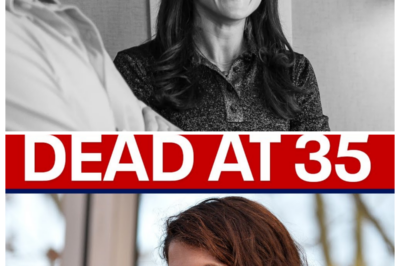

It Was Just a Portrait of a Young Couple in 1895 — But Look Closely at Her Hand

It was just a portrait of a young couple in 1895.

But look closely at her hand.

The afternoon sunlight filtered through the tall windows of the Charleston Historical Society, casting long shadows across Dr.

Maya Richardson’s desk.

She had been cataloging donated photographs for 3 hours, her eyes growing tired from examining faded sepia tones and cracked emulsions.

Most were unremarkable.

Stiffposed families, stoic children, elderly couples staring solemnly at the camera as if challenging eternity itself.

Then she pulled out photograph number 47.

It showed a young black couple, probably in their mid20s, standing in front of a painted backdrop depicting a Victorian parlor.

The man wore a dark suit that seemed slightly too large, his posture rigid and formal.

The woman beside him wore a high-necked dress with intricate lace detailing, her hair swept up in the fashion of the 1890s.

On the back, in faded pencil, someone had written, “Thomas and Sarah, Charleston, South Carolina, April 1895.

” Maya almost moved on to the next photograph.

Almost.

But something made her pause.

She picked up her magnifying glass and leaned closer, studying the woman’s face.

Sarah’s expression was carefully neutral, her eyes fixed on the camera lens with an intensity that seemed to burn through the decades.

There was no smile, no warmth, just an unsettling vacancy that didn’t match the formal occasion of having one’s portrait taken.

An expensive and rare event for a black couple in the post reconstruction south.

Mia’s gaze drifted downward, following the elegant lines of Sarah’s dress to where her hands rested at her sides.

The right hand hung naturally, relaxed.

But the left hand, Maya’s breath caught.

The left hand was positioned oddly, fingers spread in a specific configuration that didn’t look accidental.

The thumb and index finger formed a small circle, while the other three fingers extended upward, slightly separated.

It was subtle, barely noticeable unless you were looking for it, hidden in the folds of her dark dress.

Maya set down the magnifying glass, her heart beating faster.

She had seen that gesture before in her research on underground railroad signals and coded communications used by enslaved people.

But this photograph was dated 1895, 30 years after the Civil War ended, decades after emancipation.

Why would a free black woman in 1895 be making a distress signal in a formal portrait? Maya pulled out her phone and photographed the image, zooming in on Sarah’s hand.

The gesture was unmistakable once you saw it.

This wasn’t a random positioning or a trick of the camera.

This was deliberate.

This was intentional.

This was a cry for help, frozen in time for 129 years, waiting for someone to notice.

Maya couldn’t stop thinking about the photograph.

That evening, in her small apartment overlooking the Charleston Harbor, she spread copies of the image across her dining table alongside her laptop and research notebooks.

The ceiling fan turned slowly overhead, barely moving the humid April air that pressed against the windows like something alive.

She started with the basics.

Thomas and Sarah, Charleston, 1895.

No surnames, which was frustratingly common for black families in that era.

Official records were often incomplete or deliberately obscured.

names misspelled or omitted entirely by white clerks who saw black lives as barely worth documenting.

Maya opened the 1900 federal census database and began searching Charleston County.

The census had been taken just 5 years after the photograph.

If Thomas and Sarah were still in Charleston, still together, they should appear somewhere in those records.

Hours passed.

The harbor lights glittered in the darkness beyond her window.

Maya’s coffee grew cold, forgotten.

Finally, at nearly midnight, she found something.

a Thomas and Sarah living on Street in Charleston’s upper peninsula.

Thomas was listed as a carpenter, aged 29.

Sarah, a 26, had no occupation listed, which meant she was likely working domestic jobs that census takers didn’t bother to record.

They had been married for 7 years, which would place their wedding around 1893, 2 years before the photograph.

Maya sat back processing this information.

Newlyweds, essentially, a young couple building a life together in one of the most dangerous periods for black Americans in the South.

The 1890s saw the rise of Jim Crow laws, the systematic disenfranchisement of black voters, and an epidemic of lynchings that terrorized black communities across the region.

She pulled up statistics she had memorized during her doctoral research.

In 1895 alone, over 100 black Americans were lynched in the United States.

South Carolina had been particularly violent with white mobs targeting black men for alleged crimes, or for no reason at all except to maintain terror and control.

Maya looked again at the photograph, at Thomas’s stiff posture and oversized suit.

At Sarah’s carefully blank expression in that subtle, desperate hand signal.

