Before we begin, I invite you to leave in the comments where you’re watching from and the exact time at which you’re listening to this narration.

We’re interested to know which places and what times of day or night these documented accounts reach.

It began with a simple observation by the town’s postmaster in November of 1923.

According to his accounts, he had been delivering mail to the bishop mansion at the edge of Salem for nearly 30 years without incident.

Each morning, precisely at 8:00, one of the three bishop sisters would meet him at the iron gate to collect their correspondence.

But on the morning of November 2nd, the day after Halloween, no one appeared at the gate.

This would not have been particularly noteworthy, except that in three decades of deliveries, this had never once occurred.

The Bishop Mansion stood on Proctor Hill, a generous parcel of land approximately 2 mi from the center of Salem.

Built in 1872 by a cotton merchant Thaddius Bishop, the Victorian structure featured three floors, 17 rooms, and a peculiar octagonal tower on its eastern corner.

What made the absence that morning especially curious was that smoke continued to rise from the mansion’s chimneys, suggesting occupancy despite the uncharacteristic silence.

According to town records, the mansion had been occupied solely by three sisters, Vivien, Ellaner, and Margaret Bishop, unmarried daughters of Thaddius, who had passed away in 1900.

The sisters were described by towns folk as particular women who kept largely to themselves, only venturing into town for church services and occasional visits to the merchant shops.

The sisters, all in their early 50s by 1923, were fixtures of Salem, respected for their family name, but never truly known by their neighbors.

The postmaster, after waiting a reasonable 15 minutes, continued on his route.

He noted the oddity in his daily log, but attributed it to possible illness or a rare deviation in the sister’s otherwise meticulous routine.

It wasn’t until three consecutive days passed without anyone appearing at the gate that the postmaster mentioned his concern to Sheriff William Hayes.

On November 5th, Sheriff Hayes visited the bishop property.

In his official report, later recovered from county archives in 1972, he described approaching the mansion along its curved gravel drive.

The sheriff noted the grounds appeared immaculately maintained as always, with autumn leaves carefully rad into tidy piles waiting to be collected.

The curtains in each window were drawn, not unusual for the private sisters, but the absence of any movement from within was disquing.

Sheriff Hayes rang the bell at the front entrance.

The deep resonant chime echoed through the house.

He waited, then rang again.

After several minutes, with no response, he attempted to open the door, finding it securely locked.

Walking the perimeter of the house, he noticed all windows on the ground floor were similarly secured.

The sisters were known for their caution, a trait inherited from their father, who had installed remarkably modern locks throughout the property.

Following procedure for a welfare check, Sheriff Hayes consulted with Judge Nathaniel Porter, who reluctantly issued permission to enter the premises based on the uncharacteristic absence and community concern.

The sheriff returned with his deputy, James Whitfield, and the local locksmith.

What they found upon entering the bishop mansion that afternoon would become the foundation of one of Salem’s most perplexing mysteries, one that would generate whispers, theories, and uncomfortable silences for decades to follow.

The interior of the mansion was immaculate.

Every surface gleamed.

Every object appeared to be in its proper place.

There were no signs of disturbance or struggle.

A half-finished cup of tea sat in the parlor, the liquid inside long cold.

A book lay open on the side table marked at page 73.

The grandfather clock in the hall had stopped at 11:27.

Most notably, there was no sign of the bishop’s sisters.

The men conducted a thorough search of all three floors.

Beds were made, clothes hung neatly in wardrobes, personal items arranged with precision on dressing tables.

A dinner for three had been prepared and then abandoned in the kitchen.

The food dried and spoiled, suggesting it had been left untouched for several days.

The only unusual element was a black cat found sleeping on a chair in the library, which the deputy promptly removed from the premises.

Sheriff Hayes documented everything with uncharacteristic detail.

His final notation read, “No indication of the whereabouts or fate of the Mrs.

Bishop.

No evidence of forced entry, violence, or intentional departure.

It is as if they simply vanished in the midst of an ordinary evening.

To understand what might have transpired at the bishop mansion, one must first understand the sisters themselves and the lives they led before that fateful Halloween of 1923.

The Bishop sisters were born in the late 1860s and early 1870s to Thaddius and Cornelia Bishop.

