Professor David Mitchell had seen thousands of photographs from Nazi Germany.

As a history professor at Columbia University specializing in World War II, his office walls were covered with images of rallies, marches, and public ceremonies.

But on a cold October morning in 1991, while reviewing archival materials from Hamburg’s state archive, one particular photograph stopped him cold.

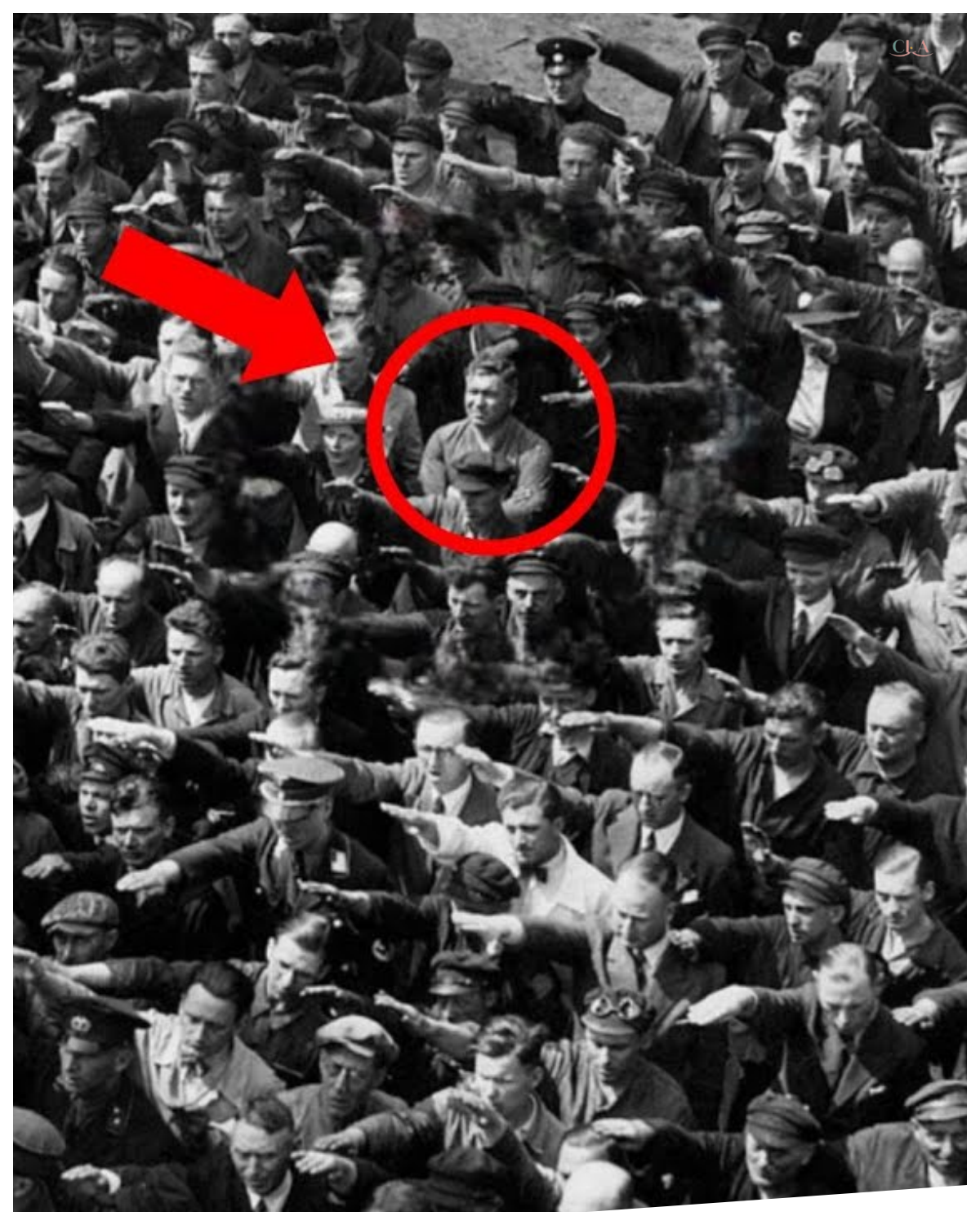

The image showed hundreds of civilian workers gathered at the Blom Plus shipyard in Hamburg, June 13th, 1936.

They were attending the launch of the horse vessel, a training vessel for the German Navy.

Shipyard employees, dock workers, foremen, engineers, ordinary working men assembled for a ceremonial event.

The scene was typical of the era.

A sea of raised arms performing the Nazi salute, faces turned towards something outside the frame, probably a Nazi official or party leader.

