Emma Brooks adjusted her computer screen, squinting at the sepia toned photograph that had arrived at the Pennsylvania Historical Society three days earlier.

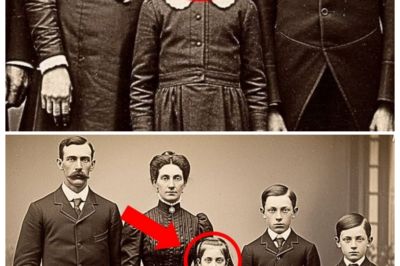

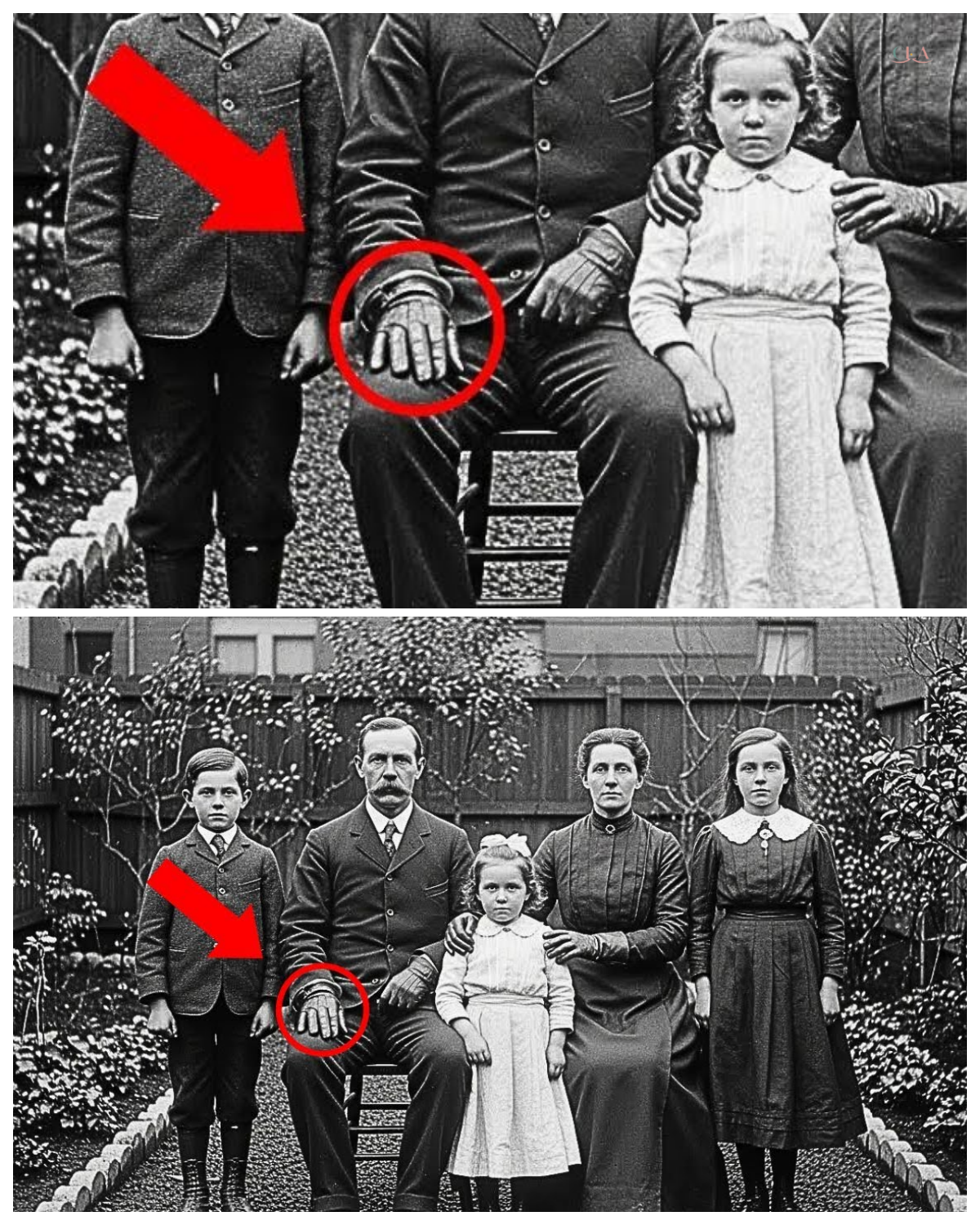

The image showed a family of five standing in a modest garden, their faces frozen in the stern expressions common to early 20th century portraits.

The father stood at the center, one hand resting on his wife’s shoulder, the other hanging stiffly at his side.

Three children flanked them, the youngest barely tall enough to reach her mother’s waist.

The photograph had been donated by Katherine Miller, an elderly woman from Pittsburgh who claimed it showed her great-grandparents.

Emma had seen hundreds of similar images during her 15 years as a photographic historian.

But something about this one nagged at her.

Perhaps it was the quality of the original print, remarkably well preserved despite its age, or the intensity in the father’s eyes that seemed to pierce through more than a century of distance.

