From Gamble to Groom: The Plantation Owner Forced to Wed His Fat Enslaved Housemaid (1852)

Welcome to one of the most disturbing cases ever recorded in American history.

Before we begin, I invite you to leave in the comments where you’re watching from and the exact time you’re listening to this narration.

We’re interested to know what places and what times of day or night these documented accounts reach.

In the autumn of 1852, a series of unusual events began to unfold at Raven’s Cross Plantation in Bouford County, South Carolina.

The events would forever alter the lives of those involved and leave an indelible mark on the region’s history.

The once prestigious Harrington family name became associated with whispers and averted gazes when mentioned in polite society.

According to county records, on November 13th, 1852, plantation owner Elias Harrington, aged 31, filed unusual documentation with the local magistrate.

What made these papers remarkable was not their existence, but rather what they omitted.

The spaces where a bride’s name should have appeared, were conspicuously blank, though witnesses had signed their names attesting to a legal union.

Local newspaper archives from the Charleston Mercury, dated November 15th, briefly mentioned that a wedding of unusual circumstance has occurred at Raven’s Cross without providing further details.

This vague reference marked the beginning of what investigators in 1939 would later call the silence of Raven’s Cross.

The plantation situated approximately 17 mi from Charleston proper had long been known for its rice production and the Harrington family’s particular brand of detached cruelty toward those they enslaved.

Elias Harrington had inherited the property following his father’s death in 1847 and by all accounts was regarded as a calculating businessman with a fondness for gambling that bordered on obsession.

The Bowford County Historical Society archives contain fragmentaryary accounts indicating that in the months preceding November 1852, Harrington had accumulated substantial debts to a merchant banker from Philadelphia named Isaac Thornton.

Correspondence between the men discovered during the renovation of the Charleston Customs House in 1963 revealed a series of increasingly desperate pleas from Harrington for extensions on his payment deadlines.

The final letter in this collection dated October 28th, 1852 contains only the cryptic line, “The matter is resolved as discussed.

You shall have your satisfaction, though not in the manner originally intended.

What happened in the intervening weeks, remains subject to speculation and the scattered accounts of household staff that were later recorded by Harriet Jacobs, a writer who documented slave narratives in the 1860s.

According to these accounts, Thornton arrived at Raven’s Cross on November 10th with documents that would have transferred ownership of the plantation had Harrington not agreed to certain terms.

The nature of these terms was not explicitly stated in any surviving records, but the household staff reported that Thornton departed the following morning, looking uncommonly pleased with himself, while Harrington remained locked in his study for 2 days, refusing meals and visitors.

The overseers log from this period preserved in the South Carolina historical archive notes unusual instructions to prepare the small chapel on the grounds for a ceremony and to ensure that a woman identified only as M was bathed, dressed appropriately, and brought to the main house on the evening of November 12th.

