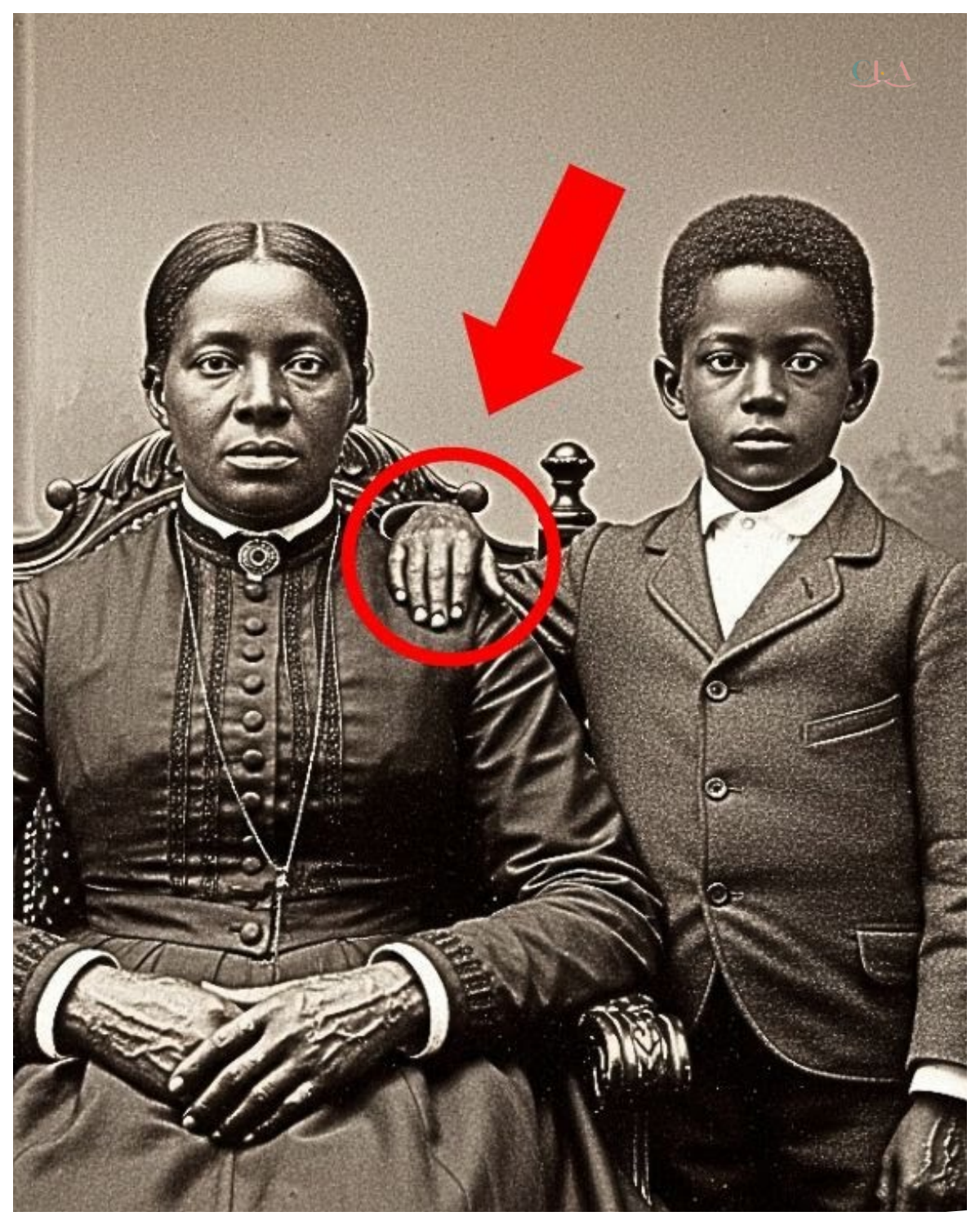

It was just a portrait of a mother and son from 1895.

But look closer at their hands.

The photograph measured exactly 8 in x 10, its edges browned and curled with age.

It sat in a cardboard box marked Atlanta collection, uncataloged in the basement archives of the Georgia Historical Society, surrounded by thousands of other images that had waited decades for someone to notice them.

Dr.

Sarah Mitchell had been working through the collection for three months when she pulled the portrait from its protective sleeve on a humid Tuesday morning in June 2018.

The image showed a black woman and a boy, perhaps 12 years old, posed formally in what appeared to be a professional photography studio.

The woman sat rigidly in a highbacked chair, her expression dignified and unreadable.

The boy stood beside her, one hand resting on her shoulder, his face equally composed.

Sarah almost placed it back in the box.

Portrait photography from the 1890s was common enough in the archives, and this one seemed unremarkable at first glance.

Just another family commissioning a formal photograph, something that had become more accessible to black families in the South during that brief window after reconstruction, but before Jim Crow laws fully tightened their grip.

But something made her pause.

She held the photograph closer to the LED lamp on her desk, squinting at the details.

The studio backdrop showed painted columns and draped fabric, typical of the era.

The woman wore a dark dress with a high collar, modest and proper.

The boy was dressed in what looked like his Sunday best, a simple jacket and pressed shirt.

Sarah reached for her magnifying glass, a habit she had developed during her graduate studies.

She scanned across the image slowly, examining the composition, the lighting, the way the photographer had positioned his subjects.

Then she moved to their hands.

The woman’s hands rested in her lap, fingers interlaced.

The boy’s free hand hung at his side.

Sarah leaned closer, her breath catching slightly.

There was something there, something she couldn’t quite make out with the naked eye.

She rolled her chair across the small archive room to where the digital scanner sat on a metal table.