What had happened to them? She searched death records next, her stomach tight with dread.

The Charleston County records from that era were incomplete, especially for black residents.

But she had to try.

Nothing for Thomas in 1895.

Nothing in 1896.

She kept searching year by year and found him in the 1910 census, still working as a carpenter, now aged 39.

But Sarah wasn’t listed beside him.

Maya’s hands trembled slightly as she typed Sarah’s name into the death records database, narrowing the search to 1895 1900.

The screen loaded slowly and there it was.

Sarah, wife of Thomas, died August 1895, age 26.

Cause of death.

Complications from injuries sustained in fall 4 months after the photograph was taken.

Maya arrived at the Charleston Historical Society at dawn, unable to sleep after finding Sarah’s death record.

The building was still locked, so she sat on the front steps with her laptop, watching the city wake up around her.

Delivery trucks rattling down narrow streets, early commuters heading toward the harbor, tourists already gathering near the historic market.

When the security guard finally unlocked the doors at 8:00, Maya was the first one through.

She went straight to the archives, pulling the donation file for the photograph collection.

Every donation came with paperwork, who donated it, when, and any accompanying information about the items.

The photograph of Thomas and Sarah had been part of a larger collection donated three months ago by an estate sale company clearing out a house on Trad Street.

Mia called the company.

A tired sounding woman answered on the fifth ring.

I’m trying to track down information about a photograph collection you donated to the historical society.

Maya explained.

It came from a house on Trad Street.

Oh, the Morrison estate, the woman said.

Sad situation.

The owner died without any heirs.

House had been in the family since before the Civil War.

We found boxes and boxes of old photographs in the attic.

Nobody wanted them, so we donated the lot.

Do you remember anything else in those boxes? Any papers, letters, documents? Honey, there were probably 20 boxes.

We didn’t go through everything.

Most of it went to the dump, honestly.

Historical society only took the photographs.

Maya’s heart sank.

Is the house still there? Has it been cleaned out completely? Should be.

New owner takes possession next week, but if you want to look around, you’d better hurry.

2 hours later, Maya stood in front of a narrow three-story house on Trad Street.

Paint peeling from the shutters, weeds growing through cracks in the brick sidewalk.

The estate company had given her permission to search what remained before the new owner arrived.

Inside, the house smelled of mildew and age.

Dusty furniture sat covered in sheets.

Maya’s footsteps echoed on the hardwood floors as she climbed stairs to the attic.

The space was sweltering, airless, filled with the detritus of generations.

Old furniture, trunks, boxes of clothes eaten by moths.

Maya began searching systematically, opening every container, checking every corner.

In the far corner, behind a broken rocking chair, she found a wooden crate marked photographs, various.

Inside were loose papers, letters, receipts, the ephemera the estate company hadn’t bothered to sort.

Maya knelt on the dusty floor and began reading.

Most were mundane.

Bills from merchants, receipts for household goods, letters about social engagements.

Then, near the bottom of the crate, she found an envelope addressed to Mrs.

Elizabeth Morrison, Tad Street, Charleston.

The postmark read, September 1895.

Inside was a single sheet of paper written in careful formal handwriting.

Dear Mrs.

Morrison, I’m writing to inform you of a matter most distressing regarding your former housemmaid Sarah.

As you know, she departed your service in April of this year following her marriage.

It has come to my attention that she suffered a tragic accident in August and has since passed.

Her husband Thomas has asked if you might have any information about Sarah’s family as he wishes to notify them of her death but has no knowledge of her origins.

If you can provide any assistance in this matter, Thomas may be reached through Reverend Patterson at Emanuel Church.

Most respectfully, Mrs.

Katherine Simmons.

Maya read it three times, her mind racing.

Sarah had been a housemmaid in this very house.

The Morrison family had employed her until she married Thomas in early 1895, and then just 4 months later, she was dead.

Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church stood on Calhoun Street, its white steeple rising above the surrounding buildings like a beacon.

Maya had passed it countless times, knowing its deep significance in Charleston’s black history, founded in 1817, burned by white authorities for suspected involvement in an 1822 slave rebellion planned by Denmark Vizy, rebuilt, closed during the Civil War, reopened after emancipation.

This church had witnessed everything.

Reverend Marcus Johnson met her at the entrance.

A tall man in his 60s with silver hair and kind eyes behind wire- rimmed glasses.

Maya had called ahead, explaining her research.

Our records from the 1890s are fragmented,” he warned as he led her down to the church basement where old ledgers and documents were stored in climate controlled cabinets.

“The church was burned again in 1886 during the earthquake fires.

” “Well, we lost a lot, and recordkeeping wasn’t always systematic, especially for members who couldn’t read or write.