She began the restoration process methodically, scanning the photograph at the highest resolution her equipment allowed.

The machine hummed softly as it captured every microscopic detail, transforming the physical image into millions of digital pixels.

Emma watched as the photograph appeared on her screen, revealing textures and nuances invisible to the naked eye.

As she zoomed in to examine potential damage and fading, Emma’s attention was drawn to the man’s hands.

He wore dark leather gloves, formal and pristine, buttoned carefully at the wrists.

She magnified the image further, focusing on the right glove.

The enhanced resolution revealed the intricate stitching, the slight wear at the fingertips, the way the leather creased at the knuckles.

Then she saw it between two seams near the base of the thumb.

Something light colored protruded slightly.

At first, Emma thought it might be a defect in the photograph or a speck of dust on the original print.

She adjusted the contrast and sharpened the image.

Her breath caught in her throat.

It was paper.

A small folded piece of paper deliberately tucked between the seams of the glove.

Emma leaned closer to the screen, her heart beginning to race.

In all her years examining historical photographs, she had never seen anything quite like this.

The paper appeared to have writing on it, though the angle and the fold made it impossible to read the actual words.

Why would someone hide a note in their glove during a formal family portrait? What could be so important that it needed to be concealed yet preserved in this way? She reached for her phone, her hands trembling slightly.

This discovery demanded further investigation, and she knew exactly where to start.

Katherine Miller answered the door of her small Pittsburgh home wearing a cardigan despite the mild September afternoon.

Her eyes still sharp at 87 brightened when she saw Emma standing on her porch with a leather portfolio under her arm.

“Miss Brooks, I wasn’t expecting you to come all the way here,” Catherine said, ushering Emma inside.

“The living room was cluttered with photographs, albums stacked on every available surface, generations of faces watching from frames on the walls.

” Emma settled into an armchair and carefully opened her portfolio, withdrawing printed enlargements of the photograph.

Mrs.

Miller, I need to ask you about the family in this portrait.

You said they were your great-grandparents.

Thomas and Clara Reed.

Yes.

The photograph was taken in the summer of 1903, right in their backyard on Malbury Street.

Catherine pointed to each figure.

That’s Thomas in the center.

Clara beside him.

The children are William, the oldest, then Sarah, and little Margaret at the front.

Emma placed the enlargements on the coffee table.

What can you tell me about Thomas? What did he do for a living? Catherine’s expression grew thoughtful.

He was an engineer with the Pennsylvania Railroad, worked on the locomotives and maintenance schedules.

My grandmother Sarah always said he was brilliant with machinery, could fix anything.

She paused, her fingers tracing the edge of one photograph.

But she also said he was troubled toward the end, worried about something he wouldn’t discuss with the family.

The end? Emma asked carefully.

Thomas died in February 1904, just 7 months after this photograph was taken.

There was an accident at the railard.

At least that’s what the company claimed.

Catherine’s voice dropped slightly.

My grandmother never believed it.

She was only 12 when it happened, but she remembered her mother crying at night, saying things didn’t make sense.

Clara kept a diary.

I have it somewhere in the attic if you’re interested.

Emma felt her pulse quicken.

I’m very interested, Mrs.

Miller.

But first, I need to show you something I discovered during the restoration.

She pointed to the enhanced image of Thomas’s glove.

Do you see this right here between the seams? Catherine leaned forward, squinting at the image.

Her hand went to her mouth.

Is that paper? Yes, there’s something written on it, but I can’t make out the words from the photograph alone.

Did your grandmother ever mention Thomas hiding anything? Any family stories about secrets or documents? Catherine sat back heavily in her chair, her face pale.

There was always something, a mystery that haunted my grandmother her whole life.

She said Thomas told Clara the night before he died that if anything happened to him, she should look at the photograph, their family photograph.

Clara searched everywhere behind the frame and the backing, but never found anything.

Because, Emma said softly, no one thought to look inside the glove itself.

The attic of Catherine’s home smelled of old paper and cedar.

Dust moes danced in the afternoon light, streaming through a small window as Emma and Catherine carefully sorted through boxes of family documents.

Catherine moved slowly, her arthritic hands gentle with the fragile artifacts of her ancestors lives.

Here, Catherine said finally, lifting a small leatherbound book from a cardboard box.

Clara’s diary.

She started writing in it after Thomas died.

My grandmother gave it to me before she passed.

Emma accepted the diary with reverent care, feeling the weight of history in her hands.

The leather was cracked with age.

The pages yellowed, but still intact.

She opened to the first entry, dated March 15th, 1904, just weeks after Thomas’s death.

Clara’s handwriting was elegant, but trembling.

The ink faded to brown.

Emma read aloud.

They tell me it was an accident.

A coupling failure, they said, and Thomas was in the wrong place.

But I know my husband.

He was never careless.

He was afraid these last months, though he tried to hide it from the children.

At night, he would wake from nightmares, muttering about numbers and dates that made no sense to me.