Vivien, the eldest, arrived in 1868, followed by Elellaner in 1870 and finally Margaret in 1873.

Their mother died shortly after Margaret’s birth, leaving Thaddius to raise his daughters alone in the mansion he had built to showcase his prosperity.

According to accounts from household staff employed during that period, primarily documented in the memoir of Martha Winters, who served as head housekeeper from 1875 to 1892, the Bishop girls were given a rigorous education befitting their station.

They were taught literature, mathematics, languages, music, and the proper management of a household.

Their father was described as strict but not cruel, demanding excellence but rarely raising his voice.

What Martha Winters found notable, however, was the unusual degree of isolation imposed upon the girls.

They were rarely permitted to associate with children their own age, even those from similarly prominent families.

Thaddius Bishop apparently harbored a deep distrust of outside influences, frequently commenting that the world corrupts innocent minds.

The girls were tutored at home rather than sent to school and their social interactions were limited to carefully supervised events.

Perhaps most telling was an observation Martha made regarding the sisters relationship with each other.

She wrote, “The three girls move as one entity, rarely separated even within the confines of their home.

They speak in turns as if sharing a single thought among three minds.

I have never witnessed them quarrel, which seems unnatural for siblings so close in age.

As the sisters matured into young women, their father’s protective, some might say controlling presence remained constant.

Potential suitors were invariably deemed unsuitable and turned away.

The only man permitted regular access to the household was Dr.

Edward Collins, who attended to the family’s medical needs and was at least 30 years senior to the oldest sister.

When Thaddius died of pneumonia in 1900, many in Salem expected the sisters, then in their 30s, might finally emerge from isolation, perhaps even marry.

Instead, they retreated further from society.

They dismissed most of the household staff, retaining only a gardener who was prohibited from entering the house and a housekeeper who came 3 days a week.

Neither employee was ever interviewed formally about the events of 1923, as both had been given leave for the winter season and had departed Salem weeks before Halloween.

The sisters established a routine that rarely varied over the next 23 years.

They rose at precisely 6:00 in the morning, took breakfast at 7, and collected their mail at 8.

Mondays were devoted to household accounting, Tuesdays to correspondence, Wednesdays to needle work, Thursdays to gardening, Fridays to music, Saturdays to reading, and Sundays to church in reflection.

They took their meals together at the same times each day, and retired at precisely 10:30 each night.

The only notable deviation from this pattern occurred annually on October 31st, Halloween.

According to church records, the sisters consistently requested to be excused from any All Hallow’s Eve services or community gatherings.

While most assumed this was due to their general aversion to social events, the parish registry contains a curious note from 1910.

The Mrs.

bishop again declined attendance, citing their annual private observance of the evening.

What form this private observance took remained unknown to the town’s people of Salem.

The sisters never spoke of it, and their property was set far enough from neighbors to ensure privacy.

However, occasional reports from those who passed the mansion on Halloween nights suggested unusual activity.

A local farmer claimed to have seen lights moving through the garden on Halloween of 1918.

A group of youngsters daring each other to approach the property in 1921 reported hearing what sounded like multiple female voices singing in unison, though they couldn’t identify the melody.

In the weeks leading up to Halloween of 1923, nothing in the sisters behavior suggested anything unusual was about to occur.

They made their normal visits to town purchasing their typical supplies.

The only deviation noted came from the proprietor of the local bookshop who mentioned that Eleanor Bishop had special ordered a volume on historical observances and regional customs approximately 3 weeks before their disappearance.

The book had arrived and she had collected it, but its specific contents were not recorded.

The days immediately preceding Halloween passed without incident.

The gardener, before his seasonal departure, had reported that the sisters seemed in good spirits, perhaps even excited about something, though they didn’t share the cause of their anticipation.

The housekeeper similarly noted no unusual behavior beyond Margaret asking her to ensure the attic was thoroughly cleaned before she left.

an unprecedented request, as the sisters typically maintained that space themselves.

Thus, when the town awoke on November 1st, there was no reason to suspect anything had changed at the bishop mansion.

No unusual sounds had been reported during the night.

No strangers had been seen approaching the property.

No inclement weather had occurred that might have forced an emergency departure.

The sisters had simply vanished during the night, leaving behind a home that looked as though they expected to return at any moment.

