It was just a photo between friends.

But historians have uncovered a dark secret.

Dr.James Patterson had spent his academic career studying race relations in the postreonstruction south, focusing particularly on the rare documented cases of genuine friendships that crossed the color line in an era when such relationships were not merely discouraged but actively dangerous.

In August 2019, while cataloging a collection of photographs donated to the University of Mississippi archives, he discovered an image that stopped him completely.

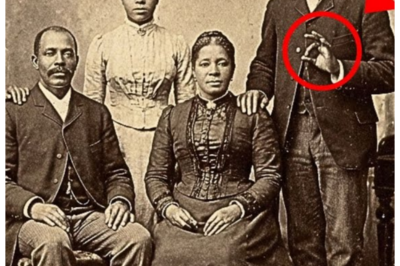

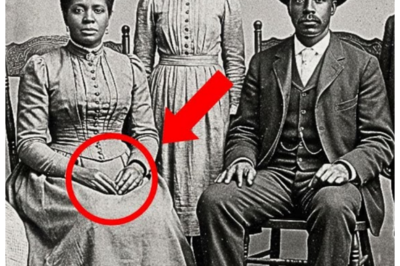

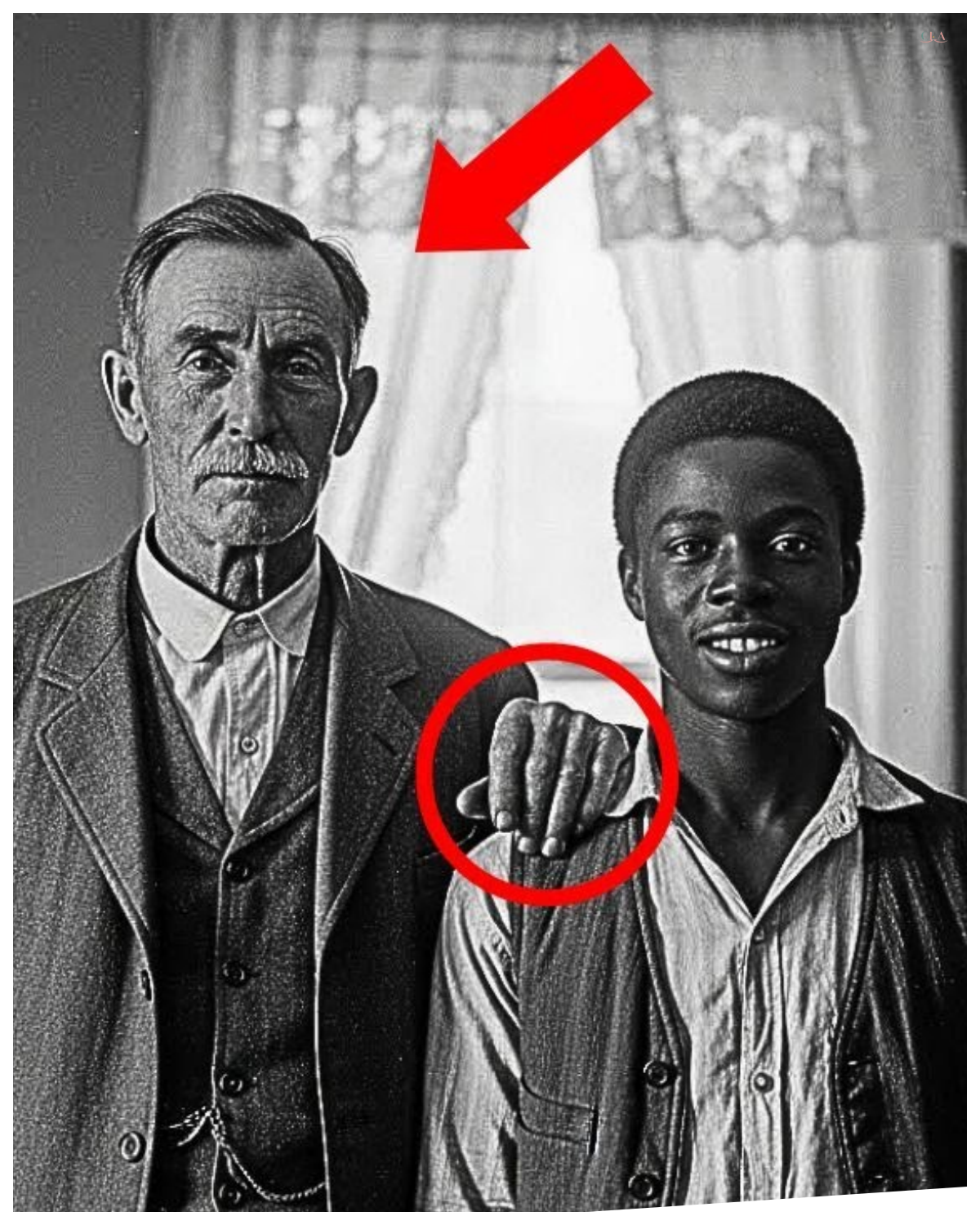

The photograph dated April 1899 showed two men in what appeared to be the parlor of a modest but respectable home.