Emma turned the pages carefully, scanning entry after entry.

Clara wrote about her grief, her struggles to support three children alone, her suspicions about the railroad company.

Then, dated August 2nd, 1904, Emma found what she was looking for.

“Listen to this,” Emma said, her voice tight with excitement.

Clara writes, “I found Thomas’s words in my memory today.

” The night before he died, he held my hands and said, “Remember the garden photograph, Clara? Remember where I’m looking? If they come for me, you’ll know I was right.

” I asked what he meant, but he only kissed my forehead and said the truth was in plain sight.

Catherine’s eyes were wet.

She never understood what he meant.

“But we might,” Emma said.

She pulled out her laptop and opened the highresolution scan of the photograph.

“Look at Thomas’s eyes.

Where is he looking?” They both leaned over the screen.

Unlike the rest of his family, who stared beautifully at the camera, Thomas’s gaze was directed slightly downward and to the left.

His expression, which Emma had initially read as stern, now seemed deliberate and purposeful.

“He’s looking at his own hand,” Catherine whispered.

at the glove.

Emma nodded slowly.

He was telling Clara where to find the truth, but she was looking for something behind the photograph, not in the photograph itself.

The message was literally in his hands the entire time.

She continued reading through Clara’s diary, finding more fragments that painted a troubling picture.

Thomas had been documenting something at the railroad.

He came home late, spent hours writing in a notebook he kept hidden.

He told Clara that men were dying unnecessarily, that someone needed to speak up.

What was on that paper in his glove? Catherine asked quietly.

Emma looked at the enhanced image again, studying the barely visible edge of folded paper.

I don’t know yet, but I think Thomas Reed was trying to protect evidence of something the railroad wanted buried.

And I think we need to find out what.

The Pennsylvania Railroad historical archives occupied a converted warehouse in downtown Pittsburgh.

Its brick walls lined with filing cabinets and storage boxes containing decades of company records.

Emma had called ahead, explaining her research to the archivist, a meticulous man named David Chen, who seemed genuinely intrigued by her quest.

“Records from 1903 and 1904,” David said, leading Emma through narrow aisles between towering shelves.

“We have employment files, accident reports, maintenance logs.

What specifically are you looking for?” “Anything related to Thomas Reed.

He was an engineer who died in February 1904.

The company called it an accident, but his family had doubts.

” Emma followed David to a section marked with faded labels dating back to the turn of the century.

David pulled down several boxes, setting them on a research table.

Accident reports from that period should be in here.

The railroad was required to document all workplace incidents, though the records vary in detail depending on who filed them.

Emma opened the first box, her fingers trembling slightly as she sorted through brittle documents.

The paperwork was extensive.

Injury reports, equipment failures, insurance claims.

The railroad had been a dangerous place to work in 1904.

That much was clear.

She found references to crushed limbs, derailments, boiler explosions.

Each report was clinical, reducing human tragedy to a few typed lines.

Then she found Thomas’s file.

The accident report was dated February 18th, 1904.

According to the document, Thomas Reed had been performing a routine inspection in the railard when a coupling between two freight cars failed unexpectedly.

He was caught between the cars and died at the scene.

The report was signed by a supervisor named Robert Hayes and counter signed by the yard manager.

Emma read it twice, then looked up at David.

This seems straightforward enough.

Why would Clara doubt it? May I? David asked, reaching for the document.

He studied it carefully, his trained eye-catching details Emma had missed.

See here, the report was filed 3 days after the incident.

That’s unusual.

Most accident reports were filed within hours, especially for fatalities.

The company needed documentation for insurance purposes.

He pointed to another detail.

And look at this signature.

Robert Hayes.

I’ve seen his name before.

David moved to his computer, typing rapidly.

Hayes was promoted to regional safety director in March 1904, less than a month after Thomas’s death.

Before that, he’d been a mid-level supervisor with an unremarkable record.

Emma felt a chill run down her spine.

A promotion right after a fatal accident he supervised.

It does raise questions, David agreed.

He returned to the boxes, pulling out additional files.

Let me check something else.

If Thomas was documenting safety issues, there might be other reports from that period showing a pattern.

They worked in silence for the next hour, Emma taking notes while David retrieved file after file.

A picture began to emerge, disturbing in its implications.

Between January 1903 and February 1904, there had been 17 workplace deaths in the Pittsburgh railards.

Most were attributed to equipment failures or worker error.

The frequency seemed abnormally high.

17 deaths in 14 months, Emma said softly.

That’s more than one per month.

David nodded grimly.

And look at the causes.

Seven coupling failures, four brake malfunctions, three derailments due to track defects, two boiler explosions, one fall from a signal tower.

The coupling failures alone, that’s what killed Thomas.

Emma finished.

Emma spent the next three days at the archives building a timeline of accidents and deaths at the Pennsylvania Railroads Pittsburgh operations.

David had given her access to maintenance logs, inspection reports, and internal memoranda from 1902 through 1905.

The documents painted a damning picture of negligence and cost cutting that had preceded the spike in fatal accidents.

