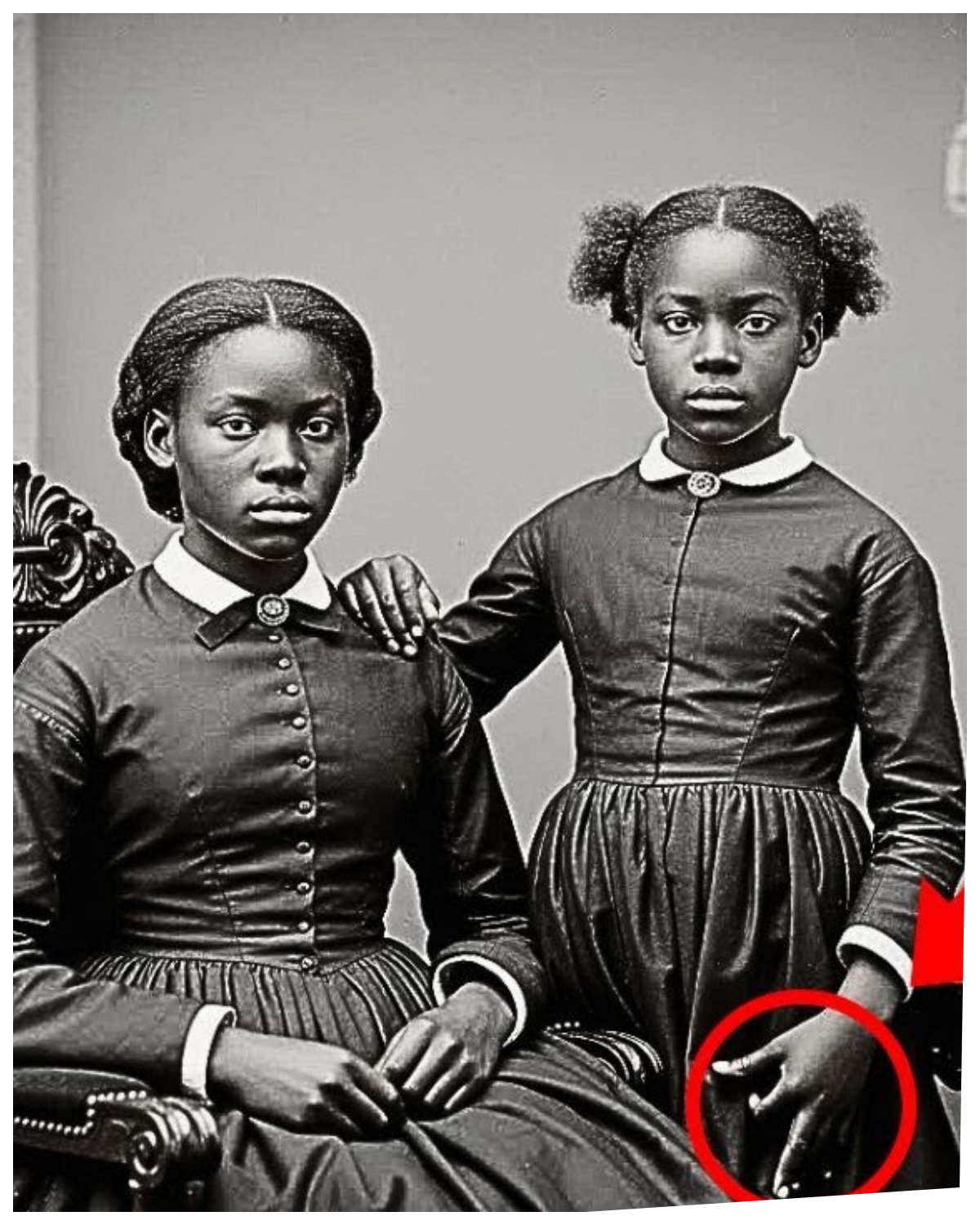

It was just a portrait of two sisters, and experts pale when they noticed the younger sister’s hand.

The photograph had been sitting in a cardboard box for over a century, wrapped in yellowed newspaper and forgotten in the basement of the Philadelphia Historical Society.

Dr.James Mitchell, a historian specializing in abolition movements, had spent the morning sifting through donated materials from an estate sale when his fingers brushed against the Dgeray’s smooth metal surface.

He pulled it out carefully, wiping decades of dust from the protective glass case.

What he saw made him pause.

Two young black girls stared back at him from 1863.

The older one, perhaps 16, sat rigidly in a carved wooden chair, her dark dress buttoned to the neck, her expression serious and composed.

The younger girl, no more than 12, stood beside her with one hand resting on her sister’s shoulder.

Their faces were striking.

Intelligent eyes, determined jaws, the kind of dignity that transcended the limitations of early photography.