The room’s details were visible in the background.

A simple wooden mantelpiece, lace curtains at the window, a small bookshelf, family photographs on the wall, but it was the two men who commanded attention.

And on the left stood Thomas Brennan, a white man of approximately 67 years, dressed in a worn but clean suit.

His face was weathered, lined with deep creases that spoke of decades spent outdoors.

His hand rested on the shoulder of the younger man beside him, not formally, not posed for propriety, but with genuine affection, the kind of gesture that couldn’t be faked.

The younger man was Daniel, identified only by his first name in the notation on the photograph’s backing.

He appeared to be in his early 20s, black, dressed in clothing that was simpler, but equally well-maintained.

What struck Patterson most was Daniel’s expression.

He was smiling, genuinely smiling, with an ease and comfort that was extraordinarily rare in photographs of black Americans from this era, especially when photographed with white people.

Both men looked directly at the camera with expressions that suggested mutual respect, even warmth.

There was no hint of the rigid hierarchy that typically defined interactions between white and black people in Mississippi in 1899.

This was not a photograph of employer and servant or patron and dependent.

This looked like a photograph of friends.

Patterson turned the photograph over carefully.

On the back in faded ink, someone had written Thomas Brennan and Daniel, April 14th, 1899.

May this friendship endure.

The handwriting was educated, the sentiment sincere.

Below that, in different shakier handwriting and darker ink, added later, Patterson guessed, were words that made his breath catch.

It did not.

God forgive me.

Patterson sat back in his chair, the photograph still in his hands.

Something terrible had happened after this image was taken.

something that had haunted whoever wrote those final words.

The contrast between the hopeful inscription and the anguished postcript suggested a story of loss, betrayal, or tragedy, perhaps all three.

He began the work he knew well, the methodical reconstruction of lives from fragmentaryary evidence.

He started with census records, searching for Thomas Brennan in Mississippi in the 1890s.

He found several possibilities, but one entry from the 1900 census stood out.

Thomas Brennan, white male, age 68, occupation listed as farmer, residing in Talahache County, Mississippi.

The entry noted he lived alone.

Patterson cross- referenced property records and found that Thomas Brennan had owned a small farm 40 acres outside the town of Charleston, Mississippi.

This was not a plantation.

Thomas was not part of the wealthy planter class.

He was a small farmer working his own land.

Finding information about Daniel proved more difficult.

The 1900 census showed no Daniel living with or near Thomas Brennan.

Patterson expanded his search, looking through local newspapers from 1899, church records, and court documents.

What he found would lead him into one of the most painful stories he had ever uncovered.

Dr.

Patterson delved into Thomas Brennan’s background, searching for clues about how a white farmer in Mississippi in 1899 could have developed a genuine friendship with a young black man.

The answer lay in Thomas’s past, documented in military records that Patterson found in the National Archives.

Thomas Brennan had served in the Union Army during the Civil War.

His enlistment record from 1862 showed he had joined the 33rd Illinois Infantry Regiment at age 30, listing his occupation as farmer and his birthplace as Illinois.

His service record indicated he had fought in multiple campaigns, including the siege of Vixsburg in 1863, where his regiment had been part of the Union force that captured this crucial Mississippi River city.

Patterson found something else in the military records.

Thomas had been wounded twice during the war, the second time seriously at the Battle of Nashville in December 1864.

He had been honorably discharged in early 1865 due to his injuries and had received a small military pension.

What brought Thomas Brennan from Illinois to Mississippi after the war? Patterson found the answer in reconstruction era land records.

In 1867, Thomas had purchased 40 acres in Tallahassee County under the Southern Homestead Act, a federal program that offered land to settlers, including Union veterans, in former Confederate states.

The program was intended partly to reshape southern society by introducing northerners who would support reconstruction policies.

Thomas had been one of thousands of Union veterans who moved south seeking new opportunities.

But by 1899, reconstruction had long since ended, replaced by violent white supremacist redemption governments that had systematically stripped black Americans of their rights and reestablished racial hierarchy through law and terror.

Union veterans who remained in the South found themselves isolated, often resented by white southerners who viewed them as occupiers and traders.

Patterson discovered more about Thomas through county records and local histories.

Thomas had never married, had no children, and apparently lived a quiet life farming his small property, but there were hints that he had not entirely abandoned his union principles.

In 1875, a local newspaper briefly mentioned that Thomas Brennan had testified on behalf of a black farmer in a property dispute with a white neighbor, an extraordinary and dangerous act in that time and place.

The black farmer had won the case, and the newspaper article noted darkly that certain northern elements continue to interfere in matters that do not concern them.

Patterson found another reference in an 1882 county commission meeting minutes.

Thomas Brennan had appeared to protest the closure of a school for black children, arguing that education should be available to all citizens.

His protest was dismissed and the school was closed anyway.

These small acts of resistance painted a picture of a man who decades after the war ended still believed in the principles he had fought for.

But believing in equality and actually forming friendships across the color line were different things.