She created a spreadsheet on her laptop, entering data methodically, dates, names, causes of death, equipment involved, supervisors present.

As the columns filled, patterns emerged that made her stomach tighten with anger.

The coupling failures that had killed seven men, including Thomas, all involved the same type of equipment.

Model C47 automatic couplers manufactured by a company called Midwest Iron Works.

Internal memos from 1902 showed that railroad engineers, Thomas among them, had flagged potential design flaws in the C-47s.

The couplers were prone to stress fractures in cold weather, making them unreliable during Pittsburgh’s harsh winters.

Yet, the railroad had continued using them, apparently, because switching to a more expensive but safer alternative would have required significant capital investment.

A memo from the purchasing department dated November 1902 explicitly stated that replacement of existing C-47 inventory is not financially justified at this time.

Emma found Thomas’s name in another document, a maintenance report from January 1904, one month before his death.

He had inspected a freight car and noted severe wear on coupling mechanism recommend immediate replacement.

The report was stamped deferred in red ink.

Three weeks later, Thomas was dead, killed by a coupling failure.

But there was more.

Emma discovered that after Thomas’s death, the railroad had quietly begun replacing all C-47 couplers with the safer alternative.

By June 1904, none remained in service.

The fatal accidents had dropped dramatically.

Between March 1904 and March 1905, there were only two workplace deaths in the Pittsburgh yards, both attributed to causes unrelated to equipment failure.

“They knew,” Emma said aloud, sitting back from her computer.

The archives reading room was empty, except for David, who looked up from his own work.

knew what the railroad knew the couplers were defective.

They knew men were dying because of faulty equipment.

And after Thomas died, they fixed the problem.

They replaced everything.

Emma’s hands were shaking.

Thomas must have been documenting this.

That’s what he was afraid of.

He knew, and they knew he knew.

David came over to examine her spreadsheet, his expression growing dark as he absorbed the information.

This is more than negligence, Emma.

If Thomas had documentation proving the company knowingly used defective equipment despite safety warnings, they would have been liable for wrongful deaths, lawsuits, criminal charges, possibly.

Emma thought of Clara’s diary, the entry about Thomas saying men were dying unnecessarily.

He was collecting evidence.

That’s why he was afraid.

That’s why Clara thought his death wasn’t an accident.

“Do you think they killed him?” David asked quietly.

Emma looked at the photograph of Thomas Reed on her laptop screen.

at his somber face and the deliberate downward glance toward his gloved handed.

I think they might have, or at least they created the circumstances that led to his death.

And I think whatever was in that glove, that piece of paper, might have been the proof.

She needed to see the original photograph, not just the digital scan.

She needed to examine the actual paper hidden in Thomas’s glove.

But the photograph was sealed in an archival sleeve at the historical society, preserved as a historical artifact.

Opening it, possibly damaging it to extract a piece of paper from a glove worn by a man who had been dead for 120 years, would require permission and careful planning.

I need to go back to Catherine, Emma said, closing her laptop.

And we need to figure out how to open that glove without destroying the photograph.

Catherine sat in the conservation laboratory of the Pennsylvania Historical Society.

Her hands clasped tightly in her lap as she watched Emma and a conservator named Lisa prepare to examine the photograph.

The original print lay on a specialized table under bright neutral lighting protected by a sheet of archival myar.

I’ve never done anything quite like this, Lisa admitted, adjusting her magnifying headset.

We’re essentially performing archaeological work on a photograph.

If there really is paper inside that glove, it’s been compressed there for over a century.

Removing it without damage will be delicate.

Emma had spent two days convincing the society’s director to approve the procedure.

The photograph was technically Catherine’s property, donated with the understanding that it would be preserved, but the potential historical significance of the hidden paper had finally persuaded him to allow the investigation.

The paper appears to be tucked between the outer leather and the lining of the glove.

Lisa continued examining the photograph through a high-powered magnifier.

It’s not actually inside the glove itself, but in a seam that’s been partially opened.

You can see here, she pointed with a wooden stylus.

Uh, where the stitching has been deliberately loosened.

Thomas did that himself, Catherine said softly.

He opened his glove, put the paper inside, and then posed for the photograph knowing it would be preserved.

Lisa nodded.

The question is whether we can recover the paper without damaging the photographic emulsion.

The gelatin silver print is in remarkable condition, but it’s still fragile.

If the paper is adhered to the surface or if removing it tears the emulsion.

What do you recommend? Emma asked.

We use a process called humidification.

We create a controlled humidity chamber that will slowly relax both the photographic paper and whatever is tucked in that glove.

It might take several hours, but it’s our best chance of extracting the paper intact.

They work carefully setting up a sealed chamber with precise humidity controls.

The photograph was suspended on a mesh screen allowing moisture to penetrate evenly from all sides.

Lisa monitored the process constantly, checking temperature and humidity levels, watching for any signs of damage to the print.

3 hours later, she examined the photograph again under magnification.

It’s working.

