It Was Just a Photo of a Happy Family — But the Child’s Position Revealed a Secret

It was just a photo of a happy family, but the child’s position revealed a secret.

The photograph arrived at the Philadelphia Historical Society in a worn leather portfolio, donated by an elderly woman clearing out her grandmother’s attic.

Among dozens of mundane documents and faded receipts, this single image stood out, not because it was remarkable, but because it was so perfectly ordinary.

Dr.Sarah Mitchell, a researcher specializing in post Civil War African-American history, barely glanced at it initially.

Another family portrait from 1868.

another somber group staring into the camera with the rigid formality that early photography demanded.

She’d seen hundreds like it, but something made her pause.

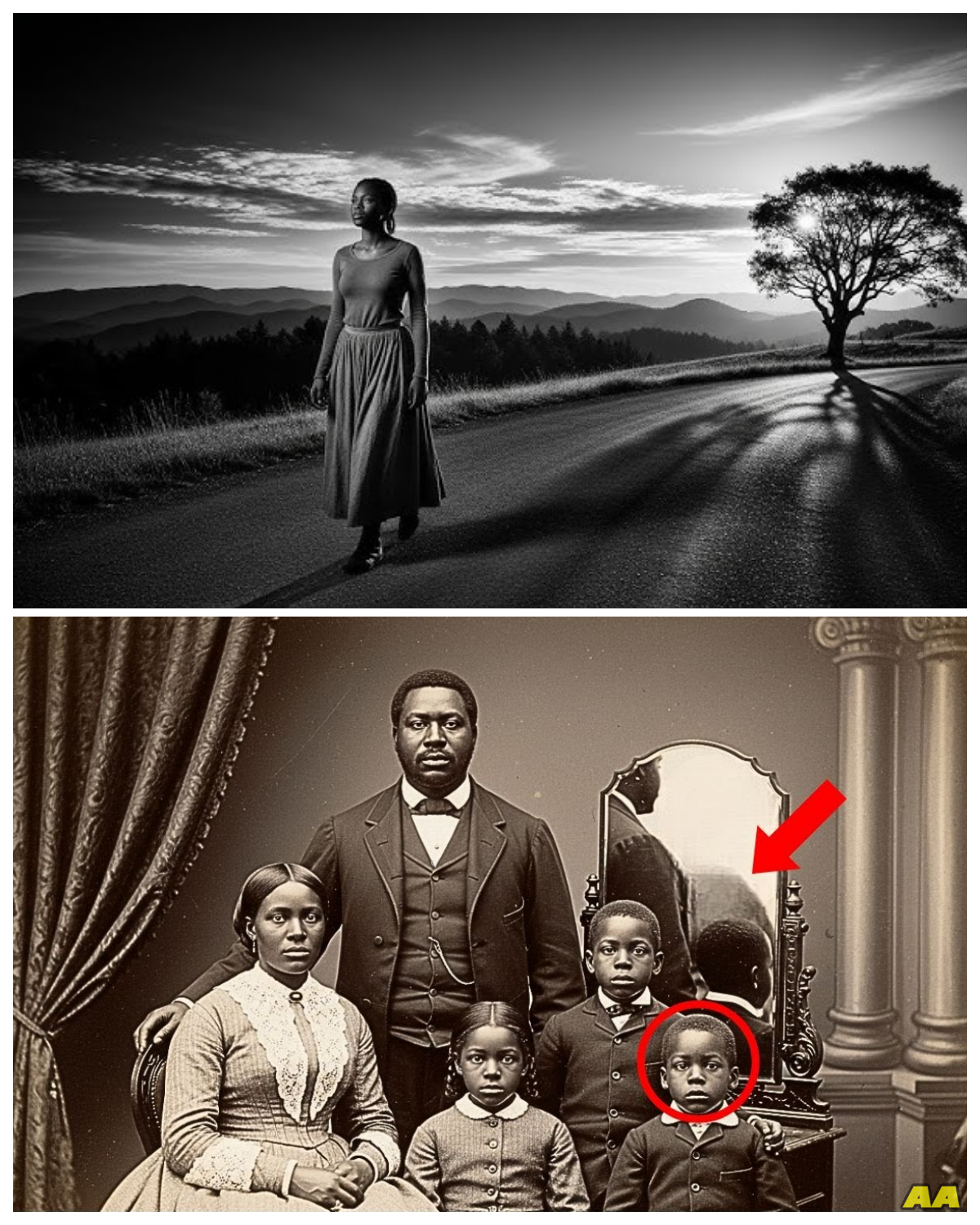

The family consisted of five people, a broad-shouldered man in a dark suit, his hand resting protectively on the shoulder of a woman in an elegant dress with delicate lace collar.

Three children stood before them, dressed in their Sunday best.

The backdrop was typical of a Philadelphia studio.