James had examined thousands of Civil War era photographs.

Most followed the same stiff conventions of the time.

Subjects frozen in formal poses, hands clasped or resting on furniture, faces carefully neutral.

But something about this image felt different.

He turned on his desk lamp and held the dgerayotype closer to the light.

The studio backdrop showed typical Victorian elements, a painted garden scene, ornate curtains, a small table with artificial flowers.

The photographer had written on the back and faded ink, “Sisters, Philadelphia, October 1863.

” No names, no other details, just those three words and a date that placed the photograph in the middle of the bloodiest conflict in American history.

James set the image down and reached for his magnifying glass.

He’d learned long ago that photographs from this era often contained hidden stories, small details that revealed more than the subjects intended, or sometimes exactly what they intended.

His eyes moved systematically across the image, examining the girl’s clothing, the studio props, the way light fell across their faces.

Then he saw it.

The younger sister’s right hand, the one not resting on her sibling shoulder, hung at her side, but her fingers weren’t relaxed.

They were positioned deliberately, almost geometrically precise.

Her thumb and index finger formed a circle while her remaining three fingers extended upward at specific angles.

James felt his breath catch in his throat.

His hand trembled slightly as he adjusted the magnifying glass, bringing the girl’s hand into sharper focus.

He’d seen this gesture before, not in photographs, but in coded documents and secret correspondents from underground railroad operators.

It was a signal, a message hidden in plain sight.

James stood abruptly, his chair scraping against the wooden floor of his office.

He crossed to the filing cabinet where he kept his most sensitive research materials.

The documents too fragile or too valuable to store in the general archives.

His fingers moved quickly through folders until he found what he needed.

A leatherbound journal dated 1862 filled with sketches and notes compiled by William Still, the famous conductor and chronicler of the Underground Railroad.

He flipped through pages of coded messages, safe house locations, and communication methods used by abolitionists.

Threearters through the journal, he found the page he remembered.

William Still had documented various hand signals used by network members to identify themselves to strangers.

Signals that could be incorporated into everyday gestures or apparently formal photographs.

The drawing matched perfectly.

The circle formed by thumb and forefinger represented a safe house.

The three extended fingers indicated the number of rooms available for hiding.

The specific angle, fingers tilted slightly eastward, suggested the location within a city district.

James sat back down, his mind racing.

If this photograph was what he suspected, it wasn’t just a family portrait.

It was a message, a coded advertisement distributed among abolitionists to identify a new safe house in Philadelphia’s network.

The city had been a crucial hub for the Underground Railroad, its free black community providing shelter and support for thousands of escaped slaves heading north to Canada.

But why would someone encode such dangerous information in a photograph? The answer came to him immediately.

Plausible deniability.

If Confederate sympathizers or slave catchers discovered the image, it appeared innocuous, just two sisters posing for a portrait.

Only those who knew the code would understand its true meaning.

James picked up the dgeraype again, studying the older sister’s face with new appreciation.

She would have known what her younger sibling was doing.

The slight tension in her jaw, the way her eyes seemed to look directly through the camera.

She’d been nervous, aware of the risk they were taking.

He needed to find out who these girls were.

The photographers’s mark was still visible in the bottom corner.

Jay Taylor, photographer, 247 South Street, Philadelphia.

James grabbed his laptop and began searching historical records.

Many Civil War era photography studios had kept ledgers recording clients names and payment details.

If Taylor’s records had survived, they might be archived somewhere in the city.

2 hours later, he found a reference in the Library Company of Philadelphia’s digital catalog.

Jonathan Taylor’s business ledgers from 1860 to 1865 had been donated in 1923 and were available for research by appointment.

James immediately called the library’s special collections department.

I need to see the Taylor photography ledgers, he said when the archivist answered.

Specifically, October 1863.

It’s urgent.

The archivist, a woman named Patricia, hesitated.

We’re actually fully booked this week.

The earliest I could schedule you would be.

This is regarding Underground Railroad documentation, James interrupted.

Previously unknown material.

If I’m right, it could rewrite our understanding of how the network operated in Philadelphia.

There was a pause.

Then Patricia said, “Come tomorrow morning, 9:00.

I’ll have the ledgers waiting.

” The library company of Philadelphia smelled like old paper and furniture polish, a scent James had always found comforting.

Patricia, a woman in her 60s with silver hair and reading glasses hanging from a beaded chain, met him at the entrance to the special collections reading room.

She carried a slim leatherbound ledger with careful reverence.

October 1863, she said, placing it on the research table.

I have to admit, your call yesterday kept me up last night.

I’ve worked with these documents for years and never considered they might contain coded information.

James opened the ledger carefully.

Jonathan Taylor had kept meticulous records.

Each entry listed the date, client name, type of photograph, and price.