Row after row of identical gestures, a choreographed display of conformity and allegiance.

David had almost moved past it when something caught his eye.

He leaned closer to his desk lamp, squinting at the grainy black and white image.

In the middle of the crowd, among hundreds of outstretched arms, one man stood differently.

His arms were crossed firmly over his chest.

His face wore an expression that could only be described as defiant displeasure.

“That’s impossible,” David whispered to himself.

He had studied Nazi Germany for 23 years.

He knew the consequences of public dissent.

People disappeared for far less than refusing the Hitler salute.

Yet here was photographic evidence of someone doing exactly that, captured in broad daylight, surrounded by witnesses at an official state ceremony.

David pulled out his magnifying glass, studying every detail of the man’s face and posture.

He was young, maybe in his late 20s or early 30s, wearing a simple worker’s outfit, likely a shipyard laborer or dock employee.

His jaw was set, his eyes focused somewhere in the distance.

There was no fear in his expression, only quiet determination.

Around him, everyone else’s arms were raised.

The contrast was staggering.

It was as if someone had taken a photograph of total conformity and dropped a single act of rebellion right in the center.

David felt his hands trembling slightly as he made a photocopy of the image.

This wasn’t just another historical document.

This was evidence of something extraordinary.

One ordinary shipyard worker’s refusal to surrender his dignity even when surrounded by hundreds of his co-workers performing the Nazi salute in perfect unison.

He had no idea who this man was, what happened to him, or why he chose that moment to resist.

But David Mitchell knew with absolute certainty that he would not rest until he found out.

The investigation was about to begin.

David couldn’t sleep that night.

The image of the man with crossed arms haunted him.

He had returned to his apartment in Manhattan with copies of the photograph, spreading them across his dining table under bright lights, examining every millimeter of the frame.

The more he studied it, the more remarkable it became.

This wasn’t a blurry accidental capture.

The photograph was sharp, clear, professionally taken.

The man’s defiance was undeniable and unmistakable.

How had this image survived? How had the photographer not been forced to destroy it? How had the man himself survived what must have been immediate consequences from Nazi officials or even his fellow workers? By dawn, David had filled three pages of his notebook with questions.

He called his colleague, Dr.

Rebecca Hartman, a specialist in Nazi era documentation at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC.

“Rebecca, I need your help,” he said, his voice urgent.

“I found something extraordinary.

” 2 days later, Rebecca sat in David’s office, holding the photograph with white archival gloves.

She studied it in silence for several minutes, her expression shifting from curiosity to disbelief.

“David, do you understand what this is?” she finally asked.

a man refusing the Hitler salute at a public event in 1936.

“It’s more than that,” Rebecca said quietly.

“It’s evidence of individual resistance in a moment when resistance could mean death.

This is a civilian worker at a shipyard ceremony surrounded by hundreds of colleagues, all performing the Nazi salute.

” And he refused.

“This is this is extraordinary.

But we need to verify its authenticity.

We need to make absolutely certain this photograph hasn’t been altered or manipulated.

” They spent the next week conducting technical analysis.

They examined the grain structure, the lighting, the shadows, the photographic paper.

Every test confirmed the same conclusion.

The photograph was genuine, unmanipulated, taken in June 1936 at the Blown Plus Foss shipyard in Hamburg.

Now comes the hard part, Rebecca said.

We need to find out who he was.

David contacted the Hamburg State Archive, explaining his discovery.

The archivist, a meticulous German historian named Dr.

Klaus Brener was initially skeptical, but when David sent him high resolution scans, Klaus called back within hours.

“Uh, Professor Mitchell, this photograph has been in our collection for decades,” Klouse explained in accented English.

“But nobody noticed the man with crossed arms.

Nobody looked closely enough.

You may have discovered something that has been hiding in plain sight for over 50 years.

” “Can you help me identify him?” David asked.

“I will try,” Klaus promised.

“But it will not be easy.

That shipyard employed thousands of workers.

Many records were destroyed during the war.

And if this man was arrested or killed for his defiance, there may be no record at all.

David felt a chill run down his spine.

The man in the photograph had shown incredible courage, but courage in Nazi Germany often came with a terrible price.

“We have to try,” David said firmly.

“This man deserves to be remembered.

” The investigation consumed David’s life.

He spent every spare moment pouring over Nazi era employment records, arrest documents, and deportation lists.

Rebecca joined him, traveling between New York and Washington, coordinating with archives across Germany.

Klouse worked tirelessly in Hamburgg, searching through dusty boxes of shipyard employment files that had somehow survived the Allied bombing campaigns.