Painted columns, draped fabric, artificial grandeur meant to dignify the subjects.

Sarah pulled her magnifying glass closer, studying the faces.

The father’s expression carried quiet pride.

The mother’s eyes held a certain warmth despite the era’s photographic constraint against smiling.

The two older children, a boy and a girl perhaps 10 and 8, stared directly at the camera with that unblinking intensity Victorian photography required.

But the youngest child, a boy no more than six, was different.

His eyes weren’t looking at the camera at all.

They were fixed on something beyond the frame off to the right with an expression Sarah couldn’t quite identify.

Not fear, exactly.

Not curiosity either.

Something more deliberate, more knowing.

“That’s odd,” she whispered to the empty archive room.

She repositioned her lamp, angling the light across the photograph surface.

The image was remarkably well preserved, the chemicals having aged with minimal degradation.

The studio’s name was barely visible in the bottom corner.

Whitman and Sons Photography, Race Street, Philadelphia.

Sarah made a note to research the studio later, then returned her attention to the youngest boy.

Why would a child look away during such an important, expensive portrait? Families saved for months to afford studio photography.

Every detail mattered.

Parents coached their children for days about standing still, looking proper, representing the family with dignity.

Yet, this boy was looking somewhere else entirely.

She adjusted the magnifying glass again, moving slowly across the image.

The painted backdrop showed classical architecture, fake marble, fake refinement.

But behind the family, partially obscured by the draped fabric the studio used for atmosphere, something caught the light strangely.

Was that a mirror? Sarah’s breath caught.

In 1868, photographers sometimes use mirrors strategically to create depth or reflect light.

But this reflection seemed unintentional, accidental even, a strip of silvered glass partially visible behind the curtain, catching just enough light to create a ghostly, blurred image, an image of someone who wasn’t supposed to be there.

Her hands trembled slightly as she reached for her digital scanner.

This photograph, she suddenly realized, was hiding something, and that little boy with his carefully averted gaze might have been the only one brave enough or young enough to look directly at the truth.

Sarah spent the next morning tracking down the donation records.

The elderly woman who’ brought the portfolio was named Dorothy Peterson, and she’d left a phone number.

After three rings, a warm but tired voice answered, “Mrs.

Peterson, this is Dr.

Mitchell from the Historical Society.

I’m calling about the materials you donated last week.

” “Oh, yes, dear.

My grandmother’s things.

I hope they’re useful.

Most of it was just old papers.

Actually, there’s a photograph I’d like to ask you about.

A family portrait from 1868.

Do you know who these people were? There was a pause, then a soft intake of breath.

That would be my great great grandparents.

The Williams family, Thomas and Martha Williams, and their children.

Thomas Jr.

, Clara, and Little Samuel, Sarah wrote quickly.

Samuel was the youngest.

Yes, he was my great-grandfather.

Lived to be 93, sharp as attack until the very end.

Dorothy’s voice carried affection across the decades.

He used to tell the most wonderful stories about old Philadelphia.

Mrs.

Peterson, would you be willing to meet? I have some questions about the photograph, and I think there might be something historically significant here.

Another pause, longer this time.

When Dorothy spoke again, her voice had changed.

Quieter, more careful.

What did you find? I’m not entirely sure yet, but I think your great-grandfather might have witnessed something important, something that was deliberately hidden.

The silence stretched.

Sarah could hear traffic in the background, the distant sound of a television.

He told me once, Dorothy finally said that the photograph was taken on the most dangerous day of his life.

I was young, maybe 10, and I thought he was being dramatic.

Old people exaggerate, you know, but he was serious.

Said that picture proved his family were heroes, even though no one could ever know.

Sarah’s pulse quickened.

Did he explain what he meant? No.

He died 2 weeks later, and I never got the chance to ask.

Dorothy’s voice cracked slightly.

I’ve wondered about it my whole life.

That photograph sat in my grandmother’s drawer for 70 years, then in mine for another 30.

I brought it to you because I thought maybe someone could figure out what he meant.

They arranged to meet the following afternoon.

Sarah spent the rest of the day researching the Williams family through census records, city directories, and property documents.

Thomas Williams was listed as a blacksmith with a shop on South Street.

Martha Williams was recorded as a seamstress.

They owned their home.

Remarkable for a black family.

In 1868, just 3 years after the Civil War’s end, the children appeared in school records.

Thomas Junior and Clara attended the Institute for Colored Youth, one of the few schools that educated black children to a high standard.

Samuel, at six, was likely still at home.

But it was a newspaper clipping from July 1868 that made Sarah’s hand freeze over the archive table.

Local Negro family questioned in suspected harboring case.

No charges filed.

The article was brief, dismissive in the casually racist language of the era.

Authorities had investigated the Williams household following anonymous reports of suspicious activity, but found no evidence of wrongdoing.

The family maintained they were simply honest workers and the matter was dropped harboring in 1868.