” “I understand,” Maya said.

“I’m looking for anything about a couple named Thomas and Sarah, married around 1893, and a Reverend Patterson who would have been here in 1895.

” Reverend Johnson pulled out several leatherbound ledgers.

Their pages yellowed and brittle.

Patterson.

Yes.

Reverend William Patterson served here from 1890 to 1897.

He kept meticulous records.

Actually, let’s see.

They sat at a long table under fluorescent lights, carefully turning pages, marriage records, baptisms, deaths, lists of congregants, the names of people who had lived and loved and died reduced to lines of fading ink.

Then my saw Thomas Daniels and Sarah married April 7th, 1893.

Sarah with no surname.

Reverend Johnson noted that usually meant she had been enslaved or her parents had been.

Sometimes people didn’t know their family names or chose not to use the surnames of former enslavers.

Is there anything else about them? Any other records? Reverend Johnson turned more pages than paused here.

August 28th, 1895.

Funeral service for Sarah Daniels, wife of Thomas, buried at Magnolia Cemetery, colored section.

He looked up at Maya.

Reverend Patterson added a note here in the margin.

See? Maya leaned closer in small cramped handwriting someone had written inquiry from T.

Daniels regarding marks on deceased.

No answers provided.

Matter closed.

Marks on deceased? Maya whispered.

What does that mean? Reverend Johnson’s expression grew somber.

In that era when black people died under suspicious circumstances, which was often, families would sometimes ask for investigations, but white authorities rarely cared.

Domestic accidents, falls, sudden deaths, they were all convenient ways to avoid questions about violence.

Maya felt a chill despite the warm basement air.

“You think Sarah’s death wasn’t an accident?” “I think,” Reverend Johnson said carefully.

“That we may never know the truth.

” But Reverend Patterson clearly thought Thomas’s concerns were legitimate enough to record them.

“That tells me something wasn’t right.

” Ma pulled out her phone and showed him the photograph of Thomas and Sarah, zooming in on Sarah’s hand gesture.

“I found this in a donated collection.

Does this hand signal mean anything to you?” Reverend Johnson studied it for a long moment, his face growing increasingly troubled.

I’ve seen variations of this in historical accounts.

During slavery, it was one of several signals used by people seeking help from the Underground Railroad.

But by 1895, he trailed off thinking there were still situations where black people needed secret ways to communicate distress.

Domestic servitude could be dangerous, especially for young women working in white households.

Some employers took liberties, and a black woman had no legal recourse, no protection.

Sarah was a housemmaid, Maya said.

She worked for the Morrison family on Trad Street until she married Thomas.

Reverend Johnson met her eyes, and four months after marrying, she’s dead.

With marks on her body that made her husband question the official story.

I need to find out what really happened to her.

The Charleston County Library’s genealogy section occupied the entire third floor, a quiet space filled with microfilm readers, filing cabinets, and researchers bent over old documents.

Maya had become a regular fixture there over the past week, arriving when the library opened and staying until closing.

She was building a picture of the Morrison family piece by piece.

James Morrison had been a prosperous cotton merchant before the Civil War.

His wealth built on the labor of enslaved people.

After the war, the family fortune had diminished, but not disappeared.

They still owned the Trad Street house, still employed servants, still moved in Charleston’s white social circles.

In 1895, the household consisted of James Morrison, his wife Elizabeth, and their adult son, Robert, who was 28 years old, 2 years older than Sarah would have been.

Maya found Robert Morrison’s name in newspaper archives, society pages, mostly engagement announcements, charity events, descriptions of parties at the Morrison House.

The entries painted a picture of a young man of privilege, educated, expected to take over his father’s business interests.

Then she found something else.

A brief mention in the Charleston News and Courier from July 1895, one month before Sarah’s death, Robert Morrison, son of Mr.

and Mrs.

James Morrison of Tradere, departed Saturday last for an extended tour of Europe.

He’s expected to remain abroad for the remainder of the year.

Maya sat back, her mind working.

Why would a young man suddenly leave for Europe in the middle of summer? Charleston’s elite typically traveled in winter, escaping to cooler climates.

Summer departures were unusual.

She searched for more information about Robert Morrison’s European trip, but found nothing.

No further mentions, no travel writing, no society column updates about his adventures abroad.

It was as if he had simply vanished from the historical record for several months.

Then in January 1896, another brief mention.

Mr.

Robert Morrison has returned to Charleston after his extended travels and has resumed his position with Morrison and company.

5 months abroad, leaving in July, 1 month before Sarah’s death in August, Maya pulled out her notebook and wrote.

April 1895, Thomas and Sarah have formal photograph taken.

July 1895, Robert Morrison suddenly leaves for Europe.