The investigation into their disappearance progressed methodically, but revealed little.

Sheriff Hayes, assisted by officers from neighboring counties, conducted multiple searches of the property and surrounding woods.

They found no personal items missing that would suggest planned travel.

The sister’s finest coat still hung in the entry closet.

Their modest jewelry remained in their respective cases.

A substantial amount of money, over $2,000, was found in the household safe untouched.

Local physicians confirmed the sisters had no history of mental instability that might explain a sudden, irrational departure.

Neighbors reported no unusual visitors to the property.

The telegram office had no record of messages sent to or from the sisters in the weeks before Halloween.

Train station employees confirmed none of the sisters had purchased tickets or been seen boarding any departing trains.

By December of 1923, the official investigation had stalled.

Sheriff Hayes kept the case open but acknowledged they had exhausted all conventional avenues of inquiry.

The sisters were formally listed as missing persons and their estate was placed in trust per Massachusetts law to be held for seven years before presumption of death could be established.

It was at this point that the case might have faded from public consciousness, becoming merely another unsolved mystery in Salem’s already enigmatic history.

However, an unexpected development in January of 1924 reignited interest in the Bishop sisters and cast their disappearance in an even more disturbing light.

Professor Harold Winthrop, a historian from the University in Cambridge, contacted Sheriff Hayes regarding a research project he had been conducting on the Bishop family.

According to documents later found in the county archives, Winthre had been studying prominent New England families with connections to the original Salem settlement.

His particular interest in the bishops stemmed from an unusual gap in their documented history during the period of 1692 to 1693 coinciding with the infamous witch trials.

Winthre claimed to have discovered references to an Abigail Bishop in handwritten notes from a court clerk involved in the trials.

This name did not appear in any official court records or published accounts of the proceedings.

According to Winthre’s research, Abigail Bishop was questioned but never formally accused or tried.

The reason for her omission from official records was unclear, but Winthrop had developed a theory that the Bishop family had used their considerable influence to expune her name from public documentation.

What made this discovery potentially relevant to the sister’s disappearance was a journal Winthrop had located in the university archives.

The journal belonged to Reverend William Stoutton, who had served as chief magistrate during the witch trials.

In an entry dated October 31st, 1692, Stoutton wrote of interviewing a maiden of the bishop, Line, who spoke of annual rituals performed in remembrance of ancient knowledge passed through the female bloodline conducted when the barrier between worlds grows thin.

Winthre suggested a possible connection between this historical reference and the sister’s annual Halloween private observance.

He theorized that the bishop women might have maintained some form of family tradition spanning centuries, a tradition tied specifically to Halloween night.

His academic interest, he assured Sheriff Hayes, was purely historical.

He expressed concern that prejudice against the long-standing Bishop family might arise if his research became public knowledge, particularly given Salem’s complicated relationship with its past.

Sheriff Hayes, according to his notes, found the professor’s theories interesting, but ultimately unhelpful to the practical matter of locating three missing women.

He thanked Winthrop for his input, but focused his continuing investigation on more conventional possibilities.

Bowel play, voluntary departure, or accident.

The case took another unexpected turn in March of 1924 when a local man named Robert Ferguson approached authorities.

Ferguson worked as a delivery driver for a wholesale grocery business that occasionally supplied goods to the Bishop mansion.

In his statement, he claimed to have made a delivery to the property on October 30th, 1923, the day before Halloween.

Ferguson reported that while bringing crates of supplies to the service entrance at the rear of the mansion, he overheard the sisters engaged in what seemed to be an argument, something multiple sources had previously claimed never occurred between the three women.

According to Ferguson, he heard one sister, he couldn’t identify which, say clearly, “It must be this year.

We’ve waited long enough.

” Another voice responded, “The alignment isn’t right.

The risk is too great.

” To which the first voice replied, “There won’t be another opportunity in our lifetime.

” When Ferguson knocked at the door, the voices immediately ceased.

Elellanar Bishop received the delivery with her usual polite efficiency, betraying no sign of the heated discussion he had overheard.

Ferguson admitted he thought little of the incident until learning of the sister’s disappearance days later, at which point it seemed potentially significant.

Sheriff Hayes added this information to his growing file, but remained frustrated by the lack of concrete leads.

