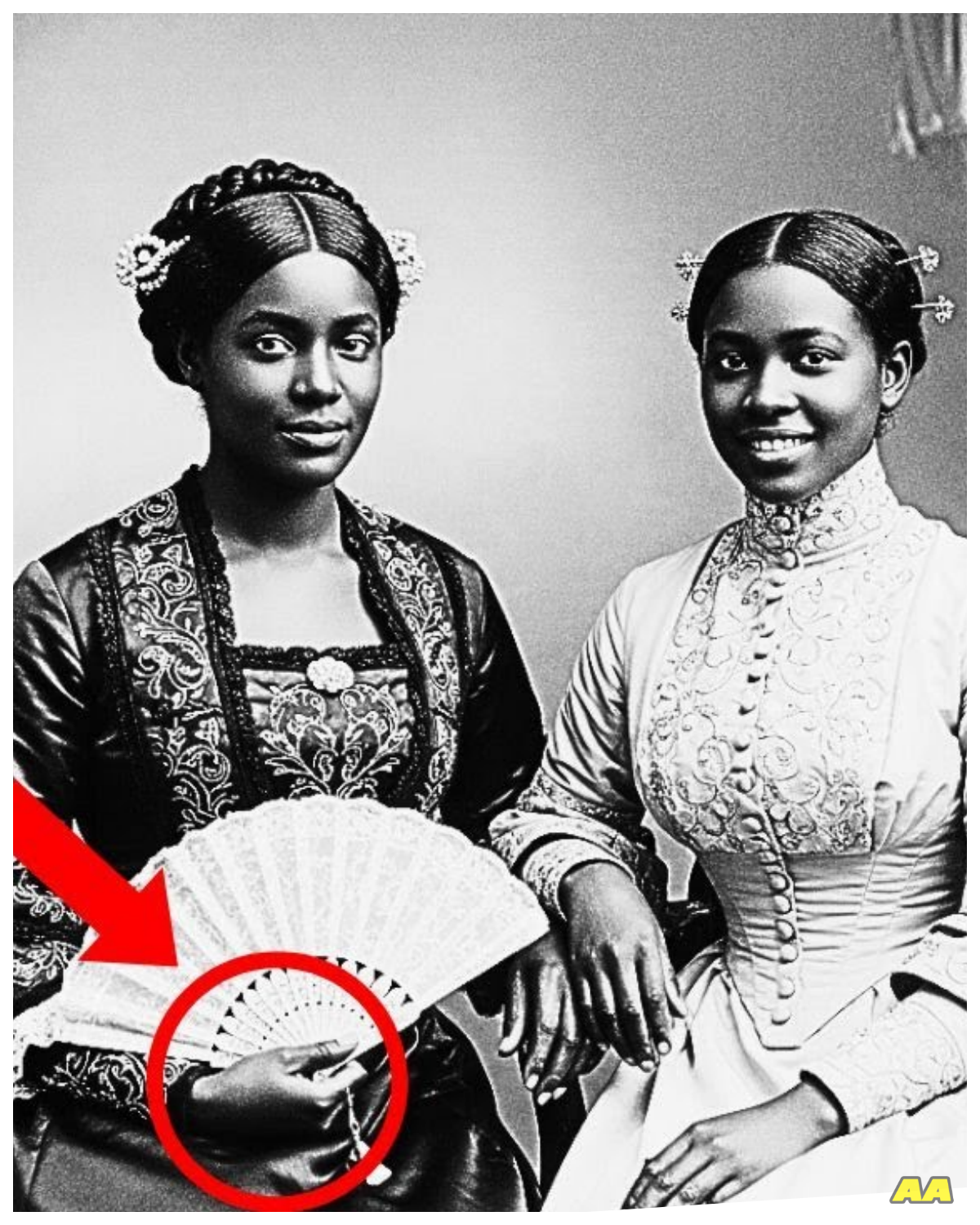

It was just a photo of two sisters, but it hid a dark secret.

The photograph appeared ordinary at first glance.

Sarah Miller, a digital archivist at the New Orleans Historical Society, had processed hundreds of 19th century portraits during her three years at the institution.

This one, dated 1891 and labeled simply studio portrait, unidentified subjects, showed two elegant black women seated in a professional photographer’s studio.

It was a Tuesday morning in February 2024 and Sarah was digitizing materials from a recently donated private collection.

The estate of a deceased photography collector had bequeathed over 2,000 images spanning 1850 to 1920.

And Sarah’s task was to scan, catalog, and research each one.

She placed the photograph carefully on the high resolution scanner.