The handwriting was neat, methodical, the work of a careful businessman.

James ran his finger down the October entries, looking for anything that might correspond to two young sisters.

October 7th, Morrison family, four portraits, $12.

October 12th, wedding couple, eight dgeray types, $25.

October 18th, individual portrait, gentleman, $4.

Then he found it.

October 23rd, 1863.

Two sisters portrait paid in full schis dollars.

Client Ruth Freeman 412 Lombard Street.

James felt electricity run through him.

He pulled out his phone and opened a historical map of Philadelphia from the 1860s.

Lombard Street ran through the heart of the city’s black community, an area known for its abolitionist sympathies and underground railroad activity.

Can you look something up for me? He asked Patricia.

City directories from 1863.

I need to know who lived at 412 Lombard Street.

Patricia disappeared into the stacks and returned 10 minutes later with a thick directory.

She flipped to the L section, ran her finger down the page, and stopped.

Here, 412 Lombard Street.

Freeman household.

Listed as a boarding house operated by Ruth Freeman, Widow.

A boarding house, the perfect cover for underground railroad activity.

Escape slaves could hide among legitimate borders, their presence explained away as paying guests.

and Ruth Freeman.

The name suggested the older sister in the photograph.

Is there any way to find out more about this woman? James asked.

Census records, property deeds, anything.

Patricia smiled.

You’re in luck.

We have an extensive collection of African-American genealological records from this period.

Give me an hour.

James spent the time re-examining the photograph, noting every detail.

The girls dresses, while modest, were wellmade, not the clothing of the desperately poor.

The studio sitting would have cost money they’d chosen to spend despite other needs.

This photograph had been important to them.

Important enough to risk encoding a message that could have gotten them arrested or worse.

When Patricia returned, she carried a folder thick with photocopied documents.

Ruth Freeman, she began sitting across from James.

Born free in Philadelphia 1847.

Father was a ship carpenter, mother a seamstress.

Ruth and her younger sister Clara, that must be the girl in the photo, lost both parents to Kalera in 1861.

Ruth inherited the family property on Lombard Street at age 14.

14? James, looked up, startled.

She was running a boarding house at 14.

According to city records, yes, but here’s where it gets interesting.

Patricia pulled out another document.

I found references to the Freeman boarding house and correspondence from the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society.

Ruth’s name appears three times in coded messages between William Still and other conductors.

She was operating a safe house before she turned 16 years old.

James spread the documents across the table, creating a timeline of Ruth Freeman’s activities.

The picture that emerged was extraordinary.

After their parents died, Ruth and 12-year-old Clara had been left with a three-story house and debts they could barely manage.

Rather than sell the property, Ruth had transformed it into something remarkable, a boarding house that served as both legitimate business and covert underground railroad station.

The Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society letters provided fragments of the story.

In one dated March 1862, William Still wrote to a colleague, “The new station on Lombard operates with admirable discretion.

The proprie demonstrates exceptional capability.

” Another letter from July 1863 mentioned three packages safely delivered to the Freeman residence forwarded north within 48 hours.

Packages was common code for escaped slaves.

Forwarded north meant they had been moved to the next safe house on the route to Canada.

James pulled out his laptop and began cross referencing names and dates.

The Underground Railroad in Philadelphia had been a complex network with dozens of safe houses, conductors, and supporters working in careful coordination.

Most operators had been adults, ministers, businessmen, established members of the free black community.

Finding two teenage girls running a station was unprecedented in his research.

Patricia leaned forward, studying the photograph again.

Why would they risk putting a coded message in a permanent image? Wouldn’t that be dangerous? Actually, it was brilliant, James said.

Dgeray types were one of a kind images.

No negatives, no copies.

Unless you photographed the photograph itself, this would have been distributed only to trusted abolitionists.

And look at the date, October 1863.

That was right after the Battle of Gettysburg when Philadelphia was flooded with refugees and escaped slaves.

The network would have been desperate for new safe houses.

He pointed to Clara’s hand signal.

This photograph was their credential.

Any abolitionist who knew the code would understand immediately.

Here’s a new safe house, three rooms available, located in the Eastern District.

Ruth probably carried copies to Underground Railroad meetings, showed them to conductors, used them to establish trust without having to explain verbally what they were doing.

Patricia sat back clearly moved.

Two young girls orphaned turning their grief into resistance.

That’s a powerful story.

If we can prove it, James cautioned.

Right now, we have circumstantial evidence.

The hand signal, Ruth’s name, and Anti-Slavery Society correspondents, the timing of the photograph.

We need more.

We need to find out what happened to these sisters, whether anyone documented their activities in more detail.

He spent the next 3 hours combing through archives.

Philadelphia’s abolitionist community had been meticulous about keeping records, understanding that their work was historically important.

But most of those records focused on prominent figures.

