It was just a lost photo from 1923, but it revealed a mystery that has intrigued photographers.

John Allen had spent most of his Saturday mornings for the past 15 years wandering through flea markets and antique shops across Chicago.

At 58, he’d made a comfortable living as a freelance photography restoration specialist.

And his reputation for bringing damaged historical images back to life had earned him clients from museums, universities, and private collectors across the country.

This particular Saturday in late April felt no different from countless others.

He’d already visited three locations, finding nothing of particular interest.

The usual assortment of mass-produced prints, damaged tint types, and overpriced cabinet cards that dealers mistakenly believed were valuable simply because they were old.

The fourth shop was a cramped storefront on the city’s southside, wedged between a pawn shop and a closed restaurant.

The handpainted sign above the door read, “Turner’s Treasures, Antiques, and Curiosities.

” John had never been inside before, though he’d driven past it dozens of times.

A bell chimed as he pushed open the door.

The interior was dim, crowded with mismatched furniture, boxes of books, kitchen implements, and the accumulated debris of forgotten lives.

An elderly man sat behind a cluttered counter, reading a newspaper through thick glasses.

“Help you find something?” the man asked without looking up.

“Just browsing,” John replied, moving toward a section where framed photographs hung haphazardly on the wall.

“Most were unremarkable.

studio portraits from the 1940s and50s, a few family snapshots, several wedding photos with that distinctive post-war aesthetic.

Then something caught his eye.

Partially hidden behind a garish landscape painting was a photograph in an ornate silver frame, tarnished black with age.

John carefully lifted it from its hook and carried it toward the window where natural light could illuminate it properly.

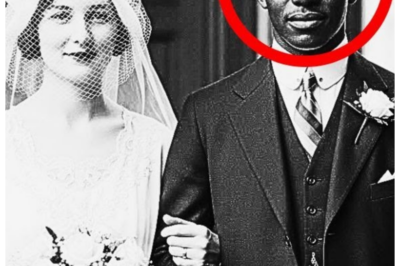

The photograph showed a wedding couple, formal and elegant, standing in what appeared to be a church.

The image quality was remarkable for its age.

sharp focus, excellent tonal range, professional composition.

The bride wore an elaborate white gown with intricate beading, her veil held in place by a delicate crown.

She held a bouquet of what looked like roses and liies.

Her expression was serene, almost ethereal.

The groom stood beside her in a well-tailored dark suit, his posture straight and proud.

His hand rested gently on her waist in the formal manner of the era.

His face showed a slight smile, restrained but genuine.

What struck John immediately was the technical quality of the photograph.

This wasn’t the work of an amateur.

The lighting was sophisticated, the composition carefully planned, the development and printing executed with professional skill.

He turned the frame over carefully.

On the backing written in faded ink was a notation, Marie and Thomas, St.

Louis Cathedral, New Orleans, June 16th, 1923.

John’s pulse quickened slightly.

New Orleans, 1923.

The height of the jazz age.

The cultural renaissance of the city.

A time of profound social change and equally profound resistance to that change.

He carried the photograph to the counter.

How much for this? The elderly man glanced at it without much interest.

Frames probably worth more than the picture.

Silver plate looks like $40.

John paid without haggling, wrapping the frame carefully in newspaper the shopkeeper provided.

As he walked back to his car, he couldn’t shake the feeling that there was something unusual about the photograph, something beyond its technical excellence that he couldn’t quite identify.

That evening, in his home studio, he would begin to discover exactly what that something was.

John’s home studio occupied the entire third floor of his brownstone apartment building.

The space was equipped with everything he needed for his restoration work.

Highresolution scanners, calibrated monitors, specialized lighting equipment, and an extensive library of reference materials on historical photographic processes.

He carefully removed the wedding photograph from its tarnished frame, noting that the image had been professionally mounted on heavy archival board.

The photograph itself appeared to be a gelatin silver print, common for professional studio work in the 1920s.

Under magnification, the image quality was even more impressive than he’d initially observed.

The photographer had used sophisticated lighting, probably a combination of natural light from church windows and carefully positioned artificial sources to create depth and dimension that brought the couple almost to life.

John placed the photograph on his scanner, a specialized device capable of capturing images at extremely high resolution.

As the scan progressed, he watched the monitor as details invisible to the naked eye began to emerge.

The bride’s features were delicate, her skin rendered in smooth tones that suggested careful exposure and development.

Her eyes gazed slightly away from the camera, giving her an air of quiet contemplation.

The groom looked directly at the lens, his expression composed, but with a hint of something Jon couldn’t quite name.

Pride perhaps, or defiance, or maybe just the natural tension of someone being photographed.

John began his standard technical analysis, examining the photograph for signs of damage, fading, or manipulation.