The image showed two sisters, that much was evident from their striking resemblance, seated side by side against a painted backdrop of classical columns and draped fabric, typical of studio photography in the late 19th century.

The older sister, appearing to be in her late 20s, sat on the left in an elaborate dark dress with intricate beading along the bodice and sleeves.

Her posture was impeccable, shoulders back, chin slightly raised.

She held a decorative fan in her right hand, the ivory and lace accessory positioned elegantly across her lap.

Her expression was serene, composed with a hint of a subtle smile.

The younger sister, perhaps 25, sat slightly closer to the camera.

She wore an equally expensive gown in a lighter fabric with elaborate embroidery at the collar and cuffs.

Her hands rested empty in her lap, fingers interlaced.

She smiled more openly than her sister, her eyes engaging directly with the camera lens with an almost defiant confidence.

Both women were strikingly beautiful, their hair styled in the fashionable, upswept manner of the early 1890s, adorned with small decorative combs.

Their clothing spoke of wealth and status.

These were not servants dresses or simple cotton garments, but fine silk and velvet, the kind worn by women of means.

Sarah initiated the scan and watched as the machine’s light passed slowly across the photograph, capturing every detail in ultra high resolution.

Something about this image intrigued her.

Black women photographed in such obvious prosperity during this period were relatively rare in archival collections.

The scan completed and Sarah opened the digital file on her computer.

She zoomed in slowly, examining the studio backdrop, the furniture, the women’s clothing and jewelry.

Then her eyes settled on their hands and her breath caught in her throat.

Sarah leaned closer to her monitor, adjusting the brightness and contrast of the digitized image.

Modern scanning technology could reveal details invisible to the naked eye in original photographs, and what she was seeing made her stomach tighten with unease.

The older sister’s left hand, the one not holding the fan, rested in her lap.

At first glance, it appeared normal, but magnified.

The truth was horrifying.

At least three fingers bent at unnatural angles, clearly broken and healed incorrectly.

The knuckles were swollen and misshapen, the kind of deformity that came from repeated severe trauma.

The pinky finger curved inward at an impossible angle, permanently frozen in a position that suggested it had been shattered and never properly set.

Sarah’s hands trembled slightly as she shifted focus to the younger sister’s hands.

They were interlaced in her lap in what seemed like a demure ladylike pose.

But when Sarah increased the magnification, she saw the dark circular marks around both wrists, deep scarring that formed complete rings, the unmistakable signature of prolonged restraint by shackles or rope.

The scars were old but prominent, the kind that never fully faded, that marked the skin permanently.

She zoomed out and examined their faces more carefully.

Now that she knew to look for signs of trauma, she saw more.

The older sister had a small scar above her left eyebrow, barely visible, but there.

The younger sister’s left earlobe appeared slightly torn, as if an earring had been violently ripped out at some point.

But what disturbed Sarah most was the contradiction these details created.

These women sat in expensive silk dresses that would have cost more than most people earned in months.

They posed in a professional photography studio which charged premium rates.

They smiled with confidence and poise.

Yet their bodies carried unmistakable evidence of brutal sustained violence.

Sarah sat back in her chair, her mind racing through possibilities.

The post civil war south was a complicated, often brutal place for black Americans.

Slavery had ended officially in 1865, but systems of oppression had immediately replaced it.

Convict leasing, debt penage, sharecropping arrangements that functioned as bondage.

Black women were especially vulnerable to exploitation and violence.

But this photograph suggested something more complex than simple victimhood.

These sisters had somehow acquired significant money.

They had chosen to document themselves in this specific way.

Formally dressed, professionally photographed, young duai preserved.

There was intentionality here, a purpose, something Sarah couldn’t yet understand.

She checked the donation records again.

The photograph had come from the estate of Howard Clemens, a photography collector who had died at 93.

His collection note simply read, “Purchased at estate sale, New Orleans, 1978.

Origin unknown.

” Sarah made a decision.

This photograph deserved investigation.

Whatever story these two sisters carried needed to be uncovered.

She created a dedicated research folder, saved the highresolution scan, and began what would become the most consuming investigation of her career.

Sarah spent the next week unable to focus on anything except the photograph.

She contacted Dr.

Marcus Tibido, a retired professor of Louisiana history who specialized in 19th century photography.

She emailed him the image, asking if he could identify the studio based on the backdrop and furniture style.

His response came within hours.

The backdrop and furniture are consistent with the Devo studio on Royal Street, which operated from 1885 to 1897.

Jean Batist Devo was one of the few photographers in New Orleans who regularly accepted black clients, though his services were expensive, far beyond what most black families could afford.

This information deepened the mystery.