William Still, Robert Pervvis, Lricamat, the everyday operators, especially young people and women, often went unmentioned.

Then James found something unexpected.

In a collection of personal letters donated by a descendant of Robert Pervvis, there was a note dated November 1863, just weeks after the Freeman photograph was taken.

Pervvis wrote to William Still, “Please provide additional support to the Lombarded Street station.

The young women there show remarkable courage, but require guidance and resources.

Their youth makes them vulnerable to scrutiny.

” Vulnerable to scrutiny.

James understood immediately what that meant.

Slave catchers and Confederate sympathizers were always watching, always looking for evidence of underground railroad activity.

Two teenage girls running a boarding house would have attracted attention, raised questions.

The community had been trying to protect them.

James knew he needed to expand his search beyond traditional archives.

The Freeman sister’s story, if he was right about it, would have left traces in unexpected places.

Property records, church registries, newspaper advertisements.

He started with the Philadelphia city directories, tracking the Lombard Street address through consecutive years.

1863 Freeman boarding house are Freeman proprietors.

1864 same listing.

1865 same listing.

Then in 1866, the entry changed.

412 Lombard Street, private residence, R.

Freeman.

The boarding house had closed.

The timing was significant.

The Civil War ended in April 1865.

With slavery abolished and the Underground Railroad no longer necessary, many safe houses had ceased operations.

But why would Ruth close a legitimate business that provided her income? James pulled out his phone and called a colleague at Temple University, Dr.

Lisa Washington, who specialized in post civil war African-American history in Philadelphia.

She answered on the second ring.

I need your expertise, James said, explaining what he’d found.

Two sisters, Ruth and Clara Freeman, ran what I believe was an underground railroad safe house disguised as a boarding house.

The business closed in 1866.

I need to know what happened to them after the war.

Lisa was quiet for a moment.

Freeman.

Freeman.

That name is familiar.

Give me a few hours.

I might have something.

While he waited, James returned to the photograph.

He noticed something he’d missed before.

A small pin on Ruth’s dress collar, barely visible in the Dgeray’s aged surface.

He borrowed Patricia’s high-powered magnifying equipment, and examined it closely.

The pin appeared to be circular with what looked like a raised hand in the center, the symbol of the Anti-Slavery Society.

These pins had been distributed to active members and supporters worn as quiet declarations of allegiance.

For Ruth to wear it in a photograph meant she wasn’t hiding her beliefs despite the danger.

His phone rang.

Lisa’s voice was excited.

I found her.

Ruth Freeman.

She’s in the records of the Institute for Colored Youth.

That’s what became Cheney University.

She enrolled in 1866 as a teacher training student.

A teacher? James said surprised.

There’s more.

I found a commencement program from 1868.

Ruth Freeman graduated top of her class and gave a speech at the ceremony.

Someone transcribed it for the Christian Recorder newspaper.

I’m looking at it right now.

Lisa paused and James could hear papers rustling.

She talked about education as the continuation of liberation.

She said, “We who helped our brothers and sisters find freedom in the north must now help them find freedom in knowledge and self-sufficiency.

” We who helped.

It wasn’t quite a confession, but it was close.

Ruth had been speaking to an audience who understood exactly what she meant.

What about Clara? James asked.

The younger sister.

That’s where it gets complicated, Lisa said.

I can’t find any records of Clara Freeman after 1865.

No census listings, no school records, nothing.

It’s like she disappeared.

James felt a chill.

In Underground Railroad history, disappearances were rarely good signs.

Conductors and safe house operators had been arrested, attacked, sometimes killed by slave catchers or Confederate sympathizers.

Had something happened to Clara? There’s one more thing, Lisa added.

I found a brief mention in an 1867 Philadelphia Tribune article about Ruth Freeman’s enrollment at the institute.

It says she dedicated her studies to the memory of her beloved sister.

That suggests Clara died probably sometime between 1863 and 1867.

James needed to find out what happened to Clara Freeman.

The gap in the historical record bothered him, a 12-year-old girl who appeared in a photograph in 1863 and then vanished from documentation entirely.

He returned to the library company and asked Patricia if they had any death records from the period.

Philadelphia’s burial records are scattered, Patricia explained.

Some are with individual churches, some with a city, but there’s a collection of African-American burial records from several cemeteries compiled by a genealogologist in the 1980s.

Let me check.

She returned with a microfilm reader and several rolls of film.

Together they scrolled through hundreds of names looking for Clara Freeman.

It took almost two hours before they found her.

Clara Freeman died.

February 14th, 1864, age 13.

Buried at Lebanon Cemetery.

Cause of death, pneumonia.

James sat back, the weight of that simple entry settling over him.

Clara had died just 4 months after the photograph was taken in the middle of one of Philadelphia’s coldest winters.