Carefully, she placed the photograph face down on the glass surface and closed the lid.

The machine hummed to life and bright light swept beneath the image.

On her computer screen, the photograph appeared in high resolution.

Sarah zoomed in on the hands.

First the mothers, then the sons.

Her pulse quickened.

That’s impossible, she whispered to the empty room.

The marks were faint but unmistakable once magnified.

On both sets of hands, running across the fingers and palms were patterns of scarring and calluses that seemed deliberate, almost methodical.

They weren’t the random marks of labor or injury.

They were specific, intentional.

Sarah grabbed her phone and took a photo of the screen, then immediately texted her colleague at Emory University.

Need you to see something.

Can you come to the archives today? The response came within seconds.

On my way.

Sarah sat back in her chair, staring at the image on her screen.

The woman’s face remained impassive, revealing nothing, but her hands.

Those hands told a different story entirely.

A story that, according to everything Sarah knew about 1895 Georgia, should never have existed.

Dr.

James Crawford arrived at the archives 40 minutes later, slightly out of breath from climbing the stairs two at a time.

He was a medical historian specializing in African-American health practices in the post civil war south, and Sarah had worked with him on two previous research projects.

Show me, he said, not bothering with pleasantries.

Sarah pulled up the magnified image on her screen.

James leaned in close, adjusting his glasses.

For a long moment, he said nothing.

Then he pulled a chair beside her and sat down heavily.

Where did you find this? Atlanta collection.

It’s been sitting in a box since the 1960s, maybe longer.

There’s almost no documentation with it.

Sarah handed him a small index card that had been tucked behind the photograph.

This is all we have.

The card was yellowed and brittle.

In faded pencil, someone had written portrait woman and boy C.

Thompson Studio Atlanta circa 1895.

No names? James asked.

Nothing, just that.

James turned back to the screen, zooming in further on the woman’s hands.

These marks, he said slowly, tracing a finger along the screen.

Look at the pattern here along the index and middle fingers and these calluses on the palms.

See how they’re positioned? Sarah nodded.

I noticed that.

What do you think they mean? James was quiet for another moment, his eyes moving across every detail of the magnified image.

Then he zoomed to the boy’s hands.

The same patterns appeared, though less pronounced, newer, perhaps.

I think, James said carefully.

These are tool marks.

Specific tool marks from medical instruments.

Sarah felt her stomach tightened.

Medical instruments in 1895.

Look here.

James pointed to a particular scar on the woman’s right index finger.

This pattern is consistent with repeated use of a scalpel or surgical blade.

In these calluses on her thumbs, they’re positioned exactly where you’d grip forceps or clamps for extended periods.

But that would mean that she was performing medical procedures.

James finished regularly for years based on how developed these marks are.

They both fell silent, the weight of the implication settling over them.

In 1895, Georgia, the idea of a black woman practicing medicine was not just unusual.

It was essentially illegal.

The state had strict licensing laws and medical schools were closed to black students, especially women.

The few black doctors who did exist in the south had trained in the north or in rare institutions like Howard University in Washington.

What about the boy? Sarah asked.

James zoomed back to the son’s hands.

His marks are less developed, but they’re there.

Same positions, same patterns, newer scarring.

She was training him.

It looks that way.

Sarah stood and began pacing the small room, her mind racing through the implications.

If this is real, if she really was practicing medicine, then we’re looking at something extraordinary.

An entirely undocumented medical practice operated by a black woman in the deep south during the height of segregation.

James pulled out his phone and began taking photos of the screen.

We need to find out who she was.

The studio name is Thompson.

C.

Thompson.

There can’t have been that many black photography studios in Atlanta in 1895.

There weren’t many photography studios, period, Sarah said.

Most black families couldn’t afford formal portraits.

The fact that she commissioned one at all suggests she had some means, some standing in the community.

Or James added, she wanted to leave a record.

People don’t usually pose with their working hands prominently displayed in formal portraits.

Look at how she’s positioned them right in the center of the frame, clearly visible.

It’s almost like she wanted someone to notice.

Sarah returned to her desk and pulled out a thick reference book on Southern Photography Studios.

She flipped through the index, running her finger down the list of names.

Thompson.

Thompson here.

Thompson Charles, African-American photographer, operated studio on Auburn Avenue, Atlanta, 1892, 1903.

Auburn Avenue, James said.

That was the heart of black Atlanta.

If she was wellknown in the community, someone would have known about her work.

Uh, but why isn’t there any record? No newspaper mentions, no city documents, nothing.

James looked back at the photograph, at the woman’s composed, dignified expression.

Because what she was doing was illegal.

She would have been operating completely underground, serving her community in secret.

Sarah spent the rest of the afternoon combing through the archives for any documentation related to Charles Thompson’s photography studio.

The Georgia Historical Society had several boxes of materials from Auburn Avenue businesses, but most focused on the early 20th century after Thompson’s studio had closed.

She found a business directory from 1896 that listed C.

Thompson, photographic portraits, with an address on Auburn Avenue between Piedmont and Boulevard.

She made a note of the location, knowing that the neighborhood had been transformed multiple times since then, most notably during the construction of the interstate highway system in the 1960s that had torn through the heart of black Atlanta.

James, meanwhile, had gone to Emory’s medical library to research surgical techniques and instruments from the 1890s.

He wanted to compare what they were seeing in the photograph with what would have been standard medical practice during that period.

By evening, they reconvened at a coffee shop near the university, spreading their notes across a corner table.

I found something interesting, James said, pulling out a printed article.

This is from the Journal of the National Medical Association published in 1912.

