In 1901, a Family Takes a Photo.

The Corner of the Room Holds a Dark Secret

In 1901, a family takes a photo.

The corner of the room holds a dark secret.

Dr.Margaret Chen had seen thousands of photographs in her 20 years as a historical archivist at the Chicago Historical Society.

But something about this particular image made her pause midcating.

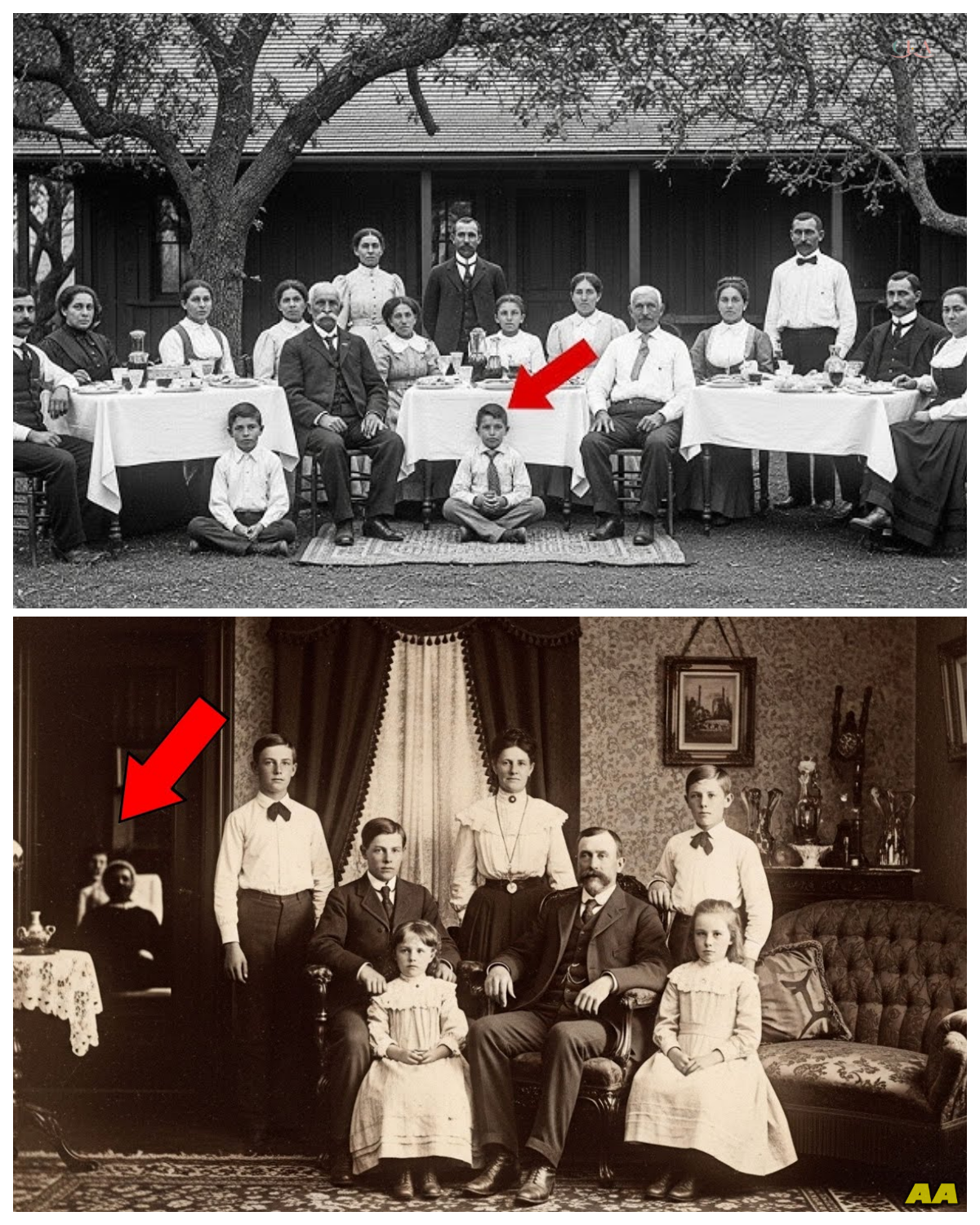

The photograph, recently donated by the estate of Elellanar Whitmore, showed a typical middle-class American family from 1901.

a stern-faced father in his Sunday best, a mother in a high collared dress with intricate lace work, and three children arranged formally in their modest parlor.