How did two black women with visible signs of severe abuse afford such an expensive portrait session? Sarah submitted a research request to the New Orleans Public Library for any surviving Devo studio records.

The library responded a week later.

The studio ledgers had survived, though incompletely, covering 1888 to 1895.

Sarah drove to the library immediately, her anticipation building.

The ledgers were bound in cracked leather, the pages yellowed and fragile.

She handled them with archival gloves, turning each page carefully, scanning entries for black female clients in 1891.

Most entries were straightforward.

Names, dates, portrait types, payments.

Then, on a page dated August 15th, 1891, she found it.

Two negro women, sisters, full portrait sitting, payment in advance, cash $12, no names provided per client’s request.

Subjects insisted on formal attire, broadown garments.

Photographer noted, “Subjects were unusually composed and specific about positioning and framing.

$12 was an enormous sum in 1891, equivalent to several weeks wages for most workers.

The sisters had paid in cash, insisted on anonymity, brought expensive clothing, and directed their own portrait session.

Everything about this suggested planning, resources, and purpose.

Sarah photographed the ledger page with her phone and continued searching.

She found no other entries matching this description.

No follow-up appointments, nothing to indicate the sisters had ever returned.

She turned her attention to hospital records.

Next, injuries as severe as those visible in the photograph would likely have required medical attention.

She began searching through digitized records from Charity Hospital, which treated black patients in the 1880s and 1890s.

The records were fragmentaryary and frustratingly vague.

Black patients were often recorded by first name only with minimal detail.

But Sarah persisted reading through hundreds of admission logs.

On her fourth day, she found something.

A ledger from April 1889 contained this entry.

Negro woman approximately 23 years.

Severe injuries to left hand, multiple fractures.

Appears deliberately inflicted.

Patient refused to provide name or circumstances.

Treatment provided.

Patient left against medical advice.

2 months later, June 1889.

Negro woman.

Approximately 21 years.

Deep lacerations and scarring around both wrists consistent with prolonged restraint.

Patient extremely reticent.

Wounds cleaned and dressed.

The ages matched.

The injuries matched.

The timeline was right.

Sarah felt certainty growing.

These hospital records documented the same women.

2 years before the photograph was taken.

Sarah expanded her search, looking for patterns in the hospital records.

What she discovered disturbed her profoundly.

Between 1885 and 1892, Charity Hospital treated at least 17 black women between ages 15 and 30 with injuries doctors described as deliberately inflicted or consistent with punishment.

The injuries followed patterns: broken fingers and hands, burn scars, deep lacerations on backs, and most commonly scarring around wrists and ankles from prolonged restraint.

None of these women had provided full names.

Most left against medical advice, often within hours of treatment.

Sarah cross- referenced this with historical context she knew from her academic training.

The period from 1877 to 1900 was dark in Louisiana history.

Reconstruction had ended.

Federal troops had withdrawn and white supremacist Democrats had regained control.

Black Americans found themselves systematically reubjugated through violence, discriminatory laws, and ponage debt bondage that functioned identically to slavery.

She began searching for documented penage cases in Louisiana during this period.

She found congressional testimonies from the early 1900s, newspaper articles from northern publications, court records of rare prosecutions.

One case caught her attention.

In 1893, federal agents investigated a wealthy New Orleans family named Lvini.

The family owned a sugar plantation up river and a townhouse in the French Quarter.

Anonymous tips led investigators to discover the Lavines were holding multiple black workers in conditions of bondage.

The investigation documented horrific abuses.

workers locked in rooms at night, beaten for minor infractions, branded to prevent escape, worked without compensation for years.

The Lavines claimed everything was legal, that these were voluntary contracts.

The case went to trial.

Despite overwhelming evidence, the Lavines were acquitted.

The all-white jury deliberated less than an hour, but what made Sarah’s blood run cold was a detail in the trial transcript.

One escaped worker who testified was a young black woman named Clara.

She described being held by the Lavines from age 14 to 23 along with her younger sister.

She described having her fingers deliberately broken with a hammer for stealing food scraps.

She described being shackled at night.

The transcript noted Clara’s testimony was difficult to verify due to her obvious physical impairment.

The defense attorney pointed to her mangled left hand as evidence she was unreliable.

Clara’s sister wasn’t mentioned as having testified.

No other record of her appeared.

Sarah searched for what happened to Clara after the trial and found nothing.

No census records, no death certificate.

Clara had vanished from history.

The timeline matched, the injuries matched, the ages matched.

Sarah felt certainty crystallizing.

The sisters in the photograph could be Clara and her unnamed sister, photographed in August 1891, 2 years before the trial.