It’s an oral history project interviewing elderly black residents about healthcare practices in Atlanta during the previous decades.

He pointed to a specific passage.

Sarah read aloud, “Many in our community relied on traditional healers and midwives for medical care, as licensed physicians were scarce and often refused to treat colored patients.

One respondent, whose name is withheld, mentioned a woman on Auburn Avenue, known for her skill and difficult births and her knowledge of healing.

This woman reportedly learned her craft from her mother, who had been enslaved on a plantation where she assisted the master’s physician.

“That could be her,” Sarah said, feeling a surge of excitement.

“There’s more.

Listen to this part.

” The respondent stated that this woman trained her son in her methods, hoping he might one day attend medical school in the north.

though this apparently never came to pass.

Sarah sat back in her chair.

So, she had ambitions for him.

She wasn’t just practicing medicine herself.

She was trying to create a legacy.

But something stopped it, James said.

He never made it to medical school.

The question is why? Sarah pulled the photograph from her bag, now encased in a protective clear sleeve.

She studied the boy’s face again.

His serious expression, the way he stood with his hand on his mother’s shoulder, a gesture that could be read as both protective and differential.

How old do you think he was when this was taken? She asked.

12, maybe 13, James estimated.

If the photo was from 1895, and if we can figure out what happened to him, we might be able to trace the story forward.

Or backward, Sarah added, “If her mother taught her, then this medical knowledge goes back at least to slavery times.

” “That’s three generations of medical practice, all undocumented,” James pulled out his laptop and opened a genealogy database.

“Let’s start with what we know.

Auburn Avenue, 1895.

a black woman with medical knowledge and a son about 12 years old.

Charles Thompson’s photography studio.

Thompson might have kept records, Sarah said.

Client logs, payment receipts, something.

If they survived, James cautioned.

A lot of black business records from that era were lost, either deliberately destroyed or just not preserved.

They worked in silence for several minutes, each pursuing different research threads.

Sarah searched through digitized city directories and census records.

James explored medical licensing documents and hospital records from the period.

Then Sarah’s screen froze on a particular entry.

James, look at this.

The 1900 federal census record appeared on Sarah’s laptop screen.

The handwritten entries barely legible even in their digitized form.

But one entry recorded for a residence on Auburn Avenue caught her attention immediately.

Head of household Clara Hayes, female, negro, age 38, occupation, midwife.

Sarah read aloud.

Living with her son, Daniel Hayes, male, negro, age 15, occupation, student.

James leaned over to see the screen.

The ages don’t match perfectly if the photo is from 1895, but census ages were often recorded incorrectly.

People didn’t always know their exact birth dates, especially if they had been born during slavery.

Clara Hayes, Sarah repeated, testing the name.

And Daniel midwife is listed as her occupation, James noted.

That was legal technically.

Midwiffery wasn’t regulated the same way as medicine.

But look, he pointed to a notation in the margin that had been added in different ink.

There’s something written here.

Sarah zoomed in on the faint marking.

Someone, perhaps the census taker or a later archivist, had added a small notation.

Known healer serves community.

Known healer, James said softly.

That’s more than just midwiffery.

Sarah was already searching for more records.

If we have her name, we can find more.

Property records, tax documents, church registries, death certificates, James added grimly.

If we can find when and how she died, it might tell us what happened to the practice.

They worked with renewed intensity, the coffee shop slowly emptying around them as evening turned to night.

Sarah found a property tax record from 1897 showing that Clara Hayes owned a small house on Auburn Avenue valued at $200, a significant sum for a black woman in that era, suggesting she had accumulated some wealth from her work.

James discovered a mention in the minutes of the Wheat Street Baptist Church dated 1893, noting that Sister Hayes had been recognized for her charitable works among the sick and afflicted.

Another church record from 1889 mentioned a donation from C.

Hayes in memory of her mother, Esther, who was called Home to Glory.

Her mother was Esther, Sarah said, adding the name to her growing notes.

That matches what the oral history said.

She learned from her mother.

But where did Esther learn? James wondered.

That’s the real question.

Where did this knowledge come from originally? Sarah pulled up a slave schedule from the 1860 census, searching for any record of an enslaved woman named Esther in the Atlanta area.

The records were fragmentaryary and often listed enslaved people only by age and gender, not names.

But in the schedule for a plantation owned by a family named Whitfield, 15 mi outside Atlanta, she found an entry that made her pause.

Female, negro, age 35, house servant, medical assistant to family physician.

Medical assistant, James said.

During slavery, that could mean anything from bringing supplies to actually assisting in procedures.

But if she was talented, if she had real skill, the physician might have taught her.

Sarah finished.

not out of kindness, but because he needed the help.

And then she would have taught her daughter, Clara, and Clara taught Daniel.

They sat back, letting the weight of what they were uncovering settle over them.

This wasn’t just one woman’s story.

It was a lineage of medical knowledge passed down through three generations, surviving slavery, reconstruction, and the violent reassertion of white supremacy in the South.

“We need to find out what happened to Daniel,” Sarah said.

“If Clara was training him, if she hoped he’d go to medical school, then his story is crucial.

” James nodded and resumed searching.

After another 30 minutes, he found something in the records of Howard University in Washington DC.

One of the few institutions that accepted black students for medical training in the late 19th century.

Application record, James said, his voice tight with excitement.

Daniel Hayes from Atlanta, Georgia, applied to the medical program in 1902.

Did he get in? Sarah asked, leaning close to see the screen.

James scrolled down to the notation at the bottom of the application.

His expression fell.

Application denied.

Reason given.

Insufficient preparatory education and questionable moral character.

Questionable moral character, Sarah said incredulously.