In the Mississippi of the 1890s, such friendships were not merely unusual.

They were seen as threats to the social order.

Patterson needed to understand how Thomas and Daniel had come to know each other and why they had risked so much to maintain their friendship.

Finding Daniel’s full identity proved challenging.

Daniel was a common name, and many records of black Americans from this era were incomplete, inconsistent, or simply never created.

But Dr.

Patterson was persistent, and gradually he pieced together the story.

In church records from the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, Mississippi, Patterson found a baptism entry from 1877.

Daniel, son of Clara, born 1877.

No father was listed.

This was common for children born to unmarried women, or as Patterson suspected in this case, children born to women who had been enslaved and whose children’s fathers were unknown or unacknowledged.

Patterson found Clara in the 1880 census.

Clara Freeman, black female, age 32, domestic servant.

Living with her was Daniel Freeman, black male, age three.

So Daniel’s full name was Daniel Freeman, a surname commonly adopted by formerly enslaved people after emancipation.

Clara appeared in subsequent census records, always working as a domestic servant for various white families in Talahache County.

Daniel appeared with her through 1890, listed as attending school, remarkable for a black child in Mississippi during this period when educational opportunities for black children were severely limited and often non-existent.

Then Patterson found something crucial in county court records from 1893.

Clara Freeman had died that year.

Cause of death listed as pneumonia.

She was only 45.

The records showed that her son Daniel, then 16, had been left with no family and no means of support.

This was where Thomas Brennan entered Daniel’s life.

Patterson found a notation in Thomas’s property records from late 1893.

Daniel Freeman employed as farm laborer residing on property.

Thomas had taken Daniel in, given him work and a place to live when he had nowhere else to go.

But their relationship had clearly evolved beyond employer and employee.

Patterson found evidence in surprising places.

In 1895, Thomas had paid for Daniel to attend a carpentry training program offered by a missionary organization, an investment of money and time that suggested genuine care for Daniel’s future.

In 1897, records showed that Thomas and Daniel had traveled together to Memphis to purchase farm equipment.

Unusual for a white man and black youth to travel together in that era.

The photograph from 1899 taken in Thomas’s home rather than in a formal studio suggested intimacy and trust.

Having a photograph taken was expensive and significant in that era.

The fact that Thomas had arranged for this photograph to be taken in his own parlor with Daniel positioned as an equal was extraordinary.

Patterson found the photographers’s business records in a Memphis archive.

The photograph had been taken by a traveling photographer named William Hayes, who made circuits through rural Mississippi taking portraits for families who couldn’t travel to city studios.

Hayes’s ledger for April 1899 included an entry.

Brennan residents, two subjects, one exposure, paid $2.

Two subjects, one exposure.

Thomas and Daniel had been photographed together deliberately as a unit, not in separate portraits.

This was Thomas’s choice, Thomas’s statement.

In the violently segregated world of 1899 Mississippi, where laws and customs rigidly separated white and black people in every aspect of life, Thomas Brennan had created a photograph documenting his friendship with a young black man, displaying it in his home as evidence of a bond that defied every social norm.

What had happened between April 1899 when that photograph was taken with its hopeful inscription and the later edition of those anguished words, “It did not.

God forgive me.

” Dr.

Patterson’s breakthrough came when he found a series of newspaper articles from July 1899 in the Charleston County Press, a weekly newspaper serving the area where Thomas Brennan lived.

The headlines told a chilling story.

Negro arrested for theft from prominent family.

Stolen items found in Negro’s possession.

Swift justice demanded by citizens.

The articles described how Daniel Freeman, a negro youth of approximately 22 years, had been accused of stealing jewelry and money from the home of the Garrett family, one of the wealthiest white families in the county.

According to the newspaper account, Mrs.

Sarah Garrett had discovered valuable jewelry missing from her bedroom.

She had immediately suspected Daniel, who had allegedly been seen near the property days before.

When the sheriff searched the small cabin where Daniel lived on Thomas Brennan’s property, he reportedly found some of the stolen items hidden under Daniel’s bed.

Daniel was arrested and jailed.

The newspaper articles included statements from Mrs.

Garrett demanding appropriate punishment and from various white citizens calling for swift justice and expressing outrage that criminal elements were being harbored by those who should know better.

A clear reference to Thomas Brennan’s Union background and his employment of Daniel.

But Patterson’s experience with historical newspapers, particularly southern newspapers from this era, had taught him to read critically.

These publications often promoted white supremacist narratives and justified violence against black Americans.

He needed other sources to understand what had really happened.

He found those sources in unexpected places.

First, in the records of the Mississippi chapter of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, an organization that occasionally advocated for justice, even when it was unpopular.

In meeting minutes from August 1899, a member named Elizabeth Morrison had raised concerns about Daniel Freeman’s case, noting that the evidence presented seems questionable, and the haste with which judgment is being pursued is concerning.

Her concerns had been dismissed by other members who insisted they should not interfere in legal matters.

Second, Patterson found a letter in the papers of a northern missionary teacher who had worked in Mississippi during this period.