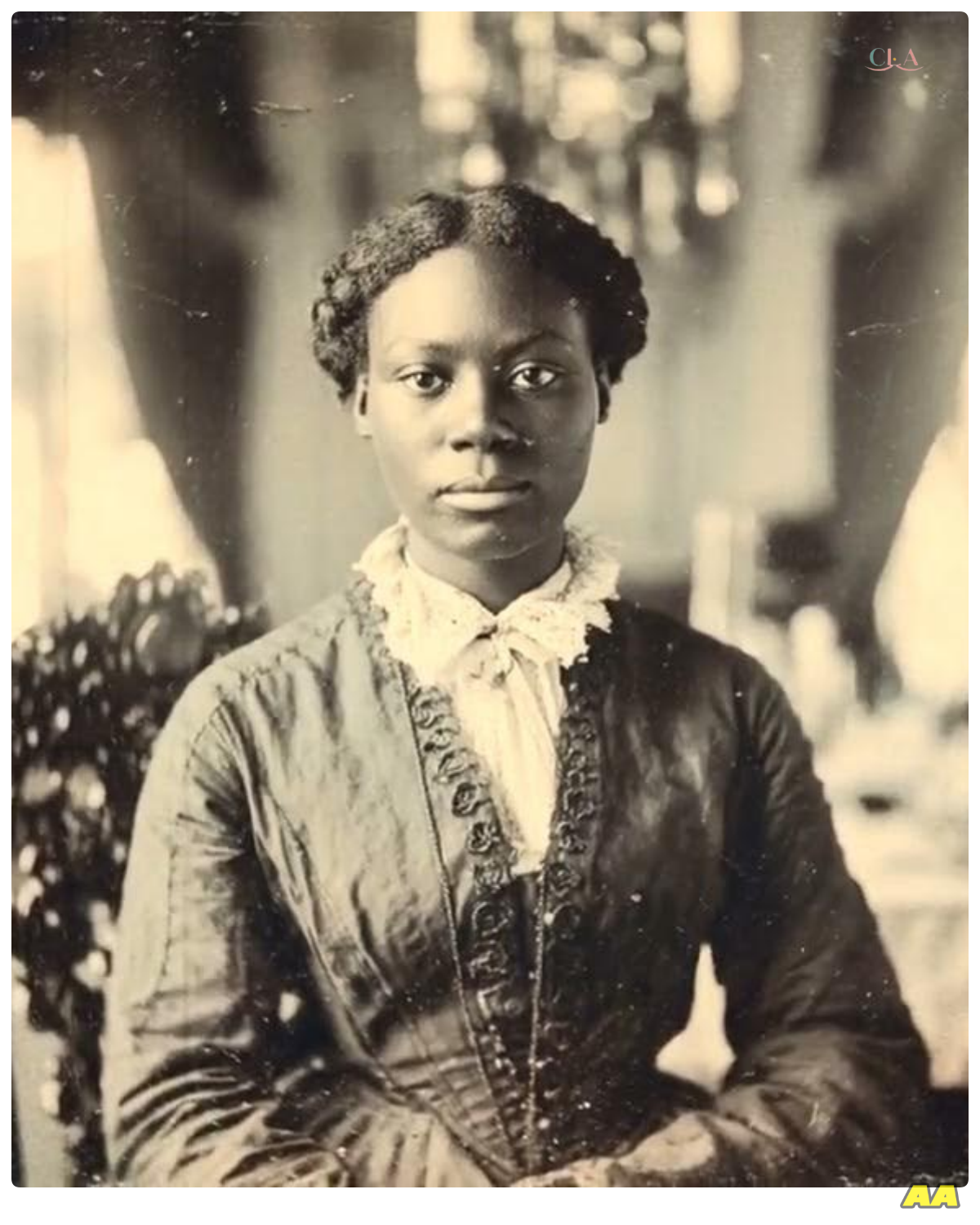

The identity of this woman remained unrecorded in official documentation, but household accounts consistently refer to a Martha described as an enslaved woman who worked primarily in the plantation house kitchen.

Martha was reportedly in her late 20s and according to the household inventory from 1850 was valued at $800, a sum lower than most domestic workers, with a notation indicating she was stout in figure unsuitable for field labor.

The morning after the mysterious ceremony, several notable changes occurred at Raven’s Cross.

The overseer’s log indicates that Martha was removed from kitchen duties and assigned a small room adjacent to the main house that had previously served as a sewing room.

Additionally, Harrington instructed that she was to be addressed as madam by the household staff, an instruction that was enforced with unusual severity.

According to accounts collected by Jacobs, one young enslaved man who failed to use this title was sold to a plantation in Georgia the following day.

What makes this case particularly disturbing is not merely the implied nature of the arrangement, but the psychological transformation that witnesses described in both Harrington and Martha in the months that followed.

Harrington, once known for his sociable nature among Charleston’s elite families, withdrew from society.

The plantation’s guest ledger, which had regularly recorded weekend hunting parties and evening entertainments, shows only three visitors between November 1852 and June 1853, all of them business associates rather than social callers.

Martha’s transformation was reportedly more complex.

According to kitchen staff accounts, she initially appeared terrified and confused by her change in status.

One account describes her hands shaking so severely during her first dinner at the main house that she shattered a porcelain cup, resulting in her confinement to her room for 3 days.

By February 1853, however, household staff reported that Martha had adopted an unnervingly calm demeanor.

She rarely spoke, even when addressed directly, but was observed watching Harrington with an intensity that made the household staff uncomfortable.

The plantation’s expense ledgers from this period show unusual purchases.

A set of women’s clothing from a dress maker in Charleston who typically served the elite families of the region, a silver hand mirror, and most curiously, a locked wooden box with brass fittings delivered from a cabinet maker in Savannah.

The purpose of this box remained unknown until 1896 when the plantation house underwent renovation following a minor fire and the box was discovered sealed inside a wall cavity in what had been Martha’s room.

The contents of the box, according to the account of Reverend Thomas Witmore, who was present when it was opened, included several unusual items.

A contract written in what appeared to be blood rather than ink.

a small cloth doll with pins inserted into its torso and a letter addressed to my dearest daughter dated 1831.

This letter now preserved in the University of South Carolina’s special collections was written by a woman who identified herself only as your mother who loves you still though we are parted.

The letter suggests that Martha may have been the daughter of her owner, a not uncommon circumstance on plantations, but rarely acknowledged so explicitly in writing.

By June 1853, the situation at Raven’s Cross had deteriorated further.

The plantation’s financial records show declining productivity and correspondence between Harrington and his cotton factor in Charleston indicates increasing concern about the plantation’s viability.