3 months into the search, they had identified hundreds of workers who were present at the ship launch ceremony.

But narrowing down which one was the man in the photograph proved nearly impossible.

The image quality, while clear enough to show his defiant posture, didn’t provide enough facial detail for definitive identification without supporting documentation.

Then Klaus found something.

Buried in a filing cabinet in the basement of Hamburg’s municipal archive was a police file from 1935.

It contained a report about a man named August who had been warned by local authorities for rasenshand, race defilement, the Nazi term for relationships between Jews and non-Jews.

The file mentions he worked at Blom plus Voss, Klaus said during a crackling international phone call.

And there’s a photograph attached to his police record.

David’s heart raced.

Can you send it? The facts arrived the next morning, David held the grainy copy up to the light, then placed it next to the shipyard photograph.

The facial features matched, the build matched, the age matched.

“Rebecca, I think we found him,” David said, his voice barely above a whisper.

“August Lan Messer.

” Over the following weeks, they pieced together the basic outline of August’s life.

He was born in 1910 in a small town in northern Germany.

He had joined the Nazi party in 1931, likely to improve his employment prospects during the economic depression.

He worked as a laborer at the Blum Plusvos shipyard.

But then the trail became complicated.

According to party records, August had been expelled from the Nazi party in 1935.

The reason cited was dishonored to the race through marriage to a Jewist.

He fell in love with a Jewish woman, Rebecca said, reading through the translated documents.

In Nazi Germany, that’s why he was standing there with his arms crossed.

He had already lost everything.

He had nothing left to lose.

David felt a profound sadness wash over him.

This wasn’t just a story of defiance.

It was a story of love, of choosing human connection over political conformity, of paying an unimaginable price for refusing to hate.

We need to find out what happened to him, David said.

And we need to find out about the woman he loved.

The investigation was no longer just academic.

It had become personal.

They were no longer searching for a name in a photograph.

They were searching for a man who had loved deeply enough to risk everything.

The woman’s name was Irma Eckler.

Finding information about her proved even more difficult than finding information about August.

Jewish records from Nazi Germany were fragmentaryary at best, deliberately destroyed at worst.

But Rebecca’s connections at the Holocaust Memorial Museum opened crucial doors.

Irma was born in 1913 in Hamburg to a Jewish family.

She met August in 1934, probably at a social gathering or through mutual friends.

By all accounts, they fell deeply in love.

In a different time, in a different place, theirs would have been an ordinary romance.

But in 1935, Germany, their relationship became criminal.

The Nuremberg laws enacted in September 1935, officially prohibited marriages and sexual relationships between Jews and non-Jews.

These laws transformed private love into public crime, turning intimate human connection into an act of political defiance.

August Denurma tried to marry anyway.

David found their marriage application submitted to Hamburg authorities in 1935 formally denied with a stamp that read application rejected racial grounds.

They didn’t give up, Rebecca said, reading through correspondence between August and various Nazi bureaucratic offices.

He kept trying.

He wrote letters, filed appeals, argued with officials.

He fought for her.

In 1935, Irma became pregnant with their first daughter.

They named her Ingred.

Without legal marriage, Ingred was classified as Micheling, mixed race, a child existing in a legal gray zone that would only become more dangerous as Nazi policies radicalized.

August’s expulsion from the Nazi party followed shortly after.

He lost his party membership, his political rights, and faced growing harassment from authorities, but he stayed with Irma.

He refused to leave her, refused to abandon his daughter, refused to comply with laws that demanded he hate the woman he loved.

In 1937, Irma gave birth to their second daughter, Irene.

By then, August was under regular surveillance.

Police reports documented his movements, his associations, his continued cohabitation with a Jewish woman.

Each report was a tightening noose.

David found arrest records showing August had been detained multiple times between 1937 and 1938, charged with Rosen.

Each time he was released after weeks or months in custody, warned, threatened, and sent back into an increasingly hostile world.

He kept going back to her, David said, overwhelmed by the courage this required.

Every time they arrested him, he went right back to Irma and his daughters.

He chose love over safety over and over again.

Rebecca was reading through witness testimonies collected after the war.

There’s a statement here from a neighbor.

She says, “August and Irma tried to flee Germany in 1938.

They made it to the Danish border, but were turned back.

They tried to escape together.

” The photograph from the shipyard suddenly carried even more weight.

That defiant stance, those crossed arms weren’t just a momentary gesture.

They represented years of resistance, years of choosing love over conformity, years of refusing to surrender his humanity even as the world demanded it.

But the documents also revealed a terrible truth.