I can see the paper separating slightly from the glove.

Give it another hour.

Catherine had brought sandwiches, though no one felt much like eating.

They sat in the laboratory’s small break room drinking coffee and talking about Thomas and Clara, about the children who grew up without their father, about the secrets that had remained hidden for so long.

My grandmother Sarah carried the weight of this her whole life.

Catherine said she never stopped believing that something terrible had happened to her father.

She died in 1989, 35 years ago, still not knowing the truth.

I wish she could have lived to see this.

Emma reached across the table and squeezed Catherine’s hand.

She’d be proud that you didn’t give up, that you preserve these documents and photographs.

Without that, we’d never know what Thomas tried to tell us.

When Lisa finally called them back to the laboratory, the photograph had been removed from the humidity chamber and placed back on the examination table.

Using tweezers and a specialized tool that looked like a tiny dental pick, she carefully teased at the edge of the paper visible in the glove’s seam.

Emma held her breath as Lisa worked, each movement precise and controlled.

Slowly, infinitesimally, the paper began to emerge.

It was folded tightly, compressed by time and pressure, into a small, hard rectangle no larger than a postage stamp.

Got it,” Lisa whispered, lifting the paper free.

She placed it on a glass plate and stepped back, exhaling deeply.

“That’s the most stressful extraction I’ve ever performed.

” The paper sat on the glass, still folded, slightly discolored, but intact.

Emma could see writing on the exposed surface, faded, but legible.

Numbers and letters in Thomas’s careful hand.

“Now we unfold it,” Lisa said very, very carefully.

The paper, once fully unfolded, measured approximately 2 in square.

Thomas had written on both sides in pencil, the graphite faded, but still readable under magnification.

Emma, Catherine, and Lisa crowded around the examination table, their eyes fixed on the cramped handwriting that had been hidden for 120 years.

The front side contained what appeared to be coordinates 40 deg 6 3 N 79 to 58 47W.

Below that, a date, January 15th, 1904.

And beneath the date, a single word, evidence.

I.

The reverse side held more information written in a smaller, more hurried script.

East foundry wall, 12 ft from northeast corner, 18 in below grade.

May God protect my family if I fail.

Emma felt tears prick her eyes.

Thomas had known he was in danger.

He had known that what he was doing might cost him his life, and he had hidden this information in the one place he trusted it would be preserved.

in a family photograph that Clara would cherish and protect forever.

“Those coordinates,” David said.

He had been called in as soon as the paper was extracted.

“Let me check them,” he typed rapidly on his laptop, then turned the screen to show them.

“That’s a location in Pittsburgh near the old Pennsylvania Railroad Foundry Complex.

The buildings are mostly demolished now, but in 1904, that was where they manufactured and repaired equipment.

” “The East Foundry Wall,” Emma read again.

“He buried something there, the evidence he’d been collecting.

” Catherine’s voice was barely a whisper.

Can we find it after all this time? Lisa carefully placed the unfolded paper in an archival sleeve, documenting it with photographs from every angle.

This needs to be preserved properly.

But yes, you have the information now.

The question is whether anything remains at those coordinates after 120 years.

Emma was already making plans, her mind racing.

The foundry complex.

What’s there now? David pulled up property records and satellite imagery.

Most of it was demolished in the 1970s when the railroad moved operations.

The land is now a mixture of abandoned lots, a small industrial park, and a community garden.

But look, he zoomed in on the satellite view.

This section here shows what looks like a remaining foundation wall.

It’s overgrown and partially collapsed, but it’s still there.

The east wall, Emma breathed, it survived.

The coordinates Thomas had written pointed to a spot that, according to modern mapping, was now part of an overgrown vacant lot adjacent to the community garden.

The property was owned by the city, abandoned and forgotten, waiting for redevelopment that had never come.

We need permission to excavate, Emma said.

And we need to do this properly.

Document everything.

If there’s evidence buried there, documents, photographs, whatever Thomas hid, it needs to be handled as a historical find.

Catherine stood up, her aged frame suddenly animated with purpose.

How long will that take? The permissions, the planning? Usually weeks or months, David admitted.

We’d need to apply to the city, get approval from the historical society, possibly involve law enforcement if we’re uncovering evidence of a crime.

Thomas waited 120 years.

Catherine interrupted, her voice firm.

But I’m 87 years old.

I don’t have months or years.

I need to know what my great-grandfather died protecting.

I need to know the truth he never got to tell.

Emma looked at the elderly woman, seeing the determination in her eyes that must have burned in Thomas’s as well.

the same stubborn courage that had driven him to risk everything for justice.

“Then we’ll make it happen,” Emma said.

“As quickly as we possibly can.

” Two weeks later, Emma stood in the overgrown lot beside the remnants of the old foundry wall, watching as a small excavation team prepared their equipment.

The process of getting permission had been accelerated by media interest.

When the story of Thomas Reed and his hidden message broke in the Pittsburgh Papers, public pressure had convinced city officials to fasttrack the necessary approvals.