The teacher, Margaret Stevens, had written to her sister in Massachusetts in July 1899.

There’s a terrible situation developing here involving a young colored man who I believe has been falsely accused.

He’s intelligent, hardworking, and has been employed by a Union veteran farmer who speaks highly of his character.

But the accusation comes from a powerful family.

Truth seems to matter little when race and power are involved.

Most revealing, Patterson found entries in Thomas Brennan’s own records, a journal that Thomas had kept sporadically.

The entries from July 1899 were extensive, written in obvious anguish.

July 12th, 1899.

They have arrested Daniel.

The charges are lies.

I know this boy.

He would never steal.

He has lived on my property for 6 years.

He has worked honestly, attended church, harmed no one.

But Mrs.

Garrett has accused him, and that is all that matters to them.

They found jewelry in his cabin, but how did it get there? Daniel swears he never saw those items before.

Someone planted them.

I am certain of it.

Dr.

Patterson continued reading Thomas Brennan’s journal entries from July 1899, and a fuller picture emerged of what had actually happened.

Thomas had immediately begun investigating the accusation against Daniel, knowing that in the legal and social climate of Mississippi in 1899, a black man accused by a white woman had virtually no chance of a fair hearing.

Thomas’s journal entry from July 14th, 1899 recorded what he had learned.

I spoke with Daniel in jail today.

The sheriff allowed me only 10 minutes.

Daniel told me the truth of what happened.

Three weeks ago, he was making a delivery of vegetables to town.

I had sent him with our surplus crops to sell at the market.

On his way, he passed the Garrett property and saw Mrs.

Garrett’s son, Robert, arguing violently with his mother near the garden.

Robert was demanding money.

Mrs.

Garrett was refusing.

Robert became enraged and struck his mother.

Daniel witnessed this and without thinking called out, “Stop.

” Robert saw Daniel and threatened him, saying, “If he ever spoke of what he saw, he would regret it.

” The journal continued, “Daniel told me he tried to forget what he had witnessed, but it troubled him.

Robert Garrett is known to be a gambler and a drunk who has squandered much of the family’s money.

Two weeks after the incident, Daniel saw Robert in town at night, leaving the assayair’s office, the place where people sell jewelry and gold.

Robert was carrying a bag and counting money.

Daniel realized then what Robert had done, stolen from his own mother to pay his debts, then blamed Daniel to avoid consequences.

Patterson cross- referenced this account with other records.

He found evidence that Robert Garrett did indeed have a reputation for gambling in debt.

A Memphis newspaper from 1898 mentioned Robert Garrett in connection with gambling debts at a riverboat casino.

County court records showed that Robert had been sued twice by creditors in 1897 and 1898.

Thomas’ journal entry from July 16th recorded his confrontation with Robert Garrett.

I went to the Garrett house today and demanded to speak with Robert.

I told him I knew what he had done stolen from his own mother and framed Daniel.

Robert laughed at me.

He said, “Who will believe you, old man? Who will believe a yen or r over a white man’s word? The evidence is in his cabin.

He will hang or go to the chain gang and there’s nothing you can do about it.

I told him I would testify to Daniel’s character that I would fight this injustice.

Robert said, “Then you’ll hang beside him.

Not I’m our lover.

” And he meant it.

This was the reality of Mississippi in 1899.

Even with Thomas as a witness, even with evidence of Robert’s debts and suspicious behavior, the word of a white woman accusing a black man was effectively unassalable.

The legal system was not designed to find truth.

It was designed to maintain racial hierarchy and white supremacy.

Thomas’s journal showed his desperate attempts to save Daniel.

He hired an attorney from Memphis, one of the few lawyers willing to defend black clients.

He gathered statements from people who could testify to Daniel’s good character.

He documented the timeline of events showing that Daniel couldn’t have been at the Garrett property when the theft allegedly occurred.

But none of it mattered.

The trial was scheduled for July 28th, and everyone knew the outcome was predetermined.

Dr.

Patterson found the most painful entries in Thomas Brennan’s journal in the days leading up to and immediately after Daniel’s trial.

These entries revealed the impossible choice Thomas faced.

A choice between his principles and his survival, between his friend and his own life.

July 26th, 1899.

I have been warned by multiple people not to testify on Daniel’s behalf.

Yesterday, three men came to my property at night.

They did not identify themselves, but their message was clear.

If I testify, my farm will be burned and I will be driven out or worse.

They called me r lover and traitor and said I had lived here too long thinking my union past would protect me.

They said those days are over and if I don’t remember my place I’ll be reminded of it.

July 27th, 1899.

I cannot sleep.

Tomorrow is the trial.

I’ve spent the entire night wrestling with what I must do.

If I testify honestly, I will tell the court that Daniel is innocent, that Robert Garrett is the actual thief, that this accusation is a lie designed to protect a white man at the expense of an innocent black man.

But if I do this, I will not save Daniel.

The court will not believe me or will not care, and I will be destroyed.

They will burn my farm, perhaps kill me.

I’m an old man with no family, no protection.

I fought for the Union 35 years ago, but that means nothing here now.