The image was in remarkable condition for its age.

Minimal fading, no significant tears or creases, well preserved despite being nearly a century old.

Then he noticed something unusual.

The tonal range in the groom’s face seemed inconsistent with the lighting.

Jon zoomed in on the facial features, examining the skin texture with professional scrutiny.

He adjusted the contrast and brightness, isolating different tonal ranges.

That’s when he saw it.

Subtle variations in the skin texture, barely visible, but definitely present.

The foundation of the image was slightly different in certain areas, as if the subject’s natural skin tone had been carefully obscured.

John had restored thousands of historical photographs.

He knew the limitations of 1920s photographic technology, understood how different skin tones rendered on orthocchromatic film, recognized the signs of retouching and manipulation common in professional portraiture of the era.

But this was different.

This wasn’t simple retouching to smooth blemishes or soften wrinkles.

This was systematic, careful alteration of skin tone throughout the entire face and visible hands.

He pulled up reference images from his digital library, examples of how different racial characteristics appeared in photographs from the 1920s, particularly those using ortho chromatic film stock, which was highly sensitive to certain wavelengths of light and rendered skin tones and characteristic ways.

The more he examined the groom’s image, the more convinced he became that something had been deliberately concealed.

The bone structure, the subtle texture variations, the way light interacted with certain facial planes, all suggested that the groom’s actual appearance had been carefully modified, either through makeup before the photograph was taken, through manipulation during the printing process, or most likely through a combination of both.

Jon sat back in his chair, his mind racing.

If his analysis was correct, the groom in this 1923 New Orleans wedding photograph was not what he appeared to be.

The technical evidence suggested that he was a black man of relatively light complexion who had been photographed in such a way as to appear white.

In 1923, New Orleans, such deception would have been necessary for one reason only, to circumvent Louisiana’s anti-misogenation laws that made interracial marriage a criminal offense.

The couple in this photograph had committed a crime simply by loving each other.

John spent the next several days immersing himself in research about New Orleans in 1923 and the legal and social structures that governed racial classification and marriage in Louisiana during that period.

What he discovered was both fascinating and deeply disturbing.

Louisiana had some of the most rigid and complex racial classification laws in the United States.

The state’s obsession with racial categorization had produced an elaborate system that classified people not simply as white or colored, but according to precise fractions of African ancestry.

Under Louisiana law, anyone with even one drop of African blood could be classified as black.

Though the actual enforcement of this standard varied depending on social class, economic status, and personal connections, anti-misogenation laws had been enacted during reconstruction and strengthened in the decades that followed.

By 1923, marriage between white and black individuals was not only prohibited, but criminalized.

Violators could face imprisonment, and any children from such unions were considered illegitimate with no legal rights to inheritance or family name.

But Louisiana’s complex racial history had created an unusual situation.

The state had a significant population of mixed race individuals.

Many descended from relationships during the French and Spanish colonial periods.

These people, often called creoles of color, occupied an ambiguous social space.

And some, particularly those with very light complexions, engaged in what was known as passing, living as white to escape the brutal restrictions and violence of Jim Crow segregation.

Passing was dangerous.

Discovery could mean loss of employment, social ostracism, violence, or arrest.

Families who passed lived in constant fear that some physical characteristic, some slip of speech, some encounter with someone from their past would reveal their secret and destroy everything they’d built.

John found records of prosecutions under Louisiana’s anti-misogenation statutes.

In 1924, just a year after the wedding photograph was taken, a New Orleans couple had been arrested and imprisoned when an anonymous tip revealed that the husband, who had been living as white, had African ancestry.

The wife, who genuinely hadn’t known about her husband’s background, was publicly humiliated.

Their children were removed from white schools.

The family was destroyed.

The more John researched, the more he understood the courage and the terror that the couple in the photograph must have experienced.

Getting married in St.

Louis Cathedral, one of the most prominent churches in New Orleans, was an audacious act.

It meant maintaining the deception, not just privately, but publicly in front of witnesses, before a priest, creating legal documents that could be scrutinized.

The notation on the back of the photograph, Marie and Thomas, provided limited information.

These were common names, and without surnames, tracing them through historical records would be nearly impossible.

Church marriage records from St.

Louis Cathedral in 1923 might still exist, but accessing them would require permission and cooperation from the arch dascese.

John also researched the photographic studios operating in New Orleans during that period.

There were dozens ranging from prestigious establishments serving wealthy clients to modest operations working with middle-class families.

The technical quality of the wedding photograph suggested a skilled professional, someone with access to good equipment and significant expertise.

He examined this photograph again, looking for any identifying marks, a photographer’s stamp, a studio name, anything that might provide a lead.