Catherine sat in a folding chair nearby, wrapped in a blanket against the cool October morning.

News crews had gathered at the perimeter of the site, cameras ready to document whatever was found.

The story had captured imaginations.

A railroad engineers century old secret hidden in a family photograph leading to buried evidence of corporate wrongdoing.

The lead archaeologist, Dr.

Sarah Chen from the University of Pittsburgh, approached Demo with a ground penetrating radar unit.

We’ve completed the initial scan.

There’s definitely something down there.

approximately 18 inches below the current grade level, right where your coordinates indicated.

It’s metallic, probably a box or container of some kind.

Emma’s heart raced.

How long until you can reach it? We’ll work carefully.

This is a historical excavation now, and we need to document every layer.

A few hours, maybe.

Sarah signaled to her team, who began marking out a careful grid around the coordinates.

The work progressed slowly, deliberately.

They removed soil and controlled layers, sifting through each shovel full for any artifacts or clues.

The foundry wall loomed beside them, its bricks crumbling and covered with a century of vines.

A silent witness to what Thomas Reed had done on that January day in 1904.

48 in down, a team member’s trowel struck something solid with a distinctive metallic clink.

“We’ve got it,” Sarah called out.

The team worked even more carefully now, brushing away soil with soft tools to expose what lay beneath.

Slowly, a shape emerged.

a metal box roughly 12 in long and 8 in wide, sealed with what appeared to be wax around the edges.

It took another hour to fully excavate and remove the box.

Sarah lifted it carefully, cradling it like something precious and fragile.

It’s heavy.

There’s definitely something substantial inside.

They moved to a folding table that had been set up under a tent away from the news cameras.

Catherine rose from her chair and approached, Emma supporting her elbow.

The box sat on the table, covered with dirt and rust, but remarkably intact.

Its seal still unbroken after 120 years underground.

Should we open it here? One of Sarah’s assistants asked.

Yes, Catherine said firmly.

Whatever Thomas buried, he meant for it to be found.

Open it.

For Sarah used specialized tools to carefully break the wax seal and work open the corroded latch.

The lid resisted, then gave way with a groan of protesting metal.

She lifted it slowly, revealing the contents.

Inside, protected by an inner layer of oil cloth, was a leatherbound notebook.

Beside it were several folded documents, a small box of photographic plates, and a sealed envelope addressed in Thomas’s handwriting.

To whom it may concern, the truth about the Pennsylvania Railroad.

Uh, Emma felt tears streaming down her face as Sarah carefully removed the notebook, opening it to the first page.

Thomas’s handwriting covered the page in neat columns, recording dates, equipment numbers, maintenance reports, and names.

The names of men who had died.

He documented everything, Emma whispered.

Every accident, every ignored safety warning, every decision to prioritize profit over workers’ lives.

This is the evidence he died trying to preserve.

Catherine reached out with trembling hands, touching the notebook gently.

My great-grandfather was a hero.

He tried to save them.

Sarah turned the pages carefully, revealing entry after entry of meticulous documentation, sketches of defective equipment, copies of ignored maintenance requests, calculations showing the cost difference between safe and unsafe couplers, notes from conversations with dying colleagues who made Thomas promise to tell their stories.

The envelope contained a letter written in Thomas’s hand and dated February 17th, 1904, the day before he died.

Sarah opened the envelope with careful precision, sliding out several pages of writing paper that had yellowed with age but remained remarkably preserved.

The team gathered around as Emma read Thomas’s letter aloud, her voice breaking at times with emotion.

My name is Thomas Reed, and if you are reading this, then I have failed to deliver this testimony while living.

I write this on February 17th, 1904, knowing that tomorrow I must confront the men whose negligence has killed 17 of my brothers in the railroad yards over the past 14 months.

Emma paused, looking at Catherine, whose face was wet with tears.

She continued reading.

I am an engineer with the Pennsylvania Railroad, and I have watched good men die because our company chose profit over safety.

The coupling mechanisms manufactured by Midwest Iron Works are defective.

We have known this since 1902 when the first stress fractures appeared during cold weather operations.

I reported these concerns to my supervisors.

Others reported them as well.

We were told that replacement costs were too high, that we should work more carefully, that the accidents were due to operator error.

The letter detailed specific incidents, naming victims, and describing how each death could have been prevented.

Thomas had kept careful records, documenting every warning that had been ignored, every maintenance request that had been denied, every conversation in which supervisors had dismissed safety concerns.

I have collected evidence, maintenance logs, correspondence, photographs of defective equipment, sworn statements from other workers.

This evidence proves that the Pennsylvania Railroad knowingly used dangerous equipment despite repeated warnings about its failures.

They valued the cost savings of not replacing the couplers more than they valued our lives.

Thomas wrote about his family, about his fear of what speaking out might cost them.

My wife Clara knows I am troubled, though I have not told her the details.

I do this to protect her.

If something happens to me, I pray she will be cared for.

William, Sarah, and Margaret, my children, deserve to grow up knowing their father tried to do what was right.