Their story didn’t have a happy ending.

By 1938, Nazi persecution of Jews had intensified dramatically.

Cristallnak.

The night of broken glass saw synagogues burned, Jewish businesses destroyed, and thousands of Jewish men arrested and sent to concentration camps.

The net was tightening and couples like August and Irma found themselves with fewer and fewer places to hide.

David discovered that in 1938, August was arrested again, this time held for several months in Hamburgg City Prison.

When he was released, authorities gave him a stark choice.

End all contact with Irma and their children or face indefinite imprisonment.

Records from the Social Welfare Office showed that during August’s imprisonment, Irma struggled desperately to care for Ingred and Irene alone.

Jewish families were being systematically stripped of their property, their livelihoods, their basic rights.

Irma had no legal standing, no protection, no resources.

A letter dated December 1938, written in Irma’s handwriting, was preserved in municipal archives.

In it, she pleaded with authorities to allow August to visit their daughters.

The letter was formal, respectful, desperate.

My daughters ask for their father everyday.

They are innocent children.

I beg you to show mercy.

The response was a stamped rejection.

Request denied.

Despite the warnings, despite the threats, August maintained contact with his family.

But by 1939, this became impossible.

He was arrested again, this time sentenced to two and a half years in a concentration camp for dishonoring the race and refusing to comply with court orders.

He was sent to Burgamore, Klaus informed them, referencing a brutal labor camp in northern Germany.

He spent nearly two years there before being released in 1941.

Meanwhile, Irma’s situation became catastrophic.

In 1940, with August imprisoned, authorities seized Ingred and Irene, placing them in an orphanage.

Irma fought desperately to get them back.

But as a Jewish woman with no legal husband, she had no parental rights.

Rebecca found the orphanage records.

They were heartbreaking.

Notes from social workers described Irma visiting her daughters whenever allowed, bringing what little food she could find, holding them through the fence of the orphanage yard.

The last documented visit was in January 1942, Rebecca said quietly.

After that, there’s nothing.

David knew what that meant.

By 1942, the Nazi regime had moved from persecution to extermination.

Jewish families across Germany and occupied Europe were being rounded up and sent to death camps.

He found Irma’s name on a deportation list.

On January 28th, 1942, she was arrested in Hamburg and transferred to Fools prison.

From there, she was sent to the psychiatric facility at Burnberg, which the Nazis used as a killing center under their euthanasia program.

The record was cold and bureaucratic.

Irma Eckler, deceased February 1942.

Cause: Heart failure.

That’s a lie, Rebecca said bitterly.

A heart failure was the standard cover story.

She was murdered, gassed probably, or given a lethal injection.

David sat in silence, overwhelmed by grief for people he had never met, but whose story had become part of his own life.

Irma had loved August.

She had borne his children.

She had endured years of persecution.

And in the end, she had been murdered by the same regime that August had quietly defied in that photograph.

But there were still pieces missing.

What happened to August after his release from Burgermore? And what happened to Ingred and Irene, the two little girls who lost both their parents? Tracing August’s movements after his release from Burmore proved extraordinarily difficult.

By 1941, Germany was deep into World War II, and recordkeeping became chaotic and incomplete.

But David and Rebecca persisted, following every fragmentaryary lead.

August was released from the concentration camp in January 1941, probably because the Nazis needed labor for the war effort.

But he was a marked man, a former political prisoner, a man who had defied racial laws, someone considered politically unreliable.

Klaus found employment records showing August worked briefly at another Hamburg factory, but under strict surveillance.

He was prohibited from leaving the city, required to report regularly to police, and barred from any contact with his daughters, who remained in the orphanage.

A witness statement recorded in 1950 during postwar investigations came from a man named Hinrich, who had worked alongside August in 1942.

August never talked about what happened to him, but once after work, he asked me if I knew anything about the orphanage where they kept his daughters.

He wanted to know if they were being treated well.

He was desperate to know they were safe.

I told him I would try to find out, but I never did.

I was too afraid.

In September 1942, August was arrested again.

This time, the charge was attempting to contact his children.

The sentence was harsh.

Assignment to a military penal battalion, Strath Patayon 999.

These battalions were essentially death sentences.

They were composed of political prisoners, criminals, and others deemed undesirable by the regime.

sent to the most dangerous sectors of the Eastern Front with minimal equipment and training.

Expected to die in combat, David found August’s military assignment papers, he was sent to Croatia in early 1943, attached to a unit fighting Yuguslav partisans in the mountains.

The conditions were brutal.

Constant combat, inadequate supplies, surrounded by a hostile population.