More troubling are the medical records kept by Dr.

William Fincher, who attended to the plantation’s enslaved population.

his ledger notes treating Harrington for nervous exhaustion and persistent insomnia on four occasions between March and June.

The doctor’s private notes discovered among his effects after his death in 1878 express concern about Harrington’s mental state, describing him as a man consumed by some private terror he refuses to name.

On July 7th, 1853, Harrington was found dead in his study.

The official cause of death was recorded as apoplelexi, a common diagnosis for sudden death at the time.

However, doctor Fincher’s private correspondence with a medical colleague in Philadelphia uncovered during research for a medical history of the region in 1957, suggests he suspected poisoning, but had no means to prove it.

The letter states, “The circumstances are such that I dare not suggest my suspicions openly, but the dilation of the pupils and the unusual rigidity of the corpse are consistent with certain plant toxins known to be used in folk remedies by some of the African population.

What happened to Martha following Harrington’s death remains one of the most disturbing aspects of this case.

According to plantation records, she was not present among the enslaved persons inventoried for the estate settlement.

No record of her sale exists, nor any documentation of manumission.

She simply vanished from all official records.

Local folklore collected by WPA writers in the 1930s includes stories of a woman matching Martha’s description who appeared in a small maroon community in the swamplands near the Comhe River.

approximately 30 mi from Raven’s Cross.

These accounts describe her as refusing to speak of her past, but possessing unusual items of value, including silver table wear and a man’s gold pocket watch.

The most compelling evidence for what may have actually occurred at Raven’s Cross came to light in 1959 when archaeologists from the University of North Carolina conducted an examination of the plantation cemetery.

Among the marked graves of the Harrington family, they discovered an unmarked burial approximately 6 ft from Elias Harrington’s headstone.

The skeletal remains were those of a woman estimated to have been in her late 20s or early 30s at time of death.

What made this discovery particularly strange was the presence of expensive jewelry buried with the body, items consistent with those that would have belonged to the lady of the plantation, and the position of the skeleton’s hands, which were bound together with what appeared to be silk ribbon that had partially survived decomposition.

The investigation was never completed.

According to newspaper accounts from the Colombia State dated August 12th, 1959, the lead archaeologist, Dr.

James Merritt, abruptly abandoned the project after allegedly experiencing what colleagues described as a severe psychological break.

He resigned his position at the university and reportedly moved to Arizona, refusing all further contact with former associates.

His field notes preserved in the university archives end with a disturbing entry.

Something is wrong with this place.

I dreamed of her again last night.

She was standing at the foot of my bed, watching, not speaking, just watching.

The weight of her gaze was unbearable.

In 1961, Reverend Whitmore’s grandson donated a collection of his grandfather’s papers to the Charleston Historical Society.

Among them was a journal containing an account of a conversation with an elderly woman named Pearly May Johnson in 1910.

Johnson had been a child at Raven’s Cross during the events of 1852 and 1853.

Her account offers perhaps the most disturbing perspective on what transpired.

According to Reverend Whitmore’s notes, Johnson claimed that Martha had indeed married Harrington under duress as part of some arrangement with Thornton, but what followed was not what either man had anticipated.

Johnson described Martha as having knowledge of root work, traditional African spiritual practices that had been preserved among some of the enslaved population.

In the weeks following the marriage, Johnson claimed to have witnessed Martha collecting specific plants from the plantation grounds at night and adding substances to Harrington’s food.

She described Harrington as changing gradually, becoming increasingly compliant to Martha’s quietly spoken suggestions.

Johnson’s account suggests that by April 1853, it was Martha, not Harrington, who was effectively making decisions regarding the plantation’s operations, though these decisions were still voiced by Harrington himself.

Most disturbing was Johnson’s description of Martha’s demeanor during this period.

According to Witmore’s notes, Johnson said, “She never raised her voice, never showed anger.

She would sit for hours just watching him.

Sometimes she would smile, but never with her eyes.

Her eyes stayed cold.

Cold like riverstones in winter, and he knew.

Toward the end, he knew what was happening to him.

But he couldn’t stop it.

Couldn’t stop himself from doing whatever she whispered to him to do.

The archaeological survey of 1959 also revealed another troubling detail that was only briefly mentioned in the official report before the project was abandoned.

In the basement of the plantation house beneath the floorboards of what had been Martha’s room, they discovered a small cavity containing a collection of personal items.

a man’s crevat pin, a lock of hair tied with string, and most significantly, pages apparently torn from Harrington’s personal journal.

These pages, now housed in the South Carolina Historical Society archives, contain increasingly frantic entries from May and June 1853.

One entry reads, “I can no longer trust my own mind.

My thoughts seem foreign to me as though someone else places them there.