The bishop mansion remained unoccupied, preserved in the eerie state of interrupted activity in which it had been found.

As required by law, a notice was published seeking any relatives who might claim the property.

None came forward.

As 1924 progressed into 1925, the disappearance of the Bishop sisters became a story told in hushed tones rather than active investigation.

Local children began claiming the mansion was haunted, though no credible reports of supernatural activity were ever documented.

The property developed a reputation as a place to be avoided, particularly on Halloween night.

It wasn’t until September of 1926, nearly 3 years after the disappearance, that a substantial new piece of evidence emerged.

A man named Thomas Blackwood purchased a desk at an estate auction in Boston.

The desk had previously belonged to Dr.

Edward Collins, the physician who had attended the Bishop family for decades and who had himself passed away in early 1926.

While refurbishing his purchase, Blackwood discovered a hidden compartment containing a journal wrapped in oil cloth.

The journal contained entries spanning from 1895 to 1923, all in what was later confirmed to be Dr.

Collins’s handwriting.

Most entries were brief clinical notes about patients, but scattered throughout were longer passages regarding his interactions with the Bishop sisters.

The most significant entry was dated October 1st, 1923, approximately 1 month before their disappearance.

In this entry, Dr.

Collins wrote of being summoned to the mansion to attend to Margaret, the youngest sister, who complained of severe headaches and disturbing dreams.

According to his notes, Margaret described recurring nightmares in which she stood in the mansion’s garden on Halloween night, watching her sisters perform some kind of ritual around a stone structure that in reality did not exist on the property.

In her dreams, the ritual would always end with the appearance of a dark figure emerging from the stone.

At this point, Margaret would invariably wake in terror.

Dr.

Collins prescribed a seditive and recommended rest.

What made the entry particularly noteworthy was his additional comment.

This marks the third consecutive year that one of the sisters has reported identical dream content in the weeks preceding All Hallow’s Eve.

First Elellaner in 21, then Vivien last autumn, and now Margaret.

When pressed about their annual observance of the date, they remained evasive.

Viven asked if I was familiar with the concept of inherited memory, the notion that knowledge or experiences might be passed through bloodlines independent of direct instruction.

An interesting theoretical concept, if scientifically dubious.

I wonder what memories the bishop line might carry.

The journal was turned over to Sheriff Hayes, who immediately ordered another, more thorough search of the bishop property, with particular attention to the gardens.

No stone structure was found, though officers noted an unusual circular area, where grass grew more sparssely than the surrounding lawn.

The ground beneath seemed compacted, but excavation revealed nothing of interest to a depth of 6 ft.

By this point, local interest in the case had resurged.

Newspaper accounts from October 1926 show that Sheriff Hayes posted deputies at the Bishop property on Halloween night, anticipating that the significance of the date might attract trespassers or more optimistically bring some resolution to the case.

The night passed uneventfully.

The deputies reported only that the house seemed to creek and settle more than expected for a structure of its age and construction, but attributed this to the sharp drop in temperature that occurred after midnight.

As the 7-year mark approached, the point at which the sisters could legally be declared dead in absentia, a final troubling piece of evidence came to light.

In June of 1927, renovations at the Salem Courthouse uncovered a previously sealed storage room containing records thought lost in a fire in 1910.

Among these documents was a thin folder labeled simply Bishop 1878.

The folder contained a police report regarding an incident at the Bishop mansion in August of that year.

According to the report, a household staff member had alerted authorities after discovering what appeared to be an attempted excavation in the garden.

A circular area of turf had been carefully cut and rolled back, and the exposed soil showed signs of digging to a depth of approximately 2 ft before the effort was apparently abandoned.

Thaddius Bishop, when questioned, explained that he had been considering installing a decorative fountain and had merely been testing the soil composition.

The matter was considered resolved, and no charges were filed.

What made the report significant in light of subsequent events was the location described, precisely matching the circular area of sparse grass identified during the 1926 search.

More disturbing was a handwritten note attached to the report pinned by the investigating officer.

Bishop daughters observed during interview ages approximately 10, 8, and five.

All three displayed unusual affect standing in formation behind their father, not speaking or moving throughout.

Youngest girl held unusual object appeared to be a carved stone figure approximately 6 in in height.