I have lived among these people for 30 years, and they have tolerated me only barely.

This will be the end of that tolerance.

July 28th, 1899.

The trial was today.

I attended.

I sat in the courthouse and watched as they brought Daniel in chains.

He looked at me with hope in his eyes.

He believed I would save him.

The prosecutor presented the evidence, the jewelry found in Daniel’s cabin.

Mrs.

Garrett’s testimony about the theft.

Robert’s testimony claiming he saw Daniel near their property on the day of the theft.

All lies.

All carefully constructed lies.

Then the defense attorney called me to testify.

I stood up.

I walked to the front of the courtroom.

Every white person there was staring at me with hatred.

I could feel it.

The judge asked me to testify to Daniel’s character.

I opened my mouth and I heard myself say words I will never forgive.

Daniel Freeman worked for me for 6 years.

He was a reliable worker.

I cannot speak to his activities outside my property.

I do not know what he may have done elsewhere.

That was all.

I did not defend him.

I did not tell the truth about Robert Garrett.

I gave testimony so weak, so meaningless that it helped no one.

The judge thanked me and dismissed me.

I sat down.

I could not look at Daniel.

I could not bear to see his face.

The trial had lasted less than 2 hours.

Daniel was convicted and sentenced to 10 years of hard labor in the state penitentiary, effectively a death sentence, as conditions in Mississippi prisons were notoriously brutal and mortality rates were extremely high, especially for black prisoners.

Thomas’s journal entry from that evening was barely legible, the handwriting shaky.

Daniel was taken away in chains.

As they led him out of the courthouse, he looked at me one last time.

There was no anger in his eyes, only sadness and understanding.

He knew why I had failed him.

He knew I was afraid, and that makes it worse.

I have betrayed the only real friend I have had in decades.

I have betrayed everything I fought for in the war.

I have betrayed my own principles.

And for what? To save my farm? To save my life? What good is a life built on such betrayal? Dr.

Patterson traced what happened to Daniel after his conviction, and the records told a grim story.

Daniel was sent to the Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman, which operated as a plantation using convict labor, a system that essentially reinsslaved black men through the criminal justice system.

Prison records showed that Daniel Freeman, prisoner Mars 3847, arrived at Parchman on August 3rd, 1899.

He was assigned to work in the cotton fields.

The conditions at Parchman were notoriously brutal.

Prisoners worked from dawn to dusk in the Mississippi heat, were housed in overcrowded and unsanitary barracks, received inadequate food and medical care, and were subjected to violent punishment for any perceived infractions.

Daniel survived barely 7 months.

Prison death records showed that Daniel Freeman died on March 4th, 1900.

Cause of death was listed as pneumonia, but Patterson knew that pneumonia was often used as a catch-all diagnosis for deaths resulting from malnutrition, exhaustion, untreated injuries, or violence.

Daniel was 22 years old.

His body was buried in the prison cemetery, an unmarked grave among hundreds of others, mostly black men who had been convicted of minor or fabricated offenses, and worked to death in what was slavery by another name.

Thomas Brennan’s journal entries from this period showed a man consumed by guilt and grief.

When he learned of Daniel’s death in March 1900, he wrote, “Daniel is dead.

They sent me a brief notification.

Prisoner Nar 3847, deceased, effects to be disposed of.

” As if he were nothing.

as if his life meant nothing.

He died in that hellish place because I did not have the courage to save him.

I stood in that courtroom and I chose my own safety over his life.

I chose wrong.

I have been choosing wrong my entire time in this cursed place.

What was the point of fighting in the war if I surrendered my principles the moment they were truly tested? Thomas stopped farming after Daniel’s death.

His property records showed that the farm fell into disrepair.

He sold most of his land in 1901, keeping only a few acres in a small house.

Tax records indicated he lived in poverty for his remaining years, apparently unable or unwilling to work.

Patterson found one more crucial document, a letter Thomas had written in 1902, but apparently never sent.

It was addressed to Daniel’s mother’s sister, a woman named Rebecca, who lived in Memphis.

Thomas had tried to locate Daniel’s family after his death.

Dear Mrs.

Rebecca, I do not know if you remember me, but I employed your nephew, Daniel Freeman, for 6 years on my farm in Tallahassee County.

I am writing to tell you that Daniel died in March 1900 in the state prison where he was sent after being falsely convicted of theft.

I am writing to tell you that I failed him.

I could have testified to his innocence.

I could have fought harder to defend him.

I did not.

I was afraid of what they would do to me if I stood up for a black man against white accusers.

So I remained silent and Daniel went to prison and now he is dead.

I am writing to tell you this because someone should know the truth.

Someone should know that Daniel was innocent.

that he was a good young man who deserved better than what this world gave him.

I am writing to ask for your forgiveness, though I do not deserve it and do not expect it.

I’m writing because I cannot live with this guilt in silence anymore.

” The letter had never been sent.

Perhaps Thomas had lost his courage again.

Perhaps he couldn’t bear to face Daniel’s family.

The letter remained in his papers, a confession that would not be read until Patterson found it 117 years later.

Dr.