But why would they spend precious money on a formal portrait after escaping? Why smile? Why present themselves with such deliberate elegance? Sarah stared at the photograph and suddenly understood, “This wasn’t a portrait of victims.

This was a statement, a defiant declaration.

We survived.

We will not be erased.

” But there was something else.

Something darker Sarah couldn’t yet articulate.

Something about the timing suggested more than survival.

Sarah’s next step was researching the Lavine family thoroughly.

The Louisiana State Archives held extensive records on prominent families, and the Lavines were certainly prominent.

They had been sugar plantation owners since before the Civil War, had owned over 200 enslaved people, and emerged from the war with wealth intact.

The family patriarch during the 1880s and 1890s was August Levvenia, born in 1831, who had inherited the plantation and New Orleans townhouse from his father.

He had married Margarite Tibo in 1855.

They had three children, Henri, Louie, and Celeste.

Sarah found property records, tax documents, and social notices in old newspapers.

The Lavines were described as pillars of the community, generous benefactors, exemplars of southern grace.

August served on charitable boards.

Margarite was noted for elegant parties and arts patronage.

Reading these descriptions while knowing what the family had actually done, holding people in bondage, torturing them made Sarah feel physically ill.

This was how power protected itself, she thought.

Through respectability, through social status, she searched for death records, curious when August and Margarite had died.

What she found shocked her completely.

August Lavine died September 3rd, 1891, less than 3 weeks after the photograph was taken.

Cause of death: acute poisoning.

Cause undetermined.

He was 60.

Margarite Lavine died September 7th, 1891, 4 days after her husband.

Cause of death, sudden illness, complications from poisoning.

She was 57.

Sarah sat motionless, staring at the screen.

Both dead within 4 days, both from poisoning, both within weeks of the photograph.

This could not be coincidence.

The Times Pikyune had covered the story extensively.

Articles described the deaths as tragic and mysterious.

August had fallen ill after dinner on September 2nd, suffering severe abdominal pain, vomiting, and convulsions.

He died the following morning.

Margarite, who nursed him during his final hours, began showing identical symptoms on September 5th and died 2 days later.

The family physician, Dr.

Edmund Russo, stated the symptoms were consistent with poisoning, possibly from contaminated food or accidental exposure.

Police investigated briefly, but found no evidence of foul play.

The conclusion, accidental poisoning, perhaps through spoiled food.

The funeral was one of the largest New Orleans had seen.

Hundreds attended.

Eulogies praised Augusta’s business acumen and Margarit’s charitable works.

No mention of the federal investigation that would come two years later.

Sarah pulled up the photograph again, zooming in on the sisters faces.

They had posed mid August 1891.

August and Margarite Lavine died early September 1891.

The sisters smiled with a confidence that now seemed to carry entirely different meaning.

She returned to Clara’s 1893 trial testimony.

Reading more carefully, Clara described the Lavine townhouse layout in detail.

Rooms where workers were held, the kitchen where they prepared family meals, locked doors, and barred windows.

Clara and her sister had been assigned to kitchen work primarily.

They prepared the family’s meals under supervision, but they handled the food, cooked it, plated it, access to the food, access to the family’s meals, an opportunity.

Sarah needed to trace what happened to the sisters after the Lavine’s deaths.

She returned to the 1893 trial transcript, searching for any detail about Clara’s background that might help locate her and other records.

Clara had mentioned during testimony that she and her sister had been born in St.

Landry Parish, north of New Orleans.

Their mother had been enslaved on a plantation there before the war.

After emancipation, she stayed in the area working as a laress until she died in 1883.

That’s when Clara, then 14, and her sister, then 12, had been taken by the Levines.

The transcript said they were claimed as wards after their mother’s death, a common practice where white families asserted legal guardianship over black children, then forced them into unpaid labor.

Sarah searched St.

Landry Parish records from the 1880s.

She found a death certificate for a woman named Rose, listed as Negroundress, died March 1883, age approximately 38.

Cause of death, consumption, tuberculosis.

The record noted she left two minor daughters, but listed no names.

Sarah then searched for any guardianship records from 1883 involving the Lavine family.

She found it, a document dated April 1883, stating that August Lavine had assumed guardianship of two negro orphans, female, ages approximately 12 and 14, from St.

Landry Parish.

The document claimed this was an act of charity, providing the children with shelter, sustenance, and moral instruction in exchange for light household duties.

The language was benevolent.

The reality was bondage.

These girls had been trapped for 8 years from 1883 to 1891.

Subjected to violence and exploitation with no legal recourse, but they had escaped.