What does that mean? It could mean anything, James said bitterly.

Or nothing.

It could have been code for any number of things.

That he was too dark-kinned, that he came from the deep south, that someone wrote a negative reference.

Sarah and James spent the next several days following every lead they could find about Daniel Hayes’s rejected application to Howard University.

James had connections with the university’s archives and managed to request a full copy of Daniel’s application file.

When the documents arrived via email, they gathered in Sarah’s office to review them together.

The application, written in careful, slightly stilted handwriting on forms that had yellowed with age, painted a picture of a young man desperate for formal education.

Daniel had listed his preparatory education as private instruction in medical sciences and anatomy provided by his mother, Clara Hayes.

He noted that he had assisted in over 100 births and had practical knowledge of surgical procedures, pharmarmacology, and treatment of infectious diseases.

He was essentially claiming to have the experience of a medical apprentice, James observed, which technically he did, but without formal schooling or a licensed physician supervising him, Howard would never have accepted that.

The letter of reference attached to the application made the situation clearer.

It was written by Reverend Peter Simmons of Wheat Street Baptist Church and was carefully worded, “Daniel Hayes is a young man of good character and strong Christian faith.

He has expressed to me his earnest desire to serve his community through the practice of medicine, while his educational preparation has been unorthodox.

I have witnessed firsthand his dedication to learning and his gentle manner with the sick.

I believe he would be an asset to the medical profession if given the opportunity.

” “Unorthodox,” Sarah repeated.

That’s a diplomatic way of saying he learned everything from his mother outside any formal institution.

But it was the second letter in the file that explained the rejection.

It was written by Dr.

Marcus Whitfield, a white physician in Atlanta, and addressed to the admissions committee at Howard University.

Sarah read it aloud, her voice growing tighter with each sentence.

Gentlemen, I write to you regarding the application of a young negro named Daniel Hayes.

While I understand your institution seeks to elevate members of the colored race through education, I must warn you against this particular applicant.

His mother, who calls herself a healer, has been operating an illegal medical practice in Atlanta for many years, treating Negroes, and I’m sorry to say, some white patients who are unaware of her race and lack of credentials.

She has no formal training whatsoever and represents a danger to public health.

Her son has been complicit in these illegal activities.

Admitting such a person to your program would damage the reputation of your institution and the medical profession as a whole.

I trust you will reject his application accordingly.

The room fell silent.

James’ jaw was clenched, his hands flat on the desk.

Whitfield, he finally said, “That’s the same family name from the plantation records.

The family that owned Esther,” Sarah pulled up her earlier notes.

“You’re right.

” Marcus Whitfield would have been the grandson of the original plantation owner.

His father would have been the physician who worked with Esther.

So, he knew, James said.

He knew about Clara’s practice, knew where her knowledge came from, and he deliberately sabotaged Daniel’s application.

More than that, Sarah added, scanning the rest of the file.

Look at the date of this letter.

March 1902.

Now look at this.

She pulled up another document on her screen.

This is a complaint filed with the Atlanta Board of Health in April 1902, one month later, accusing an unnamed negro woman on Auburn Avenue of practicing medicine without a license.

He went after her, James said quietly.

When the letter to Howard didn’t stop Daniel, Whitfield went after Clara directly.

The question is, what happened next? Sarah said.

Did she stop practicing? Did they arrest her? James was already searching through criminal court records.

After several minutes, he shook his head.

No arrest record, no trial.

Either they dropped the complaint or or she went further underground, Sarah finished.

If she stopped advertising herself as a healer, if she worked only through word of mouth, only with people who already knew her, they might not have been able to build a case.

But it would have destroyed any chance Daniel had of getting formal training.

James pointed out, “No other medical school would touch him after that letter from Whitfield.

He would have been blacklisted.

” Sarah returned to the photograph on her screen, looking at Daniel’s young face, his hand resting on his mother’s shoulder.

So, what did he do? If he couldn’t go to medical school, if his mother’s practice was under scrutiny, where did he go? The answer came from an unexpected source.

Sarah had posted a query on a genealogy forum asking if anyone had information about Clara or Daniel Hayes from Atlanta in the early 1900s.

Three days later, she received a message from a woman named Beverly Patterson in Philadelphia.

My grandmother used to tell stories about her uncle who came up from Atlanta around 1903.

Beverly’s message read, “His name was Daniel, and she said he had learned healing from his mother, but could never become a real doctor because of the color laws down south.

I have some old family letters that mention him.

Would you like to see them?” Sarah immediately called Beverly, and the woman agreed to scan and send the letters.

When they arrived, Sarah and James poured over them in the archive room, the afternoon sun slanting through the high windows.

The letters were written between 1903 and 1907.

correspondence between Daniel and his cousin Ruth, who had remained in Atlanta.

Daniel’s handwriting was the same careful script from his Howard application, but the tone was more personal, more revealing.

In a letter dated June 1903, Daniel wrote, “Dear Ruth, I have found work in a hospital here, though not as I had hoped.

I work in the laundry and help move patients from ward to ward.

The white doctors do not speak to me except to give orders, but I watch them carefully.

I see how they examine patients, how they conduct themselves, what instruments they use.

Mother would be pleased to know that I am still learning, even if I cannot practice.

” Philadelphia is cold and crowded, but there are opportunities here that would never exist in it.

I pray for mother’s health and safety.

Please tell her that I am well and that I have not abandoned her teachings.

Um, he went to Philadelphia to work in a hospital, James said, not as a doctor, but at least he was in a medical environment.

Another letter from December 1904 was more somber.

Dear Ruth, thank you for your letter informing me of mother’s passing.

I knew her health had been declining, but I had hoped to see her once more.