There, embossed very faintly in the lower right corner, he found what he was looking for.

Bumont Studio, New Orleans.

A quick search revealed that Bowmont Studio had been a respected photography business operating in the French Quarter from 1919 until 1943 when the owner retired.

Some of the studios records had been donated to the New Orleans Public Libraries Louisiana Division.

John booked a flight to New Orleans for the following week.

New Orleans in late spring was already humid, the air thick with the scent of magnolia and the promise of summerstorms.

John arrived in the early afternoon and checked into a modest hotel in the French Quarter close to both the library and St.

Louis Cathedral.

The Louisiana division of the New Orleans Public Library occupied a climate controlled room on the second floor.

Its walls lined with archival boxes and its tables populated by researchers examining old documents with careful intensity.

The librarian, a woman named Patricia Landry, who appeared to be in her 60s, greeted John warmly when he explained his research interest.

Bumont Studio, she said thoughtfully.

We have some of their business records, though they’re not complete.

The owner’s daughter donated them in the 1970s, but unfortunately a lot was lost over the years.

Water damage, deterioration, simple neglect.

She led him to a table and brought out three archival boxes.

These contain ledgers, correspondence, some sample photographs, and miscellaneous business records.

You’re welcome to examine everything, but please use the cotton gloves and handle the materials carefully.

John spent the next 4 hours going through the boxes methodically.

The ledgers showed a thriving business, portraits, weddings, commercial photography for local businesses.

The entries were meticulous, listing client names, dates, services provided, and payments received.

He found the entries for June 1923, and began reading carefully.

There were dozens of weddings photographed that month.

New Orleans was a popular location for summer ceremonies despite the heat.

On June 16th, the date written on the back of his photograph, there were three weddings listed.

The third entry made his breath catch.

Wedding portrait, Thomas Lauron and Marie Devo.

St.

Louis Cathedral.

Full formal package.

Payment 45 million hours.

Balance paid.

Thomas Laurent and Marie Devo.

Now he had full names.

But there was something else in the entry.

A small notation in different ink apparently added later.

Special handling per client request.

Extra care with lighting and development.

John understood immediately what special handling meant.

The photographer had been complicit in the deception, had understood exactly what was needed, and had used his professional skills to help the couple pass.

Patricia noticed Jon’s intense focus on the ledger.

“Did you find something interesting?” “I found the couple I’m researching,” John replied.

“Thomas Laurent and Marie Devo, married June 16th, 1923.

Do you have any other records that might mention them? City directories, census records, anything?” Patricia pulled up the library’s database on her computer.

Laurent is a common name in New Orleans, especially among the Creole population.

Let me search for Thomas Laurent, born around, let’s say, 1890 to 1905, to get the right age range for someone marrying in 1923.

The search returned multiple results.

Patricia narrowed it down by checking the 1920 census records for New Orleans.

Here, she said, turning the monitor so John could see.

Thomas Laurent, born 1898, listed as mulatto in the 1920 census.

occupation musician lives in the Tmaine neighborhood.

The Tmaine neighborhood had been the heart of New Orleans free black community since before the Civil War.

It was also the birthplace of jazz, home to musicians, artists, and a vibrant cultural community.

And Marie Devo, John asked.

Patricia searched again.

Marie Devo, born 1902, listed as white in the 1920 census, lives on Esplanade Avenue with her parents.

Father is listed as a merchant.

John sat back absorbing the information.

Thomas Lauron, a black musician from TMA.

Marie Dero, a white woman from a merchant-class family.

Somehow they had met, fallen in love, and found a way to marry despite laws designed specifically to prevent such unions.

The courage that required was almost incomprehensible.

St.

Louis Cathedral stood as it had for centuries, its distinctive spires dominating Jackson Square.

John approached the building with a mixture of reverence and nervousness, carrying a folder with copies of the photograph and the information he’d gathered from the library.

The cathedral office was located in a building adjacent to the main church.

John explained his research to the receptionist who directed him to Father Michael Tibido, a priest in his 70s who served as the cathedral’s unofficial historian.

Father Tibido received John in a small office crowded with books and files.

He was a gentleman with white hair and kind eyes that suggested he’d heard many stories and judged few of them.

You’re researching a marriage that took place here in 1923? Father Tibido asked after John explained his visit.

Yes, Thomas Laurent and Marie Devo.

June 16th, 1923.

I have reason to believe there were unusual circumstances surrounding the marriage.

Father Tibido studied John carefully.

What kind of unusual circumstances? John decided on honesty.

I believe Thomas Lauron was a black man who was passing as white in order to marry Marie Devou, who was white.

I believe the photographer who took their wedding portrait helped conceal Thomas’ racial identity through careful lighting and processing.

