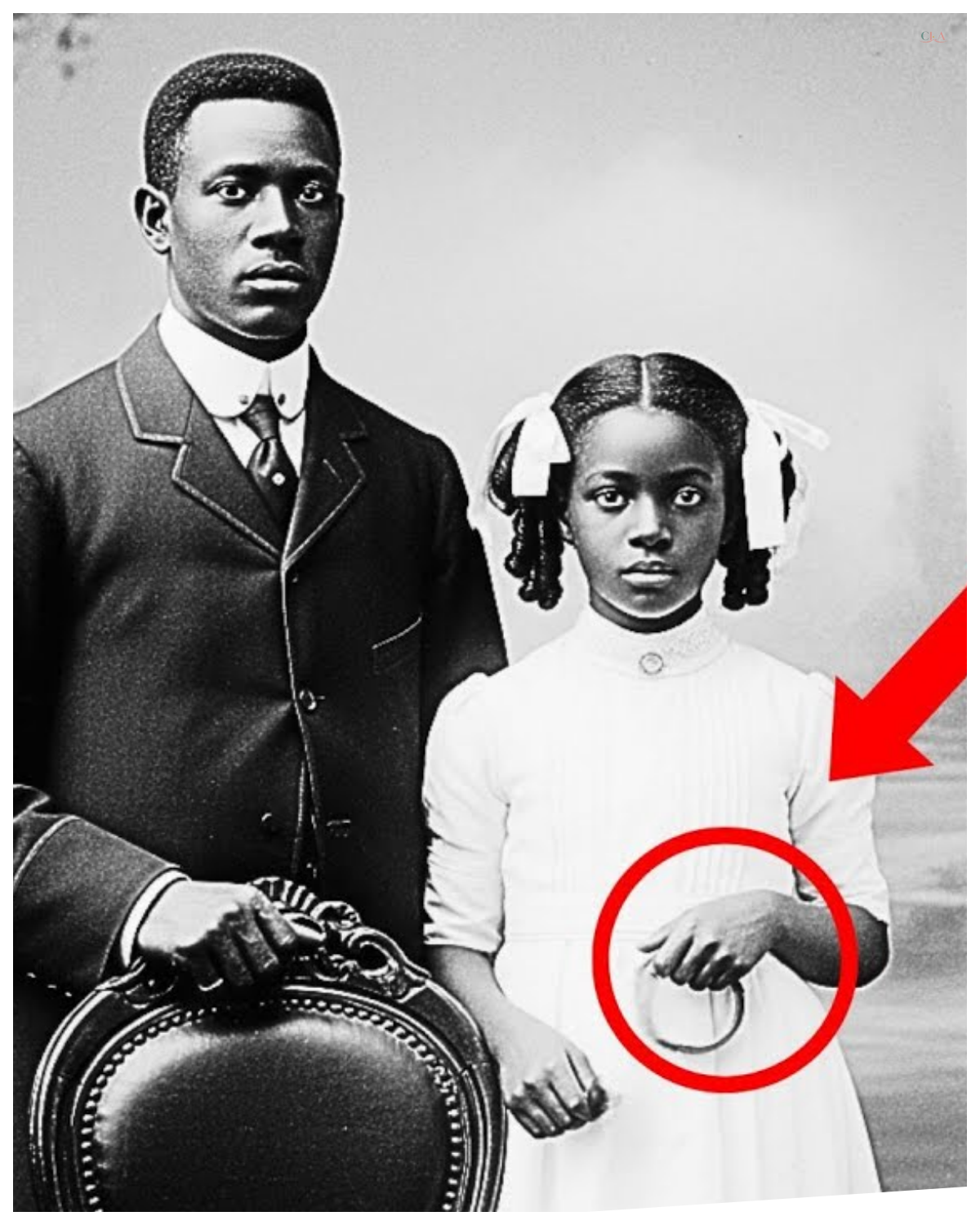

Experts thought this 1910 studio photo was peaceful until they saw what the girl was holding.

Dr.Maya Johnson’s hands trembled slightly as she held the photograph under the afternoon light streaming through her office window at Emory University in Atlanta.