The sepia toned image captured the Witmore family during the height of the progressive era, when photography was still a formal affair, requiring several minutes of absolute stillness.

Young Thomas, perhaps 8 years old, stood rigidly beside his father’s chair, while his sisters, Mary and Catherine, sat primly on a velvet seti.

Everything appeared perfectly normal for a turn of the century family portrait, the heavy drapes, the ornate wallpaper, the carefully arranged furniture.

But Margaret’s trained eye caught something that made her breath catch in her throat.

In the far corner of the room, partially obscured by shadows and easily dismissed as part of the room’s decor, was something that shouldn’t have been there.

She leaned closer to her desk lamp, adjusting her glasses and squinting at the grainy detail.

“That’s impossible,” she whispered to herself, reaching for her magnifying glass.

The afternoon Chicago sun streamed through her office window as Margaret examined the photograph more carefully.

What she had initially mistaken for a decorative vase or ornamental stand in the corner was something far more disturbing.

The shape was wrong, the proportions unsettling.

As she studied the shadows and highlights, a chill ran down her spine.

This wasn’t just another family photograph.

This was evidence of something much darker, something that had been hidden in plain sight for over a century.

Margaret’s hands trembled slightly as she set down the magnifying glass, knowing that her discovery would change everything about how this family’s story would be remembered.

Margaret spent the rest of that afternoon researching the Witmore family in the society’s extensive records.

What she found painted a picture of a respected Chicago family who had prospered during the city’s rapid growth following the great fire of 1871.

James Whitmore had been a successful grain merchant, capitalizing on Chicago’s position as the railroad hub of America.

His wife, Helen, was known for her charitable work with immigrant families, settling in the city’s expanding neighborhoods.

The family had lived in a substantial brick house on the near north side in what was then considered one of Chicago’s most desirable residential areas.

James Whitmore was described in contemporary newspaper accounts as a pillar of the community, a member of the Chamber of Commerce, a regular attendee at Trinity Episcopal Church, and a generous contributor to various civic causes.

But as Margaret dug deeper into the historical record, she began to notice gaps in the family’s story.

The photograph was dated 1901.

Yet, she could find no record of the Whites after 1902.

It was as if the entire family had simply vanished from Chicago society.

Property records showed that their house had been sold in early 1903 to settle debts, but there was no indication of where the family had gone.

More puzzling still were the conflicting accounts of the family’s reputation.

While most sources praised James Whitmore’s business acumen and community involvement, Margaret discovered several cryptic references in private letters and diary entries from the period.

One entry from the diary of a contemporary society matron mentioned troubling rumors about the Witmore household and expressed relief that certain unsaavory associations had finally been severed.

As the evening shadows lengthened across her office, Margaret found herself staring once again at the photograph.

The family appeared so normal, so typical of their era.

Yet that mysterious object in the corner seemed to mock their respectable facade.

She made a decision that would consume the next several weeks of her life.

She would uncover the truth about what had really happened to the Witmore family and what dark secret they had been hiding in their elegant parlor.

The next morning, Margaret arrived at the historical society with a renewed sense of purpose.

She had barely slept, her mind racing with possibilities about what she might have discovered in that corner of the Witmore parlor.

She immediately contacted Dr.

James Morrison, a colleague at Northwestern University, who specialized in photographic analysis and forensic examination of historical images.