The priest was quiet for a long moment.

That would have been illegal at the time, a violation of Louisiana’s anti-misogenation laws.

The marriage would have been void and both parties could have faced criminal prosecution.

I know, but I also believe this photograph represents an act of extraordinary courage and love.

I’m trying to understand their story to find out what happened to them.

Father Tibido rose and walked to a filing cabinet.

Our marriage records from that era are complete.

They’re also confidential technically, though after 100 years, I think we can make an exception in the interest of historical understanding.

He pulled out a thick ledger and turned pages until he found the entry he was looking for here.

Lauron Ende June 16th, 1923.

Officiated by Father Antoine Rouso, who died in 1956.

Witnesses Marcel Fontau and Josephine Duma.

marriage license number?” He read off a series of numbers.

“Is there anything unusual in the record?” John asked.

“Nothing obvious.

The marriage appears to have been conducted in the standard manner, but Father Tibido paused.

Father Rouso kept personal diaries.

They’re in our archives.

I’ve read some of them while researching cathedral history.

” He was a thoughtful man, troubled by many of the injustices he witnessed.

Would it be possible to see the diary entries from June 1923? Father Tibido considered the request.

normally no, but given the historical significance and the fact that all parties involved have been deceased for many years, I think we can make an exception.

Wait here.

He returned 20 minutes later with a leatherbound journal, its pages yellowed but still legible.

June 1923, he said, opening to the relevant section.

Father Rouso wrote regularly, almost daily.

John read the entry dated June 16th, 1923.

Today, I performed a marriage ceremony that troubles my conscience, even as it fills my heart with admiration.

The couple came to me three months ago requesting that I marry them.

The young man is clearly of mixed race, though he presents himself to the world as white.

The young woman is genuinely white from a respectable merchant family, though her parents have disowned her for her choice.

They understand the law forbids their union.

They understand the dangers.

But they also understand something that our laws do not.

that love recognizes no color, that the soul knows no race, that God’s love extends to all his children regardless of the divisions humans create.

I struggled with this decision.

To perform this marriage is to violate the law of the state.

But to refuse is to deny the grace of the sacrament to two people whose love is genuine and whose commitment to each other is absolute.

I chose love over law.

I chose God’s commandment to love one another over human laws designed to keep people apart.

May God forgive me if I have erred, but I believe I must believe that love is never a sin, even when the law declares it criminal.

Armed with the full names and the marriage record, John returned to the New Orleans Public Library to search for what happened to Thomas and Marie after their wedding.

What he discovered was both frustrating and telling.

The historical trail essentially disappeared after 1923.

The 1930 census, which should have listed the couple if they remained in New Orleans, showed no record of Thomas Laurent and Marie Devo, either separately or together.

City directories from the mid to late 1920s likewise showed no listings.

It was as if they had simply vanished.

John expanded his search to surrounding parishes and to other Louisiana cities, thinking perhaps they had relocated to maintain their deception.

Nothing.

He searched death records, thinking perhaps tragedy had struck early.

Still nothing.

Patricia Landry, the librarian who had been helping John with his research, offered a theory.

If they were discovered, or if they feared discovery was imminent, they might have left Louisiana entirely.

Passing was easier in places where no one knew your history.

Northern cities, Chicago, Detroit, New York, had large populations and more anonymity.

John considered this.

But wouldn’t there be some record of their departure, property sales, forwarding addresses, something? Not necessarily.

If they left quickly and quietly to avoid prosecution or violence, they might have simply abandoned everything.

It happened more often than you’d think.

People would disappear in the night, leaving behind homes, possessions, entire lives just to survive.

The research was leading to a difficult conclusion.

Whatever had happened to Thomas and Marie Lauron, it hadn’t been good.

People who left comfortable lives and disappeared from all records were usually running from something terrible.

John decided to search newspaper archives, hoping to find some mention of the couple.

New Orleans newspapers from the 1920s were available on microfilm.

And he spent two long days scrolling through page after page, searching for any reference to Thomas Lauron, Marie Dearu, or even the surname Laurent in connection with any scandal or prosecution.

On the third day, he found something.

A small article buried on page 8 of the New Orleans Times Pikaune dated November 3rd, 1941, 18 years after the wedding.

Anonymous tip leads to investigation of fraudulent marriage.

The article was brief and deliberately vague, as was common for such stories during that era.

Local authorities are investigating claims that a marriage performed in the city in the early 1920s may have violated Louisiana’s racial integrity laws.

An anonymous source has provided information suggesting that one party to the marriage misrepresented their racial status.

The couple in question reportedly left New Orleans many years ago, and their current whereabouts are unknown.

District Attorney’s office declined to comment on whether charges will be filed.

November 1941.

John noted the date carefully.