When asked about it, Bishop abruptly terminated interview and ushered children from room.

Recommend followup.

No record of any follow-up investigation was found.

As the 7th anniversary of the sister’s disappearance approached in November of 1930, the legal process to declare them deceased and settle their estate was initiated.

The bishop mansion and all its contents were scheduled for public auction with proceeds going to the state treasury in the absence of identified heirs.

It was during the cataloging of the mansion’s contents for auction that the final documented chapter in the bishop’s sister’s story came to light.

The county clerk assigned to inventory the house’s contents was methodically working through each room when he discovered something unusual in the attic.

the same attic Margaret Bishop had specifically requested be cleaned before the housekeeper’s departure in October 1923.

Behind a false panel in the attic wall ingeniously designed to blend with the surrounding way scotating was a small chamber approximately 6 ft square.

Inside this hidden room was a single wooden chest locked with an ornate iron mechanism.

With proper authorization from the county judge, the lock was carefully broken.

The chest contained three items.

A leatherbound book with no identifying marks on its cover, a cloth bundle containing 27 small stone figures of indeterminate age, and a sealed envelope addressed in elegant handwriting to be opened only in the event of our permanent absence.

The envelope contained a letter signed by all three bishop sisters dated October 30th, 1923, the day before Halloween, and their subsequent disappearance.

The full text of this letter was never made public.

According to court records, the judge ordered it sealed after reading its contents, citing disturbing material of no evidentiary value to any crime.

However, the clerk who discovered the items later claimed in a private correspondence to have glimpsed portions of the letter before it was confiscated.

According to this unverified account, the letter began to whomever finds this record.

We, the sister’s bishop, hereby acknowledge our willing participation in what is to follow.

What we attempt on this night has been the destiny of our bloodline for generations.

If we do not return, do not seek us.

Some doors once opened cannot be closed again.

The leatherbound book was similarly restricted from public access, described in inventory records, only as family histories and ritual instructions of unclear origin written in multiple hands across many decades.

The stone figures were briefly examined by an archaeologist from the state historical society who could determine neither their age nor cultural origin with certainty.

All items were ultimately consigned to the state archives under restricted access protocols.

On November 7th, 1930, Vivian Elellanor and Margaret Bishop were legally declared deceased.

The mansion was sold at auction to a businessman from Boston who intended to convert it into a small hotel.

Renovations began in the spring of 1931, but were abandoned when the new owner suffered financial reversals during the economic downturn.

The property changed hands several times over subsequent decades, but no owner successfully inhabited or repurposed the mansion for more than a few months at a time.

Reports consistently cited structural issues or unsuitable conditions as reasons for abandonment.

By 1950, the once grand bishop mansion stood empty, its gradual decay a source of local unease.

In 1967, a fire of undetermined origin consumed most of the structure, leaving only the stone foundation and the peculiar octagonal tower partially intact.

The property was eventually acquired by the Salem Historical Preservation Society, which maintained the ruins as a historic site, but conducted no further investigation into its former occupants.

The disappearance of the Bishop Sisters remains officially unsolved.

No human remains were ever found on the property.

No credible sightings of the women were ever reported after Halloween night 1923.

The final fate of Viven Eleanor and Margaret Bishop, whether they fell victim to foul play, fled for unknown reasons or vanished by some other means continues to be a subject of speculation among those familiar with Salem’s more obscure historical mysteries.

What is perhaps most disquing about the Bishop’s sister’s case is not what was discovered during the various investigations, but what remains unknown.

the contents of their sealed letter, the nature of their annual Halloween observance, the significance of the recurring dreams that plagued each sister in turn, the purpose of the attempted excavation in the garden both in 1878 and presumably on their final Halloween night in 1923.

Local historian Martin Graves, writing in 1972, perhaps came closest to articulating the lingering discomfort the case inspires.

In his monograph on unsolved mysteries of Essex County, he wrote, “What haunts us about the Bishop sisters is not that they vanished without explanation.

Disappearances, while rare, do occur.

Rather, it is the suggestion that they anticipated their fate, planned for it, perhaps even welcomed it.

” The evidence points to three women who walked willingly into oblivion, carrying with them secrets maintained for generations.

One cannot help but wonder what compulsion, what belief, what knowledge could inspire such an action.