The image had cost her $300 at a weekend estate sale in Decar, but something about it had called to her the moment she saw it among dusty boxes of forgotten memories.

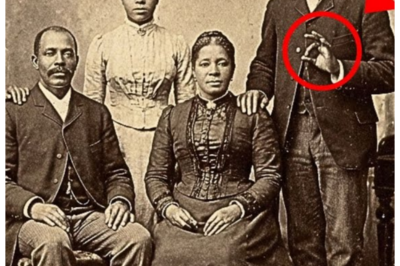

The photograph showed a black family of three, formerly posed in what appeared to be a professional studio setting from 1910.

The father stood tall and dignified in a dark suit, one hand resting on the back of an ornate chair.

The mother sat gracefully, her posture perfect, wearing a high collared white blouse with delicate lace trim.

Between them stood a young girl, perhaps 8 years old, in a pristine white dress with ribbons in her carefully styled hair.

Maya had seen hundreds of photographs from this era during her 15 years researching African-American history in the post-reonstruction South.

Most such images were stiff, formal affairs where black families presented themselves with fierce dignity to counter the degrading stereotypes of the time.

This photo seemed no different at first glance, but Maya couldn’t shake the feeling that something was off.

The family’s expressions held an unusual intensity.

Not quite smiling, not quite solemn, but something else entirely.

The girl’s eyes seemed to look directly through the camera through time itself, as if trying to communicate something urgent across the decades.

Setting the photo on her desk, Mia pulled out her digital magnification equipment, a tool she’d used countless times to examine historical documents and images.

As she adjusted the lens and brought different sections of the photograph into sharp focus, she studied each detail methodically.

The studio’s painted backdrop depicting a serene garden scene, the quality of the family’s clothing, the photographers’s signature barely visible in the corner.

Then she focused on the girl’s hands folded dearly in front of her white dress.

Maya’s breath caught.

There, partially obscured by the careful positioning and the grain of the old photograph, was something she hadn’t noticed before.

The girl’s right hand clutched a small metal object, no more than 2 in long.

Maya increased the magnification, her heart racing.

The object became clearer, curved metal, broken at one end, with what appeared to be a hinge mechanism still visible.

Her professional training told her exactly what she was looking at, but her mind resisted the implications.

It was a shackle.

A child-sized shackle broken clean through the middle.

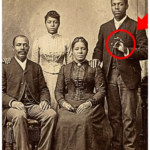

The peaceful studio portrait suddenly transformed before her eyes.

This wasn’t just another formal family photo documenting dignity and respectability.

This was something far more significant.

A deliberate, dangerous act of testimony hidden in plain sight for over a century.

Maya spent the next three days barely sleeping.

Consumed by the photograph, she canceled two lecture classes and ignored emails piling up in her inbox.

instead converting her office into a makeshift research center.

The walls became covered with printouts, notes, and timeline charts as she began piecing together the context of this mysterious image.

The photographers’s mark in the corner read Sterling and Associates, Memphis, Tennessee, 1910.

Maya searched through digital archives of Memphis business directories from that era and found that Sterling and Associates had operated a portrait studio on Beiel Street from 1908 to 1915, catering to both white and black clientele.

unusual for the time, which suggested the photographer might have been more progressive than most.

She reached out to colleagues across the country, sending highresolution scans of the photograph to experts in early 20th century photography, material culture, and African-American history.

Within 48 hours, her instincts were confirmed.

Dr.

Robert Chen at Howard University, a specialist in historical restraint devices, examined the magnified image and sent back a sobering email.

Maya, what you found is consistent with juvenile restraints used in the convict leasing system and apprenticeship programs that proliferated across the south after reconstruction.

These were particularly common in agricultural and domestic labor arrangements where children were bound to employers under legal pretexts.

The break pattern suggests forcible removal rather than unlocking.

Where did you find this? Maya stared at his words, feeling the weight of history pressing down on her shoulders.

She had studied the convict leasing system extensively.

That brutal practice where southern states leased prisoners, overwhelmingly black men arrested on trumped up charges to private companies for labor.

But the apprenticeship system that trapped children was less documented, more hidden in the shadows of historical record.