The letter concluded with specific accusations against three railroad executives by name, including the supervisor, Robert Hayes, who had signed Thomas’s accident report and been promoted shortly after.

Thomas identified them as having direct knowledge of the coupler defects and having made deliberate decisions to continue using them despite the risk to workers.

Tomorrow, I will present this evidence to the regional safety director and demand immediate action.

I have made copies of the most critical documents and hidden them in this box, buried where I hope truth seekers will eventually find them.

I have also left a clue for Clara in our family photograph, though I hope she never needs to use it.

The final lines were devastating in their presence.

If I do not survive to see justice done, I trust that someday someone will find this testimony and hold accountable those who valued money more than men’s lives.

To the 17 who have died, I have tried to honor your memory.

To my family, forgive me if my courage fails or if my actions bring hardship upon you.

I love you more than words can say.

Thomas Reed, February 17th, 1904.

The silence that followed was profound.

Even the news crews at the perimeter seemed to sense the weight of the moment, their cameras quiet and still.

Catherine broke the silence, her voice strong despite her tears.

Did he confront them? The next day, Emma consulted the notebook, turning to the final entries.

Yes, he went to the railroad offices on February 18th.

According to his notes, he presented his evidence to the safety director and demanded an emergency meeting with senior management.

They scheduled a meeting for later that afternoon at the railards supposedly to inspect the equipment together.

And that’s when he died,” Catherine said quietly.

The accident report says he was killed during a coupling inspection at 3:47 p.

m.

,” Emma confirmed.

But according to his notebook, the meeting was scheduled for 3:30.

David, who had been photographing and documenting everything, spoke up.

He died 17 minutes into a meeting where he was presenting evidence of criminal negligence.

That’s not a coincidence.

Mr.

3 months later, Emma stood in a conference room at the University of Pittsburgh, presenting the findings of her research to a panel of historians, legal scholars, and journalists.

The story of Thomas Reed had grown far beyond a single photograph and a hidden note.

It had become a case study in corporate accountability, worker safety, and the courage of ordinary people standing against institutional power.

The university had created a digital archive of all the materials found in Thomas’s buried box.

His notebook had been conserved and digitized.

Every page made available to researchers and the public.

The photographic plates contained images of defective equipment, workers injuries, and unsafe working conditions.

Visual evidence that corroborate Thomas’ written testimony.

Legal historians had analyzed the documents and concluded that Thomas’ evidence would have been sufficient to bring criminal charges against several railroad executives in 1904.

The deliberate use of known defective equipment that resulted in worker deaths constituted at minimum criminal negligence and possibly manslaughter.

What Thomas Reed documented, Emma explained to the assembled panel, was not an isolated incident, but a systemic pattern of prioritizing profit over human life.

His courage in collecting this evidence, knowing the personal risk involved, represents the best of labor activism during an era when workers had few legal protections.

The story had prompted modern investigations as well.

Historians had discovered that Robert Hayes, the supervisor who signed Thomas’s accident report and was promoted shortly after, had received a substantial bonus in March 1904, the same month the railroad began quietly replacing all the defective couplers.

The paper trail suggested a coverup that had succeeded for 120 years.

Catherine attended the presentation, sitting in the front row with several of her own grandchildren.

The Reed family had grown over the generations, and many had traveled to Pittsburgh to honor their ancestor.

Thomas’s story had become their story, a source of pride and identity.

My great-grandfather’s truth was hidden for over a century, Catherine said when Emma invited her to speak.

But it was never lost.

He made sure of that.

He protected it in the only way he could, trusting that love and memory would preserve what he couldn’t protect in life.

He was right.

The university had commissioned a memorial to be installed at the site where Thomas’s evidence had been buried.

It featured a bronze plaque with his photograph, the same photograph that had revealed his secret and an inscription that quoted his letter.

I trust that someday someone will find this testimony and hold accountable those who valued money more than men’s lives.

Local labor unions had embraced Thomas’ story, making him a symbol of early workers rights advocacy.

The Pennsylvania Railroad was long defunct, dissolved, and absorbed into other companies decades earlier, but the lessons of what had happened in 1904 remained relevant.

Thomas’s documentation had been incorporated into labor history curricula used to teach about workplace safety regulations and the importance of whistleblower protections.

Emma had written extensively about the case, publishing articles in historical journals and popular magazines.

The photograph itself had been featured in exhibitions about early photography, labor history, and investigative methods.

But for Emma, the most meaningful outcome was simpler and more personal.

She had given Catherine closure.

The elderly woman could now tell her own grandchildren about Thomas, not as a man who died in a mysterious accident, but as someone who had fought for justice and protected his evidence with remarkable ingenuity.

The photograph that had hung in family homes for generations was no longer just a family portrait.

It was proof of courage, sacrifice, and love.

On the day of the memorial’s dedication, Emma stood beside Catherine as they looked at Thomas’s bronze likeness.

The photograph had been enlarged and etched into the metal every detail preserved, including the glove that had held his secret.