You say she died peacefully in her sleep, surrounded by women she had helped bring into this world.

There is comfort in that.

You ask if I will return to Atlanta now that she is gone.

I cannot.

There is nothing for me there but memories and the knowledge that I was not permitted to follow the path she prepared for me.

Here at least I can be useful.

I have been teaching some of the colored orderlys basic medical procedures.

How to dress wounds properly.

How to recognize signs of infection, how to comfort patients in pain.

Mother’s knowledge will not die with her.

I will make sure of that.

Sarah felt tears prick her eyes.

He kept teaching.

Even though he couldn’t practice officially, he passed on what his mother taught him.

The final letter in the collection was dated September 1907 and its contents made both researchers sit up straighter.

Dear Ruth, I write with news that mother would have celebrated.

After four years working in the hospital, I have been promoted to the position of medical orderly in the colored ward.

It is not a doctor, but I am now permitted to assist with basic procedures under supervision.

More importantly, I have been accepted into the Frederick Douglas’s Memorial Hospital Nursing Program.

They have agreed to admit me based on my practical experience.

Though I am older than their usual students, it is not medical school, but it is formal training.

It is recognition.

When I complete the program, I will be a licensed nurse able to practice legally.

Mother always said that the work was more important than the title.

I am finally beginning to understand what she meant.

A nurse, James said, leaning back in his chair.

He couldn’t become a doctor, so he became a nurse.

And in 1907, that was still remarkable.

And male nurses were rare, especially black male nurses.

But he got his formal training, Sarah added.

After everything, the rejection, the persecution, his mother’s death, he found a way.

Beverly’s message had included one more piece of information.

According to family stories she had written, Uncle Daniel eventually came back to the south in the 1920s.

He worked as a nurse in several black hospitals and was known for training younger nurses in what he called the old methods, techniques his mother and grandmother had taught him.

He died in 1956 at the age of 71.

While James continued researching Daniel’s life in Philadelphia and his eventual return to the South, Sarah became increasingly interested in Dr.

Marcus Whitfield and his relationship to Clara Hayes’s family, there was something deeply personal in Whitfield’s letter to Howard University, a venom that went beyond professional concern or racial prejudice alone.

She drove out to the Georgia State Archives in Marorrow, where property records and family papers from old Atlanta families were housed.

The Whitfield family, being prominent and white, had left extensive documentation, wills, deeds, business records, and personal correspondence.

It took Sarah most of a day to locate the papers of Dr.

Samuel Whitfield, Marcus’ father, and the physician who had owned Esther during slavery.

The collection included a leatherbound journal spanning from 1855 to 1868, covering the years before, during, and after the Civil War.

Sarah pulled on cotton gloves and carefully opened the journal.

The handwriting was small and precise.

The entries dated, but often brief.

Dr.

Whitfield had been a methodical man, documenting his cases, his treatments, his successes and failures.

An entry from August 1861 caught her attention, performed emergency surgery on Mrs.

Thornton’s servant girl, who suffered a ruptured appendix.

The procedure was successful only because Esther assisted with such skill that I could work quickly and with confidence.

She has a natural aptitude for surgery that I have rarely seen in my white colleagues.

I have begun teaching her more advanced techniques.

She is invaluable to my practice.

Sarah photographed the page with her phone and kept reading.

As the war progressed, Dr.

Whitfield’s entries about Esther became more frequent and more revealing.

December 1862.

Esther delivered three babies this week without my supervision.

All survived, including one breach presentation that she managed expertly.

She is becoming known in the slave quarters as a healer in her own right.

March 1864.

Supplies are scarce, and I’m called away frequently to attend wounded soldiers.

Esther now manages most of the medical care for the plantation and surrounding farms.

Her daughter Clara, age 10, follows her everywhere and is learning at an astonishing rate.

I have decided to teach them both systematically.

When the war ends, assuming we survive, they may prove essential to rebuilding medical care in this region.

April 1865.

The war is over, and we have lost everything.

The plantation will likely be divided and sold.

I have told Esther that she is free to go, but I have asked her to continue working with me if she chooses.

I cannot pay her much, but I can continue her training.

She has agreed on the condition that I also train Clara formally.

I have consented.

Almost.

Sarah’s hands trembled slightly as she turned the pages.

This was it.

The origin of the knowledge that had passed through three generations.

Dr.

Whitfield had taught Esther not out of progressive ideals, but out of necessity, and yet in doing so, he had created something extraordinary.

But the journal entries from the late 1860s grew darker.

November 1867.

Esther informed me today that she will be leaving my practice.

She has purchased a small house in Atlanta with money she saved and she intends to continue healing work independently serving the colored community.

I tried to persuade her to stay, but she is determined.

I’m concerned about what will become of her without proper oversight.

January 1868.

I have heard troubling reports about Esther practicing medicine in Atlanta without a license.

I wrote to the medical board about this matter, but they showed little interest in regulating colored healers as long as they only treat their own people.

I fear she will eventually harm someone through her ignorance despite the training I provided.

The final entry about Esther was dated March 1868.

Esther came to my office today with Clara, now 16 years old.

She wanted to thank me for training them.

She said they are serving dozens of families who have no other access to medical care.

She asked if I would provide her with a letter of reference, some documentation of her training.

I refused.

I cannot in good conscience credential someone who has no formal degree, regardless of their practical skills.

She left angry.

I suspect I will not see her again.

Sarah sat back, the journal still open in front of her.

Doctor Samuel Whitfield had given Esther skills that saved countless lives, but he had also refused to give her the one thing that would have legitimized those skills in the eyes of the law.

Sarah found more pieces of the story in unexpected places over the following weeks.