She pulled out her well-worn copy of Slavery by Another Name by Douglas Blackman and flipped to the chapters on child labor.

The system had been simple and devastating.

After the abolition of slavery, southern legislators passed apprenticeship laws allowing courts to bind black children to white employers if their parents were deemed unable to support them.

A judgment applied arbitrarily and maliciously.

These children, some as young as five, were essentially enslaved under legal cover, forced to work without pay until adulthood.

Maya returned to the photograph with fresh eyes, examining the family’s clothing more carefully.

The quality was too fine for people emerging directly from poverty.

The father’s suit showed expert tailoring.

The mother’s blouse featured expensive lace, and the girl’s white dress was immaculate.

This suggested the family had achieved some measure of prosperity or had saved significantly for this formal portrait.

Why would they risk including such a provocative object in an official photograph? In 1910, Memphis, openly displaying evidence of forced labor or criticizing the social order, could bring deadly consequences.

Black families lived under constant threat of violence, false accusations, and reinslavement through the criminal justice system.

Maya knew she needed to understand Memphis in 1910 to make sense of the photograph.

She spent the following week immersed in historical records, painting a picture of the city and the dangers this family would have faced.

Memphis in 1910 was a city of contradictions.

Beiel Street thrived as a center of black culture, commerce, and music where entrepreneurs built businesses and created vibrant community spaces.

Yet, this prosperity existed within a larger system designed to suppress and exploit.

Tennessee had implemented Jim Crow laws with brutal efficiency, and the economic gains black families managed to achieve were constantly under threat.

The city’s African-American population had grown significantly since the Civil War, but so had the mechanisms of control.

Vagrancy laws allowed police to arrest black men for being unemployed, then leased them to farms and factories.

Debt pen trapped families in cycles of forced labor through manipulated contracts and inflated commissary charges.

and the apprenticeship system quietly siphoned children away from their families under the guise of education and vocational training.

Maya discovered a 1909 report by a northern journalist who had investigated labor conditions in the Memphis area.

His account described farms in the surrounding counties where black children worked alongside adults in conditions indistinguishable from slavery.

The children had been apprenticed by county judges, often without their parents’ knowledge or consent, sometimes taken directly from families, accused of minor infractions, or simply deemed too poor.

One passage made Mia’s blood run cold.

The children wore metal cuffs at night to prevent escape.

During the day, these restraints were removed for work, but kept nearby as a constant threat.

Several children showed scars on their wrists and ankles from prolonged wearing of these devices.

She cross- referenced this with court records from Shelby County, where Memphis was located.

Between 1900 and 1915, over 300 black children had been legally apprenticed.

Their fates documented in dry legal language that barely concealed the human suffering involved.

Many records listed only first names and ages, making it nearly impossible to trace what happened to these children or whether they were ever reunited with their families.

Maya began searching for any families who might have escaped the system around 1910, who might have had the resources and courage to commission a formal photograph.

She needed names, locations, anything that could connect to the image on her desk.

In the Tennessee State Archives digital collection, she found Beiel Street business advertisements from 1910.

One caught her attention.

Sterling and Associates, portraits of distinction for families of character.

Discretion assured.

That last phrase was unusual.

Why would a photographer advertise discretion? Maya contacted the Memphis Public Libraryies history department, and a librarian named James Porter responded enthusiastically.

He explained that Sterling and Associates had a reputation among the black community for being sympathetic and trustworthy, willing to document aspects of life that other photographers wouldn’t touch.

They photographed families just after funerals when other studios refused,” James wrote.

“They documented blackowned businesses before they were burned down.

If someone wanted a photograph that told a truth others wanted hidden, Sterling was where you went.

” Two weeks into her investigation, Maya finally caught her first real break.

She had been combing through Memphis city directories, church records, and census data, looking for black families in the Beiel Street area around 1910 who might have had a daughter approximately 8 years old.

The 1910 census listed thousands of black residents in Memphis, but most entries were frustratingly sparse.

Then she found something promising in the records of Second Congregational Church, a historically black congregation that had been active in the community since reconstruction.