The article suggested that someone, perhaps a former neighbor, a business rival, or someone with a personal grudge, had reported the couple nearly two decades after their wedding.

By 1941, Thomas and Marie would have been in their 40s.

They might have had children, built a life somewhere, believed themselves safe after so many years, and then this anonymous accusation had surfaced, threatening everything they’d created.

The article mentioned they had reportedly left New Orleans many years ago, which suggested the authorities had investigated and found no current address, but it also suggested that the threat had been real enough that someone was looking for them.

John searched for follow-up articles, but found nothing.

Either the investigation had been dropped for lack of evidence, or the couple had successfully disappeared so thoroughly that authorities couldn’t locate them.

He sat in the library, surrounded by microfilm reels and photocopies of documents, and felt the weight of their story.

Thomas and Marie had fought for their love, married despite the laws forbidding it, and then spent years, perhaps decades, looking over their shoulders, knowing that discovery could come at any moment.

And in 1941, 18 years after their wedding, someone had tried to destroy them.

Back in Chicago, John couldn’t stop thinking about Thomas and Marie.

The research had become more than a professional project.

It had become a personal mission to understand what had happened to them and to give their story the recognition it deserved.

He returned to the photograph, examining it with fresh eyes and deeper knowledge.

These weren’t just anonymous faces from the past.

This was Thomas Lauron, musician from TMA, and Marie Devro, daughter of a merchant family, two people who had risked everything for love.

John began searching northern city records, focusing on Chicago, given its large black population and its history as a destination for people fleeing southern segregation.

He searched through Chicago city directories from the 1920s and 1930s, looking for any listing of Thomas Lauron or Marie Devaroo.

The problem was that Lauron was a common surname, particularly among French and Creole populations.

There were dozens of Lawrence in Chicago during that period.

Without additional identifying information, finding the right Thomas Lauron would be nearly impossible.

Then John had another idea.

Thomas had been listed as a musician in the 1920 census.

If he had continued working in music, there might be records, union membership, performance listings, recording credits.

Jazz had moved north during the great migration and Chicago had become one of its major centers.

John contacted the Chicago Jazz Archive at the University of Chicago explaining his research.

The archivist, a young woman named Andrea Martinez, was immediately interested.

We have extensive collections related to musicians who migrated from New Orleans, she explained over the phone.

Many of them came north in the 1920s and 30s.

If your Thomas Lauron continued working in music, we might have something.

Two days later, John sat in the archives reading room going through boxes of materials related to New Orleans musicians in Chicago.

There were photographs, performance programs, union records, newspaper clippings, and personal papers donated by musicians families over the years.

In a box of Musicians Union Local 208 Records, the Black Musicians Union in Chicago, John found a membership card that made his heart race.

Thomas Lauron, trumpet, join 1924.

address 3847 South State Street.

One year after the wedding, Thomas had come to Chicago and resumed his musical career, joining the union under his real name.

But there was no mention of Marie.

No spouse listed.

No emergency contact information that would have included her name.

John searched Chicago census records for 1930.

He found Thomas Lauron living at an address on the south side listed as negro occupation musician, but the household composition showed him living alone.

No wife, no children.

Had they separated? Had Marie stayed behind in New Orleans? Or had she been living with him under a different name hidden from official records? John continued searching and found something unexpected, a death certificate.

Marie Deo Lauron died February 18th, 1945, age 43 in Chicago.

Cause of death, pneumonia.

The informant listed on the death certificate was Thomas Lauron, spouse.

So they had stayed together.

Marie had died in Chicago in 1945, and Thomas had been there with her, listed officially as her spouse, despite the laws that had once made their marriage illegal.

John searched for Thomas’s death record, and found it dated 1968.

He had lived to be 70, dying more than two decades after Marie.

The death certificate listed no surviving children, no next of kin except a nephew.

The story was taking shape, but many questions remained.

Had they spent their years in Chicago in fear? Had they maintained the deception about Thomas’s race, or had they lived openly in the black community? What had their life together been like after fleeing New Orleans? The nephew listed in Thomas Laurent’s 1968 death certificate was named Marcus Fontau.

The surname rang a bell.

Fontnau had been one of the witnesses at Thomas and Marie’s 1923 wedding.

Perhaps Marcel Fontineau, the witness, had been Thomas’s brother-in-law or close friend, and Marcus was his son.

Finding Marcus Fontino proved challenging.

The name was common and the man would be quite elderly by now if he was still alive.

John worked through genealological databases and public records tracing the Fontineau family line.

After two weeks of searching, he found a Marcus Fontineau, age 81, living in a retirement community on Chicago’s Southside.

John called the facility and asked to be connected to Mr.

Fontnau’s room.