The 13th Amendment had abolished slavery in 1865.

The war was over.

Freedom was law.

But Sarah knew what many didn’t.

The Underground Railroad hadn’t stopped with abolition.

Couldn’t stop.

Because in the South, in the isolated rural areas and under the cover of corrupt local governments, some people were still being held in slavery.

Illegal, hidden, but terrifyingly real.

and the networks that had helped people escape before the war, continued their work in secret, moving people from bondage to true freedom, usually toward Canada, where American law couldn’t reach them.

The Williams family, Sarah realized with growing certainty, had been part of that network.

And somehow, impossibly, they had documented it in a photograph.

The next morning, Sarah stood on Ray Street in Philadelphia’s historic district, staring up at the building that once housed Whitman and Sun’s photography.

It was now a cafe with exposed brick and industrial lighting, but the bones of the original structure remained.

Tall windows designed to capture natural light, high ceilings for portrait backdrops.

Inside, she ordered coffee and asked the young barista about the building’s history.

It’s been like six different businesses, he said clearly bored.

But yeah, it was a photography studio way back.

There’s some old stuff in the basement, the owner kept.

Historical preservation rules or whatever.

$20 and a charming smile got Sarah access to the basement.

The space was cramped, dusty, filled with restaurant supplies and broken furniture.

But in the far corner, behind stacks of chairs, she found three wooden crates marked with faded ink.

Whitman archives handled with care.

Her hands shook as she pried open the first crate.

Glass plate negatives, hundreds of them carefully wrapped in old newspaper, each one a frozen moment from the 1860s and 70s.

Studio portraits, mostly stiff families, serious merchants, children in elaborate clothing.

The visual record of Philadelphia’s middle class in the aftermath of war.

The second crate held ledgers, business records documenting every client, every sitting, every payment.

Sarah flipped through carefully, searching for 1868, July Williams.

There written in elegant script.

July 23rd, 1868.

Williams family, Thomas, Martha, children, full portrait sitting.

Payment 450, special arrangement, evening session.

Evening session, that was unusual.

The studios worked by natural light, scheduling sittings during daylight hours when the sun through those tall windows provided the illumination to garype and early photography required.

Why would the Williams family need an evening session? Sarah’s mind raced.

Evening meant darkness outside.

It meant the street would be empty, meant privacy.

She dug deeper into the ledger.

Most entries were straightforward.

Names, dates, payments.

But scattered throughout, perhaps once or twice a month, she found other evening sessions, different families, all with the same notation.

special arrangement.

All of them African-American families based on the surnames she recognized from her research.

Her coffee grew cold as she cross-referenced names with historical records.

The Patterson family, the father was listed in abolitionist society documents as a conductor.

The Morris family, their home had been searched twice by authorities looking for contraband in the years after the war.

The Hughes family, the mother, had testified in a freedom suit, helping prove that a woman was being held illegally in Maryland.

These weren’t random portrait sittings.

This was documentation, evidence, a visual record of the people who formed Philadelphia’s continuation of the Underground Railroad.

But why? Why risk creating permanent evidence of illegal activity? Sarah sat back on her heels, understanding dawning slowly? Because photographs were proof.

In a world where black families were dismissed, their testimonies ignored, their very humanity questioned in courts of law.

A photograph was different.

A photograph couldn’t be denied.

It showed you existed, showed you owned property, showed you were a person with dignity and family and rights.

These families were creating evidence of their legitimacy, their respectability, their humanity.

If they were ever accused, if they were ever dragged into court, they would have proof that they were upstanding citizens, not criminals.

But they were also documenting something else, Sarah realized.

Something hidden in plain sight.

She returned to the Williams family entry and noticed a small notation in the margin, so faint she’d almost missed it.

“Rm, usual precautions.

RM.

” She flipped through other evening sessions.

The same initials appeared sporadically.

Robert Mitchell, Richard Moore.

Then she found it five pages later in a different handwriting.

Probably an assistance note.

RM departed successfully via back entrance.

Package secured.

Package.

The dehumanizing language of the era for a person being transported to freedom.

Back at the historical society, Sarah laid the Williams photograph under her highest resolution scanner.

Modern digital technology could see what the naked eye couldn’t, capturing minute details, enhancing shadows, revealing hidden elements in historical images.

She zoomed in on the section that had caught her attention.

The strip of mirror partially visible behind the draped backdrop curtain.

At 400% magnification, the reflection was still blurred, but she could make out shapes.

At 800%, patterns emerged.

At 1200%, her heart nearly stopped.

There was definitely someone there.

A figure partially obscured standing in the space behind where the photographer would have been positioned.

The angle was wrong for it to be the photographer himself.

This person was off to the side in the shadows, deliberately out of the primary shot.

She could make out dark clothing, a suggestion of a face, hands clutched together at chest level and in posture that read as tension, hope, fear.