Margaret, you sound excited about something, Dr.

Morrison noted when she called him before 8 a.

m.

ut that doesn’t belong, and I need to know if I’m seeing what I think I’m seeing.

Margaret’s voice carried an urgency that made her colleague take notice.

An hour later, Dr.

Morrison arrived with his specialized equipment, high-powered magnifiers, digital scanners, and computer software designed to enhance and analyze historical photographs.

As he carefully examined the Witmore family portrait, his expression grew increasingly grave.

Margaret, this is this is disturbing,” he said quietly, adjusting the focus on his magnifier.

“What you’re seeing in that corner, it’s not a piece of furniture or decoration.

the proportions, the way the light falls on it.

I’m afraid you may have stumbled onto evidence of something criminal.

Together, they work to digitally enhance the image, slowly bringing the shadowed corner into clearer focus.

What emerged made both historians fall silent.

The shape in the corner was unmistakably human, small, contorted, and clearly not posed for the photograph like the rest of the family.

“We need to contact the police,” Dr.

Morrison said finally.

This might be over a century old, but if this photograph shows what I think it shows, we’re looking at evidence of a crime that was never investigated.

” Margaret nodded.

Though part of her wanted to continue her research privately, as a historian, she was driven by the need to uncover the truth, but she also understood the weight of what they had discovered.

This wasn’t just academic research anymore.

This was potentially evidence of murder, hidden for over 120 years in what appeared to be an innocent family photograph.

Detective Sarah Rodriguez of the Chicago Police Department’s cold case unit had investigated many unusual situations during her 15-year career, but she had never been called to examine a photograph from 1901.

When Margaret and Dr.

Morrison contacted the department, their discovery was initially met with skepticism.

However, the enhanced images they provided were compelling enough to warrant official investigation.

I have to admit this is a first for me.

Detective Rodriguez told Margaret as they sat in the historical society’s conference room.

We don’t usually open criminal investigations based on century old photographs.

But what you found here is significant.

Detective Rodriguez had brought her own forensic photography expert, Officer Michael Park, who had experience with digital enhancement and crime scene analysis.

As they examined the enhanced images on Dr.

Morrison’s laptop.

The room fell silent except for the hum of the building’s heating system.

The positioning suggests this person was not willingly participating in the photograph.

Officer Park observed clinically.

The body language, the way the limbs are arranged.

This looks like someone who was either deceased or unconscious when this picture was taken.

Margaret felt a chill run through her as the reality of their discovery sank in.

But how could a family take a portrait with with that in the background? How could the photographer not have noticed? That’s what we need to find out, Detective Rodriguez replied.

I’m going to need everything you can find about this family.

Property records, business dealings, social connections, any legal troubles.

If a crime was committed, there might be other evidence that was overlooked at the time.

The detective paused, studying the faces of the Witmore family members in the photograph.

Look at their expressions, she said quietly.

The father appears nervous, almost guilty.

The mother’s smile doesn’t reach her eyes.

Even the children seem uncomfortable.

This wasn’t just a family portrait.

This was a family with secrets.

As they planned their investigation, Margaret realized that her academic curiosity had evolved into something much more serious.

They were no longer just researching history.

They were potentially seeking justice for a victim whose death had been concealed for over a century.

The weight of that responsibility settled heavily on her shoulders.

As they prepared to dig deeper into the dark secrets of the Whitmore family, the investigation expanded rapidly as Detective Rodriguez’s team began examining every available record related to the Whitmore family.

Margaret found herself working closely with the police, her historical expertise proving invaluable in navigating the archival records of early 20th century Chicago.

What they discovered painted an increasingly troubling picture of the supposedly respectable family.

James Whitmore’s business dealings upon closer examination revealed several questionable associations.

While his grain merchant business was legitimate, Detective Rodriguez’s financial analysis showed large unexplained cash deposits in his bank accounts throughout 1900 and 1901.

