

Inside was a leatherbound journal.

Its pages yellowed and fragile.

A note explained, “We found this among my grandmother Ruth’s belongings.

It’s her diary from the 1960s.

There’s an entry I think you should read.

” Elizabeth carefully opened the journal to the marked page.

The entry was dated August 15th, 1963, the same month as the March on Washington.

Ruth would have been in her late ‘7s by then.

The entry read, “Today they are marching in Washington for freedom and rights.

we should have had a century ago.

I’m too old to march, but I remember my father’s hands.

He never spoke of his ears in bondage, but those marks told the story he couldn’t say aloud.

When I was a little girl, I asked him once why he didn’t have them removed.

I’d heard that doctors could sometimes help with scars.

[music] He looked at me with such tenderness and said, “These marks are proof that I survived.

They’re proof that nothing could break me.

And every time I look at them, I remember that I am free.

” I didn’t understand.

Then I thought scars were something to hide, something shameful.

But I understand now.

My father didn’t display those scars, but he didn’t hide them either.

They were part of his truth, part of his story.

He built a good life despite them.

Or perhaps because of them, because they reminded him every day what he had overcome and why he fought so hard to give us better.

I look at my own hands now, unmarked and free, and I think of his.

I raised four children with these hands.

I held grandchildren with them.

I never knew chains or lashes or the sting of forced labor.

Because my father survived with his scars, I lived without them.

That is his legacy.

Elizabeth closed the journal carefully, her throat tight with emotion.

This was what the photograph had been trying to say all along.

Not just a record of suffering, but a testament to survival.

Not just evidence of historical trauma, but proof of impossible strength.

She thought about Thomas and Sarah standing before the camera in 1895, wearing their finest clothes, their children arranged around them.

They had known the photographer would capture everything, including the marks they carried.

They had chosen to take that photograph anyway to create a record that said, “We were enslaved.

We survived.

We built this family.

We are here.

” The truth written on their hands wasn’t just about what had been done to them.

It was about what they had done despite it.

How they had loved, worked, saved, struggled, and persevered until they could stand before a camera and claim their place in history.

Elizabeth returned to her office and looked once more at the photograph displayed on her wall.

Thomas’s hand resting on his son’s shoulder, those scarred fingers, a bridge between a brutal past and a possible future.

Sarah’s dignified expression, her marked hands folded calmly, carrying her truth with quiet strength.

They had left this photograph behind, not as evidence of their suffering, but as proof of their triumph.

And 130 years later, their message had finally been received, understood, and honored.

The scars told a truth no one should have had to carry.

But the photograph told a greater truth that carrying it they had refused to be broken.

They had survived.

They had built.

[music] They had loved.

News

This Forgotten 1912 Portrait Reveals a Truth That Changes Everything We Thought We Knew — and Historians Are Panicking Over What’s Hidden in Plain Sight 🖼️ — It hung unnoticed for over a century, dismissed as polite nostalgia, until one sharp-eyed researcher zoomed in and felt their stomach drop, because the face, the object, the posture all scream a secret no one was supposed to catch, turning a dusty archive into a ticking historical bombshell 👇

This forgotten 1912 portrait reveals a truth that changes everything we knew until now. Dr.Marcus Webb had been working as…

Four Years After The Grand Canyon Trip, One Friend Returned Hiding A Dark Secret

On August 23rd, 2016, 18-year-olds Noah Cooper and Ethan Wilson disappeared without a trace in the Grand Canyon. For four…

California Governor STUNNED as Amazon Slams the Brakes on Massive Expansion — Billions Vanish Overnight and a Golden-Era Promise Turns to Dust 📦 — What was supposed to be a ribbon-cutting victory lap morphs into a political nightmare as Amazon quietly freezes its grand plans, leaving empty lots, stalled cranes, and thousands of “future jobs” evaporating like smoke, while the governor stands blindsided, aides scrambling, and critics whispering that the tech titan just played the state like a pawn 👇

The Collapse of Ambition: A California Nightmare In the heart of California, where dreams are woven into the fabric of…

California Governor FURIOUS as Walmart Slashes Hundreds of Jobs Overnight — Retail Giant’s Brutal Cuts Ignite Political War and Leave Families Reeling 🛒 — One minute paychecks felt safe, the next badges stopped working and managers spoke in rehearsed whispers, as Walmart’s cold-blooded decision detonated across the state like a corporate bombshell, and the governor stormed to the podium red-faced and shaking, promising consequences while stunned workers carried boxes to their cars under gray skies 👇

The Reckoning of California: A Retail Giant’s Fall In the heart of California, the sun dipped below the horizon, casting…

California Governor STUNNED as Tesla Drops the Hammer — Massive Factory Shutdown Sparks Panic, Pink Slips, and a Silicon Valley Meltdown No One Saw Coming ⚡ — One minute it was business as usual, the next the phones were ringing off the hook and security badges were going dark, as Tesla’s shock announcement ripped through Sacramento like an earthquake, leaving lawmakers scrambling, workers stunned, and the governor staring into the cameras with that frozen smile that screams “we did NOT plan for this” 👇

The Shocking Fallout: Tesla’s Shutdown Sophia Miller stood in front of the camera, her expression a mix of disbelief and…

What Really Happened to the Bodies of the Challenger Crew? The Ocean Floor Search, the Sealed Coffins, and the Details NASA Never Wanted the Public to Picture 🚀 — For decades they told us a clean, heroic story wrapped in flags and speeches, but behind the memorials divers were descending into black water, recovering fragments in silence while officials spoke in careful half-sentences, and now those forgotten recovery logs read less like history and more like a nightmare the agency prayed would stay buried forever 👇

The Silent Descent: A Tale of Courage and Catastrophe On a fateful January morning in 1986, the world held its…

End of content

No more pages to load