Among the membership roles from 1910, one entry included a notation in the margin.

Family rejoined July 1910 after return from Fet County.

The entry listed Samuel Price, age 34, laborer.

Clara Price, age 29, laress, and Ruth Price, age 8.

The notation about returning from Fet County was unusual enough to warrant attention.

Why would a church secretary note where a family had been? Mia’s hands shook as she searched for Fyet County records.

Located about 50 mi east of Memphis, Fyet County was predominantly agricultural with a complicated racial history.

After reconstruction, it had become notorious for exploitative labor practices targeting the black population.

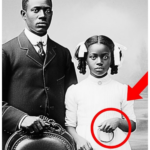

In a collection of county court records from 1905, Maya found what she had been dreading, order of apprenticeship.

Ruth Price, female child of color, aged three years, to be apprenticed to the household of Mr.

William Dawson, farmer, for purpose of learning domestic skills and receiving Christian instruction until age 18.

Parents Samuel Price and Clara Price determined to be unable to provide adequate support.

Maya read the document three times, feeling sick.

Ruth had been three years old when she was taken from her parents.

The legal language was sterile, but Maya could imagine the scene.

A little girl torn from her mother’s arms, a father powerless to stop it, the weight of a system designed to break families apart.

She searched for more information about William Dawson and found census records listing him as a farmer with 200 acres and several apprenticed laborers, a euphemism that barely disguised the reality.

There were no records of him ever being charged with mistreatment, but that meant little in a system where the suffering of black children carried no legal weight.

But Ruth had somehow returned to her family.

She had escaped.

And in July 1910, just weeks after the family’s return to Memphis, they had walked into Sterling and Associates’s studio and commissioned a portrait that would serve as permanent evidence of what Ruth had endured.

Maya needed to know how they had gotten her back and why they had risked documenting it so boldly.

She reached out to descendants of Second Congregational Church members, historians specializing in Tennessee labor history, and genealogologists who might help trace the Price family forward through time.

The breakthrough came from an unexpected source, Dr.

Patricia Lawson, a retired history professor in Memphis who specialized in black women’s activism during the Jim Crow era, responded to Maya’s inquiry with an intriguing email.

I remember hearing stories about a group of black women in Memphis who worked quietly to retrieve children from illegal apprenticeships.

They had no formal organization, no official standing, but they were effective.

Check the papers of Ida Wells.

Maya knew of Ida B.

Wells Barnett, the fearless journalist and activist who had documented lynching and fought tirelessly against racial injustice.

Wells had lived in Memphis before being driven out by death threats in 1892, but she had maintained connections to the city and visited occasionally.

In the archived correspondence at the University of Chicago, Maya found a letter Wells had written to a colleague in 1910 mentioning her work with women in Memphis who are liberating children from bondage disguised as apprenticeship.

The letter was vague on specifics.

Wells was careful knowing her mail might be intercepted, but it confirmed the existence of this underground network.

Maya returned to church records.

This time looking for women’s auxiliary groups, missionary societies, and charitable organizations in the minutes from second congregational churches, women’s mission society from 1909.

She found an entry committee to visit afflicted families.

Clara Price to be assisted in her distress regarding her daughter’s unlawful detention.

The pieces began falling into place.

Clara Price had reached out to the church women who had experienced navigating the treacherous landscape of Jim Crow justice.

These women understood the systems vulnerabilities and knew how to exploit them.

Maya found court records from March 1910 showing that Samuel Price had filed a petition in Shelby County court requesting the return of his daughter from apprenticeship in Faget County.

The petition claimed he had secured steady employment with the Memphis Street Railway Company and that his wife operated a successful laundry business from their home, proving they could support their child.

Normally, such petitions from black parents were ignored or denied.

But this one had something unusual.

It was accompanied by an affidavit from a white attorney named Henry Thompson, testifying to the Price family’s good character and financial stability.

Thompson’s name appeared in other records as someone who occasionally took cases defending black Memphians, a rarity that would have made him controversial in white society.

The court granted the petition in May 1910, ordering Ruth’s return to her parents, but Mia knew the legal victory was only part of the story.