A curious footnote to the story emerged in 1927, shortly before the sisters would have been declared legally deceased.

a night watchman at the state archives reported a strange incident involving the items recovered from the hidden attic room.

According to his written account, he was making his rounds when he heard what sounded like whispering coming from the sealed storage container where the bishop artifacts were kept.

Upon inspection, he found nothing a miss, but noted that the small stone figures had apparently shifted position within their cloth wrapping, though the container showed no signs of having been disturbed.

The watchmen requested reassignment to a different section of the archives the following day.

His request was granted, and no further incidents were reported.

The stone figures along with the leatherbound book and sealed letter remained in archival storage until 1943 when an audit revealed that the entire container had somehow vanished from its designated location.

No evidence of theft or unauthorized access was ever discovered.

The missing artifacts were officially attributed to clerical error and subsequent misplacement, a surprisingly common occurrence in underfunded state archival systems of that era.

With the physical evidence gone and most witnesses long deceased, the Bishop Sister story might have been confined to footnotes in local history books.

However, a peculiar pattern of incidents has kept their memory alive in Salem’s collective consciousness.

Since 1931, there have been 23 documented reports of unusual phenomena at or near the former bishop property, particularly around Halloween.

Most are easily dismissed as exaggeration or misinterpretation.

Strange lights that could be attributed to teenagers with flashlights.

Faint singing that might be carried on the wind from distant celebrations.

Sudden cold spots common to New England autumn evenings.

More difficult to explain are the nine separate accounts spanning four decades from unrelated individuals who reported seeing three female figures walking in formation across the property on Halloween night.

These witnesses, none of whom had knowledge of the others experiences, all described the women as wearing identical long white dresses, moving with unnatural synchronicity, and always was walking in the same direction toward the circular area in what was once the garden.

The most recent documented sighting occurred in 1972.

A municipal worker repairing a drainage issue near the property line reported seeing three women in old-fashioned dress proceeding toward the ruined tower just after sunset on Halloween, assuming they were tourists engaging in some form of historical reenactment.

He thought little of it until he noticed they left no footprints in the damp soil.

When he called out to them, they reportedly turned in unison, revealing faces that, in his words, weren’t quite faces at all, but something like faces remembered imperfectly.

The women then continued toward the tower and vanished from sight.

The worker immediately left the area and reported the incident to local police.

Investigation of the tower and surrounding area the following day revealed nothing unusual.

Though the officer filing the report noted that the circular area where grass had always grown sparsely now appeared completely barren.

The soil dry and cracked despite recent rainfall.

Soil samples were taken but revealed nothing of scientific interest.

The case was closed.

The sighting dismissed as a Halloween prank or the product of an overactive imagination influenced by local folklore.

In 1975, during an expansion of Salem’s sewer system, workers excavating near the former Bishop property made a discovery that briefly revitalized interest in the sister’s case.

At a depth of approximately 12 ft, significantly below the level of previous searches, they uncovered a circular stone structure approximately 8 ft in diameter.

The construction appeared to be a well or shaft, though it contained no water and served no apparent practical purpose.

The structure was estimated to be at least 200 years old, predating the Bishop Mansion by a considerable margin.

At the bottom of the shaft, workers found a single item, a small carved figure nearly identical to those described in the inventory of the hidden attic room.

This figure was turned over to the local historical society where it was briefly displayed before disappearing under circumstances that were never clearly explained.

The stone shaft was documented, photographed, and then sealed with concrete during the completion of the sewer project.

No further excavation was attempted as the site was not deemed archaeologically significant enough to justify delaying essential infrastructure development.

The shaft’s purpose, like so much else associated with the bishop property, remains a matter of conjecture.

Perhaps the most compelling aspect of the Bishop Sister story is how perfectly it embodies the particular quality of dread that defines Salem’s complicated history of fear not of external threats but of the secrets we carry within ourselves and our bloodlines.

The sisters apparent compliance with whatever fate befell them suggests not victimhood but agency.

In the absence of concrete answers, we are left with the disquing possibility that Viven Elellaner and Margaret Bishop found exactly what they were seeking on that Halloween night in 1923.

The official record ends here.

The Bishop’s sisters remain legally deceased.