Sarah adjusted the contrast and brightness, working carefully to enhance without distorting.

Historical photograph analysis was as much art as science.

Pushed too far, and you created details that weren’t there.

But done carefully, you could reveal what had always existed, but never been noticed.

The figure became clearer.

A woman, Sarah thought, though the image quality made certainty impossible.

Young, perhaps 20 or 25.

Her dress was simpler than Martha Williams elegant outfit, rougher fabric, no lace, the clothing of someone with fewer resources, and her expression, even blurred and ghostly in the accidental mirror reflection, carried unmistakable emotion, desperate hope.

Sarah sat back, her mind assembling the pieces.

The Williams family had come to Whitman and Sun’s photography for an evening session.

when the studio would be empty, when the street outside would be dark, when no one would see who entered or left through the back entrance.

They’d brought their children, dressed everyone in their finest clothes, and posed for an expensive portrait that documented their respectability and legitimacy.

And while they did so, someone else was there, someone who couldn’t be in the photograph, couldn’t be officially recorded, couldn’t risk being seen, someone who needed to hide in the shadows while this family created their alibi.

Young Samuel, just 6 years old, hadn’t been distracted or disobedient when he looked away from the camera.

He’d been looking at her, at the person his family was protecting, at the woman who would within hours probably be moved further along the network toward actual freedom.

And little Samuel, in that moment of childhood honesty, couldn’t help but look at the most important person in the room, even if no one else was supposed to know she was there.

Sarah pulled up the newspaper clipping again.

The investigation had happened in July 1868.

The photograph was dated July 23rd, 1868.

The timing was too precise to be coincidence.

The Williams family had been investigated, questioned, their home searched, and within days they’d created a permanent visual record showing they were a proper, respectable family.

Surely not the kind of people who would break the law.

The photograph was an alibi, and simultaneously, hidden in its reflection.

It was a confession.

But there was something else.

Sarah zoomed in on Samuel’s face, studying his expression.

That wasn’t just a child’s wandering attention.

His eyes were focused, intent, and the slightest suggestion of something at the corner of his mouth, not quite a smile, but close.

a tiny expression of complicity of knowing he was part of something important.

He’d been looking at that woman deliberately, making sure in his child’s way that she was okay, keeping watch even while his body stood still for the camera.

This little boy had been a lookout.

Dorothy Peterson arrived at the historical society carrying a worn cloth bag.

She was 78 with silver hair and sharp eyes that studied Sarah carefully before sitting down.

“Show me what you found,” she said without preamble.

Sarah laid out the enhanced images on the table.

The original photograph, the magnified section showing the mirror’s reflection, the studio ledger entry, the newspaper clipping about the investigation.

Dorothy’s hand rose to her mouth.

Oh my god, she was really there.

You knew? Sarah asked gently.

I thought I thought it was just a story, something my great-grandfather said when he was old, when his mind might have been.

I Dorothy trailed off, touching the photograph with one trembling finger.

He told me they helped people.

That before he started school, his house was a stop on the railroad.

But that was before the war.

I thought I thought he was confused about the timing.

The railroad didn’t stop with abolition.

Sarah explained it couldn’t.

In isolated parts of the South, some people were still being held illegally.

The networks that existed before the war continued, but in even deeper secrecy because now the activity was unambiguously criminal.

No more legal gray areas.

If caught, your family could have been imprisoned.

Dorothy nodded slowly, her eyes filling with tears.

He said he remembered a woman, just one specifically.

Said she stayed in their attic for 3 days, and he would sneak up to bring her food.

Said she sang to him once, very quietly, a song he never forgot.

She hummed a few notes.

Old spiritual, its melody carrying sorrow and hope in equal measure.

He was 6 years old, Dorothy continued.

And he said he knew even then that if anyone found out, his whole family would be destroyed.

His father could lose his business.

His mother could be arrested.

They could lose their home.

But he also knew it was right, that helping her was the most important thing his family had ever done.

Sarah pulled out another document she’d found, a passenger manifest from a ship that left Philadelphia for Nova Scotia in late July 1868.

I think I found her.

A woman listed only as RM.

Those same initials from the studio ledger.

No full name, no age, no origin, just those letters and a notation that her passage was paid by a private charity.

Did she make it? Dorothy whispered.

Did she escape? The ship arrived safely.

After that, she disappeared into Canada.

No records, no trail, which means she probably succeeded.

She got to live the life she deserved.

They sat in silence for a moment, looking at the photograph.

A family standing proud and dignified, creating evidence of their respectability.

And hidden in the reflection, invisible unless you knew to look.

Proof of their courage.

The photograph was taken right after the investigation, Sarah explained.

Your family was sending a message.

Look at us.

We’re respectable citizens, property owners, educated people.

We would never break the law, but they had broken the law.

They’ just finished breaking it, in fact, and somehow they managed to hide the evidence in plain sight.