Pneumonia was common in the 1860s, especially in crowded urban areas with poor heating and ventilation.

But James knew that underground railroad safe houses were particularly vulnerable to disease.

Strangers constantly passing through, people arriving sick or malnourished from their journeys, cramped conditions that made illness spread quickly.

Had Clara contracted pneumonia from one of the refugees she was helping? It was impossible to know for certain, but the timing suggested it.

The winter of 1863 to 1864 had been brutal, and the Freeman boarding house would have been filled with people seeking shelter.

James thought about the photograph again, seeing it now with new understanding.

That image had been taken in October 1863, perhaps just months before Clara fell ill.

The hand signal she’d made so carefully, the code she’d learned to help escaped slaves find safety.

She’d been captured making that gesture, frozen in time, not knowing she had only a few months left to live.

He called Lisa again.

I found Clara.

She died in February 1864, age 13.

Pneumonia.

Lisa was quiet for a moment.

That explains why Ruth closed the boarding house and went to school.

She’d lost everyone, parents, sister, all by the time she was 17.

Teaching must have been her way of moving forward.

I need to find out if anyone documented the Freeman sisters underground railroad work more explicitly, James said.

Personal diaries, letters, anything that confirms what we suspect.

There’s one place you haven’t checked, Lisa said.

The Mother Bethl AM Church archives.

It’s the oldest African Methodist Episcopal Church in the country, and it was deeply involved in Underground Railroad activities.

If the Freeman sisters were connected to the abolitionist network, they would have had ties to that church.

The next morning, James drove to Mother Bethl AM Church on 6th Street.

The building itself was a reconstruction.

The original church had been demolished in the 1890s, but the congregation had maintained meticulous records dating back to its founding in 1794.

The church archivist, a retired minister named Reverend Thomas Carter, met him in a small office filled with document boxes and ledgers.

The Freeman family, Reverend Carter said, pulling out a membership ledger.

Yes, I know these names.

Ruth and Clara’s parents were active members.

The father, Samuel Freeman, served as a trustee before his death.

He flipped through pages.

After Samuel and his wife died, Ruth continued attending services.

She was listed as a financial contributor, which was unusual for someone so young and presumably struggling financially.

Reverend Carter set a worn leather journal on the table between them.

This, he said, belonged to Reverend Daniel Payne, who served as pastor here during the Civil War years.

He kept detailed notes about the congregation’s activities, including their work with the Underground Railroad.

It’s never been fully transcribed or published, too sensitive historically, and the handwriting is difficult to read.

James opened the journal carefully.

The pages were filled with dense, cursive writing, entries dated and organized chronologically.

He began scanning through 1863 looking for any mention of the Freeman name.

He found it on a page dated November 1863, just weeks after the photograph had been taken.

Reverend Payne wrote, “Visited the Freeman residence on Lombard Street today.

Young Ruth shows maturity beyond her years, managing both the business and the sacred work with equal dedication.

Her sister Clara, though young, demonstrates remarkable discretion and courage.

I impressed upon them the importance of caution.

Their youth makes them vulnerable to suspicion and enemies of our cause.

watched these streets constantly.

James felt his pulse quicken.

This was direct confirmation.

A contemporary witness, a respected minister, explicitly acknowledging the Freeman Sisters Underground Railroad activities.

He continued reading.

A later entry from December 1863.

The Lumber Street Station reports increased traffic.

Four souls sheltered last week alone, all successfully forwarded to the next conductor.

The younger Freeman girl has proven particularly valuable.

Her age allows her to move through the streets without attracting attention, delivering messages and supplies that would draw scrutiny if carried by adults.

So Clara hadn’t just been helping inside the house.

She’d been an active courier, carrying coded messages between safe houses, her youth serving as camouflage.

It was dangerous work, work that would have put her in constant contact with cold weather, dangerous neighborhoods, and potential exposure to illness.

The final mention came in February 1864.

Heavy heart today.

Young Clara Freeman succumbed to pneumonia after three weeks of illness.

The congregation mourns her loss.

She died in service to the cause of freedom as surely as any soldier.

Her sister Ruth is devastated but resolute.

I fear what this loss will do to one so young who has already endured so much.

James sat back, emotion tightening his throat.

Here was the complete picture.

Two orphaned sisters, barely teenagers, turning their home into a refuge for escaped slaves.

Clara at 12 and 13 serving as a messenger and courier moving through Philadelphia’s winter streets carrying dangerous secrets then falling ill and dying her short life spent in resistance and service.

Reverend Carter watched him quietly.

You found something significant.

These girls, James said, they were operating a major safe house and Clara was working as an active courier all while they were children essentially.

I’ve never seen documentation of underground railroad operators this young.

The history we’ve recorded has always focused on adults, Reverend Carter said.