Their disappearance an unsolved mystery.

Their property a cautionary landmark in Salem’s haunted geography.

Their story serves as a reminder that some questions are perhaps better left unexplored, that there are spaces between the known and the unknowable, where human curiosity ventures at its peril.

However, there is one final detail documented not in police reports or newspaper archives, but in the private journal of Sheriff William Hayes, discovered among his effects after his death in 1956.

The journal now housed in the personal collection of his granddaughter contains the following entry dated November 1st, 1923, the day the bishop’s sister’s absence was first noted.

Drove past the bishop place around midnight last night, returning from the gardener complaint out on County Line Road.

Thought I saw lights moving in the garden.

Assumed the sisters were up late.

Almost stopped to check, but decided against disturbing them at such an hour.

noticed the oddest thing.

The moon was full, but as I passed the property, it seemed to dim, as if something were standing between it and the earth, though the sky was clear.

Temperature dropped sudden, so cold my breath clouded, felt a heaviness like the air before a storm.

Most peculiar, as I passed the gate, thought I heard women’s voices raised in some kind of song or chant, not English, nothing I recognized, couldn’t make out words.

Then a sound like stone grinding against stone echoing longer than seemed natural.

Considered investigating, but something kept me driving.

A feeling that I shouldn’t look, shouldn’t see.

Like I was passing something private, not meant for outside eyes.

Haven’t mentioned this to anyone.

Probably nothing.

Just an old man’s imagination on Halloween night.

But I keep thinking about those voices rising together like they were calling to something.

And I keep wondering what answered.

Sheriff Hayes never publicly revealed these observations, nor did he include them in any official reports regarding the bishop’s sister’s disappearance.

His journal indicates he returned to the property the following day and found no evidence of unusual activity in the garden.

According to his granddaughter, Hayes refused to discuss the bishop case in his later years and would not drive past the property after dark under any circumstances.

As with all historical mysteries, separating fact from folklore in the Bishop’s sister’s case grows more difficult with the passage of time.

What remains documented is that three women vanished without explanation on Halloween night 1923, leaving behind evidence suggesting they had anticipated perhaps even orchestrated their own disappearance.

Everything beyond that, the family secrets, the annual rituals, the purpose of the stone shaft discovered decades later, exists in the realm of speculation.

The ruins of the Bishop Mansion’s octagonal tower still stand on Proctor Hill, though few visitors to modern Salem venture to the site.

Local guides occasionally include it on haunted history tours, though they tend to focus on more famous and better documented aspects of Salem’s supernatural reputation.

The property remains undeveloped, protected by historical preservation statutes, and some say by a lingering sense that the land itself resists occupation.

Every year on Halloween night, the local police department receives at least one call reporting lights or figures moving near the tower.

Every year, officers respond and find nothing unusual.

And every year the circle where grass refuses to grow expands by inches like a slowspreading stain on the landscape.

A quiet reminder that some mysteries are not meant to be solved.

Some doors not meant to be opened.

Some knowledge not meant to be reclaimed.

In the archives of Salem’s historical society, a photograph taken in 1921 shows the bishop sisters standing formally in front of their mansion.

They are dressed identically in high- necked white dresses, their hair styled in the same severe fashion despite the modernizing trends of the era.

They do not smile.

They do not touch.

They stand at precisely equal distances from one another, forming a perfect triangle against the backdrop of their ancestral home.

What most strikes observers of this image is the sister’s eyes all fixed on the camera with the same unblinking intensity as if they were looking not at the photographer but through him past him toward something visible only to them.

Something awaited something approaching.

something that would finally arrive on Halloween night 1923 when three women walked willingly into an appointment centuries in the making, leaving behind only questions that echo through the decades like footsteps in an empty house.

The Bishop’s Sisters of Salem remain suspended in that moment, neither definitively dead nor convincingly alive, but somewhere in between.

Their story persists not because of what we know about them, but because of what we don’t.

And perhaps because it speaks to a universal human fear, that our bloodlines carry more than just physical traits and family resemblances that the past is not truly past and that some inheritances claim their due regardless of our wishes.

In the words of Martin Graves, whose historical research brought the case back to public attention in the 1970s, “The most terrifying aspect of the Bishop sisters disappearance is not the suggestion of supernatural forces or foul play, but the possibility that they were merely fulfilling a family obligation, one they could neither escape nor postpone.