These deposits coincided with a period when Chicago was experiencing significant problems with organized crime and labor violence.

More disturbing still were the personnel records they uncovered.

The Witmore household had employed an unusually high turnover of domestic staff, housekeepers, cooks, and nursemaids who had worked for the family for only brief periods before leaving without providing forwarding addresses.

Margaret found several help wanted advertisements placed by Helen Whitmore in Chicago newspapers.

Always seeking discreet, reliable domestic help for private household.

This pattern suggests they were having difficulty keeping staff.

Detective Rodriguez observed as they reviewed the employment records.

People were leaving and they were leaving quickly.

In that era, domestic positions were typically long-term employment.

This level of turnover indicates something was wrong in that household.

The breakthrough came when Margaret discovered a diary entry from Martha O’Brien, an Irish immigrant who had briefly worked as a cook for the Whitmore in early 1901.

O’Brien’s diary, housed in the Chicago Immigration Museum, contained several entries about her brief employment with the family.

The master keeps strange hours, O’Brien had written in her careful script.

Visitors come at all times of night, and I am instructed never to answer the door after dark.

Mrs.

Whitmore warned me never to enter the front parlor without permission, and never to ask questions about the sounds I might hear from that room.

Most chilling was O’Brien’s final entry about the Whites.

I could not remain in that house another day.

The things I witnessed, the poor soul I glimpsed in the corner of that room.

I feared for my own safety.

I pray God forgives them for what they have done, for I cannot.

Armed with Martha O’Brien’s diary entries, the investigation team began searching missing person reports from 1901 Chicago.

What they found confirmed their worst suspicions and added a heartbreaking human element to their century old case.

Among the records at the Chicago Police Archives, they discovered a report filed by Patrick Sullivan, a young Irish immigrant who had been desperately searching for his missing sister, Bridget.

Bridget Sullivan, according to the missing person report, was 18 years old when she disappeared in March 1901.

She had been working as a domestic servant for various wealthy families in Chicago while sending money back to her family in County Cork, Ireland.

Patrick’s statement to police described his sister as a good girl, reliable, and hardworking, who would never leave without word to her family.

The connection became clear when Margaret cross referenced employment records with the missing person report.

Bridget Sullivan had been hired by the Whitmore family as a housemmaid in February 1901, just weeks before she vanished.

According to Patrick’s statement, Bridget had written to her family expressing concern about her new employment, mentioning strange goings on in the household and her intention to seek other work.

She wrote that she was frightened.

Detective Rodriguez read from Patrick Sullivan’s original statement.

She said the master of the house had unnatural interests and that she had seen things that no Christian soul should witness.

That was the last anyone heard from her.

Dr.

Morrison enhanced the photograph further, focusing on what they now believed to be Bridget Sullivan’s remains in the corner of the Whitmore parlor.

The digital enhancement revealed details that made the team’s blood run cold.

A young woman’s dress from the period, a hand positioned at an unnatural angle, and what appeared to be bindings around the wrists.

Margaret felt physically sick as she studied the enhanced images.

They killed her and then they took a family portrait with her body in the room.

How could anyone be so callous, so evil? People have been capable of terrible things throughout history, Detective Rodriguez replied grimly.

“What’s different here is that they documented their crime.

This photograph was their mistake.

Evidence they never realized they were creating.

” As the investigation deepened, a horrifying pattern emerged that extended far beyond the murder of Bridget Sullivan.

Detective Rodriguez’s team discovered that James Whitmore had been involved with a secretive organization that operated in Chicago’s elite social circles during the early 1900s.

This group, which had no official name, but was referenced in several private correspondences as the society, engaged in activities that shocked even the experienced investigators.

Through painstaking research in private archives and sealed court records, they uncovered evidence that the society was involved in human trafficking, particularly targeting vulnerable immigrant women who worked as domestic servants.

These young women, many of them Irish, Italian, and Polish immigrants with no family connections in America, would simply disappear.