August 1895, Sarah dies of injuries from fall.

January 1896, Robert Morrison returns to Charleston.

She stared at the timeline, a terrible suspicion forming in her mind.

That afternoon, Maya visited the Charleston County Courthouse to search property records.

She found the deed for the Trad Street house, and attached to it, a household inventory from 1900 that listed all the Morrison family’s employed servants.

No, Sarah, of course not.

She had died in 1895, but there was another document, a handwritten note filed with the inventory.

Advanced payment made to Thomas Daniels, carpenter for household repairs and modifications.

March 1895.

Amount: $200.

$200 in 1895 was a fortune for a black carpenter, the equivalent of several months wages.

Maya’s hands shook slightly as she photographed the document.

Why would the Morrison family pay Thomas such a large sum just one month before Sarah left their employment? Was it payment for work? Or was it something else? Was it payment to take Sarah away, to marry her, and remove her from the house before something became obvious? Before questions could be asked? Mia thought again about that photograph, about Sarah’s desperate hand signal, about her death just four months later, and about Robert Morrison fleeing to Europe just in time to avoid being present when Sarah died.

Maya knew she needed to find Thomas Daniel’s own voice, his testimony, his words, his account of what happened.

She returned to Emanuel Church, hoping Reverend Johnson might help her access records she couldn’t find elsewhere.

Church minutes, Reverend Johnson suggested.

We kept detailed minutes of committee meetings, especially the Benevolent Society.

They helped congregation members in distress, raised money for funerals, supported widows and orphans, advocated when people were wronged.

They found the benevolent society records in a separate ledger, pages filled with names and abbreviated notes about cases the committee had taken on.

Maya’s heart raced as she turned the pages, searching for any mention of Thomas or Sarah Daniels.

Then, dated September 15th, 1895, 2 weeks after Sarah’s funeral, she found it.

Meeting called regarding Thomas Daniels petition for inquiry into death of wife Sarah.

Brother Daniels appeared before committee, testified that his wife suffered from no prior illness or weakness, stated she was frightened in final weeks, spoke of threats, but would not elaborate.

On morning of death, received message Sarah had fallen in Morrison household where she sometimes visited her former colleague Ruth.

Rushed the house, found Sarah unconscious.

Morrison family physician pronounced death from head injury.

Brother Daniels observed bruising inconsistent with fall, marks on wrists, defensive wounds on arms, requested formal investigation.

Committee decision given current climate and danger to colored citizens pursuing complaints against white families.

Advised Brother Daniels not to press matter further.

Risk of retaliation too great.

Raise collection to assist with funeral expenses and provided $45 to help brother Daniels established carpentry workshop in Columbia, South Carolina.

Advised immediate departure from Charleston.

Maya read it twice, three times, her chest tight.

They had paid Thomas to leave town.

The church itself, the people who should have been his advocates, had told him to run rather than seek justice for his murdered wife.

Because that’s what this was.

Sarah hadn’t fallen.

She had been killed.

Maya looked up at Reverend Johnson, who was reading over her shoulder his expression grave.

“They were protecting him,” he said quietly.

“In 1895, if a black man accused a white family of murder, even with evidence, he would have been lynched.

The committee knew that.

They were trying to save his life.

But what about Sarah’s life? What about justice for her? There was no justice for black women in 1895, Reverend Johnson said, his voice heavy with old anger and old grief.

Especially not against white men of prominent families.

The committee did what they thought they had to do.

Save the person they still could save.

Maya thought about Thomas, forced to flee his home, his community, his church, to escape retaliation for daring to question his wife’s death.

She thought about Sarah, dead at 26, her murder covered up as an accident forgotten by history.

except she hadn’t been completely forgotten.

Because she had left a message, a signal preserved in that photograph.

I need to go to Columbia.

Maya said, “I need to find out what happened to Thomas after he left Charleston.

” Reverend Johnson nodded.

I have contacts at churches in Colombia.

Give me a day and I’ll make some calls.

That evening, Maya sat in her apartment, the photograph of Thomas and Sarah propped against her laptop.

She studied Sarah’s face again, seeing it differently now.

Not blank, not vacant, but carefully controlled, desperately controlled, hiding terror behind a mask of composure.

How long had Sarah known she was in danger? Had Robert Morrison assaulted her when she worked in his house? Had she become pregnant, making the situation impossible to hide? Had the marriage to Thomas been arranged to cover it up? And then, when that wasn’t enough, had they killed her to ensure her silence forever? Maya would probably never know all the details.

But she knew enough.

She knew Sarah had been desperate enough to risk leaving a distress signal in a formal photograph, knowing it might be the only evidence that survived her.

And now, 129 years later, someone had finally seen it.