Patterson traced Thomas Brennan’s life through his final years, and it was a portrait of a man haunted by his failure.

Census records from 1900 and 1910 showed Thomas living alone in increasingly impoverished circumstances.

Neighbors accounts found in local history collections described him as a recluse who rarely spoke to anyone and seemed to be punishing himself through isolation.

In 1903, Thomas had added those final words to the back of the photograph.

It did not.

God forgive me.

The photograph itself, which should have been a celebration of an unlikely friendship, had become a memorial to betrayal and loss.

Thomas kept it displayed in his home, according to one account from a minister who visited him in 1904, as if he were forcing himself to remember his shame.

Thomas had also written extensively in his journal during these years, entries that revealed a man tormented by guilt and consumed by questions of moral courage.

One entry from 1904 read, “I have been thinking about what courage means.

During the war, I thought I was brave.

I faced bullets.

I charged into battle.

I was wounded twice and kept fighting.

But that was easy courage.

The courage that comes from being surrounded by other soldiers, from following orders, from having clear enemies and clear objectives.

Real courage is different.

Real courage is standing alone against your own community, risking everything with no army behind you and no certainty of victory.

That is the courage I lacked when Daniel needed me.

Another entry from 1906.

I tell myself that I could not have saved him.

that even if I had testified fully and honestly, the court would have convicted him anyway.

I tell myself that sacrificing myself would have been pointless.

But I know these are lies I tell to make the guilt more bearable.

The truth is simpler and more terrible.

I was afraid.

I chose my own safety over my friend’s life.

I chose my farm over his freedom.

And now he is dead and I am alive.

And what good has that done? The farm is failing.

I barely eat.

I barely sleep.

I’m alive in body but dead in every way that matters.

Patterson found evidence that Thomas had tried in small ways to make amends.

He had donated money anonymously to the African Methodist Episcopal Church where Daniel had attended.

He had left food and supplies on the doorsteps of black families in the area.

But these acts of penance were anonymous and inadequate.

And Thomas knew it.

The most revealing entries came from 1907 when Thomas had apparently decided to write a full confession of what had happened, intending to send it to newspapers or perhaps to civil rights organizations in the north.

He wrote dozens of pages detailing Daniel’s false accusation, Robert Garrett’s actual guilt, the threats Thomas had received, and his own failure to act courageously, but the confession was never sent.

The last entry about it read, “I have written it all down.

The full truth of what happened to Daniel, but what good will it do now? He is dead.

Robert Garrett is still free and unpunished.

The system that destroyed Daniel continues to destroy others.

My confession will change nothing.

It will only confirm what everyone already knows, that justice is a lie in this place and that I am a coward who let his friend die.

Thomas Brennan died in January 1910 at age 78.

His death certificate listed cause of death as heart failure, but Patterson suspected it was more accurate to say he died of a broken heart and a crushed spirit.

He left no will, no heirs, no estate of any value.

His few possessions, including the photograph of himself and Daniel, were sold at auction to pay his burial expenses.

Dr.

Patterson knew he needed to verify Thomas’s account of what had happened.

Had Daniel truly been innocent? Had Robert Garrett been the actual thief? Patterson began investigating the Garrett family, searching for any evidence that would corroborate or contradict Thomas’ journal entries.

He found Robert Garrett’s trail through historical records.

Robert had continued living in Charleston, Mississippi through the early 1900s.

He never held steady employment, according to city directories, but lived on family money.

In 1902, he was arrested for assault following a barroom fight, but was never prosecuted.

The charges were quietly dropped.

In 1904, he was sued by creditors for gambling debts totaling over $800, a substantial sum.

Then, Patterson found something crucial, a confession.

In 1908, Robert Garrett had been arrested for theft after being caught trying to sell stolen jewelry in Memphis.

During questioning, apparently while intoxicated, he had admitted to previous thefts, including stealing from his own mother years before.

A Memphis police report filed away in city archives contained a detective’s notes.

Subject admitted to stealing jewelry from his mother’s home in approximately 1899 states he blamed a negro servant to avoid consequences.

Appeared to find this amusing.

The report confirmed everything Thomas had written.

Daniel had been innocent.

Robert had stolen from his own mother, framed Daniel, and watched as an innocent young man was sent to prison to die.

All to protect himself from the consequences of his own crimes.

and the legal system had been happy to accept this narrative because it aligned with their prejudices and their need to maintain racial hierarchy.

Patterson also found evidence about what had happened to the stolen jewelry.

The same Memphis police report noted that Robert had sold his mother’s jewelry to pay gambling debts in 1899.

The items supposedly found in Daniel’s cabin had been different pieces, cheap imitations that Robert had planted there to frame Daniel.

Mrs.

Garrett had been too distraught or too willing to believe her son to notice the substitution.

Patterson traced Robert Garrett’s life forward.

After his arrest in Memphis, he apparently left Mississippi to avoid further legal troubles.

He appeared in census records in New Orleans in 1910, listed as a salesman with no fixed address.

He died in 1917 in a charity hospital in New Orleans, penniless and alone, his death notice mentioning no family or friends.