When their absence was reported, they were dismissed by authorities as unreliable immigrants who had likely moved on to other cities.

Whitmore wasn’t just a member, Detective Rodriguez explained to Margaret as they reviewed their findings.

Based on these financial records and correspondence, he was one of the leaders.

His grain business was a front.

He was making his real money from trafficking women to wealthy men throughout the Midwest.

The photograph they realized had been taken as some sort of trophy or proof of the group’s activities.

The casual way the Witmore family posed with Bridget Sullivan’s body in the background suggested that this wasn’t their first victim, but rather part of an established pattern of violence that had become normalized within their household.

Margaret discovered additional evidence in the records of St.

Patrick’s Church, where Father Thomas McKenna had kept detailed notes about missing parishioners.

His private journals preserved in the Chicago Arch Dascese archives contained heartbreaking entries about families seeking help to find their missing daughters, sisters, and wives.

The evil that prays upon our most vulnerable souls continues to grow.

Father McKenna had written in 1901.

I fear that among our city’s most respected citizens lurk predators who view these innocent girls as nothing more than commodities to be traded and discarded.

The priest’s notes included the names of at least 12 young women who had disappeared while working for wealthy families in Chicago’s north side between 1899 and 1902.

All had been recent immigrants.

All had worked as domestic servants, and all had vanished without trace, their cases dismissed by police as runaways or women who had likely moved to other cities seeking better opportunities.

The investigation revealed why the Whitmore family had disappeared so suddenly from Chicago society.

In 1902, Detective Rodriguez’s team discovered that Father McKenna had not remained silent about his suspicions regarding the missing women.

In late 1901, the priest had begun making inquiries with police and city officials, demanding investigations into the disappearances of his parishioners.

Through archived correspondence between Father McKenna and police superintendent Francis O’Neal, they learned that the priest had specifically named several wealthy families, including the Whites, as potential suspects in the disappearances.

While Superintendent O’Neal had initially dismissed these concerns, the priest’s persistence had begun to draw unwanted attention to James Whitmore and his associates.

McKenna was getting too close, Margaret observed as she read through the priest’s increasingly urgent letters to city officials.

He was connecting the dots between the missing women and the families they had worked for.

The photograph they realized had been taken in March 1901, just days after Bridget Sullivan’s disappearance and weeks before Father McKenna began his formal inquiries.

It was likely meant as a private record for the society documenting their crime for the twisted satisfaction of its members.

Bank records showed that James Whitmore had begun liquidating his assets in December 1901, converting property and investments into cash and gold.

By February 1902, the family had left Chicago entirely, leaving behind only debts and their former associates to face any potential investigation.

Through passenger manifests and immigration records, Detective Rodriguez’s team traced the family’s escape route.

The Whitmore had traveled by train to New York City where they boarded a steam ship bound for Argentina.

In the early 1900s, Argentina was a popular destination for wealthy Americans seeking to escape legal troubles as the country had limited extradition agreements with the United States.

They started new lives in Buenosire, Detective Rodriguez explained.

James Whitmore became Santiago Blanco, a wealthy cattle rancher.

Helen became Elena, and the children took on new Spanish names.

They lived comfortable lives in South America while their victims families in Chicago never learned what had happened to their daughters.

The realization that the Whites had escaped justice and lived prosperous lives while their victims remained forgotten added another layer of tragedy to the case.

While the Witmore family had long since escaped earthly justice, Detective Rodriguez was determined that their crimes should not remain hidden.

Working with Margaret and the Chicago Historical Society, she began the process of formally documenting their findings and ensuring that the victims would finally be remembered and honored.

The first step was contacting the descendants of the missing women.

Through genealogical research and immigration records, they were able to trace the families of several victims, including Bridget Sullivan.

Her great great nephew, Michael Sullivan, still lived in Chicago and worked as a carpenter, completely unaware of his family’s tragic history.