Letters from August’s commanding officer, preserved in military archives, painted a grim picture.

The men of Struff Baton 9999 are given the most dangerous assignments.

They clear minefields, conduct forward reconnaissance under enemy fire, and are the first in every engagement.

Casualties are extremely high.

The last confirmed sighting of August came from a fellow soldier in the penal battalion recorded in a postwar testimony.

I saw August in October 1944 near the village of Havar.

We were under heavy partisan attack.

August was in the forward position.

There was an explosion, artillery or a mine, I couldn’t tell.

When the smoke cleared, several men were gone.

August was one of them.

We never found his body.

August was officially declared missing in action in October 1944.

He was 34 years old.

He never saw his daughters again after they were taken from him in 1940.

He never knew that Irma had been murdered 2 years earlier.

David sat at his desk staring at the photograph that had started this entire investigation.

The man with crossed arms standing defiant among a sea of raised salutes had lost everything.

His love, his children, his freedom, and finally his life.

He never surrendered,” David said quietly to Rebecca.

“Even at the end, forced into a penal battalion, sent to die in a foreign land, he never surrendered who he was.

” But the story wasn’t over.

Somewhere, Ingred and Irene had survived, and they deserved to know what their father had sacrificed for them.

Finding Ingred and Irene proved to be the most emotionally complex part of the investigation.

After the war, thousands of children had been displaced, orphaned, or separated from their families.

Tracking two specific girls through that chaos required patience, luck, and connections across multiple institutions.

Rebecca made the breakthrough.

Working with the International Tracing Service in Bad Arson, Germany, an archive dedicated to documenting victims of Nazi persecution.

She found records showing that Ingred and Irene had been transferred from the Hamburgg orphanage to different foster families in 1943.

They were separated, Rebecca told David over the phone, her voice heavy.

The Nazis decided to place them with different families, probably to make them easier to assimilate, to erase their Jewish heritage and their connection to each other.

Ingred, the older daughter born in 1935, was placed with a family in rural Bavaria.

Irene, born in 1937, was sent to a family in Lower Saxony.

Neither family told the girls the truth about their parents.

Both were given new identities and told their parents had died.

Postwar records showed that Ingred grew up never knowing her real surname.

She was told she was an orphan of the war.

nothing more.

She married in 1954, had children, lived an ordinary life in Munich.

She never knew her father was the man in the famous photograph.

She never knew her mother had been murdered.

She never knew she had a sister.

Irene’s story was similar.

She grew up believing she was the biological daughter of her foster parents.

She became a teacher, married, settled in Bremen.

Like Ingred, she lived her entire adult life without knowing the truth.

They lived 50 years without knowing who they really were, David said, overwhelmed by the tragedy of it.

Their father died trying to protect them.

their mother was murdered and they never knew.

But in the late 1980s, something began to change.

Germany was starting to confront its past more honestly.

Archives were opening.

Researchers were investigating.

The Berlin Wall fell in 1989, and suddenly documents from East Germany became accessible.

Klaus discovered that in 1990, a German researcher named Professor Wulfr was investigating Nazi era labor camp records and came across August’s name.

Following the paper trail, Sailik found the orphanage records showing Ingred and Irene’s placement.

Sick made it his mission to find the daughters and tell them their true history.

After months of searching, he located Irene and Bremen.

In 1991, the same year David had found the photograph, Sale contacted her.

David obtained a copy of Saleik’s notes from that first meeting.

Irene was 54 years old when she learned the truth.

She had lived her entire life as someone else.

Now, suddenly she discovered she had a Jewish mother who had been murdered, a father who had defied the Nazis and died in a penal battalion, and a sister she never knew existed.

She was devastated, Klaus told David, but also angry.

Angry that she had been lied to for 50 years.

Angry that her parents had been taken from her, angry that no one had tried to tell her the truth.

Sailing helped Irene locate Ingred.

The two sisters met for the first time since they were separated as children.

They were strangers to each other, yet connected by blood, by loss, by a history.

They were only now beginning to understand.

Ingred was more reserved, Klaus explained.

She had built a life based on one identity.

Learning she was someone else entirely was almost too much to process.

But both sisters wanted to know more.

They wanted to understand what had happened to their parents, why they had been separated, why their father had defied the Nazis.

And then David found the photograph.

David knew he had to contact the daughters.

This wasn’t just a historical investigation anymore.

This was about two women who deserved to know who their father had been, what he had stood for, and why his courage mattered.

Through Klaus and Professor Seig, David arranged a meeting with Irene and Breman in the spring of 1992.