The drive to Columbia took 2 hours through flat coastal lands gradually rising toward the Midlands.

The landscape shifting from marshes and live oaks to pine forests and red clay.

Maya had an address, or rather a neighborhood where Thomas Daniels might have established his carpentry workshop in late 1895.

Reverend Johnson’s contact in Columbia was Pastor Ruth Williams of Bethlme Church, a woman in her 70s with silver braids and sharp intelligent eyes.

She met Maya in the church office which smelled of coffee and old paper.

Reverend Johnson told me about your research, Pastor William said.

I pulled what records we have from the 1890s.

We don’t have much.

There was a fire in 1902 that destroyed part of the building, but I found something interesting.

She placed a small worn notebook on the desk between them.

The cover was leather, cracked with age.

Inside, someone had kept careful accounts, names, dates, amounts of money.

This was Reverend Thomas Nathaniel’s record book, Pastor Williams explained.

He served here from 1893 to 1905.

He kept track of every member of the congregation, every baptism, every wedding, every burial, and he noted when members arrived from other places.

She turned pages until she found an entry dated October 1895.

Thomas Daniels, Carpenter, arrived from Charleston with letter of introduction from Reverend Patterson of Emanuel AM.

Brother Daniels has suffered great loss.

Wife Sarah murdered by white family.

Death falsely recorded as accident.

Brother Daniels sought justice but forced to flee due to threat of lynching.

Welcomed into our community.

Provided room at boarding house in Washington Street.

Committee raised funds to help establish workshop.

Maya felt her eyes burning.

Murdered.

The words she had been circling around afraid to say definitively.

Written plainly in this old record book.

Another reverend.

Another black church leader documenting what the white authorities had refused to acknowledge.

Is there anything else about him? Maya asked.

Pastor Williams nodded, turning more pages.

He stayed in Colombia for three years.

The records show he was a skilled carpenter.

The church hired him to repair our pews in 1896, build new cabinets in 1897.

He was active in the congregation, reliable, well-liked, but but he was also deeply damaged.

Reverend Nathaniel wrote several pastoral notes about counseling brother Daniels through his grief and anger.

Here, March 1896.

Brother Daniels struggles with nightmares.

still speaks of his beloved Sarah, of his failure to protect her, assured him her death was not his fault, but he cannot forgive himself for surviving.

Maya’s throat tightened.

She thought of Thomas receiving that $200 payment from the Morrison family, probably believing it was for legitimate carpentry work, not knowing it was payment for taking Sarah off their hand.

She thought of him arriving at the Morrison house to find his wife dead, seeing the bruises and defensive wounds, knowing immediately what had happened, but being powerless to speak the truth.

“When did he leave Columbia?” Ma asked.

Pastor Williams turned to a later page, 1898.

No forwarding address.

Reverend Nathaniel noted, “Brother Daniels departed for Chicago to join the great migration north, prayed for his safe journey and healing from his wounds, both visible and invisible.

He carries Sarah’s memory like a stone.

Chicago.

” The Great Migration wouldn’t fully begin for another two decades, but already black southerners were fleeing north, seeking safety, opportunity, escape from Jim Crow terror.

Did he stay in touch with the church? Not that I can find.

Once people left, communication was difficult.

Letters got lost.

Addresses changed.

Pastor Williams closed the record book gently.

But I’ll tell you what I think based on 40 years of ministry.

Thomas Daniels never stopped grieving for Sarah.

He never stopped blaming himself.

And he probably never spoke her name again to anyone who didn’t already know their story.

Maya drove back to Charleston as the sun set, painting the sky orange and red.

She thought about trauma passed down through generations, about stories lost because they were too painful to tell.

about justice denied so completely that even speaking about injustice became dangerous.

But she also thought about resistance, about Sarah’s defiant hand signal, about Thomas’s desperate attempt to get authorities to investigate, about the church communities that documented the truth.

Even when the official record lied, Sarah’s story had survived, hidden in plain sight for 129 years.

Now Mia had to decide what to do with it.

Mia spent three weeks writing.

She worked late into the nights in her apartment, surrounded by photocopies of documents, photographs, timeline notes spread across every surface.

The ceiling fan turned overhead, barely disturbing the thick air that pressed against the windows like the weight of history itself.

She wrote about Sarah, about her life as a domestic worker in a white household, about the vulnerabilities black women faced in 1890s Charleston.

She wrote about the photograph and its hidden signal, about Thomas’s testimony and the church’s desperate attempt to save his life by sending him away.

She wrote about the Morrison family and Robert Morrison’s convenient departure to Europe, about the $200 payment and the covered up murder.

She wrote about how history had failed Sarah.

How the official records called her death an accident.

How no newspaper mentioned it.