For over a century, our family believed that Bridget had simply disappeared into America.

Michael told Margaret during an emotional meeting at the historical society.

My great-grandfather Patrick never stopped looking for her.

Never stopped hoping she would write or come home to Ireland.

He died not knowing what had happened to his sister.

Margaret worked with the Chicago Police Department to create a comprehensive report documenting their findings.

While no criminal charges could be filed due to the passage of time and the deaths of all involved parties, the report would serve as an official record of the crimes committed and the victims who had been forgotten by history.

The photograph itself presented an ethical dilemma.

While it was horrific evidence of murder, it was also the only proof of what had happened to Bridget Sullivan and potentially other victims.

After extensive consultation with ethicists, victim advocacy groups, and the families of the deceased, the decision was made to preserve the photograph in the police archives while creating a memorial that would honor the victims without exploiting their suffering.

Father McKenna, they learned, had continued his advocacy work until his death in 1923.

His private papers revealed that he had never stopped believing that justice would eventually be served for the missing women.

In one of his final diary entries, he had written.

Though evil may flourish for a time in darkness, truth has a way of eventually coming to light, “I pray that someday these innocent souls will receive the justice they deserve.

” 6 months after Margaret first noticed the disturbing detail in the Whitmore family photograph, a memorial service was held at St.

Patrick’s Church in Chicago.

The service honored Bridget Sullivan and 11 other young immigrant women who had been identified as likely victims of the society’s trafficking ring.

Their names, previously known only to their grieving families, were finally spoken aloud and remembered by their community.

The case had attracted international attention, particularly in Ireland, where the story of Bridget Sullivan and the other victims resonated deeply with families whose ancestors had immigrated to America seeking better lives.

The Irish government officially commended Margaret and the Chicago Police Department for their work in uncovering the truth about these forgotten crimes.

Margaret had continued her research, working with colleagues in Argentina to trace what had happened to the Witmore family after they fled Chicago.

They discovered that James Whitmore, living as Santiago Blanco, had died in Buenoses in 1923.

His wife, Elena, had died in 1931, and their children had lived comfortable lives as respected members of Argentine society, never facing consequences for their father’s crimes.

The photograph itself was eventually displayed in a special exhibition at the Chicago Historical Society titled Hidden Truths: Uncovering Forgotten Crimes Through Historical Evidence.

The exhibition drew thousands of visitors and sparked conversations about how many other historical injustices might remain hidden in archives and family collections around the world.

“This case reminds us that history is not just dates and facts,” Margaret told reporters at the exhibition’s opening.

Every photograph, every document, every preserved artifact has the potential to tell us something important about the human experience.

Sometimes that means uncovering beautiful stories of triumph and love.

Sometimes, as with the Witmore photograph, it means giving voice to victims who were silenced by those in power.

Detective Rodriguez reflected on the case’s impact during her retirement ceremony years later.

We couldn’t arrest anyone or bring the perpetrators to trial, she said.

But we could ensure that their victims were remembered and that the truth was finally told.

Sometimes that’s the only justice possible.

But it’s still justice.

The corner of the Witmore parlor, once hiding a dark secret, had finally revealed its truth.

not just about one family’s crimes, but about the vulnerability of immigrants in early America and the importance of never giving up the search for justice, no matter how much time has passed.

News

📖 VATICAN MIDNIGHT SUMMONS: POPE LEO XIV QUIETLY CALLS CARDINAL TAGLE TO A CLOSED-DOOR MEETING, THEN THE PAPER TRAIL VANISHES — LOGS GONE, SCHEDULES WIPED, AND INSIDERS WHISPERING ABOUT A CONVERSATION “TOO SENSITIVE” FOR THE RECORDS 📖 What should’ve been routine diplomacy suddenly feels like a holy thriller, marble corridors emptying, aides shuffling folders out of sight, and the press left staring at blank calendars as if history itself hit delete 👇