The voice that answered was weak but alert.

Yes, Mr.

Fontnote.

My name is John Allen.

I’m a historical researcher and I’m trying to learn about your uncle Thomas Lauron.

Would you be willing to speak with me? There was a long pause.

Why are you asking about Uncle Thomas? I discovered a photograph of him and his wife Marie from their wedding in 1923.

I’ve been researching their story, and I’d very much like to understand what their life was like.

Another pause.

That wedding? That photograph? I never thought anyone would find it after all these years.

Can we meet? I’d like to show you what I’ve discovered and hear anything you’re willing to share.

Two days later, John sat in the common room of the retirement community with Marcus Fontinote.

a thin man with kind eyes and hands that trembled slightly from age.

Between them on the table was the wedding photograph along with copies of all the documents Jon had gathered.

Marcus stared at the photograph for a long time, his eyes missing.

I haven’t seen this picture in 60 years, he whispered.

My father was the witness at their wedding.

Marcel want to know.

He was Uncle Thomas’s best friend from New Orleans.

They grew up together in TMA.

What can you tell me about Thomas and Marie? John asked gently.

Marcus took a shaky breath.

Uncle Thomas was one of the best trumpet players in New Orleans.

He could make that horn sing in ways that would break your heart.

He met Maria at a club where he was playing, one of those places in the French Quarter where the races mixed more than they should have if you listen to the law.

He paused, gathering his thoughts.

Marie’s family was respectable.

Merchants, shop owners.

When they found out she was in love with a black musician, they disowned her.

Cut her off completely.

But she didn’t care.

She loved him, and that was all that mattered to her.

They got married in 1923.

John prompted.

But then they disappeared from New Orleans Records.

Marcus nodded.

They stayed in New Orleans for about a year after the wedding.

Uncle Thomas kept playing music and Marie worked as a seamstress.

They were careful.

Very careful.

Uncle Thomas wore makeup when they went out together.

Lightened his skin.

They avoided certain neighborhoods, certain people.

They lived in constant fear, but they were together.

What made them leave? Someone started asking questions.

One of Marie’s relatives saw them together and got suspicious.

Uncle Thomas heard through the musicians network that people were talking that there might be trouble.

So they left, just packed what they could carry and took the train north in the middle of the night.

My father helped them get away.

They came to Chicago.

Yes, the Southside had a big community of people from New Orleans.

Uncle Thomas could work as a musician, and nobody questioned his relationship with Marie because the rules were different up north.

Not perfect.

God knows there was plenty of racism in Chicago, too, but different.

They could be together without hiding as much.

Marcus touched the photograph gently, but they never stopped being afraid.

Even 20, 30 years later, Uncle Thomas would get nervous if someone from New Orleans came through town.

He always worried that someone would remember, would report them, would try to punish them for what they’ done.

The newspaper article from 1941, John said, “Someone did report them.

” Marcus’ face darkened.

That was the worst time.

An anonymous letter sent to authorities in New Orleans claiming that Uncle Thomas had deceived Marie had fraudulently married her.

The New Orleans police contacted Chicago police asking for help locating them.

Uncle Thomas and Aunt Marie had to hire a lawyer, had to prove that their marriage was legal under Illinois law, even if it had been illegal in Louisiana.

It took months before the investigation was dropped, and the stress of it nearly killed Aunt Marie.

She was never the same after that.

Marcus continued his story, his voice growing stronger as memories surfaced.

After the 1941 investigation, Uncle Thomas stopped playing music publicly.

He was too afraid that someone would recognize him, that another accusation would come.

He took a job as a janitor at a school.

Good, honest work, but nothing like the music that had been his life.

John felt the tragedy of that deeply.

A talented musician forced to abandon his art out of fear.

Aunt Marie tried to keep his spirits up.

Marcus said, she would tell him it didn’t matter what he did for work, that they had each other and that was enough.

But I could see it hurt him to give up music.

Sometimes late at night, he’d take out his trumpet and play quietly just for her where nobody else could hear.

“Did they have children?” John asked, though the records had suggested they hadn’t.

Marcus shook his head sadly.

“They wanted to desperately, but they were too afraid.

” Aunt Marie worried that a child might somehow reveal the truth about Uncle Thomas’s background, that questions would be asked, that the secret would come out.

And Uncle Thomas couldn’t bear the thought of bringing a child into a world where they’d have to lie about who their father really was.

The cost of their love was becoming clearer.

Not just the fear and hiding, but the family they never had, the normal life that was denied to them.

Aunt Marie died in 1945.

Marcus continued, “Pneumonia.

” But really, I think she died of exhaustion.

Exhausted from years of looking over her shoulder, of living in fear, of carrying a secret that got heavier every day.