A diary belonging to a white woman named Margaret Spencer, who lived in Atlanta in the 1890s, contained an entry that made Sarah’s heart race.

I was terribly ill with fever last month, and Dr.

Patterson could not determine the cause.

My maid mentioned that there was a colored woman on Auburn Avenue who was known for treating difficult cases.

In my desperation, I allowed myself to be taken to her house.

The woman, Clara, examined me with such thoroughess and knowledge that I was astonished.

She prescribed a combination of herbs and told me to drink large quantities of water boiled with certain roots.

Within 3 days, my fever broke.

I tried to pay her generously, but she would accept only a modest sum.

When I asked where she learned her skills, she said only that her mother had taught her.

I have told no one about this visit except this diary, as I would be criticized for seeking treatment from a negro, but I believe that woman saved my life.

James, meanwhile, had discovered references to Clara in the records of Grady Hospital, Atlanta’s main public hospital.

In 1899, the hospital had received several black patients who had been pre-treated by an unnamed healer before arrival.

The hospital’s chief physician had written a tur note in the log book.

These patients showed evidence of competent initial care, clean bandaging, proper spinting of fractures, and appropriate preliminary treatment of infections.

Staff should determine who is providing this care and whether it meets medical standards.

But the most revealing documents came from the papers of Dr.

William Penn, a black physician who had established a small practice in Atlanta in 1900, one of the very few licensed black doctors in the city.

Sarah found his papers at the Atlanta University Center archives.

Dr.

Penn had kept meticulous notes on his cases and his observations about healthcare in the black community.

In an entry from 1901, he wrote, “I have heard much about a woman named Clara Hayes who has been treating patients in the Auburn Avenue neighborhood for many years.

There is some controversy about her work.

She has no medical degree and is not licensed, but I decided to meet with her to assess the situation for myself.

I visited her home today, and what I found astonished me.

Mrs.

Hayes has more practical medical knowledge than many licensed physicians I know.

Her home contains a clean, wellorganized treatment room with proper instruments, medications, and supplies.

She showed me her records, detailed notes on hundreds of cases spanning more than a decade.

Her diagnostic abilities are remarkable.

She can identify diseases by observation and palpation with an accuracy that suggests years of training.

When I asked about her education, she explained that her mother learned from a white physician before and after the war, and she herself learned from her mother.

She also told me about her son who assists her and who she hopes will someday attend medical school.

I left her home with mixed feelings.

What she is doing is technically illegal.

Yet, she is providing essential care to hundreds of people who would otherwise have no access to treatment.

I have decided not to report her to the authorities.

The community needs her too much.

Sarah called James immediately after finding this entry.

We have confirmation from a licensed black physician that Clara was legitimate.

This isn’t just folklore or family legend.

Dr.

Dr.

Penn witnessed her work firsthand and validated her skills, which makes what Marcus Whitfield did even worse, James replied.

He wasn’t protecting public health or medical standards.

He was protecting white supremacy.

He couldn’t stand the idea of a black woman, especially one whose grandmother, his own father, had enslaved, having real medical knowledge and authority.

They met that evening to compile everything they had learned.

Spread across Sarah’s dining table were photocopies, photographs, scanned documents, and pages of notes.

The story was coming together, but there were still gaps.

We know Clara practiced medicine in Atlanta from at least the early 1890s until her death in 1904, Sarah said, organizing the documents into chronological order.

We know she trained Daniel, and we know Marcus Whitfield sabotaged his medical school application and tried to shut down her practice.

And we also know Daniel eventually became a nurse and carried on his mother’s teachings, James added.

But what we don’t know is how extensive Clara’s practice actually was.

How many people did she treat? How many lives did she save? And Sarah said quietly, looking at the 1895 photograph that had started everything.

We don’t know why she had this photograph taken.

What was she trying to preserve or communicate? The answer to why Clara Hayes had commissioned the photograph came from an unlikely source.

A conversation with an elderly woman named Josephine who volunteered at the Wheat Street Baptist Church where Sarah had gone to research the church’s historical records.

My great-grandmother used to tell stories about the old days on Auburn Avenue.

Josephine said when Sarah mentioned Clara’s name, she said there was a healer woman who everyone knew about but nobody talked about openly because the white folks didn’t like it.

Said this woman was smart, real smart, and she knew she couldn’t write down what she knew because if the authorities found written medical records, they’d use it against her.

So how did she preserve her knowledge? Sarah asked already sensing the answer.

She taught it, Josephine said simply.

Taught her son everything.

Made him practice until his hands knew what to do without thinking.

My great-grandmother said this woman told people that the knowledge was in the hands.

That’s where the real learning lived, in the muscle memory and the calluses and the scars from a thousand procedures.

Sarah felt something click into place.

She thanked Josephine and called James immediately.

The photograph, she said before he could even say hello.

It wasn’t just a family portrait.

It was documentation.

And what do you mean? Think about how they’re posed.

Clara’s hands are prominently displayed in her lap, clearly visible.

Daniel’s hands are positioned where the camera can capture them.

And look at their expressions.

They’re not smiling or trying to look pleasant.

They’re serious, dignified, almost formal.

It’s like they’re saying, “This is who we are.

This is what we do.

Look at our hands.

” James was quiet for a moment.

You think she knew that she couldn’t keep written records, so she created a visual record instead.

More than that, Sarah said, the pieces falling into place rapidly.

I think she knew that Daniel might not be allowed to pursue formal medical training.

She knew that Marcus Whitfield or someone like him might try to erase their work, their knowledge, their entire contribution.

So she created evidence that couldn’t be destroyed or confiscated.