Somehow between the Lavine’s death in September 1891 and Clara’s testimony in 1893, the sisters had gotten free.

And 3 weeks before those deaths, they had sat for an expensive formal portrait dressed in silk, smiling.

Sarah searched for any police reports or investigations from September 1891 related to the Lavine household.

She found nothing about missing workers or escaped servants.

The Lavine children, Henri, Louie, and Celeste, all adults by then, had apparently not reported anyone missing.

Perhaps they hadn’t realized the sisters were gone until after the funerals.

Perhaps they had been too consumed with grief and shock.

Or perhaps they had suspected something and chosen to remain silent, unwilling to draw attention to their family’s illegal activities.

Sarah found one more crucial document, a property inventory from the Lavine estate, dated October 1891, 1 month after both deaths.

The townhouse was being prepared for sale.

The inventory listed furniture, artwork, silverware, linens, every item of value.

At the bottom of the list, almost as an afterthought.

Note, household staff departed without notice following Madame Lavine’s passing, unable to recover wages owed or obtained forwarding information.

Household staff, not wards, not servants, just a bureaucratic note about departed workers, as if they had simply quit rather than escaped from bondage.

No investigation, no search, just a notation in an estate document.

The sisters had vanished completely, and Sarah suspected they had done so deliberately, carefully, leaving no trail that could lead back to them.

She stared at the photograph again.

This portrait wasn’t just documentation or defiance.

This was insurance.

This was evidence.

If anyone ever questioned what had happened to August and Margarite Lavine, if anyone ever traced the deaths back to two escaped black women, this photograph would testify to their suffering, would show their broken hands and scarred wrists, would demonstrate exactly why they might have wanted revenge.

Sarah needed to understand how the Lavines had been poisoned.

The newspaper accounts had been vague, mentioning only acute poisoning and contaminated food.

She searched for more detailed medical records from September 1891.

Dr.

Edmund Rouso, the Lavine family physician, had written a report for the coroner.

Sarah found it archived with the Orleans Parish death records.

The report described August’s symptoms in clinical detail.

severe gastric distress, violent vomiting, intense abdominal cramping, convulsions, rapid pulse, dilated pupils, followed by circulatory collapse, and death approximately 14 hours after symptom onset.

Margarit’s symptoms had been identical, though her death took slightly longer, approximately 36 hours from onset to death.

Dr.

Russo had noted symptoms consistent with ingestion of toxic alkyoid, possibly from plant source.

Could be accidental consumption of poisonous vegetation or deliberate administration.

No definitive determination possible without chemical analysis of stomach contents which family declined.

Sarah researched toxic alkyoids available in Louisiana in 1891.

Several plants fit the symptom profile.

Oleander, gyson, bleedana.

All grew wild in Louisiana.

All could be processed into lethal poisons by someone with knowledge.

But the most likely candidate was something even more accessible.

Arsenic.

Arsenic was widely available in 1891.

Sold openly inarmacies and general stores as rat poison, insecticide, and even as a medicine.

It was cheap, easy to obtain, and its symptoms matched what Dr.

Rouso had described.

Small doses of arsenic administered over time would accumulate in the body, causing chronic illness.

A larger acute dose would cause exactly what August experienced.

Violent gastric symptoms, convulsions, death within hours, and arsenic could be easily hidden in food.

It was tasteless in small amounts, especially when mixed into strongly flavored dishes.

Sarah thought about Clara’s testimony.

She and her sister had prepared the Lavine family’s meals.

They had access to the kitchen, to the food, to opportunities to add something that wouldn’t be noticed until too late.

But proving this 133 years later was impossible.

There were no forensic records detailed enough.

No surviving physical evidence, no witnesses.

What Sarah could establish was motive, means, and opportunity.

The sisters had motive.

8 years of brutal captivity and torture.

They had means, access to poison, and to the family’s food.

They had opportunity.

unsupervised time in the kitchen preparing meals, and they had escaped immediately after, vanishing so completely that even the Lavine children couldn’t locate them.

Sarah found one more piece of evidence.

In a letter written by Celeste Lavine to her brother, Henri in October 1891, preserved in the family papers, Celeste wrote, “I cannot stop thinking about father and mother’s final days.

The doctor says it was likely spoiled meat or contaminated water, but I have my doubts.

The household girls disappeared so quickly after mother’s funeral.

Perhaps they knew something.

Perhaps they feared illness themselves.

Or perhaps, but I cannot write such thoughts.

They are too horrible to contemplate.

Celeste had suspected, but she had chosen not to pursue those suspicions.

Perhaps out of fear of scandal, perhaps out of unwillingness to confront her family’s crimes.