Uncle Thomas was devastated.

They’d been together for 22 years, and he said she was the only person who truly knew all of him, who loved all of him.

He lived another 23 years after she died, John observed.

He did, but part of him died with her.

He went through the motions, worked his job, came home, kept to himself.

My father checked on him regularly, made sure he was eating, made sure he wasn’t completely alone.

But Uncle Thomas was just waiting, I think, waiting to be with her again.

Marcus picked up the wedding photograph, holding it carefully.

This picture, this was the only photograph of them together that Uncle Thomas kept.

Everything else got destroyed or left behind when they fled New Orleans.

But this one he carried with him always.

After Aunt Marie died, he kept it by his bed.

He’d look at it every night before he went to sleep.

“What happened to it after he died?” John asked.

“I inherited his few belongings.

There wasn’t much.

He lived simply, saved nothing.

This photograph was in a box with a few other personal items.

I kept it for years, but when I moved into this facility, I had to downsize.

I sold most of my possessions at an estate sale.

I never thought he trailed off emotional.

I never thought anyone would care about their story.

I thought it would just be another old picture in a frame.

John felt the weight of responsibility.

This wasn’t just a historical curiosity.

This was two people’s entire life, their love, their sacrifice, their pain.

They deserved better, Marcus said quietly.

They deserved to live without fear, to have children, to grow old together without always hiding.

But the world wasn’t ready for them.

Maybe it still isn’t.

Their story matters, John said firmly.

What they endured, what they sacrificed for love that deserves to be remembered.

Marcus nodded, tears streaming down his weathered face.

Uncle Thomas told me once near the end of his life that he never regretted loving Aunt Marie.

Not for one second.

All the fear, all the hiding, all the things they gave up.

He said it was worth it because he got to love her and be loved by her.

He said that kind of love was rare and most people never find it.

So he considered himself blessed even with all the hardship.

John spent the following weeks organizing all the research materials he’d gathered, the photographs, the documents, the interview with Marcus, the historical context.

The story of Thomas and Marie Laurent was complete now, as complete as it could be.

Nearly a century after their wedding, he sat in his studio one evening, the original wedding photograph in front of him, and thought about what their story meant.

Two people who had dared to love across boundaries that society had deemed uncrossable.

two people who had paid an enormous price for that love.

Forced to flee their home, to live in fear for decades, to abandon art and family and any sense of security.

Marcus had given John permission to keep the photograph, saying he was too old to properly care for it and knowing it would be valued and preserved.

Tell their story, Marcus had said.

Make sure people understand what they went through.

But John found himself uncertain about what to do with the story.

Marcus had specifically asked that it not be made into a public spectacle.

No museum exhibitions, no dramatic presentations that would reduce their lives to a historical curiosity.

They lived in hiding.

Marcus had said, “Let their story be known, but let it be known with dignity and respect, not as entertainment.

” John understood this wasn’t a story with a happy ending.

There was no triumph here, no justice restored, no wrongs made right.

This was simply the truth of two people who had loved each other in a time and place that made such love a crime.

He created a detailed research file documenting everything he’d learned.

He wrote a careful account of their lives based on the evidence and Marcus’ testimony.

He preserved all the photographs and documents with archival quality materials.

But he did not publish articles, did not contact media, did not push for recognition.

Instead, he quietly shared the story with a few academic colleagues who specialized in African-American history and the history of anti-misogenation laws.

He wanted the story preserved in the historical record, available to researchers and scholars, but not sensationalized or exploited.

Marcus passed away 6 months after their meeting, dying peacefully in his sleep at age 82.

Jon attended the funeral, one of only a dozen mourners.

After the service, Marcus’s daughter approached John.

“My father told me about your research into Uncle Thomas and Aunt Marie,” she said.

“He was grateful that someone cared enough to find out what happened to them.

“He asked me to give you something if he died before he could.

” She handed John a small wooden box.

Inside was a tarnished silver trumpet mouthpiece.

This belonged to Uncle Thomas, she explained.

My father kept it all these years.

He wanted you to have it.

To remember that Uncle Thomas was more than just someone who passed for white.

More than just someone who broke the law by marrying the woman he loved.

He was an artist.

He was a man who made beautiful music.

John held the mouthpiece carefully, feeling its weight, imagining the music that had once flowed through it.

Thomas Laurent, trumpet player from TMA, forced to give up his art to protect his love.

Back in his studio, John placed the mouthpiece next to the wedding photograph.

two artifacts from a life lived in defiance of unjust laws.

Two reminders that love had always found a way to exist, even in the face of violence and oppression.

He thought about Marie, dead at 43, exhausted by years of fear.

He thought about Thomas, living 23 more years without her, keeping her photographed by his bed, remembering what they had shared.