Ministers, businessmen, established community members.

But the truth is that entire families participated.

Children, teenagers, elderly people, everyone who could contribute did.

The Freeman sisters weren’t unique in their youth, just uniquely documented.

James photographed the relevant pages of Reverend Payne’s journal, ensuring he captured every word about the Freeman Sisters.

Is there anything else in your archives about them? Letters, church records, anything? Reverend Carter thought for a moment.

There might be something in the benevolent society records.

The church operated a mutual aid society that supported members in need.

After Clara died, Ruth would have received assistance.

Let me look.

He disappeared into an adjacent storage room and returned with a wooden box filled with financial ledgers and correspondence.

This is from the Women’s Benevolence Society, 1860, 1870.

They kept records of every family they assisted and why.

The Women’s Benevolence Society records painted a picture of community care that James found deeply moving.

After Clara’s death in February 1864, the society had immediately rallied around 17-year-old Ruth, providing both financial support and emotional comfort.

The entries were written in a clear feminine hand, probably by the society’s secretary.

February 18th, 1864.

Emergency meeting held for Ruth Freeman following the death of her sister Clara.

unanimous vote to provide $15 for funeral expenses and $10 monthly support for three months.

Sister Freeman has lost her entire family and continues the dangerous work of sheltering fugitives despite her grief.

She requires our active protection and assistance.

On March 1864, visited Ruth Freeman at Lombard Street residence.

She maintains her composure, but the strain is evident.

Currently sheltering two families, seven persons total.

We provided additional blankets, food supplies, and $5 for coal.

Sister Freeman refuses to close her doors despite her personal loss, stating, “Clara died helping others find freedom.

I cannot stop now.

” James felt the historical weight of those words.

Ruth, at 17, alone and grieving, had chosen to continue the work that had cost her sister’s life.

It was an act of extraordinary courage and conviction.

The entries continued through 1864 and into 1865.

The benevolent society visited monthly, sometimes more often, providing supplies and financial support.

They also, James noticed, provided something else, witnesses.

By documenting their visits, the church women were creating evidence that Ruth’s boarding house was legitimate, that she had community support, that she was a respectable young woman deserving of protection.

April 1865, entry.

Great rejoicing.

The war has ended.

Sister Freeman’s boarding house now shelters freed men arriving from the south seeking work and housing.

The dangerous work is finished, but the necessary work continues.

Then came the transition year, 1866, when Ruth closed the boarding house and enrolled in teacher training.

An entry from September 1866 explained, “Sister Ruth Freeman has chosen to pursue education, seeking to become a teacher.

We support this decision wholeheartedly.

She has given three years of her young life to the cause of freedom, sacrificing her childhood and losing her beloved sister in the process.

Now she must be allowed to build her own future.

We have established a scholarship fund to support her studies.

James sat back, overwhelmed by the depth of community care these records revealed.

The Freeman sisters hadn’t been operating alone.

They’d been supported by an entire network of church members, benevolent society women, fellow abolitionists, all working together to protect these young girls as they did extraordinarily dangerous work.

Reverend Carter smiled at James expression.

The Underground Railroad wasn’t just about conductors and safe houses.

It was about entire communities making the choice to resist injustice together.

The Freeman sisters were brave, certainly, but they were also held and protected by people who understood what they were risking.

I need to find out what happened to Ruth after she became a teacher.

James said, “The story can’t end in 1866.

I can help with that,” Reverend Carter said.

He pulled out another ledger, this one more recent.

“Our church has maintained member records continuously.

Ruth Freeman married in 1872 to a man named Thomas Williams, a school teacher.

She continued teaching until 1890.

They had four children, all of whom she educated herself before they attended formal school.

He flipped forward several pages.

Ruth Williams, formerly Freeman, died in 1919, age 72.

Her obituary in the Philadelphia Tribune described her as a pioneering educator and devoted member of Mother Bethl Ame Church.

It made no mention of her underground railroad activities.

“Why not?” James asked, surprised.

By 1919, many people involved in the Underground Railroad had chosen to keep those stories private.

Reverend Carter explained, “The work had been illegal after all.

Some feared legal complications for their families.

Others simply felt the work spoke for itself and didn’t need public recognition.

Ruth apparently chose silence.

” James knew the story was incomplete without one crucial element.

Ruth’s descendants.

If she’d had four children, there would be grandchildren, great-grandchildren, perhaps even great great grandchildren alive today who had no idea their ancestor had been an underground railroad conductor at age 14.

He contacted Dr.

Lisa Washington again, and together they began searching genealological records.

The trail of Ruth Freeman Williams descendants led them through four generations.

Her children born between 1873 and 1884, their children born in the early 1900s, those children’s children through the mid-century, and finally the current generation.

One name stood out.