I find myself doing things I have no memory of deciding to do.

The servants look at me with fear, but not the kind of fear I once inspired.

It is as though they see something in me that I cannot see myself.

The final entry, dated June 29th, just days before Harrington’s death, contains only a single line.

She watches me even when she is not in the room.

I can feel her gaze penetrating the walls.

What actually occurred at Raven’s Cross Plantation during those 8 months remains subject to speculation.

The official record states simply that Elias Harrington died of natural causes and that the plantation was sold to pay his outstanding debts.

No mention is made of a wife or widow in any of the probate documents.

The plantation itself changed hands several times in the decades that followed before being largely abandoned after the Civil War.

The main house remained standing until 1942 when it was destroyed by fire under circumstances that the local sheriff’s report described as suspicious in nature but lacking evidence of specific wrongdoing.

Today, only the foundations of Raven’s Cross remain visible, partially reclaimed by the surrounding forest.

The site is located on private property and is not accessible to the public.

According to local residents interviewed in 1968 for an oral history project conducted by Emory University, the area has a reputation for being unwelcoming.

One elderly resident who declined to be identified claimed that on certain nights, particularly in November, it is possible to see lights moving among the ruins, though no one has lived there for generations.

The case of Elias Harrington and the woman known only as Martha represents a disturbing chapter in American history, not merely for the implied circumstances of their union, but for the psychological warfare that appears to have followed.

It stands as a stark reminder of how systems of oppression can create the conditions for profound psychological horror and how the dynamics of power can shift in unexpected and disturbing ways.

Her notes, which were never published, but are preserved in the university archives, contain a passage that perhaps best summarizes the lingering unease that surrounds this case.

What happened at Raven’s Cross was not merely a reversal of power, but something more fundamentally disturbing, a demonstration that bondage takes many forms, and that the human capacity for patient, calculating vengeance can transcend even the most oppressive circumstances.

the Charleston County property.

Records indicate that the land where Ravens Cross once stood was purchased in 1968 by a corporation registered in Delaware.

In 1967, a graduate student in history at Howard University attempted to research the case further, but abandoned her dissertation after reportedly experiencing nightmares so severe that she required hospitalization.

All attempts by historical researchers to access the property since then have been denied.

The last known photograph of the ruins taken from the adjacent public road in 1970 shows only crumbling stone foundations and a single chimney standing amid encroaching vegetation.

The photographer, amateur historian Robert Mercer, noted in his journal that while developing the film, he noticed what appeared to be a figure standing among the ruins, a figure not visible when he had taken the photograph.

Mercer never returned to the site.

Some historians have suggested that the story of Raven’s Cross represents nothing more than a cautionary tale about the moral corruption inherent in the institution of slavery.

Others point to the unusual consistency in accounts from various sources spanning more than a century as evidence that something truly disturbing occurred there.

Something that cannot be easily dismissed or explained away.

Whatever the truth may be, the silence that descended over Raven’s Cross in November 1852 continues to echo through the historical record.

A reminder that some chapters of history resist full illumination, perhaps because what they might reveal about human nature is too disturbing to confront directly.

In 1957, a descendant of Isaac Thornton donated a collection of family papers to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Among them was a single page of correspondence dated October 3rd, 1852.

Apparently written by Thornton to a business associate in New York.

The letter contains a passage that adds yet another disturbing dimension to the case.

I have devised a most amusing solution to the Harrington debt.

The man’s pride will be his undoing.

He believes himself to be purchasing time with this arrangement.

But I am purchasing something far more valuable, the opportunity to witness justice of a poetic nature.

The woman remembers him, though he does not remember her.

She has waited a very long time for this reunion.

The implication that Thornton and Martha may have been collaborating in some way, and that Martha and Harrington had some prior connection unknown to him, has never been definitively proven.

The trail of evidence grows cold here, lost to time, and the deliberate destruction of records that might have provided clarity.

What remains is a haunting sense that at Raven’s Cross plantation, a complex and terrible form of justice may have been enacted through means that rational history struggles to accommodate.

The land where Raven’s Cross once stood remains undeveloped to this day.

Local residents still avoid the area after dark.

Some claim to hear sounds coming from the property on certain nights.

Not screams or wailing as ghost stories might suggest, but something perhaps more unsettling.

The sound of quiet, patient footsteps moving back and forth, back and forth, as though someone is still waiting, still watching, still not quite finished with whatever began there in the autumn of 1852.

In 1969, the last known direct descendant of Elias Harrington died in a nursing home in Virginia.

According to the attending physician’s notes, his final coherent words were, “She’s still waiting for me.

She’s been waiting all this time.

” When asked who he meant, the elderly man reportedly became agitated and would only say, “The one who watches, the one who waits, the one who knows.