The photograph on Sarah’s screen seemed to glow with new significance.

Two sisters dressed in silk, holding themselves with quiet dignity, smiling with knowledge of what they had done and survived.

This wasn’t just a portrait.

This was a victory photograph.

Sarah had been thinking of the sisters as Clara and her unnamed sister for weeks.

But Clara was a name given in testimony, possibly not even accurate.

Sarah wanted to know their real names, the names their mother had given them, the names they called each other, she returned to St.

Landry Parish records.

Searching more carefully around 1883 when their mother Rose had died.

She found church records from a small Baptist congregation that served the black community.

Rose’s death was noted in the church ledger and beside it written in faded ink.

Sister Rose departed this life March 14th, 1883.

Leaves behind daughters, Clara, 14, and Grace, 12.

May the Lord watch over these orphaned lambs, Clara and Grace.

Finally, they had names.

Sarah searched for any record of Clara and Grace after 1891.

She checked census records from 1900, 1910, and 1920.

She searched marriage records, death certificates, land ownership documents.

She found nothing under those names in Louisiana.

They had likely changed their names.

She realized after what they had done, whether murder or justified vengeance, they would have needed to disappear completely to become other people.

Sarah tried a different approach.

She searched for black women who appeared suddenly in census records in the 1890s with no prior documentation.

Women whose ages would match Clara and Graces.

It was like searching for ghosts.

There were thousands of possibilities.

And without photographs to compare, no way to confirm identities.

Then Sarah remembered something.

The photograph showed not just their injuries, but their appearance, their features.

She had access to facial recognition technology through the historical society’s digital archive system.

It was imperfect with old photographs, but sometimes it could find matches.

She uploaded the sister’s portrait and ran it against the society’s collection of over 50,000 historical photographs from Louisiana and surrounding states.

The system would search for similar facial structures, accounting for age and image quality.

The search ran for hours.

Sarah went home that evening not expecting results.

But when she checked the next morning, the system had flagged three potential matches.

The first two were clearly false positives.

The facial structures were only superficially similar, but the third made Sarah’s heart race.

It was a photograph from 1897, 6 years after the sister’s portrait.

The image showed a group of women at a church gathering in Mobile, Alabama.

The photograph was labeled First Baptist Church Ladies Aid Society.

And in the back row, standing slightly apart from the others, were two black women whose faces matched Clara and Grace with high probability according to the system.

The caption listed names for everyone in the photograph.

The two women in question were identified as Mrs.

Clara Freeman and Mrs.

Grace Freeman.

Freeman, the same surname.

Sisters who had escaped together, started new lives together, taken a new family name together.

Sarah searched mobile records for Clara and Grace Freeman.

She found them in the 1900 census.

Clara Freeman, age 32, listed as widow, occupation seamstress.

Grace Freeman, age 30, listed as widow, occupation laress.

They lived together in a small house on Davis Avenue.

The 1910 census listed them at the same address, still living together, both still working.

Both still listed as widows, though Sarah suspected neither had ever married.

The widow designation was simply more respectable than spinster and raised fewer questions.

She found one more record.

A death certificate for Grace Freeman died 1918, age 48, caused influenza during the great pandemic.

Clara Freeman was listed as next of kin.

And finally, a death certificate for Clara Freeman died 1924, aged 56 because heart failure.

No next of kin listed.

They had lived quiet lives in Mobile, working honestly, attending church, harming no one.

They had survived their captivity, enacted their revenge, and built new lives far from New Orleans.

And they had taken the secret of what they had done to their graves.

Sarah sat in her office at the historical society, surrounded by months of research, looking at the photograph that had started everything.

She finally understood the full story, or as much of it as could be recovered across 133 years.

Clara and Grace, daughters of Rose born into freedom after the Civil War, but orphaned young, claimed as wards by the Lavine family, trapped in bondage, disguised as guardianship.

Eight years of brutal labor, violence, torture, fingers broken as punishment, wrists scarred from shackles, bodies marked by a family’s cruelty.

But Clara and Grace had survived.

They had planned, waited, gathered resources.

Somehow they had acquired or stolen money, perhaps small amounts taken over years from the Lavine household.

They had purchased expensive dresses, possibly secondhand from a pawn shop or sympathetic merchant.

They had saved $12 for a portrait session.

In mid- August 1891, they had posed for their photograph, a declaration of their humanity, their dignity, their defiance.

They smiled, not as victims, but as women who had already decided what would come next.

Weeks later, they had poisoned August and Margarite Lavine.

Whether using arsenic or another poison, they had administered it through the family’s food, using the access their kitchen duties provided.