He was 42 years old.

The contrast was striking.

Daniel, innocent and hardworking, had died at 22 in a prison where he should never have been sent.

Robert, guilty and destructive, had lived to 42, never truly punished for his crimes.

The injustice was complete and absolute.

Patterson also tried to trace Daniel’s family.

He found that Rebecca, Daniel’s aunt, whom Thomas had tried to contact, had left Mississippi in 1903, joining the great migration of black Americans, leaving the South for opportunities in northern cities.

Census records showed her in Chicago in 1910, working as a seamstress and living with her husband and three children.

She died in 1932 at age 74.

Through genealological databases, Patterson located Rebecca’s descendants, her great great-granddaughter, a woman named Angela Turner, living in Chicago.

He contacted her, explaining his research and sharing what he had learned about Daniel’s fate.

Angela had heard family stories about an uncle who had died young in Mississippi, but no details had survived.

The family had believed he died in some kind of accident.

They had never known the full truth.

In November 2019, Dr.

Patterson published his findings in a detailed article for the Journal of Southern History.

The article included the photograph of Thomas and Daniel, reproductions of Thomas’s journal entries, evidence of Daniel’s innocence, and documentation of Robert Garrett’s confession.

The article was titled The Cost of Silence: Friendship, Betrayal, and Injustice in Post Reconstruction, Mississippi.

The response was immediate and powerful.

The story resonated with people because it contained no easy heroes or simple villains.

Thomas Brennan had genuinely cared for Daniel, had believed in racial equality, had tried to live according to his principles.

But when his courage was truly tested, when standing up for those principles meant risking everything, he had failed.

His failure was human, understandable, and unforgivable.

Angela Turner, Daniel’s descendant, traveled to Mississippi with Dr.

Patterson to visit the places where Daniel had lived and died.

They went to the site of Thomas’s farm, now disappeared beneath commercial development.

They visited the courthouse where Daniel had been convicted, still standing and still in use.

They went to Parchman Prison where Daniel had died and stood at the edge of the old convict cemetery where he was buried in an unmarked grave among hundreds of others.

At Angela’s request, Patterson helped arrange for a memorial marker to be placed at the cemetery.

The marker read, “In memory of Daniel Freeman, 1877 1900, and the countless others who died here, convicted by injustice, killed by cruelty, buried in unmarked graves, never forgotten.

” The dedication ceremony in March 2020 was attended by descendants of other prisoners who had died at Parchman, by historians, by community activists, and by people who simply wanted to bear witness to this history.

Angela spoke about Daniel.

He was 22 years old when he died.

He had his whole life ahead of him.

He was guilty of nothing except being black in a place and time where that alone was enough to destroy him.

He deserved justice.

He deserved friendship that didn’t fail when tested.

He deserved to live.

This marker won’t bring him back, but it says his name.

It says he mattered.

It says we remember.

Patterson spoke about Thomas Brennan.

Thomas’ story is not one we want to tell ourselves.

We prefer stories of courage of people who stood up against injustice regardless of the cost.

Thomas’ story is about failure, about a man who knew what was right, who wanted to do what was right, but who ultimately chose his own safety over his friend’s life.

His story is important precisely because it’s uncomfortable.

How many of us, if we’re honest, would have done differently? How many of us would truly risk everything? Our homes, our safety, our lives to stand up for what’s right? Thomas’s failure is a mirror.

It asks us to examine our own courage, our own principles, and whether we would hold to them when truly tested.

The photograph of Thomas and Daniel was displayed at the ceremony, enlarged to poster size.

Seeing the two men standing together in Thomas’s parlor, Thomas’s hand on Daniel’s shoulder, both men smiling with genuine warmth, made the tragedy more painful.

This had been real.

Their friendship had been real.

The betrayal had been real.

The photograph preserved that moment in April 1899 when Thomas still believed he would be brave enough to protect his friend if the time came.

It was evidence of both the possibility of human connection across the barriers of race and the fragility of that connection when subjected to the pressures of white supremacist violence.

The inscription on the back of the photograph, “May this friendship endure,” followed by, “It did not, God forgive me,” became a focal point of discussion.

Some argued that Thomas deserved some measure of forgiveness or understanding given the extreme danger he faced.

Others argued that moral courage means doing the right thing precisely when it’s dangerous, and that Thomas’s failure cost Daniel his life.

Patterson believed both perspectives had merit.

Thomas’s fear was understandable, but understanding does not equal excusing.

Daniel had died because Thomas chose silence.

The photograph itself, now preserved in the University of Mississippi archives, became part of exhibitions about race relations in the postreonstruction south.

It traveled to museums in Jackson, Atlanta, Memphis, and Chicago.

Each time it was displayed, it sparked conversations about friendship, courage, betrayal, complicity, and the everyday choices that sustain or challenge systems of injustice.

Angela Turner kept a copy of the photograph in her home in Chicago.

She had it framed alongside the only other image she had of Daniel, his prison intake photograph from Parchman, where he looked gaunt and terrified.