” He died later that evening.

The nursing home staff reported that despite the room being kept at a comfortable temperature, his body was found unusually cold to the touch.

Perhaps the most fitting epitap for this disturbing chapter in American history comes from the fragmentaryary journal of Martha herself, three pages of which were discovered inside the lining of a dress preserved in the textile collection of the Charleston Museum in 1964.

The final entry dated July 6th, 1853, the day before Harrington’s death, reads simply, “Tomorrow I will be free.

” Not as he understands freedom, but as I have come to understand it.

Freedom is not merely the absence of chains, but the presence of justice, and justice, like vengeance, is a dish best served with patience.

I have waited 7 years for tomorrow.

I could have waited 70 if necessary.

Some hungers transcend time.

The case of Raven’s Cross remains officially unsolved, though perhaps unresolved would be a more accurate term.

What transpired there continues to resist conventional historical analysis, remaining instead in that shadowy territory where documented fact meets psychological horror.

A reminder that the darkest chapters in human history are not always those written in blood, but sometimes those written in the invisible ink of calculated silence and patient retribution.

In 2002, during an academic conference on historic preservation in Charleston, Professor Amelia Richardson from Georgetown University presented findings from her research into Raven’s Cross.

Among her discoveries was a series of letters between Isaac Thornton and his sister in Boston dated between 1845 and 1852.

These letters found in a private collection and never before made public revealed a connection that cast the entire case in an even more disturbing light.

According to Thornton’s correspondence, Martha had once been owned by the Harrington family when Elias’s father was still alive.

She had been sold to Thornton’s business associate in Philadelphia in 1845 following an incident described only vaguely as a matter requiring distance and discretion.

Thornton wrote that Martha had been instrumental in certain business arrangements and that he had found her insights into the Harrington household invaluable.

Most significantly, a letter dated September 1852 contained a passage that suggested Martha had specifically requested to be returned to Raven’s Cross.

The woman insists that the time has come for her return.

She speaks of it with such certainty that I find myself convinced of her purpose, though she reveals little of what that purpose might be.

She has served me well these seven years, and if this final service to her results in the resolution of the Harrington debt, I consider it an arrangement beneficial to all parties, save perhaps Harrington himself, though his suffering is of no consequence to me.

Professor Richardson’s research also uncovered census records from 1840 that listed a female child aged approximately four years among the Harrington plantation’s enslaved population.

The child was recorded as Martha Mulatto with a notation indicating she was daughter of kitchen woman Esther.

Subsequent census records from 1850 showed no listing for an enslaved woman named Esther at Raven’s Cross.

Parish death records from St.

Michael’s Church in Charleston, dated May 1844, include an entry for burial of enslaved woman Esther, property of Harrington Plantation, aged approximately 28 years, cause of death, falling from height.

The brevity and clinical nature of this entry belies what local oral histories collected by Richardson from descendants of formerly enslaved families in the region suggest was a far more troubling incident.

According to these accounts passed down through generations, Esther had not fallen, but had been pushed from an upper window of the plantation house following an altercation with Harrington Senior.

The nature of this altercation was never explicitly stated, but several accounts implied that Esther had threatened to reveal something that would have damaged the Harrington family’s reputation, possibly related to the parentage of her daughter.

This historical context added a new dimension to Martha’s actions years later.

What had appeared to be a simple case of role reversal and psychological manipulation now suggested something more calculating, a yearslong plan for a very specific form of justice.

If Martha was indeed the daughter of Elias Harrington’s father, as the circumstantial evidence suggested, then her engineered marriage to Elias carried disturbing implications of calculated retribution across generations.

Dr.

Lawrence Peton, a historian specializing in the psychological aspects of American slavery, wrote in his 2005 analysis of the case, “What makes Raven’s Cross uniquely disturbing is not merely the inversion of power, but the methodical patience with which this retribution was apparently planned and executed.

If the available evidence is to be believed, Martha waited seven years for her opportunity, cultivated the necessary alliance with Thornton, and then implemented a psychological campaign that systematically dismantled not just Harrington’s status and sanity, but his very sense of self.

This represents a form of psychological warfare that is both horrifying and in the context of the profound injustices of slavery uncomfortably understandable.

In 1948, a collection of folk remedies and practices was documented by ethnographer Rebecca Mitchell among elderly formerly enslaved people living in coastal South Carolina.

One section titled ways of binding described methods by which one person could allegedly gain psychological control over another through a combination of herbal preparations and psychological manipulation.

The text noted, “The most powerful binding is achieved not through force or fear, but through patience and the gradual replacement of the target’s will with one’s own.

” The process is described as hollowing out the person from within, creating a shell that moves and speaks as directed while believing itself to still be autonomous.