How she had been erased as thoroughly as if she had never existed except for that photograph except for that one desperate signal frozen in time.

Maya submitted the article to the Journal of Southern History, a peer-reviewed academic publication that reached historians, researchers, and educators across the country.

She included highresolution scans of the photograph, transcriptions of all the documents she had found, and a detailed methodology explaining her research process.

The article was titled, “Hidden in plain sight, Sarah Daniels and the Silent Testimony of the 1895 Charleston photograph.

” 6 weeks later, the journal accepted it for publication.

But Maya knew an academic article wasn’t enough.

Most people would never read the Journal of Southern History.

Sarah’s story needed to reach beyond academic circles.

It needed to be accessible, sharable, visible.

She contacted the Charleston Historical Society’s director and proposed an exhibition, Unspoken Truths, Hidden Messages, and Historic Photographs.

The centerpiece would be Sarah’s photograph, accompanied by panels, explaining the hand signal, Thomas’ testimony, the historical context of violence against black women in the post reconstruction south.

The director, Dr.

Patricia Holloway, a black woman in her 50s who had spent her career documenting Charleston’s African-American history, immediately said, “Yes, this is exactly the kind of story we need to tell.

” Dr.

Holloway said when they met to discuss the exhibition, “The stories that make people uncomfortable, that challenge the sanitized version of history, Sarah deserves to be remembered.

” The exhibition opened in October, exactly 129 years after Thomas Daniels had fled Charleston for Colombia.

The opening night drew more than 300 people, historians, descendants of Charleston’s black community, educators, journalists.

Maya stood near the photograph, watching people lean close to examine Sarah’s hand, seeing the moment when they understood what they were looking at.

She saw tears, anger, recognition, grief.

A local television news crew interviewed her.

Why is this photograph important? The reporter asked.

Maya looked at Sarah’s image.

Because for 129 years, Sarah has been waiting for someone to see her message, to acknowledge what happened to her.

History tried to erase her, to reduce her death to a footnote that said, “Fell.

” But she refused to be erased.

She left evidence.

She fought back the only way she could by making sure that someday someone would know the truth.

The story went viral.

First, local news, then regional, then national outlets picked it up.

Social media exploded with people sharing the photograph, expressing outrage at Sarah’s murder, connecting it to contemporary discussions about violence against black women, about cases that go uninvestigated, about how the criminal justice system fails victims.

Within a week, Maya was receiving messages from across the country, from historians who had similar photographs in their collections, and we’re now examining them more carefully, from genealogologists trying to trace connections to Sarah or Thomas, from educators wanting to use the story in their classes.

And then two weeks after the exhibition opened, Maya received an email that changed everything.

The subject line read, “I think Thomas Daniels was my great great-grandfather.

” Jerome Washington was a high school history teacher in Chicago, a thoughtful man in his 40s with graying temples and his ancestors same careful, kind eyes.

He had seen the news story about Sarah’s photograph and immediately recognized the surname Daniels that had been passed down in his family along with fragments of a painful story never fully told.

Maya met him at a coffee shop in Charleston’s historic district.

Jerome had flown in specifically for this meeting, bringing with him a folder of family documents and photographs.

My great great-grandfather, Thomas Daniels, came to Chicago from South Carolina in 1898, Jerome explained, spreading papers on the table between their coffee cups.

Family legend said he had been married before and lost his wife in a tragedy he never wanted to talk about.

He remarried in Chicago around 1902, had children, built a successful carpentry business, but he apparently had nightmares for the rest of his life.

My great-grandfather remembered him crying out in his sleep, calling a woman’s name, “Sarah.

” Jerome’s hands trembled slightly as he pulled out a small, faded photograph.

“This was in my grandmother’s belongings.

I never knew what it was until I saw your article.

” Maya took the photograph carefully.

It showed an older Thomas, probably in his 60s, standing in what looked like a woodworking shop.

Behind him, barely visible on the wall, was a framed photograph.

Maya pulled out her magnifying glass and examined the image on the wall.

It was Sarah.

The same photograph from 1895, the one Mia had found in the Charleston Historical Society archives.

“He kept her picture his whole life,” Maya whispered.

“He never forgot her.

” Jerome’s eyes were wet.

“When I saw your article, “When I read about what happened to Sarah, I finally understood why my great great-grandfather was the way he was.

why he never talked about his past.

Why he threw himself into his work like a man trying to outrun something.

He was trying to outrun guilt, Maya said gently.

Survivors guilt.

The church records from Colombia said he blamed himself for not protecting Sarah.

But how could he have protected her? Jerome’s voice broke.

A black man in 1895, Charleston up against a white family.

He would have been lynched if he tried to fight for her.

He did the only thing he could do.

He survived.