He’s finally been heard,” Catherine said softly.

“After all this time, people know what he tried to do.

” Emma nodded, thinking about the chain of preservation that had made this moment possible.

Clara, keeping the photograph despite her grief, passing it to her daughter Sarah, who gave it to Catherine, who donated it to the historical society, where Emma had noticed something no one else had seen.

Five generations connected by a single image and the truth it contained.

“His message reached us,” Emma replied.

And now it’s our responsibility to make sure it’s never forgotten.

The November wind moved through the memorial site, rustling the few remaining leaves on nearby trees.

Above them, the sky was clear and bright, and for a moment, Emma imagined Thomas standing in his garden in 1903, posing for a photograph with his family, knowing that what he held in his gloved hand might be the only testimony to survive him.

He had trusted in the future, in the possibility that someone would care enough to look closely, to ask questions, to seek truth.

He had been right to trust.

Catherine placed a single white rose at the base of the memorial, her aged hands steady.

Around them, Thomas’s descendants gathered.

Dozens of people whose lives existed because Clara had survived her husband’s death and raised their children with strength and dignity.

They carried Thomas’ legacy, not just in their DNA, but in their commitment to justice, safety, and speaking truth to power.

Emma took a final photograph of the memorial, the bronze plaque gleaming in the afternoon sun.

Thomas Reed’s face, captured in 1903, looked out at the modern world he had never lived to see.

A world where his story was finally known.

Where his courage was finally recognized.

News

Why were historians turned pale when they zoomed in on this 1887 wedding portrait? The basement archive of the Chicago Historical Museum smelled of old paper and dust, a scent that Dr. Rachel Thompson had grown to love over her 15 years as a curator. On this particular October morning in 2024, sunlight filtered weekly through the high windows, casting long shadows across rows of storage boxes, waiting to be cataloged. Rachel sat at her workstation, methodically scanning photographs from a recent estate donation. her eyes tired but alert. The collection had belonged to the Patterson family, descendants of early Illinois settlers who had finally decided to part with their ancestral archives. Most of the photographs were predictable. Stern-faced ancestors in formal poses, faded images of farmland, a few Civil War soldiers standing rigidly before the camera. Rachel had processed dozens of similar collections, and she worked efficiently, noting dates and names in her database. Then she reached a photograph that made her pause.

Why were Historians Turn Pale When They Zoomed In on This 1887 Wedding Portrait? Why were historians turned pale when…

Why Did Historians Become Pale When Enlarging the Face of the Younger Girl in This 1891 Image? The Haunting Revelation of the 1891 Portrait In the dim light of the archive room, Dr. Eleanor Hayes meticulously examined the faded photograph, its edges curling with age. The image depicted a young girl, her face innocent yet enigmatic, captured in a moment that transcended time. But as Eleanor enlarged the photograph, a chill ran down her spine. The girl’s eyes, once merely a reflection of childhood, now seemed to harbor secrets that could unravel history itself. Eleanor had dedicated her life to understanding the past, but this image was different. It was as if the girl was staring into her soul, demanding to be heard. The historians had warned her about this particular photograph, claiming it was cursed, a relic that had brought misfortune to those who dared to delve too deep. But Eleanor, driven by an insatiable curiosity, pressed on. As she zoomed in, the girl’s face transformed. The smile that once appeared sweet now twisted into something sinister.

Why Did Historians Become Pale When Enlarging the Face of the Younger Girl in This 1891 Image? The Haunting Revelation…

This 1901 studio portrait looks normal — until experts zoomed in on the child’s eyes Dr.Sarah Brennan’s hands trembled slightly as she adjusted the highresolution scanner over the faded photograph. The basement archive of the Boston Heritage Museum was cold, smelling of old paper and preservation chemicals. She had been cataloging donated Victorian photographs for 3 weeks now, and most had been unremarkable. Stiff portraits of forgotten families, their stories lost to time. This one seemed no different at first glance. A studio portrait dated 1901, stamped on the back with the name Whitmore Photography Studio, Lawrence, Massachusetts. A well-dressed couple stood rigid, the man’s hand on his wife’s shoulder. Between them sat a small girl, perhaps 6 years old, in a white-laced dress with ribbons in her dark hair. The child’s hands were folded neatly in her lap, holding a small bouquet of white liies. Sarah began the scanning process, watching as the digital image appeared on her computer screen in extraordinary detail.

This 1901 studio portrait looks normal — until experts zoomed in on the child’s eyes Dr.Sarah Brennan’s hands trembled slightly…

🚨 Greg Biffle’s last flight revealed in 60 seconds as a countdown compresses terror into heartbeats, timelines snap shut, and every routine check feels fateful while the sky turns witness to courage, pressure, and a moment that refuses to stay silent ✈️⏱️ the narrator slices time with a razor voice, hinting that when seconds decide legends, the truth doesn’t shout—it clicks, pops, and dares you to keep watching 👇

The Final Descent In the heart of the night, the engines roared like a beast awakened from slumber, echoing through…

End of content

No more pages to load