Someone had to physically retrieve Ruth from Dawson’s farm, and Mia doubted he had released her willingly.

In a small FET County newspaper from June 1910, she found a brief article.

Disturbance at Dawson Farm, county sheriff called to restore order after Memphis party arrived, claiming custody of negro child apprentice.

Matter settled according to court order.

No charges filed.

That sparse report concealed what must have been a terrifying confrontation.

Maya imagined Clara Price, perhaps accompanied by church women and attorney Thompson, arriving at Dawson’s farm with the court order demanding her daughter back.

The presence of White attorney Thompson might have been the only thing preventing violence.

Maya needed to understand the significance of the broken shackle in the photograph.

Why had Ruth held it during the portrait? What message was the family trying to send? She consulted with Doctor Angela Foster, a colleague who specialized in African-American visual culture and resistance during the Jim Crow era.

Angela traveled to Atlanta to examine the photograph in person, bringing sophisticated imaging equipment that could analyze details invisible to the naked eye.

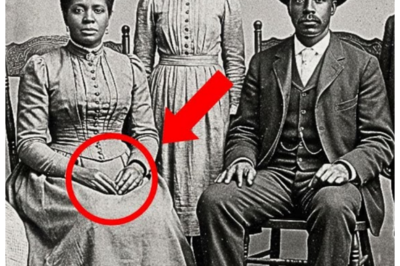

This is extraordinary,” Angela said as she studied the magnified image on her laptop screen.

“Look at how deliberately Ruth is holding the shackle.

Her fingers are positioned to display it clearly, even though it’s small enough that casual observers might miss it.

This wasn’t accidental.

This was intentional testimony.

” They examined other elements of the photograph with fresh attention.

The father’s hand on the chair back wasn’t merely a conventional pose.

His fingers were tense, gripping the wood firmly.

The mother’s expression, which Maya had initially read as dignified composure, showed traces of defiance in the set of her jaw and the direct challenge in her eyes.

They knew exactly what they were doing, Angela continued.

In 1910, there was no guarantee this photograph would ever be widely seen, but they made it anyway.

They were documenting the truth for the future.

Maybe for Ruth herself when she was older, maybe for history.

This was their act of resistance, refusing to let what happened to their daughter be forgotten or erased.

Angela pointed to the broken end of the shackle.

See how clean the brake is? That wasn’t wear and tear or rust.

Someone cut through that metal deliberately, probably with a hacksaw.

That would have taken time and effort.

I think Ruth or someone who helped her kept this piece as evidence and as a symbol.

May I felt tears welling up.

The courage it must have taken for Clara and Samuel Price to commission this photograph, knowing it could bring danger to their family if the wrong people saw it was almost incomprehensible.

In 1910, Memphis, openly displaying evidence of resistance to white authority, could result in arrest, violence, or death.

Yet, they had done it anyway.

They had dressed in their finest clothes, taken their daughter to the most respectable studio they could find, and posed for a portrait that would permanently document both their dignity and their defiance.

The broken shackle was Ruth’s proof that she had survived, that they had won her back, that the system had not defeated them.

Maya and Angela spent hours discussing the photograph’s historical significance.

Images like this were incredibly rare.

Most documentation of child apprenticeship systems came from white observers or official records that minimized the brutality involved.

To have evidence from the perspective of a family that had lived through it and escaped was nearly unprecedented.

You need to find out what happened to Ruth after this photograph was taken.

Angela said, “Did she survive? Did she get to live a full life? The story doesn’t end here.

” Tracing Ruth Price’s life after 1910 proved challenging but not impossible.

Maya started with census records, following the family through the decades.

The 1920 census showed Samuel, Clara, and Ruth still living in Memphis, with Samuel working as a railway porter and Clara continuing her laundry business.

Ruth was listed as 18 years old and employed as a teacher at a colored school.

The fact that Ruth had become a teacher was significant.

For a black girl in the South who had spent years in forced labor to achieve enough education to teach meant extraordinary determination and support from her family.

Maya wondered if Ruth had been motivated by her own experience, wanting to ensure other children received the education she had been denied during her apprenticeship.