They had watched August die in agony, watched Margarite follow days later, and then they had vanished, leaving New Orleans for Mobile, Alabama, taking new names, building new lives.

They had lived for decades as Clara and Grace Freeman, ordinary working women, respected church members.

Their past buried completely.

The photograph remained as evidence of what had been done to them.

justification for what they had done in return.

Sarah wondered if the sisters had kept a copy themselves or if the photographers’s archive copy was the only one that survived.

Sarah knew she had to publish this research.

It was an important historical story about ponage, about the violence black Americans faced in the post reconstruction south, about resistance and survival, but how to tell it? Should she explicitly state that Clara and Grace had murdered the Lavines? Or should she present the evidence and let readers draw their own conclusions? She thought about the moral complexity of the story.

By any legal definition, what Clara and Grace had done was murder.

But morally, after eight years of torture, after being held illegally, after having no legal recourse in a system designed to oppress them, Sarah decided to present the facts honestly and completely, including the evidence that strongly suggested Clara and Grace had poisoned their captives.

But she would frame it within the historical context, explaining the system that had trapped them, the violence they endured, the impossibility of legal justice.

She would let their photograph speak for itself.

two beautiful, dignified women smiling despite everything that had been done to them, their broken hands, visible testimony to their suffering and their strength.

Sarah began writing the research paper that would eventually be published in the Journal of Southern History.

She titled it Captivity, Resistance, and Vengeance: The Untold Story of Clara and Grace in post reconstruction Louisiana.

The article would be controversial.

Some historians would question her conclusions.

Some would argue she was glorifying murder.

Others would praise her for recovering a lost story of black resistance.

But Sarah knew the story needed to be told.

Clara and Grace deserve to be remembered, not as anonymous victims, not as criminals, but as complex human beings who survived unimaginable circumstances and fought back the only way they could.

6 months after Sarah published her research, the photograph of Clara and Grace went viral online.

A historian with a large social media following had shared the image along with a summary of their story.

Within days, millions of people had seen it.

The responses were intense and varied.

Many people expressed outrage at what had been done to Clara and Grace, calling them heroes for fighting back.

Others debated the morality of their actions, arguing about whether murder could ever be justified.

Some questioned whether Sarah’s conclusions were accurate or speculative.

But what moved Sarah most were the messages from descendants of people who had been held in page systems across the South.

Dozens of people reached out, sharing family stories that had been passed down through generations.

stories of ancestors who had been trapped in debt bondage, subjected to violence, denied freedom even after slavery’s official end.

One woman, Linda Washington, from Atlanta, sent to Sarah a message with an attached photograph.

This is my great great grandmother, Ruth.

Linda wrote, “A family stories say she was held by a white family in Georgia in the 1890s, that she finally escaped when she was in her 20s.

She never talked about those years, but my grandmother said Ruth’s hands were scarred and deformed, that she had marks on her wrists from shackles.

” Your article about Clara and Grace made me realize my great great-grandmother’s story was part of a much larger pattern.

Thank you for bringing this history to light.

Sarah began collecting these stories, creating an online archive of penage, testimonies, and family histories.

The archive grew quickly, filled with painful accounts, but also stories of resistance, escape, and survival.

The New Orleans Historical Society created a permanent exhibition featuring Clara and Grace’s photograph along with Sarah’s research.

The exhibition included context about penage systems, primary documents from the Lavine case, and information about the broader history of black resistance in the postreonstruction south.

On the exhibition’s opening day, Sarah stood before the large reproduction of the photograph.

Clara and Grace looked out at the crowd, their elegant dresses and composed expressions unchanged across 133 years.

But now their story was known.

Now their names were remembered.

A young black woman approached Sarah after the opening remarks.

I’m a student at Tulain, she said.

I’m studying history because I want to recover stories like this.

Stories that have been buried or ignored.

This photograph, seeing their faces, knowing what they survived and what they did, it means everything to me.

It shows that our ancestors weren’t just victims.

They fought back.

Sarah nodded, moved by the woman’s words.

This was why the work mattered.

Not just to document the past, but to honor the people who had lived it, who had suffered and resisted and survived.

She looked again at Clara and Grace, at their slight smiles and their damaged hands, at the contradiction between their formal elegance and the violence their bodies had endured.

This photograph had hidden its secret for over a century, waiting for someone to look closely enough to care enough to piece together the fragments of a story that had been deliberately buried.

Clare and Grace had posed for this portrait, knowing what they were about to do, knowing they would soon disappear into new lives.

They had documented themselves at this precise moment after suffering before vengeance on the threshold between victimhood and agency.