A photograph that would survive even if everything else was lost.

A photograph that showed their hands, James said, understanding now.

The hands that delivered babies, sutured wounds, set broken bones, prepared medicines.

The hands that carried three generations of medical knowledge.

Sarah pulled up the highresolution scan of the photograph on her laptop.

She zoomed in on Clara’s hands than Daniels.

The marks were clearer now that she knew what she was looking at.

The specific patterns of scarring and callousing that came from years of using surgical instruments.

the subtle thickening of certain fingertips from palpating for tumors and swollen glands.

The slight deformity of one of Clara’s knuckles that might have come from a broken bone that healed while she continued working.

“These hands,” Sarah said softly, are a medical education captured in a single image.

They’re proof of skill, of practice, of dedication.

They’re everything that a medical degree was supposed to represent, but that Clara and Daniel were never allowed to have.

Over the next week, Sarah and James worked with a medical illustrator to create detailed diagrams of the marks visible on Clara and Daniel’s hands, comparing them with known patterns of occupational scarring in medical professionals from the late 19th century.

Every mark, every callous, every subtle deformity told a story of specific procedures performed hundreds of times.

The illustrator, Dr.

Rebecca Chen, was fascinated by the project.

I work with surgeons all the time, she said.

And I can tell you that these patterns are absolutely consistent with someone who performed surgical procedures regularly.

Look at this scarring on Clara’s left index finger.

That’s exactly where you’d get cut if you were doing emergency surgery with a scalpel and your hand slipped slightly and these calluses on both their thumbs.

That’s from gripping surgical clamps for extended periods.

This woman wasn’t just treating minor ailments.

She was performing serious medical procedures.

James had been working with a statistician to estimate based on the historical records they’d found how many patients Clara might have treated during her career.

The numbers were staggering.

If she practiced for approximately 25 years from roughly 1880 to 1904, and if she averaged even just two patients per day, which is conservative based on Dr.

Penn’s notes suggesting she was very busy, that’s over 18,000 patient encounters.

If we estimate that she attended even just five births per month, that’s 1,500 deliveries over her career.

1/5 hundred lives she brought into the world, Sarah said, and probably hundreds of lives she saved through treatment of infections, injuries, and diseases.

And all of it undocumented, James added, except for this one photograph.

Sarah and James research culminated in a major exhibition at the Georgia Historical Society titled Hidden Hands: The Untold Story of Black Medical Practice in Post Reconstruction Atlanta.

The centerpiece was the 1895 photograph of Clara and Daniel Hayes, displayed alongside all the documentation they had uncovered about their lives and work.

The opening night drew a crowd larger than the historical society had ever seen.

Descendants of the Auburn Avenue community came.

Some bringing their own family stories of healers and midwives.

Medical historians came from universities across the south.

And most movingly, several elderly nurses attended.

Men and women who had been trained in black hospitals in the 1940s and 1950s, some of whom remembered hearing about the old methods that Daniel Hayes had taught.

One of these nurses, a 92-year-old man named Thomas Jefferson, approached Sarah during the reception.

He walked slowly with a cane, but his eyes were bright with interest as he studied the photograph.

My nursing instructor at Mihairi Medical College in Nashville, he said, his voice thin but clear.

Talked about a nurse named Hayes, who had worked at Frederick Douglas Hospital in Philadelphia and then at several hospitals in the South.

He said this Hayes fellow knew things that the textbooks didn’t teach.

Old ways of diagnosing illness just by looking and touching, ways of treating infections before antibiotics were available.

We all thought he was just an old man.

But I learned some of those techniques from him and they saved lives.

Sarah felt her throat tightened.

That was Daniel Hayes, the boy in this photograph.

Thomas studied Daniel’s young face.

He passed something important down then.

That’s good.

That’s real good.

The exhibition ran for 6 months and attracted over 20,000 visitors.

It was reviewed in medical journals, history publications, and mainstream media.

The photograph was reproduced in textbooks about African-American history and medical history.

But perhaps the most meaningful response came from Beverly Patterson, Daniel’s descendant in Philadelphia, who had provided the crucial family letters.

She attended the exhibition with her daughter and granddaughter.

Three generations standing before the photograph of Clara and Daniel.

I never knew the full story.

Beverly said to Sarah, “My grandmother told me Uncle Daniel had wanted to be a doctor but couldn’t because of prejudice.

” And that was sad enough.

But knowing now what his mother did, what his grandmother did before her.

Knowing that they created this legacy of healing despite everything trying to stop them, that’s powerful.

That changes how I see my own family, my own history.

Sarah and James published their findings in the Journal of American Medical History.

The article titled Evidence in the Hands: A Three Generation Legacy of Black Medical Practice, 1860 to 1956, won several awards and sparked a broader conversation about undocumented medical practitioners in African-American communities throughout the South.

Other researchers began looking for similar stories, photographs, and documents that might reveal other hidden histories of black doctors, nurses, midwives, and healers who practiced outside the formal medical establishment because that establishment had excluded them.

The photograph itself took on a life beyond the exhibition.

Medical schools began using it in classes about medical history and health equity.

One physician wrote an essay about how the image had changed his understanding of medical expertise.

We think of credentials as proof of knowledge, but Clara Hayes’s hands are proof that knowledge and skill can exist outside of formal institutions, passed down through generations, preserved despite systematic attempts to erase it.

Uh, on the final day of the exhibition, Sarah stood alone in the gallery after hours, looking at the photograph one last time before it was packed up to travel to its next venue.

She had spent 6 months with this image, but she still found new details every time she looked at it.

The way the light caught the fabric of Clara’s dress, the barely visible mark on the studio floor, the determined set of Daniel’s jaw, but always her eyes returned to their hands.