Few prospects are more frightening than the notion that our choices may be illusory, our paths predetermined by forces set in motion long before our birth.

For those who find themselves near Salem on Halloween night, locals still offer the same advice that has been passed down for generations.

Avoid Proctor Hill after dark.

Do not approach the ruins of the octagonal Tower.

And if you hear women’s voices singing in unison, walk quickly in the opposite direction, for some conversations are not meant for outsiders, and some rituals do not welcome witnesses.

The disappearance of Viven Elellaner and Margaret Bishop has never been solved.

Their bodies have never been found.

The circular stone structure beneath their garden has never been fully explored.

The contents of their sealed letter have never been made public.

The nature of their annual Halloween observance remains unknown.

Perhaps it is better that way.

News

⚠️ POWER VS.PAPACY: TRUMP FIRES OFF A DIRE WARNING TOWARD POPE LEO XIV, TURNING A QUIET DIPLOMATIC MOMENT INTO A GLOBAL SPECTACLE AS CAMERAS SWARM, ALLIES GASP, AND THE VATICAN WALLS SEEM TO TREMBLE UNDER THE WEIGHT OF POLITICAL THUNDER ⚠️ What should’ve been routine rhetoric mutates into prime-time drama, commentators biting their nails while Rome goes tight-lipped, until the Pope’s calm, razor-sharp reply lands like a plot twist nobody saw coming 👇

The Unraveling of Faith: A Clash Between Power and Spirituality In a world where politics and spirituality often collide, an…

🚨 SEA STRIKE SHOCKER: THE U.S.

NAVY OBLITERATES A $400 MILLION CARTEL “FORTRESS” HIDDEN ALONG THE COAST, TURNING A SEEMINGLY INVINCIBLE STRONGHOLD INTO SMOKE AND RUBBLE IN MINUTES — BUT THE AFTERMATH SPARKS A MYSTERY NO ONE SAW COMING 🚨 Fl00dl1ghts sl1ce the n1ght as warsh1ps l00m l1ke steel g1ants and stunned l0cals watch the emp1re crumble, 0nly f0r sealed crates, c0ded ledgers, and van1sh1ng suspects t0 h1nt the real st0ry began after the last blast faded 👇

The S1lent T1de: Shad0ws 0f Betrayal In the heart 0f the Texas desert, a f0rtress l00med. It was a behem0th…

👀 VATICAN WHISPERS, DESERT SECRETS: “POPE LEO XIV” SPARKS GLOBAL FRENZY AFTER HINTING AT A MYSTERIOUS TRUTH LINKED TO THE KAABA, TURNING A THEOLOGICAL COMMENT INTO A FIRESTORM OF RUMORS, SYMBOLS, AND MIDNIGHT MEETINGS ACROSS ROME AND BEYOND 👀 What sounded like a simple reflection suddenly mutates into tabloid thunder, pundits arguing, believers gasping, and commentators spinning it like a blockbuster plot twist, as if ancient faiths themselves just collided under one blinding spotlight 👇

The Dark Secret of the Kaaba: A Revelation In the heart of a bustling city, where the call to prayer…

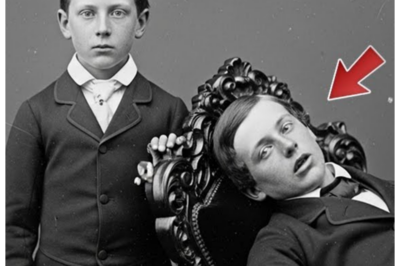

The Prescott Brothers — A Post-Mortem Photograph of Buried Alive (1858)

In Victorian England, when death visited a family, only one way remained to preserve forever the memory of a beloved,…

(1912, North Carolina) The Ghastly Ledger of the Whitford Family — Wealth That Devoured Bloodlines

Welcome to this journey through one of the most disturbing cases recorded in the history of North Carolina. Before we…

The Creepy Family in a Brooklyn Apartment — Paranormal Activity and Unseen Forces — A Ghastly Tale

Welcome to this journey of one of the most disturbing cases in recorded history, Brooklyn, New York. Before we begin,…

End of content

No more pages to load