Maya contacted the Memphis Board of Education archives and found teacher employment records.

Ruth Price had taught at Le Moy Elementary School, a school for black children founded by the American Missionary Association.

Her employment file included a brief handwritten application from 1918, stating she had completed normal school training and had experience working with young children.

There was something else in the file, a letter of recommendation from attorney Henry Thompson, the same lawyer who had helped retrieve Ruth from her apprenticeship eight years earlier.

He wrote, “Miss Ruth Price demonstrates exceptional character and dedication to education.

Despite significant hardships in her early life, she has pursued learning with admirable persistence.

She will be an asset to any institution fortunate enough to employ her.

” Maya felt a connection forming across time.

These weren’t just names and records anymore.

These were real people who had fought, survived, and built meaningful lives despite systematic attempts to destroy them.

The 1930 census showed Clara Price, now widowed, living with Ruth, who was listed as married to Thomas Williams, a postal worker.

Samuel had passed away in 1927, according to death records at Elmwood Cemetery.

Maya visited the cemetery on a cold February morning, walking among weathered headstones, until she found Samuel Price’s marker, a simple granite stone with his name, dates, and the inscription, “Beloved Father and husband.

She stood there for a long time, thinking about the man in the photograph who had fought to bring his daughter home.

Samuel had lived 17 more years after that portrait, long enough to see Ruth grow into adulthood, marry, and build her own life.

That was a victory, even if it was one the history books had never recorded.

Maya continued following Ruth’s trail through marriage records, city directories, and newspaper mentions.

Ruth Williams had taught for 32 years, retiring in 1950.

She appeared in several articles about negro education in Memphis, always described as a dedicated and respected teacher.

In a 1945 Memphis newspaper article about educational advances in the black community, Ruth was quoted, “Education is freedom.

Every child deserves the chance to learn and grow without interference or exploitation.

” The students Maya’s research took an unexpected turn when she posted about her findings on a genealogy forum focused on Memphis families.

Within three days, she received an email from a woman named Linda Harris in Nashville who had been researching her own family history.

I believe Ruth Price Williams was my great-grandmother.

Linda wrote, “My grandmother, Dorothy Williams, was Ruth’s daughter.

I have some of Ruth’s belongings, including a box of old photographs and papers.

If you’re researching the same Ruth Price, I’d be happy to meet with you.

” Maya drove to Nashville the following Saturday, her heart pounding with anticipation.

Linda, a woman in her 60s with kind eyes and Ruth’s same determined expression, welcomed her into a comfortable home filled with family photos spanning generations.

“I never knew my great-grandmother personally,” Linda explained as they sat in her living room.

“She passed away in 1969 before I was born, but my grandmother, Dorothy, told me stories about her, about how strong she was, how she valued education above everything.

” Linda brought out a worn cardboard box.

Inside were treasures, report cards from Ruth’s teaching career, a Bible with family names inscribed on the fly leaf, letters, and several photographs.

One photograph showed an elderly Ruth in the 1960s standing in front of a classroom, her expression proud and gentle.

Grandmother Dorothy said Ruth never talked much about her childhood, Linda continued.

She would get quiet if anyone asked about it.

But once when Dorothy was a teenager, Ruth told her something that stayed with her.

She said, “I was taken from my parents when I was very young, and I worked on a farm where children weren’t treated kindly.

But my mother never stopped looking for me, and when I came home, I promised myself I would help other children have better lives.

” Mia felt chills.

Linda didn’t know about the photograph Mia had found, or the broken shackle.

This oral history passed down through generations, confirmed what Mia had discovered.

At the bottom of the box, wrapped carefully in tissue paper, Mia found something that made her gasp.

It was a small metal object curved and broken with a hinge still visible.

The other half of the shackle from the photograph.

Do you know what this is? Maya asked, her voice barely above a whisper.

Linda shook her head.

It was in Ruth’s things after she died.

My grandmother kept it, but never knew what it was.

She thought maybe it was part of an old farm tool or something Ruth had kept from childhood.

Maya explained her research, showing Linda the photograph on her laptop, zooming in on Ruth’s hand in the piece of broken shackle.