Their story would never be widely known.

There would be no monuments, no public recognition of their courage.

But the truth had been recovered.

The photograph that had concealed their secret for a century had finally revealed it to someone who cared enough to understand.

John carefully returned the wedding photograph to its tarnished silver frame.

He would preserve it, care for it, ensure that it survived for future generations.

And with it, he would preserve their story, not as a tale of triumph, but as a testament to the price that love sometimes demanded.

Thomas and Marie Lauron had risked everything for each other.

They had lost so much, family, home, security, art, children, peace of mind.

But they had gained something, too.

A love that was real and true.

A partnership that endured through fear and hardship.

A commitment that lasted until death and beyond.

That John thought was worth remembering.

Not because their story ended happily, but precisely because it didn’t.

Because they showed that love could exist even in impossible circumstances.

Because they proved that some things, some precious, irreplaceable things were worth any sacrifice.

The photograph sat on his desk.

Thomas and Marie frozen in time on their wedding day.

June 16th, 1923.

Young, hopeful, terrified, and brave.

Two people who had dared to love when love was forbidden.

Their secret was no longer hidden.

Their story was no longer lost.

And that perhaps was the only justice they would ever receive.

News

When Historians Examined This 1860 Portrait Closely, They Discovered an Impossible Secret That Shouldn’t Exist in That Era ⚠️ — At first it was just another stiff Civil War–era likeness, starched collars, blank stares, nothing special, until a forensic scan caught a detail so out of time it made researchers step back from the screen, because suddenly the portrait felt less like history and more like a glitch, as if the past had accidentally exposed something it was never meant to reveal 👇

When historians examined this 1860 portrait closely, they discovered an impossible secret. Dr.Sarah Morrison had examined thousands of Civil War…

The Photo That History Tried to Erase: The Forbidden Wedding of 1920 Finally Resurfaces, and What It Shows Is Pure Scandal 💍 — Tucked away in a mislabeled archive box for nearly a century, this “lost” wedding portrait looks sweet at first glance—flowers, vows, forced smiles—but experts now say the couple should never have been allowed to marry, and the more the image is enhanced, the clearer it becomes that this wasn’t romance… it was rebellion captured in a single, dangerous frame 👇

The photo that history tried to erase. The forbidden wedding of 1920. The attic smelled of dust and forgotten memories….

It Was Just a Photo Between Friends — Until Historians Uncovered a Dark Secret Hidden in the Shadows and the Smiles Suddenly Felt Fake 📸 — At first it looked like harmless laughter frozen in sepia, arms slung over shoulders, the kind of memory you’d tuck into a family album, but once experts enhanced the image they spotted a chilling detail tucked between them, and those cheerful expressions started to feel staged, like two people pretending everything was fine while hiding something they prayed no one would ever see 👇

It was just a photo between friends. But historians have uncovered a dark secret. Dr.James Patterson had spent his academic…

This 1898 Photograph Hides a Detail Historians Completely Missed — Until Now, and What They Found Has Them Questioning Everything 📸 — For decades it gathered dust in a quiet archive, labeled “ordinary,” dismissed as just another stiff Victorian snapshot, until a high-resolution scan exposed one tiny, impossible detail lurking in the background, and suddenly the smiles looked fake, the poses suspicious, and experts realized they weren’t staring at a memory… they were staring at a secret frozen in time 👇

This 1888 photograph hides a detail historians completely missed until now. The basement archives of the Charleston County Historical Society…

This Portrait of Two Friends Seemed Harmless — Until Historians Spotted a Forbidden Symbol Hidden Between Them and Everything Fell Apart ⚠️ — At first it was just two smiling companions shoulder-to-shoulder in stiff old-fashioned suits, the kind of wholesome image you’d frame without a second thought, but a closer scan revealed a tiny, outlawed mark tucked into the shadows, and suddenly the photo wasn’t friendship… it was rebellion, secrecy, and a message never meant to survive the century 👇

This portrait of two friends seemed harmless until historians noticed a forbidden symbol. The afternoon sun filtered through the tall…

Experts Thought This 1910 Studio Photo Was Peaceful — Until They Zoomed In and Saw What the Girl Was Holding, and the Entire Room Went Cold 📸 — At first it looked like another gentle Edwardian portrait, lace dress, soft lighting, polite smile, but when archivists enhanced the image they noticed her tiny fingers clutching something oddly deliberate, something that didn’t belong in a child’s hands, and suddenly the sweetness curdled into dread as historians realized this wasn’t innocence… it was a clue 👇

Experts thought this 1910 studio photo was peaceful until they saw what the girl was holding. Dr.Maya Johnson’s hands trembled…

End of content

No more pages to load