He carried her memory and he passed down a legacy even if he couldn’t talk about it directly.

Maya spent the rest of the day with Jerome, sharing everything she had discovered.

They visited the historical society exhibition together.

Jerome stood in front of Sarah’s photograph for a long time, tears running down his face.

“Thank you,” he finally said.

“Thank you for seeing her, for not letting her be forgotten.

” That evening, Dr.

Holloway arranged for Jerome to speak at a special program at the historical society.

More than 100 people came to hear him talk about his great great-grandfather, about the trauma that had echoed down through generations of his family.

For 129 years, my family carried this grief without fully understanding it.

Jerome said, “We knew Thomas had been damaged by something, but we didn’t know what.

Now we know, and knowing the truth, as painful as it is, is better than not knowing.

It helps me understand my own father, who struggled with depression.

My grandfather, who could never talk about feelings, the weight of Thomas’s trauma has been passed down generation after generation.

” He paused, composing himself.

But so has his resilience.

Thomas didn’t just survive.

He built a life, raised a family, contributed to his community.

He carried Sarah with him, honored her memory in the only way he could, and now finally we can honor her, too.

We can say her name.

Sarah Daniels.

She lived, she mattered, and she will not be forgotten.

The audience rose in standing ovation.

Maya watched from the back of the room, thinking about how history works, how the past reaches into the present, how truth, no matter how long buried, eventually finds its way to light.

6 months after the exhibition opened, Maya stood in front of Magnolia Cemetery’s office, a small building near the entrance where records were kept.

She had called ahead, explaining what she was looking for.

The cemetery manager, an elderly white man named Mr.

Harrison, met her with a large leatherbound register.

The colored section is in the back, he said, his tone neutral but not unkind.

Segregated, of course.

That’s how it was.

Records are sparse.

Many graves were never properly marked.

They walked through the cemetery together, following winding paths beneath live oaks draped in Spanish moss.

The air was thick and still, heavy with the scent of magnolia blossoms.

In the older sections, elaborate monuments marked the graves of Charleston’s white elite, family mausoleiums, marble angels, inscriptions celebrating lives of prominence and privilege.

The colored section was different.

Smaller stones, many cracked or fallen, graves marked with simple concrete blocks, or in some cases nothing at all.

just depressions in the earth where the ground had settled over forgotten coffins.

Mister Harrison consulted his register here.

Sarah Daniels buried August 30th, 1895.

Plot 247.

They found it in a far corner beneath a massive oak tree.

There was no headstone, just a small concrete marker level with the ground so weathered the name was barely visible.

Weeds grew thick around it.

Maya knelt and cleared away the weeds with her hands.

She traced the faint letters with her fingers.

Sarah, I’m going to make sure you get a proper memorial,” she said quietly.

“Everyone will know your name.

Everyone will know what happened to you.

” And she kept that promise.

Through crowdfunding and donations inspired by the exhibition, Mia raised enough money to commission a proper headstone for Sarah’s grave.

The marker was granite, elegant, and lasting with an inscription she and Jerome had written together.

Sarah Daniels C.

1869, August 1895.

She spoke her truth in silence.

We hear her now in thunder.

Beloved wife, remembered always.

The dedication ceremony took place on a warm April morning 130 years after Sarah’s photograph had been taken.

Jerome came from Chicago with his family.

His wife, his three daughters, his elderly father, who was Thomas’s great-grandson.

Members of Emanuel Church attended along with representatives from churches in Colombia and Chicago, connecting the communities that had sheltered Thomas in his grief and exile.

Pastor Williams gave the invocation.

Reverend Johnson read from scripture.

Jerome spoke about family, memory, and the long journey toward justice.

Maya was the last to speak.

She talked about the photograph, about the moment she had noticed Sarah’s hand signal, about the investigation that followed.

She talked about how easy it is to overlook the testimony of black women, to dismiss their voices, to erase their stories, but how Sarah had refused to be erased, how she had left a message that survived 130 years waiting to be heard.

Sarah could not speak out loud in 1895.

Ma said if she had accused Robert Morrison, she would have been ignored at best, punished at worst.

If she had told her husband what was happening before their photograph was taken, Thomas might have confronted Morrison and been lynched.

So Sarah did the bravest, smartest thing she could do.

She left evidence.

She made sure that someday, somehow someone would see her distress signal and ask questions.

Today, we answer those questions.

We say, “Yes, Sarah, we see you.

Yes, we believe you.

Yes, we honor your courage.

And yes, we will tell your story so that other women who have been silenced, erased, and forgotten will know that their voices matter, too.

” After the ceremony, people placed flowers on Sarah’s grave.

Liies, roses, wild flowers.