Clara’s hands weathered and strong, marked by years of healing work.

Daniel’s younger hands already beginning to show the signs of the legacy he was inheriting.

You wanted someone to see, Sarah whispered to the silent photograph.

You wanted someone to know that you existed, that your work mattered, that your knowledge was real.

And now, 123 years later, we do.

We see you.

We know.

Uh, the photograph remained impassive.

Clara and Daniel forever frozen in that moment in 1895.

Their hands prominently displayed for anyone who cared to look closely enough.

But Sarah knew that what those hands represented, the knowledge, the dedication, the resistance against eraser was anything but frozen.

It lived on in every person who learned their story, in every medical student who now understood that expertise could exist outside traditional institutions, and every descendant who discovered that their ancestors had been healers and teachers and preservers of life-saving knowledge.

Clara Hayes had been right to commission that photograph.

She had been right to position their hands where they could be seen.

Because in the end, the evidence in those hands had testified to a truth that no amount of prejudice or institutional gatekeeping could erase.

That healing was not the exclusive domain of those with formal credentials.

That knowledge could be passed down through generations, even when official channels were closed, and that the work of saving lives transcended the boundaries that society tried to impose.

The photograph had seemed at first like just another portrait from 1895.

But once Sarah and James had looked closer, once they had truly seen what Clara and Daniel were showing them, it became something far more powerful, a testament to resilience, a documentary of resistance, and a bridge connecting past and present in the story of black medical practice in America.

As Sarah turned off the gallery lights and locked the door behind her, she knew that Clara and Daniel’s story would continue spreading, reaching people who needed to hear it, inspiring researchers to look for other hidden histories, and reminding everyone that sometimes the most important truths are right there in front of us, waiting for someone to look close enough to see

News

🌲 IDAHO WOODS HORROR: COUPLE VANISHES DURING SOLO TRIP — TWO YEARS LATER FOUND BURIED UNDER TREE MARKED “X,” SHOCKING AUTHORITIES AND LOCALS ALIKE ⚡ What started as a quiet getaway turned into a terrifying mystery, as search parties scoured mountains and rivers with no trace, until hikers stumbled on a single tree bearing a carved X — and beneath it, a discovery so chilling it left investigators frozen in disbelief 👇

In August 2016, a pair of hikers, Amanda Ray, a biology teacher, and Jack Morris, a civil engineer, went hiking…

⛰️ NIGHTMARE IN THE SUPERSTITIONS: SISTERS VANISH WITHOUT A TRACE — THREE YEARS LATER THEIR BODIES ARE FOUND LOCKED IN BARRELS, SHOCKING AN ENTIRE COMMUNITY 😨 What began as a family hike into Arizona’s notorious mountains turned into a decade-long mystery, until a hiker stumbled upon barrels hidden in a remote canyon, revealing a scene so chilling it left authorities and locals gasping and whispering about the evil that had been hiding in plain sight 👇

In August of 2010, when the heat was so hot that the air above the sand shivered like coals, two…

⚰️ OREGON HORROR: COUPLE VANISHES WITHOUT A TRACE — 8 MONTHS LATER THEY’RE DISCOVERED IN A DOUBLE COFFIN, SHOCKING AN ENTIRE TOWN 🌲 What began as a quiet evening stroll turned into a months-long nightmare of missing posters and frantic searches, until a hiker stumbled upon a hidden grave and police realized the truth was far darker than anyone dared imagine, leaving locals whispering about secrets buried in the woods 👇

On September 12th, 2015, 31-year-old forest engineer Bert Holloway and his 29-year-old fiance, social worker Tessa Morgan, set out on…

🌲 NIGHTMARE IN THE APPALACHIANS: TWO FRIENDS VANISH DURING HIKE — ONE FOUND TRAPPED IN A CAGE, THE OTHER DISAPPEARS WITHOUT A TRACE, LEAVING INVESTIGATORS REELING 🕯️ What started as an ordinary trek through the misty mountains spiraled into terror when search teams stumbled upon one friend locked in a rusted cage, barely alive, while the other had vanished as if the earth had swallowed him, turning quiet trails into a real-life horror story nobody could forget 👇

On May 15th, two friends went on a hike in the picturesque Appalachian Mountains in 2018. They planned a short…

📚 CLASSROOM TO COLD CASE: COLORADO TEACHER VANISHES AFTER SCHOOL — ONE YEAR LATER SHE WALKS INTO A POLICE STATION ALONE WITH A STORY THAT LEFT OFFICERS STUNNED 😨 What started as an ordinary dismissal bell spiraled into candlelight vigils and fading posters, until the station doors creaked open and there she stood like a ghost from last year’s headlines, pale, trembling, and ready to tell a truth so unsettling it froze the entire room 👇

On September 15th, 2017, at 7:00 in the morning, 28-year-old teacher Elena Vance locked the door of her home in…

🌵 DESERT VANISHING ACT: AN ARIZONA GIRL DISAPPEARS INTO THE HEAT HAZE — SEVEN MONTHS LATER SHE SUDDENLY REAPPEARS AT THE MEXICAN BORDER WITH A STORY THAT LEFT AGENTS STUNNED 🚨 What began as an ordinary afternoon spiraled into flyers, helicopters, and sleepless nights, until border officers spotted a lone figure emerging from the dust like a mirage, thinner, quieter, and carrying answers so strange they turned a missing-person case into a full-blown mystery thriller 👇

On November 15th, 2023, 23-year-old Amanda Wilson disappeared in Echo Canyon. And for 7 months, her fate remained a dark…

End of content

No more pages to load