Dorothy smiled through her tears.

That sounds like my great-grandfather.

He told me once that the bravest people are the ones who look absolutely ordinary, who do extraordinary things and then go back to their normal lives like nothing happened.

She reached into her cloth bag and pulled out an old leather journal, its pages yellowed and brittle.

I brought this.

It was Samuels.

He wrote in it later in his life in the 1920s and30s.

I haven’t opened it in years, but I thought maybe there’s something in here that can help.

Sarah accepted the journal reverently.

On the first page, in careful handwriting, Samuel Williams had written for my grandchildren so they know what their family stood for.

Sarah spent that evening reading Samuel Williams journal by lamplight in her apartment, afraid to bring the fragile document back to the society’s fluorescent lit archive.

His handwriting was elegant, educated, the words of a man reflecting on a life that had spanned from just after slavery to the jazz age.

Most entries were mundane.

Family dinners, business dealings, church services, but scattered throughout were passages that made Sarah’s breath catch.

August 12th, 1923.

Today marks 55 years since the photograph.

I found myself thinking about her again, as I do every July.

I was only six, but I remember her face as clearly as I remember my own children’s.

She was terrified and brave in equal measure.

Mother told me years later that she’d walk 90 miles to reach Philadelphia, following stars and instructions whispered by people whose names she never learned.

Three days in our attic and I would creep up the stairs with bread and water, pretending I was a soldier on a secret mission.

She thanked me once, called me her little guardian.

I didn’t understand then what we were doing.

Not really, but I knew it was important.

I knew we were hiding her from people who wanted to hurt her.

And I knew that if I told anyone, not even my best friend at school, my whole family would be destroyed.

Sarah turned the pages carefully, finding another entry from years later.

November 3rd, 1931.

A young man came to my shop today, asking questions about the old days, the years right after the war.

Said he was a historian, wanted to understand how the railroad operated in Philadelphia.

I told him what everyone tells historians, that it was heroic work done by brave people, but that most of the details are lost to time.

I didn’t mention the photograph.

I didn’t mention RM Rachel Martin, though I didn’t learn her full name until 1889 when she wrote to my mother from Toronto.

By then, I was a grown man with children of my own.

And reading that letter, knowing she’d made it, knowing she’d built a life in freedom, made me cry like I hadn’t since childhood.

Mother saved the letter.

I hope my daughter saves it, too.

Someday, when enough time has passed that truth won’t endanger anyone, I hope someone finds it and understands what ordinary families did in extraordinary times.

Rachel Martin.

Sarah wrote the name down, her hand shaking slightly.

A full name to attach to the ghostly reflection in the mirror.

She continued reading.

July 23rd, 1935.

67 years ago today, we took that photograph.

I’m 81 now.

The last one living who was in that room.

Thomas Jr.

died in 1918.

Clara in 1929.

Mother and father have been gone for decades.

The photographer, Mr.

Whitman’s son, died last year.

I attended his funeral and afterward his grandson asked if I’d known his grandfather well.

I said only as a customer.

But the truth is, Mr.

Whitman Jr.

was as brave as any of us.

He risked his business, his reputation, his freedom by opening his studio after dark for families like mine.

By looking the other way when someone extra slipped in through the back door, by creating portraits that served as alibis while documenting, accidentally or perhaps not, the truth and reflections and shadows.

I wonder if he knew the mirror caught her.

I wonder if he left it there deliberately, a secret witness for future generations.

I’ll never know.

But I like to think he did.

I like to think that photograph was his way of saying this happened.

These people were heroes.

and someday when it’s safe, someone will see.

The final relevant entry was dated just weeks before Samuel’s death in 1961.

I told my great granddaughter Dorothy about the photograph today.

She’s 10, bright as summer, and she asked me why we looked so serious in old pictures.

I told her it wasn’t that we were serious, it’s that we were brave.

I told her that photograph was taken on the most dangerous day of my life, and that it proved my family were heroes, even though no one could ever know.

She looked confused, and I suppose I was rambling.

But I want her to understand, even if not now, then someday.

Ordinary people doing extraordinary things.

That’s what holds the world together.

Not presidents or generals, but families opening their doors in the dark.

Photographers dimming their lights so someone can slip away unseen.

Six-year-old boys keeping secrets that could destroy everything they love.

That photograph sits in my daughter’s drawer now.

I hope it survives.

I hope someone finds it and understands.

I hope the mirror tells its story.

Sarah closed the journal gently, tears streaming down her face.

Samuel had known.

He’d hoped.

And now, 157 years later, someone had finally seen.

Finding Rachel Martin proved more difficult than Sarah anticipated.

The ship manifest confirmed a woman with those initials had traveled to Nova Scotia.

But Canadian records from the 1860s were incomplete.