He brought copies of all his research, documentation of August and Irma’s relationship, the arrest records, the camp assignments, and most importantly, the photograph from the shipyard.

Irene was a dignified woman in her mid-50s with gray streaked hair in her father’s determined jawline.

She greeted David with cautious politeness in her comfortable apartment overlooking the VZA River.

Professor Sig told me you found something about my father, she said in careful English.

I want to know everything.

David spread the documents across her dining table, walking her through the timeline.

He showed her the police files documenting August’s relationship with Irma, the marriage application that was denied, the arrest records, the concentration camp assignment, the military records from Croatia.

Irene listened in silence, occasionally asking questions, her hands folded tightly in her lap.

When David finally pulled out the photograph from the shipyard, she gasped.

“That’s him,” she whispered, staring at the man with crossed arms.

“That’s August Land Messer, your father.

” Irene took the photograph with trembling hands, holding it close, studying every detail of her father’s face.

A face she had no memory of yet, which looked somehow familiar in ways she couldn’t articulate.

“Everyone else is sluting,” she said quietly.

“But he’s not.

” Why? Because by June 1936, he had already chosen love over conformity.

David explained.

He had already been expelled from the Nazi party for refusing to leave your mother.

He was standing there surrounded by hundreds of people giving the Hitler salute and he refused.

He crossed his arms and refused.

Tears ran down Irene’s face.

He lost everything.

She said, “My mother, me, Ingred, everything.

And still he didn’t surrender.

” “No,” David agreed.

“He never surrendered.

” Over the next hours, David and Irene went through every document, every piece of evidence, every fragment of August and Irma’s story.

She learned about her mother’s deportation and murder, about her father’s final years in the penal battalion, about the desperate attempts they had made to flee Germany together, to keep their family intact against impossible odds.

I need to show this to Ingred, Irene finally said.

She needs to know.

Well, two weeks later, David met both sisters in Hamburgg in the same city where their father had once worked, where he had fallen in love with their mother, where he had stood in defiance at a shipyard ceremony 56 years earlier.

Ingred was quieter than Irene, more reserved.

But the emotion in her eyes when she saw the photograph was unmistakable.

“All my life, I felt like I didn’t belong anywhere,” Ingred said softly.

“Now I know why.

I came from love that was illegal.

I came from parents who chose each other over everything else.

I came from courage.

The three of them stood together looking at the photograph that had revealed so much.

The man with crossed arms was no longer anonymous.

He was August.

He was a father.

He was someone who had loved deeply enough to defy an entire regime.

Thank you, Irene said to David.

Thank you for finding him.

Thank you for making sure he’s remembered.

But David knew the story couldn’t end there.

The world needed to know about August Lan Messer.

His courage deserved recognition.

After meeting Irene and Ingred, David returned to New York, determined to share August’s story with the world.

This wasn’t just a footnote in history.

This was a powerful testament to individual resistance, to the courage required to choose love and dignity over conformity and hate.

He wrote an article for the Journal of Modern History detailing the discovery of the photograph and the investigation that followed.

He included interviews with Irene, testimony from witnesses who had known August, and analysis of why this image mattered.

The article was published in the fall of 1992 and the response was immediate and overwhelming.

Newspapers across America picked up the story.

The New York Times ran a front page feature.

Time magazine published the photograph with the headline, “The man who said no, discovering August Lan Messer.

” Television networks wanted interviews.

Documentary filmmakers wanted to tell the story, but David insisted that the focus remain on August and his family, not on the American professor who had found the photograph.

“This isn’t my story,” David told reporters.

It’s the story of a man who loved a woman they told him he couldn’t love and who refused to hate when the world demanded it.

That’s what people need to understand.

The photograph itself became iconic.

It was displayed at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington with a placard explaining August’s story.

It was featured in history textbooks, in exhibitions about resistance to Nazism, and documentaries about the Holocaust.

Schools across America began teaching about August Land Messer.

Students studied the photograph, discussed what courage means, debated whether they would have the strength to stand alone in a crowd of conformity.

Irene and Ingred, initially hesitant about public attention, gradually came to appreciate the power of their father’s legacy.

Irene especially became an advocate for remembering individual resistance.

People always ask, “What would I have done?” Irene said during a speech at the Holocaust Museum in 1994.

My father answered that question.

He was an ordinary man, a worker, not a politician or a philosopher.

But when the moment came to choose between conformity and conscience, he chose conscience.

That choice cost him everything.

But it also meant his children could grow up knowing their father was a man of integrity.

The story resonated particularly strongly in America, where discussions about civil rights, conformity, and individual resistance had their own complicated history.