This folk practice bears striking similarities to the transformation described in Harrington during the months before his death.

Whether such methods could actually produce the effects attributed to them remains a matter of scientific skepticism.

But the psychological aspects, the creation of dependency, the erosion of will through isolation and manipulation are well doumented phenomena in modern psychological literature.

Perhaps the most tangible evidence regarding Martha’s fate came to light in 1962 when a small leatherbound journal was discovered during the renovation of a historic home in St.

Augustine, Florida.

The journal which covered the period from August 1853 to March 1854 was written by a woman who identified herself only as MH.

The contents described a journey southward from South Carolina and the establishment of a new life under an assumed identity.

The journal made no direct reference to Raven’s Cross or Harrington, but contained several passages that seemed to allude to a previous life and a concluded act of retribution.

One entry dated December 21st, 1853 read, “I dreamed of the plantation last night.

In my dream, I stood in his study once more, watching as he wrote the letters I dictated.

His hand moved across the page, but the words were mine.

Even in death, he serves my purpose.

The papers transferring ownership are legally binding, though the name I used is not my own.

The transaction is complete.

The circle is closed.

What was taken has been returned.

Handwriting analysis conducted by the University of Florida in 1965 concluded with high probability that the journal author was the same person who had written the three pages found in the dress lining at the Charleston Museum.

If this was indeed Martha’s journal, it suggests she not only survived Harrington, but managed to secure ownership of property, possibly using documents Harrington had been compelled to sign before his death.

The journal’s final entry, dated March 15, 1854, contains a passage that many researchers have found particularly chilling.

I have ceased to look over my shoulder.

There is no need.

What pursued me has been laid to rest.

What remains is a life neither free nor bound, but something else entirely.

A life defined not by what was done to me, but by what I chose to do in return.

Some would call it vengeance.

I call it balance restored.

The scales that were tipped for so long have finally found their center.

I sleep without dreams now.

The home where the journal was discovered had been owned from 1854 to 1872 by a woman registered in property records as Margaret Hamilton, described in local church records as a free woman of color of means.

She was respected in the community for her philanthropy, particularly her support of education for formerly enslaved children following the Civil War.

Upon her death, her property was bequeethed to a school for freed people.

No surviving photographs of Margaret Hamilton exist, and her grave in the St.

Augustine Cemetery bears only her name and the dates, 1824 to 1872.

A life spanning from bondage to freedom, from obscurity to quiet influence.

In 1968, author James Baldwin visited the site of Raven’s Cross while researching a book that was never completed.

His notes, archived at the Shamberg Center for Research in Black Culture, include a reflection on standing among the ruins.

There is something in this place that resists conventional narratives of victimhood.

The horror here is not just what was done to the enslaved, but what one of the enslaved chose to do in return, not in a moment of desperate rebellion, but through a calculated campaign of psychological warfare that spanned years.

It forces us to confront uncomfortable questions about justice, vengeance, and the human capacity for both suffering and inflicting suffering.

The truly terrifying aspect of Raven’s Cross is not that it reveals the inhumanity of the enslaver, which history has amply documented, but that it reveals the full humanity of the enslaved, including the human capacity for methodical retribution.

In 1971, a descendant of Isaac Thornton published a family memoir that included a brief but significant detail about his ancestors connection to the Ravens Cross case.

According to family law, Thornton had first met Martha when visiting the Harrington Plantation on Business in 1844, the year before she was sold to Philadelphia.

The memoir states, “Family tradition holds that our ancestor recognized something exceptional in the young woman’s composure and intelligence following her mother’s death.

He arranged her purchase specifically because he saw in her a useful ally in his ongoing business rivalry with the Harringtons.

What he could not have anticipated was that she would ultimately orchestrate a form of justice that exceeded even his considerable capacity for calculating retribution.

The memoir also suggests that Thornton’s decision to use Martha as an instrument in forcing Harrington into a humiliating marriage was not entirely his own idea.

According to the author, family letters indicated that the plan originated with the woman herself, who suggested it with such compelling logic that Thornton came to believe it was his own inspiration.

This pattern of subtle influence that leaves the influence party believing they have maintained their autonomy mirrors precisely what later reportedly occurred between Martha and Harrington, suggesting a methodical approach to manipulation that Martha had refined over years.

In 1984, during an archaeological survey of the Ravens Cross site conducted as part of an environmental impact study for a proposed development, which was ultimately abandoned, researchers discovered a small underground chamber beneath what had been Martha’s room in the plantation house.

The chamber, approximately 6 ft square and 5 ft high, contained evidence of habitation, a small pallet, remnants of candles, and most significantly the walls were covered with writing.

Much of this writing had been rendered illeible by moisture and time, but portions remained decipherable.

Dr.