Jennifer Williams, age 42, a high school history teacher living in West Philadelphia.

According to their research, Jennifer was Ruth’s great great granddaughter.

James found her email through the school district website and sent a carefully worded message explaining his research and asking if she’d be willing to talk.

She responded within 2 hours.

I’m stunned.

My great great grandmother, Ruth, an Underground Railroad conductor at 14.

Please call me immediately.

When James called, Jennifer’s voice was breathless with excitement and emotion.

I knew almost nothing about Ruth, she said.

My grandmother mentioned her once, said she’d been a teacher in the 1800s, but that was all.

We have one photograph of her from the 1890s.

She’s elderly, standing with her children.

I never imagined 14 years old, operating a safe house.

There’s another photograph, James said gently.

From 1863, Ruth and her sister Clara.

It’s actually how I discovered this entire story.

He explained about the hand signal, the coded message, everything he’d uncovered.

Jennifer was quiet for a long moment.

When she spoke again, her voice was thick with tears.

Clara died at 13.

Pneumonia, likely contracted while doing underground railroad work.

She was serving as a courier, carrying messages between safe houses.

Can I see the photograph? James sent her a high resolution scan.

10 minutes later, his phone rang again.

Jennifer was crying openly now.

They’re so young.

They’re children.

Ruth looks so serious, so determined.

And Clara, she paused.

Clara’s making the hand signal, the code.

God, she’s just a little girl, and she’s standing there making this secret signal that could have gotten them both killed.

Your great great grandmother was extraordinary, James said.

Both sisters were.

I’m writing a paper about this, but I wanted your permission first.

This is your family’s history.

Permission? Jennifer said, Dr.

Mitchell, this story needs to be told.

Black children, orphans turning their trauma into resistance, turning their home into a refuge for people fleeing slavery.

How many people know that teenagers, that children were operating safe houses? This changes everything we think we know about who participated in the Underground Railroad.

They talked for over an hour.

Jennifer shared what little family history had been passed down.

Ruth’s devotion to education, her insistence that all her children and grandchildren learn to read and write before age five, her quiet strength and fierce protectiveness of family.

None of the family stories had included her underground railroad work.

“Why do you think Ruth never told anyone?” Jennifer asked.

James considered the question.

By the time she was old enough to feel safe sharing those stories, decades had passed.

Maybe the pain of losing Clara was too great.

Maybe she felt the work was simply her duty and didn’t require recognition.

Or maybe she believed the most important legacy wasn’t the story of what she’d done, but the values she’d instilled in her children.

Courage, service, education as a form of liberation.

I teach history, Jennifer said quietly.

African-American history specifically.

And I had no idea my own great great-grandmother was part of this.

What else are we missing? How many other stories are lost? 3 months later, James stood in the auditorium of the Philadelphia Historical Society preparing to present his findings.

The room was packed.

Historians, genealogologists, community members, journalists.

Jennifer Williams sat in the front row with her teenage daughter Ruth’s great great great granddaughter.

On the screen behind James was the photograph.

Two young sisters, Ruth and Clara Freeman, captured in October 1863.

Clara’s right hand hung at her side, fingers positioned in that careful, deliberate signal.

Three rooms available.

Safe house, Eastern District.

This photograph, James began, has been in our archives for over a century.

We cataloged it as two sisters, Philadelphia, 1863.

Nothing more.

But photographs from this era are rarely just images.

There are documents, messages, sometimes even acts of resistance frozen in time.

He walked the audience through his research.

The hand signal, William Still’s journal, Jonathan Taylor’s ledger, Reverend Payne’s notes, the benevolent society records.

Each piece of evidence built on the last, creating an undeniable picture of two orphaned teenagers operating an underground railroad safe house in the heart of Philadelphia.

Ruth Freeman was 14 years old when she inherited her family home and chose to transform it into a refuge for escaped slaves.

James said her sister Clara was 12.

For over a year, they sheltered dozens of people fleeing bondage, coordinated with other conductors, maintained their cover as a legitimate boarding house, all while knowing they could be arrested, attacked, or killed at any moment.

He clicked to the next slide.

Clara’s death record.

Clara Freeman died in February 1864, age 13.

The cause was pneumonia, likely contracted during her work as a courier for the Underground Railroad Network.

She spent the last months of her life carrying secret messages through Philadelphia’s winter streets, helping coordinate the movement of escaped slaves through the city.

The auditorium was completely silent.

James could see tears on Jennifer’s face, and many others in the audience were visibly moved.

Ruth continued the work alone after Clara’s death, he continued.

At 17, grieving and isolated, she chose not to close her doors.

She kept the boarding house operating until the war ended in 1865.

Then she closed it, enrolled in teacher training, and spent the next 25 years educating freed people and their children.

She married, had four children of her own, and died in 1919 at age 72.