Especially for black refugees who often used assumed names or simply disappeared into communities that protected them from American authorities who sometimes pursued escaped slaves even across international borders.

Sarah contacted colleagues at archives in Toronto, Halifax, and Montreal.

She posted in historical forms.

She reached out to genealogologists specializing in African Canadian history.

Three weeks later, she received an email from Dr.

James Robinson, a retired professor in Toronto who’d spent 40 years documenting black Canadian settlements in the post civil war era.

I think I found your Rachel Martin.

His email read, though she went by Rachel Morrison in Canada.

Common practice to change surnames for safety.

Census records show a Rachel Morrison arriving in Toronto in August 1868, age approximately 24 from Pennsylvania.

She married in 1871 to a man named Frederick Morrison, a carpenter.

They had four children.

She died in 1921, age 77, and is buried in Toronto’s Necropolis Cemetery.

Attached were scanned documents, a marriage certificate, birth records for the children, a death certificate, and one more item, a newspaper clipping from the Toronto Globe, dated 1919, showing an elderly Rachel Morrison being honored by the local church for 50 years of community service.

The photograph in the newspaper was small and grainy, but Sarah could make out an elderly woman with kind eyes and white hair surrounded by church members.

The caption read, “Mrs.

Rachel Morrison, beloved member of First Baptist Church, celebrated for her lifetime of service to new arrivals in Toronto, helping families transition to freedom in Canada.

She’d spent her life doing for others what had been done for her.

Sarah sat back overwhelmed.

The ghostly figure in the mirror reflection had lived, had married, had children, had built a life, had taken the terrifying courage of that journey and transformed it into decades of helping others.

But there was more.

Dr.

Robinson’s email continued, “One of Rachel Morrison’s great-granddaughters still lives in Toronto.

Her name is Patricia Morrison Chen and she’s a retired school teacher.

I took the liberty of mentioning your research to her and she’s very interested in speaking with you.

She knew her great-grandmother had escaped slavery, but the family stories were always vague about the details.

Her email is below.

Sarah contacted Patricia immediately.

They arranged a video call for the following evening.

Patricia was in her 70s with silver braids and Rachel’s same kind eyes.

Tell me everything, she said the moment they connected.

My great-grandmother never spoke about her escape.

She told my grandmother only that angels in Philadelphia saved her life and that she owed everything to a family whose name she promised never to speak.

Sarah shared the photograph, the enhanced mirror reflection, Samuel’s journal entries.

She explained about the Williams family, their evening session, the investigation that had nearly destroyed them.

Patricia wept openly.

She kept her promise.

She never told us their names.

Even when she was dying, even when my grandmother begged her for details, she said it was too dangerous that those families could still face consequences.

She wiped her eyes.

But she wrote something.

Wait.

Patricia disappeared from view, returning moments later with a wooden box.

Great-g grandandmother’s things.

Letters, documents, a few personal items.

She opened the box carefully and withdrew a folded piece of paper yellowed with age.

This was pinned inside her Bible.

We found it after she died.

None of us understood what it meant.

She held it up to the camera.

In faded ink and careful handwriting were four lines.

July 23rd, 1868.

The day I became free.

Thanks to the blacksmith’s family and the little boy who watched over me.

Sarah’s vision blurred with tears.

“That’s Samuel.

He was 6 years old.

He brought her food, kept her secret.

She never forgot him.

” “And now we know his name,” Patricia whispered.

“After all these years, we can finally say thank you.

” With Rachel Martin’s identity confirmed and Patricia’s permission to share the story.

Sarah returned to the studio ledgers with renewed purpose.

If the Williams family and Rachel Martin represented one successful passage, how many others were documented in those evening sessions? She spent two months cross-referencing names, dates, and records.

The pattern became clear.

Approximately twice a month between 1866 and 1872, Whitman and Sons Photography conducted special arrangement evening sessions for black families.

The studio ledgers used coded language, package secured, departure confirmed, safe arrival noted.

You would Sarah identified 17 families total who had participated in the network.

Using census records, city directories, and archived newspaper articles, she traced their stories.

The Patterson family, who ran a boarding house that served as temporary shelter.

The Hughes family, whose wagon-making business provided cover for transporting people hidden in false bottoms.

The Morris family, whose connections to Philadelphia’s black church network, helped identify new arrivals who needed assistance.

Each family had taken extraordinary risks.

Each had been investigated at least once, and each had created photographic evidence of their respectability, their legitimacy, their status as upstanding citizens who would never dream of breaking the law.

The photographs served as alibis and Sarah realized as insurance.

If any family member was arrested, these portraits could be presented in court as evidence of character.

“Look at us,” the photograph said.

“We are property owners, business people, educated families.

Would people like us commit crimes?” But there was another layer to the story that Sarah uncovered through local abolitionist society records.

The photographer, James Whitman Jr.

, wasn’t just looking the other way.

He was an active participant in the network.