As understanding dawned on Linda’s face, tears began flowing down both women’s cheeks.

She kept it her whole life, Linda whispered.

60 years.

Why? As a reminder, Mia said, of what she survived, of what her parents fought to save her from.

Maybe also as evidence in case anyone ever questioned her story.

Maya knew the story needed to be shared.

With Linda’s permission and collaboration, she began planning an exhibit at Emory University’s African-American History Center.

The exhibit would feature the 1910 photograph alongside the historical context, documents from Mia’s research, and artifacts from Ruth’s life, including both pieces of the shackle, now reunited after more than a century.

The process took 6 months.

Maya worked with curators, conservation specialists, and designers, to create an exhibit that would honor the Price family’s courage while educating visitors about the broader system of child exploitation that had entrapped thousands of black children in the postreonstruction south.

Linda became an invaluable partner, contributing family stories, photographs, and context that enriched the narrative.

Together, they reached out to other descendants of Second Congregational Church members, many of whom shared stories about the network of women who had worked to liberate apprenticed children.

Some families had their own stories of children taken, and in heartbreaking cases, never returned.

Maya also connected with historians researching similar systems in other southern states.

The apprenticeship system that had trapped Ruth existed across the South from Virginia to Texas.

Yet, it remained one of the least studied aspects of Jim Crow oppression.

Many scholars were grateful for the documentation Maya had compiled, recognizing its value for future research.

In September, the exhibit opened with a ceremony attended by more than 200 people, including Linda and several dozen other descendants of Memphis families affected by the apprenticeship system.

Local news coverage brought even more attention, and within weeks, the story spread nationally.

Maya stood before the mounted photograph of the Price family, addressing the crowd.

When we look at historical photographs, we often see only surfaces, the clothes people wore, the studios where they posed, the formal expressions they adopted for the camera.

But this photograph is different.

It demands that we look closer, that we see the broken shackle in Ruth’s hand, and understand what it represents.

It tells us that resistance took many forms.

That families fought back against injustice in whatever ways they could.

And that the truth has a way of surviving, even when systems of power tried to bury it.

Linda spoke next, her voice steady but emotional.

My great-g grandandmother Ruth lived to be 73 years old.

She taught hundreds of children, loved her family, and built a life of dignity and purpose.

The system tried to steal her childhood, but it didn’t succeed in stealing her future.

She wanted us to remember that.

That’s why she kept the shackle.

That’s why her parents risked everything for that photograph.

They knew someday someone would understand.

Six months after the exhibit opened, Maya published her research in the Journal of Southern History, contributing to a growing body of scholarship examining postreonstruction child labor exploitation.

The article sparked renewed interest in documenting these overlooked histories, and several universities launched projects to uncover similar stories in their regions.

Linda established scholarship in Ruth’s name at Le Moy Owen College, the institution that had grown from the school where Ruth had taught.

The scholarship supported students pursuing education degrees, particularly those who had overcome significant hardships.

At the first scholarship ceremony, Linda displayed the 1910 photograph prominently along with a quote from Ruth.

Education is freedom.

Maya continued her research, discovering records of 13 other children who had been apprenticed in Fet County between 1900 and 1915 and later retrieved by their families with help from the Memphis Women’s Network.

Each story represented an act of courage and resistance that had gone undocumented until now.

She began compiling these stories into a book determined to give voice to families whose struggles had been erased from official histories.

The photograph itself, now on permanent display at the National Museum of African-American History and Culture in Washington, became a touchstone for discussions about hidden histories and visual resistance.

School groups visiting the museum often spent time in front of it.

Teachers explaining how people found ways to tell truth to power, even in the most dangerous circumstances.

Maya returned to her office at Emory on a warm spring afternoon.

Nearly a year after she had first purchased the photograph at that estate sale indicator, the walls of her office, once covered with research notes and timeline charts, had been cleared, but the impact of the work remained.

She had requests for speaking engagements across the country, invitations to collaborate on similar projects, and messages from people who had their own family stories to share.

She pulled out the original photograph, now carefully preserved in archival materials, and studied it once more.

Ruth’s eyes still seemed to look directly through time, but now Maya understood what she was communicating.