August became a symbol that transcended his specific historical moment, a reminder that ordinary people in any time and place might be called to make extraordinary choices.

Academic conferences analyzed the photograph.

Psychology professors used it to teach about conformity and group dynamics.

Ethics classes debated the moral obligations individuals have to resist unjust systems.

But for David, the most meaningful response came from ordinary people.

He received hundreds of letters from across America from students, teachers, veterans, immigrants, people who saw in August’s crossed arms a reflection of their own struggles to maintain dignity in difficult circumstances.

One letter from a black woman in Birmingham, Alabama, particularly moved him.

My grandfather participated in the bus boycott in the 1950s.

He lost his job, faced threats, was arrested multiple times.

When I saw August Land Messer’s photograph, I saw my grandfather.

The contexts were different, but the courage was the same.

Thank you for showing the world that resistance is possible even when it seems impossible.

August Lanesser’s story had transcended history and become something universal.

A testament to the power of individual conscience in the face of collective madness.

25 years after David first discovered the photograph in 2016, Irene stood at the Blumvos shipyard in Hamburg.

The place where her father had once worked, where he had stood with arms crossed in defiant resistance, had changed dramatically.

The massive cranes and industrial buildings remained, but the world around them had transformed.

She was 79 years old now, a grandmother, her life rich with family and experiences her parents never got to witness.

Ingred had passed away 2 years earlier, but her children had come to the ceremony, wanting to honor the grandfather they never met.

The city of Hamburg had decided to create a memorial, not a grand monument, but something more intimate and powerful.

A bronze plaque installed in the pavement at the exact spot where August had stood on June 13th, 1936.

Irene read the inscription aloud, her voice steady despite the emotion.

August Lan Messer, 1910 1944.

He stood here and refused.

His courage reminds us that individual resistance is always possible, even in the darkest moments of history.

Around her stood her children and grandchildren, representatives from the city government, students from local schools, and survivors of Nazi persecution from across Germany.

David had flown in from New York, now retired, but still passionate about August’s story.

“My father was not a hero who set out to change the world,” Irene said to the assembled crowd.

“He was a man who fell in love.

” “When the world told him that love was illegal, that it was shameful, that it was wrong.

He refused to listen.

He chose love.

He chose his family.

He chose to remain human when the world demanded he become a monster.

” She paused, looking at the photograph that had been enlarged and displayed on a nearby wall.

The same image David had found 25 years earlier.

the man with crossed arms standing alone in a sea of conformity.

For 50 years, I didn’t know who my father was.

I didn’t know my mother.

I didn’t know my sister.

The Nazis took everything from us.

Our parents, our identity, our history.

But they couldn’t take away what my father stood for.

They couldn’t erase his refusal.

That photograph survived.

The truth survived.

And now, finally, his courage is recognized.

A young German student, no more than 16, raised her hand tentatively.

What do you want people to learn from your father’s story? She asked.

Irene smiled gently.

I want them to learn that ordinary people can do extraordinary things.

My father wasn’t a politician or a military officer.

He was a shipyard worker.

But when the moment came to choose between safety and conscience, he chose conscience.

And I want people to know that those choices are never easy.

My father paid a terrible price.

My mother paid a terrible price.

But they never surrendered who they were.

She looked at her grandchildren, seeing in their faces the continuation of August and Irma’s legacy.

A legacy that the Nazis had tried to destroy, but which had, against all odds, survived.

Every generation faces moments when they must choose between conformity and resistance, between complicity and courage.

My father’s photograph reminds us that individuals matter.

One person standing with arms crossed in a crowd of thousands.

It seems so small, so insignificant.

But that gesture rippled across time.

It inspired people I never met in countries my father never knew existed.

His refusal became a symbol of hope.

David approached the memorial, laying a white rose on the plaque.

August Lantresser showed us that love is resistance, he said quietly.

In a world built on hate, choosing to love someone they told you to hate is revolutionary.

In a system demanding conformity, maintaining your humanity is defiance.

The ceremony concluded, but people lingered, staring at the photograph, reading the plaque, taking pictures to share with friends and family around the world.

August’s story would continue to spread, continue to inspire, continue to challenge people to ask themselves, “What would I do? Would I have the courage to stand alone?” As Aren walked away from the shipyard, her grandchildren beside her, she felt something she hadn’t expected.

Peace.

For 79 years, she had lived with questions about her parents, with gaps in her identity, with the trauma of having been separated from everything she should have known.

Now, finally, she understood.

Her father was August Lan Messer, the man who said no.

Her mother was Irma Eckler, the woman who loved him despite the world’s hatred.