His father, James Whitman, Senior, had been an abolitionist before the war, using his studio to create photographs of formerly enslaved people that documented their humanity and helped with legal cases, proving their freedom.

After his father’s death in 1865, James Jr.

had continued the work in secret, using evening sessions to provide safe space for families involved in the illegal but morally necessary work of helping people still trapped in de facto slavery.

The studio’s basement entrance opened onto an alley that connected to a network of passages between buildings, remnants of the original underground railroad infrastructure.

People could slip in unseen, wait in the studios back room while a family had their portrait taken, then slip out again when the streets were empty.

Whitman documented each passage in his personal journal, which Sarah found in the archives.

His entries were brief but telling.

Evening session, Williams family RM departed safely.

Fourth successful passage this month.

Father would be proud.

Authorities asking questions about evening activities.

Increased caution necessary, but the work continues.

Portrait of the Hughes family, infant included.

First baby born free in Canada to a family we assisted.

Small victories.

James Whitman Jr.

had died in 1934, having operated his studio until 1890 before retiring.

His obituary made no mention of his role in the postwar underground railroad.

He’d taken the secret to his grave, protecting the families he’d helped even in death.

But the photographs remained, each one a testament to ordinary people doing extraordinary things.

Each one hiding truth in shadows and reflections, waiting for someone to finally see.

Six months after discovering the reflection in the Williams family photograph, Sarah stood in the Philadelphia Historical Society’s main gallery, watching visitors examine the exhibition she’d curated.

Hidden in plain sight, Philadelphia’s post-war underground railroad occupied two rooms and told the story she’d uncovered.

The Williams family photograph held the central position displayed with side-by-side comparisons showing the original image in the enhanced version that revealed Rachel Martin’s reflection.

Around it hung 16 other family portraits from the evening session, each with detailed explanations of who the families were, what risks they’d taken, and what had happened to the people they’d helped.

Interactive displays let visitors zoom in on the photographs, searching for their own hidden details.

Video interviews with descendants played on loop.

Dorothy Peterson, Patricia Morrison Chen, and others whose ancestors had been part of the network.

But it was Samuel Williams journal that drew the longest lines.

Displayed in a climate controlled case open to the page where he’d written about being Rachel’s little guardian.

It connected past and present in a way that made visitors stop and read, their faces reflecting wonder and sorrow and pride.

Dorothy and Patricia stood together near the Williams photograph, meeting for the first time despite being connected by a century old act of courage.

They’d spent the morning sharing family stories, weeping and laughing in equal measure.

My great-grandfather would have loved this.

Dorothy said, gesturing at the exhibition.

All his life, he hoped someone would understand.

And now thousands of people will see.

Patricia nodded, staring at the reflection in the mirror.

I’m looking at my great-grandmother’s face after all these years of wondering what she looked like at that age, what she’d been through.

Here she is, scared and brave and about to be free.

A young boy, perhaps seven, approached the photograph with his parents.

He pointed at Samuel Williams.

Why is he looking over there instead of at the camera? his mother read the placard because he was watching over someone who needed help, someone who was hiding.

He was very brave.

The boy studied the image seriously.

Like a superhero.

Exactly like a superhero, his father said, except real.

Sarah watched the family move through the exhibition.

The boy asking questions at every display, absorbing the story of ordinary people who’d risked everything to do what was right.

This, she thought, was why history mattered, not just as facts and dates, but as proof of human courage, for the capacity for ordinary people to be extraordinary when it mattered most.

The exhibition would travel after its Philadelphia run to Toronto to Washington DC onto cities across North America where similar networks had operated in secret.

Rachel Martin’s story and the Williams family’s courage would be preserved, studied, celebrated.

That evening, after the gallery closed, Sarah stood alone in front of the Williams photograph.

She thought about Samuel, six years old, keeping a secret that could destroy his family.

About Rachel walking 90 miles to freedom, trusting strangers with her life.

About Thomas and Martha Williams opening their home despite the risks.

About James Whitman using his art to protect people while documenting their humanity.

And she thought about the photograph itself.

How a simple family portrait taken in a moment of fear and courage had carried it secret for 157 years, waiting patiently for someone to finally see what little Samuel had seen that day.

The truth hidden in a reflection.

Courage preserved in silver and light.

A family’s legacy finally understood.

Three years after the exhibition opened, Sarah received an unexpected email.

The subject line read, “You helped me find my family.

” The sender was Marcus Williams, a 32-year-old software engineer from Seattle.

His message explained that he’d visited the exhibition during its West Coast tour and recognized his own last name.

Following up with genealological research, he’d traced his lineage back to Thomas Williams Jr.

, Samuel’s older brother in the photograph.

I never knew.

Marcus wrote, “My father told me we had Philadelphia roots, but he didn’t know the details.

Finding out that my great great great-grandfather was part of the Underground Railroad, that my family risked everything to help people.