Elellanena Jenkins, the archaeologist who documented the chamber, described the writing as a methodical record of observed behaviors, weaknesses, and potential points of psychological vulnerability.

The fragmented text included observations about sleeping patterns, food preferences, superstitions, and fears.

One legible section read, “Fears silence more than noise.

fears stillness more than motion.

Fears watching more than confrontation.

Use this.

Another section contained what appeared to be a schedule or timeline with dates spanning several years, though the associated events were no longer readable.

Jenkins’s report, published in the Journal of Historical Archaeology in 1985, concluded, “The chamber appears to have been used during Martha’s initial time at the plantation before her elevation to the status of Harrington’s wife.

The evidence suggests it served as a place where she could document and plan what appears to have been an extraordinarily patient campaign of psychological manipulation.

The methodical nature of the notes, their focus on exploitable weaknesses, and the apparent timeline indicating a years’s long strategy suggest a level of calculation that transforms our understanding of this historical case from one of spontaneous role reversal to one of meticulously planned psychological warfare.

The development company that had commissioned the environmental impact study abruptly withdrew their proposal following the discovery of the chamber.

The company’s internal correspondence, which became public during a subsequent lawsuit by investors, included a memo from the CEO stating, “The historical complications associated with this property make it unsuitable for residential development.

The potential for negative publicity outweighs any projected profit margin.

The land was subsequently donated to a conservation trust with the stipulation that no construction would ever take place on the site.

In 2010, a graduate student in forensic anthropology at the University of Tennessee obtained permission to re-examine the skeletal remains discovered in the unmarked grave near Harrington’s burial site in 1959.

Using advanced analytical techniques not available during the original examination, the researcher determined that the woman had died not in 1853 but significantly later, possibly in the 1870s based on trace elements present in the bone structure.

This finding contradicts the assumption that the remains belong to Martha and suggests instead that they may have been those of another woman entirely, perhaps someone connected to the Harrington family who was buried near Elias years after his death.

This discovery reignited interest in the Margaret Hamilton of St.

Augustine, leading researchers to petition for an examination of her grave.

The request was denied by local authorities out of respect for the deceased, leaving the potential connection between Martha and Margaret Hamilton in the realm of compelling but unproven historical theory.

The most recent scholarly examination of the Ravens Cross case was published in 2018 by Dr.

Valerie Henderson, a historian specializing in power dynamics during American slavery.

Her analysis offers perhaps the most comprehensive psychological assessment of what may have transpired.

What makes the Raven’s Cross case so disturbing to modern sensibilities is not that it inverts the expected power dynamic, but that it suggests a form of resistance to oppression that operates not through physical rebellion or escape, but through psychological colonization.

Martha appears to have identified the fundamental vulnerability in the system of human bondage that those who claim ownership of others remain themselves vulnerable to influence, manipulation, and psychological dependency.

Henderson continues, “The evidence suggests that Martha did not merely seize an opportunity for revenge when it presented itself, but rather created that opportunity through years of patient calculation, strategic alliance building, and psychological study of her target.

” She weaponized the very invisibility forced upon her, the assumption that an enslaved woman, particularly one described dismissively in records as stout and unsuitable, could not possibly possess the intellectual and psychological capacity for such manipulation.

This weaponization of underestimation represents a form of resistance rarely acknowledged in our narratives of slavery and its aftermath.

The land where Raven’s Cross plantation once stood remains undeveloped to this day, protected by its conservation status.

Local residents continue to report unusual experiences in the vicinity.

Not dramatic supernatural phenomena, but subtle disquing sensations, the feeling of being watched, sudden inexplicable anxiety, or what one visitor in 2015 described as a weight of attention as though the land itself is evaluating you.

Historians, psychologists, and cultural theorists continue to debate the significance of the Raven’s Cross case.

Some view it as a powerful, if disturbing, example of resistance within an oppressive system, while others question the ethical implications of celebrating what appears to have been a campaign of psychological torture.

Regardless of the justification, what remains undisputed is the case’s power to unsettle conventional narratives about power, agency, and the human capacity for both suffering and calculated retribution.

Perhaps the most fitting epilogue to this disturbing chapter in American history comes not from academic analysis, but from the words attributed to Martha herself in the final page of the St.

Augustine journal.

They will look for me in graveyards and records, in the spaces between official histories.

They will not find me there.

I exist now in the silence between spoken words, in the hesitation before action, in the moment of doubt that precedes certainty.

I have become what was done to me, transformed and returned.

Justice is not always loud.

Sometimes it whispers.

Sometimes it merely watches and waits.

I have learned to be patient.

I have learned that the most complete victory is the one your adversary never recognizes as defeat.

when they believe themselves still in control even as the ground shifts beneath them.