And she, Irene, was the living continuation of their courage, their love, their refusal to surrender.

The photograph would remain a frozen moment in 1936, a man standing alone with arms crossed.

But its meaning would continue to grow, reaching across decades and continents, reminding every generation that resistance begins with a single person choosing conscience over conformity, love over hate, dignity over fear.

August Lan Messer never knew his defiant stance would be photographed.

He never knew that image would survive.

He never knew that 70 years later his daughters would learn his story and the world would celebrate his courage.

But he knew in that moment in 1936, standing in the Hamburg shipyard with his arms crossed while hundreds around him raised their arms in salute, that he could not surrender who he was.

And that knowledge, that choice, that single gesture of refusal became his legacy and his gift to all who would come

News

🚛 HIGHWAY CHAOS — TRUCKERS’ REVOLT PARALYZES EVERY LAND ROUTE, KHAMENEI SCRAMBLES TO CONTAIN THE FURY 🌪️ The narrator’s voice drops to a biting whisper as convoys snake through empty highways, fuel depots go silent, and leaders in Tehran realize this isn’t just a protest — it’s a nationwide blockade that could topple power and ignite panic across the region 👇

The Reckoning of the Highways: A Nation on the Edge In the heart of Tehran, the air was thick with…

🎬 MEL GIBSON DROPS THE BOMBSHELL — “THE RESURRECTION” CAST REVEALED IN A MIDNIGHT MEETING THAT LEFT HOLLYWOOD GASPING 😱 The narrator hisses with delicious suspense as studio doors slam shut, contracts slide across tables, and familiar faces emerge from the shadows, each name more explosive than the last, turning what should’ve been a simple casting call into a cloak-and-dagger spectacle worthy of a conspiracy thriller 👇

The Darkened City: A Night of Reckoning In the heart of Moscow, a city that once stood proud and unyielding,…

🎬 MEL GIBSON DROPS THE BOMBSHELL — “THE RESURRECTION” CAST REVEALED IN A MIDNIGHT MEETING THAT LEFT HOLLYWOOD GASPING 😱 The narrator hisses with delicious suspense as studio doors slam shut, contracts slide across tables, and familiar faces emerge from the shadows, each name more explosive than the last, turning what should’ve been a simple casting call into a cloak-and-dagger spectacle worthy of a conspiracy thriller 👇

The Shocking Resurrection: A Hollywood Revelation In a world where faith intertwines with fame, the announcement sent ripples through the…

🎬 “TO THIS DAY, NO ONE CAN EXPLAIN IT” — JIM CAVIEZEL BREAKS YEARS OF SILENCE ABOUT THE MYSTERY THAT HAUNTED HIM AFTER FILMING ⚡ In a hushed, almost trembling confession, the actor leans back and stares past the lights, hinting at strange accidents, eerie coincidences, and moments on set that felt less like cinema and more like something watching from the shadows, leaving even hardened crew members shaken to their core 👇

The Unseen Shadows: Jim Caviezel’s Revelation In the dim light of a secluded room, Jim Caviezel sat across from the…

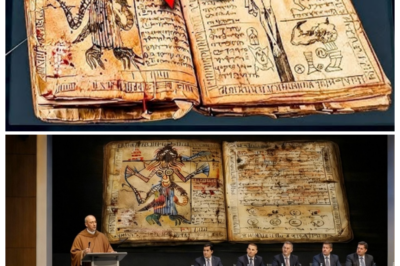

📜 SEALED FOR CENTURIES — ETHIOPIAN MONKS FINALLY RELEASE A TRANSLATED RESURRECTION PASSAGE, AND SCHOLARS SAY “NOTHING WILL BE THE SAME” ⛪ The narrator’s voice drops to a breathless whisper as ancient parchment cracks open under candlelight, hooded figures guard the doors, and words once locked inside stone monasteries spill out, threatening to shake faith, history, and everything believers thought they understood 👇

The Unveiling of Truth: A Resurrection of Belief In the heart of Ethiopia, where the ancient echoes of faith intertwine…

🕯️ FINAL CONFESSION — BEFORE HE DIES, MEL GIBSON CLAIMS TO REVEAL JESUS’ “MISSING WORDS,” AND BELIEVERS ARE STUNNED INTO SILENCE 📜 The narrator’s voice drops to a hushed, dramatic whisper as old notebooks open, candlelight flickers across ancient pages, and Gibson hints that lines never recorded in scripture could rewrite everything the faithful thought they knew 👇

The Unveiling of Hidden Truths In the dim light of his private study, Mel Gibson sat surrounded by piles of…

End of content

No more pages to load