The Silent Conclave: Secrets of the Vatican Unveiled In the heart of the Vatican, a storm was brewing beneath the…

🙏 MIDNIGHT SHIELD: CARDINAL ROBERT SARAH URGES FAMILIES TO WHISPER THIS NEW YEAR PROTECTION PRAYER BEFORE THE CLOCK STRIKES, CALLING IT A SPIRITUAL “ARMOR” AGAINST HIDDEN EVIL, DARK FORCES, AND UNSEEN ATTACKS LURKING AROUND YOUR HOME 🙏 What sounds like a simple blessing suddenly feels like a holy alarm bell, candles flickering and doors creaking as believers clutch rosaries, convinced that one forgotten prayer could mean the difference between peace and chaos 👇

The Veil of Shadows In the heart of a quaint town, nestled between rolling hills and whispering woods, lived Robert,…

🧠 AI VS. ANCIENT MIRACLE: SCIENTISTS UNLEASH ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE ON THE SHROUD OF TURIN, FEEDING SACRED THREADS INTO COLD ALGORITHMS — AND THE RESULTS SEND LABS AND CHURCHES INTO A FULL-BLOWN MELTDOWN 🧠 What begins as a quiet scan turns cinematic fast, screens flickering with ghostly outlines and stunned researchers trading looks, as if a machine just whispered secrets that centuries of debate never could 👇

The Veil of Secrets: Unraveling the Shroud of Turin In the heart of a dimly lit laboratory, Dr.Emily Carter stared…

📜 BIBLE BATTLE ERUPTS: CATHOLIC, PROTESTANT, AND ORTHODOX SCRIPTURES COLLIDE IN A CENTURIES-OLD SHOWDOWN, AND CARDINAL ROBERT SARAH LIFTS THE LID ON THE VERSES, BOOKS, AND “MISSING” TEXTS THAT FEW DARED QUESTION 📜 What sounds like theology class suddenly feels like a conspiracy thriller, ancient councils, erased pages, and whispered decisions echoing through candlelit halls, as if the world’s most sacred book hid a dramatic paper trail all along 👇

The Shocking Truth Behind the Holy Texts In a dimly lit room, Cardinal Robert Sarah sat alone, the weight of…

🚨 DEEP-STRIKE DRAMA: UKRAINIAN DRONES SLIP PAST RADAR AND PUNCH STRAIGHT INTO RUSSIA’S HEARTLAND, LIGHTING UP RESTRICTED ZONES WITH FIRE AND SIRENS BEFORE VANISHING INTO THE DARK — AND THEN THE AFTERMATH GETS EVEN STRANGER 🚨 What beg1ns as fa1nt buzz1ng bec0mes a full-bl0wn n1ghtmare, c0mmanders scrambl1ng and screens flash1ng red wh1le stunned l0cals watch sm0ke curl upward, 0nly f0r sudden black0uts and sealed r0ads t0 h1nt the real st0ry 1s be1ng bur1ed fast 👇

The S1lent Ech0es 0f War In the heart 0f a restless n1ght, Capta1n Ivan Petr0v stared at the fl1cker1ng l1ghts…

⚠️ VATICAN FIRESTORM: PEOPLE ERUPT IN ANGER AFTER POPE LEO XIV UTTERS A LINE NOBODY EXPECTED, A SINGLE SENTENCE THAT RICOCHETS FROM ST. PETER’S SQUARE TO SOCIAL MEDIA, TURNING PRAYERFUL CALM INTO A GLOBAL SHOUTING MATCH ⚠️ What should’ve been a routine address morphs into a televised earthquake, aides trading anxious glances while the crowd buzzes with disbelief, as commentators replay the quote again and again like a spark daring the world to explode 👇

The Shocking Revelation of Pope Leo XIV In a world that often feels chaotic and overwhelming, Pope Leo XIV emerged…

End of content

No more pages to load