There is power in being underestimated.

There is freedom in being overlooked.

There is victory in being thought defeated.

Remember this today.

The ruins of Raven’s Cross lie silent among the encroaching forest of coastal South Carolina.

The stone foundations remain visible, a testament to what once stood there and the events that transpired within those walls.

Visitors to the area, the few who know its location and history, often report an unsettling sensation, not of supernatural dread, but of being measured, evaluated, judged by something unseen yet acutely perceptive.

As one local guide described it in 2020, it ain’t ghosts people feel out there.

It’s something colder and more calculating than that.

It’s like the air itself remembers what happened.

How patience and planning can turn the tables when you least expect it.

It’s a place that reminds you to watch carefully who you think ain’t watching you.

The case of Raven’s Cross remains officially unresolved in historical records, existing in that liinal space between documented fact and psychological horror.

It stands as a stark reminder that the darkest chapters in human history contain complexities that resist simple categorization, and that the capacity for calculated retribution is as much a part of our shared humanity as the capacity for suffering and endurance.

In the silent ruins of Raven’s Cross, that complexity continues to echo through time, patient, watchful, and unresolved.

News

✈️ U.S. F-15 FIRST STRIKE — ALLEGED CARTEL DRUG LAB ERASED IN SECONDS AS SKY ERUPTS IN A BLINDING FLASH ✈️ What officials described as a precision operation turned the night into daylight, with jets screaming overhead and a suspected production site reduced to smoking rubble in moments, sending a shockwave across the region and a message that the airspace above is no safe haven for hidden empires 👇

The Last Fortress: A Shocking Revelation In the heart of the Mexican jungle, Diego stood at the entrance of the…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: FBI & ICE SHATTER ALLEGED TRUCKING NETWORK WITH SOMALI TIES — 83 ARRESTED, $85M IN CASH AND WEAPONS STACKED AS EVIDENCE 🚨 Before sunrise, federal agents swept through depots and dispatch offices, hauling out duffel bags of currency and seizing firearms while stunned neighbors watched a logistics operation authorities claim was hiding a sprawling criminal enterprise behind everyday freight routes 👇

The Shadows of the Ghost Fleet In the heart of the Midwest, where the snow fell like a blanket over…

🚨 FBI & ICE STORM GEORGIA “CARTEL HIDEOUT” — GRENADE LAUNCHER DISCOVERED AND $900K IN DRUGS SEIZED IN A DAWN RAID THAT SHOCKED THE BLOCK 🚨 What neighbors thought was just another quiet morning exploded into flashing lights and tactical vests as agents swept the property, hauling out weapons and evidence while officials described a months-long investigation that culminated in a swift, coordinated takedown 👇

The Unraveling of Shadows: A Tale of Betrayal and Redemption In the heart of Jackson County, Georgia, the air was…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: DEA & FBI CRUSH ALLEGED CARTEL TRUCKING EMPIRE — HIDDEN ROUTES MAPPED, DRIVERS DETAINED, AND MILLIONS STACKED AS EVIDENCE 🚨 Before sunrise, highways turned into a grid of flashing lights as agents intercepted rigs, cracked open trailers, and traced coded dispatch logs, revealing what officials describe as a logistics web hiding in plain sight behind ordinary freight lanes 👇

The Fall of Shadows: A Cartel’s Empire Exposed In the dimly lit corridors of power, where shadows danced with deceit,…

🚢 U.S. NAVY TRAPS SINALOA CARTEL’S ALLEGED $473 MILLION “DRUG ARMADA” AT SEA — AND THE HIGH-STAKES STANDOFF UNFOLDS UNDER FLOODLIGHTS AND ROTOR WASH 🚢 Radar screens lit up, cutters boxed in fast boats, and boarding teams moved with clockwork precision as authorities described a sweeping maritime interdiction that turned open water into a chessboard, stacking seized cargo on deck while prosecutors hinted the ripples would travel far beyond the horizon 👇

The Abyss of Deceit: A Naval Reckoning In the heart of the Caribbean, where the turquoise waters glimmered under the…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: DEA & FBI DESCEND ON MASSIVE TEXAS LOGISTICS HUB — 52 TONS OF METH SEIZED AS 20 POLITICIANS ALLEGEDLY TIED TO A SHADOW NETWORK ARE THRUST INTO THE SPOTLIGHT 🚨 What began as a quiet federal probe detonated into a sweeping raid of warehouses and boardrooms, with agents hauling out towering stacks of evidence while stunned insiders whisper that the real shockwave isn’t just the drugs — it’s the powerful names now facing intense scrutiny 👇

Shadows of the Underground: The Texas Cartel Unveiled In the heart of Texas, where the sun sets over sprawling landscapes,…

End of content

No more pages to load