Not just the story of one child’s suffering and survival, but a larger truth about resilience, family love, and the lengths people will go to protect their children and preserve their dignity.

Samuel and Clara Price had made sure their daughter’s story would survive.

They had documented it in the most permanent way available to them, a formal photograph that would outlast memory, rumors, and the inevitable erosion of oral history.

The broken shackle in Ruth’s hand was their testimony, their evidence, their refusal to let injustice remain invisible.

As Maya turned off the lights in her office that evening, she thought about all the other photographs sitting in atticss, estate sales, and forgotten boxes, images that might hold similar secrets, waiting for someone to look closely enough to see what was hidden in plain sight.

History wasn’t just in archives and official records.

It was in the details, the small objects people carried, the messages they encoded in portraits, the stories they preserved for future generations who might finally be ready to listen.

Ruth Price had survived.

She had taught, loved, and built a legacy that extended far beyond her own lifetime.

And now, more than a century later, her story was finally being heard.

News

This Portrait from 1895 Holds a Secret Historians Could Never Explain — Until Now It’s Finally Been Exposed in Stunning Detail 🖼️ — For more than a century it hung quietly in dusty archives, dismissed as another stiff Victorian pose, until a routine scan revealed a tiny, impossible detail that made experts freeze mid-sentence, because suddenly the calm expressions looked staged, the shadows suspicious, and the entire image felt less like art… and more like evidence 👇

The fluorescent lights of Carter and Sons estate auctions in Richmond, Virginia, cast harsh shadows across tables piled with forgotten…

It Was Just a Studio Photo — Until Experts Zoomed In and Saw What the Parents Were Hiding in Their Hands, and the Room Went Dead Silent 📸 — At first it looked like another stiff, sepia family portrait, the kind you pass without a second thought, but when historians enhanced the image and spotted the tiny, deliberate objects clutched tight against their palms, the smiles suddenly felt forced, the pose suspicious, and the entire photograph transformed from wholesome keepsake into something deeply unsettling 👇

The auction house in Boston smelled of old paper and varnished wood. Dr.Elizabeth Morgan had spent the better part of…

This Forgotten 1912 Portrait Reveals a Truth That Changes Everything We Thought We Knew — and Historians Are Panicking Over What’s Hidden in Plain Sight 🖼️ — It hung unnoticed for over a century, dismissed as polite nostalgia, until one sharp-eyed researcher zoomed in and felt their stomach drop, because the face, the object, the posture all scream a secret no one was supposed to catch, turning a dusty archive into a ticking historical bombshell 👇

This forgotten 1912 portrait reveals a truth that changes everything we knew until now. Dr.Marcus Webb had been working as…

Four Years After The Grand Canyon Trip, One Friend Returned Hiding A Dark Secret

On August 23rd, 2016, 18-year-olds Noah Cooper and Ethan Wilson disappeared without a trace in the Grand Canyon. For four…

California Governor STUNNED as Amazon Slams the Brakes on Massive Expansion — Billions Vanish Overnight and a Golden-Era Promise Turns to Dust 📦 — What was supposed to be a ribbon-cutting victory lap morphs into a political nightmare as Amazon quietly freezes its grand plans, leaving empty lots, stalled cranes, and thousands of “future jobs” evaporating like smoke, while the governor stands blindsided, aides scrambling, and critics whispering that the tech titan just played the state like a pawn 👇

The Collapse of Ambition: A California Nightmare In the heart of California, where dreams are woven into the fabric of…

California Governor FURIOUS as Walmart Slashes Hundreds of Jobs Overnight — Retail Giant’s Brutal Cuts Ignite Political War and Leave Families Reeling 🛒 — One minute paychecks felt safe, the next badges stopped working and managers spoke in rehearsed whispers, as Walmart’s cold-blooded decision detonated across the state like a corporate bombshell, and the governor stormed to the podium red-faced and shaking, promising consequences while stunned workers carried boxes to their cars under gray skies 👇

The Reckoning of California: A Retail Giant’s Fall In the heart of California, the sun dipped below the horizon, casting…

End of content

No more pages to load