Jerome’s youngest daughter, a girl of 10, with Thomas’s same steady gaze, knelt and placed a small toy angel next to the headstone.

“So she won’t be alone anymore,” the girl said.

Maya thought about all the Sarah Daniels who had lived and died in obscurity, whose stories had been lost, whose voices had been silenced.

She thought about how history is written by those with power, how the official record so often erases the testimonies of the vulnerable and oppressed.

But she also thought about resistance, about the countless ways people find to leave evidence to speak truth even in silence.

Sarah’s hand signal, Thomas’s testimony to the church committee.

The reverends who wrote the truth in their private records, all of them creating an alternative archive, a counternarrative that survived even when the official history tried to erase it.

That evening, Maya sat in her apartment, the lights of Charleston Harbor glittering beyond her window.

She opened her laptop and began writing a new article about other photographs in the historical society collection.

Other images she was examining more carefully now, looking for details she might have missed, looking for other voices waiting to be heard, other stories demanding to be told.

The photograph of Thomas and Sarah sat propped against her monitor.

Maya looked at Sarah’s face, no longer blank to her eyes, but fierce, determined, speaking across the centuries.

News

🔥 Tatiana Schlossberg at 35: Cause of Death Revealed—What Her Husband Endured, How Her Children Were Shielded, and Why Her Low-Key Lifestyle Hid a Fortune No One Talked About 💥 Said with sharp, tabloid bite, the lead suggests the truth cuts deeper than headlines, as insiders hint at hospital corridors, late-night decisions, and a family scrambling to protect legacy while mourning a loss that money, status, and history couldn’t stop 👇

The Untold Tragedy of Tatiana Schlossberg: A Life Shattered Tatiana Schlossberg, a name that once resonated with promise and legacy,…

💔 Dad Didn’t Understand Why His Daughter’s Grave Kept Growing—Until a Hidden Truth Shattered Him and Exposed a Silent Ritual That Left Him Collapsing in Tears at the Cemetery Gates 😭 The narrator whispers with cruel suspense, hinting that what began as confusion turned into a devastating revelation, as the father learns strangers had been secretly visiting, leaving objects, soil, and symbols that transformed grief into a haunting testament of love he never knew existed 👇

The Unraveling of a Legacy Tatiana Schlossberg was not just a name; she was a symbol of a storied lineage,…

💔 BREAKING: JFK’s Granddaughter Dies at 35—A Kennedy Tragedy Rewrites History Again as Tatiana Schlossberg’s Sudden Passing Sends Shockwaves Through a Family Long Haunted by Loss, Leaving America Whispering About Fate, Fragility, and the Price of a Legendary Name The narrator purrs with dramatic disbelief, hinting that this isn’t just another sad update but a chilling reminder that even America’s most storied dynasty cannot outrun sorrow, as insiders describe stunned relatives, hushed phone calls, and a grief so heavy it feels almost scripted by destiny itself 👇

The Unraveling of a Legacy Tatiana Schlossberg was not just a name; she was a symbol of a storied lineage,…

💐 At 35, Tatiana Schlossberg, JFK’s Granddaughter, Laid to Rest—Her Husband’s Heartbreaking Tribute Leaves Family, Friends, and the Nation in Tears as Funeral Honors a Life of Promise, Legacy, and Tragedy Cut Far Too Short The narrator leans in with emotional intensity, insisting this isn’t just a ceremony but a moment of raw grief, love, and history colliding, as tearful attendees, solemn prayers, and intimate reflections reveal the depth of heartbreak no one could ignore 👇

The Shattered Legacy of Tatiana Schlossberg In the heart of a cold January morning, Tatiana Schlossberg, the granddaughter of the…

🔥 Shock and Sorrow: JFK’s Grandchild Tatiana Schlossberg Dies at 35, Leaving Family, Friends, and Admirers Grappling With Sudden Tragedy Delivered with tabloid intensity, the lead teases that grief mixes with disbelief, as her vibrant life, intellect, and promise vanished suddenly, leaving hearts broken and minds searching for answers 👇

The Fallen Star: A Kennedy’s Legacy Shattered In the heart of a winter morning, the world learned of a tragedy…

💐 Remembering JFK’s Granddaughter Tatiana Schlossberg—A Life of Promise, Legacy, and Heartbreak That Ended Far Too Soon, Leaving Family, Friends, and a Nation Mourning the Loss of a Bright Young Life The narrator leans in with somber, dramatic intensity, insisting this isn’t just tribute but a reflection on a family shaped by history, grief, and courage, as memories, accomplishments, and private moments paint the portrait of a life tragically cut short 👇

The Shadow of Legacy: The Untold Story of Tatiana Schlossberg In the heart of New York City, the legacy of…

End of content

No more pages to load