Her obituary made no mention of her underground railroad activities.

James paused, letting that sink in.

Ruth chose silence.

We’ll never know exactly why, but what we do know is that her legacy continued through her descendants, teachers, activists, community leaders who carried forward her values of education, service, and quiet courage, even without knowing the full story of where those values came from.

He gestured to Jennifer.

Ruth Freeman’s great great granddaughter is here today.

Jennifer Williams is herself a history teacher, continuing her ancestors commitment to education and truthtelling.

She gave me permission to share this story publicly, and I’m grateful to her and her family for trusting me with it.

Jennifer stood, wiping her eyes.

When Dr.

Mitchell first contacted me, I was shocked.

Then I was angry.

Angry that this story had been lost, that my grandmother died without knowing her great-grandmother had been a hero.

But now I understand something.

Ruth’s legacy wasn’t in public recognition or historical fame.

It was in the values she taught her children and grandchildren.

Courage in the face of injustice, service to community, the belief that even one person, even a child, can make a difference.

Those values didn’t need explanation.

They were simply who we were raised to be.

James returned to the podium.

This photograph represents thousands of untold stories.

The Underground Railroad wasn’t just operated by famous conductors and established adults.

It was sustained by entire communities, including children and teenagers who risked everything to help others find freedom.

How many other photographs sit in archives, coded messages waiting to be deciphered? How many young people participated in this resistance movement and then disappeared from history? He looked at the image one final time.

Ruth and Clara Freeman were children when they made the choice to turn their home into a battlefield in the war against slavery.

Clara paid for that choice with her life.

Ruth carried the weight of that loss for 72 years.

They deserve to be remembered, not as footnotes or curiosities, but as the courageous young women they were.

The presentation ended to sustained applause.

Afterward, dozens of people approached James with questions, leads on similar stories, family histories that might contain hidden underground railroad connections.

One elderly woman showed him a dgeray type of her great-grandfather, asking if James noticed anything unusual about how his hands were positioned.

Jennifer stood beside the projected photograph, her daughter next to her, both studying the faces of Ruth and Clara.

They look like us, the teenager said softly.

Around the eyes, we have the same eyes.

You have the same courage, too, Jennifer told her daughter.

That’s the real inheritance.

Not a photograph or a story, but the knowledge that when your ancestors faced impossible choices, they chose to help others.

They chose resistance.

They chose hope.

James watched them, thinking about legacy and memory, about stories lost and recovered.

This photograph would now take its place in history textbooks, in museums, in academic studies of the Underground Railroad.

But its most important legacy would be personal.

A family reconnected with their ancestors extraordinary courage.

a teenager learning that resistance runs in her blood.

As the audience dispersed, James carefully packed the dgeraype back into its protective case.

The photograph was no longer just an artifact.

It was testimony, evidence that ordinary people, even children, could change history through acts of courage performed in the shadows.

Coded messages hidden in plain sight.

Small hands forming signals that meant, “Here is safety.

Here is refuge.

Here is freedom.

” Clara Freeman’s hand would forever be frozen in that gesture.

A 12-year-old girl’s silent declaration that she stood on the side of justice no matter the

News

🔥 Vatican Meltdown as “Pope Leo XIV” Allegedly Unseals a Forbidden Scroll Said to Rewrite Christ’s Final Words and Expose Centuries of Holy Silence — In a voice dripping with irony and suspense, insiders whisper that a newly crowned pontiff stared down trembling cardinals and hinted at a dust-choked parchment hidden since the crucifixion itself, a so-called final commandment rumored to demand compassion over power, shaking faith, egos, and vault doors while skeptics snarl and believers gasp, because nothing rattles Rome like the suggestion that heaven’s last memo was buried on purpose and now the walls are listening 👇

The Revelation of Pope Leo XIV: A Shocking Unveiling In the heart of the Vatican, a storm brewed beneath the…

This 1889 studio portrait looks elegant — until you notice what’s on the woman’s wrist

This 1889 studio portrait appears elegant until you notice what’s wrapped around the woman’s wrist. Dr.Sarah Bennett had spent 17…

At first, it looked like a photo of two sisters—but then historians noticed their hands

At first, it looked like a photo of two sisters, but then historians noticed their hands. The archive room of…

It was just a portrait of a soldier and his wife—until you notice what he’s holding

It was just a portrait of a soldier and his wife until you notice what he’s holding. The photograph arrived…

It was just a portrait of a mother — but her brooch hides a dark secret

It was just a portrait of a mother and her family, but look more closely at her brooch. The estate…

It was just a seemingly innocent wedding photo from 1920 — but pay attention to the groom’s hand

It was just a seemingly innocent wedding photo from 1920. But pay attention to the groom’s hand. The Maxwell estate…

End of content

No more pages to load