A young man who knew he had been condemned to death by a legal system designed to destroy people like him.

The contrast between the two photographs told the complete story.

Daniel and Thomas’s home, safe and smiling, believing in the friendship that connected them, and Daniel in prison, abandoned and doomed, the friendship having failed when he needed it most.

Patterson continued his research, finding other stories of friendships across racial lines in the postreonstruction south.

Friendships that had survived against all odds, and friendships that had crumbled under pressure.

Each story was unique, but they shared common elements.

The extraordinary courage required to maintain such friendships in a society built on racial separation and hierarchy, and the terrible cost when courage failed.

The photograph of Thomas and Daniel, taken in that parlor in April 1899, remained what it had always been, evidence.

Evidence of genuine human connection.

Evidence of Thomas’s principles and Daniel’s trust.

An evidence of the moment before everything fell apart.

A moment preserved forever.

A moment that asked everyone who saw it to consider what they would have done, whether they would have been brave enough, whether their friendship would have endured when tested by violence and fear.

On the back of the photograph, Thomas’s anguished words remained.

It did not.

God forgive me.

Whether God had forgiven him, no one could say.

But the photograph ensured that neither Thomas’s friendship with Daniel nor his failure to protect Daniel would be forgotten.

The image stood as testament to both the possibility of human connection across the barriers erected by racism and the fragility of that connection in the face of systemic violence.

It was a story without redemption, without comfort, without easy lessons, only the painful truth that sometimes friendship is not enough.

Sometimes courage fails.

Sometimes people we trust make choices that destroy us.

And sometimes all that remains is a photograph in the terrible knowledge of what might have been.

News

This 1898 Photograph Hides a Detail Historians Completely Missed — Until Now, and What They Found Has Them Questioning Everything 📸 — For decades it gathered dust in a quiet archive, labeled “ordinary,” dismissed as just another stiff Victorian snapshot, until a high-resolution scan exposed one tiny, impossible detail lurking in the background, and suddenly the smiles looked fake, the poses suspicious, and experts realized they weren’t staring at a memory… they were staring at a secret frozen in time 👇

This 1888 photograph hides a detail historians completely missed until now. The basement archives of the Charleston County Historical Society…

This Portrait of Two Friends Seemed Harmless — Until Historians Spotted a Forbidden Symbol Hidden Between Them and Everything Fell Apart ⚠️ — At first it was just two smiling companions shoulder-to-shoulder in stiff old-fashioned suits, the kind of wholesome image you’d frame without a second thought, but a closer scan revealed a tiny, outlawed mark tucked into the shadows, and suddenly the photo wasn’t friendship… it was rebellion, secrecy, and a message never meant to survive the century 👇

This portrait of two friends seemed harmless until historians noticed a forbidden symbol. The afternoon sun filtered through the tall…

Experts Thought This 1910 Studio Photo Was Peaceful — Until They Zoomed In and Saw What the Girl Was Holding, and the Entire Room Went Cold 📸 — At first it looked like another gentle Edwardian portrait, lace dress, soft lighting, polite smile, but when archivists enhanced the image they noticed her tiny fingers clutching something oddly deliberate, something that didn’t belong in a child’s hands, and suddenly the sweetness curdled into dread as historians realized this wasn’t innocence… it was a clue 👇

Experts thought this 1910 studio photo was peaceful until they saw what the girl was holding. Dr.Maya Johnson’s hands trembled…

This Portrait from 1895 Holds a Secret Historians Could Never Explain — Until Now It’s Finally Been Exposed in Stunning Detail 🖼️ — For more than a century it hung quietly in dusty archives, dismissed as another stiff Victorian pose, until a routine scan revealed a tiny, impossible detail that made experts freeze mid-sentence, because suddenly the calm expressions looked staged, the shadows suspicious, and the entire image felt less like art… and more like evidence 👇

The fluorescent lights of Carter and Sons estate auctions in Richmond, Virginia, cast harsh shadows across tables piled with forgotten…

It Was Just a Studio Photo — Until Experts Zoomed In and Saw What the Parents Were Hiding in Their Hands, and the Room Went Dead Silent 📸 — At first it looked like another stiff, sepia family portrait, the kind you pass without a second thought, but when historians enhanced the image and spotted the tiny, deliberate objects clutched tight against their palms, the smiles suddenly felt forced, the pose suspicious, and the entire photograph transformed from wholesome keepsake into something deeply unsettling 👇

The auction house in Boston smelled of old paper and varnished wood. Dr.Elizabeth Morgan had spent the better part of…

This Forgotten 1912 Portrait Reveals a Truth That Changes Everything We Thought We Knew — and Historians Are Panicking Over What’s Hidden in Plain Sight 🖼️ — It hung unnoticed for over a century, dismissed as polite nostalgia, until one sharp-eyed researcher zoomed in and felt their stomach drop, because the face, the object, the posture all scream a secret no one was supposed to catch, turning a dusty archive into a ticking historical bombshell 👇

This forgotten 1912 portrait reveals a truth that changes everything we knew until now. Dr.Marcus Webb had been working as…

End of content

No more pages to load