The photographment was their testimony, their declaration, their revenge.

It had outlasted the Lavine family, outlasted the punish system, outlasted the deliberate amnesia that tried to erase such stories.

And now, finally, it was speaking.

Sarah thought about all the other photographs still sitting in archives and atticts, all the hidden details waiting to be noticed, all the stories waiting to be recovered.

Clara and Grace’s photograph had found its voice after 133 years.

How many others were still waiting? The work would continue.

The stories would be told.

The past would be confronted honestly in all its complexity and pain and resistance.

And the people who had been relegated to the background of history.

The scarred, the brutalized, the ones who fought back would finally be brought into the light and honored.

Clara and Grace smiled from their photograph, dignified and undefeated.

Their secret finally revealed.

Their story finally told.

News

🎬 JOE ROGAN STUNNED AS MEL GIBSON REVEALS THE PASSION OF THE CHRIST SECRETS NOBODY SAW COMING ⚡ What started as a casual podcast turns into an explosion of hidden truths as Gibson claims that decades of subtle symbolism, behind-the-scenes miracles, and shadowy warnings were deliberately left out of public view, leaving Rogan frozen, eyes wide, as the conversation twists faith, film, and scandal into one jaw-dropping revelation 👇

The Silent Echoes of Truth In the dimly lit room, Jim Caviezel sat alone, shadows dancing across the walls. The…

🎭 “I CARRIED THE CROSS OFF CAMERA TOO” — JIM CAVIEZEL FINALLY BREAKS HIS SILENCE ABOUT THE PASSION OF THE CHRIST AND REVEALS THE PAIN THAT NEVER STOPPED 🔥 In a trembling confession years after the cameras stopped rolling, Caviezel describes lightning strikes, broken bones, and eerie accidents that shadowed the set, hinting the suffering didn’t end with “cut,” but followed him home like a curse, leaving him wondering whether the role changed his soul forever 👇

The Silent Echoes of Truth In the dimly lit room, Jim Caviezel sat alone, shadows dancing across the walls. The…

🔥 “THEY DIDN’T WANT YOU TO READ IT” — MEL GIBSON CLAIMS THE ETHIOPIAN BIBLE WAS ‘BANNED’ AFTER CHURCH LEADERS DISCOVERED PASSAGES TOO POWERFUL TO CONTROL 📜 In a tense, late-night interview, Gibson alleges ancient texts hidden for centuries contain forbidden prophecies, missing books, and teachings that challenge everything modern Christianity was built on, warning that once believers see what was removed, “faith will never look the same again” 👇

The Forbidden Pages of Faith In the shadowy corridors of history, where whispers of the past linger like ghosts, Mel…

⚰️ MEL GIBSON STUNNED SILENT AS LAZARUS’ TOMB IS FINALLY OPENED — WHAT ARCHAEOLOGISTS FOUND INSIDE LEFT THE CREW TREMBLING 💥 Cameras roll as stone is moved for the first time in centuries, dust rising like smoke, and Gibson reportedly freezes mid-step, staring into the darkness as whispers spread that what lies inside doesn’t match anything historians expected, turning a biblical legend into a chilling, heart-pounding discovery that feels more like prophecy than history 👇

The Tomb of Secrets: A Hollywood Revelation The Unveiling of Lazarus: A Revelation That Shook the World In the heart…

🩸 JONATHAN ROUMIE & MEL GIBSON BREAK DOWN IN TEARS OVER THE SHROUD OF TURIN — HOLY RELIC SPARKS RAW CONFESSIONS AND SHOCKING REVELATIONS 💥 What began as a calm discussion turns into an emotional storm as the two stars speak with trembling voices about faith, doubt, and the weight of portraying Christ, their words hanging heavy in the air like incense, leaving viewers stunned as Hollywood meets holiness in a moment that feels less like an interview and more like a reckoning 👇

The Veil of Secrets In the dim light of a forgotten chapel, Jonathan Roumie stood before the ancient relic, the…

🩸 MEL GIBSON BLASTS THE VATICAN — “THEY’RE LYING TO YOU ABOUT THE SHROUD OF TURIN!” — HOLY RELIC ROW ERUPTS INTO GLOBAL FIRESTORM 🔥 Cameras barely start rolling before Gibson leans in, voice shaking with fury, claiming centuries of “carefully managed truth” and hinting that what believers were shown isn’t the whole story, sending historians scrambling, priests bristling, and millions wondering if the world’s most sacred cloth hides secrets too explosive for daylight 👇

The Shroud of Secrets Mel Gibson stood at the edge of a precipice, the weight of centuries pressing down on…

End of content

No more pages to load