It’s changed how I see myself, how I understand what I’m capable of.

” Sarah smiled, reading his words.

“This was the impact she’d hoped for.

Not just preserving history, but making it alive and relevant, showing people that courage and justice aren’t abstract concepts, but choices made by real people whose blood still flows in living descendants.

” The exhibition had sparked dozens of similar discoveries.

Families across North America had researched their own genealogies, finding connections to the network Sarah had documented.

Some discovered ancestors who’d been helped, like Patricia.

Others discovered ancestors who’d helped, like Marcus.

Each discovery added another thread to the tapestry of understanding.

Dorothy Peterson had passed away at 81, but before her death, she’d recorded an oral history that now played in the exhibition’s final room.

Her voice, warm and clear, told Samuel’s story in her own words, ensuring that his memories would survive, even after those who’d heard them firsthand were gone.

Patricia Morrison Chen had written a book about Rachel Martin’s life in Canada, using the photograph, and that Sarah’s research as a starting point to explore what life had been like for black refugees building new communities in Toronto.

The book had become required reading in Ontario schools.

The photograph itself had become iconic, reproduced in textbooks, featured in documentaries, displayed in museums.

But for Sarah, its power lay not in its fame, but in what it represented.

The idea that ordinary objects closely examined can reveal extraordinary truths.

She’d built a career on that principle, helping other researchers and families uncover hidden stories in old photographs.

But the Williams family portrait remained special, the case that had taught her to look beyond the obvious, to search for reflections and shadows and the evidence people left deliberately or accidentally in the margins of their documented lives.

On the anniversary of discovering Rachel Martin’s reflection, July 23rd, the same date the photograph had been taken 158 years earlier, Sarah returned to Philadelphia.

She stood on Race Street where the studio had been, imagining that evening in 1868, the Williams family arriving after dark, children dressed in their finest clothes, hearts pounding with fear and determination.

Rachel Martin slipping in through the back entrance, hiding in shadows while the family created their alibi.

James Whitman setting up his camera, positioning lights, carefully arranging the scene.

and six-year-old Samuel standing still as his parents had taught him, but unable to stop his eyes from drifting to the person who mattered most in that room, the person who’d sung to him, whom he’d protected, whom his family was saving at enormous risk.

In that moment of childhood honesty, Samuel had done what no one else could.

He’d looked at the truth, and through his looking, had preserved it for future generations to find.

Sarah thought about all the photographs still waiting in archives and atticts, in museum storage, and private collections.

How many other stories were hiding in reflections and shadow? How many other Samuel Williams’es had preserved truth through small unconscious acts of witness? History wasn’t just what was deliberately recorded.

It was also what accidentally survived, what was hidden in margins, what patient researchers could uncover by looking closely at what everyone else overlooked.

She pulled out her phone and took a picture of the building where it had all happened.

In her photograph’s reflection, caught in the cafe’s glass window, she could see other people on the street behind her, walking, talking, living their ordinary lives.

Ordinary people doing ordinary things until the moment came when they’d have to decide whether to be extraordinary.

Just like the Williams family, just like Rachel Martin, just like everyone whose courage captured accidentally or deliberately in silver and light waited patiently for someone to finally

News

What Scientists Just FOUND Beneath Jesus’ Tomb In Jerusalem Shocked The Whole World Archaeologists And Researchers Have Unearthed Astonishing Artifacts And Hidden Structures That Could Rewrite History And Reveal Secrets Long Buried — Click The Article Link In The Comment To Discover The Shocking Discoveries, Obscure Details, And Theories That Are Stunning Experts Everywhere.

Beneath the heart of Jerusalem, under centuries of worn stone, a hidden world of human history quietly preserves the stories…

AI Makes a Breakthrough Discovery in the Shroud of Turin

For centuries, the Shroud of Turin has hovered uneasily between faith, skepticism, and science. To some, it is the most…

Is a GREAT DARKNESS Truly Near—and Why Does a FINAL WARNING Center on DECEMBER 29–31?

A Great Darkness Approaches: Final Warning from Pope Leo XIV In a compelling and thought-provoking message, Pope Leo XIV recently…

AI FOUND an Impossible Signal in the Shroud of Turin, Scientists Went Silent

The Shroud of Turin: A Two-Thousand-Year Enigma Bridging Science and Mystery For centuries, the Shroud of Turin has captivated both…

10 Reforms That Will SHOCK YOU! Pope Leo XIV Just Changed the Catholic Church FOREVER!

Pope Leo XIV: A Revolution of Compassion and Humility in Just 19 Days In an era where the Catholic Church…

7 Shocking Changes Pope Leo XIV Just Made – Is the Church Ready?

Pope Leo XIV: Seven Transformative Reforms Reshaping the Catholic Church In just a short span of time, Pope Leo XIV…

End of content

No more pages to load